Selection of a Gentamicin-Resistant Variant Following Polyhexamethylene Biguanide (PHMB) Exposure in Escherichia coli Biofilms

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Colony Morphotype Identification Following PHMB Exposure of Ec04 biofilms

2.2. PHMB and Antibiotic Minimal Inhibitory Concentrations (MIC) Determination for Ec04 Derivatives

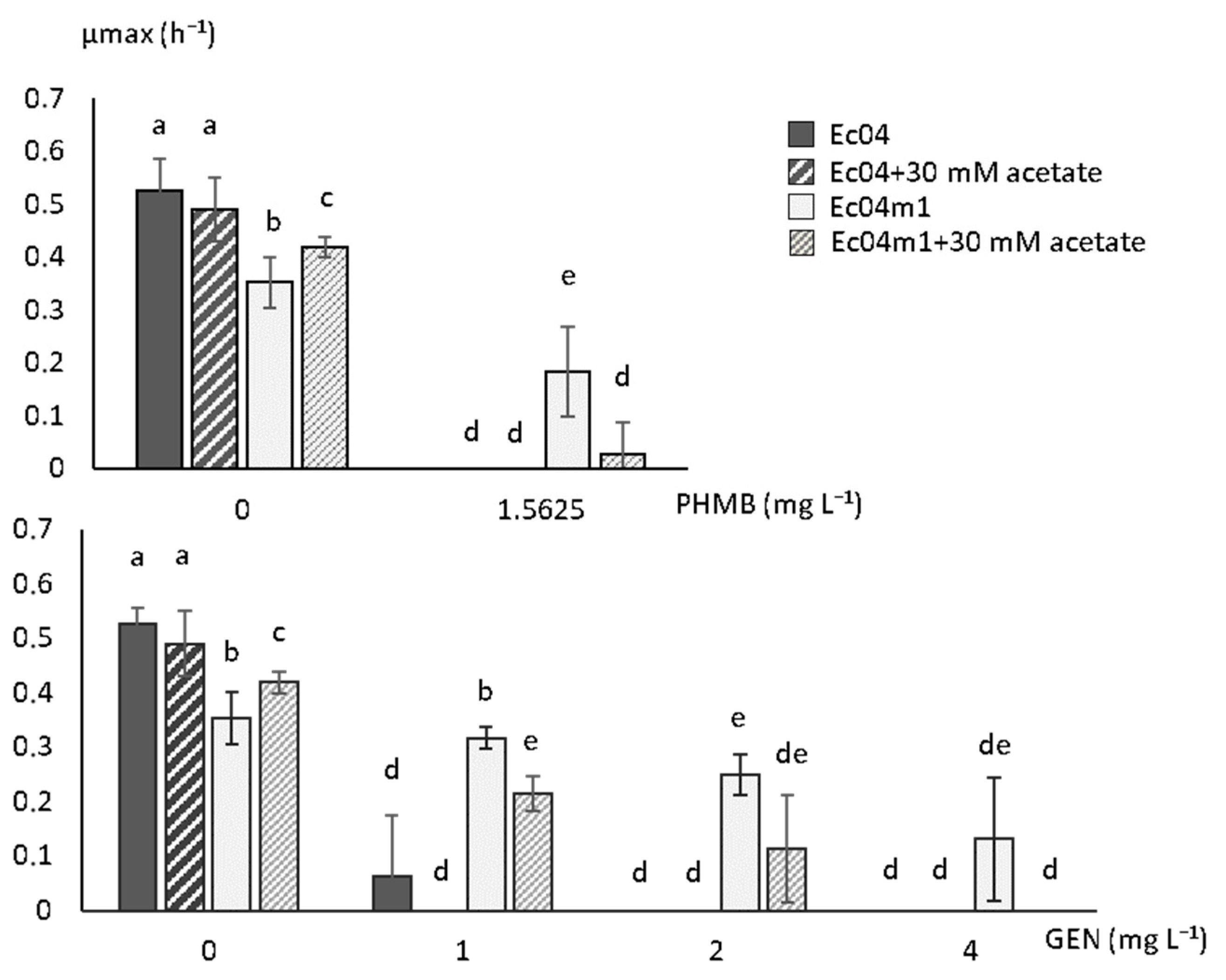

2.3. Growth Rate Parameters in Presence of PHMB and GEN

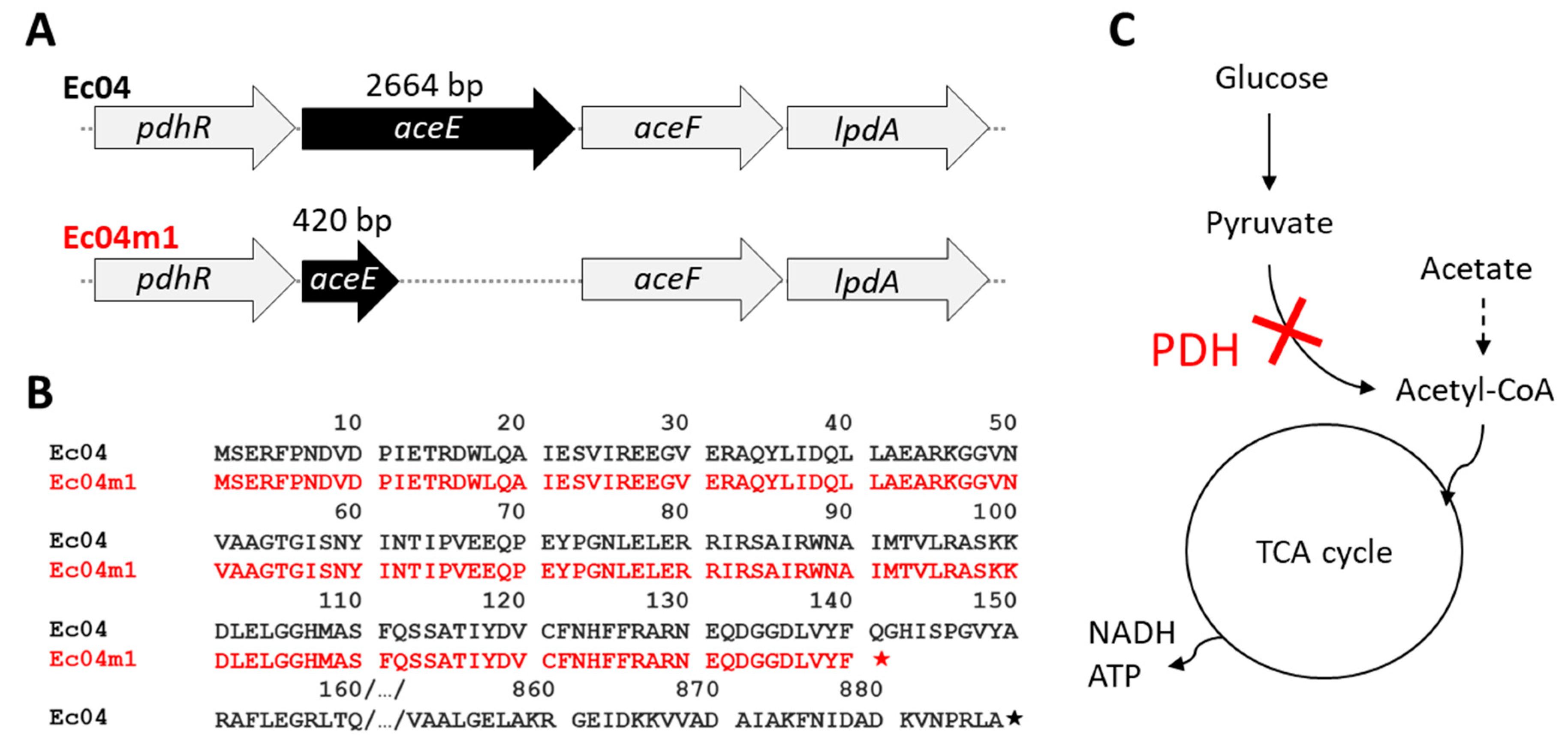

2.4. Genomic Characterization of Ec04m1 Variant

2.5. Effect of Acetate on Growth Rate in the Presence of GEN and PHMB

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strain and Growth Conditions

4.2. Biocide Susceptibility Testing

4.3. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

4.4. Adaptation Experiments to PHMB and Identification of Colony Morphology Variants

4.5. Growth Parameter Measurements

4.6. WGS and Mutation Detection

4.7. Sequence Accession Numbers

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vikesland, P.; Garner, E.; Gupta, S.; Kang, S.; Maile-Moskowitz, A.; Zhu, N. Differential Drivers of Antimicrobial Resistance across the World. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 916–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, B.M.C.; Bennett, M.; Waller, K.; Dodd, C.; Murray, A.; Gomes, R.L.; Humphreys, B.; Hobman, J.L.; Jones, M.A.; Whitlock, S.E.; et al. Anthropogenic Environmental Drivers of Antimicrobial Resistance in Wildlife. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 649, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guérin, A.; Bridier, A.; Le Grandois, P.; Sévellec, Y.; Palma, F.; Félix, B.; Roussel, S.; Soumet, C.; Listadapt Study Group. Exposure to Quaternary Ammonium Compounds Selects Resistance to Ciprofloxacin in Listeria monocytogenes. Pathogens 2021, 10, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampf, G. Biocidal Agents Used for Disinfection Can Enhance Antibiotic Resistance in Gram-Negative Species. Antibiotics 2018, 7, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Westfall, C.; Flores-Mireles, A.L.; Robinson, J.I.; Lynch, A.J.L.; Hultgren, S.; Henderson, J.P.; Levin, P.A. The Widely Used Antimicrobial Triclosan Induces High Levels of Antibiotic Tolerance In Vitro and Reduces Antibiotic Efficacy up to 100-Fold In Vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wales, A.D.; Davies, R.H. Co-Selection of Resistance to Antibiotics, Biocides and Heavy Metals, and Its Relevance to Foodborne Pathogens. Antibiotics 2015, 4, 567–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amsalu, A.; Sapula, S.A.; De Barros Lopes, M.; Hart, B.J.; Nguyen, A.H.; Drigo, B.; Turnidge, J.; Leong, L.E.; Venter, H. Efflux Pump-Driven Antibiotic and Biocide Cross-Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolated from Different Ecological Niches: A Case Study in the Development of Multidrug Resistance in Environmental Hotspots. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buffet-Bataillon, S.; Tattevin, P.; Maillard, J.-Y.; Bonnaure-Mallet, M.; Jolivet-Gougeon, A. Efflux Pump Induction by Quaternary Ammonium Compounds and Fluoroquinolone Resistance in Bacteria. Future Microbiol. 2016, 11, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, P.A.; Lemos, M.; Mergulhão, F.; Melo, L.; Simões, M. The Influence of Interfering Substances on the Antimicrobial Activity of Selected Quaternary Ammonium Compounds. Int. J. Food Sci. 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lambert, R.J.; Johnston, M.D. The Effect of Interfering Substances on the Disinfection Process: A Mathematical Model. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2001, 91, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bridier, A.; Sanchez-Vizuete, P.; Guilbaud, M.; Piard, J.-C.; Naïtali, M.; Briandet, R. Biofilm-Associated Persistence of Food-Borne Pathogens. Food Microbiol. 2015, 45, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridier, A.; Briandet, R.; Thomas, V.; Dubois-Brissonnet, F. Resistance of Bacterial Biofilms to Disinfectants: A Review. Biofouling 2011, 27, 1017–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridier, A.; Dubois-Brissonnet, F.; Greub, G.; Thomas, V.; Briandet, R. Dynamics of the Action of Biocides in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 2648–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chindera, K.; Mahato, M.; Sharma, A.K.; Horsley, H.; Kloc-Muniak, K.; Kamaruzzaman, N.F.; Kumar, S.; McFarlane, A.; Stach, J.; Bentin, T.; et al. The Antimicrobial Polymer PHMB Enters Cells and Selectively Condenses Bacterial Chromosomes. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsztein, C.; de Lucena, R.M.; de Morais, M.A. The Resistance of the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae to the Biocide Polyhexamethylene Biguanide: Involvement of Cell Wall Integrity Pathway and Emerging Role for YAP1. BMC Mol. Biol. 2011, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- ECHA French Assessment Report for the Evaluation of Active Substances in the Frame of Regulation (EU) No 528/2012 Concerning the Making Available on the Market and Use of Biocidal Products. Polyhexamethylene Biguanide PT02. 2017. Available online: https://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/8e7a0fe2-6b23-1705-d797-85c34e6f205b (accessed on 31 December 2020).

- Wand, M.E.; Bock, L.J.; Bonney, L.C.; Sutton, J.M. Mechanisms of Increased Resistance to Chlorhexidine and Cross-Resistance to Colistin Following Exposure of Klebsiella pneumoniae Clinical Isolates to Chlorhexidine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kampf, G. Acquired Resistance to Chlorhexidine-Is It Time to Establish an “antiseptic Stewardship” Initiative? J. Hosp. Infect. 2016, 94, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henly, E.L.; Dowling, J.A.R.; Maingay, J.B.; Lacey, M.M.; Smith, T.J.; Forbes, S. Biocide Exposure Induces Changes in Susceptibility, Pathogenicity, and Biofilm Formation in Uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gilbert, P.; Allison, D.G.; McBain, A.J. Biofilms in Vitro and in Vivo: Do Singular Mechanisms Imply Cross-Resistance? J. Appl. Microbiol. 2002, 92, 98S–110S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutte, K.M.; Fisher, D.J.; Burdick, M.D.; Mehrad, B.; Mathers, A.J.; Mann, B.J.; Nakamoto, R.K.; Hughes, M.A. Escherichia coli Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complex Is an Important Component of CXCL10-Mediated Antimicrobial Activity. Infect. Immun. 2016, 84, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Westfall, C.S.; Levin, P.A. Comprehensive Analysis of Central Carbon Metabolism Illuminates Connections between Nutrient Availability, Growth Rate, and Cell Morphology in Escherichia coli. PLoS Genet. 2018, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Su, Y.-B.; Peng, B.; Li, H.; Cheng, Z.-X.; Zhang, T.-T.; Zhu, J.-X.; Li, D.; Li, M.-Y.; Ye, J.-Z.; Du, C.-C.; et al. Pyruvate Cycle Increases Aminoglycoside Efficacy and Provides Respiratory Energy in Bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E1578–E1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yang, Y.; Mi, J.; Liang, J.; Liao, X.; Ma, B.; Zou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liang, J.; Wu, Y. Changes in the Carbon Metabolism of Escherichia coli During the Evolution of Doxycycline Resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gil-Gil, T.; Corona, F.; Martínez, J.L.; Bernardini, A. The Inactivation of Enzymes Belonging to the Central Carbon Metabolism Is a Novel Mechanism of Developing Antibiotic Resistance. mSystems 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crabbé, A.; Ostyn, L.; Staelens, S.; Rigauts, C.; Risseeuw, M.; Dhaenens, M.; Daled, S.; Van Acker, H.; Deforce, D.; Van Calenbergh, S.; et al. Host Metabolites Stimulate the Bacterial Proton Motive Force to Enhance the Activity of Aminoglycoside Antibiotics. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martins, D.; Nguyen, D. Stimulating Central Carbon Metabolism to Re-Sensitize Pseudomonas aeruginosa to Aminoglycosides. Cell. Chem. Biol. 2017, 24, 122–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Battesti, A.; Majdalani, N.; Gottesman, S. Stress Sigma Factor RpoS Degradation and Translation Are Sensitive to the State of Central Metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 5159–5164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lucas, A.D. Environmental Fate of Polyhexamethylene Biguanide. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2012, 88, 322–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schug, A.R.; Bartel, A.; Scholtzek, A.D.; Meurer, M.; Brombach, J.; Hensel, V.; Fanning, S.; Schwarz, S.; Feßler, A.T. Biocide Susceptibility Testing of Bacteria: Development of a Broth Microdilution Method. Vet. Microbiol. 2020, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulton, C.S.; Higgins, C.F.; Sharp, P.M. ERIC Sequences: A Novel Family of Repetitive Elements in the Genomes of Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium and Other Enterobacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 1991, 5, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid Prokaryotic Genome Annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and Accurate Short Read Alignment with Burrows-Wheeler Transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Koboldt, D.C.; Zhang, Q.; Larson, D.E.; Shen, D.; McLellan, M.D.; Lin, L.; Miller, C.A.; Mardis, E.R.; Ding, L.; Wilson, R.K. VarScan 2: Somatic Mutation and Copy Number Alteration Discovery in Cancer by Exome Sequencing. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Strain | AMP | AZI | FOT | TAZ | CHL | CIP | COL | GEN | MER | NAL | SMX | TET | TIG | TMP | PHMB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ec04 | 8 | 8 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.015 | 1 | 1 | 0.03 | 4 | 16 | 64 | 0.25 | 1 | 1.5625 |

| Ec04m1 | 4 | 8 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.015 | 1 | 8 | 0.03 | 4 | 16 | 64 | 0.5 | 4 | 3.125 |

| Ec04m1_D2 | 4 | 8 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.03 | 1 | 8 | 0.03 | 4 | 32 | 64 | 0.5 | 4 | 3.125 |

| Ec04m1_D5 | 2 | 8 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.03 | 1 | 8 | 0.03 | 4 | 32 | 64 | 0.25 | 4 | 3.125 |

| Ec04m1_D7 | 4 | 8 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.03 | 1 | 8 | 0.03 | 4 | 32 | 64 | 0.25 | 4 | 3.125 |

| Ec04m1_D10 | 4 | 8 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.03 | 1 | 8 | 0.03 | 4 | 32 | 64 | 0.25 | 4 | 3.125 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cuzin, C.; Houée, P.; Lucas, P.; Blanchard, Y.; Soumet, C.; Bridier, A. Selection of a Gentamicin-Resistant Variant Following Polyhexamethylene Biguanide (PHMB) Exposure in Escherichia coli Biofilms. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 553. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/antibiotics10050553

Cuzin C, Houée P, Lucas P, Blanchard Y, Soumet C, Bridier A. Selection of a Gentamicin-Resistant Variant Following Polyhexamethylene Biguanide (PHMB) Exposure in Escherichia coli Biofilms. Antibiotics. 2021; 10(5):553. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/antibiotics10050553

Chicago/Turabian StyleCuzin, Clémence, Paméla Houée, Pierrick Lucas, Yannick Blanchard, Christophe Soumet, and Arnaud Bridier. 2021. "Selection of a Gentamicin-Resistant Variant Following Polyhexamethylene Biguanide (PHMB) Exposure in Escherichia coli Biofilms" Antibiotics 10, no. 5: 553. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/antibiotics10050553