An Approach to Measuring Colistin Plasma Levels Regarding the Treatment of Multidrug-Resistant Bacterial Infection

Abstract

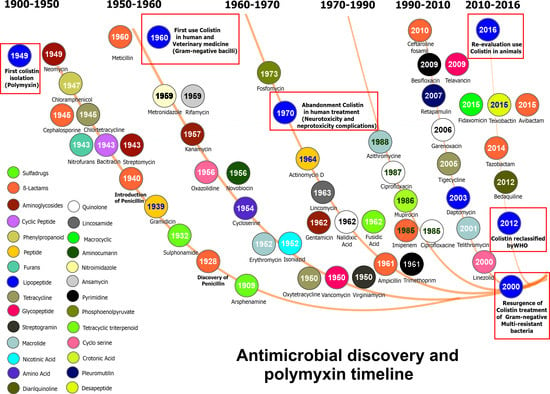

:1. Introduction

2. Colistin Used in Managing MDR Infection

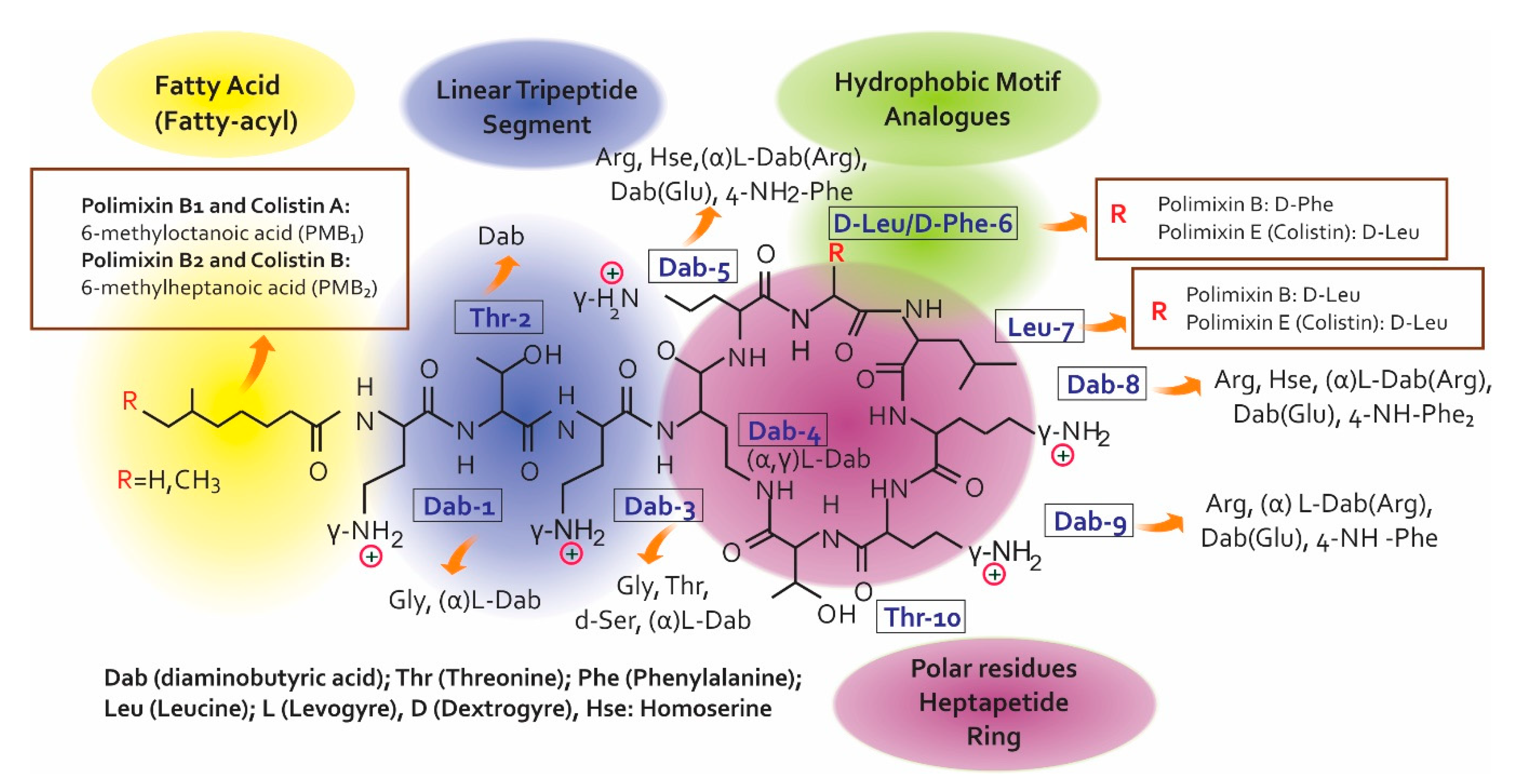

2.1. Colistin’s Chemical Structure

2.2. Mechanism of Action

2.3. Colistin Resistance Mechanisms

3. Clinical Management of Colistin

3.1. Pharmacokinetics (PK)

3.1.1. Healthy Volunteers

3.1.2. Critically-ill Patients

3.1.3. Patients having Extremely Impaired Renal Function

3.1.4. Cystic Fibrosis Patients

3.1.5. Burn Patients

4. Colistin Plasma Level Measurements

4.1. Analysis Methods

4.2. Difficulty Regarding Measurement

4.3. The Importance of Measurement

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Antimicrobial resistance. Global Report on Surveillance. Bull. World Health Organ. 2014, 61, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States; 2013 Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Velkov, T.; Roberts, K.D.; Nation, R.L.; Wang, J.; Thompson, P.E.; Li, J. Teaching ‘old’ polymyxins new tricks: New-generation lipopeptides targeting gram-negative ‘superbugs’. ACS Chem. Biol. 2014, 9, 1172–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedict, R.G.; Langlykke, A.F. Antibiotic activity of Bacillus polymyxa. J. Bacteriol. 1947, 54, 24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brink, A.J.; Richards, G.A.; Colombo, G.; Bortolotti, F.; Colombo, P.; Jehl, F. Multicomponent antibiotic substances produced by fermentation: Implications for regulatory authorities, critically ill patients and generics. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2014, 43, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velkov, T.; Roberts, K.D.; Nation, R.L.; Thompson, P.E.; Li, J. Pharmacology of polymyxins: New insights into an ‘old’ class of antibiotics. Future Microbiol. 2013, 8, 711–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallardo-Godoy, A.; Muldoon, C.; Becker, B.; Elliott, A.G.; Lash, L.H.; Huang, J.X.; Butler, M.S.; Pelingon, R.; Kavanagh, A.M.; Ramu, S.; et al. Activity and Predicted Nephrotoxicity of Synthetic Antibiotics Based on Polymyxin B. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 1068–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsubery, H.; Ofek, I.; Cohen, S.; Fridkin, M. N-terminal modifications of Polymyxin B nonapeptide and their effect on antibacterial activity. Peptides 2001, 22, 1675–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velkov, T.; Thompson, P.E.; Nation, R.L.; Li, J. Structure—Activity relationships of polymyxin antibiotics. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 1898–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nation, R.L.; Velkov, T.; Li, J. Colistin and polymyxin B: Peas in a pod, or chalk and cheese? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 59, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirel, L.; Jayol, A.; Nordmann, P. Polymyxins: Antibacterial Activity, Susceptibility Testing, and Resistance Mechanisms Encoded by Plasmids or Chromosomes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 30, 557–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pristovšek, P.; Kidrič, J. Solution structure of polymyxins B and E and effect of binding to lipopolysaccharide: An NMR and molecular modeling study. J. Med. Chem. 1999, 42, 4604–4613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Pharmacopoeia 8.0. Monographs for Colistimethate Sodium and Colisitin Sulfate. Available online: http://online6.edqm.eu/ep800/ (accessed on 29 May 2019).

- European Pharmacopoeia 8.0. Monograph for Polymyxin B Sulfate. Available online: http://online6.edqm.eu/ep800/ (accessed on 21 February 2019).

- United States Pharmacopoeia 36. Monographs for Colistimethate Sodium and Colistin Sulfate. Available online: https://www.uspnf.com/official-text/proposal-statuscommentary/usp-36-nf-31 (accessed on 21 February 2019).

- United States Pharmacopoeia 36. Monograph for Polymyxin B Sulfate. Available online: https://www.uspnf.com/official-text/proposal-statuscommentary/usp-36-nf-31 (accessed on 21 February 2019).

- Kadar, B.; Kocsis, B.; Nagy, K.; Szabo, D. The renaissance of polymyxins. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013, 20, 3759–3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, R.A.; Chopra, I. Leakage of periplasmic proteins from Escherichia coli mediated by polymyxin B nonapeptide. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1986, 29, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, J.; Nation, R.L.; Milne, R.W.; Turnidge, J.D.; Coulthard, K. Evaluation of colistin as an agent against multi-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2005, 25, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhouma, M.; Beaudry, F.; Letellier, A. Resistance to colistin: What is the fate for this antibiotic in pig production? Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2016, 48, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snesrud, E.; Maybank, R.; Kwak, Y.I.; Jones, A.R.; Hinkle, M.K.; McGann, P. Chromosomally Encoded mcr-5 in Colistin-Nonsusceptible Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e00679-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirel, L.; Jayol, A.; Bontron, S.; Villegas, M.V.; Ozdamar, M.; Turkoglu, S.; Nordmann, P. The mgrB gene as a key target for acquired resistance to colistin in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, C.; Pragasam, A.K.; Anandan, S.; Veeraraghavan, B. mgrB as Hotspot for Insertion Sequence Integration: Change Over from Multidrug-Resistant to Extensively Drug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae? Microb. Drug Resist. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurtop, E.; Bayindir Bilman, F.; Menekse, S.; Kurt Azap, O.; Gonen, M.; Ergonul, O.; Can, F. Promoters of Colistin Resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii Infections. Microb. Drug Resist. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlynarcik, P.; Kolar, M. Molecular mechanisms of polymyxin resistance and detection of mcr genes. Biomed. Pap. 2019, 163, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mavrici, D.; Yambao, J.C.; Lee, B.G.; Quinones, B.; He, X. Screening for the presence of mcr-1/mcr-2 genes in Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli recovered from a major produce-production region in California. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirel, L.; Larpin, Y.; Dobias, J.; Stephan, R.; Decousser, J.W.; Madec, J.Y.; Nordmann, P. Rapid Polymyxin NP test for the detection of polymyxin resistance mediated by the mcr-1/mcr-2 genes. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2018, 90, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trimble, M.J.; Mlynarcik, P.; Kolar, M.; Hancock, R.E. Polymyxin: Alternative Mechanisms of Action and Resistance. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2016, 6, a025288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Markou, N.; Fousteri, M.; Markantonis, S.L.; Zidianakis, B.; Hroni, D.; Boutzouka, E.; Baltopoulos, G. Colistin pharmacokinetics in intensive care unit patients on continuous venovenous haemodiafiltration: An observational study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 2459–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, A.; Rocha, M.; Alves, G.; Falcão, A.; Fortuna, A. Development and validation of an HPLC-FLD technique for colistin quantification and its plasma monitoring in hospitalized patients. Anal. Methods 2018, 10, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jitmuang, A.; Nation, R.L.; Koomanachai, P.; Chen, G.; Lee, H.J.; Wasuwattakul, S.; Sritippayawan, S.; Li, J.; Thamlikitkul, V.; Landersdorfer, C.B. Extracorporeal clearance of colistin methanesulphonate and formed colistin in end-stage renal disease patients receiving intermittent haemodialysis: Implications for dosing. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 1804–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niece, K.L.; Akers, K.S. Preliminary Method for Direct Quantification of Colistin Methanesulfonate by Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR FT-IR). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 5542–5547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, M.; Gregoire, N.; Mégarbane, B.; Gobin, P.; Balayn, D.; Marchand, S.; Mimoz, O.; Couet, W. Population pharmacokinetics of colistin methanesulfonate and colistin in critically ill patients with acute renal failure requiring intermittent hemodialysis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 1788–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.A.; Westman, E.L.; Wright, G.D. The antibiotic resistome: what’s new? Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2014, 21, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, B.; Cain, A.K.; Doerrler, W.T.; Boinett, C.J.; Fookes, M.C.; Parkhill, J.; Guardabassi, L. The secondary resistome of multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerrler, W.T.; Sikdar, R.; Kumar, S.; Boughner, L.A. New functions for the ancient DedA membrane protein family. J. Bacteriol. 2013, 195, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Doerrler, W.T. Members of the conserved DedA family are likely membrane transporters and are required for drug resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaitan, A.O.; Morand, S.; Rolain, J.-M. Mechanisms of polymyxin resistance: Acquired and intrinsic resistance in bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nummila, K.; Kilpeläinen, I.; Zähringer, U.; Vaara, M.; Helander, I.M. Lipopolysaccharides of polymyxin B-resistant mutants of Escherichia coii are extensively substituted by 2-aminoethyl pyrophosphate and contain aminoarabinose in lipid A. Mol. Microbiol. 1995, 16, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghapour, Z.; Gholizadeh, P.; Ganbarov, K.; Bialvaei, A.Z.; Mahmood, S.S.; Tanomand, A.; Yousefi, M.; Asgharzadeh, M.; Yousefi, B.; Kafil, H.S. Molecular mechanisms related to colistin resistance in Enterobacteriaceae. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 965–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.S.; Liu, M.C.; Teng, L.J.; Wang, W.B.; Hsueh, P.R.; Liaw, S.J. Proteus mirabilis pmrI, an RppA-regulated gene necessary for polymyxin B resistance, biofilm formation, and urothelial cell invasion. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 1564–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaitan, A.O.; Dia, N.M.; Gautret, P.; Benkouiten, S.; Belhouchat, K.; Drali, T.; Parola, P.; Brouqui, P.; Memish, Z.; Raoult, D.; et al. Acquisition of extended-spectrum cephalosporin- and colistin-resistant Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype Newport by pilgrims during Hajj. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2015, 45, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayol, A.; Poirel, L.; Brink, A.; Villegas, M.V.; Yilmaz, M.; Nordmann, P. Resistance to colistin associated with a single amino acid change in protein PmrB among Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates of worldwide origin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 4762–4766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaitan, A.O.; Morand, S.; Rolain, J.M. Emergence of colistin-resistant bacteria in humans without colistin usage: A new worry and cause for vigilance. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2016, 47, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.N.; Klein, D.R.; Kazi, M.I.; Guerin, F.; Cattoir, V.; Brodbelt, J.S.; Boll, J.M. Colistin heteroresistance in Enterobacter cloacae is regulated by PhoPQ-dependent 4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose addition to lipid A. Mol. Microbiol. 2019, 111, 1604–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.H.; Lin, T.L.; Lin, Y.T.; Wang, J.T. Amino Acid Substitutions of CrrB Responsible for Resistance to Colistin through CrrC in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 3709–3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jaidane, N.; Bonnin, R.A.; Mansour, W.; Girlich, D.; Creton, E.; Cotellon, G.; Chaouch, C.; Boujaafar, N.; Bouallegue, O.; Naas, T. Genomic Insights into Colistin-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae from a Tunisian Teaching Hospital. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e01601-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, G.J.; Domingues, S. Interplay between Colistin Resistance, Virulence and Fitness in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antibiotics (Basel) 2017, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Ribeiro, A.A.; Lin, S.; Cotter, R.J.; Miller, S.I.; Raetz, C.R. Lipid a modifications in polymyxin-resistant Salmonella typhimurium PmrA-dependent 4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose, and phosphoethanolamine incorporation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 43111–43121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, J.; Yin, W.; Wang, S.; Zhang, S.; Shen, J.; Shen, Z.; Wang, Y. Emergence of a novel mobile colistin resistance gene, mcr-8, in NDM-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2018, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llobet, E.; Martinez-Moliner, V.; Moranta, D.; Dahlstrom, K.M.; Regueiro, V.; Tomas, A.; Cano, V.; Perez-Gutierrez, C.; Frank, C.G.; Fernandez-Carrasco, H.; et al. Deciphering tissue-induced Klebsiella pneumoniae lipid A structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E6369–E6378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malott, R.J.; Steen-Kinnaird, B.R.; Lee, T.D.; Speert, D.P. Identification of hopanoid biosynthesis genes involved in polymyxin resistance in Burkholderia multivorans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, L.; Meibohm, B. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic correlations of therapeutic peptides. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2013, 52, 855–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couet, W.; Grégoire, N.; Gobin, P.; Saulnier, P.J.; Frasca, D.; Marchand, S.; Mimoz, O. Pharmacokinetics of colistin and colistimethate sodium after a single 80-mg intravenous dose of CMS in young healthy volunteers. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 89, 875–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, M.A.; Huang, J.X.; Cooper, M.A.; Roberts, K.D.; Thompson, P.E.; Nation, R.L.; Li, J.; Velkov, T. Structure-activity relationships for the binding of polymyxins with human α-1-acid glycoprotein. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2012, 84, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Milne, R.W.; Nation, R.L.; Turnidge, J.D.; Smeaton, T.C.; Coulthard, K. Use of high-performance liquid chromatography to study the pharmacokinetics of colistin sulfate in rats following intravenous administration. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 1766–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, S.E.; Wang, J.; Nguyen, V.T.; Turnidge, J.D.; Li, J.; Nation, R.L. New pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies of systemically administered colistin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii in mouse thigh and lung infection models: Smaller response in lung infection. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 3291–3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.F.; Karaiskos, I.; Plachouras, D.; Karvanen, M.; Pontikis, K.; Jansson, B.; Papadomichelakis, E.; Antoniadou, A.; Giamarellou, H.; Armaganidis, A.; et al. Application of a loading dose of colistin methanesulfonate in critically ill patients: population pharmacokinetics, protein binding, and prediction of bacterial kill. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 4241–4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imberti, R.; Cusato, M.; Villani, P.; Carnevale, L.; Iotti, G.A.; Langer, M.; Regazzi, M. Steady-state pharmacokinetics and BAL concentration of colistin in critically Ill patients after IV colistin methanesulfonate administration. Chest 2010, 138, 1333–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boisson, M.; Jacobs, M.; Grégoire, N.; Gobin, P.; Marchand, S.; Couet, W.; Mimoz, O. Comparison of intrapulmonary and systemic pharmacokinetics of colistin methanesulfonate (CMS) and colistin after aerosol delivery and intravenous administration of CMS in critically ill patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 7331–7339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yapa, S.W.S.; Li, J.; Patel, K.; Wilson, J.W.; Dooley, M.J.; George, J.; Clark, D.; Poole, S.; Williams, E.; Porter, C.J.; et al. Pulmonary and systemic pharmacokinetics of inhaled and intravenous colistin methanesulfonate in cystic fibrosis patients: Targeting advantage of inhalational administration. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 2570–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markantonis, S.L.; Markou, N.; Fousteri, M.; Sakellaridis, N.; Karatzas, S.; Alamanos, I.; Dimopoulou, E.; Baltopoulos, G. Penetration of colistin into cerebrospinal fluid. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 4907–4910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaka, M.; Markantonis, S.L.; Fousteri, M.; Zygoulis, P.; Panidis, D.; Karvouniaris, M.; Makris, D.; Zakynthinos, E. Combined intravenous and intraventricular administration of colistin methanesulfonate in critically ill patients with central nervous system infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 1938–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imberti, R.; Cusato, M.; Accetta, G.; Marinò, V.; Procaccio, F.; Del Gaudio, A.; Iotti, G.A.; Regazzi, M. Pharmacokinetics of colistin in cerebrospinal fluid after intraventricular administration of colistin methanesulfonate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 4416–4421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Wu, X.J.; Fan, Y.X.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Guo, B.N.; Yu, J.C.; Cao, G.Y.; Chen, Y.C.; Wu, J.F.; Shi, Y.G.; et al. Pharmacokinetics of colistin methanesulfonate (CMS) in healthy Chinese subjects after single and multiple intravenous doses. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2018, 51, 714–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garonzik, S.M.; Li, J.; Thamlikitkul, V.; Paterson, D.L.; Shoham, S.; Jacob, J.; Silveira, F.P.; Forrest, A.; Nation, R.L. Population pharmacokinetics of colistin methanesulfonate and formed colistin in critically ill patients from a multicenter study provide dosing suggestions for various categories of patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 3284–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grégoire, N.; Mimoz, O.; Mégarbane, B.; Comets, E.; Chatelier, D.; Lasocki, S.; Gauzit, R.; Balayn, D.; Gobin, P.; Marchand, S.; et al. New colistin population pharmacokinetic data in critically ill patients suggesting an alternative loading dose rationale. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 7324–7330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plachouras, D.; Karvanen, M.; Friberg, L.E.; Papadomichelakis, E.; Antoniadou, A.; Tsangaris, I.; Karaiskos, I.; Poulakou, G.; Kontopidou, F.; Armaganidis, A.; et al. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of colistin methanesulfonate and colistin after intravenous administration in critically ill patients with infections caused by gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 3430–3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaiskos, I.; Friberg, L.E.; Pontikis, K.; Ioannidis, K.; Tsagkari, V.; Galani, L.; Kostakou, E.; Baziaka, F.; Paskalis, C.; Koutsoukou, A.; et al. Colistin Population Pharmacokinetics after Application of a Loading Dose of 9 MU Colistin Methanesulfonate in Critically Ill Patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 7240–7248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Menna, P.; Salvatorelli, E.; Mattei, A.; Cappiello, D.; Minotti, G.; Carassiti, M. Modified Colistin Regimen for Critically Ill Patients with Acute Renal Impairment and Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy. Chemotherapy 2018, 63, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchand, S.; Frat, J.P.; Petitpas, F.; Lemaître, F.; Gobin, P.; Robert, R.; Mimoz, O.; Couet, W. Removal of colistin during intermittent haemodialysis in two critically ill patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010, 65, 1836–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luque, S.; Sorli, L.; Li, J.; Collado, S.; Barbosa, F.; Berenguer, N.; Horcajada, J.P.; Grau, S. Effective removal of colistin methanesulphonate and formed colistin during intermittent haemodialysis in a patient infected by polymyxin-only-susceptible Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Chemother. 2014, 26, 122–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Coulthard, K.; Milne, R.; Nation, R.L.; Conway, S.; Peckham, D.; Etherington, C.; Turnidge, J. Steady-state pharmacokinetics of intravenous colistin methanesulphonate in patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003, 52, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Han, S.; Jeon, S.; Hong, T.; Song, W.; Woo, H.; Yim, D.S. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of colistin in burn patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 2141–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelesidis, T.; Falagas, M.E. The safety of polymyxin antibiotics. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2015, 14, 1687–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolinsky, E.; Hines, J.D. Neurotoxic and nephrotoxic effects of colistin in patients with renal disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1962, 266, 759–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch-Weser, J.A.N.; Sidel, V.W.; Federman, E.B.; Kanarek, P.; Finer, D.C.; Eaton, A.N.N.E. Adverse Effects of Sodium ColistimethateManifestations and Specific Reaction Rates During 317 Courses of Therapy. Ann. Intern. Med. 1970, 72, 857–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falagas, M.E.; Kasiakou, S.K. Toxicity of polymyxins: A systematic review of the evidence from old and recent studies. Crit. Care 2006, 10, R27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florescu, D.F.; Qiu, F.; McCartan, M.A.; Mindru, C.; Fey, P.D.; Kalil, A.C. What is the efficacy and safety of colistin for the treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia? A systematic review and meta-regression. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 54, 670–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, W.J.; Wang, F.; Tang, L.; Bakker, J.; Liu, J.C. Colistin for the treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2014, 44, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falagas, M.E.; Rafailidis, P.I.; Ioannidou, E.; Alexiou, V.G.; Matthaiou, D.K.; Karageorgopoulos, D.E.; Kapaskelis, A.; Nikita, D.; Michalopoulos, A. Colistin therapy for microbiologically documented multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections: A retrospective cohort study of 258 patients. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2010, 35, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elias, L.S.; Konzen, D.; Krebs, J.M.; Zavascki, A.P. The impact of polymyxin B dosage on in-hospital mortality of patients treated with this antibiotic. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010, 65, 2231–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandri, A.M.; Landersdorfer, C.B.; Jacob, J.; Boniatti, M.M.; Dalarosa, M.G.; Falci, D.R.; Behle, T.F.; Bordinhão, R.C.; Wang, J.; Forrest, A.; et al. Population pharmacokinetics of intravenous polymyxin B in critically ill patients: Implications for selection of dosage regimens. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 57, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, V.H.; Schilling, A.N.; Vo, G.; Kabbara, S.; Kwa, A.L.; Wiederhold, N.P.; Lewis, R.E. Pharmacodynamics of polymyxin B against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 3624–3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falagas, M.E.; Rizos, M.; Bliziotis, I.A.; Rellos, K.; Kasiakou, S.K.; Michalopoulos, A. Toxicity after prolonged (more than four weeks) administration of intravenous colistin. BMC Infect. Dis. 2005, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartzell, J.D.; Neff, R.; Ake, J.; Howard, R.; Olson, S.; Paolino, K.; Vishnepolsky, M.; Weintrob, A.; Wortmann, G. Nephrotoxicity Associated with Intravenous Colistin (Colistimethate Sodium) Treatment at a Tertiary Care Medical Center. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 48, 1724–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.R.; Lewis, S.A. Colistin interactions with the mammalian urothelium. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2004, 286, C913–C922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ito, J.; Johnson, W.W.; Roy, S. Colistin nephrotoxicity: Report of a case with light and electron microscopic studies. Acta Pathol. Jpn. 1969, 19, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deryke, C.A.; Crawford, A.J.; Uddin, N.; Wallace, M.R. Colistin Dosing and Nephrotoxicity in a Large Community Teaching Hospital. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 4503–4505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Phe, K.; Lee, Y.; McDaneld, P.M.; Prasad, N.; Yin, T.; Figueroa, D.A.; Musick, W.L.; Cottreau, J.M.; Hu, M.; Tam, V.H. In vitro assessment and multicenter cohort study of comparative nephrotoxicity rates associated with colistimethate versus polymyxin B therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 2740–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, J.M.; Haynes, K.; Gallagher, J.C. Emergent renal dysfunction with colistin pharmacotherapy. Pharmacotherapy 2013, 33, 812–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phe, K.; Johnson, M.L.; Palmer, H.R.; Tam, V.H. Validation of a model to predict the risk of nephrotoxicity in patients receiving colistin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 6946–6948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falagas, M.E.; Fragoulis, K.N.; Kasiakou, S.K.; Sermaidis, G.J.; Michalopoulos, A. Nephrotoxicity of intravenous colistin: A prospective evaluation. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2005, 26, 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A.; Soriano, S.M.; Song, M.; Chihara, S. Intravenous colistin-induced acute respiratory failure: A case report and a review of literature. Int. J. Crit. Illn. Inj. Sci. 2014, 4, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Decker, D.A.; Fincham, R.W. Respiratory Arrest in Myasthenia Gravis with Colistimethate Therapy. Arch. Neurol. 1971, 25, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gales, A.C.; Reis, A.O.; Jones, R.N. Contemporary assessment of antimicrobial susceptibility testing methods for polymyxin B and colistin: Review of available interpretative criteria and quality control guidelines. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, B.; Karvanen, M.; Cars, O.; Plachouras, D.; Friberg, L.E. Quantitative analysis of colistin A and colistin B in plasma and culture medium using a simple precipitation step followed by LC/MS/MS. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2009, 49, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falagas, M.E.; Kasiakou, S.K.; Saravolatz, L.D. Colistin: The revival of polymyxins for the management of multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 40, 1333–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decolin, D.; Leroy, P.; Nicolas, A.; Archimbault, P. Hyphenated liquid chromatographic method for the determination of colistin residues in bovine tissues. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 1997, 35, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wootton, M.; Holt, H.; Macgowan, A. Development of a novel assay method for colistin sulphomethate. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2005, 11, 243–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Simon, H.J.; Yin, E.J. Microbioassay of antimicrobial agents. Appl. Microbiol. 1970, 19, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gobin, P.; Lemaître, F.; Marchand, S.; Couet, W.; Olivier, J.-C. Assay of colistin and colistin methanesulfonate in plasma and urine by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 1941–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domes, C.; Domes, R.; Popp, J.; Pletz, M.W.; Frosch, T. Ultrasensitive Detection of Antiseptic Antibiotics in Aqueous Media and Human Urine Using Deep UV Resonance Raman Spectroscopy. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 9997–10003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Nation, R.L.; Turnidge, J.D.; Milne, R.W.; Coulthard, K.; Rayner, C.R.; Paterson, D.L. Colistin: The re-emerging antibiotic for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2006, 6, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarot, I.; Storme-Paris, I.; Chaminade, P.; Estevenon, O.; Nicolas, A.; Rieutord, A. Simultaneous quantitation of tobramycin and colistin sulphate by HPLC with evaporative light scattering detection. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2009, 50, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, B.C.; Falcón, M.G.; Perez-Lamela, C.; Comesaña, M.R.; Gándara, J.S. Quantitative analysis of colistin and tiamulin in liquid and solid medicated premixes by HPLC with diode-array detection. Chromatographia 2001, 53, S460–S463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gikas, E.; Bazoti, F.N.; Katsimardou, M.; Anagnostopoulos, D.; Papanikolaou, K.; Inglezos, I.; Skoutelis, A.; Daikos, G.L.; Tsarbopoulos, A. Determination of colistin A and colistin B in human plasma by UPLC–ESI high resolution tandem MS: Application to a pharmacokinetic study. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2013, 83, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morovján, G.; Csokan, P.; Nemeth-Konda, L. HPLC determination of colistin and aminoglycoside antibiotics in feeds by post-column derivatization and fluorescence detection. Chromatographia 1998, 48, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, C.; Fassauer, G.; Gerecke, H.; Jira, T.; Remane, Y.; Frontini, R.; Byrne, J.; Reinhardt, R. Purity determination of amphotericin B, colistin sulfate and tobramycin sulfate in a hydrophilic suspension by HPLC. J. Chromatogr. B 2015, 990, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, L.M.; Ly, N.; Anderson, D.; Yang, J.C.; Macander, L.; Jarkowski, A., III; Forrest, A.; Bulitta, J.B.; Tsuji, B.T. Resurgence of colistin: A review of resistance, toxicity, pharmacodynamics, and dosing. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2010, 30, 1279–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chepyala, D.; Tsai, I.-L.; Sun, H.-Y.; Lin, S.-W.; Kuo, C.-H. Development and validation of a high-performance liquid chromatography-fluorescence detection method for the accurate quantification of colistin in human plasma. J. Chromatogr. B 2015, 980, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spapen, H.; Jacobs, R.; Van Gorp, V.; Troubleyn, J.; Honoré, P.M. Renal and neurological side effects of colistin in critically ill patients. Ann. Intensive Care 2011, 1, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nation, R.L.; Li, J. Colistin in the 21st century. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 22, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.; Gosbell, I.B.; Kelly, J.A.; Boyle, M.J.; Ferguson, J.K. Cure of multiresistant Acinetobacter baumannii central nervous system infections with intraventricular or intrathecal colistin: Case series and literature review. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006, 58, 1078–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genes Involved | Resistance Mechanism | Bacteria | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| LPS modifications | |||

| arnBCADTEF operon and pmrE | Modification of the lipid A with aminoarabinose | Salmonella enterica, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, Proteeae bacteria, Serratia marcescens and P. aeruginosa | [38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45] |

| crrB (crrC) | The regulatory systems of two-component PhoP-PhoQ and PmrA-PmrB (response regulator/sensor kinase) | K. pneumoniae CG43 | [25,46] |

| pmrAB, pmrD, phoPQ, parRS, mcr | L-Ara4N and PEtn modification of lipid A | E. coli, Salmonella enterica, P. aeruginosa | [25,40,47] |

| ParR/ParS, ColR/ColS and CprR/CprS | LPS modification with aminoarabinose | P. aeruginosa | [11,21] |

| mgrB | Structural modifications of the lipid A subunit | K. pneumonia | [22,23] |

| lpxACD, lptD | Loss of LPS | Acinetobacter baumannii | [24,48] |

| pmrC | Modification of the lipid A phosphoethanolamine | S. enterica, K. pneumoniae, E. coli and Acinetobacter baumannii | [38,49] |

| mcr-1 to mcr-8 | Inactivation of lipid A biosynthesis | E. Coli and K. pneumonia | [11,50] |

| Pag, PagL, LpxM and LpxO | Modifications on cell surface regarding electrostatic repulsion of colistin Decreasing membrane fluidity/permeability | K. pneumoniae, E. coli, S. enterica and Legionella pneumophila | [25,51] |

| Bmul_2133/Bmul_2134 | phosphorylation, dephosphorylation, glycylation and glucosylation of lipid A | Burkholderia multivorans | [28,52] |

| Repulsion mechanism | |||

| dlt-ABCD, graXSR, dra/dlt, liaSR and CiaR operons | Adding D-alanine (D-Ala) to teichoic acids, thereby increasing net positive charge | Staphylococcus aureus, Bordetella pertussis, Streptococcus gordonii, Listeria monocytogenes and Group B Streptococcus | [53,54] |

| Membrane remodelling | |||

| siaD, cps operon, ompA, kpnEF, phoPQ and rcs | Loss of polymyxin target and capsule polysaccharide (CPS) overproduction | Neisseria meningitidis, K. pneumoniae and S. enterica | [40] |

| virB, suhB Bc, bvrRS, epsC-N, cgh, vacJ, waaL, rfbA, ompW, micF, pilMNOPQ operon, parRS, rsmA, bveA, ydeI (omdA), ompD (nmpC), ygiW (visP), ompF, rcs | Altered membrane composition | Brucella ovis, S. enterica, Brucella melitensis, Burkholderia cenocepacia, Vibrio cholerae, Brucella abortus, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, N. meningitidis and Brucella melitensis | [29,40] |

| cas9, tracrRNA, scaRNA, Lol, TolQRA | Altered membrane integrity | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Vibrio fischeri, B. cenocepacia, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, Salmonella Typhimurium, Campylobacter jejuni and Haemophilus influenzae | |

| spgM, pgm, hldA, hldD, oprH, cj1136, waaF, lgtF, galT, cstII, galU | Lipooligosaccharide (LOS) and LPS modification | ||

| Modifications to OM porins and overexpression of efflux pump systems | |||

| OmpU, OmpA and PorB | Mutations in outer membrane porins | N. meningitidis and V. cholerae | [32] |

| MtrC –MtrD –MtrE, RosAB, AcrAB–TolC | An important role in tolerance toward polymyxin B | E. coli | [33] |

| NorM, KpnEF and VexAB | Neisseria gonorrhoeae | ||

| dedA | playing an important role in membrane homeostasis | E. coli | [34,35,36,37] |

| Colistin Binding (CB) | Population | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 55% | Dogs, calves | [56] |

| 91% | Mice | [57] |

| 59%–74% | Critically ill patients | [58] |

| Tissue | Characteristics | Ref |

|---|---|---|

| The lungs | Imberti et al., could not measure colistin in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) after repeated IV doses of 2 million international units (MIU) CMS every 8 h to critically-ill patients. Boisson et al., reported 0.1 and 29 mg/L colistin concentrations in steady-state epithelial lining fluid (ELF). Yapa et al., reported lower than 1 mg/L colistin concentrations in sputum after a single IV dose of 5 MIU CMS. No active transport has yet been reported for colistin’s passage across the pulmonary barrier. | [59] [60] [61] |

| The central nervous system (CNS) | Passage across the blood-brain barrier BBB becomes limited after repeated IV doses (<5%) in critically-ill patients. Inflamed meningeal membranes increased to 11% concentration in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), even greater when administered by intrathecal route. CSF concentrations vary between 0.6 and 1.5 mg/L when patients are treated with IV 3 MIU CMS every 8 h plus intra-ventricular 0.125 MIU CMS every 24 h. | [62,63,64] |

| Peritoneal liquid | A case report has been published regarding a patient suffering severe peritonitis following multiple administrations of 2 MIU CMS every 8 h. Colistin became slowly distributed in the peritoneal fluid but colistin concentrations in peritoneal fluid were similar to that of steady-state plasma. | [63] |

| Parameter | Colistimethate | Colistin |

|---|---|---|

| Cmax (μg/mL) | 4.8 | 0.83 |

| Tmax (h) | - | 2.0 |

| Distribution | ||

| Vd | Vc: 8.92 L Vss: 14 L | 12.4 mL/min |

| Elimination | ||

| CL (mL/min) ErCL RCL | 148 48 103 | 48.7 46.6 1.9 |

| t1/2 (h) | 0.49 | 3.0 |

| With Maintenance Dose | References |

|---|---|

| -Cmax has been observed at the end of the infusion. -Concentrations have become reduced mono-or bi-exponentially -t1/2 = 1.9–4.5 h -Typical CMS renal clearances for patients having 120, 50 and 25 mL/min creatinine clearance values has been around 100, 50 and 25 mL/min, respectively. -CMS fraction converted into colistin has increased by 33%, 50% and 67% for each value, resulting in higher colistin concentrations for patients suffering impaired renal function. | [66] [67] |

| CMS Clearance | Colistin Clearance | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intermittent haemodialysis | 71 to 95 mL/min | 57 to 134 mL/min | [71,72] |

| Continuous venovenous haemofiltration (CVVH) | 64 mL/min | 34 mL/min | [66] |

| Continuous venovenous haemodiafiltration (CVVHDF) | -- | 50% | [29] |

| Parameter | Characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| CL| | 100 mL/min | [61] |

| Vd | 18 L | [73] |

| T1/2 | 2.5 h | [73] |

| Exposure | >39% than in healthy volunteers | [61] |

| Technique | Methodology | Results | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microbiological bioassays | Quantifying colistin in human plasma using E. coli as indicator organism | Bioassays have mainly been used regarding clinical samples—evaluating urine and serum samples—less sensitive and specific tests | [100] |

| Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) | Direct quantification of colistin methanesulfonate by attenuated total reflectance (ATR) FTIR | FTIR has enabled colistin to be detected in human plasma but must be complemented with other techniques, such as HPLC | [32] |

| High-resolution liquid chromatography (HPLC) | HPLC validation using fluorescence detection assay for quantifying colistin in plasma samples from hospitalised patients | A C18 column has been used with a mobile phase consisting of acetonitrile and water having a shorter retention time. Furthermore, this method has successfully quantified total colistin in plasma from patients treated with CMS | [30] |

| Quantifying colistin in plasma from Pseudomonas aeruginosa-infected mice | Accuracy and reproducibility have ranged from 10.1% to 11.2% with rat and urine plasma, respectively. Several antibacterial agents which have often been administered together have not interfered with the assay | [104] | |

| HPLC with evaporative light scattering detector (ELSD) | Quantifying colistin in plasma by HPLC with an ELSD | The method has proved to be specific, accurate, precise and linear | [105] |

| Diode array HPLC detector | Quantifying colistin in animal plasma by HPLC with diode array detector | Scanning in the UV 200-380 nm range, 206 and 208 nm wavelengths have enabled colistin to be quantified | [106] |

| Liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS) | Routine quantification of colistin A and B and their respective CMS A and CMS B prodrugs in human plasma and urine | Pre-validation studies have demonstrated CMS stability in biological samples and extracts, this being a key point regarding reliable quantification of colistin and CMS. The assay has proved precise/accurate and reproducible for quantifying colistin A and B and CMS A and B in plasma samples | [102] |

| Ultra-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray tandem mass spectrometry with electrospray ionisation (UPLC-ESI-MS/MS) | Quantifying colistin in human plasma by a combination of techniques UPLC-ESI- MS/MS | Validation results have shown that the method had suitable selectivity and sensitivity. The method has been successfully used with plasma samples from cystic fibrosis patients who have been treated with colistin. The PK profile has been calculated. | [107] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pacheco, T.; Bustos, R.-H.; González, D.; Garzón, V.; García, J.-C.; Ramírez, D. An Approach to Measuring Colistin Plasma Levels Regarding the Treatment of Multidrug-Resistant Bacterial Infection. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 100. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/antibiotics8030100

Pacheco T, Bustos R-H, González D, Garzón V, García J-C, Ramírez D. An Approach to Measuring Colistin Plasma Levels Regarding the Treatment of Multidrug-Resistant Bacterial Infection. Antibiotics. 2019; 8(3):100. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/antibiotics8030100

Chicago/Turabian StylePacheco, Tatiana, Rosa-Helena Bustos, Diana González, Vivian Garzón, Julio-Cesar García, and Daniela Ramírez. 2019. "An Approach to Measuring Colistin Plasma Levels Regarding the Treatment of Multidrug-Resistant Bacterial Infection" Antibiotics 8, no. 3: 100. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/antibiotics8030100