Environmental Identity and Natural Resources: A Dialogical Learning Process

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Three Types of Learning

3. Emotions and “Felt” Dilemmas

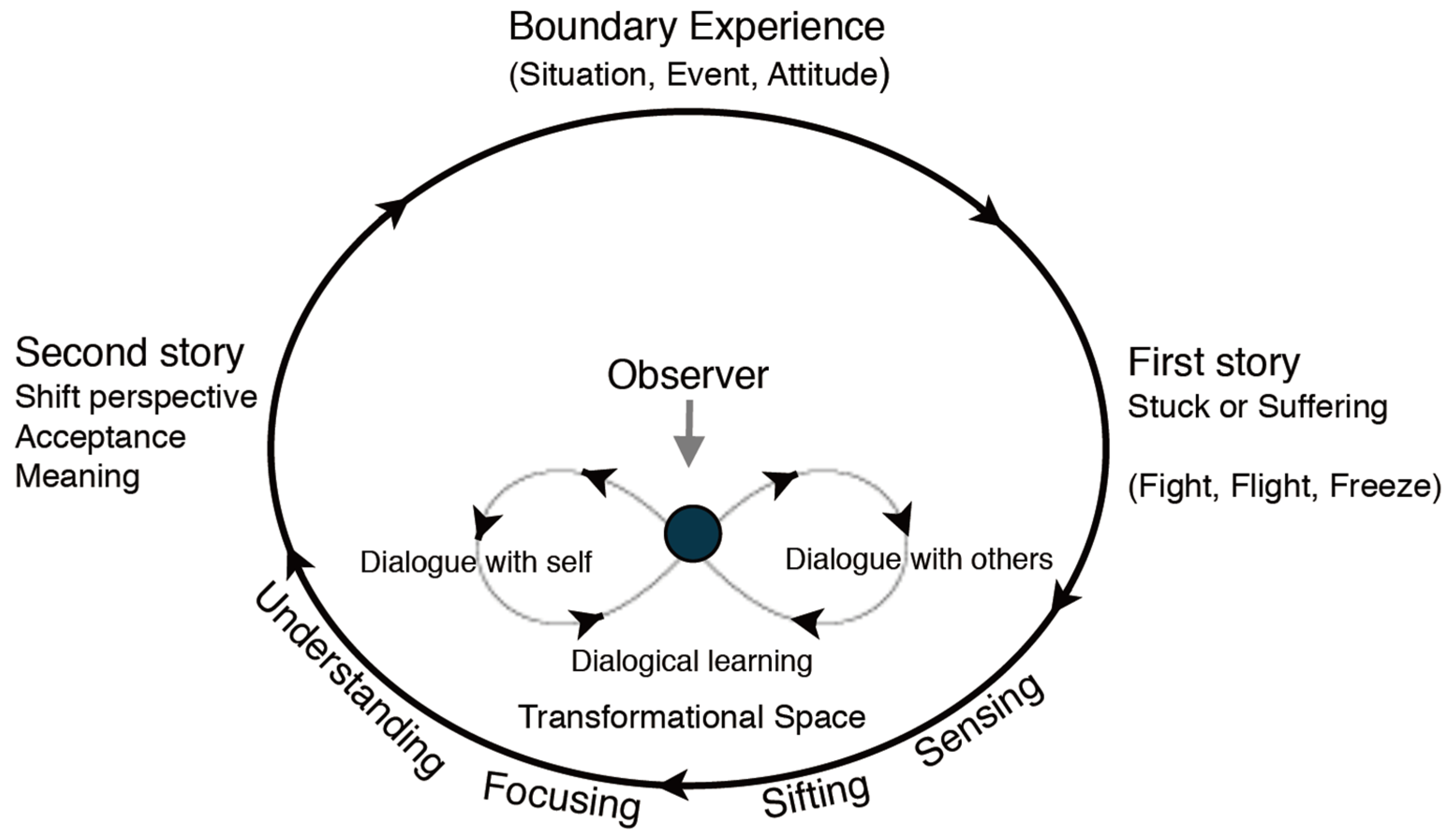

4. Dialogical Self Theory

5. A Learning Process in Four Stages

6. Characteristics of a Good Dialogue Aiming at Identity Formation

- emotions have to be valued; in other words, all those involved in a social interaction should be grateful that emotions exist;

- emotions should be treated with caution. They are often extremely powerful motives for the behavior of individuals. When environmental issues are brought to the fore, people respond with anxiety, rage, depression and panic [115]. In addition, when an emotion is ignored or even denied, it can be turned against the person or organization that allowed this denial to occur;

- emotions demand respect or, in other words, concentrated attention. Many people feel uncomfortable when someone nearby shows some emotional involvement. The tendency to quickly move on to something else is prevalent. However, if emotions are ever to become a functional part of the learning process whereby an environmental identity may be constructed, then attention has to be paid to them. One should not try to suppress emotions but rather use them to illuminate the message that they are carrying as is explained in the section on emotions and felt dilemmas.

7. Do Schools Have Room for a Good Dialogue?

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dietz, T.; Fitzgerald, A.; Shwom, R. Environmental values. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 335–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satterfield, T.; Kalov, L. Environmental values: An introduction. In The Earthscan Reader in Environmental Values; Kalof, L., Satterfield, T., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, P.W.; Gouveia, V.V.; Cameron, L.; Tankha, G.; Schmuck, P.; Franek, M. Values and their relationship to environmental concern and conservation behavior. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2005, 36, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catton, W.; Dunlap, R. Environmental sociology: A new paradigm. Am. Sociol. 1978, 13, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.E.; VanLiere, K.D. The new environmental paradigm: A proposed measuring instrument and preliminary results. J. Environ. Educ. 1978, 9, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Petegem, P.; Blieck, A. The environmental worldview of children: A cross-cultural perspective. Environ. Educ. Res. 2006, 12, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopnina, H. Evaluating education for sustainable development (ESD): Using ecocentric and anthropocentric attitudes toward the sustainable development (EAATSD) scale. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2013, 15, 607–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crist, E. On the poverty of our nomenclature. Environ. Humanit. 2013, 3, 129–147. [Google Scholar]

- Kidner, D. Why “anthropocentrism” is not anthropocentric. Dialect. Anthropol. 2014, 38, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszak, T.E.; Gomes, M.E.; Kanner, A.D. Ecopsychology: Restoring the Earth, Healing the Mind; Sierra Club Books: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Buttel, F.H.; Humphrey, C.H. Sociological theory and the natural environment. In Handbook of Environmental Sociology; Dunlap, R.E., Michelson, W., Eds.; Greenwood Press: Westport, CT, USA, 2002; pp. 33–69. [Google Scholar]

- Brandtstädter, J. Goal pursuit and goal adjustment: Self-regulation and intentional self-development in changing developmental contexts. Adv. Life Course Res. 2009, 14, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P.; Olson, B.D. Personality development: Continuity and change over the life course. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2010, 61, 517–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruner, J. Acts of Meaning; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Savickas, M.L. Career Counselling; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Holstein, J.; Gubrium, J. The Self We Live by: Narrative Identity in a Post-Modern World; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, B.; Harré, R. Positioning: The discursive production of selves. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 1990, 20, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaPointe, K. Narrating career, positioning identity: Career identity as a narrative practice. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 77, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P. The psychology of life stories. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2001, 5, 100–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stets, J.E.; Biga, C.F. Bringing identity theory into environmental sociology. Sociol. Theory 2003, 21, 398–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stets, J.E.; Burke, P.J. A sociological approach to self and identity. In Handbook of Self and Identity; Leary, M., Tangney, J., Eds.; Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 128–152. [Google Scholar]

- Devine-Wright, P.; Clayton, S. Introduction to the special issue: Place, identity and environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes-Coonroy, J.S.; Vanderbeck, R.M. Ecological identity work in higher education: Theoretical perspectives and a case study. Ethics Place Environ. 2005, 8, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomashow, M. Ecological Identity: Becoming a Reflective Environmentalist; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnett, M. Normalizing catastrophe: Sustainability and scientism. Environ. Educ. Res. 2013, 19, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L.; Flanders Cushing, D. Education for strategic environmental behavior. Environ. Educ. Res. 2007, 13, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jensen, B.B.; Schnack, K. The action competence approach in environmental education. Environ. Educ. Res. 1997, 3, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wals, A. Between knowing what is right and knowing that it is wrong to tell others what is right: On relativism, uncertainty and democracy in environmental and sustainability education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2010, 16, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed; Continuum: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Shor, I. Empowering Education: Critical Teaching for Social Change; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kopnina, H.; Gjerris, M. Are some animals more equal than others? Animal rights and deep ecology in environmental education. Can. J. Environ. Educ. 2015, 20, 109–123. [Google Scholar]

- Kopnina, H. Neoliberalism, pluralism, environment and education for sustainability: The call for radical re-orientation. Environ. Dev. 2015, 15, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, J.T. Weapons of Mass Instruction; New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, BC, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, J. How Children Fail, revised ed.; Perseus Books: Reading, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hermans, H.J.M.; Hermans-Konopka, A. Dialogical Self Theory. Positioning and Counter-Positioning in a Globalizing Society; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson, G. Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C. On Organizational Learning, 2nd ed.; Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Meijers, F.; Lengelle, R. Narratives at work: The development of career identity. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2012, 40, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, W.F. Learning: A Survey of Psychological Interpretations; Thomas, Y., Ed.; Crowell: Oxford, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Schunk, D.H. Learning Theories: An Educational Perspective; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cobham, T.E. Ethics Education of Business Leaders: Emotional Intelligence, Virtues, and Contemplative Learning (Transforming Education for the Future); Information Age Publishing: Charlot, NC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Huckle, J. Towards greater realism in learning for sustainability. In Learning for Sustainability in Times of Accelerating Change; Wals, A.J., Corcoran, P.N., Eds.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson, J.; van der Linden, S.; Chabay, I. The role of knowledge, learning and mental models in public perceptions of climate change related risks. In Learning for Sustainability in Times of Accelerating Change; Wals, A.J., Corcoran, P.N., Eds.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 329–346. [Google Scholar]

- Shao-Chang, W.B. On agendas and perspectives in environmental education: Revisiting Kopnina, disciplinary imperatives and the paradoxes of (multi)cultures. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 19, 266–288. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science 1974, 185, 1124–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; Farrar, Strauss & Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H.A. A behavioural model of rational choice. Q. J. Econ. 1955, 69, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieshok, T.S.; Black, M.D.; McKay, R.A. Career decision making: The limits of rationality and the abundance of non-conscious processes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 76, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijksterhuis, A.; Nordgren, L.F. A theory of unconscious thought. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 2, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijksterhuis, A.; Bos, M.W.; Nordgren, L.F.; van Baaren, R.B. On making the right choice. The deliberation-without-attention-effect. Science 2006, 311, 1005–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, T.D.; Schooler, J.W. Thinking too much: Introspection can reduce the quality of preferences and decisions. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 60, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damasio, A. The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion and the Making of Consciousness; Heinemann: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stuss, D.T.; Anderson, V. The frontal lobes and theory of mind: Developmental concepts from adult focal lesion research. Brain Cognit. 2003, 55, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, B. The Paradox of Choice; Harper Perennial: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.C. The focal theory of adolescence: A psychological perspective. In The Social World of Adolescents; International Perspectives; Hurrelmann, K., Engel, U., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 1989; pp. 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, G.A. Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Choices, Values, and Frames; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopnina, H. Education for sustainable development (ESD): The turn away from “environment” in environmental education? Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 699–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, S.C.; van Dijk, E.E. Transformative learning: Towards the social imaginary of sustainability: Learning from indigenous cultures of the American continent. In Learning for Sustainability in Times of Accelerating Change; Wals, A.J., Corcoran, P.N., Eds.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 225–240. [Google Scholar]

- Kegan, R. Over Our Heads: The Mental Demands of Modern Life; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kegan, R.; Broderick, M.; Drago-Severson, E.; Helsing, D.; Portnow, K. Toward a New Pluralism in ABE/ESOL Classroom: Teaching to Multiple “Cultures Of Mind”; Executive Summary NCSALL Report #19a; Harvard University Graduate School of Education: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin, A. Educative research, voice, and school change. Harv. Educ. Rev. 1990, 60, 443–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E. Identity: Youth and Crisis; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bühler, C. From Birth to Maturity; Kegan Paul, Trench & Trubner: London, UK, 1935. [Google Scholar]

- Bühler, C.; Allen, M. Introduction to Humanistic Psychology; Brooks/Cole Publishing: Monterey, CA, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Frijda, N. The Emotions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, J.J.; Sheppes, G.; Urry, H.L. Emotion generation and emotion regulation: A distinction we should make (carefully). Cognit. Emot. 2011, 25, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Woerkom, M. Critical reflection as a rationalistic ideal. Adult Educ. Q. 2010, 60, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendlin, E.T. Focusing, 2nd ed.; Everest House: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Gendlin, E.T. Focusing-Oriented Psychotherapy; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer, R.A. Fostering post-traumatic growth: A narrative contribution. J. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lehr, U. Das mittlere Erwachsenenalter; ein vernachlässigtes Gebiet der Entwicklungs-psychologie. In Entwiclung als Lebenslanger Prozess; Oerter, R., Ed.; Hoffmann & Campe: Hamburg, Germany, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. A critical theory of self-directed learning. In Self-Directed Learning: From Theory to Practice; Brookfield, S., Ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hermans, H.; Kempen, H. The Dialogical Self-Meaning as Movement; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hermans, H.J.M.; Kempen, H.J.G.; van Loon, R.J.P. The dialogical self: Beyond individualism and rationalism. Am. Psychol. 1992, 47, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, D. The Secret History of Emotion: From Aristotle’s Rhetoric to Modern Brain Science; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cavico, F.J.; Muffler, S.C.; Mujtaba, B.G. Appearance discrimination, “lookism” and “lookphobia” in the workplace. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2012, 28, 791–802. [Google Scholar]

- Chartrand, T.L.; Bargh, J.A. The chameleon effect: The perception-behavior link and social interaction. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 893–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, D.W. Black women can’t have blonde hair… in the workplace. J. Gend. Race Justice 2011, 14, 405–431. [Google Scholar]

- Howlett, N.; Pine, K.J.; Cahill, N.; Orakcioglu, I.; Fletcher, B. Unbuttoned: The interaction between provocativeness of female work attire and occupational status. Sex Roles 2015, 72, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hofstadter, D.R. Analogy as the Core of Cognition; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- McGilchrist, I. The Master and His Emissary; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wilentz, G. Healing Narratives: Women Writers Curing Cultural Dis-Ease; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, M.B. The social self: On being the same and different at the same time. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 17, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardelli, G.J.; Pickett, C.L.; Brewer, M.B. Optimal distinctiveness theory: A framework for social identity, social cognition, and intergroup relations. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 43, 63–113. [Google Scholar]

- Polkinghorne, D.E. Narrative Knowing and the Human Sciences; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, H.P. The Cambridge Introduction to Narrative; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Beattie, O. Life themes: A theoretical and empirical exploration of their origins and effects. J. Humanist. Psychol. 1979, 19, 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Kopnina, H. The Lorax complex: Deep ecology, ecocentrism and exclusion. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2012, 9, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, I.H. The Winner Effect. The Neuroscience of Success and Failure; St. Martin’s Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, M.; Clandinin, J. Stories of experience and narrative inquiry. Educ. Res. 1990, 19, 174–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinar, W. Currere: Toward reconceptualization. In Basic Problems in Modern Education; Jelinek, J., Ed.; Arizona State University, College of Education: Tempe, AZ, USA, 1974; pp. 147–171. [Google Scholar]

- Doerr, M. Currere and the Environmental Autobiography: A Phenomenological Approach to the Teaching of Ecology; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lengelle, R.; Meijers, F.; Poell, R.; Post, M. The effects of creative, expressive, and reflective writing in career learning. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 83, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengelle, R.; Meijers, F.; Poell, R.; Post, M. Career writing: Creative, expressive, and reflective approaches to narrative identity formation in students in higher education. J. Vocat. Behav. 2014, 85, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanu, Y.; Glor, M. “Currere” to the rescue? Teachers as “amateur intellectuals” in a knowledge society. J. Can. Assoc. Curric. Stud. 2006, 4, 101–122. [Google Scholar]

- Winters, A.; Meijers, F.; Lengelle, R.; Baert, H. The self in career learning: An evolving dialogue. In Handbook of Dialogical Self Theory; Hermans, H.J.M., Gieser, T., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 454–469. [Google Scholar]

- Law, B. A career learning theory. In Rethinking Careers Education and Guidance; Theory, Policy and Practice; Watts, A.G., Law, B., Killeen, J., Kidd, J., Hawthorn, R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1996; pp. 46–72. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Chun, M.N. Selective attention modulates implicit learning. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2001, 54A, 1105–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reber, P.J.; Gitelman, D.R.; Parrish, T.B.; Mesulam, M.M. Dissociating explicit and implicit category knowledge with fMRI. J. Cognit. Neurosci. 2003, 15, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochran, L. Career Counseling: A Narrative Approach; Sage: Thousand Oakes, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Baer, R.A. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 10, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, D. Educating the Reflective Practitioner; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Finke, R.A. Creative insight and pre-inventive forms. In The Nature of Insight; Sternberg, R.J., Davidson, J.E., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994; pp. 255–280. [Google Scholar]

- Black, M. More about metaphor. In Metaphor and Thought, 2nd ed.; Ortony, A., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993; pp. 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kearney, K.S.; Hyle, A.E. Drawing out emotions: The use of participant-produced drawings in qualitative inquiry. Qual. Res. 2004, 4, 361–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitch, R. Limitations of language: Developing arts-based creative narrative in stories of teachers’ identities. Teach. Teach. 2006, 12, 549–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Väliverronen, E. Biodiversity and the power of metaphor in environmental discourse. Sci. Stud. 1998, 11, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Van Loon, R. Symbolen in het Zelfverhaal. Een Interpretatiemodel met behulp van de Zelfkonfrontatiemethode (Symbols in the Story about the Self; an Interpretative Model Using the Self-Confrontation Method); Van Gorcum: Assen, The Netherlands, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Law, B. A Career-learning Theory. Available online: http://www.hihohiho.com/newthinking/crlrnoriginal.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2010).

- Winters, A.; Meijers, F.; Kuijpers, M.; Baert, H. What are vocational training conversations about? Analysis of vocational training conversations in Dutch vocational education from a career learning perspective. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2009, 61, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doorewaard, H. De andere Organisatie… en Wat Heeft de Liefde er Nou mee te Maken? (The other Organisation… and What Has Love Got to Do with It?); Lemma: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Humphrey, R.H. Emotion in the workplace: A reappraisal. J. Manag. 1995, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, A. Philosophy: Who Needs It; Signet: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, D.; Stauth, C. What Happy People Know; St. Martin’s Griffin: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker, J. The Secret Life of Pronouns; Bloomsbury Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kuijpers, M.; Meijers, F. Professionalising teachers in career dialogue: An effect study. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlaar-Oostveen, M.; Meijers, F. Zijn stagegesprekken in het hbo reflectief en dialogisch? (Are career conversations in higher education reflective and dialogical?). Tijdschr. Voor Hoger Onderwijs 2014, 32, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobern, W.W.; Loving, C.C. Defining “science” in a multicultural world: Implications for science education. Sci. Educ. 2001, 85, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franciosi, R.J. The Rise and Fall of American Public Schools: The Political Economy of Public Education in the Twentieth Century; Praeger: Westport, CT, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, S.L.; Berliner, D.C. Collateral Damage: How High Stakes Testing Corrupts America’s Schools; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, A. Teaching in the Knowledge Society: Education in the Age of Insecurity; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Louv, R. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder; Workman Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meijers, F.; Lengelle, R.; Kopnina, H. Environmental Identity and Natural Resources: A Dialogical Learning Process. Resources 2016, 5, 11. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/resources5010011

Meijers F, Lengelle R, Kopnina H. Environmental Identity and Natural Resources: A Dialogical Learning Process. Resources. 2016; 5(1):11. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/resources5010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeijers, Frans, Reinekke Lengelle, and Helen Kopnina. 2016. "Environmental Identity and Natural Resources: A Dialogical Learning Process" Resources 5, no. 1: 11. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/resources5010011