‘We all design when we plan for something new to happen, whether that might be a new version of a recipe, a new arrangement of the living room furniture … The evidence from different cultures around the world, and from designs created by children as well as by adults, suggests that everyone is capable of designing. Therefore, Design Thinking is something inherent within human cognition: it is a key part of what makes us human.’

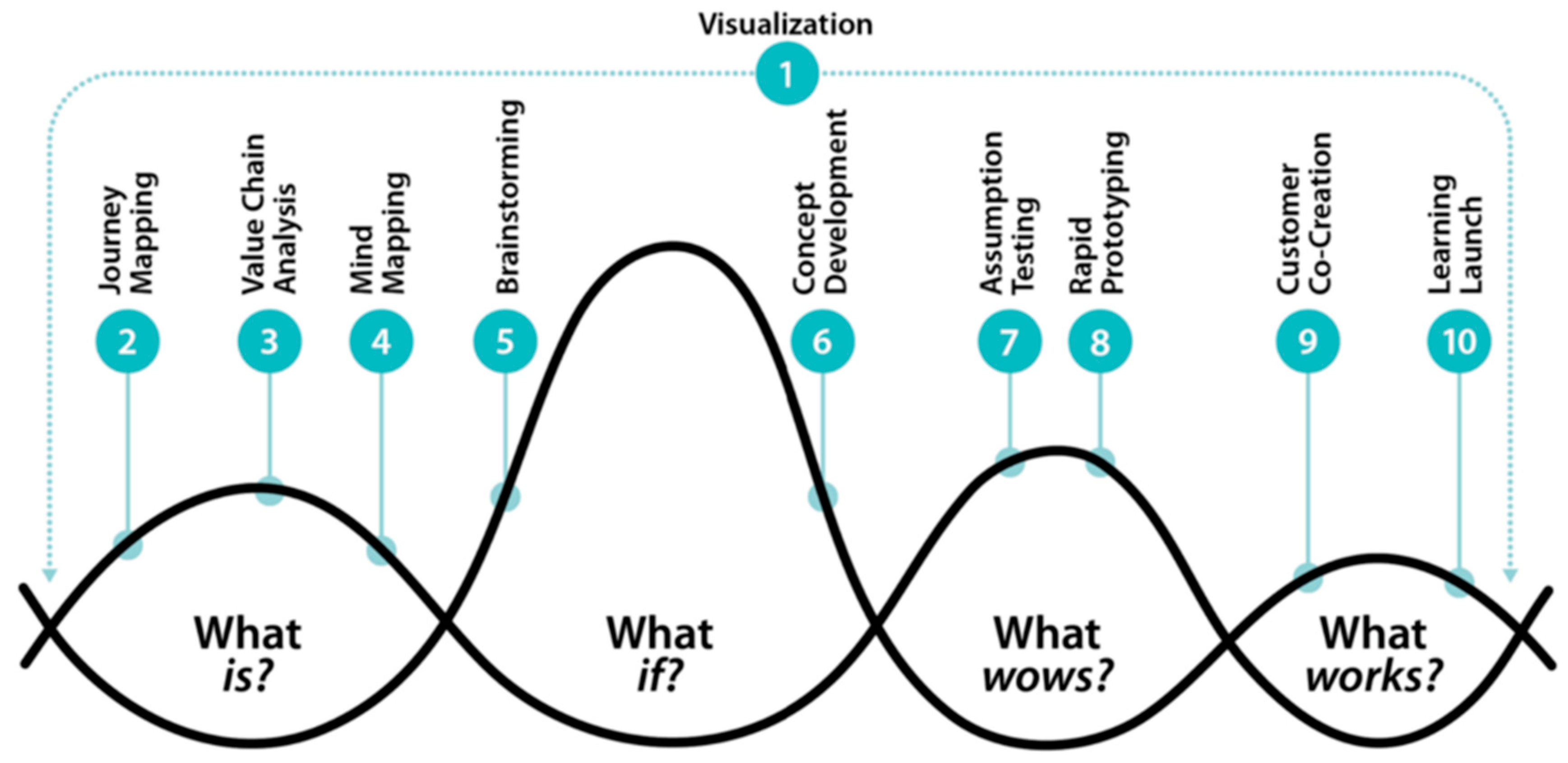

Academics and practitioners alike now coalesce around broad definitions of Design Thinking that see it as a creative, iterative, hypothesis-driven process that is focused on both the problem and the solution. Relying on abduction and experimentation, it balances the twin drivers of possibility and constraint and works best in situations of high complexity, ambiguity and uncertainty (in other words, VUCA environments). It has to navigate between customer wants and needs, client expectations, social circumstances, business models, opportunities in technology and contemporary aesthetic canons.

3.1. The Way Designers Think

Davies and Talbot [

36], in a series of interviews with designers, trying to understand what made them more creative than other professions, discovered that they rely heavily on

intuition for their ideas. One of the interviewees, Jack Howe, an architect and designer, said ‘I believe in intuition. I think that is the difference between a designer and an engineer’ [

37]. Today, a similar observation can be made about the difference between data-scientists and design thinkers. The latter use abductive thinking or intuition while the former rely exclusively on data. Cross [

21] suggests that the term intuition is really a convenient shorthand for what really happens in Design Thinking which —as opposed to inductive or deductive thinking—is abductive thinking. Deductive reasoning is the reasoning of formal logic. It begins with a hypothesis, perhaps one such as: all swans are white. Then, some fieldwork is designed to either prove or falsify that hypothesis. This is the dominant orthodoxy for business analysis. This is the bread and butter of all MBA-trained executives. Inductive reasoning, however, aims to build theory from data. Hence, it does not begin with any firm hypothesis; it begins by observing how things actually are and then it builds theory accordingly. This is generally used in more qualitative contexts, where the variable being studied is highly context-dependent, like corporate innovation—how firms come up with winning ideas, for instance. Abductive reasoning is a blend of the two types that employs intuition to stimulate divergent thinking and, ultimately to arrive at more original ideas (see

Box 1).

Quantitative, big data analytics are now synonymous with the digital business environment, but prevalent use of data mining methods rely exclusively on observations about past behaviour and are not necessarily a reliable guide to the future [

7]. To thrive in the VUCA environment, businesses are increasingly turning to more sophisticated and sensitive frameworks and structures to allow them sense attractive market opportunities and seize them as they move more sharply into view [

38].

Cross [

21] offers a fascinating vignette in an attempt to deconstruct designers do. The case he describes is Philippe Starck’s iconic design for a lemon squeezer. In the late 1980s, Philippe Starck was already a celebrated designer of a wide range of different products. He was approached at that time by Alessi. The Alessi company had begun to develop a new series of homeware or kitchen products designed by famous designers, including kettles and coffee pots by architects Michael Graves and Aldo Rossi and cutlery and condiment sets by industrial designers Ettore Sottsass and Roger Sapper. They invited Starck to contribute to this prestigious series of new products and they suggested that he work on designing a lemon squeezer. The story goes that Starck come to Alessi, outside Milan, to discuss the project and, following the meeting, took a short vacation on the small island of Capraia, just off the Tuscan coast.

While there, he dined in a pizza restaurant, called Il Corsaro (translated as the buccaneer or pirate). He mused over the lemon squeezer project as he waited for his food to arrive—he had ordered the squid. He began to sketch on the placemat in the restaurant and his first iterations (in the centre to the right of

Figure 2) reflected conventional squeezer designs; see

Figure 2. However, as his food arrived, something else was triggered in his imagination and he began to create images of strange forms with big bodies and long legs. Ultimately, in the bottom left of the placemat, he arrived at the blueprint for what was to become one of the iconic designs of the 20th century.

Lloyd and Snelders [

39], in describing the probable creative trajectory for this great design, suggest that the squid-like concept was not a sudden flash of inspiration from out of the blue but that it arose from a form of analogy that probably began unconsciously but gradually became more deliberate. It is the intersection of three forms of parallel thought. The first is the problem of how to squeeze a lemon, the second involves creatively mining the possibilities offered by the shape of the squid and the third draws on Starck’s interest and liking for science-fiction comic books in his youth and the unmistakable resemblance to some shapes, possibly from HG Wells’ War of the Worlds.

However, as Design Thinking becomes more widespread, so its limitations become more evident. One such limitation is that inherent in Design Thinking is its user-centric approach. It places users in the centre of the process and gives them the dominant voice in the innovation dialogue. While customers are the necessary ingredient for any successful business, they are rarely gifted with imagination or penetrating insights about the future. They cannot anticipate unmet or unarticulated needs and they are rarely the source for radical ideas. Design Thinking tends to anchor innovators in the incremental and hence, while it is a great set of tools for businesses, it can constrain breakthrough thinking.

Another shortcoming concerns Design Thinking’s core discipline being design. However, design has historically concerned itself with the design of objects, artefacts, products—physical things [

40]. Famous designers are generally famous for designing in specific physical domains: Frank Gehry designed wonderful buildings; Coco Chanel designed beautiful clothes; Jonny Ive designed breathtaking phones and computers; Paul Rand designed memorable logos, while Ray and Charles Eames designed stylish furniture. Hence, as design expands its operating remit into services, into experiences and even into strategy another problem can emerge. Brown and Martin [

40] note that when designers take a brief, an issue or a business opportunity and go away to work their magic on the problem at hand, inevitably they return to the boardroom with their proposed solution and when they do, one of four things often happen. This scenario increases in likelihood with the degree of difference between the designer’s proposal and the current operating model. The more the proposal deviates from the business-as-usual scenario, the more likely executives are to have this reaction: ‘(1) This does not address the problems I think are critical. (2) These aren’t the possibilities I would have considered. (3) These aren’t the things I would have studied. (4) This is not an answer that is compelling to me’ (Ibid.). As a consequence, winning commitment to the strategy tends to be the exception rather than the rule, especially when the strategy represents a meaningful deviation from the status quo ‘. Fortunately, the toolbox of Design Thinking has an approach to manage this disconnect. Instead of making the proposed change look like a small number of big steps, they do the opposite and by iteration and low-res prototypes, they make the change seem like a logical sequence of lots of small, incremental steps.

In framing the relevance of this case study, it’s worth noting that Design Thinking’s association with the tourism and arts sector is already established; cases include the future of hotels [

41], Indian artisanship [

42], a cultural cluster in Dublin [

43], and a wine region in Spain [

44].

The Beginnings of an Art Thinking Movement

Whitaker [

2] notes that Art Thinking shares several similarities with Design Thinking. They both provide a framework and tools for facilitating the design of a new product or service. An important distinction she draws is that ‘whereas a framework originating in product design starts with an external brief—‘What is the best way to do this?’—Art Thinking emanates from the core of the individual and asks, ‘Is this even possible?’’ Art Thinking spends much more time in the problem space: it is not customer-centred; it is breakthrough-oriented.

Coles [

45] notes that there has always been a rift between art and design in our culture. He notes that purists on both sides are keen to maintain their disciplinary differences, while others believe that design is a suitable bedfellow for art and that art should be more ‘gregarious’ and reach out beyond its confines. Some see design merely as decorating art for human use and hence any such ‘decoration’ is undesirable. However, as early as 1859, Rushkin, showing little sympathy with this argument, insisted that:

There is no existing higher order for art that is decorative. The best sculpture yet produced has been the decoration of a temple front—the best painting, the decoration of a room. Get rid, then, at once of any idea of Decorative art being a degraded or separate kind of art.

In his series of essays, The Shape of Things [

46], the first essay is entirely devoted to the origin of the word ‘design’. It stems from the Latin word signum meaning ‘sign’. Thus, etymologically, design means to ‘de-sign’. So far from adding unnecessary decoration, it entails the removal of something: a simplification. In the same essay, Flusser went on to elaborate on other words often used in the same context—such as technology. The Greek word techne actually means ‘art’ and is a first cousin of ‘tecton’, a carpenter. The basic idea here is that wood is a shapeless material to which the artist, the technician, the carpenter gives some design and form.

Therefore, in derivation and etymology, the words technology, art and design are very closely related. However, what Coles [

45] calls ‘modern bourgeois culture of the mid-nineteenth century’ has created a very sharp distinction between the world of art and that of technology. This has split the culture and practice into two mutually exclusive branches: one scientific, data-driven and ‘hard’ and the other intuitive, aesthetic and ‘soft’. This unfortunate split became irreversible with the rise the machine bureaucracy organisation [

47]. Yet, the only discipline capable of bridging these two disparate worlds and of integrating them is design. In Flusser’s [

46] view, design indicates the sweet spot where art and technology meet to produce new forms of culture, and so the role of design is crucial to the vitality of the arts and similarly, the role of art is at the very heart of design.

Science and art are separate realms where one prizes data and the other aesthetics: it has long been noted that gifted practitioners of the former and very often equally talented at the latter. Metz [

48] notes that Einstein played both the piano and violin: Max Planck composed songs and even a full opera. He also played the piano, organ and cello. Roald Hoffmann, the Polish-American theoretical chemist who won the 1981 Nobel Prize in Chemistry also published plays and poetry. Nobel Prize winner in 1906, Santiago Ramón y Cajal was a celebrated photographer and artist. Pomeroy’s research (2012) suggests that Nobel laureates in the sciences are 17 times more likely than (the average scientist) to be a painter, 12 times more likely to write poetry, and four times more likely to be a musician. Students of Leonardo Da Vinci or Albrecht Dürer will not be surprised at this, as they were also scientists, as well as being consummate artists. The link is thus long-established.

There is another dichotomy at work here, too, and that is the division between strategy and creativity. Bilton and Cummings [

49] assert that this, too, is a false dichotomy. Business leaders often equate creativity (sometimes disparagingly) with novelty, spontaneity, like an unplanned eruption of new and often random ideas. They see ‘creativity as unfettered, dynamic, borderline-crazy right-brain thinking’ (p. 5). While strategy, on the other hand, is rational; it is solid, it is about systems, control and accountability. On both sides, creativity and strategy are seen as extraordinary opposites of one another rather than as integral to each other. For a strategy to be successful, it has to have an element of creativity within it—otherwise it would be a predictable, paint-by-numbers plan which would not offer any competitive advantage. In addition, for creativity to take root, for an idea to spread, it too needs to be framed strategically, rationally, otherwise it would just pop, fizz and evaporate. Arthur Koestler [

50] similarly concludes that invention or discovery takes place through the combination of different ideas and angles. He notes that the Latin verb ‘

cogito’, to think, actually means to ‘shake together’ which is the creative act of making connections between previously unrelated things. In the business world, this is known as ‘kaleidoscope thinking’: the shaking together of known elements into previously unconsidered combinations [

51].

Fresh perspective to this debate was brought when business and management guru, Daniel Pink said in a New York Times interview that the ‘Now the Master of Fine Arts, or MFA is the new MBA’. Pink sees that much of the work of analytics and mathematics that is central to business can now be done better and more easily by computers and it is now time, given that we now compete in a creative economy, to allow the right brain take centre stage. Pink later converted this assertion into an HBR article [

52] in which he explained the reasons for the rise in demand for creative people coupled with the oversupply with people with MBAs explains why the MFA is now the ‘hottest credential’ in the world of business.

Amy Whitaker’s [

2] book entitled

Art Thinking is the first substantial effort to flesh out the notion of Art Thinking. In it, she has some practical insights. She describes the root of the concept to be Schumpeterian, insofar as capitalism is entirely predicated on change and the need for disruption and reinvention to stimulate business growth. Schumpeter asserted that if firms keep doing the same thing, eventually they go out of business. ‘Following patterns rather than inventing new ones will only get you so far.’

Progress for any organisation demands that it be able to refresh its portfolio of market offerings, allowing the old products and services give way to its new innovations. Schumpeter [

53] referred to this as creative destruction, where new ideas capsize and replace the old ones. Drucker [

54] supported this paradigm when he said that ‘innovation depends on organised abandonment’. Art Thinking is for companies seeking this type of growth, possibly even transformational growth. ‘They can grow by scaling up to the most efficient level of production. Or they can grow artistically by the alchemy of invention.’ Whitaker [

2] recognises that this can be challenging for business because:

‘Business prizes being able to put prices on things and to know their value ahead of time. Yet, if you are inventing Point B, in any area of life—you can’t know the outcome at the moment you have to invest money, time and effort in the Point A world. This is the central paradox of business: the core assumptions of economics—efficiency, productivity and knowable value—work best when an organisation is at cruising altitude, but they will not get the plane off the ground in the first place.’

(p. 8)

While Whitaker’s emerging theory of Art Thinking has yet to be empirically tested, there is one mention of it in the literature: a 2016 conference presentation about the car brand Mazda [

55] in which the authors assert that Mazda believe ‘the car is art.’ They underpin this contention, from interviews with 5 Mazda designers, by explaining that these artists try to express their emotions and beliefs in car design. They would not compromise themselves by pandering explicitly to customer needs. In doing this, they go beyond Design Thinking, which ‘tries to meet specific customer needs’, and they enter the realm of car design motivated by Art Thinking.

3.3. Details of the Case Study

Strategic initiatives in the Arts include bringing in strategic frameworks or strategic management or generally importing approaches from the business world, often at the behest of senior managers, of government funders or other stakeholders like Board directors. Hence, ‘strategy’ in the arts is usually resented as something that is imposed from outside and something that needs to be tolerated temporarily till the recession or existential crisis recedes and the organisations get back on their feet.

The story of the recent history of Graphic Studio Dublin is the story of a highly creative strategy being applied to an Arts organisation with profound and positive effects; a story of how strategy rescued a national arts organisation from the brink of closure and ruin and restored its place in the visual arts ecosystem as well as restoring its fortunes. What makes it exceptional and, therefore, revelatory, is that it deals with an organisation going through a crisis. However, in order to tell the story, like all good research subjects, it needs a little context. This context requires a visit to 1960s Dublin. Ireland in the mid-twentieth century was delicately balanced between an economic isolationism imposed both by the end of the second world war and by a political leader who favoured self-sufficiency and protectionism, which turned into the twin drivers of economic stagnation for almost a decade. On the other hand, and despite the economic stasis, the arts were seeing an expansion; a cultural revival.

Several notable, even defining cultural initiatives took place in Ireland at this time in both public and private spheres: the establishment of the Wexford Opera Festival, the Dolmen Press, the Arts Council, the Dublin Theatre Festival, and the Irish Georgian Society. In terms of policy, too, there was the launch of TK Whitaker’s 1958 Economic Development Plan (which was Ireland’s blueprint out of self-imposed economic atrophy), the launch of Ireland’s first national television broadcasting service called Telefis Eireann, the publication of Design in Ireland by the Scandinavian Design Group, and the opening of the Kilkenny Design Workshops in 1965. Ireland was also opening up to international cultural influences. During the 1960s, the Beatles performed in Dublin, as did Ella FitzGerald, The Rolling Stones, Oscar Peterson, Cliff Richard, Louis Armstrong and Bing Crosby.

One other remarkable development in Ireland occurred at this time: Shannon, the first new town founded in Ireland since the 17th century, was established in 1963 and was based not around a harbour or a fortress, nor a market (as all towns had been since Medieval times). Rather, it was located at an airport. Shannon and the other institutions mentioned were all responding to significant gaps in the cultural, educational and economic landscape in Ireland at that time.

However, while there was considerable change, the air was also heavy with continuity, certainly in the Arts. The fact that the Arts Council had been overseen for over a decade by two priests in succession, Monsignor Padraig de Brún (1959–1960) and Father Donal O’Sullivan (1960–1973), now seems remarkable. There were nine board members of the Arts Council, and all were male, and as the leadership was coming from the most conservative pillar of Irish society, the Church, it is hard to imagine anything but the most conservative projects and initiatives getting financial support.

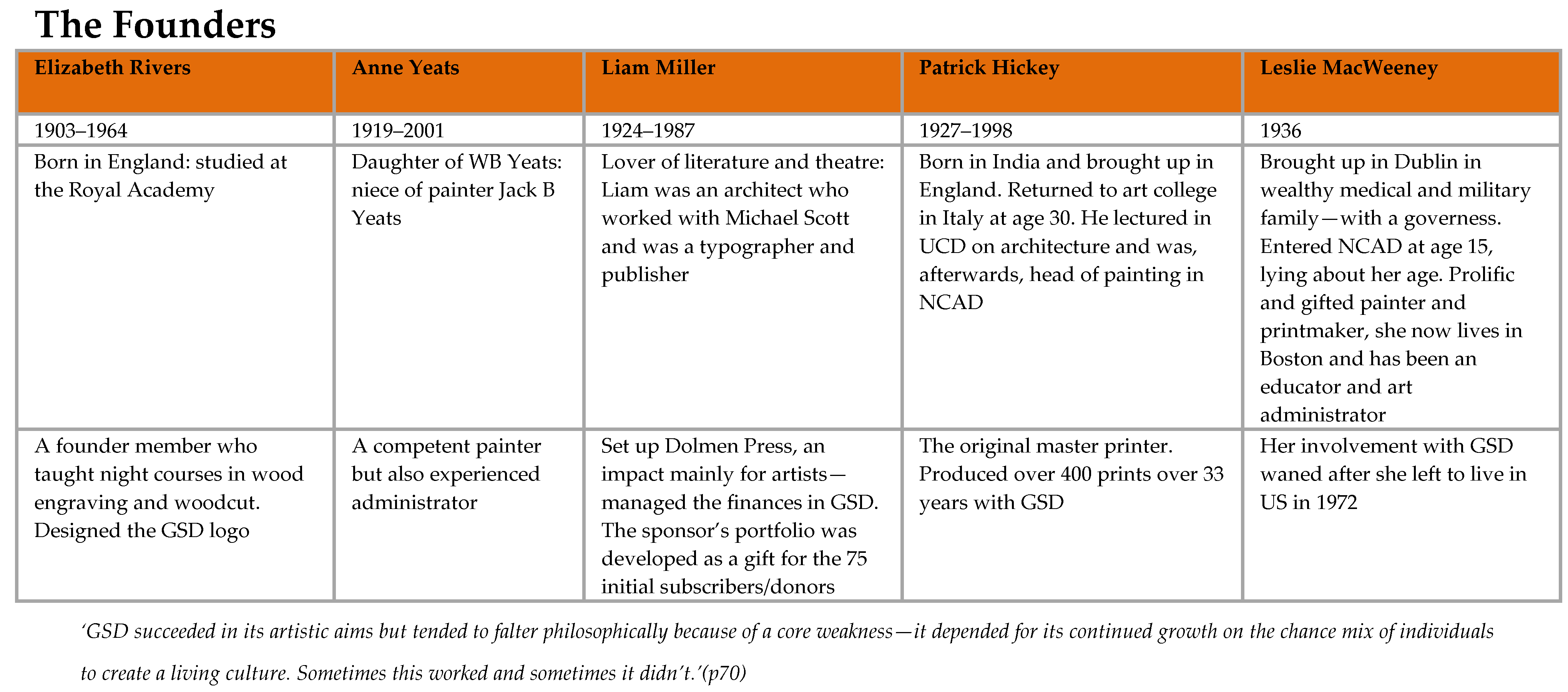

It was against this backdrop that in Ireland’s cultural district, often called ‘Baggotonia’—the Georgian streets around Merrion Square and Baggot Street- that Graphic Studio Dublin (GSD) was founded. It was created, by an eclectic set of founders (see

Figure 3), for artists and it was led by artists. GSD was Ireland’s first fine art print studio and for its first three decades, it struggled to survive, sustained only by idealism and a grim determination to provide shared facilities so that talented artists could make important art. The chronicler of the organisation, Brian Lalor, in his book, Ink Stained Hands [

59] makes an insightful observation about the early years:

Ink Stained Hands is the story of this triumph—over the absence of an informed critical climate and the absence of a marketplace, over infighting, personal antagonisms and feuds, over ideological differences and intransigence disguised as high principle and through a web of official misunderstanding—it emerged half a century later, invigorated with idealism and optimism intact and a lengthy inventory of artistic achievement to its credit.

(p. XXIII)

The founders of the Graphic Studio were a group of five well-intentioned, hugely talented and diverse characters, each with a distinct and established profile in the arts. Their backgrounds spanned education, publishing, architecture, literary criticism and painting and printmaking. See

Figure 3:

Printmaking was also enjoying a resurgence in North America, in Britain, France, Russia and Scandinavia and many new print studios were being set up, often with the assistance of generous philanthropic donations. Hence GSD can be seen as part of a more widespread pattern on international development in fine-art printmaking. Many of the world’s leading print studios were set up around this time. In the US: Pratt Contemporary Graphic Art Centre (1956), Tamarind Lithography Workshop (1960), Crown Point Press (1962) and Hollanders Workshop (1964). England saw the establishment of the Curwen Press (1958) and Scotland, Edinburgh Printmakers (1967). The seed funding of these various establishments tells its own story. In the US, big businesses were more established, and the germs of the concept destined to become corporate social responsibility were already visibly benefiting the arts. Pratt-Contemporaries received a donation of

$50,000 from the Rockefeller family, while Tamarind received

$135,000 from the Ford Motor Corporation.

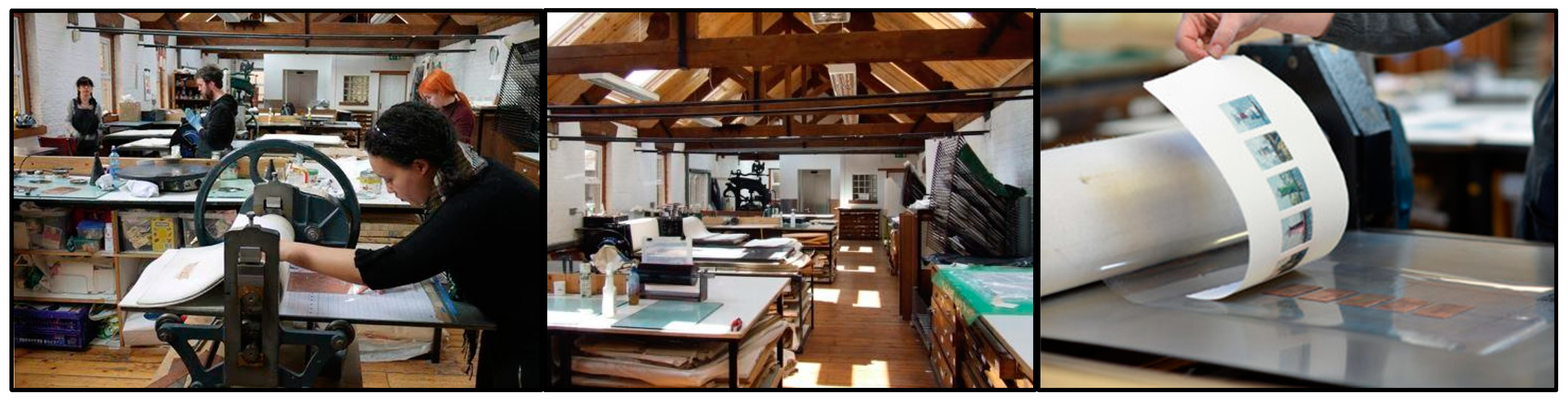

Figure 4 shows some of the printmaking techniques used in GSD.

However, raising money, especially for the Arts, in the cash-strapped Ireland of the 1960s, was a far trickier proposition. The Irish Export Board came forward with £120 and, while this was derisory when compared to US funding, in Ireland’s low-wage and even lower-expectation economy, it was able to go a long way. However, one of the early successes of GSD was an imaginative business model they developed through which generous individual sponsors were encouraged to make a modest annual contribution in return for which they would receive as a gift a small portfolio of prints. This ‘sponsors’ portfolio’ idea still persists to this day, some 50 years later. GSD became a thriving, successful, dynamic artistic community recognised by the Arts Council as part of the visual arts landscape in Ireland and recognised by artists as a commune where inexperienced and veteran printmakers; where master and pupil could work side by side.

Fast-forward, then, almost 50 years later. In 2007, experiencing growing pains and needing additional space to accommodate new equipment and to offer new, emerging printmaking techniques such as silk-screen, GSD now had its own CEO, its own Studio Director (a master-printmaker) and it had acquired its own gallery as a sales channel for artist members to both exhibit and sell their work. It decided to purchase new premises (see

Figure 5) during the property boom in Ireland: a four-storey former granary close to the heart of the city on the northside of Dublin. To make the purchase, the organisation borrowed heavily. It had not owned premises before this one, it had been renting for the first 50 years, and the Board thought it was time to get a place they could consider home and call their own.

While the idea might have been laudable, the timing was catastrophic. It coincided with Ireland’s first ever property ‘bust’, where property prices went into freefall, precipitating the deepest and longest recession in Ireland’s history. The value of the property plummeted and the Board of GSD managed to negotiate a temporary ‘interest only’ payment arrangement on the property mortgage. However, the bank that owned the mortgage quickly sold it to a hard-nosed US vulture-fund who wanted to foreclose on the premises and to cast the artists out on the street. This would have left a generation of Irish printmakers without a place to work and without the facilities to make their art. The problems with the unsustainable mortgage were compounded by the fact that art purchases are among the first discretionary spends to get cut during a recession. People buy less art when their earnings are reduced, and hence, just when the organisation needed to show healthier revenues, its sales were drying up. This is where the VUCA environment loomed threateningly over the enterprise, with few reasons for optimism and every avenue for revenue generation apparently drying up.

Innovation in cultural organisations is considered generally to fall into one of four broad typologies [

60,

61]:

- (1)

Marketing Communications (i.e., the use of digital strategies, specifically targeting key segments more directly with better, sharper, more personalised propositions).

- (2)

Delivering the cultural experience in different or unconventional venues—like Shakespeare in Kew Gardens, for instance, or theatre in high street pubs.

- (3)

New Cultural Content—perhaps adding comedy with art or blending two or more art forms and extending both into a new realm.

- (4)

Operational Excellence—using conventional management practices and applying them to running the arts organisation and/or its events.

However, sometimes, these conventional approaches to innovation are unlikely to deliver the sort of turnaround performance that was needed in this VUCA environment.

A new Board of directors was empanelled in GSD to take up this daunting challenge and this is where the Art Thinking strategy took root. To save costs, the services of the CEO were dispensed with. The Board has nine members, of which the majority (5) are artists and the rest are volunteers, generally those interested in Art from the professions. In this instance, there is a chairman, a director of marketing and strategy (the author), a head of Legal (a bank property lawyer), and a head of finance (a chartered accountant in a large practice). The challenge for the new board was to restore GSD’s finances to the extent to which it could afford to service the full payments on a mortgage—a reduced mortgage from the one originally taken out. This meant not only getting the business back into a healthier shape, it also required that the mortgage be renegotiated with, ideally, some debt forgiveness.

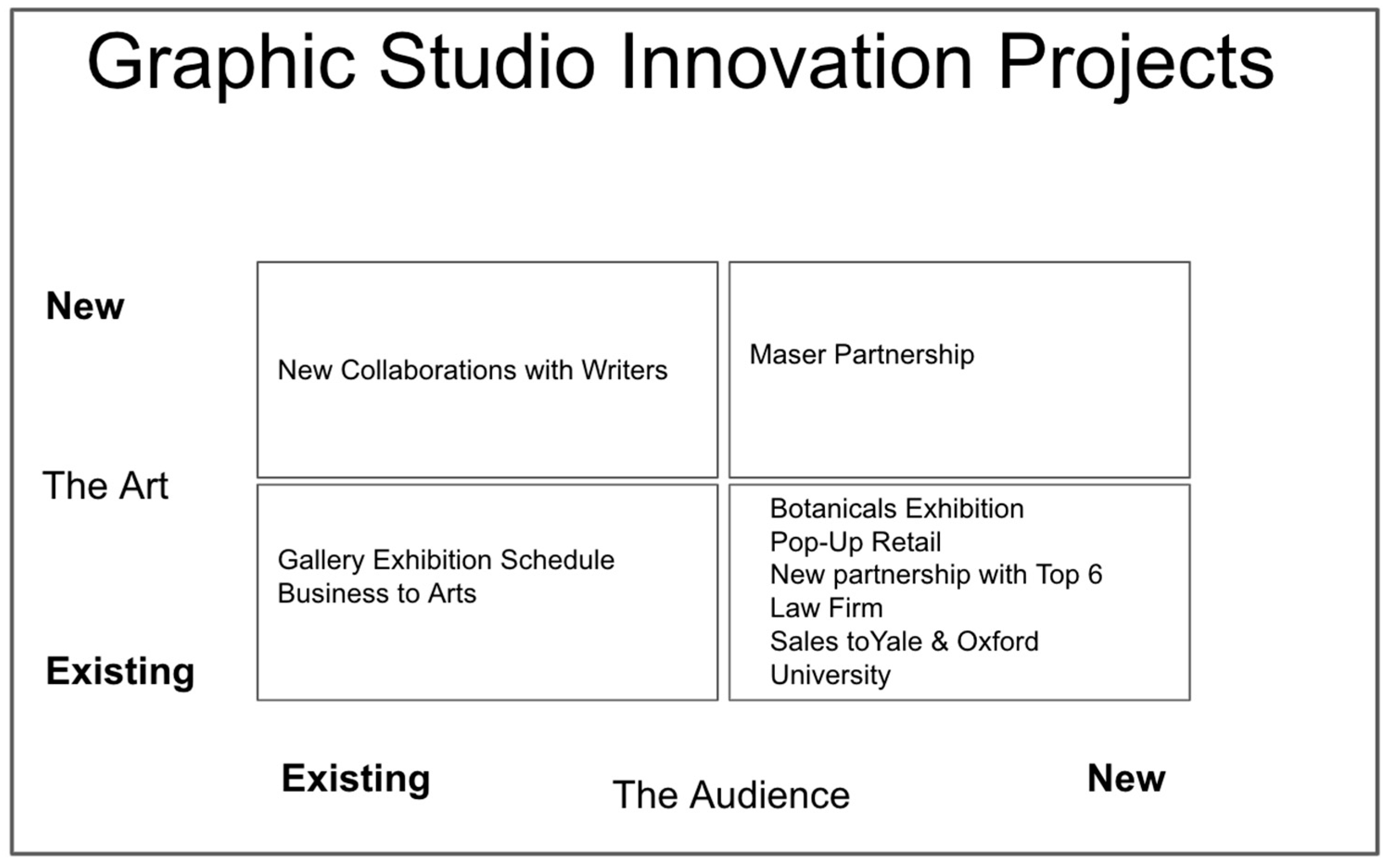

The situation was so dire that the Board really had to embrace the principles of Art Thinking: it did not seem to them as if it would be enough to plot a route from current position A to an incrementally better position of A+. The Board just had to start with inventing a vision of what a desirable point B might look like in terms of revenues, audience numbers and costs. The Board decided to get all the artists on board to co-create a new, commercial strategy to pull the organisation back from the edge. Several artists (roughly 12) attended a Strategy Day in which a strategic North Star and set of guiding principles for the organisation were developed and several key effort priorities were agreed. The North Star was the organisation’s guiding purpose and the effort priorities represented the key deliverables underpinning it. After that, the entire membership was invited to a brainstorming session which was run in a world-cafe format; roughly 40 members attended, which represented around 75% of members. The delegates were given a briefing on Art Thinking and given problem statements, such as: wouldn’t it be great if …, or how might we … ? Each table had to work through the effort priorities and give them some dimensions and suggest revenue generating projects that, while being imaginative enough to be exciting needed to be capable of being actually implemented. The brainstorming session was professionally facilitated by a consultant.

Inviting artists into the business planning process was also an unconventional (and courageous) step as artists invariably have a strong vision and point of view and they rarely pander to an audience’s tastes; rather they like to explore new territories and bring the audience on the journey with them. Nevertheless, this artist collaboration yielded a large amount of good and useable concepts, which the Board started to implement straight away. Many were great sales ideas. One prompted a themed artist-led and very profitable promotion called 100 by 100, in which 100 members produced one piece (an etching or print) which had to be inspired by something in Ireland’s National Botanical Gardens, and they each made 100 prints of it. This was themed the Botanicals, as Dublin’s Botanical Gardens allowed the show to be exhibited there during their busy season, thus providing GSD not only with a new audience for original art but with a new exhibition venue.

Another initiative was the selection of a street graffiti artist (Dublin’s equivalent of Banksy) to come and make a series of prints in GSD (see

Figure 6). This was a groundbreaking partnership, the artist, Maser, was well known for urban street art, and was an iconic figure in the youth market with a cult following on social media. To get Maser to make a series of fine-art prints was quite a coup for the studio, and the prints he produced sold so well and so fast that they broke all prior records.

Others were that some of the artists’ larger works were showcased in pop-up retail stores in some of Dublin’s busiest shopping thoroughfares, such as the Powerscourt Townhouse Shopping Centre. New markets, new spaces and new audiences were being opened up through this strategy, and the sales were really feeling a dramatic lift. In searching to open up new and larger markets for Irish printmaking, the sponsor’s portfolio was revived, and sales were made to institutional buyers like Yale University, Oxford University and in Ireland to the National Gallery and Trinity College.

The organisation also strengthened its Business to Arts partnerships and forged a deal with one of Ireland’s biggest law firms to produce an original piece of art to go to their 750 best clients. This was a high-ticket, prestigious and profitable programme, putting original art into the homes of hundreds of well-paid business executives.

Figure 7 shows the classification and the range of innovation activity that was undertaken at this time for the organisation. A lot of the activity focused on bringing the work to the attention of new and different audiences, especially people to whom printmaking was relatively unknown. A counter-intuitive feature of this case is that when threatened with the harsh financial crisis, rather than drawing in their horns: cutting costs and commissioning less work, the Board chose to do the opposite. They elected to take a different approach, to ignore the bleak reality and, instead, to imagine a different and better reality for the organisation. They began with plotting a strategic ‘north star’ and navigated towards this desired outcome.