The Impact of Social Servicescape Factors on Customers’ Satisfaction and Repurchase Intentions in Mid-Range Restaurants in Baltic States

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Social Servicescape and Its Implications on Customer Satisfaction

2.2. Linkages between Customer Satisfaction and Repurchase Intentions

3. Methodology

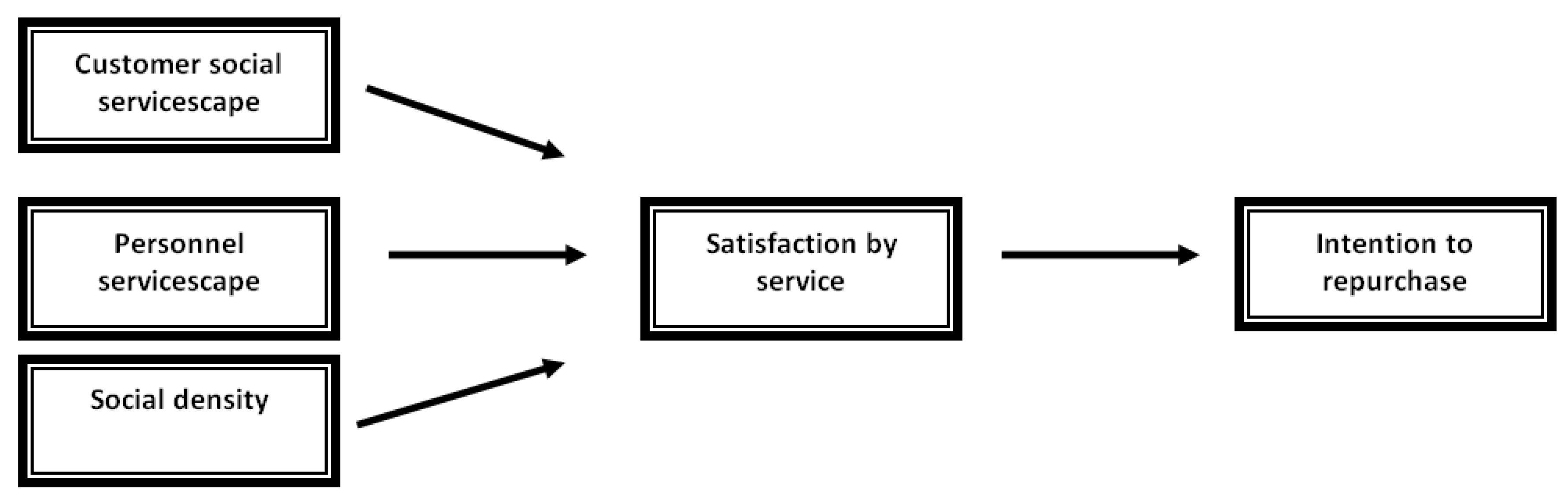

3.1. Research Model and Hypotheses

3.2. Data Collection and Reliability Indicators

4. Results

5. Discussion: Social Servicescape Factors and Open Innovation in Restaurant Services

6. Conclusions and Further Research Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gallarza, M.G.; Ruiz-Molina, M.E.; Gil-Saura, I. Stretching the value-satisfaction-loyalty chain by adding value dimensions and cognitive and affective satisfactions. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 981–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladhari, R.; Souiden, N.; Dufour, B. The role of emotions in utilitarian service settings: The effects of emotional satisfaction on product perception and behavioral intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Su, X.; Hu, X.; Yao, L. App users’ emotional reactions and festival satisfaction: The mediating role of situational involvement. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 980–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S.; Muskat, B.; Del Chiappa, G. Understanding the relationships between tourists’ emotional experiences, perceived overall image, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rychalski, A.; Hudson, S. Asymmetric effects of customer emotions on satisfaction and loyalty in a utilitarian service context. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 71, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Viruel, M.J.; López-Guzmán, T.; Gálvez, J.C.P.; Jara-Alba, C. Emotional perception and tourist satisfaction in world heritage cities: The Renaissance monumental site of úbeda and baeza, Spain. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2019, 27, 100226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Keh, H.T. Consumer reliance on intangible versus tangible attributes in service evaluation: The role of construal level. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 848–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C. Medical tourists’ emotional and cognitive response to credibility and Servicescape. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 1633–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Berchoux, C.; Marek, M.W.; Chen, B. Service quality and customer satisfaction: Qualitative research implications for luxury hotels. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2015, 9, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.; Ko, E.; Joung, H.; Kim, S.J. Chatbot e-service and customer satisfaction regarding luxury brands. J. Bus. Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herstein, R.; Gilboa, S.; Gamliel, E.; Bergera, R.; Ali, A. The role of private label brands in enhancing service satisfaction in the hotel industry: Comparing luxury and boutique hotels. Serv. Mark. Q. 2018, 39, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bufquin, D.; DiPietro, R.; Partlow, C. The influence of the DinEX service quality dimensions on casual-dining restaurant customers’ satisfaction and behavioral intentions. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2017, 20, 542–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.H.; Kim, D.J. Achieving relational outcomes in casual dining restaurants through consumer commitment. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 178–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.; Nisar, T.M.; Knox, D.; Prabhakar, G.P. Understanding customer satisfaction in the UK quick service restaurant industry. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 1207–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, C.J.; Wang, Y.C.; Cai, D.C. Physical factors to evaluate the servicescape of theme restaurants. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2015, 14, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnstone, M.L. The servicescape: The social dimensions of place. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 1399–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.A.; Jeong, M. Effects of e-servicescape on consumers’ flow experiences. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2012, 3, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, E.; Ballantyne, D. Reexamining the place of servicescape in marketing: A service-dominant logic perspective. J. Serv. Mark. 2014, 28, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theron, E.; Pelser, A. Using servicescape to manage student commitment towards a higher education institution. South. Afr. J. High. Educ. 2017, 31, 225–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tankovic, A.C.; Benazic, D. The perception of e-servicescape and its influence on perceived e-shopping value and customer loyalty. Online Inf. Rev. 2018, 42, 1124–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namasivayam, K.; Lin, I.Y. The Servicescape. In Handbook of Hospitality Operations and IT; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2008; pp. 597–598. [Google Scholar]

- Kauppinen-Räisänen, H.; Rindell, A.; Åberg, C. Conveying conscientiousness: Exploring environmental images across servicescapes. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, E.; Park, H.J. The impact of age on gay consumers’ reaction to the physical and social servicescape in gay bars. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalinay, O.; Baxter, I.W.; Collinson, E.; Curran, R.; Gannon, M.J.; Lochrie, S.; Thompson, J. Servicescape and shopping value: The role of negotiation intention, social orientation, and recreational identity at the Istanbul Grand Bazaar, Turkey. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 1132–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brocato, E.D.; Voorhees, C.M.; Baker, J. Understanding the influence of cues from other customers in the service experience: A scale development and validation. J. Retail. 2012, 88, 384–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisk, R.P.; Patrício, L.; Rosenbaum, M.S.; Massiah, C. An expanded servicescape perspective. J. Serv. Manag. 2011, 22, 471–490. [Google Scholar]

- Siguaw, J.A.; Mai, E.; Wagner, J.A. Expanding servicescape dimensions with safety: An exploratory study. Serv. Mark. Q. 2019, 40, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, P.; Siu, N.Y.M. Servicescape elements, customer predispositions and service experience: The case of theme park visitors. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Line, N.D.; Hanks, L.; Kim, W.G. An expanded servicescape framework as the driver of place attachment and word of mouth. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 42, 476–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari, M.; Poggesi, S. Servicescape cues and customer behavior: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Serv. Ind. J. 2013, 33, 171–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombs, A.; McColl-Kennedy, J.R. Social-servicescape conceptual model. Mark. Theory 2003, 3, 447–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Line, N.D.; Hanks, L. The social servicescape: A multidimensional operationalization. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2019, 43, 167–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.T.; DeWitt, T.; Russell-Bennett, R. Service convenience and social servicescape: Retail vs hedonic setting. J. Serv. Mark. 2012, 26, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombs, A.G.; McColl-Kennedy, J.R. Social and spatial influence of customers on other customers in the social-servicescape. Australas. Mark. J. AMJ 2010, 18, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés, B.T.; Cervera-Taulet, A.; García, H.C. Social servicescape effects on post-consumption behavior. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2016, 26, 590–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucia-Palacios, L.; Pérez-López, R.; Polo-Redondo, Y. Can social support alleviate stress while shopping in crowded retail environments? J. Bus. Res. 2018, 90, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Lai, H.J.; Morrison, A.M. Social servicescape and Asian students: An analysis of spring break island bed and breakfast experiences in Taiwan. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 31, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demoulin, N.; Willems, K. Servicescape irritants and customer satisfaction: The moderating role of shopping motives and involvement. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; van Phan, B.; Kim, J.H. The congruity between social factors and theme of ethnic restaurant: Its impact on customer’s perceived authenticity and behavioural intentions. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 40, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Q.; Bogicevic, V. Mattila, A.S. Circular vs. angular servicescape: “Shaping” customer response to a fast service encounter pace. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 89, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Line, N.D.; Hanks, L. A holistic model of the servicescape in fast casual dining. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 288–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Baker, M.A. I earn it, but they just get it: Loyalty program customer reactions to unearned preferential treatment in the social servicescape. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2020, 61, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanks, L.; Line, N.D. The restaurant social servicescape: Establishing a nomological framework. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 74, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Gursoy, D.; Zhang, M. Impact of customer-to-customer interactions on overall service experience: A social servicescape perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 87, 102376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Line, N.D.; Hanks, L. The social servicescape: Understanding the effects in the full-service hotel industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 753–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Line, N.D.; Hanks, L.; Zhang, L. Birds of a feather donate together: Understanding the relationship between the social servicescape and CSR participation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 71, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.; Ro, H.; Kim, T.H. Social servicescape: The impact of social factors on restaurant image and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2015, 16, 290–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aal, E.; Abbas, J.E. Assessing Social and Physical Servicescape as Drivers of Hotels’ Image Formation: Customers Perspective. Int. J. Herit. Tour. Hosp. 2016, 10, 142–160. [Google Scholar]

- Hanks, L.; Line, N.; Yang, W. Status seeking and perceived similarity: A consideration of homophily in the social servicescape. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 60, 1231–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halvorsrud, R.; Kvale, K.; Følstad, A. Improving service quality through customer journey analysis. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2016, 26, 840–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.C.; Ezeh, C. Servicescape and loyalty intentions: An empirical investigation. Eur. J. Mark. 2008, 42, 390–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daunt, K.L.; Harris, L.C. Exploring the forms of dysfunctional customer behaviour: A study of differences in servicescape and customer disaffection with service. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 129–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, G.; Muzellec, L.; Nolan, E. Consumer moments of truth in the digital context: How “search” and “e-word of mouth” can fuel consumer decision making. J. Advert. Res. 2014, 54, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krajnović, A.; Sikirić, D.; Bosna, J. Digital marketing and behavioral economics. Crodim: Int. J. Mark. Sci. 2018, 1, 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira Santini, F.; Ladeira, W.J.; Sampaio, C.H.; Perin, M.G. Online banking services: A meta-analytic review and assessment of the impact of antecedents and consequents on satisfaction. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2018, 23, 1678–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belás, J.; Gabčová, L. The relationship among customer satisfaction, loyalty and financial performance of commercial banks. Econ. Manag. 2016, 19, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, K.; Diljit, S. Antecedents of customer loyalty: Does service quality suffice? Malays. J. Libr. Inf. Sci. 2017, 16, 95–113. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, T.; Yi, Y. The effect of service quality on customer satisfaction, loyalty, and happiness in five Asian countries. Psychol. Mark. 2018, 35, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, R. The moderating role of customer engagement experiences in customer satisfaction–loyalty relationship. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 1278–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasiova, Y.A. Сoциальнo-психoлoгические oсoбеннoсти пoстпoкупательскoгo пoведения = socio-psychological peculiarities of post-purchase behavior. Ph.D. Thesis, Russian State Governance University, Moscow, Russia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, Q. Cultivating loyal customers through online customer communities: A psychological contract perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 103, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friend, S.B.; Johnson, J.S.; Luthans, F.; Sohi, R.S. Positive psychology in sales: Integrating psychological capital. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2016, 24, 306–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Castellanos-Verdugo, M.; Vega-Vázquez, M.; Oviedo-García, M.Á.; Orgaz-Agüera, F. The relevance of psychological factors in the ecotourist experience satisfaction through ecotourist site perceived value. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 124, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Zhang, L. Psychological Contract Breach and Customer Satisfaction: A Study of Online Shopping. Serv. Mark. Q. 2019, 40, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McCusker, K.; Gunaydin, S. Research using qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods and choice based on the research. Perfusion 2015, 30, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The Use of Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in International Marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M.S.; Massiah, A.C. When Customers Receive Support from Other Customers: Exploring the Influence of Intercustomer Social Support on Customer Voluntary Performance. J. Serv. Res. 2007, 9, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, T.D.; Parry, C.D. A third place in the everyday lives of people living with cancer: Functions of Gilda’s Club of Greater Toronto. Health Place 2009, 15, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Specht, N.; Fichtel, S.; Meyer, A. Perception and attribution of employees’ effort and abilities: The impact on customer encounter satisfaction. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2007, 18, 534–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eroglu, S.A.; Machleit, K. An Empirical Study of Retail Crowding: Antecedents and Consequences. J. Retail. 1990, 66, 201–221. [Google Scholar]

- Machleit, K.; Eroglu, S.; Mantel, S.P. Perceived Retail Crowding and Shopping Satisfaction: What Modifies This Relationship? J. Consum. Psych. 2000, 9, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, K.M.; Bateson, J.E.G. Perceived Control and the Effects of Crowding and Consumer Choice on the Service Experience. J. Consum. Res. 1991, 18, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, J.A. Undiscovering Dimensionality in the Servicescape: Towards Legibility. Serv. Ind. J. 2007, 27, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olorunniwo, F.; Hsu, K.M.; Udo, G.J. Service quality, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intentions in the service factory. J. Serv. Mark. 2006, 20, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, R.T.; Williams, D.C. How length of patronage affects the impact of customer satisfaction on repurchase intention. J. Consum. Satisf. Dissatisf. Complain. Behav. 1994, 3, 126–138. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, J.J., Jr.; Brady, M.K.; Hult, G.T.M. Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. J. Retail. 2000, 76, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihtiyar, A.; Ihtiyar, H.G.; Galay, Y. Exploration of the antecedents and consequences of customers’ service experiences. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2018, 1, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, I.; van Steenburg, E. Me first, then the environment: Young millennials as green consumers. Young Consum. 2018, 19, 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hight, S.K.; Park, J.Y. Role stress and alcohol use on restaurant server’s job satisfaction: Which comes first? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, G.M.; Artino, A.R. Analyzing and interpreting data from Likert-type scale. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2013, 12, 541–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jamieson, S. Likert scales: How to (ab)use them. Med. Educ. 2004, 38, 1212–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, G. Likert scales, levels of measurement and the “laws” of statistics. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2010, 2, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardelis, K. Moksliniųtyrimųmetodologijairmetodai; Judex: Kaunas, Lithuania, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mooi, E.A.; Sarstedt, M. A Concise Guide to Market Research: The Process, Data, and Methods Using IBM SPSS Statistics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Amrhein, V.; Korner-Nievergelt, F.; Roth, T. The earth is flat (p > 0.05): Significance thresholds and the crisis of unreplicable research. Peer J. 2017, 5, e3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tenenhaus, M.; Vinzi, V.E.; Chatelin, Y.M.; Lauro, C. PLS path modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2005, 48, 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzels, M.; Odekerken-Schröder, G.; van Oppen, C. Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: Guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Q. 2009, 33, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modelling in international marketing. Adv. Int. Mark. 2009, 20, 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Wexley, K.N.; Alexander, R.A.; Greenawalt, J.P.; Couch, M.A. Attitudinal congruence and similarity as related to interpersonal evaluations in manager-subordinate dyads. Acad. Manag. J. 1980, 23, 320–330. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J.R. Problems with the use of profile similarity indices in the study of congruence in organizational research. Pers. Psychol. 1993, 46, 641–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosasih, U.; Wahyudin, W.; Prabawanto, S. September, An Analysis of Looking Back Method in Problem-Based Learning: Case Study on Congruence and Similarity in Junior High School. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 895, 012074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, G.; Dave, K. Exploration of Service Quality Factors in the Restaurant Industry: A Study of Selected Restaurants in the New Delhi Region. In Hospitality Marketing and Consumer Behavior: Creating Memorable Experiences; Jauhari, V., Ed.; Apple Academic Press: Waretown, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins, G.P. South America into the 1990s: Evolving International Relationships in A New Era; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019; p. 211. [Google Scholar]

- Smedley, K. Age Matters: Employing, Motivating and Managing Older Employees; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lestari, S.I.P.; Ambarwati, R.; Agustina, T.; Muryani, E.; Andriani, A.; Alfani, M. The effect of customer’s orientation of service employee on customer’s satisfaction of health services. Int. J. Econ. Bus. Adm. 2019, 7, 270–278. [Google Scholar]

- Vilnai-Yavetz, I.; Gilboa, S. The effect of servicescape cleanliness on customer reactions. Serv. Mark. Q. 2010, 31, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collisson, B.; Howell, J.L.; Harig, T. Foodie Calls: When Women Date Men for a Free Meal (Rather Than a Relationship). Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heung, V.C.; Gu, T. Influence of restaurant atmospherics on patron satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 1167–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilelienė, L.; Grigaliūnaitė, V. Vartotojųpasitenkinimo Čili pica picerijųpaslaugomisnustatymas. Organ. Sist. 2012, 64, 69–85. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H. Open Services Innovation: Rethinking Your Business to Grow and Compete in a New Era; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Acosta, M.; Coronado, D.; Ferrándiz, E. Trends in the Acquisition of External Knowledge for Innovation in the Food Industry. In Open Innovation in the Food and Beverage Industry; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H.; Kim, S.; Agogino, A. Chez Panisse: Building an open innovation ecosystem. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2014, 56, 144–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J.; Park, K.; Gaudio, G.D.; Corte, V.D. Open innovation ecosystems of restaurants: Geographical economics of successful restaurants from three cities. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherbak, V. Open innovations as a tool of restaurant business effective activity. Менеджмент 2016, 24, 115–127. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, N.; Line, N.D.; Merkebu, J. The impact of brand prestige on trust, perceived risk, satisfaction, and loyalty in upscale restaurants. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2016, 25, 523–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M.G. Co-Creation of Value with Consumers as an Innovation Strategy in the Food and Beverage Industry: The Case of Molson Coors ‘Talking Can’. In Open Innovation in the Food and Beverage Industry; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2013; pp. 1353–1391. [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe, O.M. Service quality, customer satisfaction and loyalty: The moderating role of gender. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2011, 12, 278–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bayona-Saez, C.; Cruz-Cázares, C.; García-Marco, T.; García, M.S. Open innovation in the food and beverage industry. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 526–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Item | Mean | Median | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Customer Social Servicescape | |||

| Congruent physical appearance | 4.7 | 5 | 1.12 |

| Congruent social status | 5.1 | 5 | 1.24 |

| Congruent age | 3.4 | 3 | 0.91 |

| Similar behavior manners | 5.8 | 6 | 1.26 |

| Congruent number of visitors | 4.2 | 4 | 1.41 |

| Congruent composition of visitors | 3.9 | 4 | 1.27 |

| Cronbach’s alpha coefficient = 0.802 | |||

| Personnel Servicescape | |||

| Congruent physical appearance | 4.1 | 4 | 1.26 |

| Congruent willingness to communicate | 5.2 | 5 | 1.31 |

| Congruent age | 2.9 | 3 | 0.96 |

| Cronbach’s alpha coefficient = 0.854 | |||

| Social Density | |||

| Number of tables in a restaurant | 5.3 | 5 | 1.33 |

| Distance between sitting places | 5.7 | 6 | 1.2 |

| The necessity of private tables | 4.1 | 4 | 1.04 |

| Queues to restrooms | 5.1 | 5 | 0.93 |

| Cronbach’s alpha coefficient = 0.761 | |||

| Mean (Gender) | t-Test for Equality of Means | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | t | Sig. (2-Tailed) | |

| Social servicescape | 4.03 | 4.81 | −1.12 | 0.148 |

| Personnel servicescape | 3.74 | 4.4 | −1.31 | 0.124 |

| Social density | 4.58 | 5.29 | −1.67 | 0.071 |

| Descriptive Statistics | t-Test for Equality of Means | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | |||||||

| Mean | Median | Std. Deviation | Male | Female | t | Sig. 2-Tailed | |

| Satisfaction by services provided | 4.9 | 5 | 0.86 | 5.2 | 4.5 | −1.31 | 0.151 |

| Intentions to revisit | 4.7 | 5 | 1.13 | 5 | 4.2 | −1.07 | 0.186 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morkunas, M.; Rudienė, E. The Impact of Social Servicescape Factors on Customers’ Satisfaction and Repurchase Intentions in Mid-Range Restaurants in Baltic States. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 77. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/joitmc6030077

Morkunas M, Rudienė E. The Impact of Social Servicescape Factors on Customers’ Satisfaction and Repurchase Intentions in Mid-Range Restaurants in Baltic States. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. 2020; 6(3):77. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/joitmc6030077

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorkunas, Mangirdas, and Elzė Rudienė. 2020. "The Impact of Social Servicescape Factors on Customers’ Satisfaction and Repurchase Intentions in Mid-Range Restaurants in Baltic States" Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 6, no. 3: 77. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/joitmc6030077