Business Model Dynamics from Interaction with Open Innovation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background and State-of-the-Art

2.1. Competitive Challenges for Incumbent Companies

2.2. What Is a Business Model?

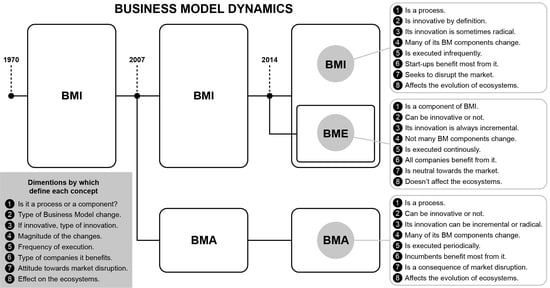

2.3. Business Model Dynamics

2.4. What Is Business Model Adaptation?

2.5. What Is Business Model Innovation?

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

- (d)

- (e)

- Changing and adapting business models through time. This group of studies refers to Business Model Dynamics, the evolution and adaptation of business models. Little is known about this sub-domain and academics agree on a general feeling that a better understanding of the evolution of a Business Model through time is needed [6,7,24,28,49].

2.6. Strategic Connection of Business Models Dynamics Instances

“To what extent should one be used and not the other to provide a sound strategic value appropriation?”

3. Research Methodology: Meta-Synthesis

3.1. Why Meta-Synthesis?

3.2. Data Collection, Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Dimension 1: About the Nature of BMA

- Is Business Model Adaptation a specific process or is it a form of BMI? Some authors believe that BMA is a form of BMI while others think that is a completely different process. In Section 4.3.1 of the synthesis, the differences in opinions are analyzed and summarized.

- Is Business Model Adaptation innovative per se? Authors discuss the innovativeness of the BMA processes and the degree of radicalness. Section 4.3.2 is a comparison of the different opinions regarding the degree of innovation of both processes.

- How many components must change to be considered a Business Model Adaptation? Authors discuss the scope of the change based on the different components of a business model that are affected. Section 4.3.3 is a summary of their beliefs from the point of view of how narrow or wide are the changes on the Business Model components.

- Is BMA a continuous change or is it infrequent? The frequency of change in the process of BMA is discussed by several authors. In Section 4.3.4, the occurrence of BMA and BMI is analyzed.

- Is BMA for start-ups or for incumbents? Authors debate to what extent the process of BMA and BMI are suitable for different types of companies. Section 4.3.5 summarizes the conveniences of BMA and BMA for start-ups and incumbents.

- What is the attitude towards the market? Authors deliberate about the planned outcome of BMA and BMI. Section 4.3.6 illustrates the different outcomes of these two processes.

4.2. Dimension 2: Theories to Explain BMA

- Business Model Adaptation through the lenses of the Dynamic Capabilities theory. Different authors analyze the BMA phenomena from the point of view of the Dynamic Capabilities theory. Section 4.1 summarizes their findings.

- Business Model Adaptation through the lenses of the Resource Based View. In Section 4.2, we summarize the findings of the authors that analyze BMA from these other lenses.

4.3. Comparing and Synthesizing (I): Stating the Nature of BMA

4.3.1. Is BMA a Specific Process or Is It a Form of BMI?

Summary

- Business Model Innovation: as the broader process with the objective to create a new Business Model.

- Business Model Adaptation: as a process with the objective to adapt a current Business Model, and that can be a form of BMI if it becomes innovative.

- Business Model Evolution: as a component of a wider process of transformation that seeks the change of a Business Model through small incremental changes in the current model.

4.3.2. Is BMA Innovative Per Se?

Summary

4.3.3. How Many Components Do We Need to Change to Consider BMI and Not Just BMA or BME?

Summary

4.3.4. What Is the Frequency of the Changes in BME, BMA, and BMI?

Summary

4.3.5. Is BMA for Start-Ups or Is It for Incumbents?

- When their current strategy or business model is clearly inappropriate and the firm is facing a crisis (e.g., Kresge introducing the discount retail concept in the 1960s and renaming itself K-Mart) [15].

- When they are attempting to scale up a new-to-the-world product to make it attractive to the mass market [15].

Summary

4.3.6. The Market Makes You Change, or Are You Changing the Market?

Summary

4.4. Comparing and Synthesizing (II): Findings on Theories to Explain BMD

4.4.1. BMA and BMI as a Dynamic Capability of a Firm

Summary

4.4.2. BMA and BMI and the Resource-Based View (RBV)

Summary

5. Discussion

5.1. Conceptual Coherence of BMD Instances

5.2. Connection of BMD Instances to Strategy Implementation

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Limitations

6.3. New Lines for Further Research

6.3.1. Scenario Modeling

6.3.2. BME, BMA, and BMI from the Lenses of the Contingency Theory

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dottore, A.G. Business model adaptation as a dynamic capability: A theoretical lens for observing practitioner behaviour. In Proceedings of the 22nd Bled eConference eEnablement: Facilitating an Open, Effective and Representative eSociety, BLED 2009 Proceedings, Bled, Slovenia, 14–17 June 2009; pp. 484–505. [Google Scholar]

- Casadesus-Masanell, R.; Ricart, J. From Strategy to Business Models and to Tactics. Long Range Plann. 2010, 43, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. Business model innovation: It’s not just about technology anymore. Strateg. Leadersh. 2007, 35, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- West, J.; Salter, A.; Vanhaverbeke, W.; Chesbrough, H. Open innovation: The next decade. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. Open Business Models: How to Thrive in the New Innovation Landscape; Harvard Business Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 6 December 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y.; Tucci, C.L. Clarifying Business Models: Origins, Present, and Future of the Concept. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2005, 16, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saebi, T.; Lien, L.; Foss, N.J. What Drives Business Model Adaptation? The Impact of Opportunities, Threats and Strategic Orientation. Long Range Plann. 2017, 50, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharma, S.; Dixit, M.R.; Karna, A. Design leaps: Business model adaptation in emerging economies. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2016, 10, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, C.; Karna, A.; Sailer, M. Business model adaptation for emerging markets: A case study of a German automobile manufacturer in India. R D Manag. 2016, 46, 480–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snihur, Y.; Thomas, L.D.W.; Burgelman, R.A. An Ecosystem-Level Process Model of Business Model Disruption: The Disruptor’s Gambit. J. Manag. Stud. 2018, 55, 1278–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson, M.W.; Christensen, C.M. Reinventing your business model. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 16, 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R. Business Model Design and the Performance of Entrepreneurial Firms. Organ. Sci. 2007, 18, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, N.J.; Saebi, T. Fifteen Years of Research on Business Model Innovation: How Far Have We Come, and Where Should We Go? J. Manag. 2016, 43, 200–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- DaSilva, C.M.; Trkman, P.; Desouza, K.; Lindič, J. Disruptive technologies: A business model perspective on cloud computing. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2013, 25, 1161–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markides, C. Disruptive Innovation: In Need of Better Theory*. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2006, 23, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbo, L.; Pirolo, L.; Rodrigues, V. Business model adaptation in response to an exogenous shock: An empirical analysis of the Portuguese footwear industry. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2018, 10, 1847979018772742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. Business model innovation: Opportunities and barriers. Long Range Plann. 2010, 43, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayna, T.; Striukova, L. From rapid prototyping to home fabrication: How 3D printing is changing business model innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 102, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Argyris, C.; Schon, D. Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Approach; Addision Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1978; p. 344. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, D.J.; Argyris, C.; Schon, D.A. Organizational Learning II: Theory, Method, and Practice. Ind. Labor Relat. Rev. 1997, 50, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, M.; Shlonsky, A. Systematic Synthesis of Qualitative Research; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M. Business model innovation: Past research, current debates, and future directions. J. Strategy Manag. 2017, 10, 342–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achtenhagen, L.; Melin, L.; Naldi, L. Dynamics of business models—Strategizing, critical capabilities and activities for sustained value creation. Long Range Plann. 2013, 46, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Casadesus-Masanell, R.; Zhu, F. Business model innovation and competitive imitation: The case of sponsor-based business models. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 464–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wirtz, B.W.; Pistoia, A.; Ullrich, S.; Göttel, V. Business Models: Origin, Development and Future Research Perspectives. Long Range Plann. 2016, 49, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andries, P.; Debackere, K. Adaptation in New Technology-Based Ventures: Insights at the Company Level; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 8, pp. 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H.; Rosenbloom, R.S. The role of the business model in capturing value from innovation: Evidence from Xerox Corporation’s technology spin-off companies. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2002, 11, 529–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chesbrough, H.; Bogers, M. Explicating Open Innovation: Clarifying an Emerging Paradigm for Understanding Innovation Keywords. New Front. Open Innov. 2014, 15, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, J.J.; Zhao, X. Business model innovation through a rectangular compass: From the perspective of open innovation with mechanism design. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J. The Relationship Between Open Innovation, Entrepreneurship, and Business Model. In Business Model Design Compass; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Saebi, T.; Foss, N.J. Business Models for Open Innovation: Matching Heterogenous Open Innovation Strategies. Eur. Manag. J. 2015, 33, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yun, J.J. Business Model Design Compass: Open Innovation Funnel to Schumpeterian New Combination Business Model Developing Circle; Springer: Singapore, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, J.J.; Yang, J.; Park, K. Open Innovation to Business Model: New Perspective to connect between technology and market. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2016, 21, 324–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feller, J.; Finnegan, P.; Nilsson, O. Open innovation and public administration: Transformational typologies and business model impacts. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2011, 20, 358–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiblen, T. The Open Business Model: Understanding an Emerging Concept. J. Multi Bus. Model Innov. Technol. 2016, 2, 35–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezger, F. Toward a capability-based conceptualization of business model innovation: Insights from an explorative study. R D Manag. 2014, 44, 429–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lungu, M.F. Achieving strategic agility through business model innovation. The case of telecom industry. Proc. Int. Conf. Bus. Excell. 2018, 12, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Osiyevskyy, O.; Dewald, J. Inducements, Impediments, and Immediacy: Exploring the Cognitive Drivers of Small Business Managers’ Intentions to Adopt Business Model Change. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 1011–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. The foundations of enterprise performance: Dynamic and ordinary capabilities in an (economic) theory of firms. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 28, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.; Lee-Kelley, L. Unpacking the theory on ambidexterity: An illustrative case on the managerial architectures, mechanisms and dynamics. Manag. Learn. 2013, 44, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Täuscher, K.; Abdelkafi, N. Visual tools for business model innovation: Recommendations from a cognitive perspective. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2017, 26, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Täuscher, K.; Laudien, S.M. Understanding platform business models: A mixed methods study of marketplaces. Eur. Manag. J. 2018, 36, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yip, A.W.H.; Bocken, N.M.P. Sustainable business model archetypes for the banking industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 150–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappa, M. Business Models on the Web. 2001. Available online: http://digitalenterprise.org/models/models.html (accessed on 17 March 2019).

- Timmers, P. Business Models for Electronic Markets. Electron. Mark. 2007, 8, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, B.W.; Schilke, O.; Ullrich, S. Strategic development of business models: Implications of the web 2.0 for creating value on the internet. Long Range Plann. 2010, 43, 272–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, B.W.; Daiser, P. Business Model Innovation Processes: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Bus. Model. 2018, 6, 40–58. [Google Scholar]

- Pateli, A.G.; Giaglis, G.M. A research framework for analysing eBusiness models. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2004, 13, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, L.; Broman, C.; Robèrt, G.; Basile, K.; Trygg, G. An approach to business model innovation and design for strategic sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. The future of open innovation: The future of open innovation is more extensive, more collaborative, and more engaged with a wider variety of participants. Res. Technol. Manag. 2017, 60, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andries, P.; Debackere, K. Adaptation and Performance in New Businesses: Understanding the Moderating Effects of Independence and Industry. Small Bus. Econ. 2007, 29, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnsack, R.; Pinkse, J.; Kolk, A. Business models for sustainable technologies: Exploring business model evolution in the case of electric vehicles. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Study Guide for Essentials of Nursing Research, Appraising Evidence for Nursing Practice, 6th ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, S.; Jensen, L.; Kearney, M.H.; Noblit, G.; Sandelowski, M. Qualitative metasynthesis: Reflections on methodological orientation and ideological agenda. Qual. Health Res. 2004, 14, 1342–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandelowski, M.; Barroso, J. Handbook for Synthesizing Qualitative Research; Springer Publish Co.: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, S.M. A Research Metasynthesis on Digital Video Composing in Classrooms. J. Lit. Res. 2013, 45, 386–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopfer, M.; Fallahi, S.; Kirchberger, M.; Gassmann, O. Adapt and strive: How ventures under resource constraints create value through business model adaptations. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2017, 26, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, J.; Holmén, M. Capabilities and radical changes of the business models of new bioscience firms. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2009, 18, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante, S.; Kesting, P.; Ulhøi, J. Business model dynamics and innovation: Re-establishing the missing linkages. Manag. Decis. 2011, 49, 1327–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miller, K.; Mcadam, M.; Mcadam, R. The changing university business model: A stakeholder perspective. R D Manag. 2014, 44, 265–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, S.W.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Barlow, C.Y.; Chertow, M.R. From refining sugar to growing tomatoes: Industrial ecology and business model evolution. J. Ind. Ecol. 2014, 18, 603–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboni, B.; Bortoluzzi, G. Business Model Adaptation and the Success of New Ventures. J. Entrep. Manag. Inov. 2015, 11, 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, M.-S.; Hall, S.; Hardy, J.; Workman, M. Valuing energy futures; a comparative analysis of value pools across UK energy system scenarios. Appl. Energy 2017, 206, 815–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolkamp, J.C.C.M.; Huijben, J.C.C.M.; Mourik, R.M.; Verbong, G.P.J.; Bouwknegt, R. User-centred sustainable business model design: The case of energy efficiency services in the Netherlands. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, S.S.T.; Straker, K.; Wrigley, C. The typologies of power: Energy utility business models in an increasingly renewable sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 195, 1032–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, B.; Khazami, N.; Ymeri, P.; Fogarassy, C. Investigating the current business model innovation trends in the biotechnology industry. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2019, 20, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bair, C.R. Meta-synthesis: A new research methodology. In Educational Research Association Annual Meeting; University of Texas Press: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- van de Ven, A.H. Suggestions for studying strategy process: A research note. Strateg. Manag. J. 1992, 13, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Plann. 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saebi, T. Business Model Evolution, Adaptation or Innovation? A Contingency Framework on Business Model Dynamics, Environmental Change and Dynamic Capabilities; Oxford Univeristy Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; Volume 1, pp. 1625–1678. [Google Scholar]

- Sosna, S.R.; Trevinyo-Rodríguez, M.; Velamuri, R.N. Business model innovation through trial-and-error learning: The Naturhouse case. Long Range Plann. 2010, 43, 383–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, A.; Verona, G.; Rothaermel, F.T. Unpacking the Disruption Process: New Technology, Business Models, and Incumbent Adaptation. J. Manag. Stud. 2018, 55, 1166–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhide, A. The Origin and Evolution of New Businesses; Oxfort Univeristy Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy; Harper and Brothers: Manhattan, NY, USA, 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Various. HBR’s must-reads on strategy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2000, 16, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Doz, Y.L.; Kosonen, M. Embedding strategic agility: A leadership agenda for accelerating business model renewal. Long Range Plann. 2010, 43, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Martin, J.A. Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and micro foundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. Strat. Mgmt. J 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nailer, C.; Buttriss, G. Processes of business model evolution through the mechanism of anticipation and realisation of value. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 91, 671–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Sapienza, H.J.; Davidsson, P. Entrepreneurship and dynamic capabilities: A review, model and research agenda. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 917–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teece, D.J. Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Plann. 2018, 51, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbert, S.L. Empirical research on the resource-based view of the firm: An assessment and suggestions for future research. Strateg. Manag. J. Strat. Mgmt. J. 2007, 28, 121–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, E.T. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz, B.W.; Göttel, V.; Daiser, P. Business Model Innovation: Development, Concept and Future Research Directions. J. Bus. Model. 2016, 4, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hacklin, F.; Björkdahl, J.; Wallin, M.W. Strategies for business model innovation: How firms reel in migrating value. Long Range Plann. 2018, 51, 82–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Keywords | Number of Articles | |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Business Model Adaptation’ | 17 | |

| ‘Business Model Innovation’ | Adaptation/‘to adapt’ | 25 |

| ‘Business Model Innovation’ | ‘Business Model Evolution’ | 5 |

| Title | Author | Term Usage | Citations | Publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The role of the business model in capturing value from innovation: evidence from Xerox Corporation’s technology spin-off companies | Chesbrough, H. Rosenbloom, Richard S. (2002) [28] | BMI + adaptation. | 5092 | Industrial and corporate change |

| A research framework for analyzing eBusiness models | Pateli, A G Giaglis, G M (2004) [49] | BMI + ‘to adapt a BM’ | 484 | European journal of information systems |

| Adaptation in new technology-based ventures: insights at the company level | Andries, P; Debackere, K (2007) [27] | BMA | 122 | International Journal of Management Reviews |

| Reinventing your business model | Johnson, M W Christensen, C M (2008) [11] | BMI + adaptation | 3032 | Harvard Business Review |

| Capabilities and radical changes of the business models of new bioscience firms | Brink, Johan Holmén, Magnus (2009) [59] | BMI + adaptation | 68 | Creativity and Innovation Management |

| Business Model Adaptation as a dynamic capability: a theoretical lens for observing practitioner behavior | Dottore, AG (2009) [1] | Uses both BMI + BMA | 15 | BLED 2009 Proceedings |

| Business model innovation: Opportunities and barriers | Chesbrough, Henry (2010) [17] | BMI + adaptation | 3267 | Long Range Planning |

| Strategic development of business models: Implications of the web 2.0 for creating value on the internet | Wirtz, Bernd W. Schilke, Oliver Ullrich, Sebastian (2010) [47] | BMA | 701 | Long Range Planning |

| Business model dynamics and innovation: Re-establishing the missing linkages | Cavalcante, S., Kesting, P., Ulhøi, J. (2011) [60] | BMI + adaptation | 480 | Management Decision |

| Dynamics of Business Models–Strategizing, Critical Capabilities and Activities for Sustained Value Creation | Achtenhagen, L., Melin, L., Naldi, L. (2013) [23] | BMA | 366 | Long Range Planning |

| Business models for sustainable technologies: Exploring business model evolution in the case of electric vehicles | Bohnsack, René Pinkse, Jonatan Kolk, Ans (2014) [53] | BMI + Business Model Evolution | 425 | Research Policy |

| The changing university business model: a stakeholder perspective | Miller, K. Mcadam, M. Mcadam, R. (2014) [61] | BMI + Business Model Evolution | 164 | R and D Management |

| Toward a capability-based conceptualization of business model innovation: Insights from an explorative study | Mezger, Florian (2014) [37] | Uses both BMI + BMA | 125 | R and D Management |

| From refining sugar to growing tomatoes: Industrial ecology and business model evolution | Short, S. W. Bocken, Nancy Barlow, Claire Y Chertow, Marian R (2014) [62] | BMI + Business Model Evolution | 88 | Journal of Industrial Ecology |

| Business Model Adaptation and the Success of New Ventures | Balboni, B; Bortoluzzi, G (2015) [63] | Uses both BMI + BMA | 11 | Journal of Entrepreneurship Management and Innovation |

| Business Model Adaptation for emerging markets: a case study of a German automobile manufacturer in India | Landau, C; Karna, A; Sailer, M (2016) [9] | Uses both BMI + BMA | 27 | R&D Management |

| Design leaps: Business Model Adaptation in emerging economies | Sharma, S; Dixit, MR; Karna, A (2016) [8] | Uses both BMI + BMA | 4 | Journal of Asia Business Studies |

| What Drives Business Model Adaptation? The Impact of Opportunities, Threats and Strategic Orientation | Saebi, T; Lien, L; Foss, NJ (2017) [7] | Uses both BMI + BMA | 92 | Long Range Planning |

| Adapt and strive: How ventures under resource constraints create value through business model adaptations | Dopfer M, Fallahi S, Kirchberger M, Gassmann O. (2017) [58] | Uses both BMI + BMA | 7 | Creativity and Innovation Management |

| Valuing energy futures; a comparative analysis of value pools across UK energy system scenarios | Wegner, MS; Hall, S; Hardy, J; Workman, M (2017) [64] | Uses both BMI + BMA | 5 | Applied Energy |

| User-centered sustainable business model design: The case of energy efficiency services in the Netherlands | Tolkamp, J. Huijben, J.C.C.M. Mourik, R.M. Verbong, G.P.J. Bouwknegt, R. (2018) [65] | Uses both BMI + BMA | 15 | Journal of Cleaner Production |

| The typologies of power: Energy utility business models in an increasingly renewable sector | Bryant, ST. Straker, K Wrigley, C (2018) [66] | Uses both BMI + BMA | 5 | Journal of Cleaner Production |

| An Ecosystem-Level Process Model of Business Model Disruption: The Disruptor’s Gambit | Snihur, Y; Thomas, Ll.D.W.; Burgelman, R (2018) [10] | BMI + adaptation | 3 | Journal of Management Studies |

| Business Model Adaptation in response to an exogenous shock: An empirical analysis of the Portuguese footwear industry | Corbo, L; Pirolo, L; Rodrigues, V (2018) [16] | BMA | 2 | International Journal of Engineering Business Management |

| Investigating the current business model innovation trends in the biotechnology industry | Horvath, B; Khazami, N; Ymeri, P; Fogarassy, C (2019) [67] | BMI + Business Model Evolution | 7 | Journal of Business Economics and Management |

| Dimension | Key Points and Themes |

|---|---|

| The nature of BMA |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Theories to explain BMA |

|

|

| BM Adaptation as Part of a Process of BMI | Findings | Author |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Research to date is yet to satisfy the need for methods that can structure a firm’s change endeavor either towards adopting a new business model or extending a current one to include new dimensions.’ | Adaptation of a BM is part of the BMI process. | Pateli and Giaglis (2004) [49] |

| ‘(…) The third is to compare that model to your existing model to see how much you’d have to change it to capture the opportunity.’ | First, you create the concept of a new model, then you adapt your actual business model. | Johnson and Christensen (2008) [11] |

| This makes a ‘radical’ change empirically and analytically distinct from the slight alteration or adaptation of the initial business model which frequently occur within entrepreneurial ventures. | Adaptation of a business model is different from radical changes in Business Models even if they all are part of a BMI process. | Brink and Holmén (2009) [59] |

| ‘Business Model Innovation is not a matter of superior foresight ex ante—rather, it requires significant trial and error and quite a bit of adaptation ex post. In fact, it is the product of extensive experimentation.’ | Adaptation is part of the process of BMI. | Chesbrough (2010) [17] |

| Business Model Evolution | Findings | Author |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Business model evolution shows a series of incremental changes that introduce service-based components (…)’ | BME is the creation of new BM through a series of incremental changes. | Bohnsack et al. (2014) [53] |

| ‘(…) technology transfer office staff and government support agency representatives have led to the university business model evolving not as a process of co-creation but rather in a series of transitions (…)’ | BME is a series of transitions on the Business Model. | Miller et al. (2014) [61] |

| ‘New ventures dynamically adapt and re-configure their business model’ | BMs adapt and evolve. | Balboni and Bortoluzzi (2015) [63] |

| ‘The research employs a circular evaluation method to detect which parts of the applied business structures show model evolution of an innovative and knowledge-intensive industry, biotechnology.’ | Different parts of the business model show evolution. | Horvath et al. (2019) [67] |

| BMA is a Form of BMI | Findings | Author |

|---|---|---|

| ‘For established firms, BMI could be either the adaptation of its existing (core) business model or the development and introduction of a new business model adjacent to its core business.’ | BMA is a form of BMI. | Mezger (2014) [37] |

| ‘Business Model Adaptation is a form of Business Model Innovation that addresses the development of a business model to better fit a new context’ | BMA is a form of BMI. | Landau et al. (2016) [9] |

| ‘The process of continuous search, selection, and improvement of a Business Model based on the surrounding environment.’ | The role and nature of Business Model Adaptation as a coping mechanism with resource constraints. | Dopfer et al. (2017) [58] |

| BMA and Innovation | Findings | Author |

|---|---|---|

| ‘The strategic potential of business model innovation thus lies in identifying new sources of value creation, based on innovations of the different components of a business model and/or the interactions between these components.’ | BMI is based on the innovation of the different components of a Business Model. | Bohnsack et al. (2014) [53] |

| ‘Entrepreneurs interested in exploring and exploiting opportunities in these markets need to overcome multiple innovation challenges to activate and sustain interest in what they have to offer.’ | BMA can be innovative | Sharma et al. (2016) [8] |

| ‘This article clarifies the relationship between business model innovation enabled by 3D printing technologies and the resulting innovative effect, whether radical or incremental.’ | BMI is innovative (by definition) but can be either incremental or radical. | Rayna and Striukova (2016) [18] |

| ‘Business Model Adaptation is a form of Business Model Innovation that addresses the development of a business model to better fit a new context’ | BMA is innovative as is a form of Business Model Innovation. | Landau et al. (2016) [9] |

| ‘Business Model Adaptation and innovation differ in important ways. (…), while the kind of novelty implied by the notion of an ‘innovation’ might be a likely outcome of business model adaptation, it is not a necessary requirement. Business Model Adaptation can be non-innovative.’ | BMA can be innovative and non-innovative, while BMI is innovative. | Saebi et al. (2017) [7] |

| BMA and Innovation | Findings | Author |

|---|---|---|

| ‘In spite of these similarities, the finding that adaptation in new ventures can imply gradual as well as radical business model changes goes against the traditional view on dynamic capabilities.’ | BMA can imply gradual as well as radical changes. | Andries and Debackere (2006) [27] |

| ‘The process of business model evolution involves important learning activities in which the firm develops new skills and abilities, the mind-set of innovation and adaptation, and an appetite for searching out new value creation opportunities. | The process implies incremental innovation in the firm. | Short et al. (2014) [71] |

| ‘Business model evolution shows a series of incremental changes that introduce service-based components, which were initially developed by entrepreneurial firms, to the product.’ | In BME the changes are incremental | Bohnsack et al. (2014) [53] |

| ‘AutoLux adapted its business model in a sequential manner to step-by-step overcome the challenges of operating in an emerging market and to design a model that fits the new context’ | Adaptation can be sequential to overcome step-by-step the challenges of operating in an emerging market and to design a model that fits the new context. | Landau et al. (2016) [9] |

| ‘Involving the user requires facilitation of opportunities for interaction in multiple components of the business model and can lead to both incremental and radical business model innovation ex-post.’ | BMI can be either incremental or radical. | Tolkamp et al. (2018) [65] |

| ‘Any component of the business model can change after involving the user; however, most changes tend to be incremental changes to the value proposition and components that enable the value proposition (key activities, -resources and -partnerships).’ | When adapting a BM to become user-centered, changes tend to be incremental and targeting value proposition components. | Tolkamp et al. (2018) [65] |

| Changes in Business Model Components | Findings | Author |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Customer needs, market misalignments and the ability to sense new technological potential have been the major common drivers of the dynamics of these firms’ BMA processes’ | To succeed with the adaptation process, some components of the BM should change. | Balboni and Bortoluzzi (2015) [63] |

| ‘Firms are increasingly confronted with fundamental environmental alterations, such as new competitive market structures, governmental and regulatory changes, and technological progress, which often require managers to significantly adapt one or more aspects of their business models.’ | The number of aspects does not change the fact that the process is BMA. | Wirtz et al. (2010) [47] |

| ‘In each phase of the Business Model Adaptation process, firms emphasize different components of the business model, before they enter into continuous adjustments of all business model components. ‘ | Different phases of the BMA require the adaptation of different components. At the last phase of BMA, continuous adjustments of all components are required. | Landau et al. (2016) [9] |

| Changes in Business Model Components | Findings | Author |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Several studies characterize business model innovation as a continuous, evolutionary process, and emphasize the role of learning in business model innovation.’ | BMI is an evolutionary process. | (Landau et al., 2016) [9] |

| ‘Business model adaptation involves a process of continuous search, selection, and improvement in value creation, value proposition, and value capture, based on the surrounding environment.’ | BMA is a continuous process. | (Dopfer et al., 2017) [58] |

| Changes in Business Model Components | Findings | Author |

|---|---|---|

| ‘The process of adaptation appears to be either more highly motivated or more easily implemented in independent ventures than in established firms. ‘ | New companies are highly motivated to change their business model. | Chesbrough and Rosenbloom (2002) [28] |

| ‘Entrepreneurial firms are less constrained by path dependencies which makes them more flexible in designing more radical business models from scratch’ | Entrepreneurial firms design more radical BM. | Bohnsack et al. (2014) [53] |

| ‘Especially for new technology-based firms, defining an appropriate business model from the beginning is difficult, and adaptation of the initial business model is therefore crucial for success’ | BME is needed for start-ups. | Andries and Debackere (2006) [27] |

| ‘Companies tend to avoid major business model revisions (...) the focus on current profitable customers inhibits the exploration of emergent technologies in new commercial segments; in consequence, new business opportunities have often not been realized by incumbents, but by new ventures’ | A change of BM is more likely to be done by a start-up that by an incumbent. | Cavalcante et al. (2011) [60] |

| ‘A key success factor for emerging businesses of new ventures in turbulent and uncertain environments is therefore business model adaptation, characterized by rapid learning and adaptation to market changes’ | Adaptation is a key success factor for new businesses. | Dopfer et al. (2017) [58] |

| ‘(…) to reduce uncertainty about ecosystem participants’ needs, entrepreneurs can adapt their business model in an effort to better meet ecosystem needs ‘ | Adaptation is the way entrepreneurs evolve their business model to meet ecosystem needs. | Snihur et al. (2018) [10] |

| ‘In this study, we explore the connections between Business Model Adaptation and the success of new ventures’ ‘The ability to dynamically adjust the business model to changing environmental conditions and emerging market opportunities is a key capability expected to increase a start-up’s likelihood of survival in the short term and to support its growth in the medium and long term’ | BMA is a key factor for the success of new ventures. | Balboni and Bortoluzzi (2015) [63] |

| ‘We derived a model detailing the implications of different components of disruptive innovation and unveiling how incumbents can react through BMA.’ | BMA is the response of the incumbents to a disruptive innovation. | Cozzolino et al. (2018) [74] |

| Changes in Business Model Components | Findings | Author |

|---|---|---|

| ‘This is an important step as there is mounting evidence of multiple threats to utility firms which require long-term business model transition and adaptation to address’. | BMA is a long-term key success factor for well-established firms. | Wegner et al. (2017) [64] |

| ‘Firms have to innovate and adapt their business models to better fit the specific context of these international markets’. | BMA is a success factor when incumbents enter a new market. | Landau et al. (2016) [9] |

| ‘For established firms, BMI could be either the adaptation of its existing (core) business model or the development and introduction of a new business model adjacent to its core business’ | In established firms, BMA is a part of BMI. | Mezger (2014) [37] |

| Definition | Findings | Author |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Firms are increasingly confronted with fundamental environmental alterations, such as new competitive market structures, governmental and regulatory changes, and technological progress, which often require managers to significantly adapt one or more aspects of their business models.’ | BMA is the reaction to environmental changes such as market, regulations, and technological progress. | Wirtz et al. (2010) [47] |

| ‘Business Model Adaptation is a form of Business Model Innovation that addresses the development of a business model to better fit a new context’ | Adaptation can be sequential to step-by-step overcome the challenges of operating in an emerging market and to design a model that fits the new context. | Landau et al. (2016) [9] |

| ‘The process by which management actively innovates the business model to disrupt market conditions.’(…) ‘BMA is the reaction to a market change’ | BMI is a way to disrupt a market while BMA is the reaction of a market change. | Saebi et al. (2017) [7] |

| ‘Business Model Adaptation involves a process of continuous search, selection, and improvement in value creation, value proposition, and value capture, based on the surrounding environment.’ | BMA is based on the changes of the surrounding environment. | Dopfer et al. (2017) [58] |

| ‘While innovation, when attached to business models, is defined as the process by which firms actively innovate their business model to disrupt market conditions, the focus of this article is on how business models change in response to an external trigger. These changes have been defined as business model adaptation, that is, the process by which firms align their business model with a changing environment’ | BMI aims to disrupt a market while BMA is the process by which firms align their business model to changing environments. | Corbo et al. (2018) [16] |

| ‘The combination of low barriers to entry (for incumbents) and a robust, sizeable value pool, suggests adapting utility business models to capture this revenue would be an attractive option.’ | The perception of opportunities in a market can drive to BMA. | Wegner et al. (2017) [64] |

| ‘When companies succeed in the market with their business model and realize that there is further potential to expand, strategizing actions often lead to adaptations in the value creation logic.’ | The perception of opportunities and lead to BMA. | Achtenhagen et al. (2013) [23] |

| ‘Our main thesis of Business Model Adaptation is based on the premise that localization is necessary, and, therefore, firms need to adapt the models that are adopted from developed markets.’ | BMA firms need to adapt the models from developed markets to better fit local environments. | Sharma et al. (2016) [8] |

| Dynamic Capabilities | Findings | Author |

|---|---|---|

| ‘The dynamic capabilities framework appears to hold significant prospect for aiding the research into Business Model Adaptation and innovation.’ | BMA is a determinant of sustained superior performance in fast moving and high technology markets. | Dottore (2009) [1] |

| ‘If understood as part of a firm’s dynamic capabilities, the adaptation of the business model to a firm’s innovation activities assumes key strategic importance.’ | BMA can be understood as part of a firm’s dynamic capabilities. | Cavalcante et al. (2011) [60] |

| ‘We employ an activity-and capability-based view on what is needed to achieve business model change.’ | BMA can be analyzed from the lens of dynamic capabilities. | Achtenhagen et al. (2013) [23] |

| ‘The ability to dynamically adjust the business model to changing environmental conditions and emerging market opportunities is a key capability expected to increase a start-up’s likelihood of survival in the short term and to support its growth in the medium and long term.’ ‘The firms’ dynamic capabilities have been critical in keeping them alive and kicking in three highly dynamic business environments.’ | The dynamic adaptation of the business model acts as a driver of the success of the new venture. The authors analyze how three firms implemented BMA in an agile way. | Balboni and Bortoluzzi (2015) [63] |

| ‘Firms create a new business model by combining, integrating and leveraging internal resources with the capabilities and resources of the ecosystem’ | BMA depends on the internal resources as well as the capabilities and the resources of the ecosystem. | Sharma et al. (2016) [8] |

| BMA the Resource-Based View | Findings | Author |

|---|---|---|

| ’The activity system-based view addresses business model adaptations due to institutional factors and lack of external value creation partners.’ | This is a proper view to analyze BMA. | Landau et al. (2016) [9] |

| ‘Firms create a new business model by combining, integrating and leveraging internal resources with the capabilities and resources of the ecosystem’ | BMA depends on the internal resources as well as the capabilities and the resources of the ecosystem. | Sharma et al. (2016) [8] |

| ‘New ventures face huge challenges ‘as they adapt the business model based on limited resources in order to find the product-market fit’ ‘the venture needs to go through an iterative process of adaptation to achieve complementarity between business model components and a firm’s available resource base’ | BMA depends on the use of the limited resources of a company. | Dopfer et al. (2017) [58] |

| ‘Quantifying the relative size of the markets created and destroyed by energy transitions can provide useful insight into firm behavior and innovation policy’ | Resource-Based View is useful to understand a firm behavior when adapting its business model. | Wegner et al. (2017) [64] |

| Dimensions | Business Model Evolution | Business Model Adaptation | Business Model Innovation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Process or component | Component of BMI process | A process by itself but could be a form of BMI if innovative | A process by itself |

| 2 | Type of Business Model Change | Non-innovative & Innovative | Non innovative & Innovative | Innovative |

| 3 | If innovative, type of innovation | Incremental | Incremental & Radical | New BM and sometimes Radical |

| 4 | Magnitude of the changes | Few BM components are changed | Many components are changed | Many components are changed |

| 5 | Frequency of change | Continuous | Periodically | Infrequently |

| 6 | Type of companies that benefits from the process | All | All can, but incumbents could be more motivated | All can, but young companies could be more motivated |

| 7 | Attitude towards market disruption | Neutral | Victim of disruption | Seeks the disruption |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peñarroya-Farell, M.; Miralles, F. Business Model Dynamics from Interaction with Open Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 81. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/joitmc7010081

Peñarroya-Farell M, Miralles F. Business Model Dynamics from Interaction with Open Innovation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. 2021; 7(1):81. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/joitmc7010081

Chicago/Turabian StylePeñarroya-Farell, Montserrat, and Francesc Miralles. 2021. "Business Model Dynamics from Interaction with Open Innovation" Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 7, no. 1: 81. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/joitmc7010081