1. Introduction

Today, with the application of digital technology advancements—virtual and augmented reality, robots, and artificial intelligence—and the increasing use of various Internet and smartphone-related services, museums are changing and becoming ‘smart’. Digital technology, particularly, has enhanced, more than ever before, the existing potential value of museums’ cultural heritage and various contents beyond simple physical space and time constraints. Digitalisation improves the quality of the experience for visitors, makes museums accessible to more visitors, and promotes the use of the values and assets of museums in a wider variety of fields. In this respect, digitalisation is bringing about a new paradigm and an essential change in the relationship between museums and its users.

The trend of using digital media to convey information about museums’ collections has changed with time. Digital media was initially used for electronic brochures and digital metadata archives; however, since the 1960s, it has been used as an effective interactive tool for learning about museums, and this has led to using digital technology in conjunction with the exhibition sites of museums. For example, the Museum of Korean History combines an exhibition guide application with a QR code to provide information on collections accumulated in an on-site digital archive. Apps, such as ‘smarty’ from the National Gallery in London, play a similar role. While the data accumulated through such attempts have formed museum learning networks since the 2000s, the pandemic has provided an opportunity to showcase such information in an online space. For example, Korea’s National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art opened an online art museum in April 2020. This facilitated the process of the museum explaining information about the learning networks prepared in an online space through lectures by experts in related fields. Since a lot of information is provided from different perspectives—a docent tour-guide robot explains the various collections, museum educators or lecturers from universities speak on specific issues related to individual objects in the collection, and conservators present scientific information on new discoveries and the details of collections—it diversifies the perspective of viewing the collection, which in turn, stimulates the users’ historical imagination and complements their appreciation.

The importance of communication has always been emphasised in the context of museums. This has increased various interfaces for their content that act as contact points of communication with the development of digital technology. This leads to a richer and more memorable experience for visitors. With the diversification of communication methods, the increased frequency of online media use is changing the vulnerable generation’s perceptions of technology. This situation is creating further opportunities to change the relationship between museums and their users, and encouraging users to move up the hierarchy and engage proactively, thereby expanding the role of museums. Active participation of users in online communities is instrumental in influencing their engagement in museums and changing their roles. It influences visitors’ spatial and digital behaviours, and provokes associations with behaviours of new artists. Users also play a dominant role in shaping this content since their active participation changes their relationship with museums, and this change in their roles has become a crucial turning point of the museum industry. The rapid global spread of COVID-19 came as a shock to both public and private museums. It revealed the interests and structures of the cultural sector, and highlighted the increased role of online media. Additionally, it has hastened the digitalisation of museums by expanding the time and space of experience and knowledge, which in turn, increase user participation and change the relationship between museums and their users. Understanding this relationship will be important for the future of museums and for a competitive post-pandemic era.

In today’s rapidly changing environment, many studies on museum management have shown that museums facilitate communication with the public [

1,

2]; some have recommended using digitisation to promote communication about heritage [

3,

4], since it has the potential to impact various aspects of museums’ sustainability, social roles, and profitability [

5,

6]. However, existing studies refer only to technological and environmental changes that confront museums. They do not focus on the changes and challenges brought about by the pandemic, which will change the environment tremendously. Therefore, this study attempted to examine how museums will change after the pandemic, as well as their subsequent performance in securing sustainable competitiveness, by investigating the trends and future directions of their sustainable competitiveness in the rapidly changing post-pandemic environment. Additionally, while existing research focused on the relationship between museums and the artists as suppliers, this study focused on the relationship between museums and its users. To this end, it attempted to analyse the recent changes and trends in museums and reveal the direction in which they were headed.

2. Theoretical Discussion

Digital evolution has upgraded the way of life, more than it has done in the past [

7]. Digital technology not only promotes digesting vast amounts of information that could not be handled in the past, but also provides whole new experiences [

8]. While such changes bring many advantages, if not properly prepared, they may cause many social problems. Amid these social problems and changes, the role of museums is becoming more important, and there is an increasing need for them to constantly innovate and keep pace with such changes [

1]. From this point of view, museums play an essential role in cultural and social life. This may be possible because museums are powerful catalysts for ushering social changes in their communities. Furthermore, although museums are generally defined as non-profit permanent institutions, they contribute to the social economy. The number of visitors/users has a huge potential for the future growth of local communities, and, therefore, helps the sustainable management of museums [

9]. From this perspective, digital technologies are opening new dimensions of museums, as well as changing users’ experiences [

10,

11] and behaviours towards museums, which in turn are making new contributions to this industry. This situation is linked to ‘New Museology’—a new approach to museum practice based on critical thinking—that appeared at the end of the 1980s [

12]. It provides evidence of the cultural tastes of particular social groups and unfolds possibilities for the growth of users [

13]. It also makes a positive contribution to the national economy and supports sustainable well-being [

14,

15]. In this context, it may be useful to understand how the expansion of experience in the digital age creates new types of museums based on the transformation of relationship between their users.

2.1. Expansion of Experience in the Digital Age

Museums exhibit collections in physical space and create social discourses based on cultural diversity, following the collaboration of several stakeholders, such as the audience, conservators, curators, educators, and partners [

16]. Furthermore, museums contribute to social integration [

17]. In this respect, museums are a medium conveying culture; in other words, they are a mediator and facilitator of culture. Traditionally, museums, as a medium, exhibit their collections in a physical space, and the collections provide historical knowledge and aesthetic experiences for viewers [

18]. Various stakeholders collaborate to display their collections in exhibition halls and create a social discourse through diverse cultural expressions. Even when curators organise exhibitions, they focus on the appreciation of the collection and its interpretations [

19]. Traditionally, the exhibition hall is the medium in which the story of the museum begins. Therefore, the museum provides visitors with an interface, and its physical space is the mediator.

The COVID-19 pandemic has limited the existing physical interface of museums, and a whole new interface is required for people to have a museum experience. In this situation, the most important trend is digital. Due to the pandemic, many museums have closed their physical space. For example, Potts explains the J. Paul Getty Museum’s decision-making process during COVID-19 for the health and safety of both its staff and the public [

20]. As a result, museums have been looking for other channels to communicate with users [

17], and digital networks have emerged as a new interface for communication [

21]. Agostino investigated the reaction of the Italian museum during COVID-19, and found that the crisis triggers the openness of cultural messages and makes museums more interesting for online communications [

22]. Similarly, Simon provides a theoretical approach on how digital technologies are reshaping the museum value chain in an information environment, where boundaries between the offline and online worlds are becoming blurred [

23]. Manovich [

24] discussed new media’s reliance on the conventions of old media. Even if museums utilise new channels, e.g., the Internet, previous directions or forms would still affect the character of the new medium. In other words, the experience and knowledge of the collection shown in the exhibition space is reconstructed through digital media. Given that, the collections in exhibition halls are out of the original time and place context, there is little information that users are accustomed to understanding, and thus, museums should produce and convey knowledge about the collections. In this way, the knowledge gained by users helps them to appreciate the work. In the process of aiding exhibitions, museums have created a traditional value chain (communication structure) that conveys the explanations of the collections made by the producers to the users [

25]. In this respect, museums have tried to expand social discourse and provide information about their collections by using other media such as newspapers, radio, and TV [

26].

In the 1970s, as sustainable development became a societal issue, the concept of using museums as a tool to change society by intervening in social relations developed [

27]. In addition, the museum has been transformed into a place where members of society can exchange ideas and formulate opinions about society through the production of experiences and interpretations of collections, beyond information transmission [

28]. In this social context, the expectation that museums would change from an ‘old’ to a ‘new’ museology has shaped their exhibition functions. Supplementing this, the interrelationship of digital media plays an increasingly important role, in that it is easy for users to participate and manage. In this situation, Google Arts & Culture, which is considered to have been the most successful, has created a new channel through the Internet, emphasizing the active interpretation of viewers through virtual reality (VR) [

29]. Trunfion et al. [

30] recently analysed the effectiveness of AR and VR to enhance visitors’ experiences in cultural heritage museums. Many museums have participated in this online platform, and efforts have been made to convey knowledge and experiences. Samaroudi, Echavarria, and Perry surveyed the digital provisions and engagement opportunities of Memory Institutions in the UK and US during COVID-19, and explained their preferences related to content requiring digitisation from the audience’s perspective. This stands out in the fields of history and art [

31]. It complements the experience of the exhibition hall with an independent channel, and thus provides it with a different experience [

29]. The expansion of knowledge and experience using digital media is an innovation issue for museum managements involving user change [

32,

33]. Digitisation is essential for the expansion of experience and knowledge provided by museums [

34], and COVID-19 is accelerating this trend.

2.2. User Engagement

The service of the museum is completed through the user. The process of expanding knowledge and experience of the interface improves the quality of service and expands usage. From this point of view, a new interface (new media) beyond the existing exhibition space (old media) can be added to the existing service, so that more users can utilise it, contributing to stable management [

35]. In this regard, Manovich [

36] proposed the concept of ‘cultural interface’ by explaining the interaction pattern between humans and cultural data through computers. He investigated the characteristics of digital technology as enabling the ‘create, share, reuse, mix, create, manage, share and communicate content’ of messages [

24]. The museums’ new approach combined with social media beyond the existing exhibition space reinforces the user-centred environment, which is one of the advantages of new media. This is well coupled with participation programmes for social discourses that museums have been pursuing [

37]. This process is expected to contribute to the sustainability of museums as a result.

Museums have been transformed from spaces for people to spaces of people [

38]. The so-called ‘new museology’, which introduced a social education role for museums in the 1960s, developed it by means of various museums, such as community museums and open-air museums [

39,

40]. Based on McLuhan and Foire’s concept of media [

41], Glusberg and Benedit [

42] explained that the museum should become an intermediary that forms social discourse. The social functions of museums not only extend beyond economic benefits, but also contribute to social perspectives and reflect cultural democracy [

43]. Just as judiciaries can reduce the shadow economy or corruption if they deal with social interests independently [

28], museums can contribute towards social inclusion for similar social functions [

44]. This discussion suggests that the interests of museums have changed from ‘object-based epistemology’ to ‘object-based discourse’, and that the introduction of new technology has transformed the ‘object-centred museums’ into ‘experience-centred museums’ [

45]. Experience-oriented museums have become discovery spaces [

46]. Moreover, online museums expand user activities. Hence, museums linked to new digital technologies are highly likely to develop into user-centred spaces.

The open and interactive situation of new media also helps to expand the concept of a participatory museum [

47]. The openness and activeness created by new media increases the number of users and enhances the stable management of museums because it increases the opportunity for user participation. In this regard, Sutton emphasised that thoughtful approaches to engaging communities in collections, exhibitions and programmes could increase climate literacy and call people to action [

48]. Meanwhile, the development of the concept of a universal museum or a global museum in the era of globalisation is closely related to the tourism industry [

49,

50]. However, the number of museum users is decreasing due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the financial survival of museums is threatened. Magliacani and Sorrentino emphasised the value of communities in the economic dimension of sustainability and the importance of users’ variations [

51]. In this situation, museums’ use of new media plays an important role in retaining users, and is an effective tool to enhance their sustainability. Therefore, the COVID-19 pandemic is acting as a trigger for museums’ recent attempts to attract users, amid the changing social context. Furthermore, the solidarity of local communities using online media contributes to the sustainability of museums, in that it presents an opportunity to continuously expand the participants of museum management.

In the current situation, the challenge of museums is changing the long-term outlook of the museum industry, which will depend on how museums use the new interface. From this perspective, one of the most important points regarding new media for museums is whether it is possible to create a ‘constructivist museum’ of local communities through user-centred customisation and user participation [

52,

53]. Both concepts are well suited to the purpose of the museum as a space for social discourse. These changes in participation will determine the sustainability of the museum and are expected to accelerate, even after the COVID-19 pandemic. In light of these recent changes, user engagement in museum management and the resulting expansion of experience are expected to co-create value, and further achieve open innovation (see

Figure 1).

3. Research Design

The purpose of this study is to verify whether value co-creation based on user engagement and expansion of experience reflect the actual changes in museums. To answer this question, a case study methodology was applied. A case study is one of a variety of social science research methods, and is especially useful for explaining questions, such as ‘how’ and ‘why’, particularly when it is difficult for researchers to control events. When dealing with phenomena that occur simultaneously [

54], case studies are an essential research method in the social sciences [

55,

56]. This study employed multiple case studies. While the single-case study is often used when cases are very unusual or essential, multiple case studies have the advantage of being persuasive by comparing and analysing multiple cases to show a broader range of reality [

57]. As to how many multiple cases are appropriate, Yin [

54] argued that each case in a multi-case study can be regarded as one experiment in a broader survey or experiment; that is, by the logic of repeated studies, if the theory to be applied to the issue at hand is not very complex, then a small case analysis is considered sufficient.

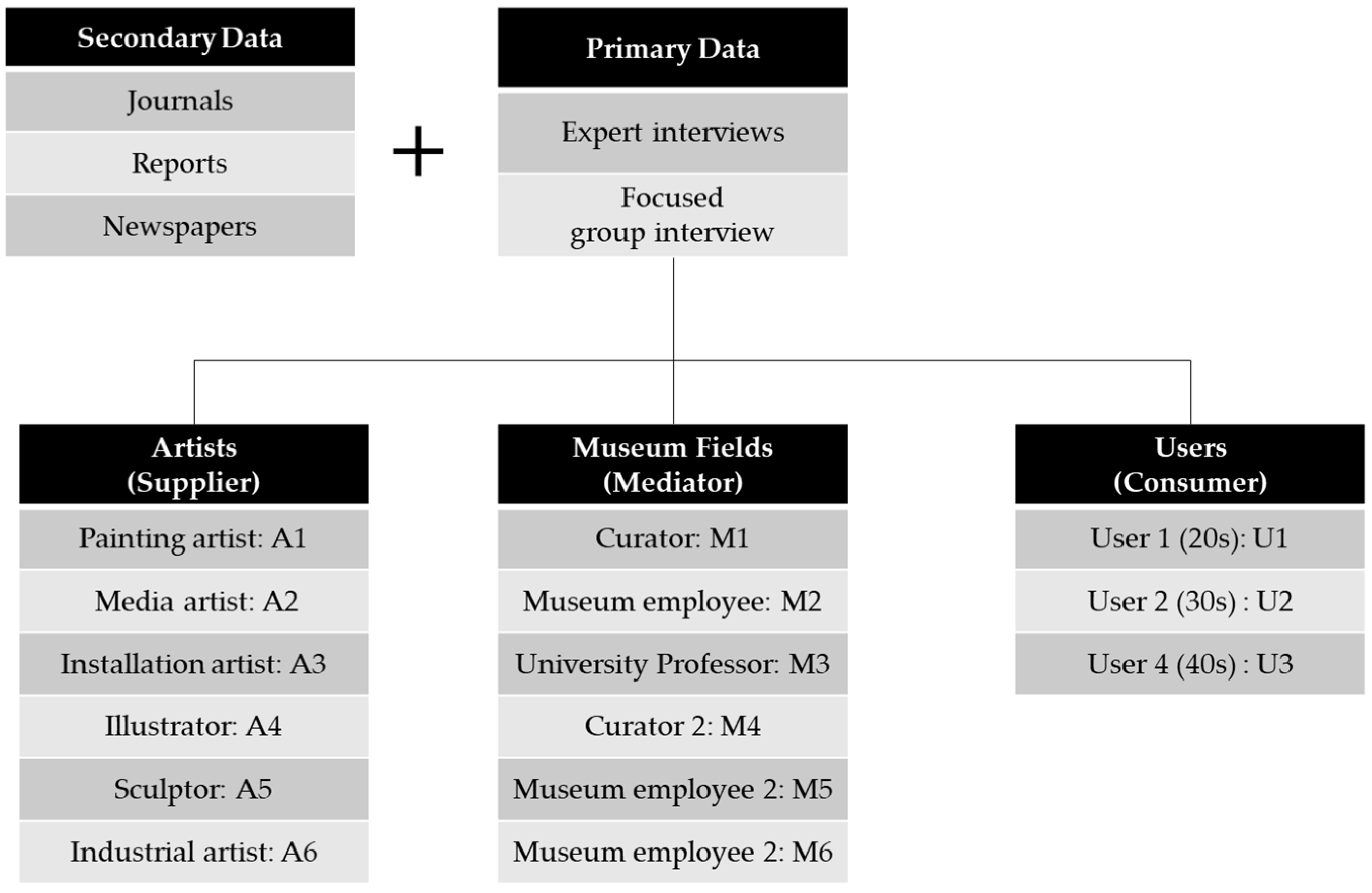

Therefore, this study aimed to examine whether the theoretically suggested classification and conceptual core elements can well explain the co-creation cases of various organisations. Looking at the cases of various successful companies was judged to be more appropriate. In this study, data were diversified (triangulation) to satisfy the widely accepted evaluation criteria proposed by Lincoln and Guba [

58] for qualitative research. It helped secure the study’s validity, and made it possible to increase the rigour by recording its entire process. In addition, in this study, data collection based on triangulation was conducted to increase its validity and generalisation. First, a theoretical framework was conceptualised based on existing studies and research. Then, secondary and primary data were collected, and based on the collected information, a pattern matching technique was used for comparison and analysis. Pattern matching analysis is a technique that compares and analyses the logic before data collection, that is, between the theory and the pattern that actually appears [

56,

59]. Then, in-depth interviews were conducted and snowball sampling was used to collect various opinions [

60]. A total of 15 research participants (6 artists, 6 museum employees and 3 consumers) were selected, as shown in the figure below. The subsequent research participants were recommended by them. Since it was felt that it would be desirable for the interviewees to freely talk about the subject and lead the discussion in a direction they considered meaningful, the in-depth interviews were conducted in the form of ‘conversations’ [

61,

62]. The greatest strength of conversational interviews is that they can capture the rich context of research topics. The in-depth interviews were conducted for 3 h to capture enough opinions from interviewees. Prior to the visit, interviewees, who had studied and familiarised themselves with significant art projects, were identified based on their profiles, and a questionnaire was compiled in advance to lead these semi-structured interviews.

In particular, to analyse the primary data, in-depth interviews (each lasting 2 h), were conducted with experts—three artists, three persons working in museums and related fields, and three users (see

Figure 2)—who had experienced the flow of change and understood museums (

Appendix A) using a semi-structured questionnaire (

Appendix B). Except for the users, each interviewee had at least 20 years of related experience. The criteria for selecting the interviewees were as follows. First, the relationship between existing museums and users was dealt with as the relationship between the person who creates exhibits, the museum that plans and provides services, and the users. In this situation, digital technology complements field-oriented services, and new changes related to the use of technology are changing the relationship between the stakeholders of museums.

The interviews were divided into three categories: suppliers, mediators, and users. Painters, new media artists, installation artists, sculptors, and industrial artists participated in interviews as suppliers. University professors, museum workers, art managers, and curators participated in the interviews as mediators in museum-related fields. To obtain opinions based on age, users were categorised as: in their 20s, 30s, and 40s. The focus group comprised of individuals from government, business, and academia, to gather their opinions. Data were collected by combining secondary data, documents, and 15 semi-structured interviews. Secondary data used for the systematic evaluation as part of the study took a variety of forms, including background papers, brochures, journals, event programmes, letters and memoranda, press releases, institutional reports, information available on museum websites, and scripts of an intervention at a conference about the project.

Qualitative research, such as case analysis, follows a different research method from quantitative research. Lincoln and Guba [

63] proposed criteria that qualitative studies can apply to ensure the suitability of the research method. In addition, Yin [

54] discussed criteria to verify the validity of the case analysis research method, especially among qualitative studies. This study additionally evaluated the construct validity and internal validity based on a study by Yin [

54]. The concepts—co-production and value-in-use—to be analysed in this study were derived from theories proposed by various preceding researchers, including Ranjan and Read [

64]. The cases were analysed from the research problem stage to their final results. Constitutive validity was satisfied. Meanwhile, internal validity can determine whether the causal relationship between the independent and dependent variables is well explained. The analysis of empirical data was based on continuous comparative analysis or ’coding’. The entire data set was read, the data were split into smaller meaningful parts, then each chunk was labelled with a descriptive title (or code) and similar pieces. Coding was mainly undertaken a priori because the code was identified before the analysis (as reflected in the conceptual framework) and then looked up in the data.

4. Findings

4.1. User Direct Engagement

Museums are experiencing a digital transformation, and changes in the external environment caused by the COVID-19 pandemic are altering the way they operate. According to the Korea National Culture and Arts Survey’s statistics, the attendance rate of culture and art in 2020 was 60.5% (down 21.3% from 2019) [

65]. Efforts have been made to overcome the situation caused by the pandemic, and museums have begun to utilise digital technology more than in the past. This is because the COVID-19 conditions entail the use of computer technology to enable museums to play the roles of partners, colleagues, learners, and service providers. The knowledge and experiences provided by museums are being extended through the openness, connectivity, and mobility of the Internet environment. The development of digital technology makes it possible for users to directly engage with museums. The trend of museums using digital media to convey information about their collections has changed with the times. Initially, digital media was used as an electronic brochure and digital metadata archive. After the 1960s, it began to be used as an effective tool for learning about museums with interactivity. This has led to the use of digital technology combined with the museums’ exhibition sites. For example, the Museum of Korean History combines an exhibition guide application with a QR code, to provide information on collections accumulated in a digital archive on-site. Museums’ interests are in showing visitors not only collections, but also encouraging interactions with users.

Apps, such as smarty from the National Gallery in London, play the same role. Since the 2000s, the data accumulated through such attempts have formed museum learning networks. The COVID-19 pandemic has created an opportunity to showcase information about such knowledge in an online space. The National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Korea, for example, opened an online art museum in April 2020.

In particular, smart devices and online platforms were used more at art exhibitions than in other fields among ‘media used to watch cultural and artistic events’, according to Korea’s National Culture and Arts Survey, 2020 (See

Table 1).

In the process, museums explain information about the learning networks prepared so far in an online space through lectures by related experts. A docent tour-guide robot explains the work, museum educators or lecturers from universities speak on specific issues to explain the collection, and a conservator presents scientific information about new discoveries and details of the work. This direct engagement of users explains a lot of information from different perspectives and diversifies the perspective of viewing the collection, which stimulates users’ historical imagination and complements their appreciation. Short and insightful conversations, involving people with considerable experience in the field, attract more visitors, build better relationships, and improve the use of technology to open up museums’ products. M3 explained,

“Even though online art museums are not the same as on-site experiences, the process of knowledge transfer through online art museums can certainly reduce the psychological distance of viewers to the collection, and create new cultural values. As users’ direct engagement becomes possible, more diversified value is created.”

It is not the same experience as on-site, but allows museums to understand visitors because of their participation beyond the limits of time. The growing opinions of users provide a variety of usefulness for museum’s contents to other users. More diversified opinions make it easy for users to offer their own views. M2 stresses that the way the museum views users will change rapidly due to COVID-19.

“With the transition from Web 1.0 to Web 2.0, user participation is becoming more important. The growth of museums was relatively slow. However, there has been a growing movement in recent years based on the belief that museums will not be competitive without communication and engagement with users. […] In particular, with COVID-19 increasing the importance of digital, the degree of engagement with users will be directly linked to museums’ competitiveness.”

M5 emphasises that the COVID-19 crisis presents an opportunity to innovate around the museums’ activities for users.

“The pandemic is making the dimension of visitor behaviour more complex because limited personal experiences during the pandemic increase the desire for conversations. A museum is a place where visitors explore and/or maintain particular aspects of their identity through the communication of other visitors’ experiences. These social needs, attitudes, and values influence the direction of technology used to overcome personal isolation in these days and becomes the energy for museum innovation.”

Fewer opportunities to meet in the real space in the situation of pandemics increase the desire for communication with others. It encourages more participation of users on online platforms, and differentiates the social discourses on museums. This leads to innovation, in that it makes museums find more useful and effective ways to communicate with their users. M5′s opinion shows why online platforms are used more actively in the pandemic for the direct engagement of users.

4.2. Value Co-Creation

Museums have recently been transformed into user-centred institutions. Based on the ubiquitous environment, the number of users who can easily access museums with a smartphone or digital device is increasing, making it easy to access museum content. In this way, museums have begun to provide content that users can choose for themselves, which means that museums offer users partly shared responsibilities and interchangeable roles. Furthermore, users start to create value jointly. The National Museum of Korea has been encouraging viewers to devise their own digital paths through a tablet provided through the information centre, which has led to the introduction of artificial intelligence docent robots. This choice by the museum changed viewers’ experiences in various ways. The Korean History Museum encourages visitors to input their opinions after viewing an exhibition, and in so doing, makes them aware of the thoughts and opinions of other viewers. The process of developing into a museum that makes use of social media is used as a basis for creating an open social discourse by opening information and inducing interests through comparing users’ perspectives. Thus, the concept of users started to change from consumers to value co-creators. These new tendencies illustrate that museums desire to delegate their authority to the users. As a result, museum experts become managers of users’ activities. M2 explained that these changes were necessary and played a role in lowering the entry barrier to museums.

“Unlike having to go to a place in an art gallery, now, we are using platforms like YouTube and Instagram. Institutions have to use them for their promotion, and if they do not, it will not be easy for them to promote themselves. I think of it as a sharing platform, and this lowers the entry barrier to museums. This lowered barrier encourages more users to participate in museums’ value creation together.”

M1 referred to the characteristics of online media and explained the reason for developing user-oriented services.

“

According to Nina Simon [47], the role of users is increasing. Social media moves information and expands discourse. Considering that the purpose of museums is to expand social discourse, the effects of sharing experiences and derivatives through connectivity are positive factors. The basis of this situation is the diversity of experiences, which comes from the choices of users. Thus, I think museums are interested in providing user-centred services that enable users to create value together.”

According to A2, this differentiates users and combines them with their social community. In other words, to expand social discussions, the museum as a mediator creates a user-centred programme, which promotes the differentiation of spectators’ communities, based on their perspective on collections and on openness. In this way, museums use social relationships as their primary medium. U3 explained that as users’ participation increases, the process of creating common value would accelerate beyond the limitations of existing intermediaries.

“Museums are now moving from being a provider to providing a platform. They create the role of a mediator in the process of constructing and creating meaning through user-centred programmes. The inclusion of users in museum services changes the concept of the museum itself, and gives it a new social role.”

User-centred programmes with user-participation change the view of the museum system, and traditional museums centred on collections are transformed into museums centred on social relations. It is highly effective in motivating users and making them protagonists. Such user-centred services differentiate the viewpoint of museums and expand the diversified experiences of users. It creates museums based on social relations and the spread of new museums aimed at creating common value. This expands value co-creation among users and museums.

4.3. Connecting Museums

As users’ participation increased, the connectivity of museums also increased. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic seems to have emphasised this role for the survival of museums. For example, after the pandemic started, the Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture provided new opportunities for communication to media artists and citizen creators, who were previously working on online platforms through the ‘Art Must Go On’ project. This programme is intended to give users with different occupations the possibility of exhibiting, thereby encouraging users’ participation during the pandemic. The exhibition development responsibility is shared among multiple players.

The Seoul Museum of Art, SeMA Storage, has been planning exhibitions by running the ‘Art Exhibitions Made by Citizens’ programme (See

Figure 3)—a kind of experimental laboratory—that allows museums to use community resources. Ten exhibitions are organised by educating a large number of citizens, and ten people are selected from amongst graduates, who have completed an education programme, through an exhibition planning contest. They are provided with exhibition grants, advice, and practical workshops, and have access to online exhibitions through museums’ YouTube channels. This project has a higher participation rate than other educational programmes. Currently, six exhibitions have been held, and strong interest has been maintained even after the initial outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Such programmes have become the most important online programmes offered by the Seoul Museum of Art in the post-COVID-19 era. Connecting museums to communities means, above all, to cooperate. Cooperation is a means of developing new audiences, generating additional types of relationships with its audience, and exploring other ideas. One user’s participation is through Seoul’s Media Canvas, which uses videos to display works through an electric sign in Seoul Square, and has not been highly affected by the pandemic (See

Figure 4).

M1, who was in charge of this programme, described it as follows.

“The Seoul metropolitan government operates the Media Canvas. In this case, citizens can also produce works, so citizen creators and professional artists exhibit together. The degree of understanding would be different, but the process increases access to digital technology. Citizens can present ideas and speak up more about creative works. […] This lowers the entry barrier.”

Users playing the role of producers or intermediaries through participation integrates the existing producer–intermediary–user relationship and lowers the barrier to entry of museums as intermediaries. The direct participation of users changes the environment of museums, a point explained by the position of supplier A3:

‘In the case of digital media, users who create something new by utilizing the characteristics of the medium will emerge’. In the case of Seoul’s Media Canvas, the direct participation of users makes it possible for them to become producers. This position is not the same as that of an artist, who is a professional producer, but it can convey a more creative message, in that, the profession is different. It is because each work is an individual expression and citizen creators have a different purpose from professional artists. Users’ participation, which is different from existing producers, mediates various areas in a complex manner and gives a fusion characteristic. Most users of these programmes belong to the local community. According to the statistics of Korea’s National Culture and Arts Survey in 2020, the percentage of participants in cultural and artistic events, from their residences was 85.4% [

65].

The user’s role as a producer or intermediary improves the relationship between the museum and the local community. In this situation, producers, intermediaries, and users have no choice but to collaborate, and in this process, the role of the intermediary changes. M3 explained this as follows.

“For me, while dealing with public art programmes, it is crucial to consider the position of participants. Existing writers have to expand their thinking. […] It is necessary to meet architects of different genres, and it also emphasises the role of connecting painting writers with media engineers. […] However, collaboration with citizens is also an important part. In some cases, citizens are both initiators and producers, as well as writers are producers, but they become intermediaries (through collaboration). Curators create a big framework (for communication) as mediators, but they also act as initiators and helpful linkers in the system.”

Museums that have conducted programmes, such that users can play the role of intermediaries, will play a role in connecting and coordinating various stakeholders, and are differentiated from existing museums that deliver messages. This process inevitably emphasises the identity of the local community, in that it connects producers (artists) and users in the areas where the museums are located. The collaborating museum improves its capacity for survival, in that it strengthens the identity of the collaborators and creates a core group that includes users. Direct user participation reinforces the identity of the local community by producing a discourse. Moreover, this process integrates the relationship between producers, mediators, and users through collaboration and mediation, and has a fusion characteristic. Users can be converted into producers in some cases, which increases the possibility of production and mediation of creative messages. This represents a break from the role of an intermediary who conveys the message of existing museums, connects and coordinates stakeholders, and increases the chances of survival through external stakeholders. A new type of museum different from the traditional museum is being created. The museum, as a platform, is an important medium through which a community can take control of museum products. Socially responsible work is also a shared responsibility. Through interchangeable role-playing, participants become agents of change, as against the ‘bottom-up’ approach. It differentiates the communication channels and invites more visitors to museums. This transformation of differentiated cultural channels also contributes to cultural diversity, one of the most important goals of the World Decade for Cultural Development (1988–1997), and of the Future Cultural Strategy 2020 of the Korea Culture & Tourism Policy Institute [

67,

68].

4.4. Network Effects

The quality of the content is higher than before, owing to the need for education required for handling such information. Additionally, the network effect is explosively increased due to the number of users. This situation is leading to users’ interest in education through the connectivity, openness, and mobility of online media. Furthermore, users create a community of viewers. Interviewee U2 stated:

“I used to go to museums or art galleries with my friends and participate in events because there is a lot of interesting content. Thus, when I became a parent, I thought it was useful to my children, so I went with them. Owing to COVID-19, we sometimes show museum content to children and watch online events together. Online is strengthening, and I see people with similar interests as mine, and in some cases, I have conversations with other users, and such conversations seem to create more value with each other.”

In the process of expanding knowledge and services with the advent of online art museums, the participation of experts who demonstrate perspective through data connections, rather than viewing data, increases the level of education, but further strengthens communication between intermediaries and users. This helps to activate users’ interest in education, and the community of users who share this information. The perspectives of U1 and U2 show that museums can provide entertaining content, and their elements get more people involved and make users more active.

The expansion of knowledge of museums enhances users’ immersion. This helps users to appreciate works, through an attempt to deliver knowledge, while providing pleasure, based on the museum’s learning network. This is confirmed by the fact that the British Museum is currently conducting a school education programme, through virtual space from a distance, through collaboration with Samsung. As a result of flip learning in the field of education, the use and participation of visual information due to online content improves viewers’ memories of museums and consequently, the museum is shared more as a social platform. As Bourdieu [

69] mentioned, visitors with prior experience are highly likely to re-visit museums. The use of online media has previously shifted from unilateral information delivery to active education. In particular, COVID-19 is strengthening the perspective of museums using data retrieval, through linking, opening, moving, and expanding information.

In this regard, M6 explains:

“Just as listening to a story changes your own views, seeing works presented by other participants in the museum platform makes other users more active. Museum programmes based on participation contribute to their sustainable development. […] I believe that the imagination of participating users will play an important role in the activities of museums because it stimulates other users’ imagination. It helps all of them formulate their own understanding and it is possible to derive positive results from the museum products themselves. The value to individual users increases as more users use it.”

The reinforcement of users’ communities stimulates their activeness, alongside the enjoyment of using education and entertainment in museums. This is because users also have the opportunity to observe and evaluate other users, rather than just looking at their collections through the museums’ communication channels. This improves the quality of users’ appreciation of the collections and raises interest in them, contributing to the sustainability of museums. As the number of users participating in the museum increases, the utility gained from consuming the product increases, and this is directly related to the competitiveness of museums.

5. Conclusions

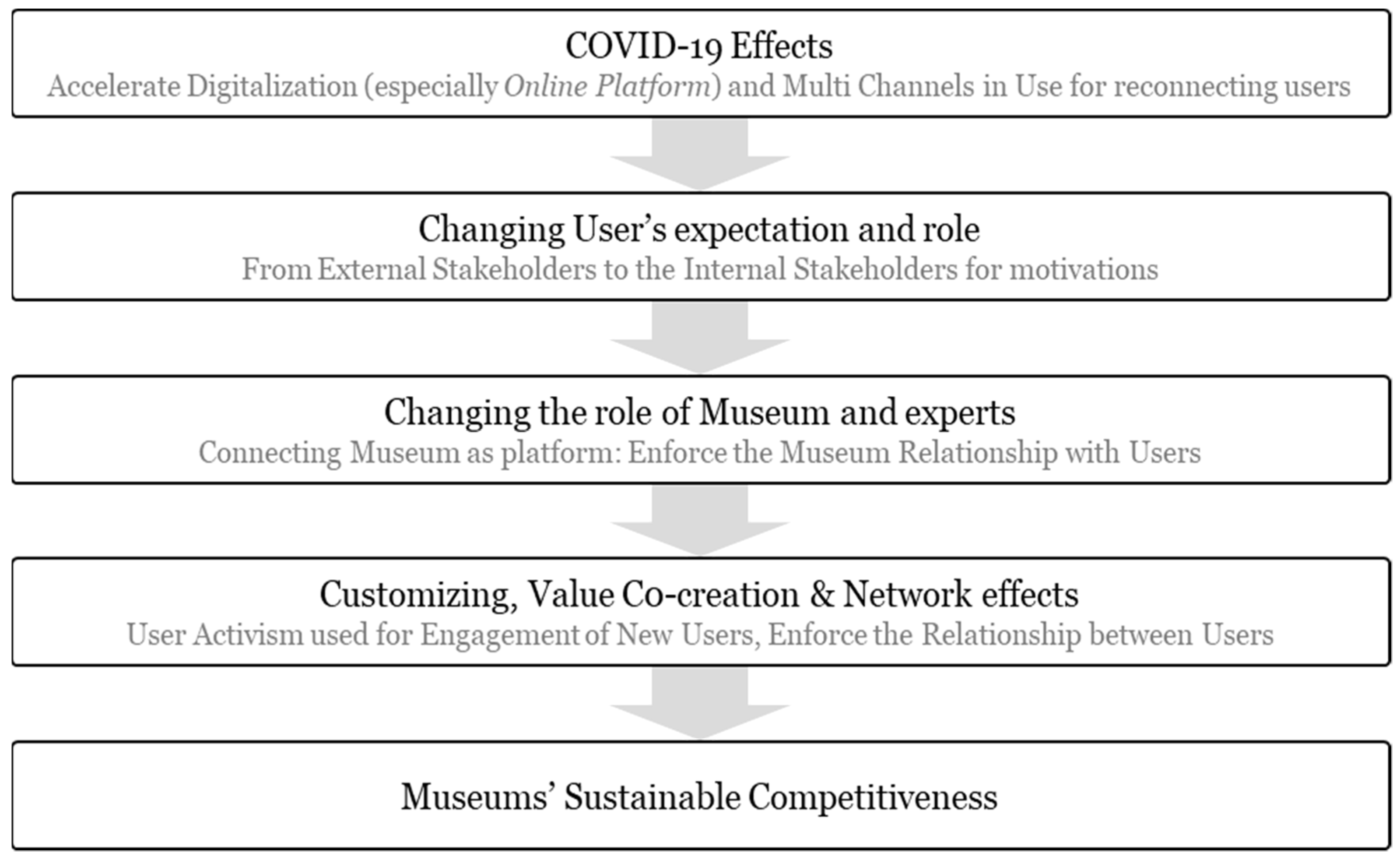

The COVID-19 pandemic led to the decline of visitors to museums and caused widespread damage to the Museum industry. Consequently, to overcome difficulties and such unexpected threats, museums have had to adapt and incorporate diversified strategies. Recently, it has been observed that museums use a wide range of communication channels, more than they did in the past, and beyond the limits of face-to-face communication at physical spaces, such as exhibitions. In light of the social situation, the Internet provides museums with a new communication channel—online multimedia platforms. Since museums are planning programmes in which an increased number of users can participate compared to traditional museums, digital platforms or sharing platforms, similar to Google, for museums have emerged. As already mentioned, in the Seoul Museum of Art, users are able to replace the role of the curator. As in the case of the Seoul Media Canvas, users act like artists. Users, who were existing observers in the traditional value chains, are now involved with museums’ project work as internal stakeholders, and their behaviours and expectations have changed.

In this way, it can be noticed that the method of linking the museums’ resources, that is, reinforcing the role of museums by mixing intangible resources in various ways, frees museums from their previous rigidity, as the degree of blending increases. It goes beyond the idea of providing information and managing users in traditional museums, and uses the digital interface as a new communication channel. In connection with this, we can find that visitors who traditionally belonged to the museum’s external stakeholders began to act as internal stakeholders. User participation or involvement in the products of museums and visitor experiences, replaces experts, who previously performed this role, and also engages other users. While museums previously made visitors experience products by communicating with target users and played a role in managing their opinions, in the future, museums will co-create new museum products along with visitors. In other words, users will become producers and consumers at the same time. As part of the larger digital supply chain, museums are positioned to transform user relationships and stabilise the museum industry as active supporters; consequently, museums could expand social discourse boundaries and issues. This can be seen as an attempt to retain and create existing users while enhancing the museums’ capacity and making them more visible in the social context.

With the close cooperation between museums and its users, the value of such connections becomes more critical. Participants in a museum’s product production process, who know the museum well, could become active in promoting other users, in that they produced it. Additionally, the differentiation of social discourse through users’ perspectives changes the museum as a platform for communication and contributes to social integration. From an economic point of view, they specifically play a positive role as concrete supporters of the museum. Participants influence not only other users on the museum’s online platform, but also motivate actual visits to the museum, and serve as a positive factor for the influx of new users. This change increases the number of connections between users, resulting in network effects, leading to an improved experience as more people participate in the museums’ activities, thereby changing their ecosystem. It affects other users through transactions and communication. As the relationship between users becomes more diversified and dispersed, the number of users of the museum increases and the museum’s value changes positively, which supports its sustainable development. In the process of collaboration, the decentralisation of museum authority and the production of users’ contents, diversify the communication channels surrounding the museum, which stabilises its sustainability. As a result, good connections between different users and their social support can improve the social framework. They try to attentively understand the museums’ products and communicate effectively with others, which in turn, creates social discourse through a mix of community opinions.

The COVID-19 pandemic is changing our world, and in some ways, it looks set to become better and more positive through innovation. Museums are now expanding their role from suppliers to social relationships platforms, using digital technologies and opening their positions to the public. In response, after COVID-19, museums should focus on managing the co-creation of value in the first place, because it is one of the most effective solutions for their sustainable development amidst the challenges in the COVID-19 epoch and thereafter (See

Figure 5). As the COVID-19 pandemic abates, museums will certainly be changing in different ways, affecting not only the exhibition, but also the way visitors participate and communicate. It will no doubt change the relationship between the museum and its visitors. Therefore, museums need to respond well to these changes. This study has limitations because it only deals with Korean cases. Therefore, future studies should plan to compare the current status of museums in other countries, and through this, a more advanced study can be expected.