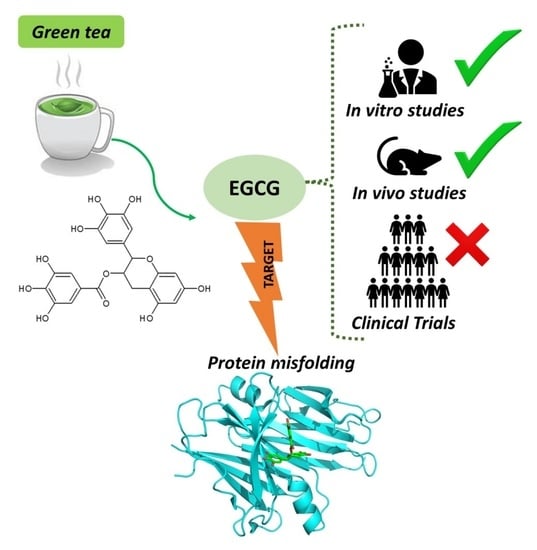

Green Tea Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) Targeting Protein Misfolding in Drug Discovery for Neurodegenerative Diseases

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Neurodegenerative Diseases

2.1. Alzheimer’s Disease

2.2. Parkinson’s Disease

2.3. Neurodegenerative Drug Discovery

2.4. Natural Products against Neurodegeneration

3. Protein Misfolding in Neurodegenerative Diseases

3.1. Misfolded Aβ in AD

3.2. Misfolded α-Syn in PD

4. EGCG for Treating Neurodegenerative Diseases

4.1. Evidence from In Vitro Neurotoxicity Models

4.2. Evidence from Animal Models

4.3. Evidence from Clinical Trials

5. EGCG Targeting Misfolded Aggregates in AD and PD

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dorsey, E.R.; Elbaz, A.; Nichols, E.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; Adsuar, J.C.; Ansha, M.G.; Brayne, C.; Choi, J.Y.J.; Collado-Mateo, D.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of Parkinson’s disease, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 939–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nichols, E.; Szoeke, C.E.I.; Vollset, S.E.; Abbasi, N.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdela, J.; Aichour, M.T.E.; Akinyemi, R.O.; Alahdab, F.; Asgedom, S.W.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- 2020 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2020, 16, 391–460. [CrossRef]

- Yacoubian, T.A. Neurodegenerative Disorders: Why Do We Need New Therapies? Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; ISBN 9780128028117. [Google Scholar]

- Gribkoff, V.K.; Kaczmarek, L.K. The need for new approaches in CNS drug discovery: Why drugs have failed, and what can be done to improve outcomes. Neuropharmacology 2017, 120, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Koeberle, A.; Werz, O. Multi-target approach for natural products in inflammation. Drug Discov. Today 2014, 19, 1871–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.T.; Tran, Q.T.; Chai, C.L. The polypharmacology of natural products. Future Med. Chem. 2018, 10, 1361–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, P.B.; Romeiro, N.C. Multi-target natural products as alternatives against oxidative stress in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 163, 911–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.; Silva, R.; Pinto, M.M.M.; Sousa, E. Marine natural products, multitarget therapy and repurposed agents in Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.A.; Mandal, A.K.A.; Khan, Z.A. Potential neuroprotective properties of epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG). Nutr. J. 2016, 15, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cascella, M.; Bimonte, S.; Muzio, M.R.; Schiavone, V.; Cuomo, A. The efficacy of Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (green tea) in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: An overview of pre-clinical studies and translational perspectives in clinical practice. Infect. Agent. Cancer 2017, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, A.; Sarkar, J.; Chakraborti, T.; Pramanik, P.K.; Chakraborti, S. Protective role of epigallocatechin-3-gallate in health and disease: A perspective. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 78, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhu, Q.; Chen, J.Y.; OuYang, D.; Lu, J.H. The pharmacological activity of epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) on Alzheimer’s disease animal model: A systematic review. Phytomedicine 2020, 79, 153316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadakkan, K.I. Neurodegenerative disorders share common features of “loss of function” states of a proposed mechanism of nervous system functions. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 83, 412–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugger, B.N.; Dickson, D.W. Pathology of neurodegenerative diseases. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomier, K.M.; Ahmed, R.; Melacini, G. Catechins as tools to understand the molecular basis of neurodegeneration. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, P.; Park, H.; Baumann, M.; Dunlop, J.; Frydman, J.; Kopito, R.; McCampbell, A.; Leblanc, G.; Venkateswaran, A.; Nurmi, A.; et al. Protein misfolding in neurodegenerative diseases: Implications and strategies. Transl. Neurodegener. 2017, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iadanza, M.G.; Jackson, M.P.; Hewitt, E.W.; Ranson, N.A.; Radford, S.E. A new era for understanding amyloid structures and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 755–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scannevin, R.H. Therapeutic strategies for targeting neurodegenerative protein misfolding disorders. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2018, 44, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaman, M.; Wahiduzzaman; Khan, A.N.; Zakariya, S.M.; Khan, R.H. Protein misfolding, aggregation and mechanism of amyloid cytotoxicity: An overview and therapeutic strategies to inhibit aggregation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 134, 1022–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, C.; Pritzkow, S. Protein misfolding, aggregation, and conformational strains in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 1332–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lázaro, D.F.; Bellucci, A.; Brundin, P.; Outeiro, T.F. Editorial: Protein Misfolding and Spreading Pathology in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2020, 12, 2019–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ritchie, D.L.; Barria, M.A. Prion diseases: A unique transmissible agent or a model for neurodegenerative diseases? Biomolecules 2021, 11, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, C. Unfolding the role of protein misfolding in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2003, 4, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrnhoefer, D.E.; Duennwald, M.; Markovic, P.; Wacker, J.L.; Engemann, S.; Roark, M.; Legleiter, J.; Marsh, J.L.; Thompson, L.M.; Lindquist, S.; et al. Green tea (-)-epigallocatechin-gallate modulates early events in huntingtin misfolding and reduces toxicity in Huntington’s disease models. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006, 15, 2743–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrnhoefer, D.E.; Bieschke, J.; Boeddrich, A.; Herbst, M.; Masino, L.; Lurz, R.; Engemann, S.; Pastore, A.; Wanker, E.E. EGCG redirects amyloidogenic polypeptides into unstructured, off-pathway oligomers. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008, 15, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, N.; Cardoso, I.; Domingues, M.R.; Vitorino, R.; Bastos, M.; Bai, G.; Saraiva, M.J.; Almeida, M.R. Binding of epigallocatechin-3-gallate to transthyretin modulates its amyloidogenicity. FEBS Lett. 2009, 583, 3569–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sonawane, S.K.; Chidambaram, H.; Boral, D.; Gorantla, N.V.; Balmik, A.A.; Dangi, A.; Ramasamy, S.; Marelli, U.K.; Chinnathambi, S. EGCG impedes human Tau aggregation and interacts with Tau. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkkinen, M.G.; Kim, M.O.; Geschwind, M.D. Clinical neurology and epidemiology of the major neurodegenerative diseases. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2018, 10, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vaupel, J.W. Biodemography of human ageing. Nature 2010, 464, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beard, J.R.; Officer, A.; De Carvalho, I.A.; Sadana, R.; Pot, A.M.; Michel, J.P.; Lloyd-Sherlock, P.; Epping-Jordan, J.E.; Peeters, G.M.E.E.; Mahanani, W.R.; et al. The World report on ageing and health: A policy framework for healthy ageing. Lancet 2016, 387, 2145–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hou, Y.; Dan, X.; Babbar, M.; Wei, Y.; Hasselbalch, S.G.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. Ageing as a risk factor for neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 15, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sami, N.; Rahman, S.; Kumar, V.; Zaidi, S.; Islam, A.; Ali, S.; Ahmad, F.; Hassan, M.I. Protein aggregation, misfolding and consequential human neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Neurosci. 2017, 127, 1047–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mroczko, B.; Groblewska, M.; Litman-Zawadzka, A. The role of protein misfolding and tau oligomers (TauOs) in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mehra, S.; Sahay, S.; Maji, S.K. α-Synuclein misfolding and aggregation: Implications in Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Proteins Proteomics 2019, 1867, 890–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.; Bharathi, V.; Sivalingam, V.; Girdhar, A.; Patel, B.K. Molecular mechanisms of TDP-43 misfolding and pathology in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2019, 12, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheckel, C.; Aguzzi, A. Prions, prionoids and protein misfolding disorders. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 19, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, T.; Ziegler, A.C.; Dimitrion, P.; Zuo, L. Oxidative Stress in Neurodegenerative Diseases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Applications. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Kukreti, R.; Saso, L.; Kukreti, S. Oxidative stress: A key modulator in neurodegenerative diseases. Molecules 2019, 24, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cenini, G.; Lloret, A.; Cascella, R. Oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases: From a mitochondrial point of viewCenini, G., Lloret, A.; Cascella, R. Oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases: From a mitochondrial point of view. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Guzman-Martinez, L.; Maccioni, R.B.; Andrade, V.; Navarrete, L.P.; Pastor, M.G.; Ramos-Escobar, N. Neuroinflammation as a common feature of neurodegenerative disorders. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, A.; Sun, H.; Han, Y.; Kong, L.; Wang, X. Two decades of new drug discovery and development for Alzheimer’s disease. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 6046–6058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gabr, M.T.; Yahiaoui, S. Multitarget Therapeutics for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biomed Res. Int. 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsay, R.R.; Popovic-Nikolic, M.R.; Nikolic, K.; Uliassi, E.; Bolognesi, M.L. A perspective on multi-target drug discovery and design for complex diseases. Clin. Transl. Med. 2018, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Benchekroun, M.; Maramai, S. Multitarget-directed ligands for neurodegenerative diseases: Real opportunity or blurry mirage? Future Med. Chem. 2019, 11, 261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maramai, S.; Benchekroun, M.; Gabr, M.T.; Yahiaoui, S. Multitarget Therapeutic Strategies for Alzheimer’s Disease: Review on Emerging Target Combinations. Biomed Res. Int. 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Freschi, M.; Nascente, L.D.C.; Salerno, A.; de Melo, S.; Teixeira, V.; Nachon, F.; Chantegreil, F.; Soukup, O.; Malaguti, M.; et al. Sustainable Drug Discovery of Multi-Target-Directed Ligands for Alzheimer ’ s Disease. J. Med. Chem. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization WHO - The top 10 causes of death. Available online: http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death (accessed on 6 January 2021).

- Du, X.; Wang, X.; Geng, M. Alzheimer’s disease hypothesis and related therapies. Transl. Neurodegener. 2018, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cummings, J.; Lee, G.; Ritter, A.; Sabbagh, M.; Zhong, K. Alzheimer’s disease drug development pipeline: 2020. Alzheimer’s Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2020, 6, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, P.V.; Steadman, D.; Bayle, E.D.; Whiting, P. New approaches for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 29, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sun, G.; Feng, T.; Zhang, J.; Huang, X.; Wang, T.; Xie, Z.; Chu, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, H.; et al. Sodium oligomannate therapeutically remodels gut microbiota and suppresses gut bacterial amino acids-shaped neuroinflammation to inhibit Alzheimer’s disease progression. Cell Res. 2019, 29, 787–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, Y.Y. Sodium Oligomannate: First Approval. Drugs 2020, 80, 441–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masters, C.L.; Bateman, R.; Blennow, K.; Rowe, C.C.; Sperling, R.A.; Cummings, J.L. Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2015, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, C.A.; Hardy, J.; Schott, J.M. Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 2018, 25, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, G.S. Amyloid-β and tau: The trigger and bullet in Alzheimer disease pathogenesis. JAMA Neurol. 2014, 71, 505–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Busche, M.A.; Hyman, B.T. Synergy between amyloid-β and tau in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 1183–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundke-Iqbal, I.; Iqbal, K.; Tung, Y.C. Abnormal phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein τ (tau) in Alzheimer cytoskeletal pathology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1986, 83, 44913–44917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goedert, M. Tau protein and the neurofibrillary pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Neurosci. 1993, 16, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, R.H.; Nagao, T.; Gouras, G.K. Plaque formation and the intraneuronal accumulation of β-amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease. Pathol. Int. 2017, 67, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, A.B.; Arain, H.A.; Stecker, M.M.; Siegart, N.M.; Kasselman, L.J. Amyloid toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Rev. Neurosci. 2018, 29, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, J.A.; Higgins, G.A.; Hardy, J.A.; Higgins, G.A. Alzheimer ’ s Disease: The Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis Published by: American Association for the Advancement of Science Alzheimer ’ s Disease: The Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis. Science 1992, 256, 184–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejanin, A.; Schonhaut, D.R.; La Joie, R.; Kramer, J.H.; Baker, S.L.; Sosa, N.; Ayakta, N.; Cantwell, A.; Janabi, M.; Lauriola, M.; et al. Tau pathology and neurodegeneration contribute to cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2017, 140, 3286–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mullard, A. BACE failures lower AD expectations, again. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullard, A. News in Brief: Innovative antidepressants arrive; Anti-amyloid failures stack up as Alzheimer antibody flops. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Panza, F.; Lozupone, M.; Logroscino, G.; Imbimbo, B.P. A critical appraisal of amyloid-β-targeting therapies for Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 15, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Muñoz, M.J.; Castillo-Carranza, D.L.; Kayed, R. Therapeutic approaches against common structural features of toxic oligomers shared by multiple amyloidogenic proteins. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014, 88, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbimbo, B.P.; Ippati, S.; Watling, M. Should drug discovery scientists still embrace the amyloid hypothesis for Alzheimer’s disease or should they be looking elsewhere? Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreiser, R.P.; Wright, A.K.; Block, N.R.; Hollows, J.E.; Nguyen, L.T.; Leforte, K.; Mannini, B.; Vendruscolo, M.; Limbocker, R. Therapeutic strategies to reduce the toxicity of misfolded protein oligomers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.T.; Lourenco, M.V.; Oliveira, M.M.; De Felice, F.G. Soluble amyloid-β oligomers as synaptotoxins leading to cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Batista, A.F.; Rody, T.; Forny-Germano, L.; Cerdeiro, S.; Bellio, M.; Ferreira, S.T.; Munoz, D.P.; De Felice, F.G. Interleukin-1β mediates alterations in mitochondrial fusion/fission proteins and memory impairment induced by amyloid-β oligomers. J. Neuroinflammation 2021, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigin, V.L.; Nichols, E.; Alam, T.; Bannick, M.S.; Beghi, E.; Blake, N.; Culpepper, W.J.; Dorsey, E.R.; Elbaz, A.; Ellenbogen, R.G.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 459–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dickson, D.W. Neuropathology of Parkinson disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2018, 46, S30–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betarbet, R.; Sherer, T.B.; MacKenzie, G.; Garcia-Osuna, M.; Panov, A.V.; Greenamyre, J.T. Chronic systemic pesticide exposure reproduces features of Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2000, 3, 1301–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Myung, W.; Kim, D.K.; Kim, S.E.; Kim, C.T.; Kim, H. Short-term air pollution exposure aggravates Parkinson’s disease in a population-based cohort. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmed, H.; Abushouk, A.I.; Gabr, M.; Negida, A.; Abdel-Daim, M.M. Parkinson’s disease and pesticides: A meta-analysis of disease connection and genetic alterations. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 90, 638–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasdagli, M.I.; Katsouyanni, K.; Dimakopoulou, K.; Samoli, E. Air pollution and Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis up to 2018. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2019, 222, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surmeier, D.J. Determinants of dopaminergic neuron loss in Parkinson’s disease. FEBS J. 2018, 285, 3657–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Emamzadeh, F.N.; Surguchov, A. Parkinson’s disease: Biomarkers, treatment, and risk factors. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draoui, A.; El Hiba, O.; Aimrane, A.; El Khiat, A.; Gamrani, H. Parkinson’s disease: From bench to bedside. Rev. Neurol. 2020, 176, 543–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charvin, D.; Medori, R.; Hauser, R.A.; Rascol, O. Therapeutic strategies for Parkinson disease: Beyond dopaminergic drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 804–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahn, S. The 200-year journey of Parkinson disease: Reflecting on the past and looking towards the future. Park. Relat. Disord. 2018, 46, S1–S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams-Gray, C.H.; Worth, P.F. Parkinson’s disease. Medicine 2020, 48, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarthing, K.; Buff, S.; Rafaloff, G.; Dominey, T.; Wyse, R.K.; Stott, S.R.W. Parkinson’s Disease Drug Therapies in the Clinical Trial Pipeline: 2020. J. Parkinsons. Dis. 2020, 10, 757–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, W.R.; Lees, A.J. The relevance of the Lewy body to the pathogenesis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1988, 51, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Spillantini, M.G.; Schmidt, M.L.; Lee, V.M.Y.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Jakes, R.; Goedert, M. a -Synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature 1997, 388, 839–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spillantini, M.G.; Crowther, R.A.; Jakes, R.; Hasegawa, M.; Goedert, M. α-Synuclein in filamentous inclusions of Lewy bodies from Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 6469–6473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Meade, R.M.; Fairlie, D.P.; Mason, J.M. Alpha-synuclein structure and Parkinson’s disease - Lessons and emerging principles. Mol. Neurodegener. 2019, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mahul-Mellier, A.L.; Burtscher, J.; Maharjan, N.; Weerens, L.; Croisier, M.; Kuttler, F.; Leleu, M.; Knott, G.W.; Lashuel, H.A. The process of Lewy body formation, rather than simply α-synuclein fibrillization, is one of the major drivers of neurodegeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 4971–4982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Du, X.Y.; Xie, X.X.; Liu, R.T. The role of α-synuclein oligomers in parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boi, L.; Pisanu, A.; Palmas, M.F.; Fusco, G.; Carboni, E.; Casu, M.A.; Satta, V.; Scherma, M.; Janda, E.; Mocci, I.; et al. Modeling Parkinson’s disease neuropathology and symptoms by intranigral inoculation of preformed human α-synuclein oligomers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danon, J.J.; Reekie, T.A.; Kassiou, M. Challenges and Opportunities in Central Nervous System Drug Discovery. Trends Chem. 2019, 1, 612–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallucci, G.R.; Klenerman, D.; Rubinsztein, D.C. Developing Therapies for Neurodegenerative Disorders: Insights from Protein Aggregation and Cellular Stress Responses. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 36, 165–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imbimbo, B.P.; Ippati, S.; Watling, M.; Balducci, C.; Imbimbo, B.P.; Ippati, S.; Watling, M.; Balducci, C.; Imbimbo, B.P.; Ippati, S.; et al. Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery Accelerating Alzheimer ’ s disease drug discovery and development: What ’ s the way forward ? Accelerating Alzheimer ’ s disease drug discovery and development: What ’ s the way. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, C.X.; Liu, F.; Iqbal, K. Multifactorial Hypothesis and Multi-Targets for Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 64, S107–S117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheong, S.L.; Federico, S.; Spalluto, G.; Klotz, K.N.; Pastorin, G. The current status of pharmacotherapy for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease: Transition from single-target to multitarget therapy. Drug Discov. Today 2019, 24, 1769–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertini, C.; Salerno, A.; de Sena, P.; Pinheiro, M.; Bolognesi, M.L. From combinations to multitarget-directed ligands: A continuum in Alzheimer ’ s disease polypharmacology. Med. Res. Rev. 2020, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Jahan, S.; Imtiyaz, Z.; Alshahrani, S.; Makeen, H.A.; Alshehri, B.M.; Kumar, A.; Arafah, A.; Rehman, M.U. Neuroprotection: Targeting multiple pathways by naturally occurring phytochemicals. Biomedicines 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, B.; Lucariello, G.; Capasso, R. Topical Collection “Pharmacology of Medicinal Plants”. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solanki, I.; Parihar, P.; Parihar, M.S. Neurodegenerative diseases: From available treatments to prospective herbal therapy. Neurochem. Int. 2016, 95, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, M.; Nawaz, A. Effects of medicinal plants on Alzheimer’s disease and memory deficits. Neural Regen. Res. 2017, 12, 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastav, S.; Fatima, M.; Mondal, A.C. Important medicinal herbs in Parkinson’s disease pharmacotherapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 92, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, H.; Nagoor Meeran, M.F.; Azimullah, S.; Adem, A.; Sadek, B.; Ojha, S.K. Plant Extracts and Phytochemicals Targeting α-Synuclein Aggregation in Parkinson’s Disease Models. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 9, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rabiei, Z.; Solati, K.; Amini-Khoei, H. Phytotherapy in treatment of Parkinson’s disease: A review. Pharm. Biol. 2019, 57, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gregory, J.; Vengalasetti, Y.V.; Bredesen, D.E.; Rao, R.V. Neuroprotective herbs for the management of Alzheimer’s disease. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs over the Nearly Four Decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 770–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, M.; Lankatillake, C.; Dias, D.A.; Docea, A.O.; Mahomoodally, M.F.; Lobine, D.; Chazot, P.L.; Kurt, B.; Boyunegmez Tumer, T.; Catarina Moreira, A.; et al. Impact of Natural Compounds on Neurodegenerative Disorders: From Preclinical to Pharmacotherapeutics. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pohl, F.; Lin, P.K.T. The potential use of plant natural products and plant extracts with antioxidant properties for the prevention/treatment of neurodegenerative diseases: In vitro, in vivo and clinical trials. Molecules 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cardoso, S.M. Special issue: The antioxidant capacities of natural products. Molecules 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thapa, A.; Carroll, N.J. Dietary modulation of oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pogačnik, L.; Ota, A.; Poklar Ulrih, N. An Overview of Crucial Dietary Substances and Their Modes of Action for Prevention of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cells 2020, 9, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hano, C.; Tungmunnithum, D. Plant Polyphenols, More than Just Simple Natural Antioxidants: Oxidative Stress, Aging and Age-Related Diseases. Medicines 2020, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, C.; Fraga, C.A.M.; Sousa, M.E.; Tarozzi, A. Editorial: Oxidative Stress: How Has It Been Considered in the Design of New Drug Candidates for Neurodegenerative Diseases? Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhullar, K.S.; Rupasinghe, H.P.V. Polyphenols: Multipotent therapeutic agents in neurodegenerative diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Devi, S.; Kumar, V.; Singh, S.K.; Dubey, A.K.; Kim, J.J. Flavonoids: Potential candidates for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluso, I.; Serafini, M. Antioxidants from black and green tea: From dietary modulation of oxidative stress to pharmacological mechanisms. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 1195–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pervin, M.; Unno, K.; Ohishi, T.; Tanabe, H.; Miyoshi, N.; Nakamura, Y. Beneficial Effects of Green Tea Catechins on Neurodegenerative Diseases. Molecules 2018, 23, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guest, J.; Grant, R. The Benefits of Natural Products for Neurodegenerative Diseases; Advances in Neurobiology; Essa, M.M., Akbar, M., Guillemin, G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 12, ISBN 978-3-319-28381-4. [Google Scholar]

- Di Paolo, M.; Papi, L.; Gori, F.; Turillazzi, E. Natural products in neurodegenerative diseases: A great promise but an ethical challenge. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maher, P. The potential of flavonoids for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Uddin, M.S.; Kabir, M.T.; Niaz, K.; Jeandet, P.; Clément, C.; Mathew, B.; Rauf, A.; Rengasamy, K.R.R.; Sobarzo-Sánchez, E.; Ashraf, G.M.; et al. Molecular Insight into the Therapeutic Promise of Flavonoids against Alzheimer’s Disease. Molecules 2020, 25, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Atanasov, A.G.; Zotchev, S.B.; Dirsch, V.M.; Orhan, I.E.; Banach, M.; Rollinger, J.M.; Barreca, D.; Weckwerth, W.; Bauer, R.; Bayer, E.A.; et al. Natural products in drug discovery: Advances and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Sairazi, N.S.; Sirajudeen, K.N.S. Natural Products and Their Bioactive Compounds: Neuroprotective Potentials against Neurodegenerative Diseases. Evidence-based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhouafli, Z.; Cuanalo-Contreras, K.; Hayouni, E.A.; Mays, C.E.; Soto, C.; Moreno-Gonzalez, I. Inhibition of protein misfolding and aggregation by natural phenolic compounds. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 3521–3538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henríquez, G.; Gomez, A.; Guerrero, E.; Narayan, M. Potential Role of Natural Polyphenols against Protein Aggregation Toxicity: In Vitro, In Vivo, and Clinical Studies. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2020, 11, 2915–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukutomi, R.; Ohishi, T.; Koyama, Y.; Pervin, M.; Nakamura, Y.; Isemura, M. Beneficial Effects of Epigallocatechin-3-O-Gallate, Chlorogenic Acid, Resveratrol, and Curcumin on Neurodegenerative Diseases. Molecules 2021, 26, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Wang, X.P.; Yang, S.G.; Wang, Y.J.; Zhang, X.; Du, X.T.; Sun, X.X.; Zhao, M.; Huang, L.; Liu, R.T. Resveratrol inhibits beta-amyloid oligomeric cytotoxicity but does not prevent oligomer formation. Neurotoxicology 2009, 30, 986–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez Del Amo, J.M.; Fink, U.; Dasari, M.; Grelle, G.; Wanker, E.E.; Bieschke, J.; Reif, B. Structural properties of EGCG-induced, nontoxic Alzheimer’s disease Aβ oligomers. J. Mol. Biol. 2012, 421, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.K.; Kotia, V.; Ghosh, D.; Mohite, G.M.; Kumar, A.; Maji, S.K. Curcumin modulates α-synuclein aggregation and toxicity. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2013, 4, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thapa, A.; Jett, S.D.; Chi, E.Y. Curcumin Attenuates Amyloid-β Aggregate Toxicity and Modulates Amyloid-β Aggregation Pathway. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2016, 7, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.E.; Rhoo, K.Y.; Lee, S.; Lee, J.T.; Park, J.H.; Bhak, G.; Paik, S.R. EGCG-mediated Protection of the Membrane Disruption and Cytotoxicity Caused by the “Active Oligomer” of α-Synuclein. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Terry, C. Insights from nature: A review of natural compounds that target protein misfolding in vivo. Curr. Res. Biotechnol. 2020, 2, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bemporad, F.; Chiti, F. Protein misfolded oligomers: Experimental approaches, mechanism of formation, and structure-toxicity relationships. Chem. Biol. 2012, 19, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lim, K.H. Diverse misfolded conformational strains and cross-seeding of misfolded proteins implicated in neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2019, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jucker, M.; Walker, L.C. Propagation and spread of pathogenic protein assemblies in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 1341–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, C.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Lee, V.M.Y. Protein transmission in neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2020, 16, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdà-Costa, N.; Esteras-Chopo, A.; Avilés, F.X.; Serrano, L.; Villegas, V. Early Kinetics of Amyloid Fibril Formation Reveals Conformational Reorganisation of Initial Aggregates. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 366, 1351–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilie, I.M.; Caflisch, A. Simulation Studies of Amyloidogenic Polypeptides and Their Aggregates. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 6956–6993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusiner, S. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science 1982, 216, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Prusiner, S.B. Biology and Genetics of Prions Causing Neurodegeneration. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2013, 47, 601–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leighton, P.L.A.; Ted Allison, W. Protein misfolding in prion and prion-like diseases: Reconsidering a required role for protein loss-of-function. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2016, 54, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jaunmuktane, Z.; Brandner, S. Invited Review: The role of prion-like mechanisms in neurodegenerative diseases. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2020, 46, 522–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McAlary, L.; Plotkin, S.S.; Yerbury, J.J.; Cashman, N.R. Prion-Like Propagation of Protein Misfolding and Aggregation in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2019, 12, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duyckaerts, C.; Clavaguera, F.; Potier, M.C. The prion-like propagation hypothesis in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2019, 32, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.C.; Jucker, M. Neurodegenerative Diseases: Expanding the Prion Concept. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 38, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Oliveri, V. Toward the discovery and development of effective modulators of α-synuclein amyloid aggregation. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 167, 10–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagano, K.; Tomaselli, S.; Molinari, H.; Ragona, L. Natural Compounds as Inhibitors of Aβ Peptide Aggregation: Chemical Requirements and Molecular Mechanisms. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieschke, J.; Russ, J.; Friedrich, R.P.; Ehrnhoefer, D.E.; Wobst, H.; Neugebauer, K.; Wanker, E.E. EGCG remodels mature α-synuclein and amyloid-β fibrils and reduces cellular toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. US.A 2010, 107, 7710–7715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lorenzen, N.; Nielsen, S.B.; Yoshimura, Y.; Vad, B.S.; Andersen, C.B.; Betzer, C.; Kaspersen, J.D.; Christiansen, G.; Pedersen, J.S.; Jensen, P.H.; et al. How epigallocatechin gallate can inhibit α-synuclein oligomer toxicity in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 21299–21310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wobst, H.J.; Sharma, A.; Diamond, M.I.; Wanker, E.E.; Bieschke, J. The green tea polyphenol (-)-epigallocatechin gallate prevents the aggregation of tau protein into toxic oligomers at substoichiometric ratios. FEBS Lett. 2015, 589, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, J.; Liang, Q.; Sun, Q.; Chen, C.; Xu, L.; Ding, Y.; Zhou, P. The green tea polyphenol (-)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) inhibits fibrillation, disaggregates amyloid fibrils of α-synuclein, and protects PC12 cells against α-synuclein-induced toxicity. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 32508–32517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abelein, A.; Abrahams, J.P.; Danielsson, J.; Gräslund, A.; Jarvet, J.; Luo, J.; Tiiman, A.; Wärmländer, S.K.T.S. The hairpin conformation of the amyloid β peptide is an important structural motif along the aggregation pathway Topical Issue in honor of Ivano Bertini Guest editors: Lucia Banci, Claudio Luchinat. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 19, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, M.P.; Barlow, A.K.; Chromy, B.A.; Edwards, C.; Freed, R.; Liosatos, M.; Morgan, T.E.; Rozovsky, I.; Trommer, B.; Viola, K.L.; et al. Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Aβ1-42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 6448–6453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferreira, S.T.; Klein, W.L. The Aβ oligomer hypothesis for synapse failure and memory loss in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2011, 96, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Galzitskaya, O.V. Oligomers Are Promising Targets for Drug Development in the Treatment of Proteinopathies. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2020, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fantini, J.; Chahinian, H.; Yahi, N. Progress toward Alzheimer’s disease treatment: Leveraging the Achilles’ heel of Aβ oligomers? Protein Sci. 2020, 29, 1748–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longhena, F.; Faustini, G.; Spillantini, M.G.; Bellucci, A. Living in promiscuity: The multiple partners of alpha-synuclein at the synapse in physiology and pathology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bartels, T.; Choi, J.G.; Selkoe, D.J. α-Synuclein occurs physiologically as a helically folded tetramer that resists aggregation. Nature 2011, 477, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fauvet, B.; Mbefo, M.K.; Fares, M.B.; Desobry, C.; Michael, S.; Ardah, M.T.; Tsika, E.; Coune, P.; Prudent, M.; Lion, N.; et al. α-Synuclein in central nervous system and from erythrocytes, mammalian cells, and Escherichia coli exists predominantly as disordered monomer. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 15345–15364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Theillet, F.X.; Binolfi, A.; Bekei, B.; Martorana, A.; Rose, H.M.; Stuiver, M.; Verzini, S.; Lorenz, D.; Van Rossum, M.; Goldfarb, D.; et al. Structural disorder of monomeric α-synuclein persists in mammalian cells. Nature 2016, 530, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goedert, M.; Jakes, R.; Spillantini, M.G. The Synucleinopathies: Twenty Years on. J. Parkinsons. Dis. 2017, 7, S53–S71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brás, I.C.; Dominguez-Meijide, A.; Gerhardt, E.; Koss, D.; Lázaro, D.F.; Santos, P.I.; Vasili, E.; Xylaki, M.; Outeiro, T.F. Synucleinopathies: Where we are and where we need to go. J. Neurochem. 2020, 153, 433–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Outeiro, T.F. Emerging concepts in synucleinopathies. Acta Neuropathol. 2021, 36, 229–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teil, M.; Arotcarena, M.L.; Faggiani, E.; Laferriere, F.; Bezard, E.; Dehay, B. Targeting α-synuclein for PD Therapeutics: A Pursuit on All Fronts. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ghiglieri, V.; Calabrese, V.; Calabresi, P. Alpha-synuclein: From early synaptic dysfunction to neurodegeneration. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lashuel, H.A.; Overk, C.R.; Oueslati, A.; Masliah, E. The many faces of α-synuclein: From structure and toxicity to therapeutic target. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Villar-Piqué, A.; Lopes da Fonseca, T.; Outeiro, T.F. Structure, function and toxicity of alpha-synuclein: The Bermuda triangle in synucleinopathies. J. Neurochem. 2016, 139, 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winner, B.; Jappelli, R.; Maji, S.K.; Desplats, P.A.; Boyer, L.; Aigner, S.; Hetzer, C.; Loher, T.; Vilar, M.; Campioni, S.; et al. In vivo demonstration that α-synuclein oligomers are toxic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 4194–4199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lashuel, H.A.; Petre, B.M.; Wall, J.; Simon, M.; Nowak, R.J.; Walz, T.; Lansbury, P.T. A-Synuclein, Especially the Parkinson’S Disease-Associated Mutants, Forms Pore-Like Annular and Tubular Protofibrils. J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 322, 1089–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lashuel, H.A.; Hartley, D.; Petre, B.M.; Walz, T.; Lansbury, P.T. Neurodegenerative disease: Amyloid pores from pathogenic mutations. Nature 2002, 418, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsigelny, I.F.; Sharikov, Y.; Wrasidlo, W.; Gonzalez, T.; Desplats, P.A.; Crews, L.; Spencer, B.; Masliah, E. Role of α-synuclein penetration into the membrane in the mechanisms of oligomer pore formation. FEBS J. 2012, 279, 1000–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choi, Y.T.; Jung, C.H.; Lee, S.R.; Bae, J.H.; Baek, W.K.; Suh, M.H.; Park, J.; Park, C.W.; Suh, S. Il The green tea polyphenol (-)-epigallocatechin gallate attenuates β-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity in cultured hippocampal neurons. Life Sci. 2001, 70, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, R.R.; Chen, J.Z.; Chen, H.; Kang, X.G.; Li, M.G.; Wang, B.R. Neuroprotective effects of (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) on paraquat-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells. Cell Biol. Int. 2008, 32, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimmyo, Y.; Kihara, T.; Akaike, A.; Niidome, T.; Sugimoto, H. Epigallocatechin-3 -gallate and curcumin suppress amyloid beta-induced beta-site APP cleaving enzyme-1 upregulation. Neuroreport 2008, 19, 1329–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xu, S.; Xu, X.; Chan, P. (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate protects SH-SY5Y cells against 6-OHDA-induced cell death through stat3 activation. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2009, 17, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.Y.; Lee, C.; Park, G.H.; Jang, J.H. Neuroprotective effect of epigallocatechin-3-gallate against β-amyloid-induced oxidative and nitrosative cell death via augmentation of antioxidant defense capacity. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2009, 32, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.L.; Chen, T.F.; Chiu, M.J.; Way, T.D.; Lin, J.K. Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) suppresses β-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity through inhibiting c-Abl/FE65 nuclear translocation and GSK3β activation. Neurobiol. Aging 2009, 30, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldzio, R.; Radad, K.; Krewenka, C.; Kranner, B.; Duvigneau, J.C.; Wang, Y.; Rausch, W.D. Effects of epigallocatechin gallate on rotenone-injured murine brain cultures. J. Neural Transm. 2010, 117, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, K.K.; Truong, D.D. (-)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), a green tea polyphenol, reduces dichlorodiphenyl-trichloroethane (DDT)-induced cell death in dopaminergic SHSY-5Y cells. Neurosci. Lett. 2010, 482, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Q.; Ye, L.; Xu, X.; Huang, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, X. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate suppresses 1-methyl-4-phenyl-pyridine-induced oxidative stress in PC12 cells via the SIRT1/PGC-1α signaling pathway. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, D.; Kanthasamy, A.G.; Reddy, M.B. EGCG Protects against 6-OHDA-Induced Neurotoxicity in a Cell Culture Model. Parkinsons. Dis. 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheng-Chung Wei, J.; Huang, H.C.; Chen, W.J.; Huang, C.N.; Peng, C.H.; Lin, C.L. Epigallocatechin gallate attenuates amyloid β-induced inflammation and neurotoxicity in EOC 13.31 microglia. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 770, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Zhao, J.; Ding, L.; Ding, Y.; Zhou, P. Complex of EGCG with Cu(II) suppresses amyloid aggregation and Cu(II)-induced cytotoxicity of α-synuclein. Molecules 2019, 24, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rezai-Zadeh, K.; Shytle, D.; Sun, N.; Mori, T.; Hou, H.; Jeanniton, D.; Ehrhart, J.; Townsend, K.; Zeng, J.; Morgan, D.; et al. Green tea epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) modulates amyloid precursor protein cleavage and reduces cerebral amyloidosis in Alzheimer transgenic mice. J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 8807–8814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rasoolijazi, H.; Joghataie, M.T.; Roghani, M.; Nobakht, M. The beneficial effect of (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate in an experimental model of Alzheimer’s disease in rat: A behavioral analysis. Iran. Biomed. J. 2007, 11, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rezai-Zadeh, K.; Arendash, G.W.; Hou, H.; Fernandez, F.; Jensen, M.; Runfeldt, M.; Shytle, R.D.; Tan, J. Green tea epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) reduces β-amyloid mediated cognitive impairment and modulates tau pathology in Alzheimer transgenic mice. Brain Res. 2008, 1214, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.K.; Yuk, D.Y.; Lee, J.W.; Lee, S.Y.; Ha, T.Y.; Oh, K.W.; Yun, Y.P.; Hong, J.T. (-)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate prevents lipopolysaccharide-induced elevation of beta-amyloid generation and memory deficiency. Brain Res. 2009, 1250, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.W.; Lee, Y.K.; Ban, J.O.; Ha, T.Y.; Yun, Y.P.; Han, S.B.; Oh, K.W.; Hong, J.T. Green tea (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits β-amyloid-induced cognitive dysfunction through modification of secretase activity via inhibition of ERK and NF-κB pathways in mice. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1987–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Zhao, L.; Wei, M.J.; Yao, W.F.; Zhao, H.S.; Chen, F.J. Neuroprotective effects of (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate on aging mice induced by D-galactose. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2009, 32, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, Y.J.; Choi, D.Y.; Yun, Y.P.; Han, S.B.; Oh, K.W.; Hong, J.T. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate prevents systemic inflammation-induced memory deficiency and amyloidogenesis via its anti-neuroinflammatory properties. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2013, 24, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasibetti, R.; Tramontina, A.C.; Costa, A.P.; Dutra, M.F.; Quincozes-Santos, A.; Nardin, P.; Bernardi, C.L.; Wartchow, K.M.; Lunardi, P.S.; Gonçalves, C.A. Green tea (-)epigallocatechin-3-gallate reverses oxidative stress and reduces acetylcholinesterase activity in a streptozotocin-induced model of dementia. Behav. Brain Res. 2013, 236, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.M.; Klakotskaia, D.; Ajit, D.; Weisman, G.A.; Wood, W.G.; Sun, G.Y.; Serfozo, P.; Simonyi, A.; Schachtman, T.R. Beneficial effects of dietary EGCG and voluntary exercise on behavior in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2015, 44, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Rong, C.; Chen, Y.; Yang, C.; Hu, Q.; Mo, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gu, X.; Zhang, L.; He, W.; et al. (-)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate attenuates cognitive deterioration in Alzheimer’s disease model mice by upregulating neprilysin expression. Exp. Cell Res. 2015, 334, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Nan, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, S. (-)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate ameliorates memory impairment and rescues the abnormal synaptic protein levels in the frontal cortex and hippocampus in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroreport 2017, 28, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.A.; Bhardwaj, V.; Ravi, C.; Ramesh, N.; Mandal, A.K.A.; Khan, Z.A. EGCG nanoparticles attenuate aluminum chloride induced neurobehavioral deficits, beta amyloid and tau pathology in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, K.; Liu, M.; Zhong, X.; Yao, W.; Xiao, Q.; Wen, Q.; Yang, B.; Wei, M. Epigallocatechin Gallate Reduces Amyloid β-Induced Neurotoxicity via Inhibiting Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Mediated Apoptosis. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, T.; Koyama, N.; Tan, J.; Segawa, T.; Maeda, M.; Town, T. Combined treatment with the phenolics ()-epigallocatechin-3-gallate and ferulic acid improves cognition and reduces Alzheimer-like pathology in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 2714–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cano, A.; Ettcheto, M.; Chang, J.H.; Barroso, E.; Espina, M.; Kühne, B.A.; Barenys, M.; Auladell, C.; Folch, J.; Souto, E.B.; et al. Dual-drug loaded nanoparticles of Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG)/Ascorbic acid enhance therapeutic efficacy of EGCG in a APPswe/PS1dE9 Alzheimer’s disease mice model. J. Control. Release 2019, 301, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ettcheto, M.; Cano, A.; Manzine, P.R.; Busquets, O.; Verdaguer, E.; Castro-Torres, R.D.; García, M.L.; Beas-Zarate, C.; Olloquequi, J.; Auladell, C.; et al. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG) Improves Cognitive Deficits Aggravated by an Obesogenic Diet Through Modulation of Unfolded Protein Response in APPswe/PS1dE9 Mice. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 57, 1814–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Inhibition of Aβ aggregates in Alzheimer’s disease by epigallocatechin and epicatechin-3-gallate from green tea. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 105, 104382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levites, Y.; Weinreb, O.; Maor, G.; Youdim, M.B.H.; Mandel, S. Green tea polyphenol (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate prevents N-methyl-4-phenyl- 1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced dopaminergic neurodegeneration. J. Neurochem. 2001, 78, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.Y.; Park, C.S.; Kim, D.J.; Cho, M.H.; Jin, B.K.; Pie, J.E.; Chung, W.G. Prevention of nitric oxide-mediated 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced Parkinson’s disease in mice by tea phenolic epigallocatechin 3-gallate. Neurotoxicology 2002, 23, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitu Pinto, N.; Da Silva Alexandre, B.; Neves, K.R.T.; Silva, A.H.; Leal, L.K.A.M.; Viana, G.S.B. Neuroprotective Properties of the Standardized Extract from Camellia sinensis (Green Tea) and Its Main Bioactive Components, Epicatechin and Epigallocatechin Gallate, in the 6-OHDA Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Evidence-based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, Q.; Langley, M.; Kanthasamy, A.G.; Reddy, M.B. Epigallocatechin Gallate Has a Neurorescue Effect in a Mouse Model of Parkinson Disease. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 1926–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhou, T.; Zhu, M.; Liang, Z. (-)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate modulates peripheral immunity in the MPTP-induced mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 4883–4888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xu, Y.; Xie, M.; Xue, J.; Xiang, L.; Li, Y.; Xiao, J.; Xiao, G.; Wang, H.L. EGCG ameliorates neuronal and behavioral defects by remodeling gut microbiota and TotM expression in Drosophila models of Parkinson’s disease. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 5931–5950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tseng, H.C.; Wang, M.H.; Chang, K.C.; Soung, H.S.; Fang, C.H.; Lin, Y.W.; Li, K.Y.; Yang, C.C.; Tsai, C.C. Protective Effect of (−)Epigallocatechin-3-gallate on Rotenone-Induced Parkinsonism-like Symptoms in Rats. Neurotox. Res. 2020, 37, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Chen, S.; Li, X.; Luo, G.; Li, L.; Le, W. Neuroprotective effects of (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate in a transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurochem. Res. 2006, 31, 1263–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, S.H.; Lee, S.M.; Kim, H.Y.; Lee, K.Y.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, H.T.; Kim, J.; Kim, M.H.; Hwang, M.S.; Song, C.; et al. The effect of epigallocatechin gallate on suppressing disease progression of ALS model mice. Neurosci. Lett. 2006, 395, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Kumar, A. Effect of lycopene and epigallocatechin-3-gallate against 3-nitropropionic acid induced cognitive dysfunction and glutathione depletion in rat: A novel nitric oxide mechanism. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009, 47, 2522–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, N.; Saraiva, M.J.; Almeida, M.R. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate as a potential therapeutic drug for TTR-related amyloidosis: “In vivo” evidence from FAP mice models. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruana, M.; Högen, T.; Levin, J.; Hillmer, A.; Giese, A.; Vassallo, N. Inhibition and disaggregation of α-synuclein oligomers by natural polyphenolic compounds. FEBS Lett. 2011, 585, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Palhano, F.L.; Lee, J.; Grimster, N.P.; Kelly, J.W. Toward the molecular mechanism(s) by which EGCG treatment remodels mature amyloid fibrils. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 7503–7510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sironi, E.; Colombo, L.; Lompo, A.; Messa, M.; Bonanomi, M.; Regonesi, M.E.; Salmona, M.; Airoldi, C. Natural compounds against neurodegenerative diseases: Molecular characterization of the interaction of catechins from green tea with Aβ1-42, PrP106-126, and ataxin-3 oligomers. Chem. A Eur. J. 2014, 20, 13793–13800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, N.N.; Kumar, R.; Panigrahi, R.; Navalkar, A.; Ghosh, D.; Sahay, S.; Mondal, M.; Kumar, A.; Maji, S.K. Comparison of α-Synuclein Fibril Inhibition by Four Different Amyloid Inhibitors. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2017, 8, 2722–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, R.; Vanschouwen, B.; Jafari, N.; Ni, X.; Ortega, J.; Melacini, G. Molecular mechanism for the (-)-Epigallocatechin gallate-induced toxic to nontoxic remodeling of Aβ oligomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 13720–13734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, R.; Akcan, M.; Khondker, A.; Rheinstädter, M.C.; Bozelli, J.C.; Epand, R.M.; Huynh, V.; Wylie, R.G.; Boulton, S.; Huang, J.; et al. Atomic resolution map of the soluble amyloid beta assembly toxic surfaces. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 6072–6082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, G.; Xue, C.; Wang, H.; Guo, Z. Distinguishing the Effect on the Rate and Yield of Aβ42 Aggregation by Green Tea Polyphenol EGCG. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 21497–21505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, L.; Messias, B.; Pereira-Neves, A.; Azevedo, E.P.; Araújo, J.; Foguel, D.; Palhano, F.L. Green Tea Polyphenol Microparticles Based on the Oxidative Coupling of EGCG Inhibit Amyloid Aggregation/Cytotoxicity and Serve as a Platform for Drug Delivery. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 4414–4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butterfield, D.A. β-amyloid-associated free radical oxidative stress and neurotoxicity: Implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1997, 10, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatin, S.M.; Varadarajan, S.; Link, C.D.; Butterfield, D.A. In vitro and in vivo oxidative stress associated with Alzheimer’s amyloid β-peptide (1-42). Neurobiol. Aging 1999, 20, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadarajan, S.; Yatin, S.; Aksenova, M.; Butterfield, D.A. Review: Alzheimer’s amyloid β-peptide-associated free radical oxidative stress and neurotoxicity. J. Struct. Biol. 2000, 130, 184–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamagno, E.; Bardini, P.; Obbili, A.; Vitali, A.; Borghi, R.; Zaccheo, D.; Pronzato, M.A.; Danni, O.; Smith, M.A.; Perry, G.; et al. Oxidative stress increases expression and activity of BACE in NT2 neurons. Neurobiol. Dis. 2002, 10, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maia, M.A.; Sousa, E. BACE-1 and γ-secretase as therapeutic targets for Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cheng, X.R.; Zhou, W.X.; Zhang, Y.X. The behavioral, pathological and therapeutic features of the senescence-accelerated mouse prone 8 strain as an Alzheimer’s disease animal model. Ageing Res. Rev. 2014, 13, 13–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blesa, J.; Przedborski, S. Parkinson’s disease: Animal models and dopaminergic cell vulnerability. Front. Neuroanat. 2014, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sampson, T.R.; Debelius, J.W.; Thron, T.; Janssen, S.; Shastri, G.G.; Ilhan, Z.E.; Challis, C.; Schretter, C.E.; Rocha, S.; Gradinaru, V.; et al. Gut Microbiota Regulate Motor Deficits and Neuroinflammation in a Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Cell 2016, 167, 1469–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Most, J.; Penders, J.; Lucchesi, M.; Goossens, G.H.; Blaak, E.E. Gut microbiota composition in relation to the metabolic response to 12-week combined polyphenol supplementation in overweight men and women. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 71, 1040–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; De Bruijn, W.J.C.; Bruins, M.E.; Vincken, J.P. Reciprocal Interactions between Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) and Human Gut Microbiota in Vitro. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 9804–9815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, F.; Li, C.; Chu, F.; Tian, X.; Zhu, J. Target Dysbiosis of Gut Microbes as a Future Therapeutic Manipulation in Alzheimer ’ s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2020; 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, D.; Ali, S.A.; Singh, R.K. Emerging role of gut microbiota in modulation of neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration with emphasis on Alzheimer’s disease. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 106, 110112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, J.; Maaß, S.; Schuberth, M.; Giese, A.; Oertel, W.H.; Poewe, W.; Trenkwalder, C.; Wenning, G.K.; Mansmann, U.; Südmeyer, M.; et al. Safety and efficacy of epigallocatechin gallate in multiple system atrophy (PROMESA): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 724–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.; Pinto, M.; Fernandes, C.; Benfeito, S.; Borges, F. Antioxidant Therapy and Neurodegenerative Disorders: Lessons From Clinical Trials; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; ISBN 9780128012383. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Z.Y.; Li, X.M.; Liang, J.P.; Xiang, L.P.; Wang, K.R.; Shi, Y.L.; Yang, R.; Shi, M.; Ye, J.H.; Lu, J.L.; et al. Bioavailability of tea catechins and its improvement. Molecules 2018, 23, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sang, S.; Lee, M.J.; Hou, Z.; Ho, C.T.; Yang, C.S. Stability of tea polyphenol (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate and formation of dimers and epimers under common experimental conditions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 9478–9484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, C.; Chen, J.; Li, X. Biocompatible, functional spheres based on oxidative coupling assembly of green tea polyphenols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 4179–4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, Y.; Brender, J.R.; Hartman, K.; Ramamoorthy, A.; Marsh, E.N.G. Alternative pathways of human islet amyloid polypeptide aggregation distinguished by 19F nuclear magnetic resonance-detected kinetics of monomer consumption. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 8154–8162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nie, R.Z.; Zhu, W.; Peng, J.M.; Ge, Z.; Li, C. mei Comparison of disaggregative effect of A-type EGCG dimer and EGCG monomer on the preformed bovine insulin amyloid fibrils. Biophys. Chem. 2017, 230, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, D.; Bhattacharyya, D.; Bhunia, A. Do catechins (ECG and EGCG)bind to the same site as thioflavin T (ThT) in amyloid fibril? Answer from saturation transfer difference NMR. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kelley, M.; Sant’Anna, R.; Fernandes, L.; Palhano, F.L. Pentameric Thiophene as a Probe to Monitor EGCG’s Remodeling Activity of Mature Amyloid Fibrils: Overcoming Signal Artifacts of Thioflavin T. ACS Omega 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sternke-Hoffmann, R.; Peduzzo, A.; Bolakhrif, N.; Haas, R.; Buell, A.K. The aggregation conditions define whether EGCG is an inhibitor or enhancer of α-synuclein amyloid fibril formation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bolognesi, B.; Kumita, J.R.; Barros, T.P.; Esbjorner, E.K.; Luheshi, L.M.; Crowther, D.C.; Wilson, M.R.; Dobson, C.M.; Favrin, G.; Yerbury, J.J. ANS binding reveals common features of cytotoxic amyloid species. ACS Chem. Biol. 2010, 5, 735–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiti, F.; Dobson, C.M. Protein misfolding, amyloid formation, and human disease: A summary of progress over the last decade. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 27–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladiwala, A.R.A.; Litt, J.; Kane, R.S.; Aucoin, D.S.; Smith, S.O.; Ranjan, S.; Davis, J.; Van Nostrand, W.E.; Tessier, P.M. Conformational differences between two amyloid βoligomers of similar size and dissimilar toxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 24765–24773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kotler, S.A.; Walsh, P.; Brender, J.R.; Ramamoorthy, A. Differences between amyloid-β aggregation in solution and on the membrane: Insights into elucidation of the mechanistic details of Alzheimer’s disease. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 6692–6700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Terry, C.; Harniman, R.L.; Sells, J.; Wenborn, A.; Joiner, S.; Saibil, H.R.; Miles, M.J.; Collinge, J.; Wadsworth, J.D.F. Structural features distinguishing infectious ex vivo mammalian prions from non-infectious fibrillar assemblies generated in vitro. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kollmer, M.; Close, W.; Funk, L.; Rasmussen, J.; Bsoul, A.; Schierhorn, A.; Schmidt, M.; Sigurdson, C.J.; Jucker, M.; Fändrich, M. Cryo-EM structure and polymorphism of Aβ amyloid fibrils purified from Alzheimer’s brain tissue. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Disease | Misfolded Protein(s) | Cell Types Primarily Affected | Clinical Feature(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s disease (AD) | Aβ, tau | Hippocampal neurons | Dementia |

| Parkinson’s disease (PD) | α-syn | Substantia nigra Dopaminergic neuron | Parkinsonism |

| Multiple system atrophy (MSA) | α-syn | Basal ganglia and/or cerebellar oligodendrocytes | Parkinsonism and/or ataxia |

| Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) | α-syn | Cortical and/or hippocampal and/or striatal neurons | Dementia and/or parkinsonism |

| Huntington disease (HD) | huntingtin | Striatal neurons | Dementia |

| Spinocerebellar ataxia | Ataxin | Cerebellar neurons | Cerebellar ataxia |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) | Ataxin, FUS, TDP43, C9orf72 or superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) | Motor neurons | Muscular atrophy |

| Frontotemporal dementia | FUS, TDP43, C9orf72 or SOD1 | Cortical neurons | Dementia |

| Gerstmann–Sträussler– Scheinker syndrome (GSS) | Prion protein | Cerebellar neurons | Ataxia |

| Fatal familial insomnia | Prion protein | Thalamic neurons | Insomnia |

| Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) | Prion protein | Cortical neurons | Dementia |

| Experimental Models | Cell Line | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Aβ-induced neurotoxicity model | Primary culture | Elevates cell survival and decreases the levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) and caspase activity [172] |

| Paraquat-induced PD model | PC12 cells | Protects against paraquat-induced apoptosis via modulating mitochondrial function [173] |

| Aβ1-42-exposure neuronal cells | Primary culture | Suppresses Aβ-induced BACE-1 upregulation [174] |

| 6-OHDA-induced PD model | SH-SY5Y cells | Protects against cell death through STAT3 activation [175] |

| Aβ-induced oxidative and nitrosative cell death | BV2 microglia | Fortifies cellular antioxidant glutathione pool via elevated expression of γ-glutamylcysteine ligase [176] |

| Human neuronal cells | MC65 cells (overexpressing APP) | Suppresses Aβ -induced neurotoxicity by inhibiting c-Abl/FE65 nuclear translocation and GSK3β activation [177] |

| ROT-injured murine brain cultures | Primary mesencephalic cell cultures | No influence on the survival of dopaminergic neurons in mesencephalic cultures [178] |

| DDT-induced cell death | SH-SY5Y cells | Activates endogenous neuroprotective mechanism(s) that can protect against cell death [179] |

| Fibril-induced neurotoxicity | HEK-293 cells(overexpressing α-syn)7PA2 cells(overexpressing APP)PC12 cells | Remodels mature α-syn and amyloid-β fibrils and reduces cellular toxicity [148] |

| MPP+-induced PD model | PC12 cells | Suppresses oxidative stress via the SIRT1/PGC-1α signaling pathway [180] |

| 6-OHDA-induced PD model | N27 cells | Pretreatment with EGCG protected against neurotoxicity by regulating genes and proteins involved in brain iron homeostasis, especially modulating hepcidin levels [181] |

| Microglia-mediated neuroinflammation | EOC 13.31 | Attenuates Aβ-induced inflammation and neurotoxicity [182] |

| α-syn induced neurotoxicity | α-syn transduced-PC12 cells | Protects cells against α-syn-induced damage by inhibiting the overexpression and fibrillation of α-syn in the cells [151] |

| Cu(II)-mediated toxicity | α-syn transduced-PC12 cells | Inhibits the overexpression and fibrillation of α-syn and reduces Cu(II)-induced oxidative stress [183] |

| Alzheimer’s Disease | ||

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Models | Animal Strain | Outcomes |

| Transgenic mice overproducing Aβ | Tg APPsw (line 2576) | Decreases Aβ levels and plaque associated with promotion of the nonamyloidogenic α-secretase proteolytic pathway [184] |

| Stereotaxic surgery lesion | Wistar rats | Restores β-amyloid-induced behavioral derangements relating to coordination and memory abilities [185] |

| Transgenic mice overproducing Aβ | Tg APPsw (line 2576) | Provides cognitive benefit and modulates tau pathology [186] |

| Transgenic mice overproducing Aβ | Tg APPsw (line 2576) | Inhibits GSK3β activation and c-Abl/Fe65 complex nuclear translocation [177]. |

| LPS-induced AD model | ICR mice | Inhibition of Aβ generation through the inhibition of β- and γ-secretase activity [187] |

| Aβ-induced AD model | ICR mice | Downregulates β- and γ-secretase activities and eventually decreases toxic Aβ levels in the cortex and hippocampus [188] |

| D-gal-induced AD model | Kunming mice | Increases the activities of antioxidant enzymes and reduces the activation of caspase-3 [189] |

| LPS-induced AD model | ICR mice | Prevents activation of astrocytes and elevation of proinflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, as well as the increase of inflammatory proteins such as inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) andcyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) [190] |

| Streptozotocin-induced AD model | Wistar rats | Neuroprotective effects through reversion of oxidative stress and decreased acetylcholinesterase activity [191] |

| Transgenic mice overproducing Aβ | Tg CRND8 mice | Ameliorates some behavioral manifestations and cognitive impairments [192] |

| Senescence-accelerated mouse (SAM) | SAMP8 | Attenuates cognitive deterioration by upregulating neprilysin expression [193] |

| Senescence-accelerated mouse (SAM) | SAMP8 | Oral consumption of EGCG ameliorates memory impairment and reduces the levels of Aβ1–42 and BACE-1 [194] |

| Aluminum-induced AD model | Wistar rats | Oral administration of EGCG nanoparticles attenuates neurobehavioral deficits and Aβ and Tau pathology [195] |

| Transgenic mice expressing mutant human APP and presenilin 1 | APP/PS1 mice | Inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum stress-associated neuronal apoptosis [196] |

| Transgenic mice expressing mutant human APP and presenilin 1 | APP/PS1 mice | Combination of EGCG with ferulic acid improves behavioral deficits, ameliorating cerebral amyloidosis and reducing Aβ generation [197] |

| Transgenic mice producing abundant Aβ plaques | APPswe/PS1dE9 mice | Oral administration of EGCG/ascorbic acid nanoparticles reduces Aβ plaque burden, Aβ42 peptide levels, and neuroinflammation while enhancing synaptogenesis, memory, and the learning process [198] |

| Transgenic mice producing abundant Aβ plaques fed with a high-fat diet (mixed model of familial AD and T2DM) | APPswe/PS1dE9 mice | Decreases brain Aβ production and plaque burden by increasing the levels of α-secretase and reduces neuroinflammation by the decrease in astrocyte reactivity and toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) levels [199] |

| Transgenic mice expressing mutant human APP and presenilin 1 | APP/PS1 mice | Reduces Aβ plaques in the brain [200] |

| Parkinson’s disease | ||

| Experimental models | Animal strain | Outcomes |

| MPTP-induced PD model | C57/BL mice | Alleviates dopamine neuron loss in the substantia nigra and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) protein level depletion [201] |

| MPTP-induced PD model | C57B6 mice | Decreases expressions of nitric oxide synthase in the substantia nigra [202] |

| 6-OHDA-induced PD model | Wistar rats | Reverses the striatal oxidative stress and immunohistochemistry alterations [203] |

| MPTP-induced PD model | C57BL/6J mice | Regulates the iron-export protein ferroportin in substantia nigra, reduces oxidative stress, and exerts a neurorescue effect [204] |

| MPTP-induced PD model | C57BL/6J mice | May exert neuroprotective effects by modulating peripheral immune response [205] |

| ROT-induced PD model | Drosophila melanogaster | Ameliorates neuronal and behavioral defects by remodeling gut microbiota and turandot M (TotM) expression [206] |

| ROT-induced PD model | Wistar rats | Reduces NO level and lipid peroxidation production, increases the levels of catecholamines in the striatum, and reduces the levels of neuroinflammatory and apoptotic markers [207] |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | ||

| Experimental models | Animal strain | Outcomes |

| Transgenic mice carrying a human SOD1 with a G93A mutation | B6SJL Tg (SOD1-G93A) | Increases the number of motor neurons and reduces the concentration of NF-kB caspase-3 and iNOS [208] |

| Transgenic mice carrying a human SOD1 with a G93A mutation | B6SJL Tg (SOD1-G93A) | Prolongs symptom onset and life span, preserving more survival signals and attenuating death signals [209] |

| Huntington’s disease | ||

| Experimental models | Animal strain | Outcomes |

| Transgenic flies expressing mutant huntingtin fragments with 93 glutamines | Drosophila melanogaster | Modulates early events in huntingtin misfolding and reduces toxicity [25] |

| 3-nitropropionic acid induced cognitive dysfunction and glutathione depletion | Wistar rats | Improves memory and restores glutathione system functioning [210] |

| Familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy (FAP) | ||

| Experimental models | Animal strain | Outcomes |

| Transgenic mice for human TTR | Tg hTTR V30M mice | Decreases non-fibrillar TTR deposition and disaggregation of amyloid deposits [211] |

| Protein | Main Outcome | Experimental Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Huntingtin | Modulates misfolding and oligomerization [25] | Dot-blot and AFM |

| Aβ42 α-syn | Redirects aggregation cascades and thus prevents the formation of toxic, β-sheet–rich aggregation products [26] | ThT fluorescence, TEM, CD, and dot-blot |

| Aβ42 α-syn | Binds to β-sheet-rich aggregates remodeling mature fibrils [148] | ThT fluorescence, TEM, AFM, and CD |

| α-syn | Inhibits and disaggregates oligomers [212] | Confocal single-particle fluorescence spectroscopy |

| Aβ40 | Induces the formation of nontoxic well-structured oligomers [128] | Solid-state NMR and MTT assay |

| Aβ40 | The amyloid remodeling activity is dependent on auto-oxidation of the EGCG [213] | ThT fluorescence, congo red assay, EM, AFM, CD, and MTT assay |

| Aβ42 PrP106–126 | Reduces the number of fibrils [214] | NMR, TEM, and CD |

| α-syn | Inhibits oligomer toxicity, moderately reduces membrane binding, and immobilizing the oligomer -terminal tail [149] | Calcein release assay, LSCM, NMR, TEM, CD, DLS, SAXS, MTT assay, and ITC |

| Tau | Prevents aggregation and toxicity [150] | ThT fluorescence, AFM, and MTT assay |

| α-syn | Inhibits fibrillation and disaggregates amyloid fibrils [174] | ThT fluorescence, CD, NMR, AFM, and TEM |

| α-syn | Aggregates showed small fibrillar length, and less toxicity correlates with reduction of exposed hydrophobic surface [215] | ThT fluorescence, CD, FTIR, ANS fluorescence, TEM, NMR, SPR, and MTT assay |

| α-syn | Protects against membrane disruption and cytotoxicity caused by oligomers [131] | ThT fluorescence, tyrosine intrinsic fluorescence, TEM, CD, DLS, FTIR, AFM, and MTT assay |

| Aβ40 | Remodels toxic oligomers to nontoxic aggregates [216] | DEST, NMR, ANS fluorescence, DLS, and TEM |

| Aβ42 | Remodels soluble Aβ assemblies into less toxic species with less exposed hydrophobic sites [217] | Comparative analysis of N-R2 and DEST NMR combined with WAXD, TEM, DLS, and extrinsic fluorescence |

| Aβ42 | Higher EGCG-to-Aβ42 ratios promote the rate of aggregation, while lower EGCG-to-Aβ42 ratios inhibit the aggregation rate [218] | ThT fluorescence, TEM and EPR |

| Aβ40 | Alleviates aggregation induced by metal ions [200] | ThT fluorescence, TEM, ICP-MS, UV–Vis spectroscopy |

| Tau | Dual effect on aggregation inhibition and disassembly of full-length Tau [28] | ThT fluorescence, MALDI-TOF analysis, and ITC |

| α-syn | EGCG microparticles reduce the cytotoxic effects of oligomers; besides, they increase the activity of other antiamyloidogenic compounds when used together [219] | ThT fluorescence, CD, DLS, TEM, and cell viability assay |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gonçalves, P.B.; Sodero, A.C.R.; Cordeiro, Y. Green Tea Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) Targeting Protein Misfolding in Drug Discovery for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 767. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/biom11050767

Gonçalves PB, Sodero ACR, Cordeiro Y. Green Tea Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) Targeting Protein Misfolding in Drug Discovery for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biomolecules. 2021; 11(5):767. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/biom11050767

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonçalves, Priscila Baltazar, Ana Carolina Rennó Sodero, and Yraima Cordeiro. 2021. "Green Tea Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) Targeting Protein Misfolding in Drug Discovery for Neurodegenerative Diseases" Biomolecules 11, no. 5: 767. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/biom11050767