Immune Priming Triggers Cell Wall Remodeling and Increased Resistance to Halo Blight Disease in Common Bean

Abstract

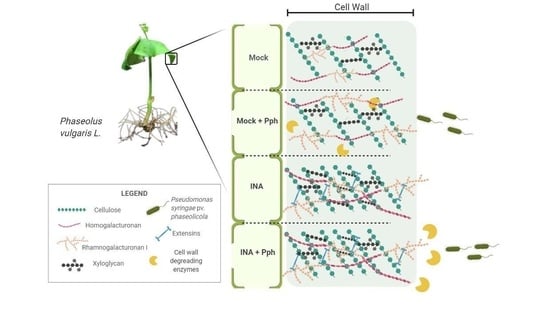

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. INA Reduced Bean Susceptibility to Pph and Increased Flg22-Triggered Response

2.2. Pph Inoculation and INA Priming Produce Different CW Fingerprinting Than That Observed in the Mock

2.3. INA Priming Induced Quantitative Changes in CW Polysaccharides Not Observed after the Pph Inoculation

2.4. INA Priming Increased the Average Molecular Weight of Polysaccharides in All CW Fractions

2.5. Qualitative Epitope Changes in CWs Produced by the Pph Inoculation and INA Priming

2.6. INA Priming Prevented Enzymatic Digestibility of CWs

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

4.2. Bacterial Strain and Growth Conditions

4.3. Elicitation, Pathogen Inoculation, and Sample Preparation

4.4. Reactive Oxygen Species Detection

4.5. Cell Wall Isolation

4.6. FTIR Spectroscopy

4.7. Sequential Polysaccharide Extraction

4.8. Cell Wall Sugar Content Analysis

4.9. Gel Permeation Chromatography

4.10. Immunodot Assays

4.11. Cell Wall Degradability

4.12. Statistical Analyses and Software

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dangl, J.L.; Horvath, D.M.; Staskawicz, B.J. Pivoting the plant immune system from dissection to deployment. Science 2013, 341, 746–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van Butselaar, T.; den Ackerveken, G. Salicylic Acid Steers the Growth-Immunity Tradeoff. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hématy, K.; Cherk, C.; Somerville, S. Host-pathogen warfare at the plant cell wall. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2009, 12, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacete, L.; Mélida, H.; Miedes, E.; Molina, A. Plant cell wall-mediated immunity: Cell wall changes trigger disease resistance responses. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2018, 93, 614–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaahtera, L.; Schulz, J.; Hamann, T. Cell wall integrity maintenance during plant development and interaction with the environment. Nat. Plants 2019, 5, 924–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zablackis, E.; Huang, J.; Müllerz, B.; Darvill, A.C.; Albersheim, P. Characterization of the Cell-Wall Polysaccharides of Arabidopsis Thaliana Leaves. Plant Physiol. 1995, 107, 1129–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carpita, N.; McCann, M. The cell wall. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Plants. 2000, 52–109. [Google Scholar]

- Mohnen, D. Pectin structure and biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2008, 11, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, M.; Yates, E.A.; Willats, W.G.T.; Martin, H.; Knox, J.P. Immunochemical comparison of membrane-associated and secreted arabinogalactan-proteins in rice and carrot. Planta 1996, 198, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, D.J. Growth of the plant cell wall. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 6, 850–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, J.; Ferraz, R.; Dupree, P.; Showalter, A.M.; Coimbra, S. Three Decades of Advances in Arabinogalactan-Protein Biosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedes, E.; Vanholme, R.; Boerjan, W.; Molina, A. The role of the secondary cell wall in plant resistance to pathogens. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vanholme, R.; De Meester, B.; Ralph, J.; Boerjan, W. Lignin biosynthesis and its integration into metabolism. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2019, 56, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredez, A.R.; Somerville, C.R.; Ehrhardt, D.W. Visualization of cellulose synthase demonstrates functional association with microtubules. Science 2006, 312, 1491–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, C.; Ganguly, A.; Baskin, T.I.; McClosky, D.D.; Anderson, C.T.; Foster, C.; Meunier, K.A.; Okamoto, R.; Berg, H.; Dixit, R. The fragile Fiber1 kinesin contributes to cortical microtubule-mediated trafficking of cell wall components. Plant Physiol. 2015, 167, 780–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.J.; Brandizzi, F. The plant secretory pathway for the trafficking of cell wall polysaccharides and glycoproteins. Glycobiology 2016, 26, 940–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chormova, D.; Messenger, D.J.; Fry, S.C. Boron bridging of rhamnogalacturonan-II, monitored by gel electrophoresis, occurs during polysaccharide synthesis and secretion but not post-secretion. Plant J. 2014, 77, 534–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stratilová, B.; Kozmon, S.; Stratilová, E.; Hrmova, M. Plant Xyloglucan Xyloglucosyl Transferases and the Cell Wall Structure: Subtle but Significant. Molecules 2020, 25, 5619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castilleux, R.; Plancot, B.; Vicré, M.; Nguema-Ona, E.; Driouich, A. Extensin, an underestimated key component of cell wall defence? Ann. Bot. 2021, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, A.; Miedes, E.; Bacete, L.; Rodríguez, T.; Mélida, H.; Denancé, N.; Sánchez-Vallet, A.; Rivière, M.P.; López, G.; Freydier, A.; et al. Arabidopsis cell wall composition determines disease resistance specificity and fitness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, C.; Karafyllidis, I.; Wasternack, C.; Turner, J.G. The Arabidopsis mutant cev1 links cell wall signaling to jasmonate and ethylene responses. Plant Cell 2002, 14, 1557–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hernández-Blanco, C.; Feng, D.X.; Hu, J.; Sánchez-Vallet, A.; Deslandes, L.; Llorente, F.; Berrocal-Lobo, M.; Keller, H.; Barlet, X.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, C.; et al. Impairment of cellulose synthases required for Arabidopsis secondary cell wall formation enhances disease resistance. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 890–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Benedictis, M.; Brunetti, C.; Brauer, E.K.; Andreucci, A.; Popescu, S.C.; Commisso, M.; Guzzo, F.; Sofo, A.; Ruffini Castiglione, M.; Vatamaniuk, O.K.; et al. The Arabidopsis thaliana Knockout Mutant for Phytochelatin Synthase1 (cad1-3) Is Defective in Callose Deposition, Bacterial Pathogen Defense and Auxin Content, But Shows an Increased Stem Lignification. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, Q.; Xiao, S.; Wang, X.; Ao, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, L. GhWRKY1-like enhances cotton resistance to Verticillium dahliae via an increase in defense-induced lignification and S monolignol content. Plant Sci. 2021, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallego-Giraldo, L.; Liu, C.; Pose-Albacete, S.; Pattathil, S.; Peralta, A.G.; Young, J.; Westpheling, J.; Hahn, M.G.; Rao, X.; Paul Knox, J.; et al. Arabidopsis dehiscence zone polygalacturonase 1 (ADPG1) releases latent defense signals in stems with reduced lignin content. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 3281–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reem, N.T.; Pogorelko, G.; Lionetti, V.; Chambers, L.; Held, M.A.; Bellincampi, D.; Zabotina, O.A. Decreased Polysaccharide Feruloylation Compromises Plant Cell Wall Integrity and Increases Susceptibility to Necrotrophic FungalPathogens. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bethke, G.; Thao, A.; Xiong, G.; Li, B.; Soltis, N.E.; Hatsugai, N.; Hillmer, R.A.; Katagiri, F.; Kliebenstein, D.J.; Pauly, M.; et al. Pectin biosynthesis is critical for cell wall integrity and immunity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 2015, 28, 537–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bacete, L.; Mélida, H.; López, G.; Dabos, P.; Tremousaygue, D.; Denancé, N.; Miedes, E.; Bulone, V.; Goffner, D.; Molina, A. Arabidopsis response reGUlator 6 (ARR6) modulates plant cell-wall composition and disease resistance. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2020, 33, 767–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogorelko, G.V.; Kambakam, S.; Nolan, T.; Foudree, A.; Zabotina, O.A.; Rodermel, S.R. Impaired chloroplast biogenesis in Immutans, an arabidopsis variegation mutant, modifies developmental programming, cell wall composition and resistance to Pseudomonas syringae. PLoS ONE 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Corpo, D.; Del Fullone, M.R.; Miele, R.; Lafond, M.; Pontiggia, D.; Grisel, S.; Kieffer-Jaquinod, S.; Giardina, T.; Bellincampi, D.; Lionetti, V. AtPME17 is a functional Arabidopsis thaliana pectin methylesterase regulated by its PRO region that triggers PME activity in the resistance to Botrytis cinerea. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2020, 21, 1620–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lionetti, V.; Fabri, E.; De Caroli, M.; Hansen, A.R.; Willats, W.G.T.; Piro, G.; Bellincampi, D. Three pectin methylesterase inhibitors protect cell wall integrity for arabidopsis immunity to Botrytis. Plant Physiol. 2017, 173, 1844–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lionetti, V.; Giancaspro, A.; Fabri, E.; Giove, S.L.; Reem, N.; Zabotina, O.A.; Blanco, A.; Gadaleta, A.; Bellincampi, D. Cell wall traits as potential resources to improve resistance of durum wheat against Fusarium graminearum. BMC Plant Biol. 2015, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ribot, C.; Hirsch, J.; Balzergue, S.; Tharreau, D.; Nottéghem, J.L.; Lebrun, M.H.; Morel, J.B. Susceptibility of rice to the blast fungus, Magnaporthe grisea. J. Plant Physiol. 2008, 165, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.-T.; Wang, B.-B.; Lecourieux, D.; Li, M.-J.; Liu, M.-B.; Liu, R.-Q.; Shang, B.-X.; Yin, X.; Wang, L.-J.; Lecourieux, F.; et al. Proteomic analysis of early-stage incompatible and compatible interactions between grapevine and P. viticola. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Tiedemann, A.; Koopmann, B.; Hoech, K. Lignin composition and timing of cell wall lignification are involved in Brassica napus resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum stem rot. Phytopathology 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macharia, T.N.; Bellieny-Rabelo, D.; Moleleki, L.N. Transcriptome profiling of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) responses to root-knot nematode (meloidogyne javanica) infestation during a compatible interaction. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauch-Mani, B.; Baccelli, I.; Luna, E.; Flors, V. Defense Priming: An Adaptive Part of Induced Resistance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2017, 68, 485–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kuć, J. Induced Immunity to Plant Disease. Bioscience 1982, 32, 854–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauss, H.; Theisinger-Hinkel, E.; Mindermann, R.; Conrath, U. Dichloroisonicotinic and salicylic acid, inducers of systemic acquired resistance, enhance fungal elicitor responses in parsley cells. Plant J. 1992, 2, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauss, H.; Franke, R.; Krause, K.; Conrath, U.; Jeblick, W.; Grimmig, B.; Matern, U. Conditioning of Parsley (Petroselinum crispum L.) Suspension Cells Increases Elicitor-Induced Incorporation of Cell Wall Phenolics. Plant Physiol. 1993, 102, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buswell, W.; Schwarzenbacher, R.E.; Luna, E.; Sellwood, M.; Chen, B.; Flors, V.; Pétriacq, P.; Ton, J. Chemical priming of immunity without costs to plant growth. New Phytol. 2018, 218, 1205–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ramírez-Carrasco, G.; Martínez-Aguilar, K.; Alvarez-Venegas, R. Transgenerational Defense Priming for Crop Protection against Plant Pathogens: A Hypothesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martínez-Aguilar, K.; Hernández-Chávez, J.L.; Alvarez-Venegas, R. Priming of seeds with INA and its transgenerational effect in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) plants. Plant Sci. 2021, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteagudo, A.B.; Rodiño, A.P.; Lema, M.; De La Fuente, M.; Santalla, M.; De Ron, A.M.; Singh, S.P. Resistance to infection by fungal, bacterial, and viral pathogens in a common bean core collection from the Iberian Peninsula. HortScience 2006, 41, 319–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arnold, D.L.; Lovell, H.C.; Jackson, R.W.; Mansfield, J.W. Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola: From “has bean” to supermodel. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2011, 12, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, A.M.; Godoy, L.; Santalla, M. Dissection of Resistance Genes to Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola in UI3 Common Bean Cultivar. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De la Rubia, A.G.; Centeno, M.L.; Moreno-González, V.; De Castro, M.; García-Angulo, P. Perception and first defense responses against Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola in Phaseolus vulgaris L.: Identification of Wall-Associated Kinase receptors. Phytopathology 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogliano, V.; Ballio, A.; Gallo, M.; Woo, S.; Scala, F.; Lorito, M. Pseudomonas lipodepsipeptides and fungal cell wall-degrading enzymes act synergistically in biological control. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. MPMI 2002, 15, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martínez-Aguilar, K.; Ramírez-Carrasco, G.; Hernández-Chávez, J.L.; Barraza, A.; Alvarez-Venegas, R. Use of BABA and INA As Activators of a Primed State in the Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kortekamp, A.; Zyprian, E. Characterization of Plasmopara-Resistance in grapevine using in vitro plants. J. Plant Physiol. 2003, 160, 1393–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebrowska, J.I. In vitro selection in resistance breeding of strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa duch.). Commun. Agric. Appl. Biol. Sci. 2010, 75, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tsiamis, G.; Mansfield, J.W.; Hockenhull, R.; Jackson, R.W.; Sesma, A.; Athanassopoulos, E.; Bennett, M.A.; Stevens, C.; Vivian, A.; Taylor, J.D.; et al. Cultivar-specific avirulence and virulence functions assigned to avrPphF in Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola, the cause of bean halo-blight disease. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 3204–3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebaque, D.; del Hierro, I.; López, G.; Bacete, L.; Vilaplana, F.; Dallabernardina, P.; Pfrengle, F.; Jordá, L.; Sánchez-Vallet, A.; Pérez, R.; et al. Cell wall-derived mixed-linked β-1,3/1,4-glucans trigger immune responses and disease resistance in plants. Plant J. 2021, 106, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Largo-Gosens, A.; Hernández-Altamirano, M.; García-Calvo, L.; Alonso-Simón, A.; Álvarez, J.; Acebes, J.L. Fourier transform mid infrared spectroscopy applications for monitoring the structural plasticity of plant cell walls. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kačuráková, M.; Capek, P.; Sasinková, V.; Wellner, N.; Ebringerová, A. FT-IR study of plant cell wall model compounds: Pectic polysaccharides and hemicelluloses. Carbohydr. Polym. 2000, 43, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.H.; Smith, A.C.; Kacuráková, M.; Saunders, P.K.; Wellner, N.; Waldron, K.W. The mechanical properties and molecular dynamics of plant cell wall polysaccharides studied by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. Plant Physiol. 2000, 124, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carpita, N.C.; Defernez, M.; Findlay, K.; Wells, B.; Shoue, D.A.; Catchpole, G.; Wilson, R.H.; McCann, M.C. Cell Wall Architecture of the Elongating Maize Coleoptile. Plant Physiol. 2001, 127, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, R.; Sugiyama, J. A combined FT-IR microscopy and principal component analysis on softwood cell walls. Carbohydr. Polym. 2003, 52, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekkal, M.; Dincq, V.; Legrand, P.; Huvenne, J.P. Investigation of the glycosidic linkages in several oligosaccharides using FT-IR and FT Raman spectroscopies. J. Mol. Struct. 1995, 349, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sene, C.; McCann, M.C.; Wilson, R.H.; Grinter, R. Fourier-Transform Raman and Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (An Investigation of Five Higher Plant Cell Walls and Their Components). Plant Physiol. 1994, 106, 1623–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rebaque, D.; Martínez-Rubio, R.; Fornalé, S.; García-Angulo, P.; Alonso-Simón, A.; Álvarez, J.M.; Caparros-Ruiz, D.; Acebes, J.L.; Encina, A. Characterization of structural cell wall polysaccharides in cattail (Typha latifolia): Evaluation as potential biofuel feedstock. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 175, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filisetti-Cozzi, T.M.C.C.; Carpita, N.C. Measurement of uronic acids without interference from neutral sugars. Anal. Biochem. 1991, 197, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.B.; Cosgrove, D.J. Xyloglucan and its interactions with other components of the growing cell wall. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 180–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, M.; Pahal, V.; Ahuja, D. Isolation and characterization of microfibrillated cellulose and nanofibrillated cellulose with “biomechanical hotspots”. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, E.M.; Fry, S.C. Pre-formed xyloglucans and xylans increase in molecular weight in three distinct compartments of a maize cell-suspension culture. Planta 2003, 217, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, M.; Martin, H.; Knox, J.P. An epitope of rice threonine- and hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein is common to cell wall and hydrophobic plasma-membrane glycoproteins. Planta 1995, 196, 510–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, J.P.; Linstead, P.J.; King, J.; Cooper, C.; Roberts, K. Pectin esterification is spatially regulated both within cell walls and between developing tissues of root apices. Planta 1990, 181, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.; Seymour, G.B.; Knox, J.P. Localization of Pectic Galactan in Tomato Cell Walls Using a Monoclonal Antibody Specific to (1 [->] 4)-β-D-Galactan. Plant Physiol. 1997, 113, 1405–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marcus, S.E.; Verhertbruggen, Y.; Hervé, C.; Ordaz-Ortiz, J.J.; Farkas, V.; Pedersen, H.L.; Willats, W.G.T.; Knox, J.P. Pectic homogalacturonan masks abundant sets of xyloglucan epitopes in plant cell walls. BMC Plant Biol. 2008, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zipfel, C.; Robatzek, S.; Navarro, L.; Oakeley, E.J.; Jones, J.D.G.; Felix, G.; Boller, T. Bacterial disease resistance in Arabidopsis through flagellin perception. Nature 2004, 428, 764–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinas, N.A.; Saze, H.; Saijo, Y. Epigenetic control of defense signaling and priming in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez-Prado, J.S.; Abulfaraj, A.A.; Rayapuram, N.; Benhamed, M.; Hirt, H. Plant Immunity: From Signaling to Epigenetic Control of Defense. Trends Plant Sci. 2018, 23, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, B.Q.; Guo, J.; Zhang, N.; Yao, X.; Wang, H.B.; Li, J.F. Cross-Microbial Protection via Priming a Conserved Immune Co-Receptor through Juxtamembrane Phosphorylation in Plants. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 26, 810–822.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hake, K.; Romeis, T. Protein kinase-mediated signalling in priming: Immune signal initiation, propagation, and establishment of long-term pathogen resistance in plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 904–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mélida, H.; Bacete, L.; Ruprecht, C.; Rebaque, D.; del Hierro, I.; López, G.; Brunner, F.; Pfrengle, F.; Molina, A. Arabinoxylan-Oligosaccharides Act as Damage Associated Molecular Patterns in Plants Regulating Disease Resistance. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mélida, H.; Sopeña-Torres, S.; Bacete, L.; Garrido-Arandia, M.; Jordá, L.; López, G.; Muñoz-Barrios, A.; Pacios, L.F.; Molina, A. Non-branched β-1,3-glucan oligosaccharides trigger immune responses in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2018, 93, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Driouich, A.; Follet-Gueye, M.-L.; Bernard, S.; Kousar, S.; Chevalier, L.; Vicré-Gibouin, M.; Lerouxel, O. Golgi-mediated synthesis and secretion of matrix polysaccharides of the primary cell wall of higher plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lionetti, V.; Cervone, F.; Bellincampi, D. Methyl esterification of pectin plays a role during plant-pathogen interactions and affects plant resistance to diseases. J. Plant Physiol. 2012, 169, 1623–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruano, G.; Scheuring, D. Plant Cells under Attack: Unconventional Endomembrane Trafficking during Plant Defense. Plants 2020, 9, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, N.; Sun, Y.; Pei, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, P.; Li, X.; Li, F.; Hou, Y. A pectin methylesterase inhibitor enhances resistance to verticillium wilt. Plant Physiol. 2018, 176, 2202–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferrari, S.; Sella, L.; Janni, M.; De Lorenzo, G.; Favaron, F.; D’Ovidio, R. Transgenic expression of polygalacturonase-inhibiting proteins in Arabidopsis and wheat increases resistance to the flower pathogen Fusarium graminearum. Plant Biol. 2012, 14 (Suppl. 1), 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, G.T.; Morris, E.R.; Rees, D.A.; Smith, P.J.C.; Thom, D. Biological interactions between polysaccharides and divalent cations: The egg-box model. FEBS Lett. 1973, 32, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Limberg, G.; Körner, R.; Buchholt, H.C.; Christensen, T.M.; Roepstorff, P.; Mikkelsen, J.D. Quantification of the amount of galacturonic acid residues in blocksequences in pectin homogalacturonan by enzymatic fingerprinting with exo- and endo-polygalacturonase II from Aspergillus niger. Carbohydr. Res. 2000, 327, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-C.; Bulgakov, V.P.; Jinn, T.-L. Pectin Methylesterases: Cell Wall Remodeling Proteins Are Required for Plant Response to Heat Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, L.; Hart, B.E.; Khan, G.A.; Cruz, E.R.; Persson, S.; Wallace, I.S. Associations between phytohormones and cellulose biosynthesis in land plants. Ann. Bot. 2020, 126, 807–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Valle, A.; López-Calleja, A.C.; Alvarez-Venegas, R. Enhancement of Pathogen Resistance in Common Bean Plants by Inoculation With Rhizobium etli. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincken, J.P.; Schols, H.A.; Oomen, R.J.F.J.; McCann, M.C.; Ulvskov, P.; Voragen, A.G.J.; Visser, R.G.F. If homogalacturonan were a side chain of rhamnogalacturonan I. Implications for cell wall architecture. Plant Physiol. 2003, 132, 1781–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tang, W.; Li, A.-Q.; Yin, J.-Y.; Nie, S.-P. Structural characteristics of three pectins isolated from white kidney bean. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Angulo, P.; Willats, W.G.T.; Encina, A.E.; Alonso-Simón, A.; Álvarez, J.M.; Acebes, J.L. Immunocytochemical characterization of the cell walls of bean cell suspensions during habituation and dehabituation to dichlobenil. Physiol. Plant. 2006, 127, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encina, A.; Sevillano, J.M.; Acebes, J.L.; Alvarez, J. Cell wall modifications of bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) cell suspensions during habituation and dehabituation to dichlobenil. Physiol. Plant. 2002, 114, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, D.J. Plant cell wall extensibility: Connecting plant cell growth with cell wall structure, mechanics, and the action of wall-modifying enzymes. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepak, S.; Shailasree, S.; Kini, R.K.; Muck, A.; Mithöfer, A.; Shetty, S.H. Hydroxyproline-rich Glycoproteins and Plant Defence. J. Phytopathol. 2010, 158, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnich, E.; Bjarnholt, N.; Eudes, A.; Harholt, J.; Holland, C.; Jørgensen, B.; Larsen, F.H.; Liu, M.; Manat, R.; Meyer, A.S.; et al. Phenolic cross-links: Building and de-constructing the plant cell wall. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2020, 37, 919–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Shirsat, A.H. Extensin over-expression in Arabidopsis limits pathogen invasiveness. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2006, 7, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiré, C.; De Rycke, R.; De Loose, M.; Inzé, D.; Van Montagu, M.; Engler, G. Extensin gene expression is induced by mechanical stimuli leading to local cell wall strengthening in Nicotiana plumbaginifolia. Planta 1994, 195, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkouropoulos, G.; Shirsat, A.H. The unusual Arabidopsis extensin gene atExt1 is expressed throughout plant development and is induced by a variety of biotic and abiotic stresses. Planta 2003, 217, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merkouropoulos, G.; Barnett, D.C.; Shirsat, A.H. The Arabidopsis extensin gene is developmentally regulated, is induced by wounding, methyl jasmonate, abscisic and salicylic acid, and codes for a protein with unusual motifs. Planta 1999, 208, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hückelhoven, R. Cell Wall–Associated Mechanisms of Disease Resistance and Susceptibility. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2007, 45, 101–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betsuyaku, S.; Katou, S.; Takebayashi, Y.; Sakakibara, H.; Nomura, N.; Fukuda, H. Salicylic Acid and Jasmonic Acid Pathways are Activated in Spatially Different Domains around the Infection Site during Effector-Triggered Immunity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018, 59, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero, V.; Torres, M.Á.; Delgado, M.; Sopeña-Torres, S.; Swami, S.; Morales, J.; Muñoz-Barrios, A.; Mélida, H.; Jones, A.M.; Jordá, L.; et al. Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase 1 (MKP1) negatively regulates the production of reactive oxygen species during Arabidopsis immune responses. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2019, 32, 464–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020; ISBN 3900051070. [Google Scholar]

- Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. FactoMineR: An R package for multivariate analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Updegraff, D.M. Semimicro determination of cellulose inbiological materials. Anal. Biochem. 1969, 32, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeman, J.F.; Moore, W.E.; Millet, M.A. Sugar units present. Hydrolysis and quantitative paper chromatography. Methods Carbohydr. Chem. 1963, 3, 54–69. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric Method for Determination of Sugars and Related Substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenkrantz, N.; Asboe-Hansen, G. New method for quantitative determination of uronic acids. Anal. Chem. 1973, 5, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albersheim, P.; Nevins, D.J.; English, P.D.; Karr, A. A method for the analysis of sugars in plant cell-wall polysaccharides by gas-liquid chromatography. Carbohydr. Res. 1967, 5, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, M.; Largo-Gosens, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; García-Angulo, P.; Acebes, J.L. Early cell-wall modifications of maize cell cultures during habituation to dichlobenil. J. Plant Physiol. 2014, 171, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Wavenumber (cm−1) | Cos2 Dim2 | CW Component | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 808–816 | 8.05 × 10−1–6.93 × 10−1 | Unknown | |

| 1148 | 7.14 × 10−1 | RG-I, Galactan, Xyloglucan | [55] |

| 1152 | 7.98 × 10−1 | RG-I, Galactan, Xyloglucan | [55] |

| 1156 | 7.18 × 10−1 | Arabinogalactan | [55] |

| 1160 | 6.90 × 10−1 | Cellulose | [56,57] |

| 1164 | 7.39 × 10−1 | Cellulose | [58] |

| 1192–1196 | 6.43 × 10−1–7.26 × 10−1 | Unknown | |

| 1200 | 7.61 × 10−1 | C = CH | [59] |

| 1204–1228 | 7.98 × 10−1–8.12 × 10−1 | Unknown | |

| 1232 | 8.02 × 10−1 | Pectin | [60] |

| 1236–1240 | 7.72 × 10−1–7.26 × 10−1 | Unknown | |

| 1244 | 6.67 × 10−1 | Pectin | [59] |

| 1472–1596 | 6.61 × 10−1–6.14 × 10−1 | Unknown | |

| 1616 | 7.34 × 10−1 | Free carboxyl uronic acid | [55] |

| 1620 | 7.15 × 10−1 | Free carboxyl uronic acid | [60] |

| 1624 | 6.89 × 10−1 | Free carboxyl uronic acid | [60] |

| 1628 | 7.24 × 10−1 | Free carboxyl uronic acid | [60] |

| 1632 | 7.41 × 10−1 | Phenolic ring | [60] |

| 1636–1648 | 7.57 × 10−1–6.35 × 10−1 | Unknown | |

| 1720 | 6.09 × 10−1 | Phenolic ester | [57,60] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De la Rubia, A.G.; Mélida, H.; Centeno, M.L.; Encina, A.; García-Angulo, P. Immune Priming Triggers Cell Wall Remodeling and Increased Resistance to Halo Blight Disease in Common Bean. Plants 2021, 10, 1514. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/plants10081514

De la Rubia AG, Mélida H, Centeno ML, Encina A, García-Angulo P. Immune Priming Triggers Cell Wall Remodeling and Increased Resistance to Halo Blight Disease in Common Bean. Plants. 2021; 10(8):1514. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/plants10081514

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe la Rubia, Alfonso Gonzalo, Hugo Mélida, María Luz Centeno, Antonio Encina, and Penélope García-Angulo. 2021. "Immune Priming Triggers Cell Wall Remodeling and Increased Resistance to Halo Blight Disease in Common Bean" Plants 10, no. 8: 1514. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/plants10081514