Input Issues in the Development of L2 French Morphosyntax

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Linguistic Factors and Input Characteristics

3. French Verb Morphology

| (1) | Infinitive | Present Singular | 2nd Present Plural | Past Participle | Future Tense |

| tenir ‘hold’ | tiens/t | tenez | tenu | tiendrai | |

| venir ‘come’ | viens/t | venez | venu | viendrai |

- The four very irregular and frequent verbs être ‘be,’ avoir ‘have,’ aller ‘go,’ and faire ‘do.’ These verbs are characterized by a high token frequency. Their paradigms consist of many suppletive forms but also of some regularities (see Table 2). They are all used as auxiliaries (faire in very specific contexts as in se faire couper les cheveux ‘get a haircut’), and all of them are semantically very open or at least polysemous (for example the usage of aller as ‘go’ and ‘be [fine]’). Constructions with faire can describe most actions and replace action verbs (faire un plongeon ‘take a dive,’ plonger ‘dive’).

- The regular verbs ending in -er in the infinitive (parler ‘speak’). This is the most regular and productive verb conjugation. Its pattern is very high in type frequency: 90% of French verbs follow this pattern (more than 6000 verbs according to le conjugueur). The domination of these verbs in the French verbal system has many implications for the learners’ interlanguage, as we will see in the next section.

- The other verbs. As discussed above, there are patterns of regularity in this group of verbs; however, compared to the pattern of the -er verbs, they are quite low in type frequency. This makes most of these verbs generally low in both type and token frequency.

4. Effects of French Input and the Development of L2 French Verb Morphology

4.1. Default Forms in L2 Spoken French

| (2) | a. | elle mange |

| ‘she eats’ present tense context—correct | ||

| b. | les hommes va parle | |

| ‘the men will speaks’ infinitive context—incorrect | ||

| c. | il dans[e] | |

| ‘he dance’ present tense context—incorrect | ||

| d. | deux personnes va voyag[e] | |

| ‘two people will travel’ infinitive context—correct |

- Data from the French database C-ORAL-ROM (Cresti and Moneglia 2005);

- Data from adult native speakers of French in conversation with adult classroom learners of L2 French (4 recordings of 60′ each and 25 recordings of 20–30′ each);

- Thirty-nine recordings of classroom teaching (Flyman Mattsson 2003);

- One textbook used at beginner level.

| (3) | Stimulus | 9 | En France | Carl | habite | au bord de la mer. | |

| in France | Carl | lives | at the seaside | ||||

| P24 | A la France | Carl | habite | près de la mer | |||

| Stimulus | 10 | En mars | Marie | veut | habiter | à Paris. | |

| in March | Marie | wants | to live | in Paris | |||

| P24 | A mars | Carl | habite | à Paris |

| (4) | Stimulus | 2 | Aujourd’hui | Christine | veut | acheter | une robe. |

| today | Christine | wants | to buy | a dress | |||

| P16 | Aujourd’hui | Marie | achetE | une robe | |||

| Stimulus | 1 | Au supermarché | Carl | achète | un melon. | ||

| at the supermarket | Carl | buys | a melon | ||||

| P16 | A supermarché | Carl | achetE | un melon |

| (5) | Stimulus | 14 | Maintenant | Marie | veut | parler | avec son chef. |

| now | Marie | wants | to speak | with her boss | |||

| P26 | Maintenant | Marie | va | parle | avec son chef | ||

| P08 | Maintenant | Carine | va | parler | avec son chef | ||

| Stimulus | 13 | Au travail | Carl | parle | avec une collègue | ||

| at work | Carl | speaks | with a colleague | ||||

| P26 | Au travail | Carl | parle | au une collègue | |||

| P08 | Au travail | Carl | parle | avec une collègue |

4.2. The Development of Third Person Plural Forms

- Identical: il danse ‘he dances’; ils dansent ‘they dance’; il voit ‘he sees’; ils voient ‘they see’ (-er verbs and some irregular verbs)

- Perceivable difference through a liaison in the plural: il arrive ‘he arrives’; ils arrivent ‘they arrive’

- Suppletive forms: only the four highly frequent verbs (être, avoir, faire, and aller)

- Irregular verbs with stem alternation: il prend ‘he takes’; ils prennent ‘they take’; il dit ‘he says’; ils disent ‘they say.’

4.3. The Development of Past Tense

- The adult interlocutors (MOT, CHR, FAT, MAD) in interaction with the L1 child Philippe aged from 2.1 to 3.3 years (corpus Leveille, 26 recordings) and the L1 child Grégoire aged from 1.9 to 2.5 years (corpus Champaud, 33 recordings) in CHILDES (MacWhinney 2002).

- The adult interlocutors in conversation with five children learning L2 French in immersion in Sweden (Ågren et al. 2014), 27 recordings of 20–30′ each.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ågren, Malin. 2017. Étude expérimentale sur le traitement de l’accord sujet-verbe en nombre en FLE. Bulletin suisse de Linguistique appliquée 105: 69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ågren, Malin, and Joost van de Weijer. 2013. Input Frequency and the Acquisition of Subject-Verb Agreement in Number in Spoken and Written French. Journal of French Language Studies 23: 311–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ågren, Malin, Jonas Granfeldt, and Anita Thomas. 2014. Combined Effects of Age of Onset and Input on the Development of Different Grammatical Structures. A Study of Simultaneous and Successive Bilingual Acquisition of French. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 4: 462–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, Roger W. 2002. The Dimensions of “Pastness”. In The L2 Acquisition of Tense-Aspect Morphology. Edited by R. Salaberry and Yasuhiro Shirai. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 70–105. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, Roger W., and Yasuhiro Shirai. 1994. ‘Discourse Motivations for Some Cognitive Acquisition Principles’. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 16: 133–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, Michael, and Suzanne Kemmer. 2000. Introduction: A Usage-Based Conception of Language. In Usage Based Models of Language. Edited by Michael Barlow and Suzanne Kemmer. Stanford: CSLI Publications, pp. vii–xxviii. [Google Scholar]

- Bartning, Inge, and Suzanne Schlyter. 2004. Itinéraires Acquisitionnels et Stades de Développement En Français L2. Journal of French Language Studies 14: 281–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bartning, Inge, Fanny Forsberg, and Victorine Hancock. 2009. Resources and Obstacles in Very Advanced L2 French: Formulaic Language, Information Structure and Morphosyntax. EUROSLA Yearbook 9: 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, Heike, and Stefan Pfänder. 2016. Experience Counts Frequency Effects in Language Acquisition, Language Change, and Language Processing. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Boulton, Alex. 2017. Corpora in Language Teaching and Learning. Language Teaching 50: 483–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, Joan L. 1995. Regular Morphology and the Lexicon. Language and Cognitive Processes 10: 425–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, Joan L. 2008. Usage-Based Grammar and Second Language Acquisition. In Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics and Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Peter Robinson and Nick C. Ellis. New York: Routledge, pp. 216–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cadierno, Teresa, and Søren Wind Eskildsen, eds. 2015. Usage-Based Perspectives on Second Language Learning. Applications of Cognitive Linguistics 30. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Laura, Pavel Trofimovich, Joanna White, Walcir Cardoso, and Marlise Horst. 2009. ‘Some Input on the Easy/Difficult Grammar Question: An Empirical Study’. Modern Language Journal 93: 336–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresti, Emanuela, and Massimo Moneglia. 2005. C-ORAL-ROM: Integrated Reference Corpora for Spoken Romance Languages. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Dimroth, Christine. 2018. ‘Beyond Statistical Learning: Communication Principles and Language Internal Factors Shape Grammar in Child and Adult Beginners Learning Polish Through Controlled Exposure’. Language Learning 68: 863–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Nick C. 2006. Selective Attention and Transfer Phenomena in L2 Acquisition: Contingency, Cue Competition, Salience, Interference, Overshadowing, Blocking, and Perceptual Learning. Applied Linguistics 27: 164–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Nick C., Ute Römer, and Matthew Brook O’Donnell. 2016. Usage-Based Approaches to Language Acquisition and Processing: Cognitive and Corpus Investigations of Construction Grammar. Chichester: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Fayol, Michel, and Jean-Pierre Jaffré. 2008. Orthographier. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- Flyman Mattsson, Anna. 2003. Teaching, Learning, and Student Ouput. A Study of French in the Classroom. Ph.D. Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- Gass, Susan M. 2015. Comprehensible Input and Output in Classroom Interaction. In The Handbook of Classroom Discourse and Interaction. Edited by Numa Markee. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Inc, pp. 182–97. [Google Scholar]

- Giroud, Anick, and Christian Surcouf. 2016. De «Pierre, combien de membres avez-vous?» à «Nous nous appelons Marc et Christian»: Réflexions autour de l’authenticité dans les documents oraux des manuels de FLE pour débutants. SHS Web of Conferences 27: 07017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goldschneider, Jennifer M., and Robert M. DeKeyser. 2001. Explaining the “Natural Order of L2 Morpheme Acquisition” in English: A Meta-Analysis of Multiple Determinants. Language Learning 51: 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, Martin. 2011. Input Perspectives on the Role of Learning Context in Second Language Acquisition. An Introduction to the Special Issue. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching 49: 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprowicz, Rowena, and Emma Marsden. 2018. Towards Ecological Validity in Research into Input-Based Practice: Form Spotting Can Be as Beneficial as Form-Meaning Practice. Applied Linguistics 39: 886–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihlstedt, Maria, and Suzanne Schlyter. 2009. Emploi de La Morphologie Temporelle En Français L2 : Étude Comparative Auprès d’enfants Monolingues et Bilingues de 8 à 9 Ans. Acquisition et Interaction En Langue Étrangère AILE 1: 89–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labeau, Emmanuelle. 2005. Beyond the Aspect Hypothesis: Tense–Aspect Development in Advanced L2 French. EUROSLA Yearbook 5: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacWhinney, Brian. 2002. The CHILDES Project: Tools for Analyzing Talk. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Madlener, Karin. 2018. Do Findings from Artificial Language Learning Generalize to Second Language Classrooms? In Usage-Inspired L2 Instruction. Researched Pedagogy. Edited by Andrea E. Tyler, Lourdes Ortega, Mariko Uno and Hae In Park. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 211–34. [Google Scholar]

- Meunier, Fanny, and William Marslen-Wilson. 2004. Regularity and Irregularity in Frenchverbal Inflection. Language and Cognitive Processes 19: 561–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nicoladis, Elena, Andrea Palmer, and Paula Marentette. 2007. The Role of Type and Token Frequency in Using Past Tense Morphemes Correctly. Developmental Science 10: 237–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paradis, Johanne. 2010. Bilingual Children’s Acquisition of English Verb Morphology: Effects of Language Exposure, Structure Complexity, and Task Type. Language Learning 60: 651–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, Johanne, Elena Nicoladis, Martha Crago, and Fred Genesee. 2011. Bilingual Children’s Acquisition of the Past Tense: A Usage-Based Approach. Journal of Child Language 38: 554–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perdue, Clive, ed. 1993. Adult Language Acquisition: Cross-Linguistic Perspectives. Volume 2. The Results. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prévost, Philippe. 2009. The Acquisition of French. In The Development of Inflectional Morphology and Syntax in L1 Acquisition, Bilingualism, and L2 Acquisition. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Prévost, Philippe, and Lydia White. 2000. Missing Surface Inflection or Impairment in Second Language Acquisition? Evidence from Tense and Agreement. Second Language Research 16: 103–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, Naoki. 2019. Profiling Vocabulary for Proficiency Development: Effects of Input and General Frequencies on L2 Learning. System 87: 102167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, Richard. 2001. Attention. In Cognition and Second Language Instruction. Edited by Peter Robinson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Anita. 2009. Les Apprenants Parlent-Ils à l’infinitif? Influence de l’input Sur La Production Des Verbes Par Des Apprenants Adultes Du Français. Études romanes de Lund 87. Lund: Lund University (Sweden). Available online: http://lup.lub.lu.se/search/ws/files/5369358/1473802.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Thomas, Anita. 2014a. C’est La Faute de l’input! Fréquence Des Formes et Biais Distributionnels. Presented at the The Expression of Temporality by L2 Learners of French and English, Acquisition of Time, Aspect, Modality, Montpellier, France, May 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Anita. 2014b. Le Rôle de l’Aspect Lexical et de la Fréquence des Formes dans l’Input sur la Production des Formes du Passé par des Enfants Apprenants du Français L2 en Début d’Acquisition. The Canadian Modern Language Review/La Revue Canadienne Des Langues Vivantes 70: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Anita, and Annelie Ädel. 2021. Input. In The Routledge Handbook of Second Language Acquisition and Corpor. Edited by Nicole Tracy-Ventura and Magali Paquot. New York: Routledge, pp. 267–79. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, Henriette. 1982. Enquête Phonologique et Variétés Régionales Du Français. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Les groupes sont un bon moyen de catégoriser les verbes pour retenir plus facilement leurs terminaisons. |

| 2 | Since the research question was concerned with the form produced regardless of the syntactic context, the syntactic match with the form was disregarded. Nevertheless, 87% of the present tense forms were produced in the syntactic context for such a form as opposed to only 37% of the forms in [e]. |

| Regular -ir | Irregular -ir | ||||

| infinitive | 2nd present plural | past participle | infinitive | 2nd present plural | past participle |

| asservir ‘enslave’ | asservissez | asservi | servir ‘serve’ | servez | servi |

| répartir ‘distribute’ | répartissez | réparti | partir ‘leave’ | partez | parti |

| ressortir ‘coming from’ | ressortissez | ressorti | ressortir ‘go out again’ | ressortez | ressorti |

| Infinitive | Imparfait Stem | and Endings | Future Stem | and Endings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| être ‘be’ faire ‘do’ parler ‘speak’ partir ‘leave’ répartir ‘distribute’ vendre ‘sell’ prendre ‘take’ voir ‘see’ boire ‘drink’ | ét- fais parl- part- répartiss- vend- pren- voy- buv- | -ais -ais -ait -ions -iez -aient | ser- fer- parler- partir- répartir- vendr- prendr- verr- boir- | -ai -as -a -ons -ez -ont |

| Tense | Regular -er Verbs /Spoken/ and Written Forms | Irregular Verbs (Example) /Spoken/ and Written Forms |

|---|---|---|

| present singular je, tu, il/elle, on ‘I, you, s/he, one’ | /dɔn/ donne/s/nt ’give(s)’ | /li/ lis/lit ‘read(s)’ |

| present 3rd plural ils/elles ‘they’ | /liz/ lisent ‘read’ | |

| present 2nd plural vous ‘you’ | /dɔne/ donnez ‘give’ | /lize/ lisez ‘read’ |

| infinitive | /dɔne/ donner ‘to give’ | /liʁ/ lire ‘to read’ |

| past participle | /dɔne/ donné ‘(have) given’ | /ly/ lu ‘(have) read’ |

| imparfait | /dɔne/ /dɔnε/ donnais… ‘gave’ | /lize/ /lizε/ lisais… ‘read’ |

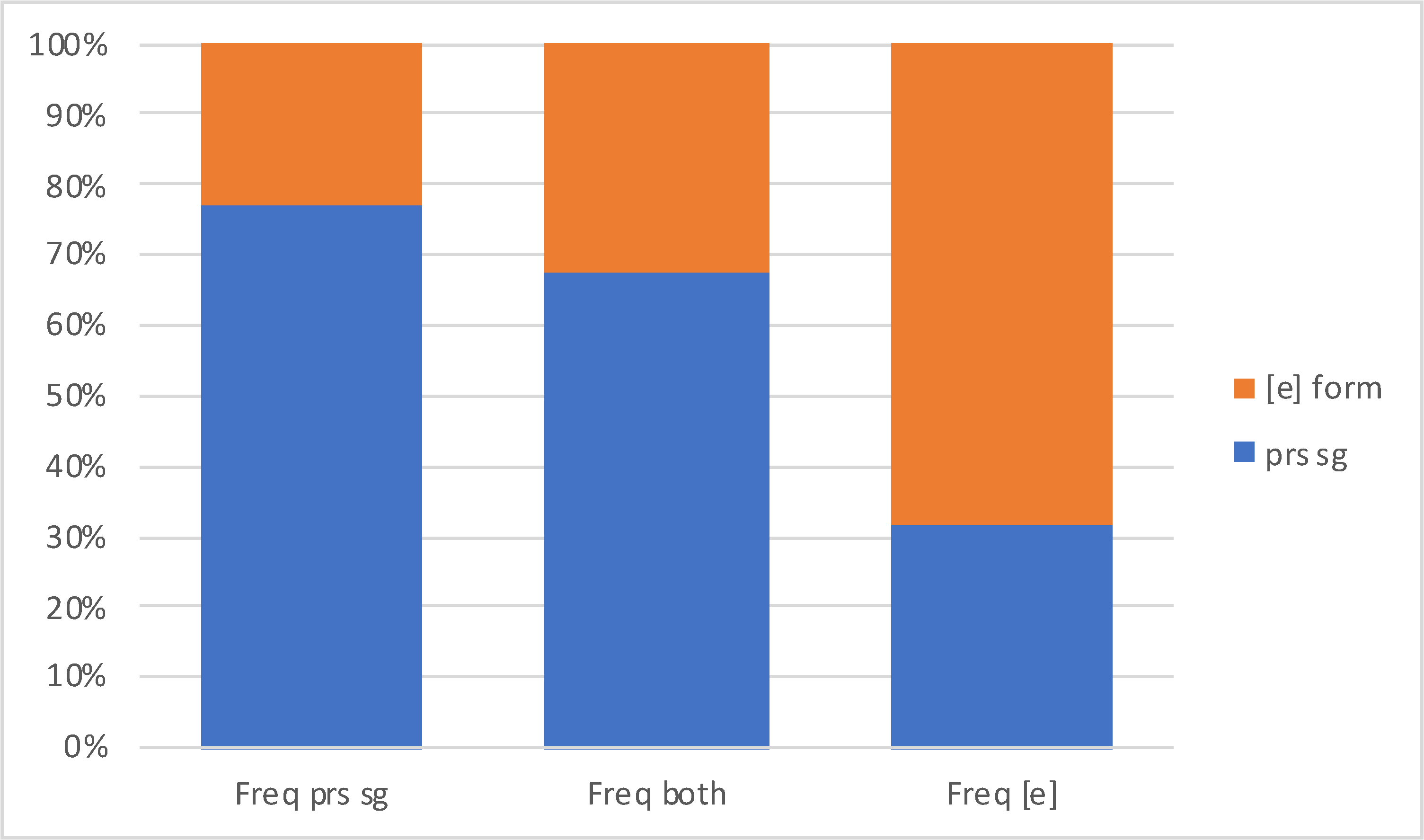

| Verbs | Expected form Based on Lexical Aspect | Expected form Based on Input Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Stative verbs frequent in present tense sg and 3rd pl adorer, penser, habiter, détester, préférer, aimer (trouver) | present tense (short form) | present tense (short form) |

| Dynamic verbs frequent in both forms trouver, regarder, parler, manger | form ending in [e] (long form) | variation (both forms) |

| frequent in the form ending in [e] acheter, visiter | form ending in [e] (long form) |

| Context | Regular -er Verbs Proportion (Tokens) | Irregular Verbs Proportion (Tokens) |

|---|---|---|

| Present sg+3pl | 48% (2950) | 60% (7124) |

| Infinitive | 23% (1445) | 16% (1922) |

| Present 2nd plural | 5% (324) | 5% (542) |

| imparfait | 6% (372) | 5% (630) |

| Past participle | 18% (1110) | 14% (1655) |

| Sum forms ending in [e] (grey zone) | 52% (3251) | 10% (1172) |

| Sum | 6201 | 11,873 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thomas, A. Input Issues in the Development of L2 French Morphosyntax. Languages 2021, 6, 34. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/languages6010034

Thomas A. Input Issues in the Development of L2 French Morphosyntax. Languages. 2021; 6(1):34. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/languages6010034

Chicago/Turabian StyleThomas, Anita. 2021. "Input Issues in the Development of L2 French Morphosyntax" Languages 6, no. 1: 34. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/languages6010034