1. Introduction

Running one’s own business is arduous but not unachievable in the developing world. Although, there are limited resources and a number of obstacles to actualize the decided goals. Even though, establishing its own business would be advantageous since it mitigates issues of poverty and also enhances the standard of living. Global Entrepreneurship

Monitor’s (

2017) report stated that total early-stage entrepreneur activity increased by 10% in the last two decades.

Rashid and Ratten (

2020) highlighted that entrepreneur skills had contributed tremendously to the economy. Similarly,

Sajjad et al. (

2020) addressed the input of female entrepreneurs globally that is still not regarded as it should be and not given attention, but is a significant benefactor for economic development.

On contrary, the participation of women in the national economy is still very low. Strong patriarchal notions envelop cultural, social, religious, economic and political spheres that eventually result in the punier social standing of women in the society. Women are often discouraged to take independent decisions including starting a business (

Salahuddin et al. 2021). Currently, it is also observed that entrepreneurship is a key driver of economic progress and improvement in a country as it generates employment, raises living standards, and alleviates poverty. Moreover, globalization and societal development have witnessed women playing a crucial role in uplifting the economy. Although, they make uncountable efforts to serve their economy like men, regardless due to certain factors, they underperform (

Zeb and Ihsan 2020).

Hence, WEDs (Female Entrepreneurship Development System) developed by NPO (National Productivity Organization) enhance women’s innovative entrepreneurship competency from home business to commercial ventures and assists them to begin with their own business. According to their report, women entrepreneurship (WE) and empowerment have played a vital role in social and economic development—approximately 48% of Pakistan’s total population represents women and about 21% demonstrates women employment in different sectors of the economy.

Pakistani women executing their business has witnessed a boom in recent years. Their work has made a substantial impact on economic and social growth. However, their businesses are smaller in size and earn less profit as compared to the men entrepreneurs (

Shakeel et al. 2020). Similarly,

Baporikar and Akino (

2020) highlights that women, owing their enterprises, have become essential to the economic expansion because it helps in alleviating poverty, reduces gender inequality, and demonstrates productive work. According to them, the highest ratio in the business world is mostly owned by women. Thus, women should be subsidized by government bodies to get financial training from different training institutions because financial knowledge and learning is an intangible asset that helps people to gain a competitive advantage in their field. For instance, the IBA (Institute of Business Administration) won “The Outstanding Specialty Entrepreneurship Program Award” rewarded by the United States Association for Small Business and Entrepreneurship (USASBE) in 2017. Hence, other institutions built by government should also contribute more to it.

Corresponding to the current study,

Soomro et al. (

2020) investigated the perceptions of fresh entrepreneurs who aspire to attain sustainable business in Pakistan. On the contrary,

Dwyer et al. (

2002);

Bannier and Neubert (

2016) investigated men’s and women’s entrepreneurship investment behavior.

Niethammer et al. (

2007) stated that Carmen Niethammer, a program manager GEM (Gender Entrepreneurship Markets), initiated an International Finance Corporation (IFC), Private Enterprise Partnership that facilitates the Middle East and North Africa (PEP-MENA facility). It is based in Cairo, Egypt, and heads the team that offers technical support solutions for growth-oriented small and medium women enterprises. It also makes aware of women contribution in economic activities. Thus, their motive is to provide financial training so that they can run successful businesses because women are considered appealing customers to relationship managers in banks. These managers very well understand the requirements and psychology of the investment party and in return, offer them adequate solutions (

Paluri and Mehra 2016). The authors emphasize that approaches to provide investment solutions for women are not yet evolved. Thus, financial planners need to understand the investment goals, emotions, mode of communication, and decision process. This will eventually assist financial organizers and relationship managers to well-prepare themselves to interact with female entrepreneurs as investors and become their partners to complete their voyage of growth.

Kappal and Rastogi (

2020) pointed out that there is a wide scope for primary research to examine the attitude of the investor’s decision process. Thus, there is a dearth of exploitation, investigation, and exploration to find the investment attitude of the women owning businesses.

Oppedal

Berge and Garcia Pires (

2020) empirically observed the investment methods employed by women. Moreover,

Dwyer et al. (

2002);

Charness and Gneezy (

2012) reported that women invest less than men and they possess a risk-averse attitude in general. Psychologically,

Barber and Odean (

2001);

Mishra and Metilda (

2015) discovered that men are more overconfident as compared to women. Consequently, proves that men indulge more in financial transactions than women because females depict risk-averse behavior as well as tend to hold long-term investments. This eventually results in limited financial knowledge on the part of women (

Lusardi and Mitchell 2008). According to

Farrell et al. (

2016) adequate timely financial knowledge to women will motivate them to invest diversely.

Kumar et al. (

2018) asserted that males take more interest in financial matters and gender affects rational decision making, which does not affect the anxiety of money and concern for sufficient saving for a later period. On the contrary,

Trevelyan (

2008) identified that gender is not the point of focus because according to him optimistic entrepreneurs are capable of letting go of uncertainty they focus on upcoming good circumstances. They tend to evaluate situations to magnify the strengths, focus on opportunities, and demote weaknesses and threats in their work.

This study also contributes to studies of women’s investment behavior. Women entrepreneurs are focused because in existing challenging world they are actively competing and participating in different financial decisions. They differ from men in their investment behavior. Moreover, different private and government institutions are stepping ahead to promote women in executing their business.

The reasons behind this research is to study women gradual participation in financial decision-making for their families. Secondly, men and women’s opponent financial behavior moreover, the role of Pakistani institution stepping ahead to grow women market. Thus, to study the increasing number of female entrepreneurs, it is essential to study their attributes towards investment. However, knowledge of the financial market or financial learning better helps to study female entrepreneurs. Moreover, policymakers, investment consultants, and different scholars will better understand Pakistani women’s business owners through interview-based responses. This study aims to determine the influencing factors of Pakistani female entrepreneurs and to identify the behavior of Pakistani female entrepreneurs making investment decisions. The study took place in Karachi and Lahore which are the start-up hubs in Pakistan. Furthermore, this study interviewed 18 female entrepreneurs and employed a qualitative research tool for an in-depth interview.

2. Literature Review

Investment behaviors of men and women vary in several ways. Thus, this difference in investment behavior has augmented the scope of research in the context of behavioral finance. Similarly,

Kappal and Rastogi (

2020) also argued that individual investment behavior is affected by personality, gender difference, socio-economic environment, attitudes, myths, and other demographic info. The prevailing literature separately identifies female entrepreneur behavioral and psychological attributes that influence investment attitude in the context of Pakistan. This will ultimately help the financial service industry to offer adequate investment opportunities.

According to,

Kahneman and Tversky (

1979), prospect theory contributed a lot in the domain of behavioral finance to attain growth and development. It was found that during uncertain conditions, investor’s attitudes deviate from the results proposed by the economic theory.

Ritter (

2003) proposed that behavioral finance employs models that encompass some agents that are not completely rational, either they differ in preferences or demonstrate wrong beliefs. Behavioral finance embraces that, in certain conditions, a financial market is inefficient. Moreover, behavioral finance determines and infer reasons behind individual investment attitudes that eventually assist in understanding the change in prices and also positioning various investment varieties in the financial market. Hence, behavioral finance can be comprehensively studied considering rational and irrational investment behavior. Secondly, the anomalies in the efficient market proposing hypothesis to explicitly elaborate behavioral models (

Pompian 2006).

To determine the investment attitude of an individual, it is essential to understand that this behavior is determined through their financial knowledge and mathematics expertise. Thus, Khresna

Brahmana et al. (

2012) recommended modern finance-theory which demonstrates market efficiency is determined not only through the gen adjusted acceleration but through the existing information in the market. This suggests that asset prices include all information and estimations of the true-value through the passage of time. Hence, this incorporation authenticates the assumption of rational behavior. Similarly,

Nigam et al. (

2018);

Kumar et al. (

2018);

Baker et al. (

2018);

Chavali and Mohanraj (

2016) identified many other factors affecting the investor’s financial decision process. According to them, humans fail to make rational decisions every time because they often make biased decisions depending on their attributes, gender, fund utilization, and other financial activities. They argue that individuals, while making financial decisions, are heavily affected by recurring market sentiments and their personal emotions and attitudes.

The current literature illustrates social influences, personal influences, behavioral influencing biases, and the level of financial knowledge, investment experiences, levels of optimistic behavior, and ability to resist uncertainty while making decisions to invest in any asset or engage in financial activity maintaining their entrepreneurial portfolio.

Fisher and Statman (

2000);

Kumar and Goyal (

2015); Kleinübing

GoDoi et al. (

2005) argue that investors make biased decisions that lead them to make irrational decisions while performing investment activities. Moreover, Kleinübing

GoDoi et al. (

2005) emphasized that cognitive biases derive from flawed reasoning that originate due to limited time, knowledge, and lack of attention. Correspondingly,

Fisher and Statman (

2000) identified the overconfidence bias of the investors who overestimate their capabilities of judgment. Similarly,

Trevelyan (

2008) argued that optimism found in entrepreneurs always produces constructive consequences in improving health, reducing stress, and coping with occurring uncertain challenges in the business.

Litt et al. (

1992) in their studies, also promoted the optimistic behavior of entrepreneurs. According to them, optimism promotes persistence and commitment. Moreover,

McColl-Kennedy and Anderson (

2005) asserted optimism enables entrepreneurs to retain their subordinates in the venture.

Barber and Odean (

2001) stated that optimistic entrepreneurs discourage any negative info about a stock. On contrary, anchoring bias prevails when the tendency to an immaterial number is considered as references (

Fisher and Statman 2000). Availability bias arises when investors relate the most prevailing and familiar results instead of statistically plausible outcomes (

Pompian 2006).

Mishra and Metilda (

2015) studied that several times traders give themselves credit for serving investors to book their profits and then blame external aspects when suffers loss also referred to as self-attribution bias.

Fisher and Statman (

2000);

Pompian (

2006) on the other hand studied other cognitive biases such as representativeness, ambiguity-aversion, mental accounting, confirmation, hindsight, an illusion of control, and framing biases. Similarly, Kleinübing

GoDoi et al. (

2005) found that emotional biases are categorized as deviances from a predictable financial attitude that can be judged based on emotions.

Pompian (

2006) identified more emotional biases. Likewise, optimism bias

Pompian (

2006), loss aversion bias Kleinübing

GoDoi et al. (

2005), regret aversion bias

Barber and Odean (

2001) were proposed by the respective authors.

Personal attributes are highly influenced while making decisions for investments. Comprehensive studies have taken place to comprehend the association between the type of personality and the investment attitude of an entrepreneur. Scholars have employed distinct traits of personality and have discovered the association between personal style and the ability to tolerate risk. The renowned inventories employed are from the big five model (

Mayfield et al. 2008;

Brown and Taylor 2014;

Bucciol and Zarri 2017;

Akhtar et al. 2018;

Filbeck et al. 2005).

Hence, a discrepancy in the personality type of the investor and the selected portfolio can unfavorably affect an individual’s wealth. Therefore, the financial consultant must understand the psychology of the potential investor before providing their respective investment proposal (

Kannadhasan et al. 2016).

The literature also focuses on financial knowledge or learning that is widely regarded as a life skill leading to economic growth and good fortune.

Kappal and Rastogi (

2020) highlighted that financial awareness or literacy embraces knowledge, expertise, attitude, and personal traits that are essential to make smooth financial-decisions and achieve financial goals. Furthermore, the average financial literacy counts throughout G20 countries are 12.7 out of a maximum of 21 in which Pakistan lacks behind therefore, the point of concern is that financial knowledge should be well equipped in businesses because these skills aid individuals, to choose those financial products that will secure their future. Considerably, parents also influence investment behavior. An optimistic and positive approach of their adults and surroundings will favorably help in gaining worthy financial knowledge (

Grohmann et al. 2015). According to,

Hibbert et al. (

2004), financial wisdom inherited from parents significantly influences the young grown-ups’ financial prudence because families who duly pay their outstanding never misuse their credit-cards this ultimately affects the children that they evade incurring debts.

Bucciol and Veronesi (

2014) stated that parent’s financial socialization illustrates a 16% rise in the chances of saving funds when they mature this leads to a 30% increase in saving in all. Similarly, Akhtar et al. 2018 pointed out that family supervision, social-influence, and media also stimulate the financial decisions of investors. Besides,

Kumar et al. (

2018) address that education influences individuals’ financial behavior towards affairs related to finance. (

Mishra and Metilda 2015) asserted that highly educated people are more anxious about their savings and allocate their funds more vigilantly as compared to those who are not well-qualified because education increases overconfidence and self-efficacy bias. Correspondingly, the authors also assert that experience years in investment activity also influence while selecting the portfolio. Thus, investors who have more working experience possess overconfidence bias in their attitude whereas, less experienced investors have no impact on the self-attribution bias.

Tang and Baker (

2016) addressed that several psychographic factors highly affect the financial decisions of the investors. High self-esteem in an individual will expose better financial behavior. Hence, in light of the above studies, it is clear that both genders exhibit an effective role in the field of investment.

Charness and Gneezy (

2012) mentioned that female investors are risk-averse and they fail to do better future planning for investment. On the contrary,

Hayat (

2016) discussed the importance of financial knowledge asserting no difference in gender regarding attitude. However,

Cramer et al. (

2002) mentioned that female entrepreneurs can absorb risk and occurring challenges at times of unexpected conditions. The current study literature depicts investor psychology and the respective role of gender in investment activity. According to,

Barber and Odean (

2001);

Charness and Gneezy (

2012) female entrepreneur contribute less in investment activity. Scholars have conducted studies in neighboring countries but this exploratory study strives to find the issues that affect the personal decisions regarding investment owning a business in Pakistan. It is worth mentioning that female entrepreneurship is an emergent segment in the population of investors that is not deliberated nor studied comprehensively therefore, this study aims to add the best of knowledge for the researchers globally.

3. Research Design

Prevailing study adopted the inductive approach to comprehend the ground realities and comprehensive responses that help make us aware of the issue. The evolution of entrepreneurship in Pakistan and rapidly increasing female contribution have led to escalating distinct ventures found or co-founded by female citizens in the economy. This study discusses two multi-national cities in Pakistan, Karachi and Lahore, because these cities are considered the incubator accelerator centers such as The Nest I/O & Invest2Innovate, and others provide networks to connect mentoring, coaching and capital to fresh entrepreneurs. Karachi is considered the financial asset for Pakistan that headquarters several multi-national corporations and is a hub for investors.

Lahore is another city selected for the current study, which is home to the educational center and has been initiated as an incubator and accelerator to promote business for women to become competent entrepreneurs. This study adopts a non-probability approach as a purposive and snowball sampling method. For this sampling technique, it is imperative to have homogenous subjects and having similar criteria (

Guest et al. 2006). The condition to conduct an interview is discussed as the interviewee must have three years of running the business; she should be living in Karachi or Lahore and would have invested in two or more different financial instruments such as bonds, saving deposits, mutual funds, stock market, real estate, insurance company or peer to peer lending. The snowball sampling method was applied to get a response from one proficient respondent referring to other similar candidates.

Table 1 presents a brief respondent profile.

Guest et al. (

2006) explained that purposive sampling requires the sample size to be saturated, referring to a point that restrains new information or themes extracted from the set of data. Thus, this study intended to collect data through comprehensive interviews until we attained saturation.

To study the investment behavior of female entrepreneurs, the exploratory interview approach was nominated to execute further research because it is comfortable to use an inductive approach for collecting sensitive data. This enables us to apprehend attitudes and explore intuitive feelings and complicated phenomena.

Kappal and Rastogi (

2020) highlighted that interrogating has an opportunity for an examination that assists the scholar to evolve with every interview. Similarly,

Matlay and Man (

2006) emphasized those entrepreneurs who learn competently, are capable to actively seek learning opportunities. However, such opportunities give a tough time to avail. This is done by observing others and then learn things to avail opportunities out of one’s domain. According to them, semi-structured interviews are the better perception that exhibits the respondent’s biases.

Baig and Khalidi (

2020) pointed out that interview is a suitable instrument for grounded theory, interviewees allow us to understand the ground reality, feelings, accountabilities, and also allows for peeking data insight required for exploration and considering the issues.

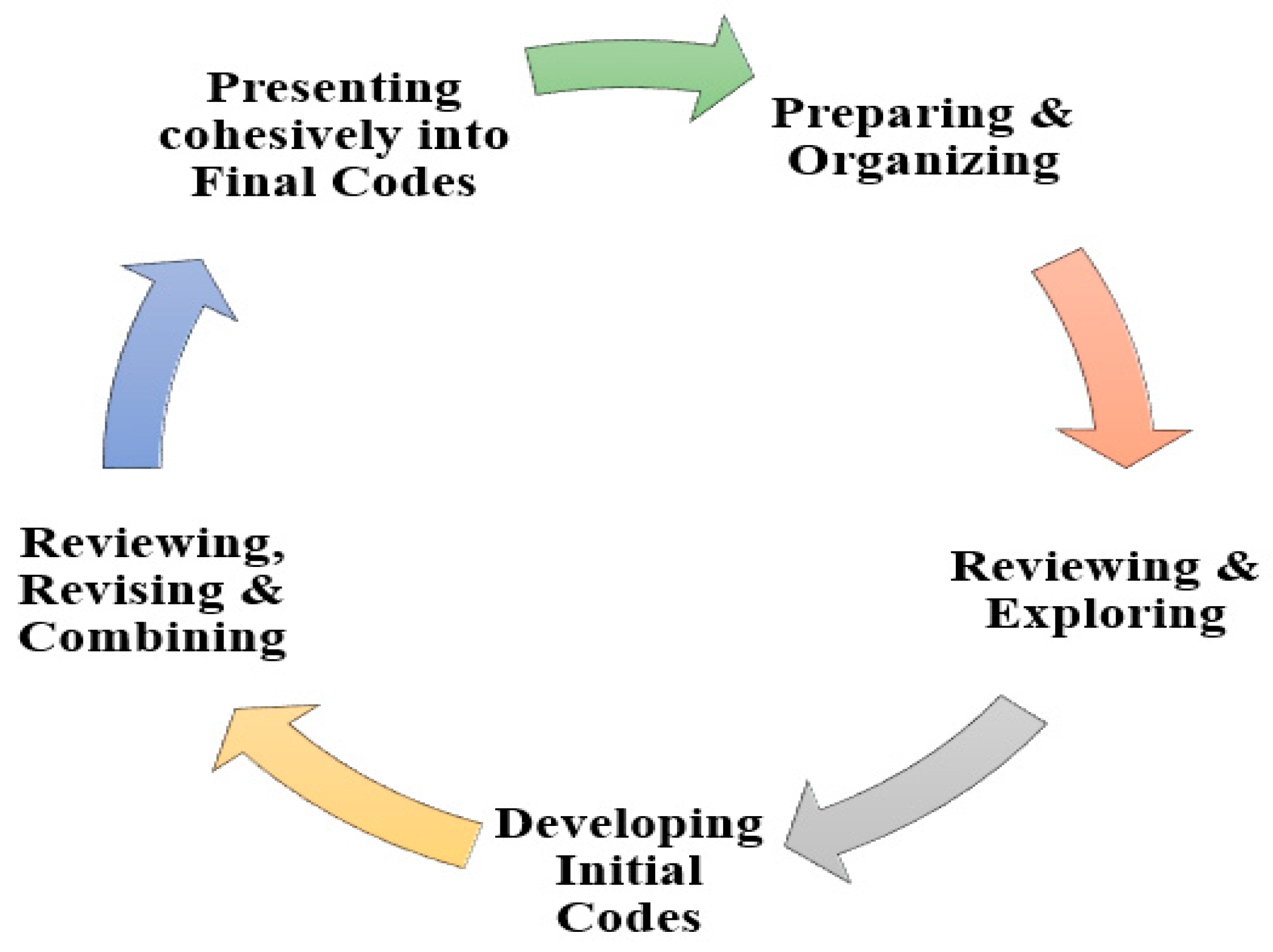

Hence, this study employed a manual coding approach to directly interact with the respondents. Interviews were conducted in congenial environments such as their working place or restaurants and were recorded for the study. The interview took approximately half or one hour. Later the recordings were transcribed. Following

Corbin and Strauss (

1990), the open-ended question technique was used to obtain codes and to better interpret and categorize interviewee viewpoints and perceptions regarding investment instruments. Consequently, this study went through a process of coding as illustrated in

Figure 1.

The responses were recognized as the initial themes, then connections between several codes were cohesively employed to derive the focused categories. As illustrated in

Table 2. To estimate the validity of the coded data, it was proved with the prevailing literature and associated studies. This procedure was recapped after every interview that eventually directed towards the next interview and finally refinement for selective coding.

4. Result and Findings

Initially, it is very hard to absorb the risk that comes across women while establishing her business (

Bowen and Hisrich 1986;

Agarwal and Lenka 2018). On the contrary,

Kappal and Rastogi (

2020) exhibited that risk attitude in investment is not the same. This study assembled and evaluated data based on common subject matter that was finalized when 75% of interviewees communicated about a specific subject. Subsequently, the analyzed data emerged into 13 such themes under six constructs.

4.1. Social Influence

Parents influence in Investment Decision refers to parents influence on their young ones in terms of their habits and beliefs. In all, 83% of the interviewee stated that although, parents never discussed financial issues with them. However, still, they very well know what the importance of money is by observing parent’s attitudes. This observation taught them that money should be earned and saved. Thus, 88% of the responses demonstrated that investment choices are acquired by observing parents. For instance, parents investing in saving accounts so young ones will also follow the same. Similarly, if elders are investing in shares so their children do possess its knowledge and invest in the equity market.

Influence of societal experiences refers to the interrogation process, it was witnessed that friends and society greatly affect the investment decision. Although they want to invest in the equity asset class, the fear of societal experience refrains them because people around them suffered a loss in trading with shares in the stock market. Thus, this made them reluctant to invest in that market. Hence, 72% of people influenced by their friends, family, society, and community experiences depicted bad experiences regarding the stock market. This eventually discouraged them to perform investment activity in shares.

Investment Consultant means that women have limited knowledge of investment tools and instruments. Therefore, 94% of women business owners seek advisors or consultants to assist them in managing their wealth. The investment consultant may be their respective bank, kin, lawyer, or professional chartered accountant. Moreover, they also do some research after seeking valuable counsel from their respective consultant.

4.2. Personal Influence

Financially Independent refers to women interviewees that are mostly running their businesses. Who are ambitious and want to accomplish their goals because ambition reveals healthy self-esteem if well-aimed and backed by values. This makes them self-confident and enables them to make a difference in their surroundings keeping things under control.

Figure 2 illustrates that 83%of women invest for the sake of their families.

A total of 88% of interviewees stated that financial independence makes us aware of the nuts and bolts while performing the investing activity. More than 77% preferred that they are against interference and want their sole decisions for their surplus money to be invested.

4.3. Behavioral Influence

Risk aversion refers to those women working in the field, who demonstrate confidence when it comes to their business. Sometimes they take the risk, and sometimes they are afraid to take risks while investing. However, 83% of the interviewees stated that they are afraid when it comes to their investing activity. The majority of their portfolio consists of fixed deposits, mutual funds, and government provident funds. This study observed that risk-averse attitude generates because of lack of sound knowledge about the market this showed that in Karachi and Lahore, women are not good players in the stock market and do not want to expose themselves.

Optimism means to exhibit positive approach. Women running business in Pakistan demonstrated positive results of optimism such as they are action-orientation, persistent, committed, and capable of motivating or stimulate others because they are found adaptable and have shown survival in unexpected conditions like Pakistan. Thus, 77% of women demonstrated optimism in their investment behavior.

Mental Accounting refers to a concept where one plans, evaluate, and organize its wealth to fulfill goals in life. Maintaining different accounts for revenues and expenditures while refraining from overspending. Thus, we found that 88% of female entrepreneurs keep organized records to overcome liquidity issues.

4.4. Investment Attitude

Long-term Investment Attitude explains that working women are good at contingent planning with anticipation to save more than recurring expenditures. On the contrary, there are a few who have not suffered or confronted hardships of life and are fond of spending rather than saving. In all, practically, there are 77% of women who invest for a long period ensuring that those investments are not withdrawn very often.

Conservative Investment Attitude explains that working women are mostly conservative because they absorb low risk simultaneously, safeguard their invested principal. Thus, 88% of the respondents invest in volatile instruments.

4.5. Controlling Factors

Uncertainty displays that about 94% of the interviewee delve into new investments as they think optimistically. Different asset classes require comprehensive-time to liberate oneself but unfortunately, due to scarce time riskier investment is not preferred. On contrary, they have guts to survive in uncertainty and maintain sustainability.

Financial Literacy refers to sound knowledge about financial activities which is unfortunately limited because in Pakistan few women are running their own business having little knowledge about investment tools moreover, they have little exposure in riskier asset classes and are willing to expand their portfolio by investing in equity or other capital investments.

4.6. Investment Decision

Alternative Investment refers to those women executing businesses who really understand that they possess limited knowledge about instruments. Scarce time refrain them in increasing their knowledge regarding certain assets. However, all of them have the curiosity to gain more knowledge about certain assets in which they need to learn more and increase their portfolio. The potential interviewees had made their perceptions about different investment avenues and they drove their investment decisions according to these perceptions.

Figure 3 illustrates that 88% of women viewed fixed deposits as a secured and profitable tool to invest. A total of 77% felt real estate as a sound and sustainable investment. Similarly, 77% of females agreed that investing in mutual funds is better on contrary, since their lack of knowledge about other asset classes prevented them from paying lump sum investments.

However, they followed an organized investment plan to venture into mutual funds for regular investments. A sum of, 83% considered gold as the best option if needed for abstract investment. Only 16% were found who play in stocks.

Retirement Plan displayed that a total of 88% of respondents have not planned for retirement. They knew it very well that it requires few concrete decisions before their retirement.

5. Discussion

These respondents showed risk-averse behavior towards investments as a result of, limited knowledge and scarce time to understand various investment areas. Female entrepreneurs preferred to allocate their funds in bank saving A/c and mutual funds. They wished to diversify their area by allocating their funds in other asset classes after having sound knowledge and skill regarding it. This depicted that are willing to engross risk after studying different investment tools. According to

Prasad et al. (

2014), in India, women who own businesses prefer capital appreciation, security, liquidity, speculation, tax-benefits, and stable income. However, the findings of their study depicted that they are not provoked to liquid assets, speculation, and stable income. However, they asserted that women are risk-averse and select uncomplicated and convenient tools to invest. On contrary, this study found that women invest in their families.

Sahi et al. (

2013) inquired about investment behavior along with its biases. The scholars conducted in-depth interviews and found that investors are risk-averse. They evaluate risk and then invest. Moreover, society also influences their attitude toward investment activity. The current study illustrates that the majority of female entrepreneurs are not confident enough to make decisions on their own. Even though they refer to financial consultants, they take final decisions after verifying it through other means. Moreover, they feel that they should make more efforts to literate themselves financially as they stay away from risky assets. In short, they would take a risk but they are risk-averse. They need training for these risky asset classes.

Paluri and Mehra (

2016) studied the women’s financial behavior and categorized them into clusters base on financial attitude. They took a sample of 177 women, 132 were between 18–35 years, 76 were students and 16 were self-employed.

The prevailing study classifies women according to their financial behavior and declared that such sorting would help organizations to trade appropriate products to diverse clusters. This study proposes to consider female entrepreneurs as a separate segment of the market. According to,

Paluri and Mehra (

2016), women tend to be economical and require immediate satisfaction after spending their funds. This has not proved good in the case of Pakistani female entrepreneurs. Current research depicts that women are good planners moreover, they save for their enterprise and families. Similarly,

Rashid and Ratten (

2020) explored the entrepreneurial experience of 12 artisans by conducting qualitative research with semi-structured interviews in Pakistan. The scholars found that to survive in the market, it is necessary to be adaptable. They further revealed that women heavily rely on rational learning by having a strong relationship with their subordinates and work. This ultimately results in a successful, profitable business and an optimistic approach towards investment and executing entrepreneurship.

Since female entrepreneurs have limited knowledge, and their perception regarding risk is uncertain, they firmly believe that mutual funds are better for investing and tax saving. Moreover, fixed deposits are a safe option for bulky investments. Whereas, 77% of the interviewee prefer investing in real estate as they perceive it as a secured investment. About 83% of respondents prefer gold as another good option.

Parents also influence their attitude toward investment. According to

Webley and Nyhus (

2006) and

Grohmann et al. (

2015), family plays a crucial role in educating financial literacy. Moreover, children copy the investing and savings behavior of their adults. For Pakistan women, entrepreneurs engage in investment instruments for their families. They agree that if parents have a risk-taking attitude, they also venture into such assets as equity.

Practically, they accept the fact that discussing financial matters with young ones make them live in the real world and also prepare them for future rational decisions. On the contrary, negative experiences influence those who have lost money in the stock market. They seek an investment consultant who counsels them and finally after comprehensive research work they make decisions. This ultimately augments its portfolio. At the same time, lack of consultancy heads towards traditional investments.

This study also reveals that female entrepreneurs engage in long-term investment having a risk-averse attitude. Although they take the risk in their business, they avoid risk in their investments. They efficiently plan for their surplus when they budget their expenditures. If they find any investment in loss, they wait till it becomes profitable. They try to liquidate investments in losses. They analyze their portfolio but do not study investments in detail. The study discusses behavioral biases that affect their selection of instruments such as risk aversion and mental accounting, simultaneously keeping an optimistic view. It was found that they have not sufficiently equipped themselves for retirement. Similarly, a lack of financial literacy, the time they fail to be diversified.

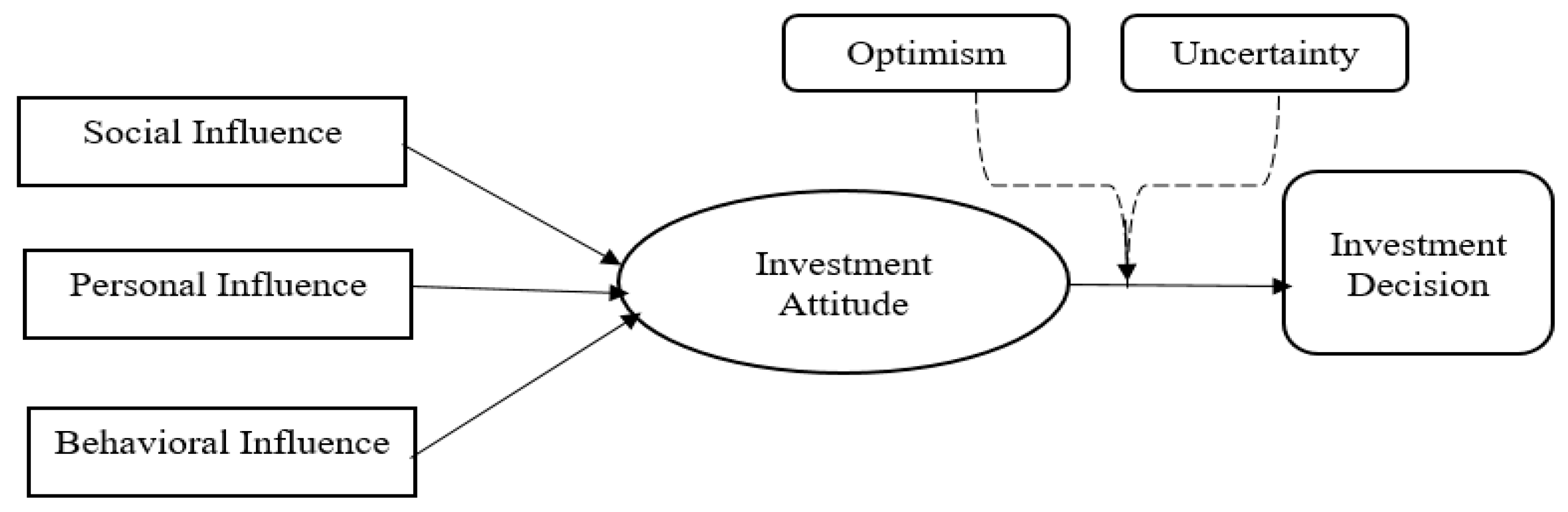

Figure 4 is proposed to be tested empirically for its robustness.

The factors that affect investment behavior is limited knowledge and uncertain conditions that heads to financial satisfaction and plan for retirement. This research splits female entrepreneurs into four wide categories of factors that highly impact their behavior such as limited knowledge of instruments and uncertainty playing the moderating role which leads to healthier investment. The study gives an insight into female entrepreneurs and their investment behavior in two big cosmopolitan cities of Pakistan that require empirical testing on a larger sample size in several other cities to crosscheck the robustness of the proposed model that will ultimately provide guiding principle to policy-makers and financial consultants to give training to female entrepreneurs in our society.

6. Conclusions

This study concludes by revealing the personal decisions taken by female entrepreneurs in Karachi and Lahore. Moreover, it aims to exhibit a growing segment of investment. This study identified that female entrepreneurs invest in long-term funds having conservative attitudes, and therefore, seek financial consultants. They are greatly affected by society and parents on the contrary, and want to be independent in their decisions. Limited knowledge due to time constraints has prevented them from the riskier investment but they still believe in adaptability in uncertainty, keeping an optimistic attitude towards their investments. Thus, appropriate knowledge of financial products and ample time to think over will make them learn better and will also play a tremendous role in distinct markets in the emerging economy like Pakistan.

This study exposes female entrepreneur’s behavioral biases such as risk aversion and mental accounting. Therefore, scholars can include more biases in their studies that greatly impact their decisions towards investment. This study proposes 18 female entrepreneur interviews in the big cities Karachi and Lahore of Pakistan. It is recommended to conduct a study on a large sample size to extend the understanding of the current research because female entrepreneurs in rural area will depict opposite perceptions regarding investment behavior. Since, Karachi and Lahore are home to multi-cultural, multi-traditional, multi-lingual, and perception migrants so studies can be done on the effect of culture on female entrepreneur behavior concerning investing activity and the young ones who impersonate their parent’s behavior when seeking for financial aid. Hence, for universal exposure, there is a need to investigate the female entrepreneur’s behavior internationally in South Asian countries to further investigate the strong bonding of this relation by examining deeply among the regions.