Perceived Autonomy Support from Peers, Parents, and Physical Education Teachers as Predictors of Physical Activity and Health-Related Quality of Life among Adolescents—A One-Year Longitudinal Study

Abstract

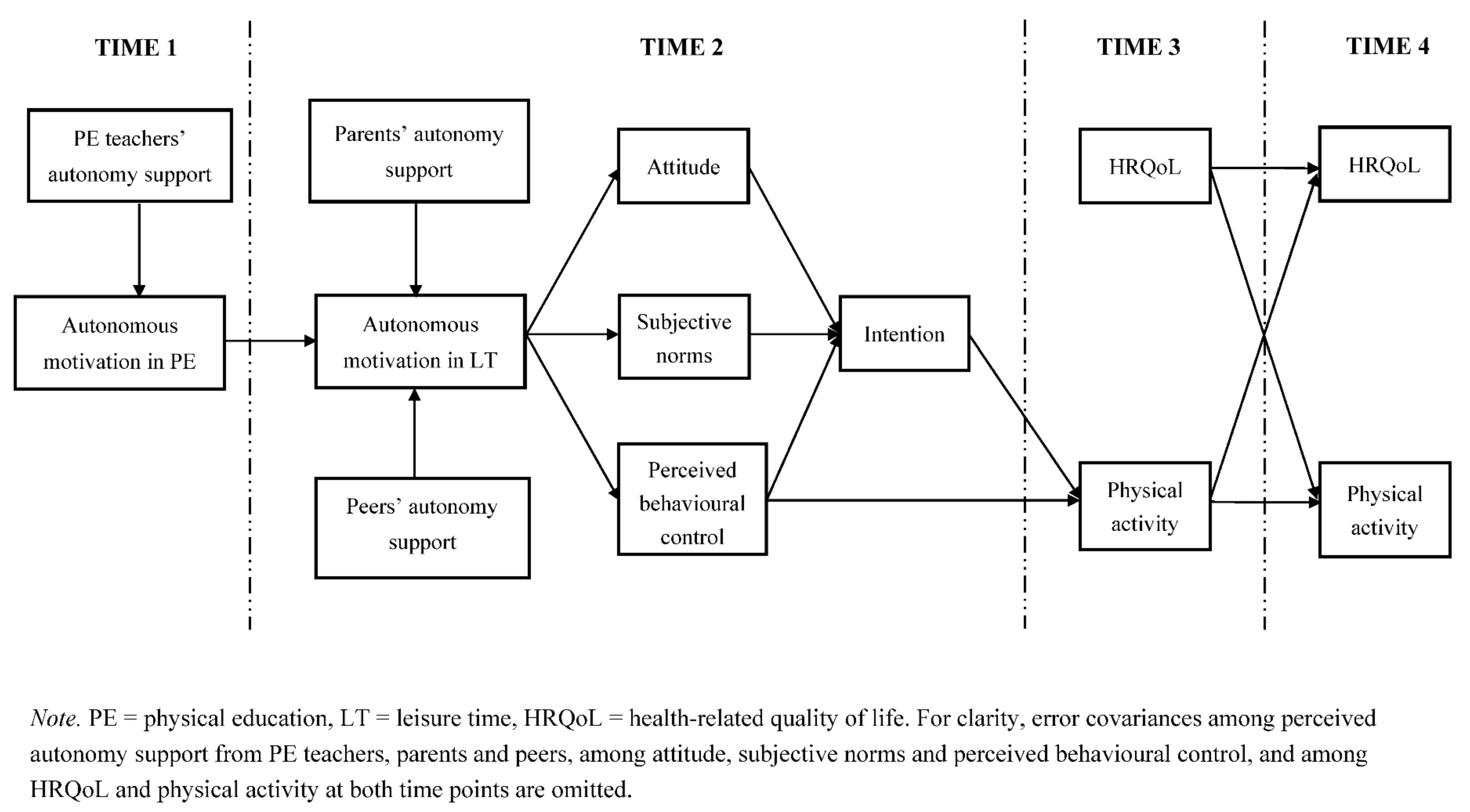

:1. The Present Study

2. Method

Participants and Procedure

3. Measures

3.1. Perceived Autonomy Support from Peers, Parents and PE Teachers

3.2. Autonomous Motivation towards PE

3.3. Autonomous Motivation towards during Leisure Time

3.4. Attitude, Subjective Norms, Perceived Behavioural Control, and Intentions

3.5. Self-Reported Physical Activity

3.6. HRQoL

4. Data Analysis

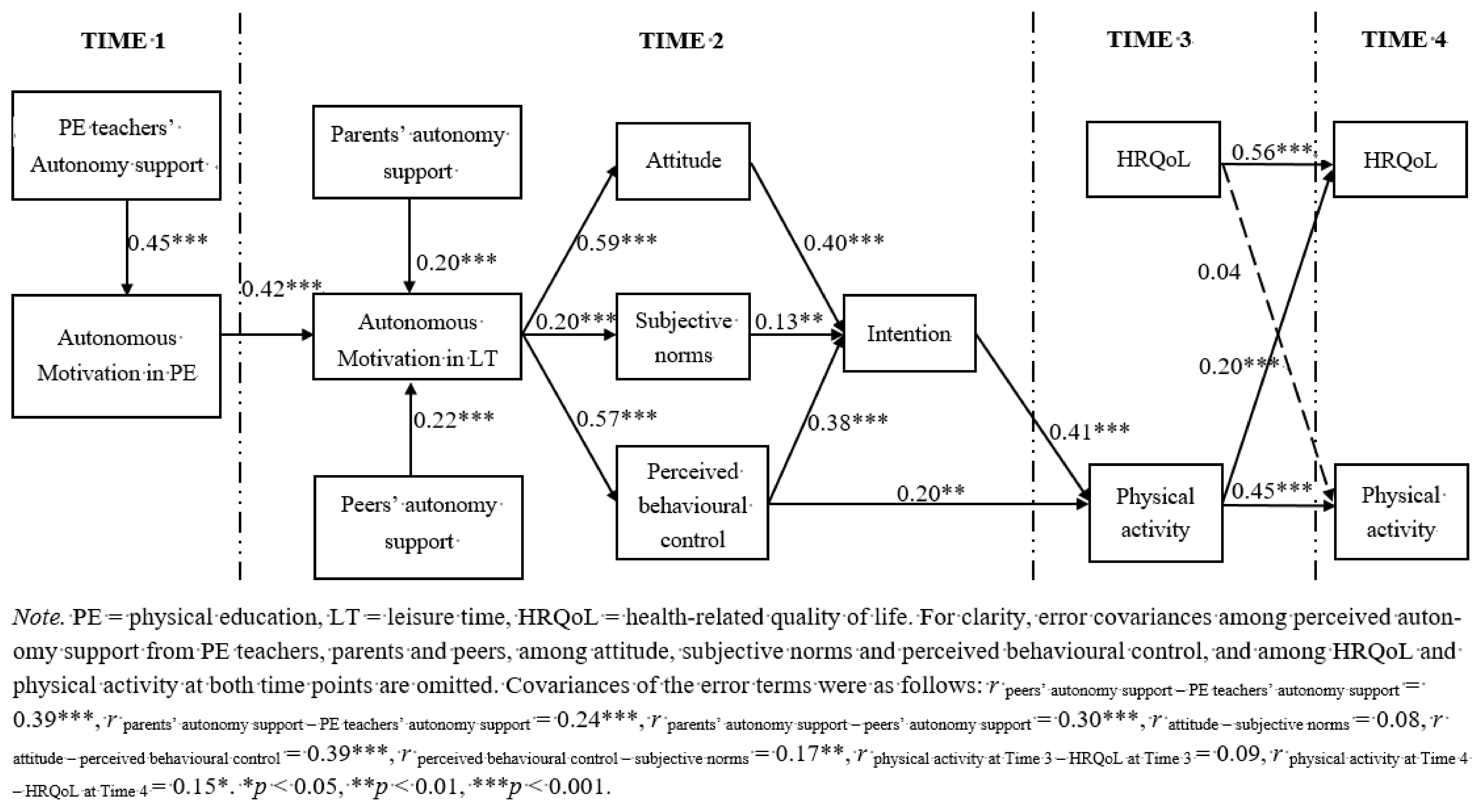

5. Results

5.1. Preliminary Analysis

5.2. Main Analysis

6. Discussion

Strengths, Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shumaker, S.A.; Naughton, M.J. The international assessment of health-related quality of life: A theoretical perspective. In The International Assessment of Health-Related Quality of Life: Theory, Translation, Measurement and Analysis; Shumaker, S.A., Berzon, R.A., Eds.; Rapid Communication: Oxford, UK, 1995; pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Meade, T.; Dowswell, E. Adolescents’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL) changes over time: A three year longitudinal study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2016, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Poitras, V.J.; Gray, C.E.; Borghese, M.M.; Carson, V.; Chaput, J.-P.; Janssen, I.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Pate, R.R.; Connor Gorber, S.; Kho, M.E.; et al. Systematic review of the relationships between objectively measured physical activity and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. Physiol. Appl. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41 (Suppl. 3), S197–S239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisegger, C.; Cloetta, B.; von Rueden, U.; Abel, T.; Ravens-Sieberer, U.; European Kidscreen Group. Health-related quality of life: Gender differences in childhood and adolescence. Soz. Prav. 2005, 50, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: A pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1·6 million participants. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrovouniotis, F. Inactivity in Childhood and Adolescence: A Modern Lifestyle Associated with Adverse Health Consequences. Sport Sci. Rev. 2012, 21, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J.; Cheon, S.H. Autonomy-supportive teaching: Its malleability, benefits, and potential to improve educational practice. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 56, 54–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.J.; Marques, M.M.; Silva, M.N.; Brunet, J.; Duda, J.; Haerens, L.; La Guardia, J.; Lindwall, M.; Londsdale, C.; Markland, D.; et al. Classification of techniques used in self-determination theorybased interventions in health contexts: An expert consensus study. Motiv. Sci. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.D. The Trans-Contextual Model of Autonomous Motivation in Education: Conceptual and Empirical Issues and Meta-Analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2016, 86, 360–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J.; Ratelle, C.F. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: A hierarchical model. In Handbook of Self-Determination Research; Deci, E.L., Ryan, R.M., Eds.; University of Rochester Press: Rochester, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 37–63. [Google Scholar]

- González-Cutre, D.; Sicilia, Á.; Beas-Jiménez, M.; Hagger, M.S. Broadening the trans-contextual model of motivation: A study with Spanish adolescents. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2014, 24, e306–e319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.D.; Hein, V.; Soos, I.; Karsai, I.; Lintunen, T.; Leemans, S. Teacher, peer and parent autonomy support in physical education and leisure time physical activity: A trans-contextual model of motivation in four nations. Psychol. Health 2009, 24, 689–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronikowski, M.; Bronikowska, M.; Maciaszek, J.; Glapa, A. Maybe it is not a goal that matters: A report from a physical activity intervention in youth. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2018, 58, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Hardcastle, S.J.; Chater, A.; Mallett, C.; Pal, S.; Chatzisarantis, N. Autonomous and controlled motivational regulations for multiple health-related behaviors: Between-and within-participants analyses. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2014, 2, 565–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, D.K.C.; Zhang, L.; Lee, A.S.Y.; Hagger, M.S. Reciprocal relations between autonomous motivation from self-determination theory and social cognition constructs from the theory of planned behavior: A cross-lagged panel design in sport injury prevention. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2020, 48, 101660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudsepp, L.; Viira, R.; Hannus, A. Prediction of Physical Activity Intention and Behavior in a Longitudinal Sample of Adolescent Girls. Percept. Mot. Skills 2010, 110, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.E.; Macdonald, H.M.; McKay, H.A. Predicting physical activity intention and behaviour among children in a longitudinal sample. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 62, 3146–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, S.A.; Matthews, C.E.; Ebbeling, C.B.; Moore, C.G.; Cunningham, J.E.; Fulton, J.; Hebert, J.R. The effect of social desirability and social approval on self-reports of physical activity. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2005, 161, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalajas-Tilga, H.; Hein, V.; Koka, A.; Tilga, H.; Raudsepp, L.; Hagger, M.S. Application of the trans-contextual model to predict change in leisure time physical activity. Psychol. Health 2021, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polet, J.; Lintunen, T.; Schneider, J.; Hagger, M.S. Predicting change in middle school students’ leisure-time physical activity participation: A prospective test of the trans-contextual model. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 50, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standage, M.; Gillison, F. Students’ motivational responses toward school physical education and their relationship to general self-esteem and health-related quality of life. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2007, 8, 704–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standage, M.; Gillison, F.B.; Ntoumanis, N.; Treasure, D.C. Predicting students’ physical activity and health-related well-being: A prospective cross-domain investigation of motivation across school physical education and exercise settings. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2012, 34, 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koka, A. The relative roles of teachers and peers on students’ motivation in physical education and its relationship to self-esteem and Health-Related Quality of Life. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 2014, 45, 187–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Sun, H.; Dai, J. Peer Support and Adolescents’ Physical Activity: The Mediating Roles of Self-Efficacy and Enjoyment. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2017, 42, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anokye, N.K.; Trueman, P.; Green, C.; Pavey, T.G.; Taylor, R.S. Physical activity and health related quality of life. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wunsch, K.; Nigg, C.R.; Weyland, S.; Jekauc, D.; Niessner, C.; Burchartz, A.; Schmidt, S.; Meyrose, A.-K.; Manz, K.; Baumgarten, F.; et al. The relationship of self-reported and device-based measures of physical activity and health-related quality of life in adolescents. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.D.; Hein, V.; Pihu, M.; Soós, I.; Karsai, I. The perceived autonomy support scale for exercise settings (PASSES): Development, validity, and cross-cultural invariance in young people. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2007, 8, 632–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudas, M.; Biddle, S.; Fox, K. Perceived locus of causality, goal orientations, and perceived competence in school physical education classes. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 1994, 64, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalajas-Tilga, H.; Koka, A.; Hein, V.; Tilga, H.; Raudsepp, L. Motivational processes in physical education and objectively measured physical activity among adolescents. J. Sport Health Sci. 2020, 9, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koka, A.; Tilga, H.; Kalajas-Tilga, H.; Hein, V.; Raudsepp, L. Perceived Controlling Behaviors of Physical Education Teachers and Objectively Measured Leisure-Time Physical Activity in Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ryan, R.M.; Connell, J.P. Perceived locus of causality and internalization: Examining reasons for acting in two domains. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Constructing a TPB Questionnaire: Conceptual and Methodological Considerations. 2003. Available online: http://people.umass.edu/aizen/pdf/tpb.measurement.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2018).

- Pihu, M.; Hein, V.; Koka, A.; Hagger, M.S. How students’ perceptions of teachers’ autonomy-supportive behaviours affect physical activity behaviour: An application of the trans-contextual model. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2008, 8, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koka, A.; Tilga, H.; Kalajas-Tilga, H.; Hein, V.; Raudsepp, L. Detrimental Effect of Perceived Controlling Behavior from Physical Education Teachers on Students’ Leisure-Time Physical Activity Intentions and Behavior: An Application of the Trans-Contextual Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godin, G.; Shephard, R.J. A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Can. J. Appl. Sport Sci. 1985, 10, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hein, V.; Koka, A.; Kalajas-Tilga, H.; Tilga, H.; Raudsepp, L. The effect of grit on leisure time physical activity. An Application of Theory of Planned Behaviour. Balt. J. Health Phys. Act. 2020, 12, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, V.; Koka, A.; Tilga, H.; Kalajas-Tilga, H.; Raudsepp, L. The Roles of Grit and Motivation in Predicting Children’s Leisure-time Physical Activity: One-year Effects. Percept. Mot. Skills 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilga, H.; Kalajas-Tilga, H.; Hein, V.; Raudsepp, L.; Koka, A. How does perceived autonomy-supportive and controlling behaviour in physical education relate to adolescents’ leisure-time physical activity participation? Kinesiology 2020, 52, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viira, R.; Koka, A. Health-related quality of life of Estonian adolescents: Reliability and validity of the PedsQLTM 4.0 Generic Core Scales in Estonia. Acta Paediatr. 2011, 100, 1043–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varni, J.W.; Seid, M.; Kurtin, P.S. PedsQL 4.0: Reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Med. Care 2001, 39, 800–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilga, H.; Hein, V.; Koka, A.; Hagger, M.S. How Physical Education Teachers’ Interpersonal Behaviour is Related to Students’ Health-Related Quality of Life. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 64, 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pihu, M.; Hein, V. Autonomy support from physical education teachers, peers and parents among school students: Trans-contextual motivation model. Acta Kinesiol. Univ. Tartu. 2007, 12, 116–128. [Google Scholar]

- Bronikowski, M.; Bronikowska, M.; Laudańska-Krzemińska, I.; Kantanista, A.; Morina, B.; Vehapi, S. PE Teacher and Classmate Support in Level of Physical Activity: The Role of Sex and BMI Status in Adolescents from Kosovo. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 290349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farooq, A.; Martin, A.; Janssen, X.; Wilson, M.G.; Gibson, A.-M.; Hughes, A.; Reilly, J.J. Longitudinal changes in moderate-to-vigorous-intensity physical activity in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e12953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheon, S.H.; Reeve, J.; Ntoumanis, N. A needs-supportive intervention to help PE teachers enhance students’ prosocial behavior and diminish antisocial behavior. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2018, 35, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sevil-Serrano, J.; Aibar, A.; Abós, Á.; Generelo, E.; García-González, L. Improving motivation for physical activity and physical education through a school-based intervention. J. Exp. Educ. 2020, 88, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilga, H.; Hein, V.; Koka, A. Effects of a Web-Based Intervention for PE Teachers on Students’ Perceptions of Teacher Behaviors, Psychological Needs, and Intrinsic Motivation. Percept. Mot. Skills 2019, 126, 559–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilga, H.; Kalajas-Tilga, H.; Hein, V.; Raudsepp, L.; Koka, A. 15-Month Follow-Up Data on the Web-Based Autonomy-Supportive Intervention Program for PE Teachers. Percept. Mot. Skills 2020, 127, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheon, S.H.; Reeve, J.; Yu, T.H.; Jang, H.R. The teacher benefits from giving autonomy support during physical education instruction. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2014, 36, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilga, H.; Kalajas-Tilga, H.; Hein, V.; Raudsepp, L.; Koka, A. Effects of a Web-Based Autonomy-Supportive Intervention on Physical Education Teacher Outcomes. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgueño, R.; Abós, Á.; García-González, L.; Tilga, H.; Sevil-Serrano, J. Evaluating the Psychometric Properties of a Scale to Measure Perceived External and Internal Faces of Controlling Teaching among Students in Physical Education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilga, H.; Hein, V.; Koka, A.; Hamilton, K.; Hagger, M.S. The role of teachers’ controlling behaviour in physical education on adolescents’ health-related quality of life: Test of a conditional process model. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 39, 862–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilga, H.; Hein, V.; Koka, A. Measuring the perception of the teachers’ autonomy-supportive behavior in physical education: Development and initial validation of a multi-dimensional instrument. Meas. Phys. Educ. Exerc. Sci. 2017, 21, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koka, A.; Tilga, H.; Hein, V.; Kalajas-Tilga, H.; Raudsepp, L. A multidimensional approach to perceived teachers’ autonomy support and its relationship with intrinsic motivation of students in physical education. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Montero-Carretero, C.; Barbado, D.; Cervelló, E. Predicting Bullying through Motivation and Teaching Styles in Physical Education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zimmermann, J.; Tilga, H.; Bachner, J.; Demetriou, Y. The German Multi-Dimensional Perceived Autonomy Support Scale for Physical Education: Adaption and Validation in a Sample of Lower Track Secondary School Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, J.; Tilga, H.; Bachner, J.; Demetriou, Y. The Effect of Teacher Autonomy Support on Leisure-Time Physical Activity via Cognitive Appraisals and Achievement Emotions: A Mediation Analysis Based on the Control-Value Theory. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Correlations | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

| 1. Peers’ autonomy support (T2) | |||||||||||||

| 2. Parents’ autonomy support (T2) | 0.30 ** | ||||||||||||

| 3. PE teachers’ autonomy support (T1) | 0.40 ** | 0.24 ** | |||||||||||

| 4. Autonomous motivation in PE (T1) | 0.25 *** | 0.20 ** | 0.45 *** | ||||||||||

| 5. Autonomous motivation in LT (T2) | 0.38 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.51 ** | |||||||||

| 6. Attitude (T2) | 0.26 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.14 * | 0.36 *** | 0.60 *** | ||||||||

| 7. Subjective norms (T2) | 0.19 ** | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.20 ** | 0.18 * | |||||||

| 8. Perceived behavioural control (T2) | 0.26 *** | 0.31 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.33 *** | 0.57 *** | 0.60 *** | 0.25 *** | ||||||

| 9. Intention (T2) | 0.36 *** | 0.31 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.30 *** | 0.63 *** | 0.66 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.66 *** | |||||

| 10. Physical activity (T3) | 0.28 *** | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.14 * | 0.39 *** | 0.37 *** | 0.24 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.56 *** | ||||

| 11. HRQoL (T3) | 0.18 * | 0.21 ** | 0.23 *** | 0.21 ** | 0.25 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.04 | 0.26 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.21 ** | |||

| 12. Physical activity (T4) | 0.19 ** | 0.11 * | 0.07 | 0.15 * | 0.27 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.11 | 0.22 *** | 0.36 *** | 0.46 *** | 0.13 * | ||

| 13. HRQoL (T4) | 0.17 * | 0.22 ** | 0.12 | 0.15 ** | 0.28 *** | 0.27 *** | 0.12 * | 0.29 *** | 0.33 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.59 *** | 0.27 *** | |

| M | 4.95 | 5.98 | 5.25 | 5.67 | 5.86 | 6.09 | 4.23 | 5.59 | 5.70 | 4.35 | 1.05 | 4.38 | 1.23 |

| SD | 1.41 | 1.08 | 1.20 | 1.24 | 1.14 | 1.02 | 1.47 | 1.18 | 1.28 | 1.10 | 0.55 | 1.05 | 0.61 |

| α | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.80 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.67 | 0.81 | 0.93 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.93 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tilga, H.; Kalajas-Tilga, H.; Hein, V.; Raudsepp, L.; Koka, A. Perceived Autonomy Support from Peers, Parents, and Physical Education Teachers as Predictors of Physical Activity and Health-Related Quality of Life among Adolescents—A One-Year Longitudinal Study. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 457. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/educsci11090457

Tilga H, Kalajas-Tilga H, Hein V, Raudsepp L, Koka A. Perceived Autonomy Support from Peers, Parents, and Physical Education Teachers as Predictors of Physical Activity and Health-Related Quality of Life among Adolescents—A One-Year Longitudinal Study. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(9):457. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/educsci11090457

Chicago/Turabian StyleTilga, Henri, Hanna Kalajas-Tilga, Vello Hein, Lennart Raudsepp, and Andre Koka. 2021. "Perceived Autonomy Support from Peers, Parents, and Physical Education Teachers as Predictors of Physical Activity and Health-Related Quality of Life among Adolescents—A One-Year Longitudinal Study" Education Sciences 11, no. 9: 457. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/educsci11090457