Attachment and the Development of Moral Emotions in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Empathy, Sympathy and Pro-Social Behavior

1.2. Guilt and Reparative Behavior in Relationships

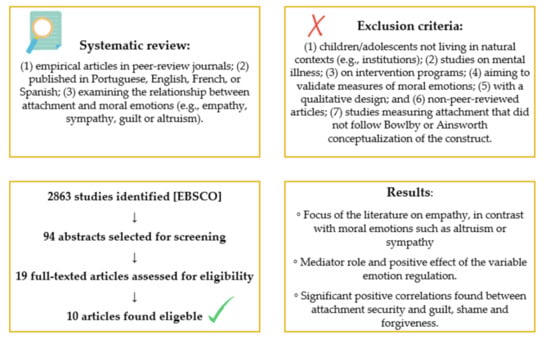

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Article Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Study Selection Procedures

2.3. Data Extraction Procedures

3. Results

3.1. General Description of the Studies: Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives

3.2. General Characteristics of the Sample and Assessments

3.3. Findings on the Different Influences between Attachment and Moral Emotions

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Diamond, L. M., Fagundes, C. P., & Butterworth, M. R. (2012). Attachment style, vagal tone, and empathy during mother–adolescent interactions. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22(1), 165–184. Retrieved from https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00762.x

- Kim, S., & Kochanska, G. (2017). Relational antecedents and social implications of the emotion of empathy: evidence from three studies. Emotion, 17(6), 981–992, Retrieved from http://0-dx-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.1037/emo0000297

- Laible, D. (2007). Attachment with parents and peers in late adolescence: Links with emotional competence and social behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 1185–1197. Retrieved from http://0-dx-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.1016/j.paid.2007.03.010

- Muris, P., Meesters, C., Cima, M., Verhagen, M., Brochard, N., Sanders, A., Kempener, C. Beurskens, J., & Meesters, V. (2014). Bound to feel bad about oneself: relations between attachment and the self-conscious emotions of guilt and shame in children and adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23, 1278–1288. Retrieved from https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.1007/s10826-013-9817-z

- Murphy, P., Laible, D.J., Augustine, M., & Robeson, L. (2015). Attachment’s links with adolescents’ social emotions: The roles of negative emotionality and emotion regulation. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 176(5), 315–329. ISSN: 0022-1325 print / 1940-0896 online. Retrieved from: https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.1080/00221325.2015.1072082

- Paez, A., & Rovella, A. (2019). Vínculo de apego, estilos parentales y empatía en adolescentes. Interdisciplinaria, 36(2), 23-38. Retrieved from: https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.16888/interd.2019.36.2.2

- Panfile, T., & Laible, D. (2012). Attachment security and child’s empathy: the mediating role of emotion regulation. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 58(1), 1-21. Retrieved 16 June 2021, from http://0-www-jstor-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/stable/23098060

- Ştefan, C.A, & Avram, J. (2018). The multifaceted role of attachment during preschool: moderator of its indirect effect on empathy through emotion regulation, Early Child Development and Care, 188(1), 62-76. Retrieved from https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.1080/03004430.2016.1246447

- Stern, J., Costello, M., Kansky, J., Fowler, C., Loeb, E.M, & Allen, J.P. (2021). Here for You: Attachment and the growth of empathic support for friends in adolescence. Child Development, 0(0), 1-16. ISSN: 0009-3920 Online ISSN: 1467-8624. Retrieved from: https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.1111/cdev.13630

- van der Mark, I., van IJzendoorn, M., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J. (2002). Development of empathy in girls during the second year of life: associations with parenting, attachment, and temperament. Retrieved from https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.1111/1467-9507.00210

References

- Ainsworth, M.; Blehar, M.C.; Waters, E.; Wall, S. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation; Lawrence Erlbaum: Oxford, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss, Vol. 3: Loss, Sadness and Depression; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, J. Emotion regulation: Influences of attachment relationships. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 1994, 59, 228–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, M. Introduction to the special section on attachment and psychopathology: 2. Overview of the field of attachment. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1996, 64, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kestenbaum, R.; Farber, E.A.; Sroufe, A.L. Individual differences in empathy among preschoolers: Relation to attachment history. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 1989, 44, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panfile, T.; Laible, D. Attachment security and child’s empathy: The mediating role of emotion regulation. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2012, 58, 1–21. Available online: http://0-www-jstor-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/stable/23098060 (accessed on 16 June 2021). [CrossRef]

- Roque, L.; Verissimo, M.; Fernandes, M.; Rebelo, A. Emotion regulation and attachment: Relationships with children’s secure base during different situational and social contexts in naturalistic settings. Infant Behav. Dev. 2013, 36, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cozolino, L. The Neuroscience of Human Relationships: Attachment and the Developing Social Brain; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ongley, S.F.; Malti, T. The role of moral emotions in the development of children’s sharing behavior. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 50, 1148–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muris, P.; Meesters, C.; Cima, M.; Verhagen, M.; Brochard, N.; Sanders, A.; Kempener, C.; Beurskens, J.; Meesters, V. Bound to feel bad about oneself: Relations between attachment and the self-conscious emotions of guilt and shame in children and adolescents. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2014, 23, 1278–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beffara, B.; Bret, A.G.; Vermeulen, N.; Mermillod, M. Resting high frequency heart rate variability selectively predicts cooperative behaviour. Physiol. Behav. 2016, 164, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, L.M.; Fagundes, C.P.; Butterworth, M.R. Attachment style, vagal tone, and empathy during mother–adolescent interactions. J. Res. Adolesc. 2012, 22, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Mark, I.L.; van IJzendoorn, M.H.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J. Development of empathy in girls during the second year of life: Associations with parenting, attachment, and temperament. Soc. Dev. 2002, 11, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paez, A.; Rovella, A. Vínculo de apego, estilos parentales y empatía en adolescentes. Interdisciplinaria 2019, 36, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Padilla-Walker, L.M.; Christensen, K.J. Empathy and Self-Regulation as Mediators between Parenting and Adolescents’ Prosocial Behavior Toward Strangers, Friends, and Family. J. Res. Adolesc. 2010, 21, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.X.; Spinrad, T.L.; Carter, D.B. Parental emotion regulation and preschoolers’ prosocial behavior: The mediating roles of parental warmth and inductive discipline. J. Genet. Psychol. 2018, 179, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Stillwell, A.M.; Heatherton, T.F. Interpersonal aspects of guilt: Evidence from narrative studies. In Self-Conscious Emotions: Shame, Guilt, Embarrassment, and Pride; Tangney, J.P., Fischer, K.W., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 255–273. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, M.L. The origins of empathic morality in toddlerhood. In Socioemotional Development in the Toddler Years: Transitions and Transformations; Brownell, C.A., Kopp, C.B., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 132–145. [Google Scholar]

- Zahn-Waxler, C.; Radke-Yarrow, M.; Wagner, E.; Chapman, M. Development of concern for others. Dev. Psychol. 1992, 28, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J.; Stuewig, J.; Mashek, D. Moral Emotions and Moral Behavior. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 345–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eisenberg, N. Empathy and sympathy. In Handbook of Emotions, 4th ed.; Lewis, M., Haviland-Jones, J.M., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 677–691. ISBN 9781462536368. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, N.; Shea, C.L.; Carlo, G.; Knight, G. Empathy-related responding and cognition: A “chicken and the egg” dilemma. In Handbook of Moral Behavior and Development Volume 2: Research; Kurtines, W.M., Gewirtz, J., Lamb, J.L., Eds.; Routledge (Psychology Press Ltd.): London, UK, 2014; pp. 63–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.H. A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Cat. Sel. Doc. Psychol. 1980, 10, 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- Malti, T.; Dys, S.P.; Colasante, T.; Peplak, J. Emotions and morality. In New Perspectives on Moral Development; Helwig, C., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuffianò, A.; Colasante, T.; Buchmann, M.; Malti, T. The Co-development of sympathy and overt aggression from middle childhood to early adolescence. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 54, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van IJzendoorn, M.H. Attachment, emergent morality, and aggression: Toward a developmental socioemotional model of antisocial behavior. International. J. Behav. Dev. 1997, 21, 703–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Young, A.L.; Sato, S. Emotional empathy and associated individual differences. Curr. Psychol. Res. Rev. 1988, 7, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, P.C.; Fuendeling, J.M. The relations among varieties of adult attachment and the components of empathy. J. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 145, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.H.; Oathout, H.A. Maintenance of satisfaction in romantic relationships: Empathy and relational competence. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 53, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Miller, P.A. The relation of empathy to prosocial and related behaviors. Psychol. Bull. 1987, 101, 91–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, M.L. Empathy and justice motivation. Motiv. Emot. 1990, 14, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.A.; Eisenberg, N. The relation of empathy to aggressive and externalizing/antisocial behavior. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 324–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J.P.; Tracy, J.L. Self-conscious emotions. In Handbook of Self and Identity; Leary, M.R., Tangney, J.P., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 446–478. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, H.B. Shame and Guilt in Neurosis; International Universities Press: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, J.L.; Robins, R.W. Putting the self into self-conscious emotions: A theoretical model. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P. The evolution of social attractiveness and its role in shame, humiliation, guilt and therapy. Br. J. Med Psychol. 1997, 70, 113–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J.P. Moral affect: The good, the bad, and the ugly. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 61, 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuewig, J.; Tangney, J.P.; Heigel, C.; Harty, L.; McCloskey, L. Shaming, blaming, and maiming: Functional links among the moral emotions, externalization of blame, and aggression. J. Res. Personal. 2010, 44, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tangney, J.P.; Wagner, P.E.; Hill-Barlow, D.; Marschall, D.E.; Gramzow, R. Relation of shame and guilt to constructive versus destructive responses to anger across the lifespan. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 797–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wall, C.; Baumeister, R.; Chester, D. Bushman How often does currently felt emotion predict social behavior and judgment? A meta-analytic test of two theories. Emot. Rev. 2016, 8, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malti, T. Toward an integrated clinical-developmental model of guilt. Dev. Rev. 2016, 39, 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, E.; Hay, D.; Richters, J. Infant-parent attachment and the origins of prosocial and antisocial behavior. In Development of Antisocial and Prosocial Behavior. Research, Theories, and Issues; Olweus, D., Block, J., Radke-Yarrow, M., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Waters, E.; Kondo-Ikemura, K.; Posada, G.; Richters, J.E. Learning to love: Milestones and mechanisms. In The Minnesota Symposia on Child Psychology (Vol. 23): Self Processes in Development; Gunnar, M., Sroufe, L.A., Eds.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1991; pp. 217–255. Available online: http://www.psychology.sunysb.edu/attachment/online/love2002.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- Gomes, A.M.; Costa Martins, M.; Farinha, M.; Silva, B.; Ferreira, E.; Castro Caldas, A.; Brandão, T. Bullying’s negative effect on academic achievement. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 9, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2020, 18, e1003583. Available online: http://www.prisma-statement.org/PRISMAStatement/ (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss: Vol. 1. Attachment, 2nd ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1982; (Original work published 1969). [Google Scholar]

- McAuliffe, W. Do emotions play an essential role in moral judgments? Think. Reason. 2019, 25, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feder, M.M.; Diamond, G.M. Parent-therapist alliance and parent attachment-promoting behavior in attachment-based family therapy for suicidal and depressed adolescents. J. Fam. Ther. 2016, 38, 82–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rious, J.B.; Cunningham, M. Altruism as a buffer for antisocial behavior for African American adolescents exposed to community violence. J. Community Psychol. 2015, 6, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardenghi, S.; Rampoldi, G.; Bani, M.; Strepparava, M.G. Attachment styles as predictors of self-reported empathy in medical students during pre-clinical years. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 965–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J.B.; Hoicowitz, T. Attachment contexts of adolescent friendship and romance. J. Adolesc. 2004, 27, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kochanska, G. Relational antecedents and social implications of the emotion of empathy: Evidence from three studies. Emotion 2017, 17, 981–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, E.; Deane, K. Defining and assessing individual differences in attachment relationships: Q-methodology and the organization of behavior in infancy and early childhood. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 1985, 50, 41–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kochanska, G.; Koenig, J.L.; Barry, R.A.; Kim, S.; Yoon, J.E. Children’s conscience during toddler and preschool years, moral self, and a competent, adaptive developmental trajectory. Dev. Psychol. 2010, 46, 1320–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laible, D. Attachment with parents and peers in late adolescence: Links with emotional competence and social behavior. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2007, 43, 1185–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armsden, G.C.; Greenberg, M.T. The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 1987, 16, 427–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muris, P.; Mayer, B.; Meesters, C. Self-reported attachment style, anxiety, and depression in children. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2000, 28, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegge, H.; Ferguson, T.J. Self-Conscious Emotions Maladaptive and Adaptive Scales (SCEMAS); Free University of Amsterdam and Logan, Utah State University: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P.; Laible, D.J.; Augustine, M.; Robeson, L. Attachment’s links with adolescents’ social emotions: The roles of negative emotionality and emotion regulation. J. Genet. Psychol. 2015, 176, 315–329, ISSN 0022-1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richaud, M.C.; Sacchi, C.; Moreno, J.E.; Oros, L. Tipos de influencia parental, socialización y afrontamiento de la amenaza en la infancia. In Primer Informe del Subsidio de la Agencia Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología y—PICT 1999 04-06300; Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Paez, A.E.; Ulagnero, C.A.; Jofré, M.J.; De Bortoli, M.A. Análisis de la estructura y consistencia interna de la adaptación española del Índice de Reactividad Interpersonal en alumnos de segundo y tercer año de polimodal. In Proceedings of the III Encuentro Interamericano de Salud Mental, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina, 19–21 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska, G.; DeVet, K.; Goldman, M.; Murray, K.; Putnam, S.P. Maternal reports of conscience development and temperament in young children. Child Dev. 1994, 65, 852–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, B. An index of empathy for children and adolescents. Child Dev. 1982, 53, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ştefan, C.A.; Avram, J. The multifaceted role of attachment during preschool: Moderator of its indirect effect on empathy through emotion regulation. Early Child Dev. Care 2018, 188, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretherton, I.; Ridgeway, D.; Cassidy, J. Assessing internal working models of the attachment relation: An attachment story completion task for 3-year-olds. In Attachment in the Preschool Years: Theory, Research, and Intervention; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1990; pp. 273–308. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, C.; Davis, H.; Horlin, C.; Anderson, M.; Baughman, N.; Campbell, C. The kids’ empathic development scale (KEDS): A multi-dimensional measure of empathy in primary school-aged children. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2013, 31, 231–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, J.; Costello, M.; Kansky, J.; Fowler, C.; Loeb, E.M.; Allen, J.P. Here for You: Attachment and the growth of empathic support for friends in adolescence. Child Dev. 2021, 1–16, ISSN 0009-3920, Online ISSN 1467-8624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, C.; Kaplan, N.; Main, M. Adult Attachment Interview, 3rd ed.; Unpublished manuscript; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kobak, R.R.; Cole, H.; Ferenz-Gillies, R.; Fleming, W.; Gamble, W. Attachment and emotion regulation during mother-teen problem-solving: A control theory analysis. Child Dev. 1993, 64, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malti, T.; Eisenberg, N.; Kim, H.; Buchmann, M. Developmental trajectories of sympathy, moral emotion attributions, and moral reasoning: The role of parental support. Soc. Dev. 2013, 22, 773–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malti, T.; Ongley, S.; Peplak, J.; Chaparro, M.; Buchmann, M.; Zuffianò, A.; Cui, L. Children’s Sympathy, Guilt, and Moral Reasoning in Helping, Cooperation, and Sharing: A 6-Year Longitudinal Study. Child Dev. 2016, 87, 1783–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, M.M.; Thibodeau, R.B.; Pierucci, J.M.; Gilpin, A.T. Supporting the development of empathy: The role of theory of mind and fantasy orientation. Soc. Dev. 2017, 26, 951–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plousia, M. Individual differences in children’s understanding of guilt: Links with Theory of Mind. J. Genet. Psychol. 2018, 179, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Empirical articles with available abstract published in peer-review journals; Articles published in Portuguese, English, French, Spanish or Italian (languages mastered by the authors); Articles examining the relationship between attachment and moral emotions and pro-sociality (e.g., sympathy and guilt, altruism); Articles with the following participants: Children and adolescents (0–19 years old). | Studies on children or adolescents not living in natural contexts (e.g., institutionalized children); Studies of moral emotions in the context of mental illness or addictive substance usage; Qualitive research; Research that does not accurately/directly evaluate parental attachment or moral emotions. Research on intervention programs; Non-peer-reviewed articles (e.g., book chapters, conference papers or posters). |

| Characteristics of the Studies | Total of Articles (n) | Percentage (%) | Articles ID a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical background: | |||

| 10 | 100% | 1–10. |

| Type of data: | |||

| 10 | 100% | 1–10. |

| 0 | 0% | - |

| Study design b | |||

| 4 | 40% | 1, 2, 9, 10. |

| 6 | 60% | 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9. |

| Assessment of moral emotions | |||

| 7 | 63.64% | 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9. |

| 2 | 18.18% | 1, 7. |

| 2 | 18.18% | 2, 10. |

| Assessment of attachment | |||

| 7 | 63.64% | 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9. |

| 2 | 18.18% | 2, 7. |

| 2 | 18.18% | 2, 10. |

| Sample characteristics | nb | % | ID a |

| Country of origin | |||

| 7 | 63.64% | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 9. |

| 3 | 27.27% | 4, 8, 10. |

| 1 | 18.18% | 6. |

| Age | |||

| 5 | 45.45% | 2, 4, 7, 8, 10. |

| 6 | 54.55% | 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9. |

| Social economic status | |||

| 6 | 50% | 1, 2, 4, 8, 9, 10. |

| 2 | 16.67% | 1,4. |

| 4 | 33.33% | 3, 5, 6, 7. |

| Characteristics of the assessment of moral emotions | nb | % | ID a |

| 9 | 69.23% | 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10. |

| 0 | 0% | - |

| 2 | 15.38% | 4, 5. |

| 0 | 0% | - |

| Others moral emotions: | |||

| 1 | 7.69% | 5. |

| 1 | 7.69% | 4. |

| ID. Authors (Date) | N | M Age (SD) | Ethnicity | Attachment Measure | Moral Emotion Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Diamond et al. (2012) [12] | 103 (mother–adolscent dyads) | NA (14 years old) | 82% Caucasian, 3% African American, 1% Asian, 7% Latino, 7% another or mixed ethnicity. | Adolescent Attachment Scale [51]. | Empathy: During the re-viewing of their discussion task, participants rated positive and negative affect (5-point scale [11]). |

| 2. Kim and Kochanska (2017): Family study [52] | 101 families | NA | - | Strange Situation and Attachment Q-Set version 3.0 [53]. | Empathy: Paradigm [54]. |

| Laible (2007) [55]. | 117 | 19.6 years (1.41). | 78% Caucasians | Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA) [56]. | Empathy: Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) [23]. |

| 4. Muris et al. (2014)—Study 1 [10] | 688 | 10.39 years (1.00) | Majority: European descent (i.e., Dutch). | The Attachment Questionnaire for Children [57]. | Guilt and shame: SCEMAS [58]. |

| 4. Muris et al. (2014)—Study 2 [10] | 135 | 15.46 years (1.99) | Less than 10% was non-Caucasian | IPPA [56]. | Guilt and shame: SCEMAS [58]. |

| 5. Murphy et al. (2015) [59] | 148 | 15.68 years (1.16) | 88.5% Caucasian, 5.4% Hispanic, 5.4% others | Shortened version of IPPA [56]. | Empathy: Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) [23]. |

| 6. Paez and Rovella (2019) [14] | 518 | 15.22 years (1.69) | - | Kerns Security Scale (Argentinian adaptation [60]) | Empathy: Interpersonal Reactivity Index (Argentinian adaptation) [61]. |

| 7. Panfile and Laible (2012) [6] | 63 dyads | NA (3 months of age) | 81% Caucasian. | Attachment Q-Set version 3.0 [53]. | Empathy: My Child questionnaire [62] and Bryant’s Index of Empathy [63]. |

| 8. Ştefan and Avram (2018) [64] | 212 | 56.34, months (11.52) | 92.8% Caucasian, 0.5% Gypsy and 6.7% reported no ethnicity. | Attachment Security Completation Task [65]. | Kid’s Empathic Development Scale (KEDS) [66]. |

| 9. Stern et al. (2021) [67] | 184 | 14.27 (0.77) to 18.38 years (1.04) | 58% Caucasian, 29% African American, 13% other | The Adolescent Attachment Interview [68] and Q-set [69]. | Empathy: Observed supportive behavior task (SBT) [67]. |

| 10. van der Mark (2002) [13] | 151 | 16–21 months | Mostly Caucasian | Strange situation | Empathy: observation coding system [19]. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Costa Martins, M.; Santos, A.F.; Fernandes, M.; Veríssimo, M. Attachment and the Development of Moral Emotions in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Children 2021, 8, 915. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/children8100915

Costa Martins M, Santos AF, Fernandes M, Veríssimo M. Attachment and the Development of Moral Emotions in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Children. 2021; 8(10):915. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/children8100915

Chicago/Turabian StyleCosta Martins, Mariana, Ana Filipa Santos, Marília Fernandes, and Manuela Veríssimo. 2021. "Attachment and the Development of Moral Emotions in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review" Children 8, no. 10: 915. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/children8100915