Perspectives of Black/African American and Hispanic Parents and Children Living in Under-Resourced Communities Regarding Factors That Influence Food Choices and Decisions: A Qualitative Investigation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aim

2.2. Research Design

2.3. Setting

2.4. Recruitment

2.5. Procedures

2.6. Analysis

2.6.1. Surveys

2.6.2. Interviews

2.6.3. Quotes and Photographs

3. Results

3.1. Recruitment

3.2. Language

3.3. Family/Household Characteristics

3.4. Interview Findings

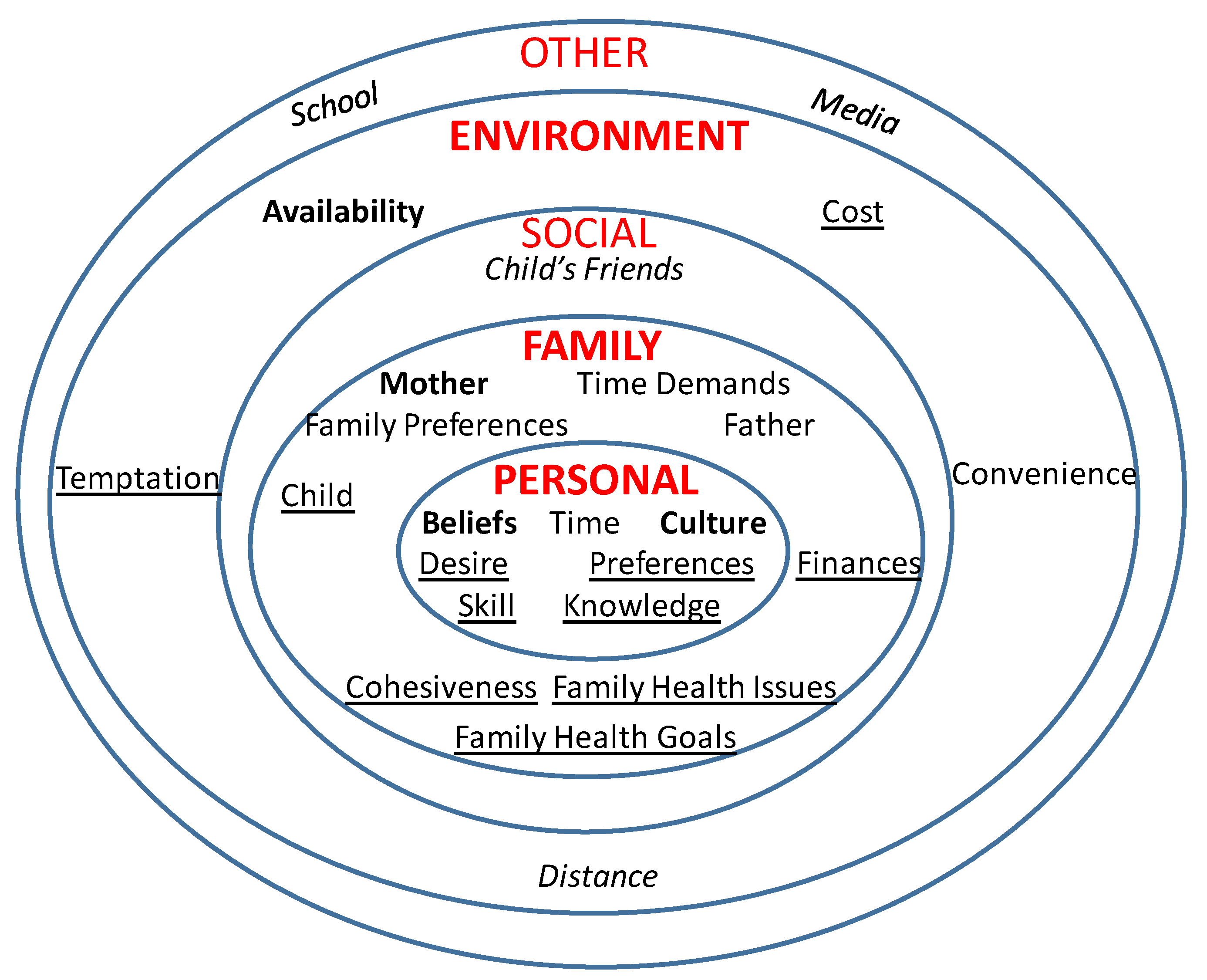

3.5. Personal Influences

3.6. Family Influences

3.7. Social Influences

3.8. Environmental Influences

3.9. Other Influences

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fryar, C.D.; Carroll, M.D.; Afful, J. Prevalence of Overweight, Obesity, and Severe Obesity among Children and Adolescents Aged 2–19 Years: United States, 1963–1965 through 2017–2018. NCHS Health E-Stats. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity-child-17-18/obesity-child.htm (accessed on 17 February 2021).

- Hales, C.M.; Carroll, M.D.; Fryar, C.D.; Ogden, C.L. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015–2016. Nchs Data Brief. 2017, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden, C.L.; Carroll, M.D.; Fakhouri, T.H.; Hales, C.M.; Fryar, C.D.; Li, X.; Freedman, D.S. Prevalence of obesity among youths by household income and education level of head of household—United States 2011–2014. Mmwr Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018, 67, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- State of Childhood Obesity. Obesity Rates for Youth Ages 10 to 17. Available online: https://stateofchildhoodobesity.org/children1017/ (accessed on 26 February 2021).

- The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth). Child Obesity in Texas: Results from the 2015–2016 School Physical Activity and Nutrition (SPAN) Survey. Available online: https://sph.uth.edu/research/centers/dell/project.htm?project=3037edaa-201e-492a-b42f-f0208ccf8b29 (accessed on 26 February 2021).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020. Available online: https://www.healthypeople.gov/ (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Mejia de Grubb, M.C.; Levine, R.S.; Zoorob, R.J. Diet and obesity issues in the underserved. Prim. Care 2017, 44, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilfley, D.E.; Saelens, B. Epidemiology and causes of obesity in children. In Eating Disorders and Obesity: A Comprehensive Handbook, 2nd ed.; Fairburn, C.G., Brownell, K.D., Eds.; The Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 429–432. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Kelly, A.S. Review of childhood obesity: From epidemiology, etiology, and comorbidities to clinical assessment and treatment. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beckerman, J.P.; Alike, Q.; Lovin, E.; Tamez, M.; Mattei, J. The development and public health implications of food preferences in children. Front. Nutr. 2017, 4, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Santiago-Torres, M.; Adams, A.K.; Carrel, A.L.; LaRowe, T.L.; Schoeller, D.A. Home food availability, parental dietary intake, and familial eating habits influence the diet quality of urban Hispanic children. Child. Obes 2014, 10, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaglioni, S.; De Cosmi, V.; Ciappolino, V.; Parazzini, F.; Brambilla, P.; Agostoni, C. Factors influencing children’s eating behaviours. Nutrients 2018, 10, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- French, S.A.; Tangney, C.C.; Crane, M.M.; Wang, Y.; Appelhans, B.M. Nutrition quality of food purchases varies by household income: The SHoPPER study. Bmc Public Health 2019, 19, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Institute of Medicine. Food Marketing to Children and Youth: Threat or Opportunity? The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lucan, S.C.; Maroko, A.R.; Sanon, O.C.; Schechter, C.B. Unhealthful food-and-beverage advertising in subway stations: Targeted marketing, vulnerable groups, dietary intake, and poor health. J. Urban. Health 2017, 94, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fleischhacker, S.E.; Evenson, K.R.; Rodriguez, D.A.; Ammerman, A.S. A systematic review of fast food access studies. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, e460–e471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hager, E.R.; Cockerham, A.; O’Reilly, N.; Harrington, D.; Harding, J.; Hurley, K.M.; Black, M.M. Food swamps and food deserts in Baltimore City, MD, USA: Associations with dietary behaviours among urban adolescent girls. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 2598–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McLeroy, K.R.; Bibeau, D.; Steckler, A.; Glanz, K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ. Q. 1988, 15, 351–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, K.K.; Birch, L.L. Childhood overweight: A contextual model and recommendations for future research. Obes. Rev. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 2001, 2, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohri-Vachaspati, P.; DeLia, D.; DeWeese, R.S.; Crespo, N.C.; Todd, M.; Yedidia, M.J. The relative contribution of layers of the Social Ecological Model to childhood obesity. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2055–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jernigan, J.; Kettel Khan, L.; Dooyema, C.; Ottley, P.; Harris, C.; Dawkins-Lyn, N.; Kauh, T.; Young-Hyman, D. Childhood Obesity Declines Project: Highlights of community strategies and policies. Child. Obes 2018, 14, S32–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; U.S. Department of Agriculture. Everyone has a role in supporting healthy eating patterns: The Social-Ecological Model. In Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015–2020, 8th ed.; 2015. Available online: https://health.gov/our-work/food-nutrition/previous-dietary-guidelines/2015 (accessed on 26 February 2021).

- Fiese, B.H.; Jones, B.L. Food and family: A socio-ecological perspective for child development. Adv. Child Dev. Behav. 2012, 42, 307–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, R.A. Complex systems modeling for obesity research. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2009, 6, A97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harrison, K.; Bost, K.K.; McBride, B.A.; Donovan, S.M.; Grigsby-Toussaint, D.S.; Kim, J.; Liechty, J.M.; Wiley, A.; Teran-Garcia, M.; Jacobsohn, G.C. Toward a developmental conceptualization of contributors to overweight and obesity in childhood: The Six-Cs model. Child. Dev. Perspect. 2011, 5, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.E.; Ray, W.A. Family systems theory. In Encyclopedia of Family Studies; Shehan, C.L., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, J.S.; Fisher, J.O.; Birch, L.L. Parental influence on eating behavior: Conception to adolescence. J. LawMed. Ethics A J. Am. Soc. LawMed. Ethics 2007, 35, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reczek, C. Conducting a multi family member interview study. Fam. Process 2014, 53, 318–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Qualitative Research from Start to Finish, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, D. Talk to me, please! The importance of qualitative research to games for health. Games Health J. 2014, 3, 117–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSmet, A.; Palmeira, A.; Beltran, A.; Brand, L.; Davies, V.F.; Thompson, D. The yin and yang of formative research in designing serious (exer-)games. Games Health J. 2015, 4, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, D.; Bhatt, R.; Watson, K. Physical activity problem-solving inventory for adolescents: Development and initial validation. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2013, 25, 448–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.; Mahabir, R.; Bhatt, R.; Boutte, C.; Cantu, D.; Vazquez, I.; Callender, C.; Cullen, K.; Baranowski, T.; Liu, Y.; et al. Butterfly Girls; promoting healthy diet and physical activity to young African American girls online: Rationale and design. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thompson, D.; Cullen, K.W.; Boushey, C.; Konzelmann, K. Design of a website on nutrition and physical activity for adolescents: Results from formative research. J. Med. Internet Res. 2012, 14, e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, D.; Cantu, D.; Ramirez, B.; Cullen, K.W.; Baranowski, T.; Mendoza, J.; Anderson, B.; Jago, R.; Rodgers, W.; Liu, Y. Texting to increase adolescent physical activity: Feasibility assessment. Am. J. Health Behav. 2016, 40, 472–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dave, J.M.; Thompson, D.I.; Svendsen-Sanchez, A.; Cullen, K.W. Perspectives on barriers to eating healthy among food pantry clients. Health Equity 2017, 1, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Noia, J.; Monica, D.; Cullen, K.W.; Thompson, D. Perceived influences on farmers’ market use among urban, WIC-enrolled women. Am. J. Health Behav. 2017, 41, 618–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Burris, M.A. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ. Behav. 1997, 24, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oates, G.R.; Phillips, J.M.; Bateman, L.B.; Baskin, M.L.; Fouad, M.N.; Scarinci, I.C. Determinants of obesity in two urban communities: Perceptions and community-driven solutions. Ethn. Dis. 2018, 28, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nykiforuk, C.I.; Vallianatos, H.; Nieuwendyk, L.M. Photovoice as a method for revealing community perceptions of the built and social environment. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2011, 10, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, C.; Fleury, J.; Rivera, A. Visual methods in the assessment of diet intake in Mexican American women. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2007, 29, 758–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, S.; White, M.; Wrieden, W.; Brown, H.; Stead, M.; Adams, J. Home food preparation practices, experiences and perceptions: A qualitative interview study with photo-elicitation. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laraia, B.A.; Leak, T.M.; Tester, J.M.; Leung, C.W. Biobehavioral factors that shape nutrition in low-income populations: A narrative review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 52, S118–S126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thompson, D.; Bhatt, R.; Vazquez, I.; Cullen, K.W.; Baranowski, J.; Baranowski, T.; Liu, Y. Creating action plans in a serious video game increases and maintains child fruit-vegetable intake: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thompson, D.; Baranowski, T.; Buday, R.; Baranowski, J.; Juliano, M.; Frazior, M.; Wilsdon, J.; Jago, R. In pursuit of change: Youth response to intensive goal setting embedded in a serious videogame. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2007, 1, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Turner, J.J.; Kelly, J.; McKenna, K. Food for thought: Parents’ perspectives of child influence. Br. Food J. 2006, 108, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callender, C.; Thompson, D. Family TXT: Feasibility and acceptability of a mHealth obesity prevention program for parents of pre-adolescent African American girls. Children 2018, 5, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bickel, G.; Nord, M.; Price, C.; Hamilton, W.; Cook, J. Guide to Measuring Household Food Security, Revised 2000; USDA/Food and Nutrition Service: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2000.

- Woolford, S.J.; Khan, S.; Barr, K.L.; Clark, S.J.; Strecher, V.J.; Resnicow, K. A picture may be worth a thousand texts: Obese adolescents’ perspectives on a modified photovoice activity to aid weight loss. Child. Obes. 2012, 8, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.S.; Woo, J. Prevention of overweight and obesity: How effective is the current public health approach. Int J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2010, 7, 765–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Travert, A.S.; Sidney Annerstedt, K.; Daivadanam, M. Built environment and health behaviors: Deconstructing the black box of interactions—A review of reviews. Int J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lakshman, R.; Mazarello Paes, V.; Hesketh, K.; O’Malley, C.; Moore, H.; Ong, K.; Griffin, S.; van Sluijs, E.; Summerbell, C. Protocol for systematic reviews of determinants/correlates of obesity-related dietary and physical activity behaviors in young children (preschool 0 to 6 years): Evidence mapping and syntheses. Syst. Rev. 2013, 2, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Emilien, C.; Hollis, J.H. A brief review of salient factors influencing adult eating behaviour. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2017, 30, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J.; Pratt, C.; Boyington, J.; Nelson, C.; Truesdale, K.P.; Ward, D.S.; Lytle, L.; Sherwood, N.E.; Robinson, T.N.; Moore, S.; et al. Multilevel interventions targeting obesity: Research recommendations for vulnerable populations. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 52, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pereira, M.; Padez, C.M.P.; Nogueira, H. Describing studies on childhood obesity determinants by Socio-Ecological Model level: A scoping review to identify gaps and provide guidance for future research. Int. J. Obes. 2019, 43, 1883–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, A.P.; D’Onise, K.; McDermott, R.; Vally, H.; O’Dea, K. How effective are family-based and institutional nutrition interventions in improving children’s diet and health? A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Padgett, D.K. Telling the story: Writing up the qualitative study. In Qualitative and Mixed Methods in Public Health; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 221–238. [Google Scholar]

- Fish, C.A.; Brown, J.R.; Quandt, S.A. African American and Latino low income families’ food shopping behaviors: Promoting fruit and vegetable consumption and use of alternative healthy food options. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2015, 17, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelson, M.L. The impact of culture on food-related behavior. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1986, 6, 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Airhihenbuwa, C.O.; Kumanyika, S.; Agurs, T.D.; Lowe, A.; Saunders, D.; Morssink, C.B. Cultural aspects of African American eating patterns. Ethn. Health 1996, 1, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, D.C. Factors influencing food choices, dietary intake, and nutrition-related attitudes among African Americans: Application of a culturally sensitive model. Ethn. Health 2004, 9, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumanyika, S.; Taylor, W.C.; Grier, S.A.; Lassiter, V.; Lancaster, K.J.; Morssink, C.B.; Renzaho, A.M. Community energy balance: A framework for contextualizing cultural influences on high risk of obesity in ethnic minority populations. Prev. Med. 2012, 55, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, A.S.; Golash-Boza, T.; Unger, J.B.; Baezconde-Garbanati, L. Questioning the dietary acculturation paradox: A mixed-methods study of the relationship between food and ethnic identity in a group of Mexican-American women. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Counihan, C.M. A Tortilla Is Like Life: Food and Culture in the San Luis Valley of Colorado; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Callender, C.; Thompson, D. Text messaging based obesity prevention program for parents of pre-adolescent African American girls. Children 2017, 4, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Satia, J.A. Diet-related disparities: Understanding the problem and accelerating solutions. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Cosmi, V.; Scaglioni, S.; Agostoni, C. Early taste experiences and later food choices. Nutrients 2017, 9, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mennella, J.A.; Bobowski, N.K. The sweetness and bitterness of childhood: Insights from basic research on taste preferences. Physiol. Behav. 2015, 152, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gahagan, S. Development of eating behavior: Biology and context. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2012, 33, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faith, M.S. Development and modification of child food preferences and eating patterns: Behavior genetics strategies. Int. J. Obes. 2005, 29, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Birch, L.L.; McPhee, L.; Shoba, B.C.; Pirok, E.; Steinberg, L. What kind of exposure reduces children’s food neophobia? Looking vs. tasting. Appetite 1987, 9, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura Paroche, M.; Caton, S.J.; Vereijken, C.; Weenen, H.; Houston-Price, C. How infants and young children learn about food: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vollmer, R.L.; Adamsons, K.; Foster, J.S.; Mobley, A.R. Association of fathers’ feeding practices and feeding style on preschool age children’s diet quality, eating behavior and body mass index. Appetite 2015, 89, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, D.; Cullen, K.W.; Reed, D.B.; Konzelmann, K.; Smalling, A.L. Formative assessment in the development of an obesity prevention component for the Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program in Texas. Fam Community Health 2011, 34, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Story, M.; Kaphingst, K.M.; Robinson-O’Brien, R.; Glanz, K. Creating healthy food and eating environments: Policy and environmental approaches. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2008, 29, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gruber, K.J.; Haldeman, L.A. Using the family to combat childhood and adult obesity. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2009, 6, A106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kelishadi, R.; Azizi-Soleiman, F. Controlling childhood obesity: A systematic review on strategies and challenges. J. Res. Med. Sci. Off. J. Isfahan Univ. Med. Sci. 2014, 19, 993–1008. [Google Scholar]

- Kumanyika, S.K. A framework for increasing equity impact in obesity prevention. Am. J. Public Health 2019, 109, 1350–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- InterQ Research. Determining Sample Size for Qualitative Research: What is the Magical Number? Available online: https://interq-research.com/determining-sample-size-for-qualitative-research-what-is-the-magical-number/#:~:text=Our%20general%20recommendation%20for%20in,the%20population%20integrity%20in%20recruiting (accessed on 10 February 2021).

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent (n = 18) | |||

| Age (years) | |||

| 30–39 | 4 | 22.2 | |

| 40–49 | 11 | 61.1 | |

| 50–59 | 2 | 11.1 | |

| ≥60 | 1 | 5.6 | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Female | 18 | 100.0 | |

| Hispanic | |||

| Yes | 8 | 44.4 | |

| No | 10 | 55.6 | |

| Race | |||

| Black/African American | 10 | 55.6 | |

| White | 6 | 33.3 | |

| Other | 2 | 11.1 | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married/living with significant other | 11 | 61.1 | |

| Single, never married | 3 | 16.7 | |

| Divorced, separated, widowed | 3 | 16.7 | |

| Other | 1 | 5.6 | |

| Child (n = 18) | |||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 8 | 44.4 | |

| Female | 10 | 55.6 | |

| Hispanic | |||

| Yes | 9 | 50.0 | |

| No | 9 | 50.0 | |

| Race | |||

| Black/African American | 10 | 55.6 | |

| White | 6 | 33.3 | |

| Other | 2 | 11.1 | |

| School lunch | |||

| Receives free school lunch | 12 | 66.7 | |

| Receives reduced price lunch | 5 | 27.8 | |

| Pays full price for school lunch | 1 | 5.6 | |

| Household | |||

| Number of children < 18 years old in home | |||

| 1 | 1 | 5.6 | |

| 2 | 9 | 50.0 | |

| 3 | 7 | 38.9 | |

| 4 | 1 | 5.6 | |

| Number of adults in home, excluding you | |||

| 0 | 2 | 11.1 | |

| 1 | 7 | 38.9 | |

| 2 | 5 | 27.8 | |

| 3 | 3 | 16.7 | |

| 4 | 1 | 5.6 | |

| Highest household education | |||

| Some high school | 2 | 11.1 | |

| High school graduate/GED | 1 | 5.6 | |

| Technical school | 3 | 16.7 | |

| Some college | 6 | 33.3 | |

| College graduate | 4 | 22.2 | |

| Post graduate study | 2 | 11.1 | |

| Average annual household income | |||

| <$21,000 | 4 | 22.2 | |

| $21,000–$41,000 | 8 | 44.4 | |

| $42,000–$61,000 | 5 | 27.78 | |

| >$61,000 | 1 | 5.6 | |

| Food security | |||

| High/marginal food security | 16 | 88.9 | |

| Low food security | 1 | 5.6 | |

| Very low food security | 1 | 5.6 | |

| Parent food assistance program * usage | |||

| 0 program participation | 6 | 33.3 | |

| 1–3 programs | 12 | 66.7 | |

| Level | Parent | Child |

|---|---|---|

| Personal | Beliefs | |

| Culture | ||

| Family | Mother | Mother |

| Social | ||

| Environment | Availability | Home foods |

| Other |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thompson, D.; Callender, C.; Velazquez, D.; Adera, M.; Dave, J.M.; Olvera, N.; Chen, T.-A.; Goldsworthy, N. Perspectives of Black/African American and Hispanic Parents and Children Living in Under-Resourced Communities Regarding Factors That Influence Food Choices and Decisions: A Qualitative Investigation. Children 2021, 8, 236. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/children8030236

Thompson D, Callender C, Velazquez D, Adera M, Dave JM, Olvera N, Chen T-A, Goldsworthy N. Perspectives of Black/African American and Hispanic Parents and Children Living in Under-Resourced Communities Regarding Factors That Influence Food Choices and Decisions: A Qualitative Investigation. Children. 2021; 8(3):236. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/children8030236

Chicago/Turabian StyleThompson, Debbe, Chishinga Callender, Denisse Velazquez, Meheret Adera, Jayna M. Dave, Norma Olvera, Tzu-An Chen, and Natalie Goldsworthy. 2021. "Perspectives of Black/African American and Hispanic Parents and Children Living in Under-Resourced Communities Regarding Factors That Influence Food Choices and Decisions: A Qualitative Investigation" Children 8, no. 3: 236. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/children8030236