Tracking the 6-DOF Flight Trajectory of Windborne Debris Using Stereophotogrammetry

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

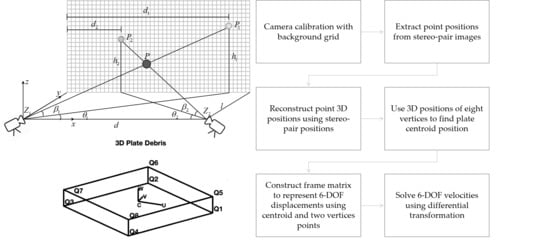

Problem Formulation and Notation

| , | –points at the lens positions of two cameras |

| –position of a point debris | |

| , | –projected locations of the debris on the grid wall seen from two cameras (i.e., a stereopair), respectively |

| –distance between cameras | |

| –distance between camera lens and the wall along the y-direction; the wall is parallel to the z‒x plane | |

| , | –distances of points on the wall along the x-axis from the y-axis |

| , | –heights of points on the wall along the z-axis from the x‒y plane |

| , | –angles that , rays make with the x‒y plane |

| , | –angles between the x-axis and the projections of , rays on the x‒y plane |

3. Debris Position and Spatial Orientation (6-DOF) in 3D Space

3.1. The 2D Stereopairs’ Positions

3.2. The Relationship between the 3D Spatial Position of Debris and the 2D Stereopairs’ Positions

3.3. Explicit Expressions of Debris Position in 3D Space

3.4. Cartesian Position and Orientation for Thin Plate Debris

3.5. Three-Degree-of-Freedom (3-DOF) Frames in Universal Coordinate System

3.6. Differential Operators for 6-DOF Motion

4. 6-DOF Motion Consideration

4.1. Motivation

4.2. The Relationship between Differential Transformations in Universal and Local Coordinate Systems

4.2.1. General Transformation

4.2.2. Rotational Differential Transform with Respect to Universal Coordinate System

4.2.3. Differential Transform in Universal Coordinate System

4.2.4. Differential Transform in Local Coordinate System

- Show that the rotation differential operator with respect to the local frame system, such thatProof.□

- Show that the linear differential in the local frame simplifies toProof.□

- Differential operator with respect to local frame coordinate system.Theorem 1.The frame differential transformation matrixin the local coordinate system iswhere, .Proof.From (Section 4.2.1) and (Equation (34)), we getHence, the theorem is proved. □

5. 6-DOF Motion Trajectory with Velocity

5.1. Velocity

5.2. Experimenting with 6DOF Position and Orientation and 6DOF Motion Methods

5.3. Implementation Procedure for Debris Tracking with Both Displacement and Velocity Time Histories Determined

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Holmes, J.D. Windborne debris and damage risk models: A review. Wind Struct. 2010, 13, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minor, J.E. Lessons learned from failures of the building envelope in windstorms. J. Archit. Eng. 2005, 11, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.E.; Wills, J. Vulnerability of fully glazed high-rise buildings in tropical cyclones. J. Archit. Eng. 2002, 8, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behr, R.A.; Minor, J.E. A survey of glazing system behavior in multi-story buildings during hurricane andrew. Struct. Des. Tall Build. 1994, 3, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, P.R.; Schiff, S.D.; Reinhold, T.A. Wind damage to envelopes of houses and consequent insurance losses. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 1994, 53, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dade County. Building Code Evaluation Task Force Final Report; Dade County: Miami, FL, USA, 1992.

- Dade County. Final Report of the Dade County Grand Jury, Dade County Grand Jury—Spring Term A.D. 1992; Dade County: Miami, FL, USA, 1992.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency. Building Performance: Hurricane Andrew in Florida; Federal Insurance Administration, FEMA: Washington, DC, USA, 1992.

- Wind Engineering Research Council (WERC). Preliminary Observations of WERC Post-Disaster Team; Wind Engineering Research Council (WERC): College Station, TX, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, C.; Hanson, C. Failure of residential building envelopes as a result of Hurricane Andrew in Dade County, Florida. In Hurricanes of 1992: Lessons Learned and Implications for the Future; Cook, R.A., Soltani, M., Eds.; ASCE: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 496–508. [Google Scholar]

- Beason, W.L.; Meyers Gerald, E.; James Ray, W. Hurricane related Window glass damage in Houston. J. Struct. Eng. 1984, 110, 2843–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachikawa, M. Trajectories of flat plates in uniform flow with application to wind-generated missiles. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 1983, 14, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Letchford, C.; Holmes, J. Investigation of plate-type windborne debris. Part I. Experiments in wind tunnel and full scale. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2006, 94, 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Holmes, J.D.; Letchford, C.W. Trajectories of wind-borne debris in horizontal winds and applications to impact testing. J. Struct. Eng. 2007, 133, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A. Wind borne debris impact generated damage to cladding of high-rise building. In Proceedings of the 12th Americas Conference on Wind Engineering (12ACWE), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–20 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Visscher, B.T.; Kopp, G.A. Trajectories of roof sheathing panels under high winds. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2007, 95, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordi, B.; Kopp, G.A. Effects of initial conditions on the flight of windborne plate debris. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2011, 99, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordi, B.; Traczuk, G.; Kopp, G.A. Effects of wind direction on the flight trajectories of roof sheathing panels under high winds. Wind Struct. 2010, 13, 145–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, K. Experimental and Analytical Trajectories of Simplified Debris Models in Tornado Winds. Master’s Thesis, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, J.F.; Dam, A.V.; McGuire, M.; Sklar, D.F.; Foley, J.D.; Feiner, S.K.; Akler, K. Computer Graphics: Principle and Practice, 3rd ed.; Addison Wesley Professional: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Niku, S.B. Introduction to Robotics Analysis, Control, Applications, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sabharwal, C.L.; Guo, Y. Tracking the 6-DOF Flight Trajectory of Windborne Debris Using Stereophotogrammetry. Infrastructures 2019, 4, 66. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/infrastructures4040066

Sabharwal CL, Guo Y. Tracking the 6-DOF Flight Trajectory of Windborne Debris Using Stereophotogrammetry. Infrastructures. 2019; 4(4):66. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/infrastructures4040066

Chicago/Turabian StyleSabharwal, Chaman Lal, and Yanlin Guo. 2019. "Tracking the 6-DOF Flight Trajectory of Windborne Debris Using Stereophotogrammetry" Infrastructures 4, no. 4: 66. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/infrastructures4040066