Prevailing Approaches and Practices of Citizen Participation in Smart City Projects: Lessons from Trondheim, Norway

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Emergence of Citizen-Centric Approach into the Smart City

- To empirically make sense of citizen participation and potential pitfalls within the smart city projects;

- to interrogate the framing and role of citizens in the process of developing and implementing smart initiatives.

2.1. Conceptualization of Citizen Participation

2.1.1. Approaches

Participatory versus Deliberative Democracy

Input versus Output Legitimacy

Direct versus Indirect Participation

2.2. Practices

2.3. Influences on Prevailing Approaches and Practices

2.4. Citizen Participation in Norway

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Approach

- The characteristics of citizen participation in Trondheim’s policy-making processes,

- The meanings that the participants themselves attribute to these interactions,

- What is/was happening in relation to citizen participation at the moment,

- What structures and processes have inhibited or reinforced the prevailing approaches and practices, including the complexity of social and political interactions [48].

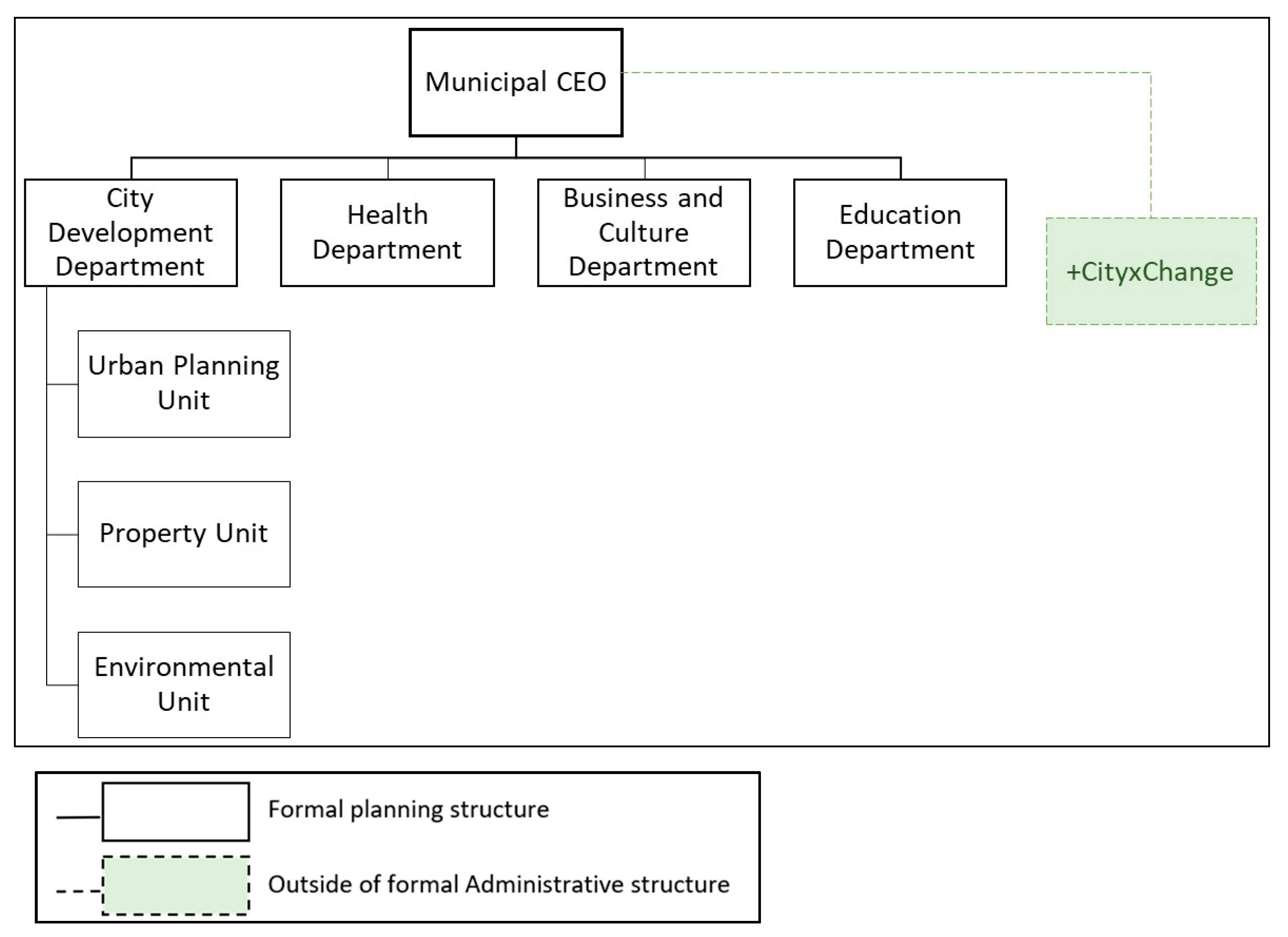

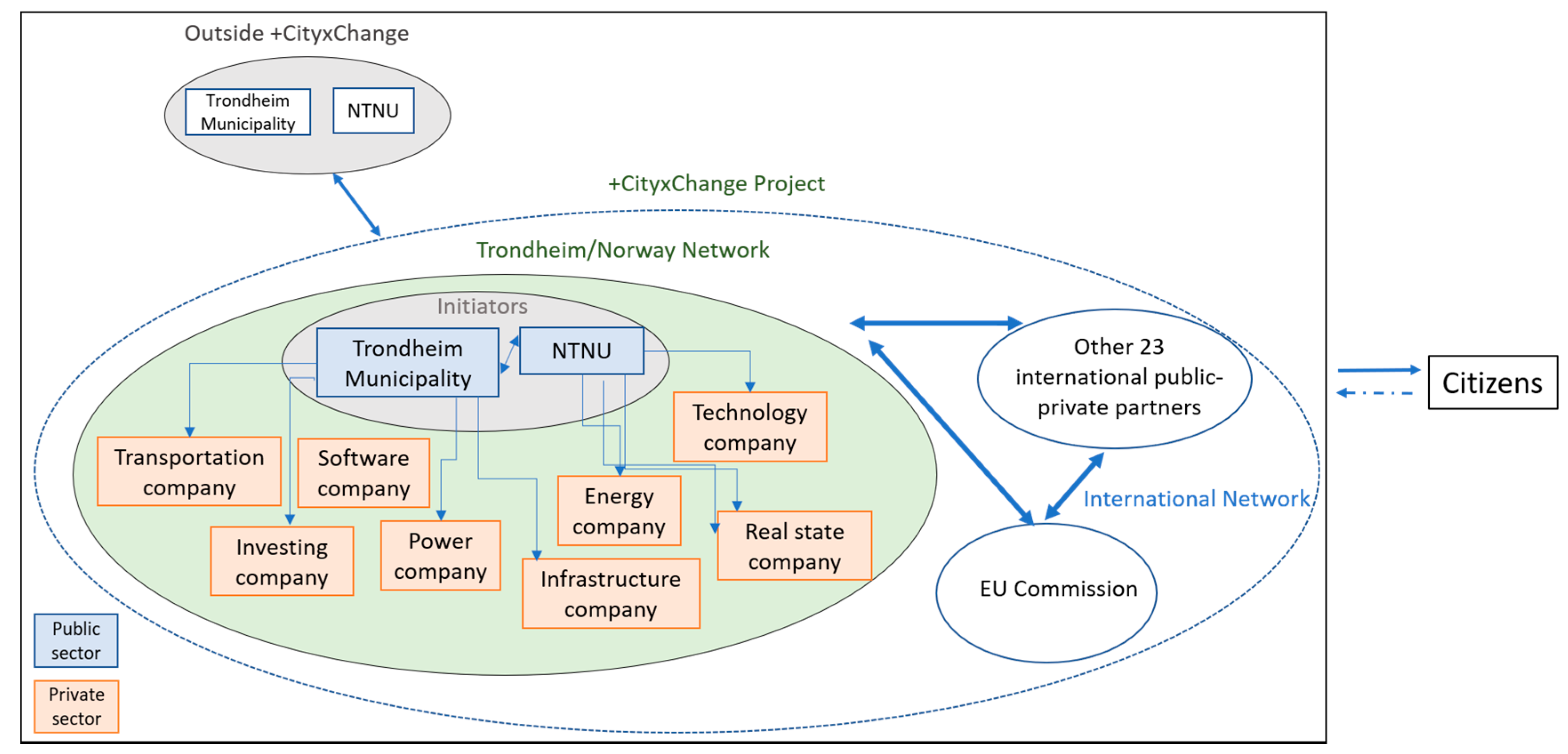

+CityxChange Pilot Project in Trondheim

- Enabling citizen participation and ownership for solutions for the transformation toward a positive energy city;

- Developing a Bold City Vision 2050 and guidelines that create and trigger an integrated approach to sustainable urban development, citizen/private company/NGO integrated processes, and a way ahead that ensures inclusion;

- Co-creating distributed positive-energy blocks through citizen participation,creating a citizen-participation playbook and platform.

3.2. Research Methods

- What are the prevailing approaches, understandings and practices in relation to citizen participation amongst the key actors involved +CityxChange?

- Which structures and processes have influenced the prevailing approaches and practices?

- How do you define the smart city?

- What are the main objectives of +CityxChange?

- What does citizen participation mean in your opinion? What can we do to improve it?

- Have you heard about the smart city? Do you know that Trondheim wants to become smart?

- How do you evaluate the citizen participation in Trondheim?

- What is or should be the role of citizens?

- How can citizens better participate in the urban development process? Are the prevailing practices of authorities satisfactory?

3.3. Limitations of the Study

4. Findings and Discussion

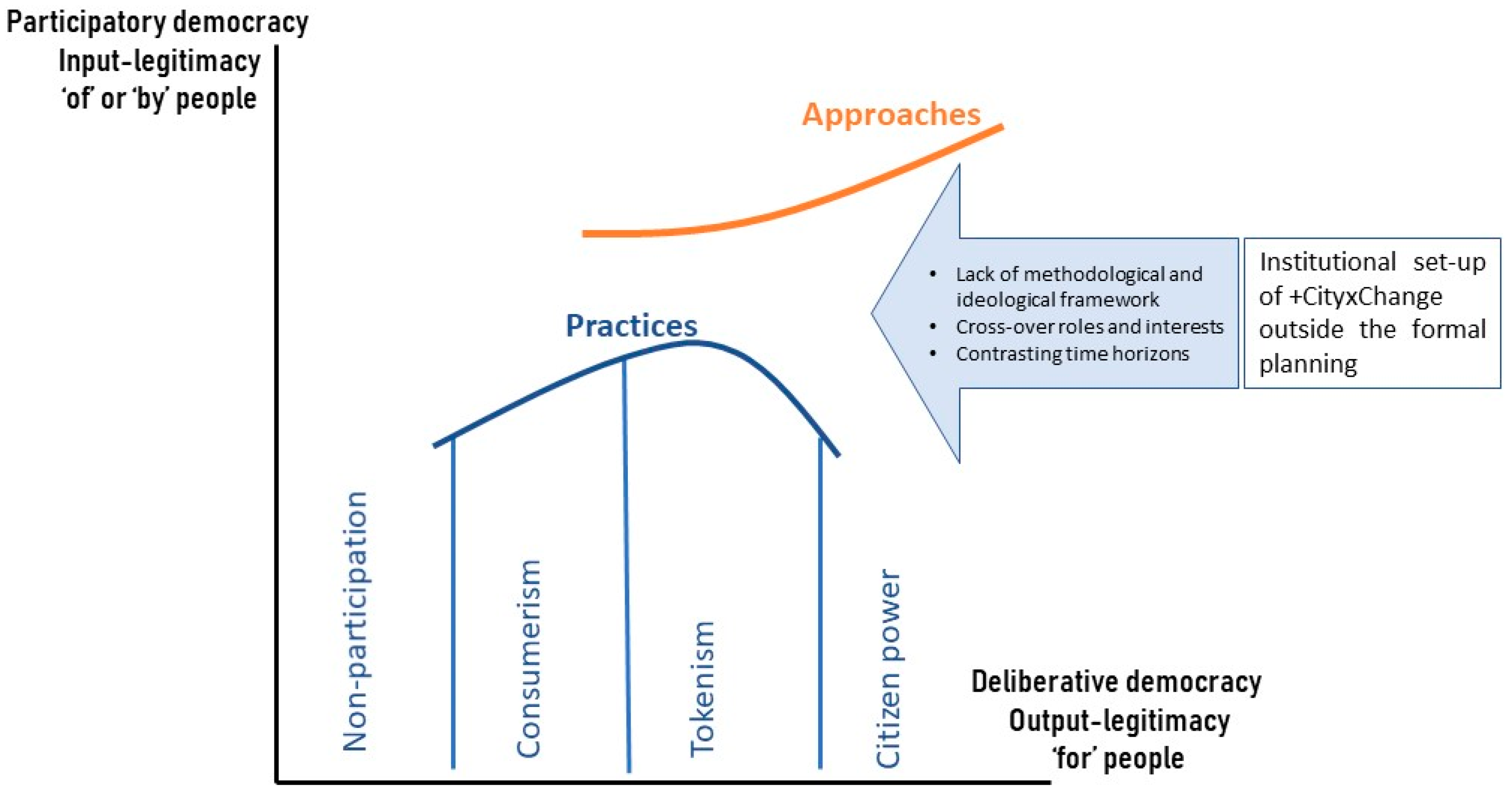

4.1. Prevailing Approaches, Understandings, and Practices in Relation to Citizen Participation amongst the Key Actors Involved in +CityxChange

4.2. Which Structures and Processes Influence the Prevailing Approaches and Practices?

5. Suggestions

- The nature of citizen participation in relation to democratic legitimacy and accountability, including clarifying why participation is needed (which type of legitimacy);

- The appropriate target groups;

- How and to what extent citizen engagement should be facilitated, and by whom;

- The appropriate time horizon;

- The roles that citizens and authorities should play in different planning stages, to provide a dynamic intermingling of ideas and sharing of understanding between authorities and citizens.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Russo, F.; Rindone, C.; Panuccio, P. The process of smart city definition at an EU level. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2014, 191, 979–989. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Leading the Way in Making Europe’s Cities Smarter—Frequently Asked Questions. 26.11 ed.; European Commission. 2013. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/leading-way-making-europes-cities-smarter---frequently-asked-questions (accessed on 18 April 2020).

- European Commission. Horizon 2020 - Work Programme 2018-2020; Secure, Clean and Efficient Energy 25.03 ed.; European Commission. 2020, pp. 1–318. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/data/ref/h2020/wp/2018-2020/main/h2020-wp1820-energy_en.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2020).

- +CityxChange. What Is a Smart City? +CityxChange. 2019. Available online: https://cityxchange.eu/ (accessed on 18 April 2020).

- Giffinger, R.; Fertner, C.; Kramar, H.; Meijers, E. City-ranking of European medium-sized cities. Cent. Reg. Sci. Vienna UT 2007, 1–12. Available online: http://www.smartcity-ranking.eu/download/city_ranking_final.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2020).

- Schaffers, H.; Komninos, N.; Pallot, M.; Trousse, B.; Nilsson, M.; Oliveira, A. Smart cities and the future internet: Towards cooperation frameworks for open innovation. In The Future Internet Assembly; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 431–446. [Google Scholar]

- Komninos, N.; Pallot, M.; Schaffers, H. Special issue on smart cities and the future internet in Europe. J. Knowl. Econ. 2013, 4, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, A. Against the Smart City: A Pamphlet. This Is Part I of “The City Is Here to Use”; Do projects: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cardullo, P.; Kitchin, R. Being a ‘citizen’ in the smart city: Up and down the scaffold of smart citizen participation in Dublin, Ireland. GeoJournal 2019, 84, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joss, S.; Cook, M.; Dayot, Y. Smart cities: Towards a new citizenship regime? A discourse analysis of the British smart city standard. J. Urban Technol. 2017, 24, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pimbert, M.; Wakeford, T. Deliberative Democracy and Citizen Empowerment; PLA Notes; International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED): London, UK, 2001; pp. 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, T.; Pardo, T.A. Smart city as urban innovation: Focusing on management, policy, and context. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, Tallinn, Estonia, 26–28 October 2011; pp. 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burby, R.J. Making plans that matter: Citizen involvement and government action. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2003, 69, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Herzele, A. Local knowledge in action: Valuing nonprofessional reasoning in the planning process. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2004, 24, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brabham, D.C. Crowdsourcing the public participation process for planning projects. Plan. Theory 2009, 8, 242–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaj Alenka, T.; Roumboutsos, A.; Verlič, P.; Grum, B. Land value capture strategies in PPP—What can FM learn from it? Facilities 2018, 36, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halachmi, A.; Holzer, M. Citizen participation and performance measurement: Operationalizing democracy through better accountability. Public Adm. Q. 2010, 34, 378–399. [Google Scholar]

- Willems, J.; Van den Bergh, J.; Viaene, S. Smart City Projects and Citizen Participation: The Case of London. In Public Sector Management in a Globalized World; Andeßner, R., Greiling, D., Vogel, R., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017; pp. 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, B.F.; Baer, D.; Lindkvist, C. Identifying and supporting exploratory and exploitative models of innovation in municipal urban planning; key challenges from seven Norwegian energy ambitious neighborhood pilots. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 142, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, D. Citizen participation in the planning process: An essentially contested concept? J. Plan. Lit. 1997, 11, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, D.H. Co-creation in urban governance: From inclusion to innovation. Scand. J. Public Adm. 2018, 22, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Floridia, A. From Participation to Deliberation: A Critical Genealogy of Deliberative Democracy; ECPR Press: Colchester, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Scharpf, F.W. Governing in Europe: Effective and Democratic? Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, V.A. Democracy and legitimacy in the European Union revisited: Input, output and ‘throughput’. Political Stud. 2013, 61, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Falleth, E.I.; Hanssen, G.S.; Saglie, I.L. Challenges to democracy in market-oriented urban planning in Norway. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2010, 18, 737–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Halpin, D.R. The participatory and democratic potential and practice of interest groups: Between solidarity and representation. Public Adm. 2006, 84, 919–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, S.P. Public Management: Policy Making, Ethics and Accountability in Public Management; Taylor & Francis: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2002; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Wagle, U. The policy science of democracy: The issues of methodology and citizen participation. Policy Sci. 2000, 33, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, E. The cultures of science and policy. In Policy Analysis: Perspectives, Concepts, and Methods; Dunn, W.N., Ed.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1986; pp. 93–110. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, A.; Ingram, H. Social Construction of Target Populations: Implications for Politics and Policy. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1993, 87, 334–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.L.; Ingram, H.; DeLeon, P. Democratic policy design: Social construction of target populations. Theor. Policy Process 2014, 3, 105–149. [Google Scholar]

- Boedeltje, M.M.; Cornips, J.J. Input and Output Legitimacy in Interactive Governance; NIG Annual Work Conference 2004 Rotterdam. 2004. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1765/1750 (accessed on 18 April 2020).

- Dahl, R.A. On political Equality; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA; London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Innes, J.E.; Booher, D.E. Planning with Complexity: An Introduction to Collaborative Rationality for Public Policy; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Perrow, C. Complex Organizations: A Critical Essay; Scott, Foresman: Glenview, IL, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Nyseth, T. Network governance in contested urban landscapes. Plan. Theory Pract. 2008, 9, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. In The City Reader; LeGates, R.T., Stout, F., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1996; pp. 238–251. [Google Scholar]

- Refstie, H.; Brun, C. Voicing noise: Political agency and the trialectics of participation in urban Malawi. Geoforum 2016, 74, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poulsen, B. Competing traditions of governance and dilemmas of administrative accountability: The case of Denmark. Public Adm. 2009, 87, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetano, A.; Royo, S.; Acerete, B. What is driving the increasing presence of citizen participation initiatives? Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2010, 28, 783–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lindblom, C.E.; Woodhouse, E.J. The Policy-Making Process, 3rd ed.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Potts, R.; Vella, K.; Dale, A.; Sipe, N. Exploring the usefulness of structural–functional approaches to analyse governance of planning systems. Plan. Theory 2014, 15, 162–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gohari, S. Governance in the Planning and Decision-Making Process: The Co-Location Case of University Campuses in Trondheim, Norway [2000-2013]; Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Faculty of Architecture and Design, Department of Architecture and Planning: Trondheim, Norway, 2019; Volume 74. [Google Scholar]

- Forester, J. Planning in the Face of Power; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1989; Available online: https://0-www-tandfonline-com.brum.beds.ac.uk/doi/abs/10.1080/01944368208976167 (accessed on 18 April 2020).

- Dente, B. Who Decides? Actors and Their Resources. In Understanding Policy Decisions; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 29–66. [Google Scholar]

- Fiskaa, H. Past and future for public participation in Norwegian physical planning. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2005, 13, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative, 3rd ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, W.J. An Analysis of Thinking and Research about Qualitative Methods; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Applications of Case Study Research; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012; p. XXXI. [Google Scholar]

- Gbikpi, B.; Grote, J.R. From democratic government to participatory governance. In Participatory Governance; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2002; pp. 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Commission, E. Horizon 2020 Work Programme 2016–2017. Cross-Cutting Activities (Focus Areas) European Commission. 2016. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/data/ref/h2020/wp/2016_2017/ (accessed on 18 April 2020).

- +CityxChange. Team. +CityxChange. 2019. Available online: https://cityxchange.eu/team/ (accessed on 18 April 2020).

- +CityxChange. Objectives. +CityxChange. 2019. Available online: https://cityxchange.eu/objectives/ (accessed on 18 April 2020).

- Kemmis, S.; McTaggart, R.; Nixon, R. Introducing critical participatory action research. In The Action Research Planner; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd, S.A.; Kral, M.J. Practicing participatory action research. J. Couns. Psychol. 2005, 52, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denscombe, M. The Good Research Guide: For Small-scale Social Research Projects; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Trochim, W.M.K. Qualitative measures. Res. Meas. Knowl. Base 2006, 361–9433. [Google Scholar]

- Radu, V. Qualitative Research: Definition, Methodology, Limitation, Examples. 03.04 ed. 2019. Available online: https://www.omniconvert.com/blog/qualitative-research-definition-methodology-limitation-examples.html (accessed on 18 April 2020).

- Trevino, L.K. Ethical Decision Making in Organizations: A Person-Situation Interactionist Model. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardullo, P.; Kitchin, R. Smart urbanism and smart citizenship: The neoliberal logic of ‘citizen-focused’smart cities in Europe. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2019, 37, 813–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- King, L.A. Deliberation, legitimacy, and multilateral democracy. Governance 2003, 16, 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelino, F.; Wittmayer, J.M. Shifting power relations in sustainability transitions: A multi-actor perspective. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2016, 18, 628–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, J.; Whyte, W. How Do You Know If the Informant is Telling the Truth? Hum. Organ. 1958, 17, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bifulco, F.; Tregua, M.; Amitrano, C.C. Co-governing smart cities through living labs. Top evidences from EU. Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2017, 13, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gohari, S.; Ahlers, D.; Nielsen, B.F.; Junker, E. The Governance Approach of Smart City Initiatives. Evidence from Trondheim, Bergen, and Bodø. Infrastructures 2020, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Form and Level of Participation | Role | Citizen Involvement | Political Discourse/Framing | Modality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citizen power | Citizen control | Leader, member | Ideas, vision, leadership, ownership, create | Rights, social/political citizenship, commons | Inclusive, bottom-up, collective, autonomy, experimental |

| Delegated power | Decision-maker, maker | ||||

| Partnership | Co-creator | Negotiate, produce | Participation, co-creation | ||

| Tokenism | Placation (I2) | Proposer | Suggest | Top-down, civic paternalism, stewardship, bound-to-succeed | |

| Consultation | Participant, tester, player | Feedback | Civic engagement | ||

| Information | Recipient | Browse, consume, act | |||

| Consumerism | Choice | Resident, consumer | Capitalism, Market | ||

| Non-participation | Therapy | Patient, learner, user, product, data-point | Steered, nudged, controlled | Stewardship. Technocracy, paternalism | |

| Manipulation | |||||

| Number | Institution | Background |

|---|---|---|

| Interviewee 1 (I1) | Trondheim Municipality/Environmental Unit | Energy and Climate |

| Interviewee 2 (I2) | Trondheim Municipality/CEO | Leadership |

| Interviewee 3 (I3) | Trondheim Municipality/Urban Planning Unit | Architecture |

| Interviewee 4 (I4) | NTNU/Project Administration | Information Technology (IT) |

| Interviewee 5 (I5) | NTNU/Project Administration | Urban Planning |

| Interviewee 6 (I6) | Electricity company (private sector) | Energy |

| Interviewee 7 (I7) | Real Estate company (private sector) | Economy |

| Interviewee 8 (I8) | Citizen, lives in one of the demonstration areas | Female, Middle age |

| Interviewee 9 (I9) | Citizen, lives in one of the demonstration areas | Male, Middle age |

| Interviewee 10 (I10) | Citizen, lives in one of the demonstration areas | Male, Young adult |

| Trondheim Municipality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 quotation: | “Reducing the gap between citizens and the decision-maker authorities. Developing an overarching framework for citizen participation, based on experiences gained within +CityxChange”. | |||

| Interpretation of key theme | Participatory democracy | Deliberative democracy (for people) | Codes that represent scaffolds of smart city participation (Table 1) | |

| By people (voice) | Of people (vote) | |||

| Delegate power and employ their experiences | Develop a citizen-centric framework | Delegated power and partnership. Citizens are decision-makers, ownership, commons, collective | ||

| I2 quotation: | “+CityxChange will find out what citizens’ interest and needs are. If the decision related to citizens’ needs, citizens will be the jury and have power to decide the outcomes. To satisfy the end-user demand and develop good physical environments”. | |||

| Interpretation of key theme | Participatory democracy | Deliberative democracy (for people) | Codes that represent scaffolds of smart city participation (Table 1) | |

| By people (voice) | Of people (vote) | |||

| Empower citizens and employ their interests | Develop a good city | Delegated power and placation. Citizens are proposer and decision-maker but also recipient and consumer. Rights. Hybrid modality (bottom-up and top-down) | ||

| I3 quotation: | “Citizens would be engaged as one of the important stakeholders, solution providers and co-creators of the outcomes related to their needs. To provide real opportunities for citizens to effectively influence the planning processes”. | |||

| Interpretation of key theme | Participatory democracy | Deliberative democracy (for people) | Codes that represent scaffolds of smart city participation (Table 1) | |

| By people (voice) | Of people (vote) | |||

| Empower citizens | Provide real participation opportunities | Partnership, placation and consultation. Citizens are co-creators and proposers, | ||

| NTNU | ||||

| 14 quotation: | “Engage stakeholders and citizens into the project to provide them a platform, in which they can help each other to upgrading their old buildings since they do not have enough money to build new positive energy building alone”. | |||

| Interpretation of key theme | Participatory democracy | Deliberative democracy (for people) | Codes that represent scaffolds of smart city participation (Table 1) | |

| By people (voice) | Of people (vote) | |||

| Inform and educate people. Get feedback | Co-creation. Create PED | Consultation and information. They are recipient, tester, and proposer. Civic paternalism, stewardship, bound-to-succeed | ||

| I5 quotation: | “Engaging people to be informed about the +CityxChange project and to co-create things with them so they could come up with better and interesting additional solutions. Engaging citizens in developing solution for creating PEDs and make the solutions visible for them”. | |||

| Interpretation of key theme | Participatory democracy | Deliberative democracy (for people) | Codes that represent scaffolds of smart city participation (Table 1) | |

| By people (voice) | Of people (vote) | |||

| Inform people and employ their insight and feedback | Create PED. Transparency and clarity | Consultation and information. They are recipient, tester and proposer. Civic paternalism, stewardship, bound-to-succeed | ||

| Private Sector | ||||

| I6 quotation: | “To provide good mobility solutions with regard to user demand”. | |||

| Interpretation of key theme | Participatory democracy | Deliberative democracy (for people) | Codes that represent scaffolds of smart city participation (Table 1) | |

| By people (voice) | Of people (vote) | |||

| Employ people’s interests and demands | Provide good solution | Consultation and information/non-participation. They are recipient, tester and proposer. Paternalism, stewardship, bound-to-succeed | ||

| I7 quotation: | “To change end-user’s behavior to reduce peak load on the grid; knowledge about end-user’s electricity behavior, adaptation of pricing system”. | |||

| Interpretation of key theme | Participatory democracy | Deliberative democracy (for people) | Codes that represent scaffolds of smart city participation (Table 1) | |

| By people (voice) | Of people (vote) | |||

| Educate people | Reduce energy and provide good solution | Non-participation and consumerism. Citizens are consumers and users. Paternalism, stewardship, bound-to-succeed | ||

| Citizens | ||||

| I8 quotation: | “Citizens are the end user of the city. Municipality needs to facilitate their needs. Citizens are Municipality’s partner who has an important role to give input or suggestions from their knowledge to the Municipality. It is better to include the citizens in the early stage of the planning. Because every citizen has different knowledge of their living area”. | |||

| Interpretation of key theme | Participatory democracy | Deliberative democracy (for people) | Codes that represent scaffolds of smart city participation (Table 1) | |

| By people (voice) | Of people (vote) | |||

| Include citizens in decision-making | Better result | Delegate power and partnership. Ideas/vision/inclusive modality | ||

| I9 quotations: | “It’s better that the municipality partners with citizens. Municipality should actively inform citizens about the projects before making any decision”. “Citizens advisory board (like reference group) is one of the good ways to reach citizens”. | |||

| Interpretation of key theme | Participatory democracy | Deliberative democracy (for people) | Codes that represent scaffolds of smart city participation (Table 1) | |

| By people (voice) | Of people (vote) | |||

| Involve, consult, inform, and empower citizens | Citizens advisory board | Better decision-making | Partnership and placation. Ownership. Inclusive modality | |

| I10 quotation: | “We don’t have role as decision maker, it is still municipality and the political party who have rights to make decisions. However, politicians are quite weak when it comes to developers’ interest”. | |||

| Interpretation of key theme | Participatory democracy | Deliberative democracy (for people) | Codes that represent scaffolds of smart city participation (Table 1) | |

| By people (voice) | Of people (vote) | |||

| Delegate power | Empower politicians | Delegate power. Autonomy and collective modality | ||

| Research Questions | Answers | |

|---|---|---|

| What are the prevailing approaches, understandings, and practices in relation to citizen participation amongst the key actors involved in +CityxChange? | Approaches | Practices |

| - Most of the partners at the university and municipality have a complementary approach, aiming not only at giving actual decision-making power to citizens (“by” people), but also at effectiveness of the policy outcomes (“for” the people). - The private sector has been more output-efficiency oriented, aiming at using technology to change behaviors or attitudes of citizens/users, for better unitization of services (“for” people). - The citizens are more mindful about the role and power of their representatives (“of” people). | The prevailing practices are more instrumental and paternalistic rather than normative or political. Additionally, citizens have to perform within the bounds of expected and acceptable behavior, and they cannot transgress or resist any of the project’s social and political norms. Citizens are steered, controlled, and nudged to act in certain ways, being treated as consumers, testers, or sources of data. Therefore, the actors’ practices do not match their approaches and do not go higher than “information” or “consultation” of “tokenism”. | |

| Which structures and processes have influenced the prevailing approaches and practices? | The institutional structure of +CityxChange outside the formal administrative planning, which has resulted in following functional barriers: I. Crossover roles and challenges of representing several interests at the same time; II. Contrasting time horizons; III. Lack of appropriate methodological and ideological framework. | |

| Recommendation | ||

| - Actors need to understand and agree on the nature of the participatory or deliberative democracy, clarifying why participation is needed (which type of legitimacy), who the target groups are, how and to what extent citizen engagement should be facilitated, in which time horizon, and how their own roles fit. - Existence of a dynamic and open platform for intermingling of ideas and sharing of understanding between authorities and citizens. - Benefiting indirect participation through empowerment and formal institutionalization of citizens’ community representatives in urban planning and deliberative governance system. | ||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gohari, S.; Baer, D.; Nielsen, B.F.; Gilcher, E.; Situmorang, W.Z. Prevailing Approaches and Practices of Citizen Participation in Smart City Projects: Lessons from Trondheim, Norway. Infrastructures 2020, 5, 36. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/infrastructures5040036

Gohari S, Baer D, Nielsen BF, Gilcher E, Situmorang WZ. Prevailing Approaches and Practices of Citizen Participation in Smart City Projects: Lessons from Trondheim, Norway. Infrastructures. 2020; 5(4):36. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/infrastructures5040036

Chicago/Turabian StyleGohari, Savis, Daniela Baer, Brita Fladvad Nielsen, Elena Gilcher, and Welfry Zwestin Situmorang. 2020. "Prevailing Approaches and Practices of Citizen Participation in Smart City Projects: Lessons from Trondheim, Norway" Infrastructures 5, no. 4: 36. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/infrastructures5040036