Effect of Broccoli Residue and Wheat Straw Addition on Nitrous Oxide Emissions in Silt Loam Soil

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

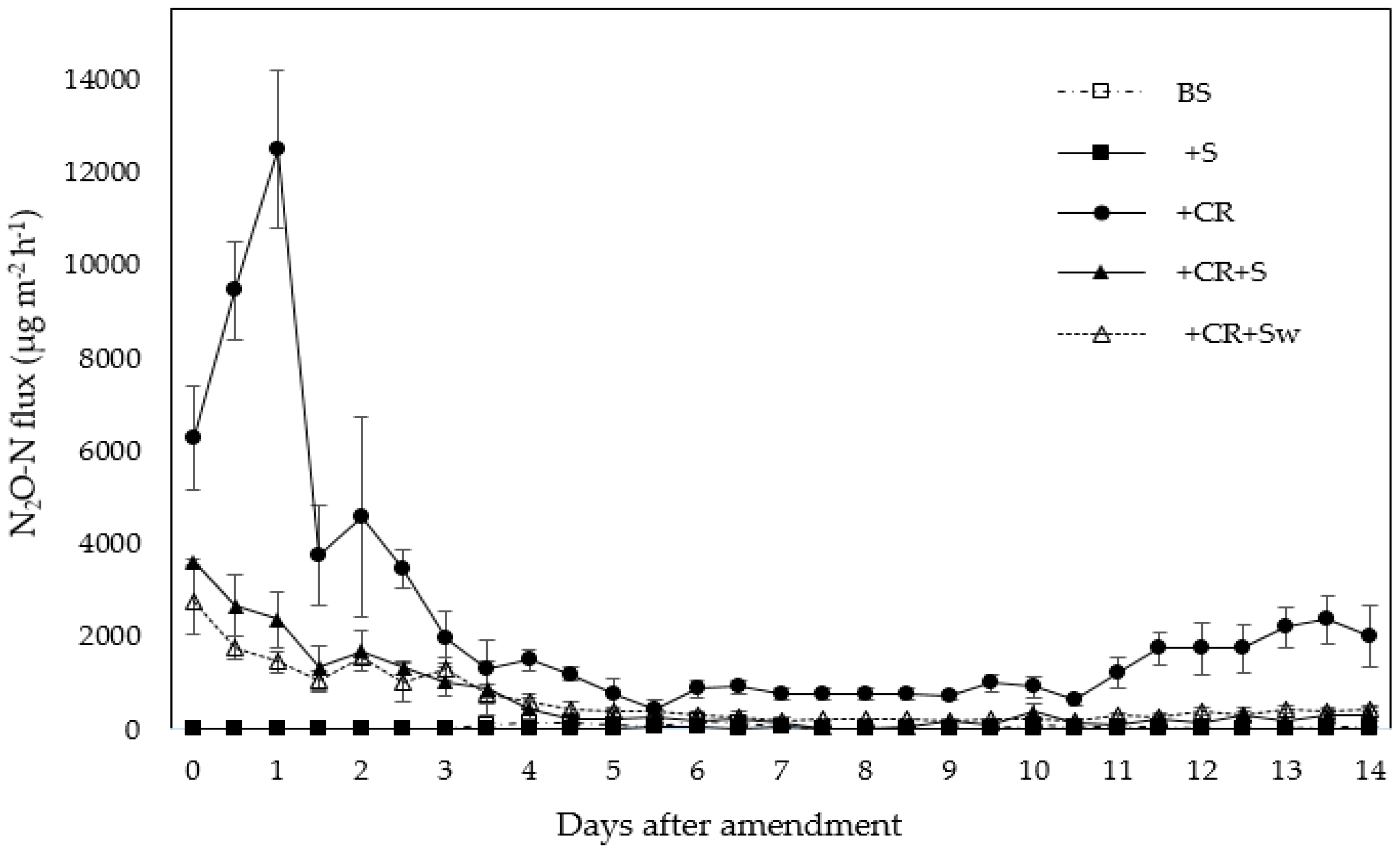

2.1. Nitrous Oxide Emissions

2.2. Carbon Dioxide Emissions

3. Discussion

3.1. Effect of Broccoli Residue on N2O Emissions

3.2. Effect of Straw Addition to Soil

3.3. Effect of Residue Application on CO2 Emissions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Soil

4.2. Broccoli Residue and Straw Preparation

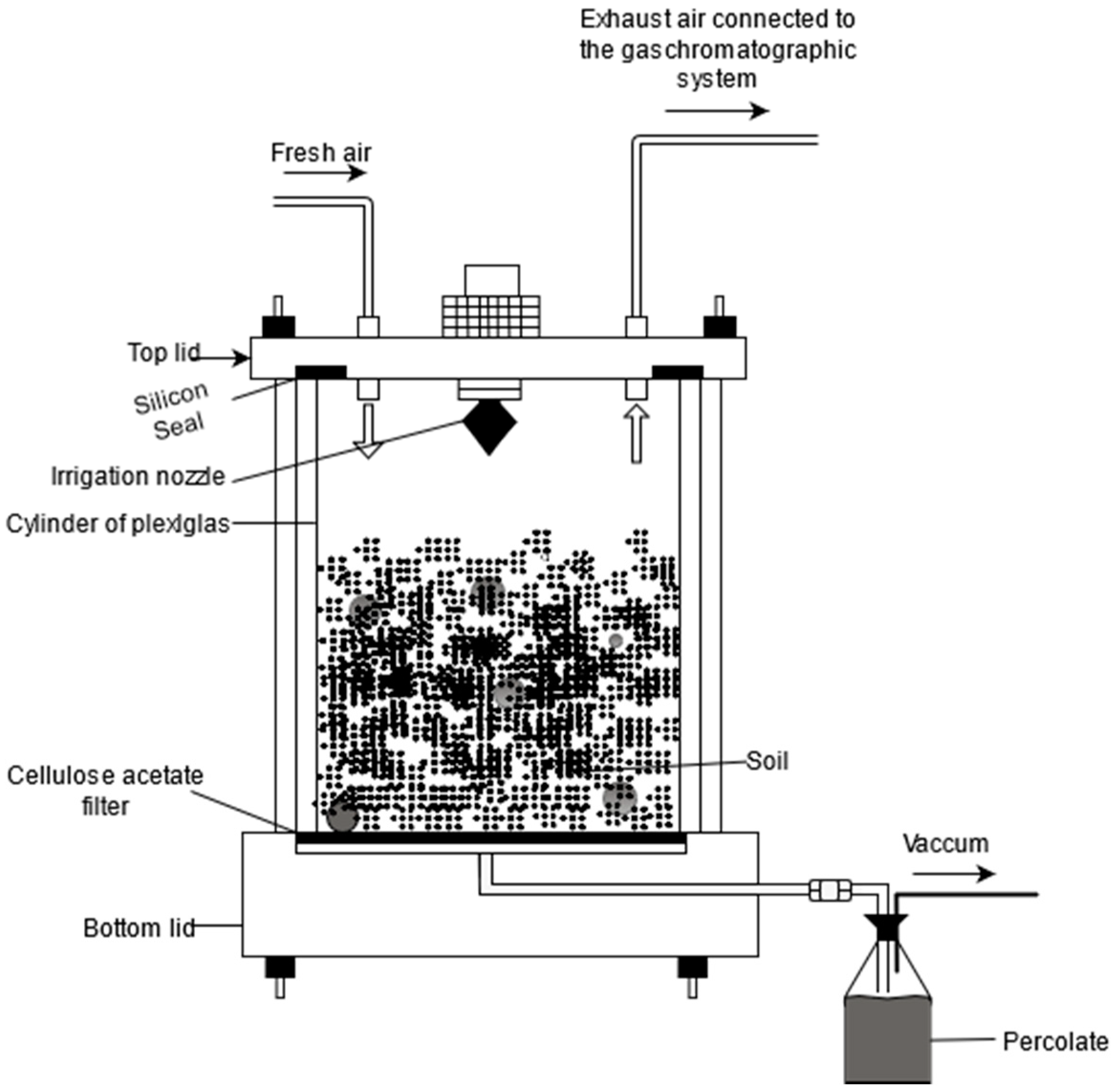

4.3. Soil Microcosm and Experiment Set-Up

4.4. Experimental Design

4.5. Gas Measurement

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Forster, P.; Ramaswamy, V.; Artaxo, P.; Berntsen, T.; Betts, R.; Fahey, D.W.; Nganga, J. Changes in atmospheric constituents and in radiative forcing. In Climate Change 2007; The Physical Science Basis. 2007. Chapter 2; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rodhe, H. A Comparison of the Contribution of Various Gases to the Greenhouse Effect. Science 1990, 248, 1217–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPCC. IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES) for the IPCC: Kanagawa, Japan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mosier, A.; Duxbury, J.; Freney, J.; Heinemeyer, O.; Minami, K. Assessing and Mitigating N2O Emissions from Agricultural Soils. Clim. Chang. 1998, 40, 7–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggs, E.; Rees, R.; Smith, K.; Vinten, A. Nitrous oxide emission from soils after incorporating crop residues. Soil Use Manag. 2006, 16, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feller, C.; Fink, M.; Laber, H.; Maync, A.; Paschold, P.; Scharpf, H.C.; Schlaghecken, J.; Strohmeyer, K.; Weier, U.; Zeigler, J. Dungung im Freilandgemusebau (in German). In Schriftenreihe des Leibniz-Instituts fur Gemuse-und Zierpflanzenbau (IGZ), 3rd ed.; Fink, M., Ed.; Leibniz Institute for Vegetable and Ornamental Plant Cultivation: Grossbeeren, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Everaarts, A.P. General and quantitative aspects of nitrogen fertilizer use in the cultivation of Brassica vegetables. In Workshop on Ecological Aspects of Vegetable Fertilization in Integrated Crop Production in the Field; ISHS: Einsiedeln, Switzerland, 1992; pp. 149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Pfab, H.; Palmer, I.; Buegger, F.; Fiedler, S.; Müller, T.; Ruser, R. Influence of a nitrification inhibitor and of placed N-fertilization on N2O fluxes from a vegetable cropped loamy soil. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2012, 150, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skiba, U.; Smith, K. The control of nitrous oxide emissions from agricultural and natural soils. Chemosphere Glob. Chang. Sci. 2000, 2, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbie, K.E.; Smith, K.A. Nitrous oxide emission factors for agricultural soils in Great Britain: The impact of soil water-filled pore space and other controlling variables. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2003, 9, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, E.G.; Trevors, J.T.; Paul, J.W. Carbon Sources for Bacterial Denitrification. In Advances in Soil Science 12; Metzler, J.B., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 1989; pp. 113–142. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Hu, F.; Shi, W. Plant material addition affects soil nitrous oxide production differently between aerobic and oxygen-limited conditions. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2013, 64, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.D.J.; Harrison, R.; Russell, K.J.; Webb, J. The effect of crop residue incorporation date on soil inorganic nitrogen, nitrate leaching and nitrogen mineralization. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2000, 32, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ruijter, F.; Berge, H.T.; Smit, A. The fate of nitrogen from crop residues of broccoli, leek and sugar beet. Acta Hortic. 2010, 852, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Ruijter, F.J.; Huijsmans, J.F.M.; Rutgers, B. Ammonia volatilization from crop residues and frozen green ma-nure crops. Atmos. Environ. 2010, 44, 3362–3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, I.K.; Hansen, E.M. Cover crop growth and impact on N leaching as affected by pre- and postharvest sowing and time of incorporation. Soil Use Manag. 2013, 30, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, J.N. Effect of catch crops on the content of soil mineral nitrogen before and after winter leaching. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 1992, 155, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aulakh, M.S.; Walters, D.T.; Doran, J.W.; Francis, D.D.; Mosier, A.R. Crop Residue Type and Placement Effects on Denitrification and Mineralization. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1991, 55, 1020–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muhammad, W.; Vaughan, S.M.; Dalal, R.C.; Menzies, N.W. Crop residues and fertilizer nitrogen influence resi-due decomposition and nitrous oxide emission from a Vertisol. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2011, 47, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, J.F.; Papendick, R.I.; Oschwald, W. Factors Affecting the Decomposition of Crop Residues by Microorganisms. Anim. Manure 2015, 101–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiz, P.; Guzman-Bustamante, I.; Schulz, R.; Müller, T.; Ruser, R. Effect of crop residue removal and straw addi-tion on nitrous oxide emissions from a horticulturally used soil in South Germany. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2019, 83, 1399–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, B.; De Neve, S.; Boeckx, P.; Van Cleemput, O.; Hofman, G. Manipulating Nitrogen Release from Nitrogen-Rich Crop Residues using Organic Wastes under Field Conditions. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2007, 71, 1240–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinertsen, S.; Elliott, L.; Cochran, V.; Campbell, G. Role of available carbon and nitrogen in determining the rate of wheat straw decomposition. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1984, 16, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, S.M.; Dalal, R.C.; Harper, S.M.; Menzies, N.W. Effect of fresh green waste and green waste compost on mineral nitrogen, nitrous oxide and carbon dioxide from a Vertisol. Waste Manag. 2011, 31, 1720–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Zou, J.; Zheng, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, X. Nitrous oxide emissions as influenced by amendment of plant residues with different C: N ratios. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2004, 36, 973–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velthof, G.L.; Kuikman, P.J.; Oenema, O. Nitrous oxide emission from soils amended with crop residues. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2002, 62, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groffman, P.M.; Tiedje, J.M. Denitrification in north temperate forest soils: Relationships between denitrification and environmental factors at the landscape scale. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1989, 21, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbie, K.E.; Smith, K.A. The effects of temperature, water-filled pore space and land use on N2O emissions from an imperfectly drained gleysol. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2001, 52, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruser, R.; Flessa, H.; Russow, R.; A Schmidt, G.; Buegger, F.; Munch, J. Emission of N2O, N2 and CO2 from soil fertilized with nitrate: Effect of compaction, soil moisture and rewetting. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2006, 38, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, B.; De Neve, S.; Cabrera, M.D.C.L.; Boeckx, P.; Van Cleemput, O.; Hofman, G. The effect of mixing organ-ic biological waste materials and high-N crop residues on the short-time N2O emission from horticultural soil in model experiments. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2005, 41, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bending, G.D.; Turner, M.K. Turner Interaction of biochemical quality and particle size of crop residues and its effect on the microbial biomass and nitrogen dynamics following incorporation into soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 1999, 29, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parton, W.; Silver, W.L.; Burke, I.C.; Grassens, L.; Harmon, M.E.; Currie, W.S.; King, J.Y.; Adair, E.C.; Brandt, L.A.; Hart, S.C.; et al. Global-Scale Similarities in Nitrogen Release Patterns During Long-Term Decomposition. Science 2007, 315, 361–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Soest, P.J.; Wine, R.H. Determination of Lignin and Cellulose in Acid-Detergent Fiber with Permanganate. J. Assoc. Off. Anal. Chem. 1968, 51, 780–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, C.; Sanchez, P. Nitrogen release from the leaves of some tropical legumes as affected by their lignin and polyphenolic contents. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1991, 23, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanlauwe, B.; Nwoke, O.C.; Sanginga, N.; Merckx, R. Impact of residue quality on the C and N mineralization of leaf and root residues of three agroforestry species. Plant Soil 1996, 183, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahn, C.R.; Lillywhite, R.D. A study of the quality factors affecting the short-term decomposition of field vegetable residues. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2002, 82, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, G.; Liu, J.; Peng, B.; Gao, D.; Wang, C.; Dai, W.; Jiang, P.; Bai, E. Nitrogen, lignin, C/N as important regulators of gross nitrogen release and immobilization during litter decomposition in a temperate forest ecosystem. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 440, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bending, G.D.; Read, D.J. Nitrogen mobilization from protein-polyphenol complex by ericoid and ectomycorrhi-zal fungi. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1996, 28, 1603–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olk, D.C.; Cassman, K.G.; Randall, E.W.; Kinchesh, P.; Sanger, L.J.; Anderson, J.M. Changes in chemical properties of organic matter with intensified rice cropping in tropical lowland soil. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 1996, 47, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajwa, H.A.; Tabatabai, M.A. Decomposition of different organic materials in soils. Biol. Fertil. Soils 1994, 18, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson, D.S. Studies on the decomposition of plant material in soil. v. the effects of plant cover and soil type on the loss of carbon from14c labelled ryegrass decomposing under field conditions. J. Soil Sci. 1977, 28, 424–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmour, J.T.; Clark, M.D.; Sigua, G.C. Estimating Net Nitrogen Mineralization from Carbon Dioxide Evolution. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1985, 49, 1398–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaboneka, S.; Sabbe, W.E.; Mauromoustakos, A. Carbon decomposition kinetics and nitrogen mineralization from corn, soybean, and wheat residues. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 1997, 28, 1359–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Jiménez, E. Nitrogen availability from a mature urban compost determined by the 15N isotope dilution method. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2001, 33, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reber, H.; Schara, A. Degradation sequences in wheat straw extracts inoculated with soil suspensions. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1971, 3, 381–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, B.; Ekbohm, G. Litter mass-loss rates and decomposition patterns in some needle and leaf litter types. Long-term decomposition in a Scots pine forest. VII. Can. J. Bot. 1991, 69, 1449–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | N2O Fluxes, µg N m−2 h−1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 † Day | 1 Day | 3.5 Days | 5.5 Days | |

| Unamended Soil (BS) | 5.1 (0.9) c | 30.2 (20.3) d | 104 (45.3) c | 61.2 (27.4) b |

| Wheat Straw (+S) | 1.8 (1.7) c | 2.5 (2.3) d | 3.9 (2.4) c | 42.1 (13.3) b |

| Broccoli Residue (+CR) | 6277 (1130) a | 12479 (1701) a | 1318 (622) a | 430 (194) a |

| Broccoli Residue + Wheat Straw (+CR+S) | 3606 (48) b | 2370 (612) b | 889 (592) b | 274 (162) a |

| Broccoli Residue+ Washed Wheat Straw(+CR+Sw) | 2772 (722) b | 1450 (231) c | 777 (209) b | 373 (76) a |

| Treatment | Cumulative N2O Emissions, kg N ha−1 | Reduction in N2O Emissions, % |

|---|---|---|

| Unamended Soil (BS) | 0.19 ± 0.08 | - |

| Wheat Straw † (+S) | 0.03 ± 0.02 | 84.0 |

| Broccoli Residue (+CR) | 7.74 ± 0.32 | - |

| Broccoli Residue + Wheat Straw (+CR+S) | 2.07 ± 0.20 | 73.3 |

| Broccoli Residue + Washed Wheat Straw (+CR+Sw) | 2.01 ± 0.16 | 74.2 |

| Residue | DM † (%) | C (% of DM) | N (% of DM) | CN Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broccoli | 14.5 | 41.1 | 5.0 | 8.3 |

| Wheat Straw | 90.0 | 40.0 | 0.5 | 80.0 |

| Washed Straw | 90.0 | 37.6 | 0.1 | 259.3 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Budhathoki, R.; Panday, D.; Seiz, P.; Ruser, R.; Müller, T. Effect of Broccoli Residue and Wheat Straw Addition on Nitrous Oxide Emissions in Silt Loam Soil. Nitrogen 2021, 2, 99-109. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/nitrogen2010007

Budhathoki R, Panday D, Seiz P, Ruser R, Müller T. Effect of Broccoli Residue and Wheat Straw Addition on Nitrous Oxide Emissions in Silt Loam Soil. Nitrogen. 2021; 2(1):99-109. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/nitrogen2010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleBudhathoki, Rajan, Dinesh Panday, Perik Seiz, Reiner Ruser, and Torsten Müller. 2021. "Effect of Broccoli Residue and Wheat Straw Addition on Nitrous Oxide Emissions in Silt Loam Soil" Nitrogen 2, no. 1: 99-109. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/nitrogen2010007