Haitian Archaeological Heritage: Understanding Its Loss and Paths to Future Preservation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background: Archaeological Research in Haiti

3. Note on Method

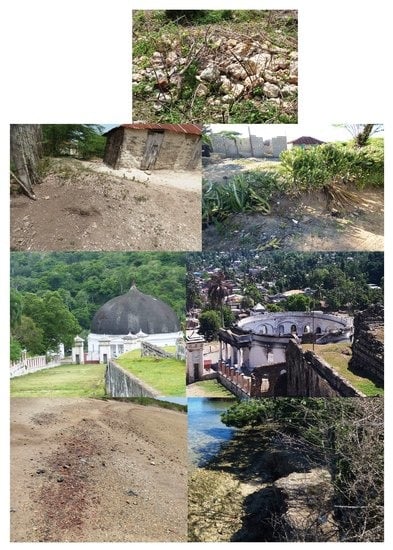

4. Current State of Archaeological Heritage: Northern Haiti

4.1. Fort-Liberté Region

4.2. Puerto Real and En Bas Saline

4.3. World Heritage Site: Parc National Historique

5. Public Institutions and Archaeological Heritage

6. Discussion and Conclusions: Embracing Loss and Planning the Future

6.1. Archaeological Heritage and the Politics of Heritage in Haiti

6.2. “Common Enjoyment” of Heritage

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Babelon, J.-P.; Chastel, A. La Notion de Patrimoine; Payot: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Benhamou, F. Économie du Patrimoine Culturel; La Découverte: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R. Heritage: Critical Approaches; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Poulot, D. Patrimoine et Modernité; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels, K.L. Mobilizing Heritage, Anthropological Practice and Transnational Prospects; University Press of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Di Méo, G. Processus de patrimonialisation et construction des territoires. In Proceedings of the Colloque “Patrimoine et Industrie en Poitou-Charentes: Connaître pour Valoriser”, Poitiers-Châtellerault, France, 12–14 September 2007; Geste Éditions: Poitiers-Châtellerault, France, 2007; pp. 87–109. [Google Scholar]

- Trabelsi, S. Développement Local et Valorisation du Patrimoine Culturel Fragile: Le Rôle Médiateur des ONG: Cas du Sud-Tunisien; Université Nice Sophia Antipolis: Cote d’Azur, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Davallon, J.; Du patrimoine à la patrimonialisation. Lauret, J.-M., Ed.; Available online: http://preac.crdp-paris.fr/fileadmin/user_upload/Ressources/2012/1_Jean_Davallon.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2020).

- Pajard, A.; Ollivier, B. Traces et légitimation du passe: Des objets aux corps. In L’Homme-Trace: Des Traces du Corps au Corps-Trace; Galinon-Melenec, B., Ed.; CNRS Éditions via OpenEdition: Paris, France, 2019; pp. 371–388. [Google Scholar]

- Hofman, C.L.; Haviser, J.B. Managing our Past into the Future: Archaeological Heritage Management in the Dutch Caribbean; Sidestone Press: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, L.-A. Managing built heritage for tourism in Trinidad and Tobago: Challenges and opportunities. J. Herit. Tour. 2013, 8, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, P.E.; Hofman, C.L.; Bérard, B.; Murphy, R.; Hung, J.U.; Rojas, R.V.; White, C. Confronting Caribbean heritage in an archipelago of diversity: Politics, stakeholders, climate change, natural disasters, tourism, and development. J. Field Archaeol. 2013, 38, 376–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, P.E.; Righter, E. Protecting Heritage in the Caribbean; University of Alabama Press: Tuscaloosa, AL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Boger, R.; Perdikaris, S.; Rivera-Collazo, I. Cultural heritage and local ecological knowledge under threat: Two Caribbean examples from Barbuda and Puerto Rico. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2019, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cooper, J.; Peros, M. The archaeology of climate change in the Caribbean. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2010, 37, 1226–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglass, K.; Cooper, J. Archaeology, environmental justice, and climate change on islands of the Caribbean and southwestern Indian Ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 8254–8262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dunnavant, J.P.; Flewellen, A.O.; Jones, A.; Odewale, A.; White, W. Assessing Heritage Resources in St. Croix Post-Hurricanes Irma and Maria. Transform. Anthropol. 2018, 26, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezcurra, P.; Rivera-Collazo, I.C. An assessment of the impacts of climate change on Puerto Rico’s Cultural Heritage with a case study on sea-level rise. J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 32, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, S.M. On the shoals of giants: Natural catastrophes and the overall destruction of the Caribbean’s archaeological record. J. Coast. Conserv. 2012, 16, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, K.A.; Lewis, T.L. Green Gentrification and Disaster Capitalism in Barbuda: Barbuda has long exemplified an alternative to mainstream tourist development in the Caribbean. After Irma and Maria, that could change. NACLA Rep. Am. 2018, 50, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Baird, T.; James, M.; Ram, Y. Climate change and cultural heritage: Conservation and heritage tourism in the Anthropocene. J. Herit. Tour. 2016, 11, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, C.L.; Hoogland, M.L.P. Connecting stakeholders: Collaborative preventive archaeology projects at sites affected by natural and/or human impacts. Caribb. Connect. 2016, 5, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Scantlebury, M. The impact of climate change on heritage tourism in the Caribbean: A case study from Speightstown, Barbados, West Indies. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Impacts Responses 2009, 1, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Simpson, M.C.; Sim, R. The vulnerability of Caribbean coastal tourism to scenarios of climate change related sea level rise. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 883–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancioff, C.E.; Stojanov, R.; Kelman, I.; Němec, D.; Landa, J.; Tichy, R.; Prochazka, D.; Brown, G.; Hofman, C.L. Local perceptions of climate change impacts in St. Kitts (Caribbean sea) and Malé, Maldives (Indian ocean). Atmosphere 2018, 9, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hofman, C.L.; Hung, J.U.; Malatesta, E.H.; Jean, J.S.; Sonnemann, T.; Hoogland, M. Indigenous Caribbean perspectives: Archaeologies and legacies of the first colonised region in the New World. Antiquity 2018, 96, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean, J.S. La Biographie D’un Paysage: Etude sur les Transformations de Longue Durée du Paysage Culturel de la Région de Fort-Liberté, Haïti; Sidestone Press: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Koski-Karell, D. Prehistoric Northem Haïti Settlement in Diacronic Ecological Context. Ph.D. Thesis, Catholic University of America, Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, C.; Tremmel, N. Settlement Patterns in Pre-Columbian Haiti: An Inventory of Archaeological Sites; Bureau National d’Ethnologie: Port-au-Prince, Haiti, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- DeSilvey, C.; Harrison, R. Anticipating loss: Rethinking endangerment in heritage futures. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2020, 26, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Korka, E. The Protection of Archaeological Heritage in Times of Economic Crisis; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, P.G. Empowering Communities through Archaeology and Heritage: The Role of Local Governance in Economic Development; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nijkamp, P. Economic valuation of cultural heritage. In The Economics of Uniqueness: Investing in Historic City Cores and Cultural Heritage Assets for Sustainable Development; Licciardi, G., Amirtahmasebi, R., Eds.; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 75–103. [Google Scholar]

- Throsby, D. Heritage economics: A conceptual framework. In The Economics of Uniqueness: Investing in Historic City Cores and Cultural Heritage Assets for Sustainable Development; Licciardi, G., Amirtahmasebi, R., Eds.; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 45–74. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Burra Charter (Fourth Version): The Australia ICOMOS Charter for the Conservation of Places of Cultural Significance; ICOMOS: Charenton-le-Pont, France, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Poulios, I. Moving Beyond a Values-Based Approach to Heritage Conservation. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2010, 12, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulios, I. The Past in the Present: A Living Heritage Approach—Meteora, Greece; Ubiquity Press: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, I.J.M. Heritage from Below; Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.: Farnham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.; Wobst, H.M. The next step: An archaeology for social justice. In Indigenous Archaeologies: Decolonising Theory and Practice; Smith, C., Wobst, H.M., Eds.; Routledge: Abington, UK, 2004; p. 369. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritage; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Waterton, E. Politics, Policy and the Discourses of Heritage in Britain; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, S.; Waterton, E. Heritage and community engagement. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2010, 16, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, U.Z. Archaeological futures and the postcolonial critique. In Archaeology and the Postcolonial Critique; Leibmann, M., Rizvi, U.Z., Eds.; AltaMira Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 2008; pp. 197–203. [Google Scholar]

- Lenik, S. Community engagement and heritage tourism at Geneva Estate, Dominica. J. Herit. Tour. 2013, 8, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankatsing, N.T.; Hofman, C.L. Engaging Caribbean island communities with indigenous heritage and archaeology research. JCOM J. Sci. Commun. 2018, 17, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vendryes, M.-L. Haiti, Museums and Public Collections: Their History and Development after 1804. In Plantation to Nation: Caribbean Museums and National Identity; Cummins, A., Farmer, K., Russell, R., Galla, A., Eds.; Common Ground: Champaign, IL, USA, 2013; pp. 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell, S. Heritage, memory and identity. In The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity; Graham, B., Howard, P., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing: Farnham, UK, 2016; pp. 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Beauvoir-Dominique, R. Puerto Real: Défis nationaux et internationaux de l’archéologie haïtienne. In Caribbean Archaeology and World Heritage Convention; Sanz, N., Ed.; World Heritage Papers 14; Unesco: Paris, France, 2005; pp. 178–184. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, M. Mise en Scène des Collections Archéologiques en Haïti, Le Cas du Musée du Panthéon National Haïtien et du Musée Ethnographique du Bureau National Ethnologie. Master’s Thesis, Université d’ Etat d’ Haiti, Port-au-Prince, Haiti, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Demesvar, K. Interprétation et Mise en Valeur du Patrimoine Naturel et Culturel, Matériel et Immatériel Dans les Parc Nationaux-Cas du Parc National Historique: Citadelle, Sans-Souci, Ramiers de la République d’Haïti. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Laval, Laval, QC, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Geller, P.L.; Marcelin, L.H. In the shadow of the Citadel: Haitian national patrimony and vernacular concerns. J. Soc. Archaeol. 2020, 20, 49–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dautruche, J.R. Tourisme culturel et patrimoine remodelé: Dynamique de mise en valeur du patrimoine culturel immatériel en Haïti. Ethnologies 2013, 35, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turgeon, L.; Divers, M. Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Rebuilding of Jacmel and Haiti Jakmèl kenbe la, se fòs peyi a!1. Mus. Int. 2010, 62, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorcé, R. Participation communautaire, patrimoine et tourisme en Haïti: Le cas du parc de Martissant. Rabaska Revue d’ethnologie de l’Amérique Française 2019, 17, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Régulus, S. Transmission de la Prêtrise Vodou: Devenir Ougan ou Manbo en Haïti. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Laval, Laval, QC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Augustin, J.R. Mémoire de L’esclavage en Haïti. Entrecroisement des Mémoires et Enjeux de la Patrimonialisation. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Laval, Laval, QC, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Charlevoix, P.-F.-X. Histoire de L’isle Espagnole ou de S. Domingue Écrite Particulièrement sur des Mémoires Manuscrits du P. Jean-Baptiste le Pers, Jésuite, Missionnaire à Saint-Domingue, et sur les Pièces Originales, qui se Conservent au Dépôt de la Marine; Jacques Gérin: Paris, France, 1730; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Delpuech, A. Sur la constitution des Naturels du pays: Archaeology in French Saint-Domingue in the Eighteenth Century. In Proceedings of the 25th International Congress for Caribbean Archaeology, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 15–21 July 2013; pp. 582–607. [Google Scholar]

- Moreau de Saint-Méry, L.-É. Description Topographique, Physique, Civile, Politique et Historique de la Partie Française de L’isle Saint-Domingue; Chez Dupont: Paris, France, 1797; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Alberti Bosch, N. Alfaneria Indigena, Antillas y Centro America, Isla de Haïti o Quisquella; Paufilia: Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Fewkes, J.W. A Prehistoric Island Culture Area of America; US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1922. [Google Scholar]

- Piacentini, R. A propos de fragments de poteries Indiennes. Bull. Seminaire-College St. Martial 1914, 1, 234–239. [Google Scholar]

- Reynoso, A. Notas Acerca del Cultivo en Camellones: Agricultura de los Indígenas de Cuba y Haití; E. Leroux.: Paris, France, 1881. [Google Scholar]

- Safford, W.E. Identity of cohoba, the narcotic snuff of ancient Haiti. J. Wash. Acad. Sci. 1916, 6, 547–562. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, R.L. The Story of Fort Liberty and the Dauphin Plantation; Cavalier Press: Richmond, VA, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, H. Cultural Sequence in Haiti. Exploration and Field-Work of Smithson. Inst. 1931 1932, 3134, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Rainey, F.G. A new prehistoric culture in Haiti. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1936, 22, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boggs, S.H. Note on excavation in northern Haiti. Am. Antiq. 1940, 3, 258. [Google Scholar]

- Rainey, F.G. Excavations in the Ft. Liberté Region., Haiti; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Rouse, I.G. Prehistory in Haiti: A Study in Method; Yale Publications in Anthropology: New Haven, CT, USA, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Rouse, I.G. Culture of Fort Liberte Region., Haiti; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1941; Volume 24. [Google Scholar]

- Charlier-Doucet, R. Anthropologie, politique et engagement social. L’expérience du Bureau d’ethnologie d’Haïti. Gradhiva Rev. D’anthropol. D’hist. Arts 2005, 1, 109–125. [Google Scholar]

- Viré, A. La préhistoire en Haïti. Bull. Soc. Préhist. Fr. 1940, 37, 108–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubourg, M. Les recherches archéologiques de M. Herber Krieger dans le nord d’ Haiti. Bull. Bur. D’Ethnol. 1947, 3, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Aubourg, M. Haiti Prehistorique: Memoire sur les Cultures Précolombiennes Ciboney et Taino; Editions Panorama: Port-au-Prince, Haiti, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, P. Les Cultures Cadet et Manigat, Emplacements de Villages Précolombiens Dans le Nord-Ouest D’ Haiti; Imprimerie de L’Etat: Port-au-Prince, Haiti, 1961; Volume 26, pp. 1–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bastien, R. Archéologie de la Baie de Port-au-Prince. Bull. Bur. D’Ethnol. 1944, 3, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, K. Une tête anthropomorphique en pierre de L’ile a Cabrit. Bull. Bur. D’Ethnol. 1944, 3, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, K. La Culture Préhistorique d’ Haiti (Ciboneys). Bull. Bur. D’Ethnol. Répub. D’Haiti 1947, 2, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Roumain, J. L’outillage lithique des Ciboney d’Haiti. Bull. Bur. D’Ethnol. Répub. D’Haiti 1943, 2, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Roumain, J. Site de Source Matelas-Cabaret. Bull. Bur. D’Ethnol. 1943, 3, 25–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, W. Puerto Real and Limbé: An Analysis; Musée Guahaba: Limbé, Haiti, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, W. Quelques reflexions sur la Roche Tempée. Bull. Bur. Natl. D’Ethnol. 1984, 1, 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, W. The Search for la Navidad, Explorations at En Bas Saline, 1983; Musée Guahaba: Limbé, Haiti, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Davilia, O. Analysis of the Lithic Materials of the Savanne Carré No. 2 Site, Ft. Liberté Region in Haiti. Boletín de Museo del Hombre Dominicana 1978, 7, 201–226. [Google Scholar]

- Keegan, W.F. Archaeological excavations on Ile a Rat, Haiti: Avoid the Oid. In Proceedings of the 18th International Congress for Caribbean Archaeology, St. George, Grenada, 11–17 July; Richard, G., Ed.; Basse-Terre: L’Association Internationale d’Archéologie de la Caraïbe: St. George, Grenada, 2001; pp. 233–239. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, E.; Guerrero, J. El fechado del sito Mellacoide Bois Charite, Haiti. Boletin del Museo del Homre 1982, 17, 29–53. [Google Scholar]

- Rainey, F.G.; Aguilu, O. Bois Noeuf: The Archaeological View from West. Central Haiti; Bureau National D’Ethnologie: Port-au-Prince, Haiti, 1983; p. 89. [Google Scholar]

- Rouse, I. The Olsen collection from Ile a Vache, Haiti. Fla. Anthropol. 1982, 35, 169–185. [Google Scholar]

- Rouse, I.; Moore, C. Cultural sequence in southwestern Haiti. Bull. Bur. Natl. D’Ethnol. 1984, 1, 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Jagou, S. Cinq ans d’explorations en Haïti. Spelunca 2014, 136, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kambesis, P.N.; Lace, M.J.; Despain, J.; Goodbar, J. Assessment of Grotte Marie-Jeanne, Port-à-Piment, Republique D’Haiti; Delivered to Ministère du Tourisme: Port-au-Prince, Haïti, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lace, M.J. Advances in the Exploration and Management of Coastal Karst in the Caribbean. In Environmental Management and Governance: Advances in Coastal and Marin; Finkl, C.W., Makowski, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland; New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 143–172. [Google Scholar]

- Testa, O.; Devillers, C. Expédition Spéléologique en Haïti Ayiti Toma. 2009. Available online: https://rapports-expeditions.ffspeleo.fr/2009-023.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2020).

- Beauvoir-Dominique, R. Rock Art of Haiti. In Rock Art of Latin America and the Caribbean: Thematic Studies; ICOMOS, Ed.; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2006; pp. 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Beauvoir-Dominique, R. The rock images of Haití. A living heritage. In Rock Art of the Caribbean; Hayward, M., Atkinson, L.G., Cinquino, M.A., Eds.; University of Alabama Press: Tuscaloosa, AL, USA, 2009; pp. 78–89. [Google Scholar]

- Salgado, A. Hauts-Lieux Sacrés Dans le Sous-Sol D’Haïti; Ateliers Fardin: Port-au-Prince, Haïti, 1980; p. 243. [Google Scholar]

- Deagan, K. Initial encounters: Arawak responses to European contact at the En Bas Saline site, Haiti. In Proceedings of the First San Salvador Conference, San Salvador, The Bahamas, 3 October–5 November 1986; Gerace, D.T., Ed.; College Center of the Finger Lakes: San Salvador, The Bahamas, 1987; pp. 341–359. [Google Scholar]

- Deagan, K. A la recherche de la Nativité. Bull. Natl. D’Ethnol. 1992, 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Ewen, C.R. From Spaniard to Creole: The Archaeology of Cultural Formation at Puerto Real, Haiti; University of Alabama Press: Tuscaloosa, AL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fairbanks, C.; Marrinan, R. The Puerto Real Project, Haiti. In Proceedings of the 9th International Congress for the Study of Precolumbian Cultures of the Lesser Antilles, Santo-Domingo, Dominican Republic, 2–8 August 1981; Centre de Recherches Caraïbes, Université de Montréal: Montréal, Canana, 1983; pp. 409–417. [Google Scholar]

- LeFebvre, M.J. Animals, Food, and Social Life Among the Pre-Columbian Taino of En Bas Saline, Hispaniola. PhD. Thesis, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McEwan, B.G. Domestic Adaptation at Puerto Real, Haiti. Hist. Archaeol. 1986, 20, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitz, E.J. Vertebrate Fauna from Locus 39, Puerto Real, Haiti. J. Field Archaeol. 1986, 13, 317–328. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, G. A soil resistivity survey of 16th century Puerto Real, Haiti. J. Field Archaeol. 1984, 11, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M. Sub-surface patterning at 16th century Spanish Puerto Real, Haiti. J. Field Archaeol. 1986, 13, 283–296. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, R. Empire and Architecture at 16th Century Puerto Real, Hispaniola. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Deagan, K. Puerto Real: The Archaeology of a Sixteenth Century Spanish Town in Hispaniola; University Press of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Le Bulletin de l’Ipan. Available online: Ispan.gouv.ht:https://ispan.gouv.ht/?page_id=442 (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Cauna, J. Patrimoine et mémoire de l’esclavage en Haïti: Les vestiges de la société d’habitation coloniale. In Situ 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lerebours, M.P. L’habitation Sucrière Dominguoise et Vestiges D’habitations Sucrières Dans la Région de Port.-au-Prince; Éditions Presses Nationales Haïti: Port-au-Prince, Haiti, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe, J.C. New Light from Haiti’s Royal Past Recent Archaeological Excavations in the Palace of Sans-Souci, Milot. J. Haitian Stud. 2017, 23, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnemann, T.; Jean, J.S. Living on Heritage—Amerindian Presence in Haiti. (Video). 2016. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X-VIK6oLewk&t=7s (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Guzman, J. Environmental Impact Assessment, SISALCO 4.000 ha Pilot Sisal Plantation Project in North-East Haiti; Ministry of Agriculture, Natural Resources, and Rural Development: Port-au-Prince, Haiti; Inter American Development Bank: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–218. [Google Scholar]

- Voltaire, L. Etude D’impact Social du Projet Proposé de Développement du Sisal Dans la Région Nord-Est D’Haïti; Delivered to Ministère de L’Agriculture, des Ressources Naturelles et du Développement Rural (MARNDR): Port-au-Prince, Haiti, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ménanteau, L.; Vanney, J.-R. Atlas Côtier du Nord-Est D’Haïti: Environment et Patrimoine Culturel de la Région de Fort-Liberté; Ministère de la Culture: Port-au-Prince, Haiti, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ceci.ca.fr. Available online: https://ceci.ca/fr/nouvelles-evenements/rapport-dinventaire-des-ressources-touristiques-du-nord-et-du-nord-est-projet-dappui-au-developpement-touristique-de-la-region-nord-dhaiti (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Beauvoir-Dominique, R. Puerto-Real: Pour une Mise en Valeur Nationale, Caraïbéenne et Mondiale; Projet Route 2004: Port-au-Prince, Haiti, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- ISPAN. Le Parc National Historique Citadelle, Sans-Souci, Ramiers: Etat de Conservation; Institut de Sauvegarde du Patrimoine National: Port-au-Prince, Haïti, 2010; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Loi 27 Juillet 1927. Règlementant le service domanial. In Bulletin des lois et actes 1927; Edition officielle (Ed.) Imprimerie de l’Etat: Port-au-Prince, Haïti, 1928; pp. 183–189. [Google Scholar]

- ISPAN. Lois, décrets et sauvegarde du patrimoine. Bulletin de de l’Ispan 2011, 27, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Le Moniteur. Loi 1940 classant comme monuments historiques les immeubles dont la conservation présente un intérêt public. Le Moniteur. Journal Officiel de la République d’Haiti 1940, 34, 268–272.

- Le Moniteur. Décret-loi du 31 octobre 1941. La Création du Bureau d’Ethnologie. Le Moniteur. Journal Officiel de la Républiqued’Haiti 1941, 94, 770–771.

- Le Moniteur. Decret du 5 avril 1979. L’Institut de Sauvegarde du Patrimoine National (ISPAN). Le Moniteur. Journal Officiel de la République d’Haiti 1979, 32, 81–82.

- Le Moniteur. Jeudi 21 octobre 1982. Création du Musée du Panthéon National haïtien (MUPANAH). Le Moniteur. Journal Officiel de la République d’Haiti 1982, 73, 63–67.

- ISPAN. 200 Monuments et Sites D’Haïti a Haute Valeur Culturelle, Historique ou Architecturale; Henri Deschamps: Port-au-Prince, Haiti, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rocourt, M. La Citadelle Henry; Global Project Service Inc.: Quoquina, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Le Moniteur. Décret du 10 mai 1989. La Commission Nationale du Patrimoine. Le Moniteur. Journal. Officiel de la Républiqued’Haiti 1989, 55, 956–960.

- Icom. Available online: https://icom.museum/en/ressource/emergency-red-list-of-haitian-cultural-objects-at-risk/ (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Stolk, D. Contributing to Haiti’s Recovery through Cultural Emergency Response. Mus. Int. 2010, 62, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, A. First Aid for Haiti’s Cultural Heritage. Mus. Int. 2010, 62, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, W. Haiti: Threatened Cultural Heritage and New Opportunities. Mus. Int. 2010, 62, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elie, D. The Role of ISPAN in the Restoration of Memory. Mus. Int. 2010, 62, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, O.J. Port-au-Prince: Historical Memory as a Fundamental Parameter in Town Planning. Mus. Int. 2010, 62, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MCC. Actes des Assises Nationales de la Culture; Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication (MCC): Port-au-Prince, Haiti, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vendryes, M.-L. Des fragments et des traces. Lett. L’OCIM 2003, 88, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Trouillot, M.-R. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Pesoutova, J. Indigenous Ancestors and Healing Landscapes: Cultural Memory and Intercultural Communication in the Dominican Republic and Cuba; Sidstone Press: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pesoutova, J. Paisajes curativos dominicanos como expresión de la memoria cultural: Una reflexión sobre sus rizomas. Cienc. Soc. 2019, 44, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Tennant, E. The “Color” of Heritage: Decolonizing Collaborative Archaeology in the Caribbean. J. Afr. Diaspora Archaeol. Herit. 2014, 3, 26–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, J. Les enjeux de la patrimonialisation du parc historique de la canne-à-sucre en Haïti. Articulo-J. Urban Res. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jean, J.S.; Joseph, M.; Louis, C.; Michel, J. Haitian Archaeological Heritage: Understanding Its Loss and Paths to Future Preservation. Heritage 2020, 3, 733-752. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/heritage3030041

Jean JS, Joseph M, Louis C, Michel J. Haitian Archaeological Heritage: Understanding Its Loss and Paths to Future Preservation. Heritage. 2020; 3(3):733-752. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/heritage3030041

Chicago/Turabian StyleJean, Joseph Sony, Marc Joseph, Camille Louis, and Jerry Michel. 2020. "Haitian Archaeological Heritage: Understanding Its Loss and Paths to Future Preservation" Heritage 3, no. 3: 733-752. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/heritage3030041