A Review of the Synthetic Strategies toward Dihydropyrrolo[1,2-a]Pyrazinones

Abstract

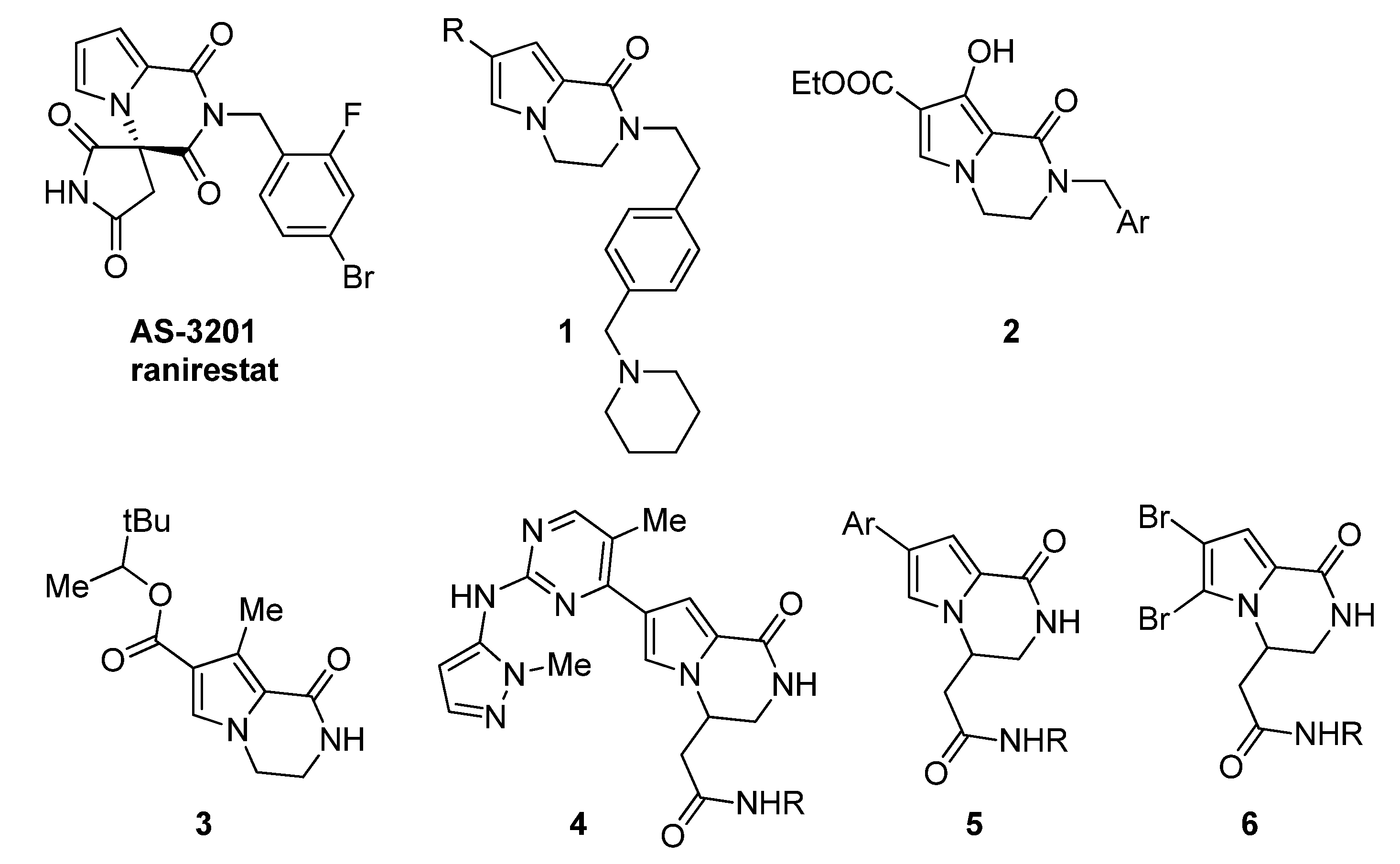

:1. Introduction

2. Fusion of a Pyrazinone to a Pyrrole Derivative

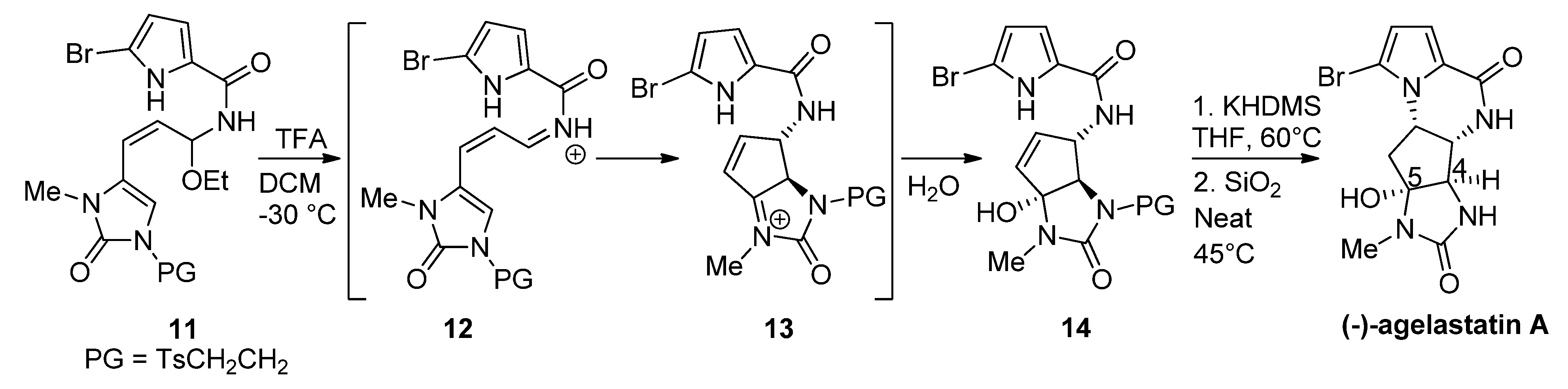

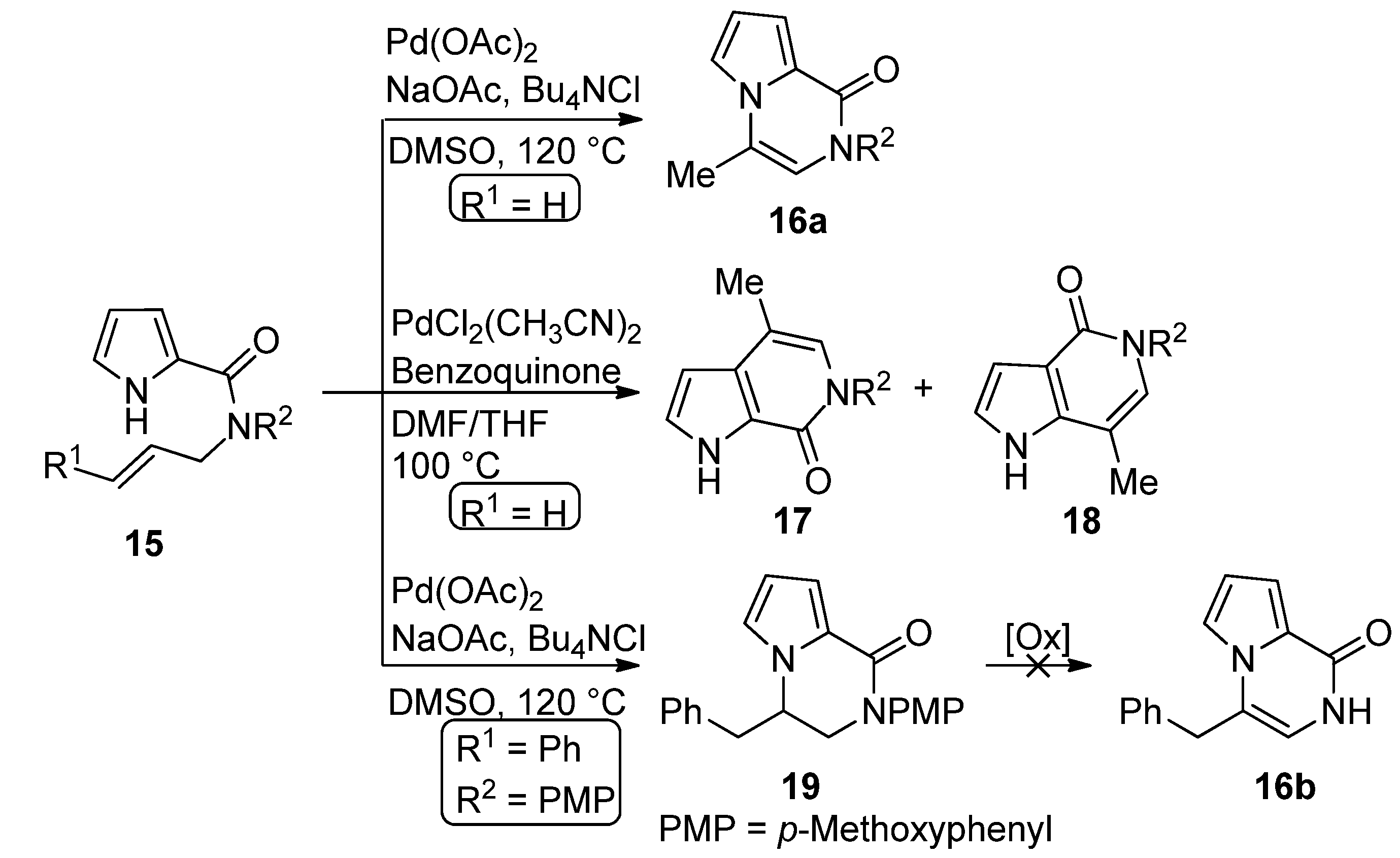

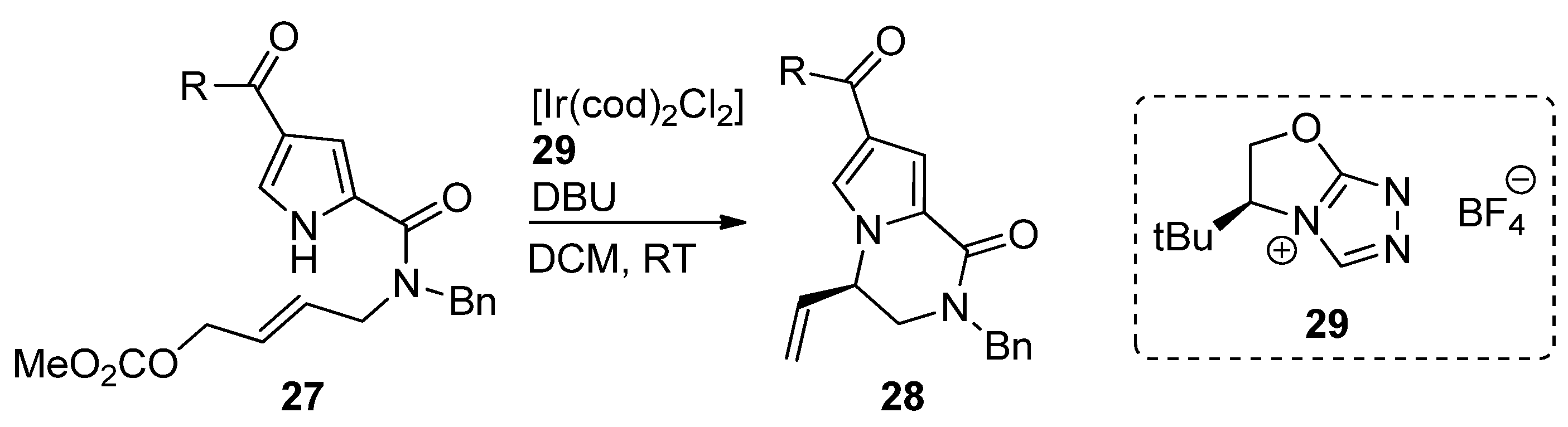

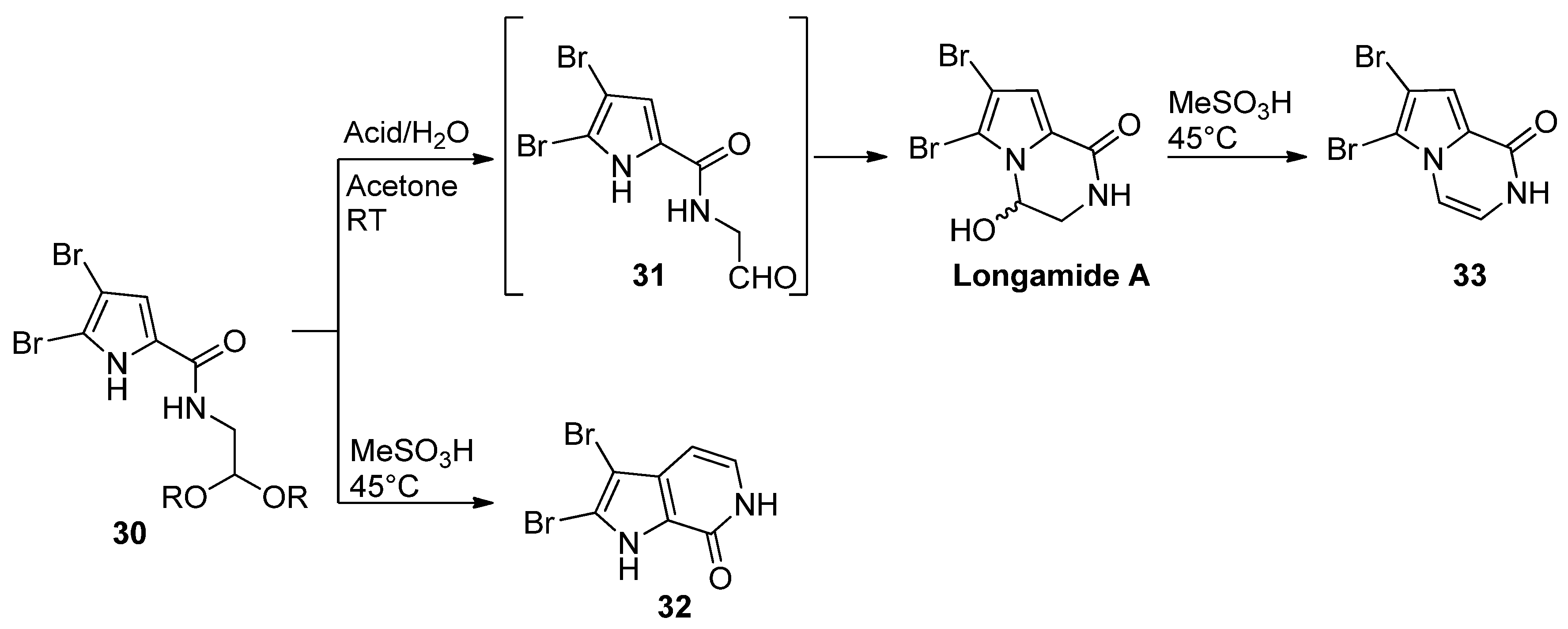

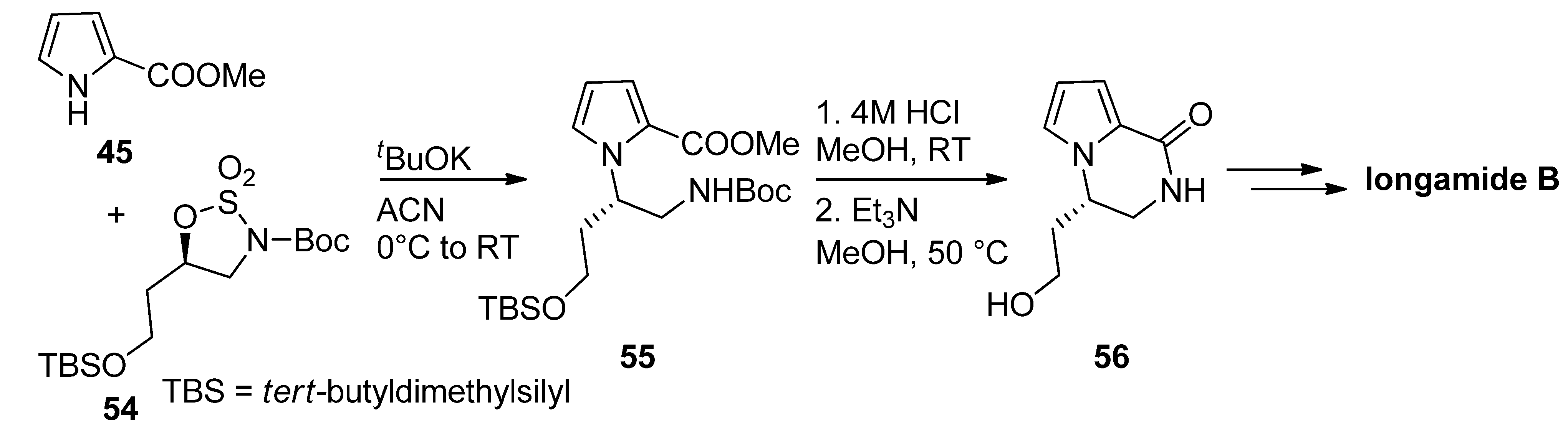

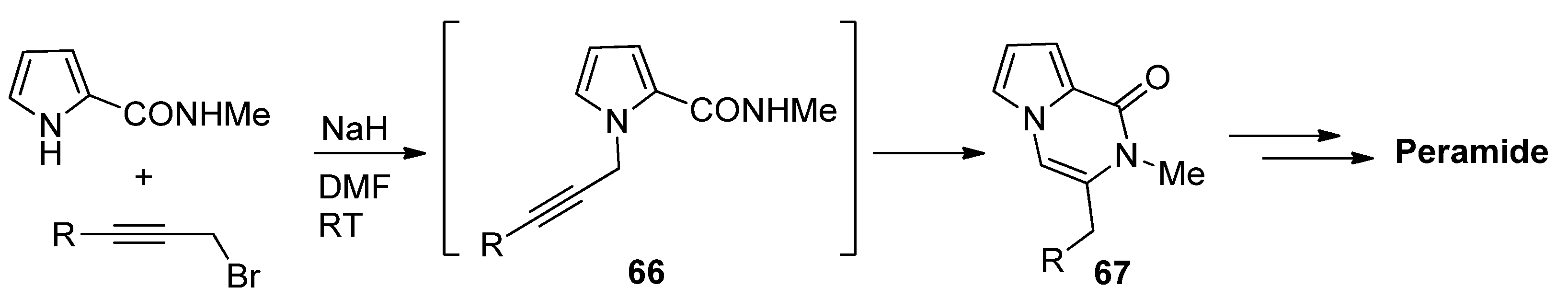

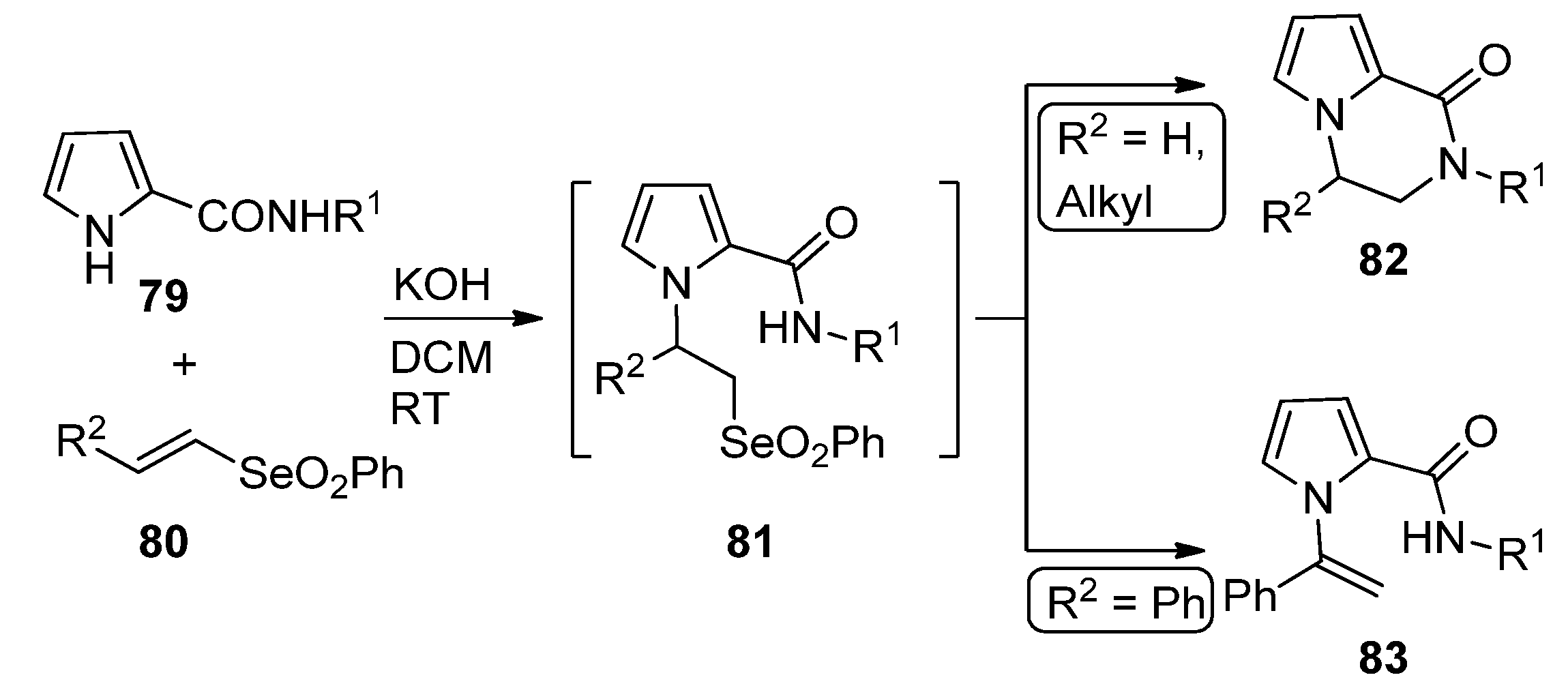

2.1. Starting from 2-Monosubstituted Pyrroles

2.2. Starting from 1-Monosubstituted Pyrroles

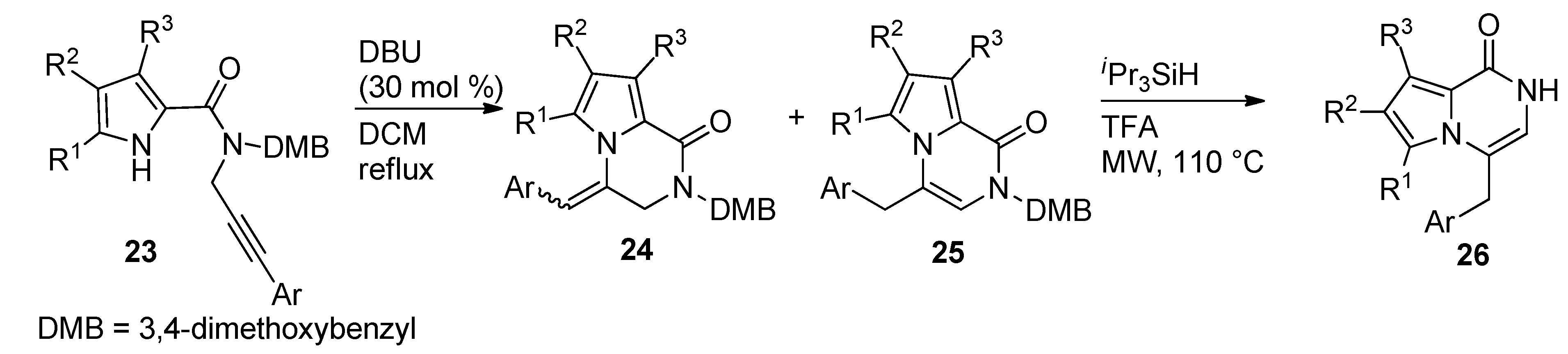

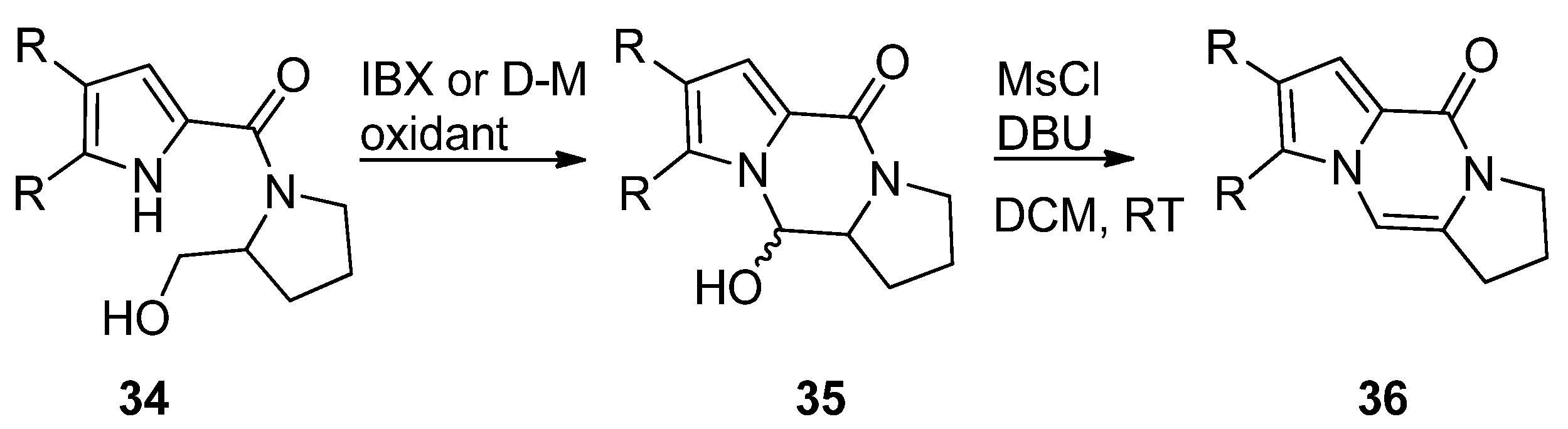

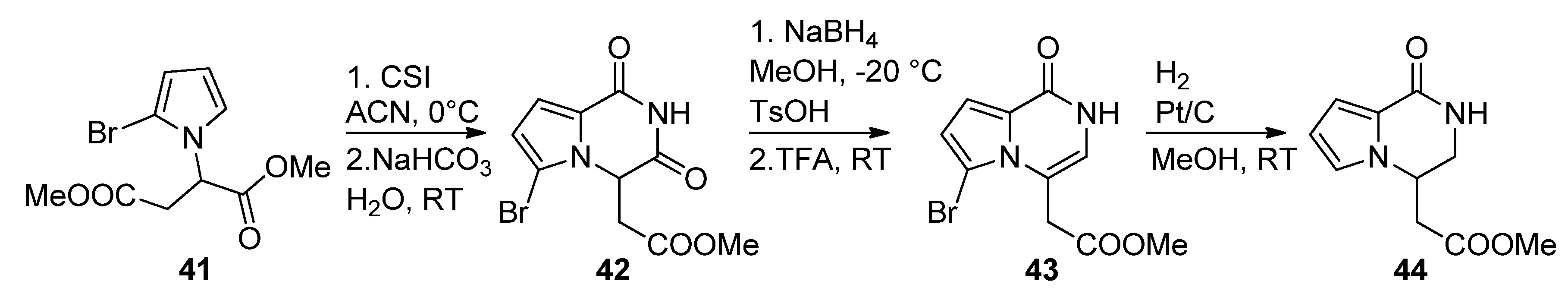

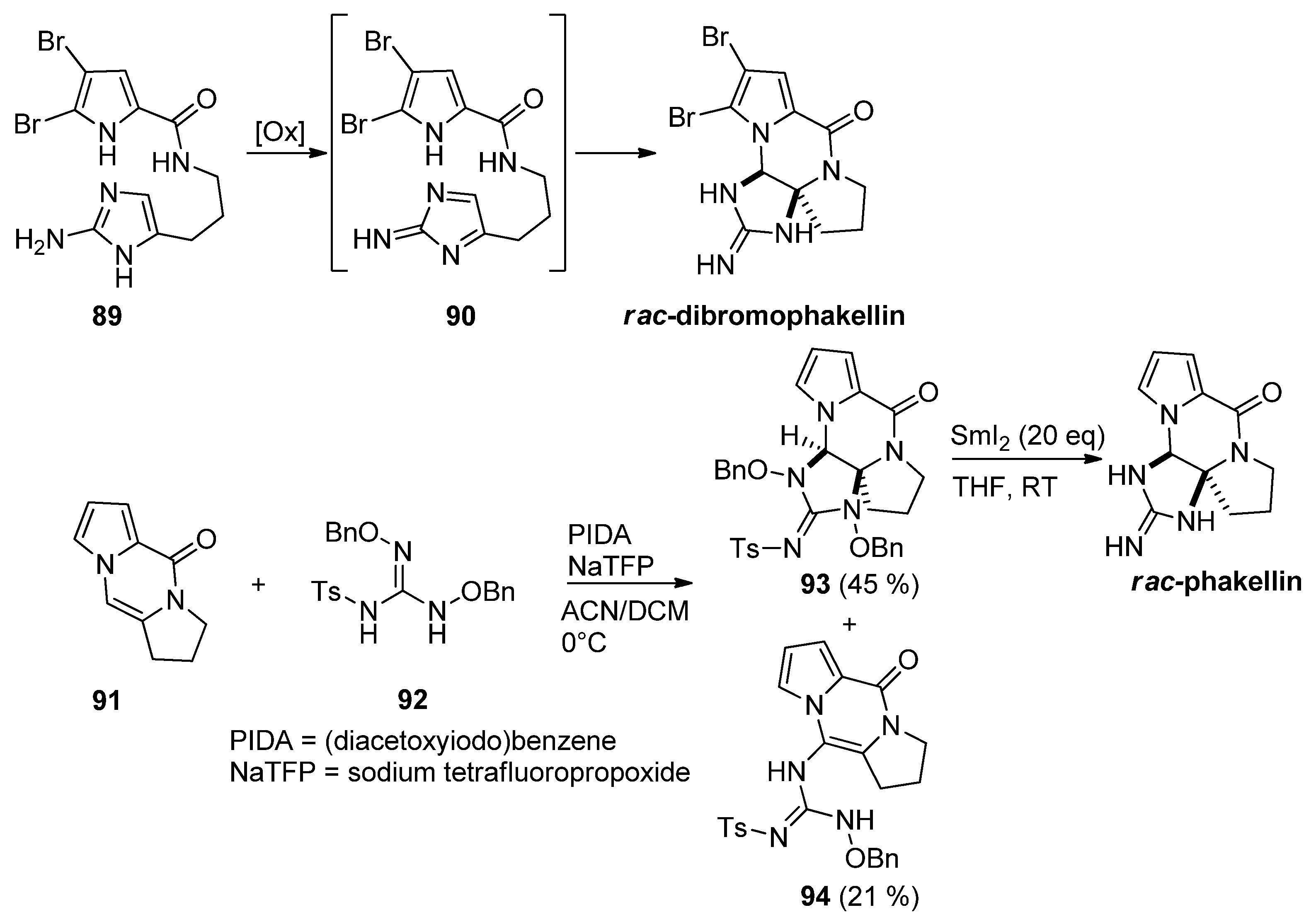

2.3. Starting from 1,2-Disubstituted Pyrroles

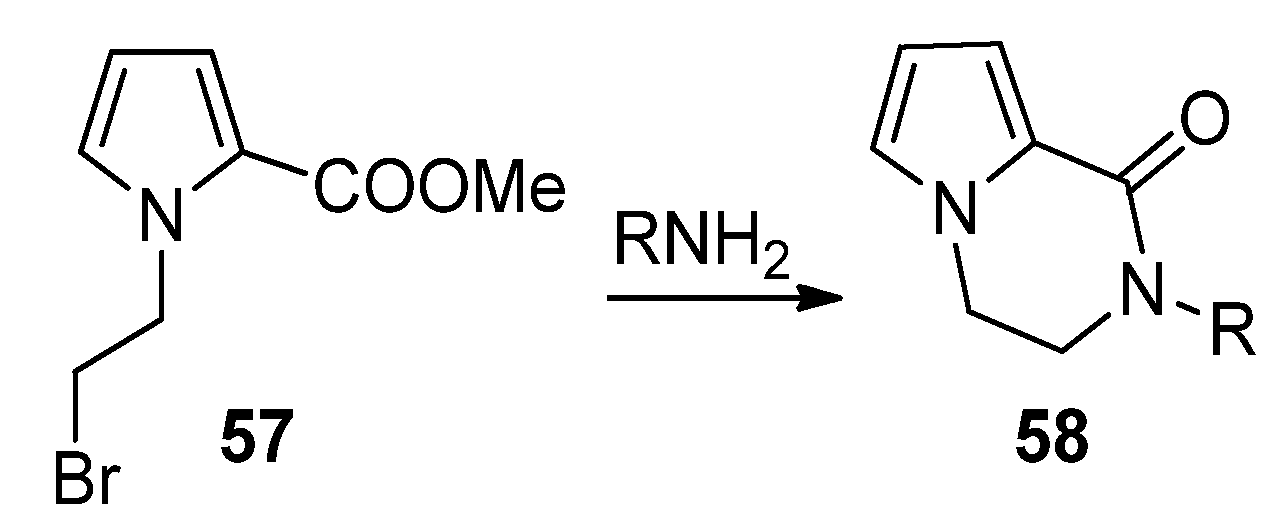

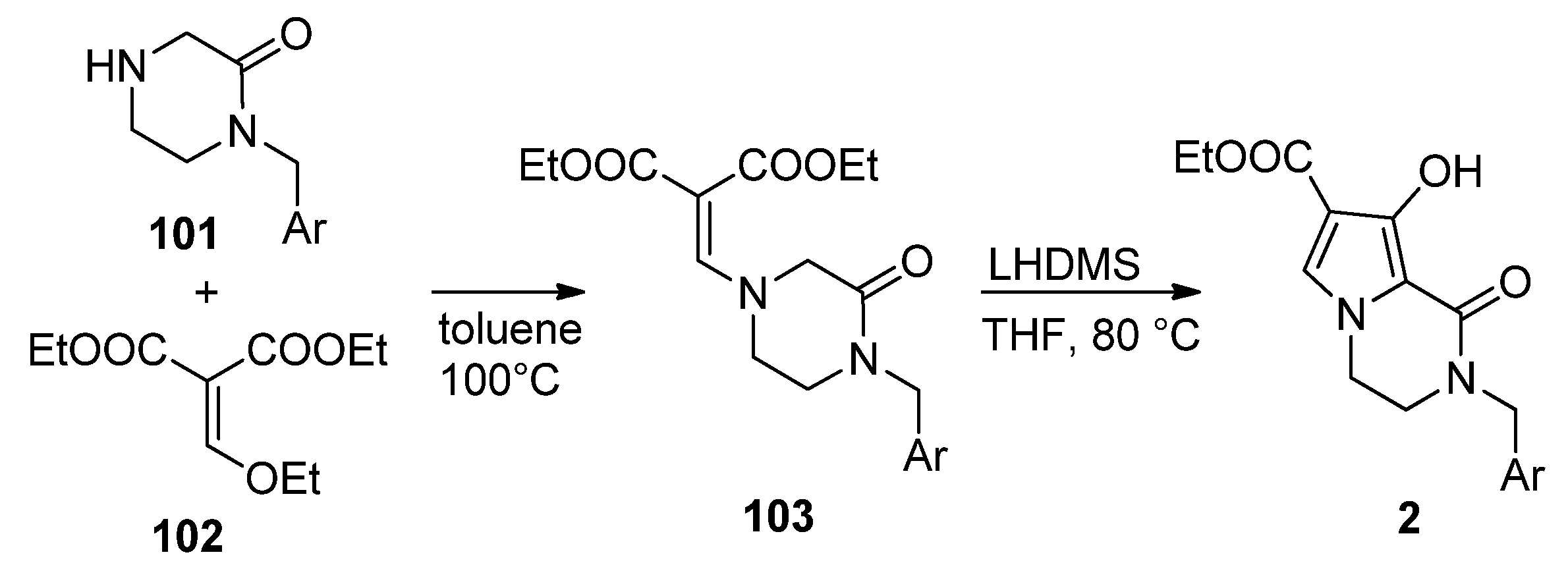

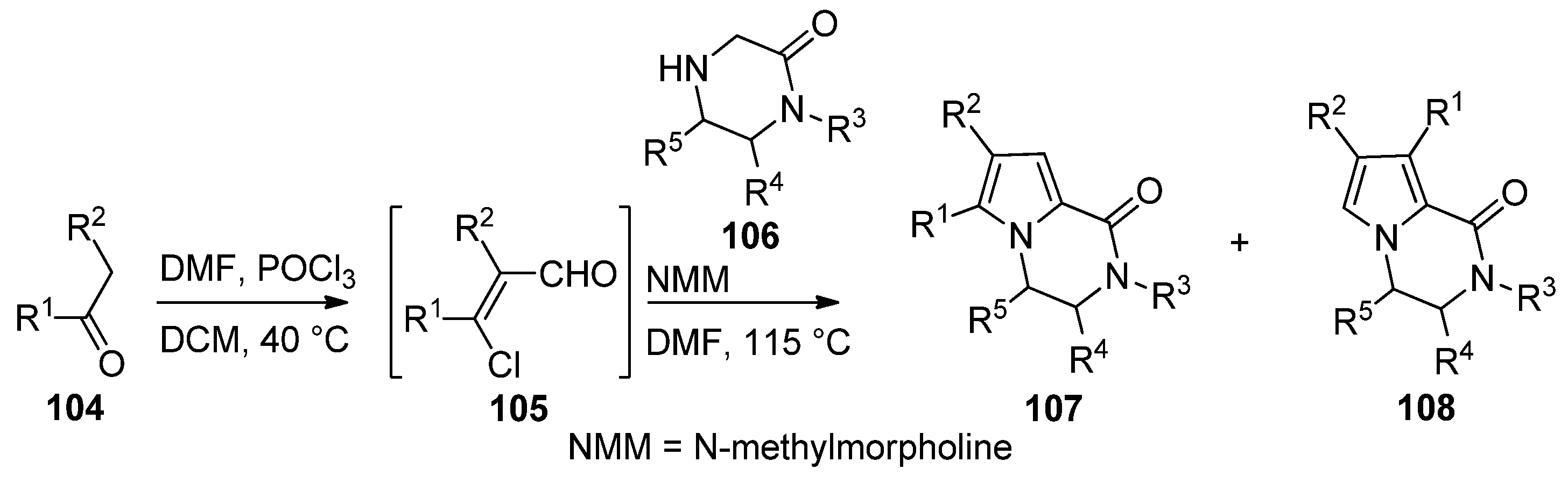

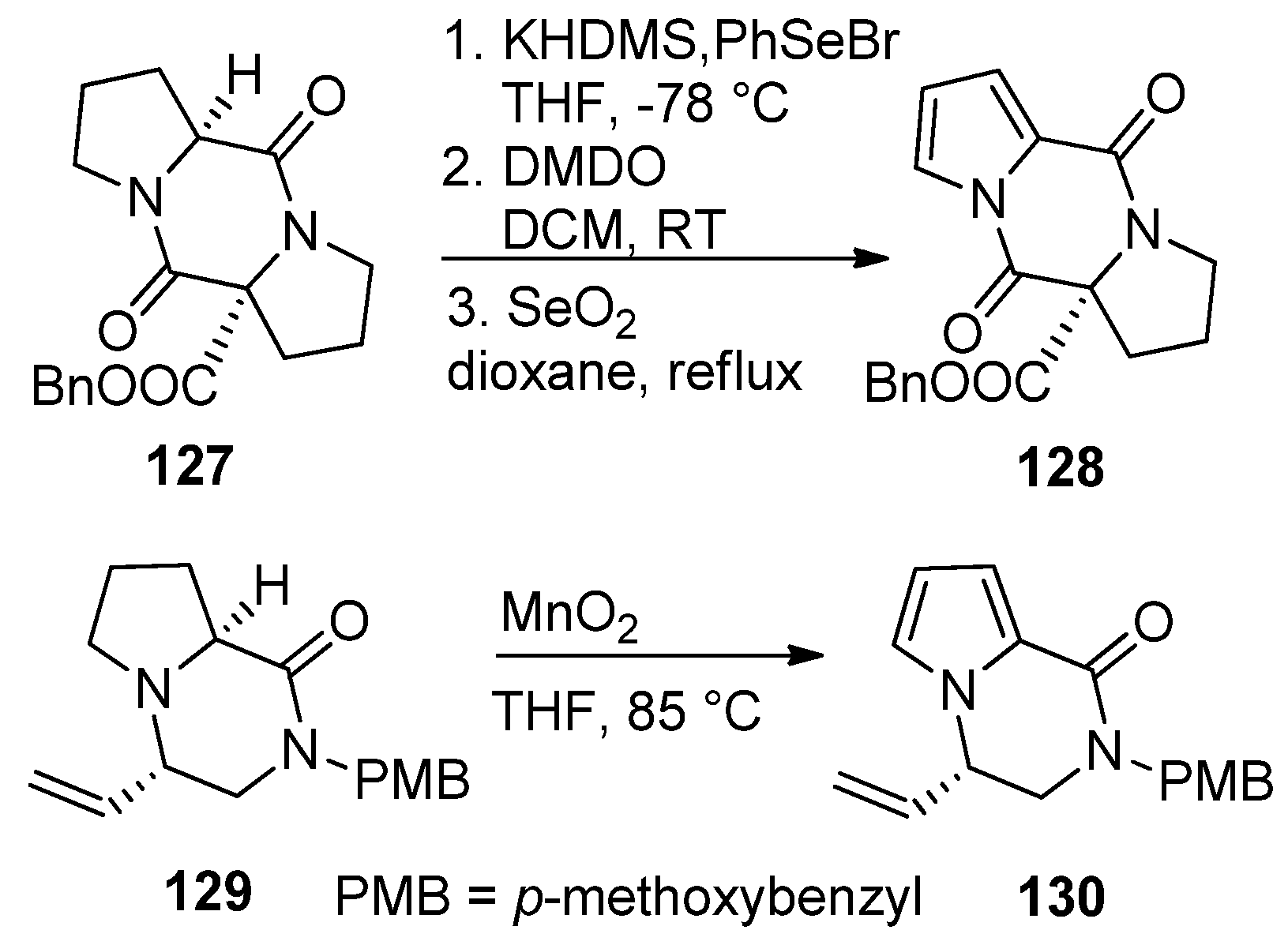

2.4. Fusion of a Pyrrole to a Pyrazinone Derivative

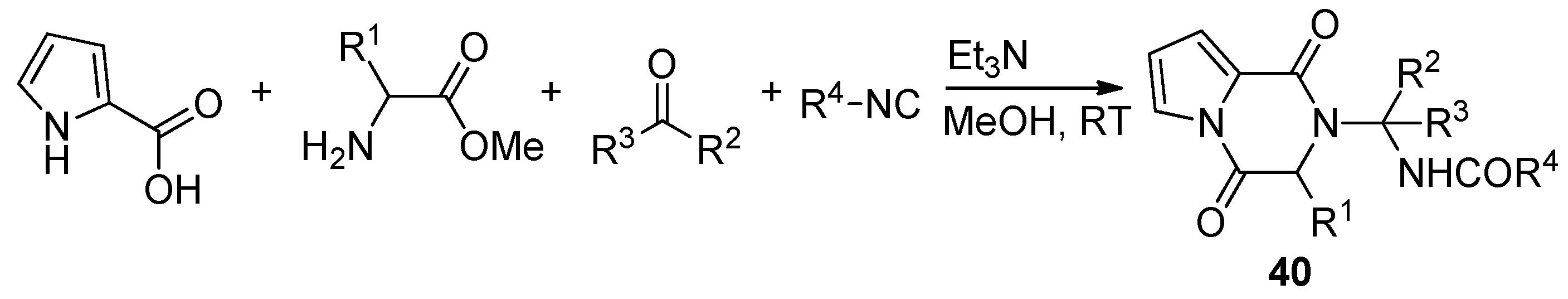

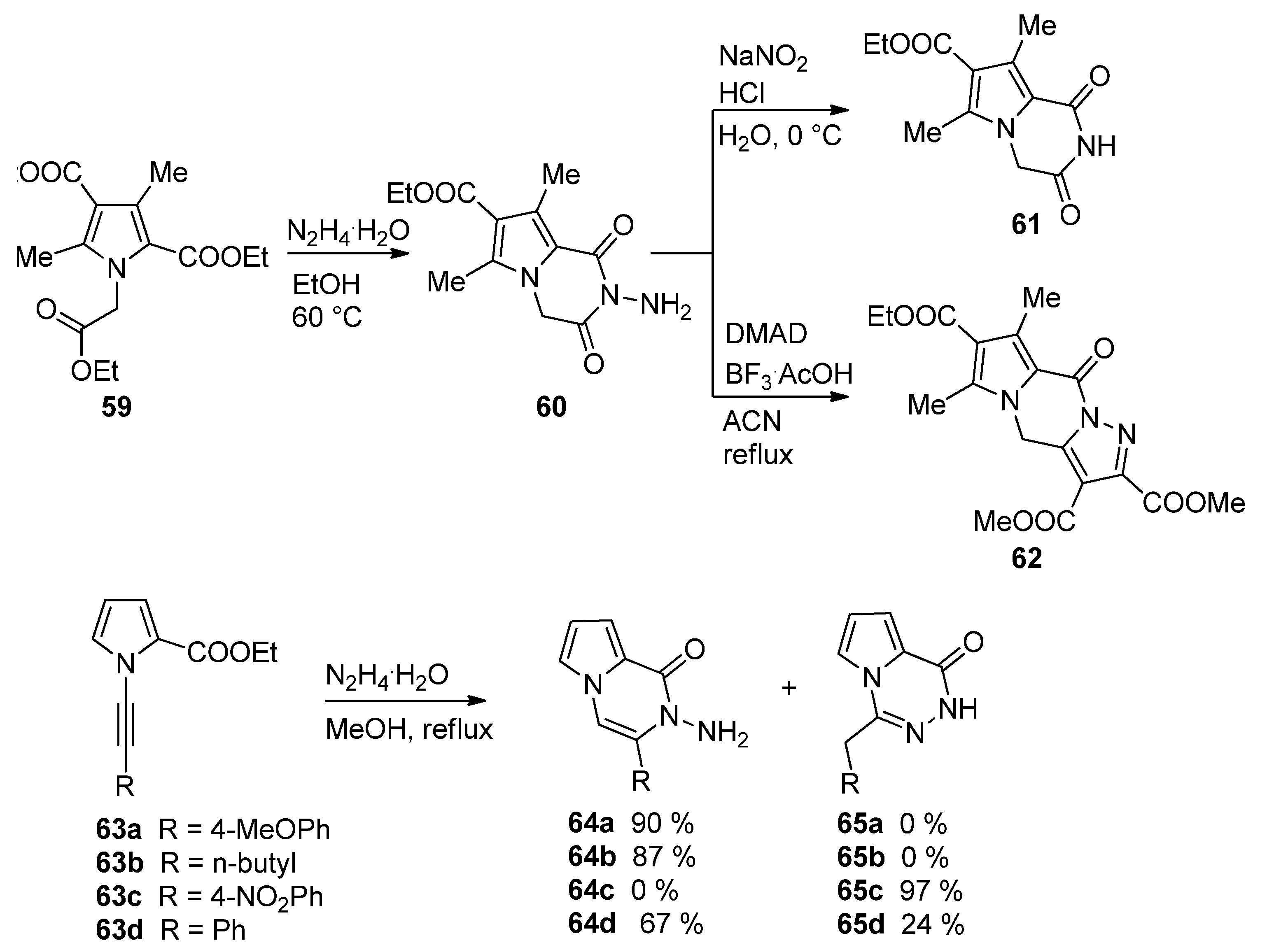

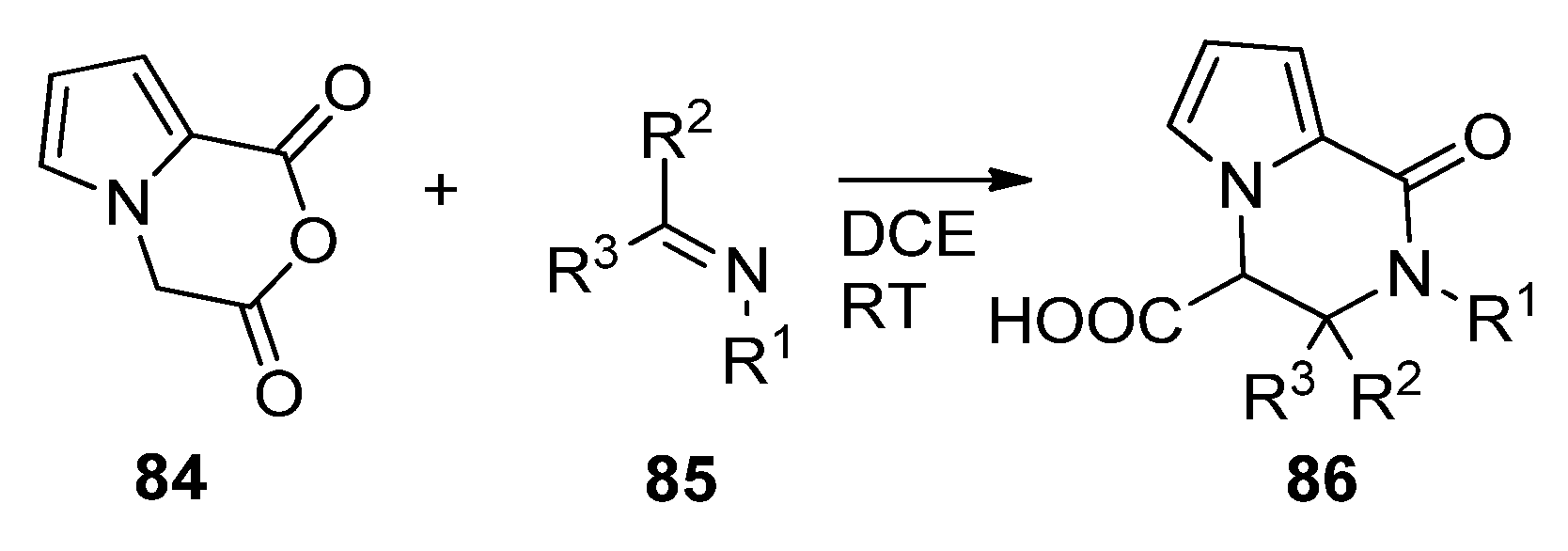

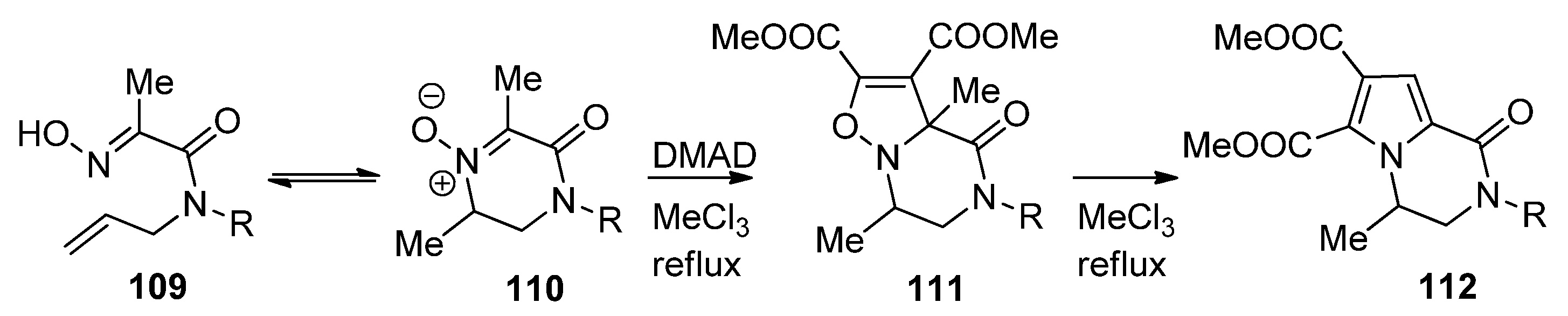

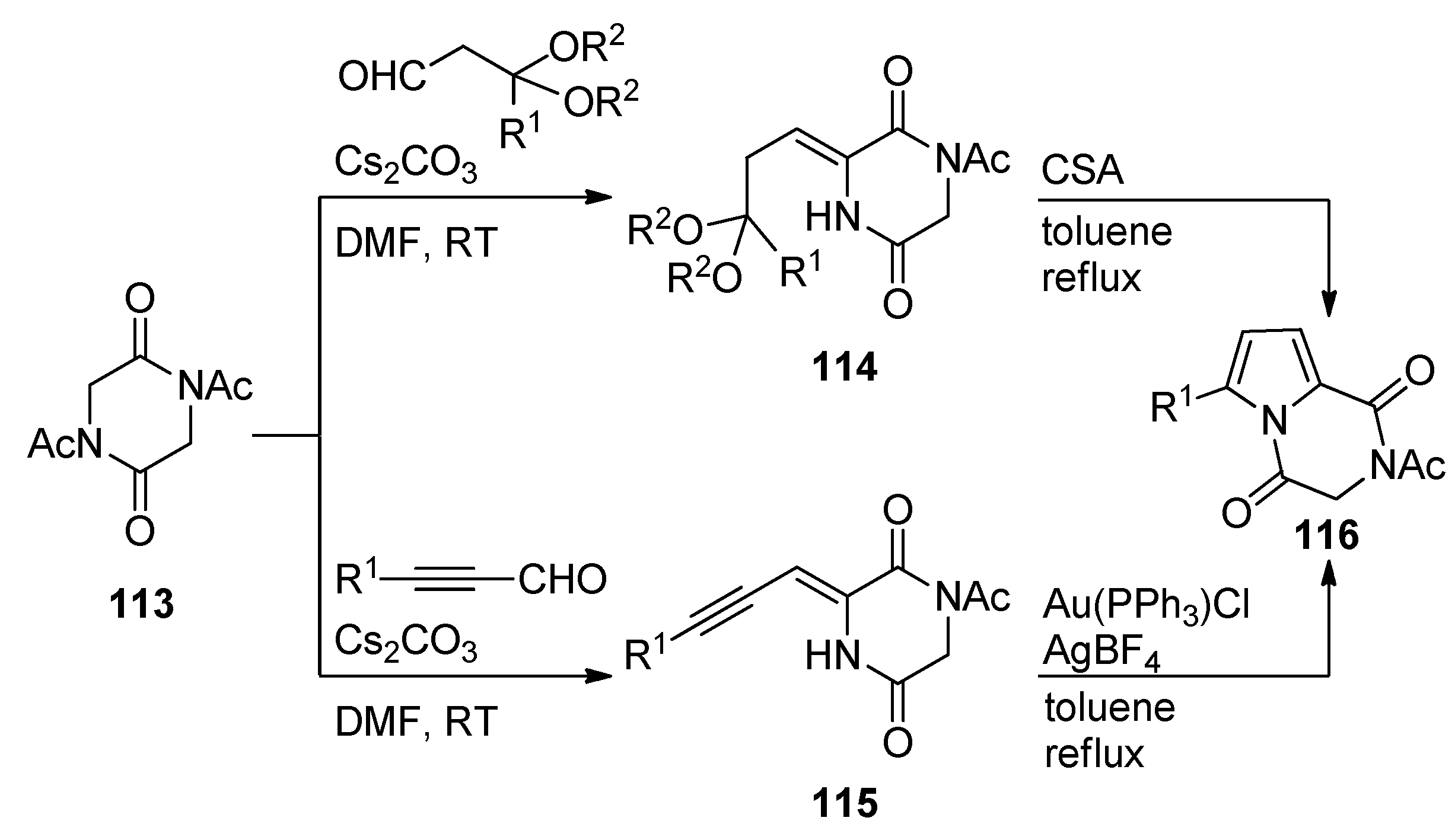

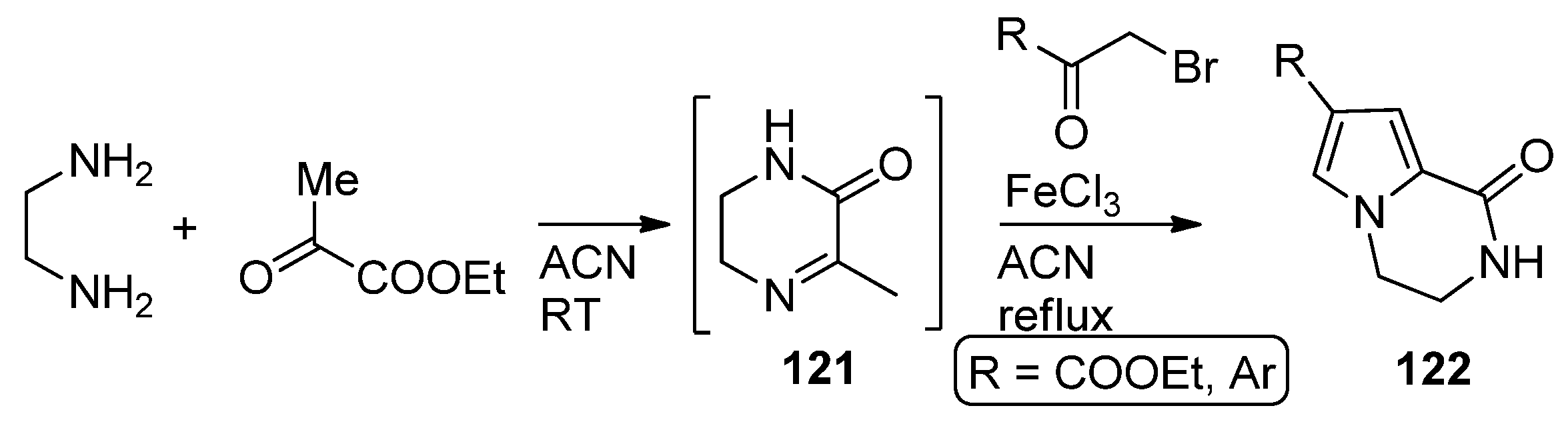

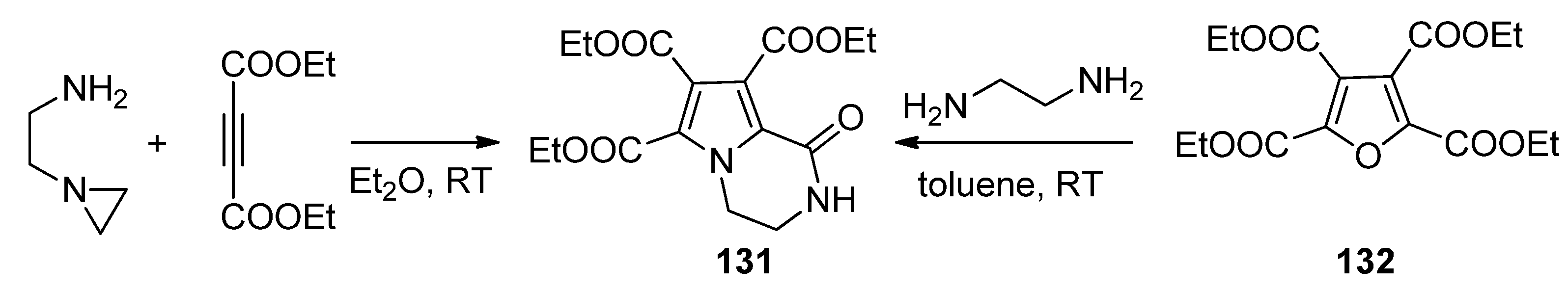

2.5. Multicomponent Reactions

2.6. Miscellaneous

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ac | Acetyl |

| ACN | Acetonitrile |

| AcOH | Acetic acid |

| Ar | Aryl |

| Bn | Benzyl |

| Boc | Tert-butoxycarbonyl |

| CCR | Castagnoli–Cushman reaction |

| CSA | Camphorsulfonic acid |

| CSI | Chlorosulfonyl isocyanate |

| dba | Dibenzylideneacetone |

| DBU | 1,8-Diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene |

| DCE | 1,2-dichloroethane |

| DCM | Dichloromethane |

| DDQ | 2,3-Dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone |

| DIBAH | Diisopropylaluminium hydride |

| DIPEA | Diisopropylethylamine |

| D-M | Dess–Martin |

| DMAD | Dimethyl acetylenedicarboxylate |

| DMB | 3,4-Dimethoxybenzyl |

| DMDO | Dimethyldioxirane |

| DMF | Dimethylformamide |

| DMSO | Dimethylsulfoxide |

| Et | Ethyl |

| Fmoc | Fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl |

| hfacac | Hexafluoroacetylacetone |

| IBX | 2-iodobenzoic acid |

| LHDMS | Lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide |

| Me | Methyl |

| MeOH | Methanol |

| NMM | N-methylmorpholine |

| Ox | Oxidation |

| PG | Protecting group |

| Ph | Phenyl |

| PIDA | Diacetoxyiodobenzene |

| PMP | 4-methoxyphenyl |

| PPA | Polyphosphoric acid |

| RT | Room Temperature |

| S-Phos | 2-Dicyclohexylphosphino-2′,6′-dimethoxybiphenyl |

| TBS | Tertbutyl silyl |

| tBu | Tert butyl |

| TFA | Trifluoroacetic acid |

| TFP | Tetrafluoropropoxide |

| THF | Tetrahydrofuran |

| Tr | Trityl |

| Ts | Tosyl |

References

- Taylor, A.R.D.; Maccoss, M.; Lawson, A.D.G. Supporting Information Rings in Drugs. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 5845–5859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitaku, E.; Smith, D.T.; Njardarson, J.T. Analysis of the Structural Diversity, Substitution Patterns, and Frequency of Nitrogen Heterocycles among U.S. FDA Approved Pharmaceuticals. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 10257–10274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, T.J.; Macdonald, S.J.; Young, R.J.; Pickett, S.D. The impact of aromatic ring count on compound developability: Further insights by examining carbo- and hetero-aromatic and -aliphatic ring types. Drug Discov. Today 2011, 16, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cafieri, F.; Fattorusso, E.; Mangoni, A.; Taglialatela-Scafati, O. Longamide and 3,7-dimethylisoguanine, two novel alkaloids from the marine sponge Agelas longissima. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 7893–7896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemoto, H.; Tsuda, M.; Kobayashi, J. Mukanadins A−C, New Bromopyrrole Alkaloids from Marine SpongeAgelasnakamurai. J. Nat. Prod. 1999, 62, 1581–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cafieri, F.; Fattorusso, E.; Taglialatela-Scafati, O. Novel Bromopyrrole Alkaloids from the SpongeAgelas dispar. J. Nat. Prod. 1998, 61, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancini, I.; Guella, G.; Amade, P.; Roussakis, C.; Pietra, F. Hanishin, a Semiracemic, Bioactive C9 Alkaloid of the Axinellid Sponge Acanthella carteri from the Hanish Islands. A Shunt Metabolite? Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 6271–6274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wu, J.; An, B.; De Voogd, N.J.; Cheng, W.; Lin, W. Bromopyrrole Alkaloids with the Inhibitory Effects against the Biofilm Formation of Gram Negative Bacteria. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fattorusso, E.; Taglialatela-Scafati, O. Two novel pyrrole-imidazole alkaloids from the Mediterranean sponge Agelas oroides. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 9917–9922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, M.; Yasuda, T.; Fukushi, E.; Kawabata, J.; Sekiguchi, M.; Fromont, J.; Kobayashi, J. Agesamides A and B, Bromopyrrole Alkaloids from SpongeAgelasSpecies: Application of DOSY for Chemical Screening of New Metabolites. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 4235–4238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, G.R.; McNulty, J.; Herald, D.L.; Doubek, D.L.; Chapuis, J.-C.; Schmidt, J.M.; Tackett, L.P.; Boyd, M.R. Antineoplastic Agents. 362. Isolation and X-ray Crystal Structure of Dibromophakellstatin from the Indian Ocean SpongePhakellia mauritiana1. J. Nat. Prod. 1997, 60, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ambrosio, M.; Guerriero, A.; Ribes, O.; Pusset, J.; Leroy, S.; Pietra, F. Agelastatin a, a new skeleton cytotoxic alkaloid of the oroidin family. Isolation from the axinellid sponge Agelas dendromorpha of the coral sea. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1993, 1305–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.W.; Jímenez, D.R.; Molinski, T.F. Agelastatins C and D, New Pentacyclic Bromopyrroles from the SpongeCymbastelasp., and Potent Arthropod Toxicity of (−)-Agelastatin A. J. Nat. Prod. 1998, 61, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnel, R.B.; Gehrken, H.P.; Scheuer, P.J. Palau’amine: A cytotoxic and immunosuppressive hexacyclic bisguanidine antibiotic from the sponge Stylotella agminata. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 3376–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, D.; Hunt, M.B.; Gaynor, D.L. Peramine, a novel insect feeding deterrent from ryegrass infected with the endophyte Acremonium loliae. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1986, 935–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, R.; Sood, S.; Mohr, K.I.; Kunze, B.; Irschik, H.; Stadler, M.; Müller, R. Nannozinones and Sorazinones, Unprecedented Pyrazinones from Myxobacteria. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 2545–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Liu, X.; Guo, H.; Ren, B.; Chen, C.; Piggott, A.; Yu, K.; Gao, H.; Wang, Q.; Liu, M.; et al. Brevianamides with Antitubercular Potential from a Marine-Derived Isolate of Aspergillus versicolor. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 4770–4773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigos, A. Macrophominol, a diketopiperazine from cultures of Macrophomina phaseolina. Phytochemistry 1995, 40, 1697–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grube, A.; Köck, M. Oxocyclostylidol, an Intramolecular Cyclized Oroidin Derivative from the Marine Sponge Stylissacaribica§. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 1212–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, S.; Siegel, D.S.; Morrison, K.C.; Hergenrother, P.J.; Movassaghi, M. Synthesis and Anticancer Activity of All Known (−)-Agelastatin Alkaloids. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 11970–11984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scala, F.; Fattorusso, E.; Menna, M.; Taglialatela-Scafati, O.; Tierney, M.; Kaiser, M.; Tasdemir, D. Bromopyrrole Alkaloids as Lead Compounds against Protozoan Parasites. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 2162–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lansdell, T.A.; Hewlett, N.M.; Skoumbourdis, A.P.; Fodor, M.D.; Seiple, I.B.; Su, S.; Baran, P.S.; Feldman, K.S.; Tepe, J.J. Palau’amine and Related Oroidin Alkaloids Dibromophakellin and Dibromophakellstatin Inhibit the Human 20S Proteasome. J. Nat. Prod. 2012, 75, 980–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brimble, M.A.; Rowanb, D.D. Synthesis of peramine, an insect feeding deterrent mycotoxin from Acremonium lolii. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1988, 4, 978–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashiko, T.; Kumagai, N.; Shibasaki, M. An Improved Lanthanum Catalyst System for Asymmetric Amination: Toward a Practical Asymmetric Synthesis of AS-3201 (Ranirestat). Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 2725–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, K.M.; Méndez-Andino, J.; Colson, A.-O.; Hu, X.E.; Wos, J.A.; Mitchell, M.C.; Hodge, K.; Howard, J.; Paris, J.L.; Dowty, M.; et al. Novel pyrazolopiperazinone- and pyrrolopiperazinone-based MCH-R1 antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 657–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, T.E.; Kim, B.; Staas, D.D.; Lyle, T.A.; Young, S.D.; Vacca, J.P.; Zrada, M.M.; Hazuda, D.J.; Felock, P.J.; Schleif, W.A.; et al. 8-Hydroxy-3,4-dihydropyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazine-1(2H)-one HIV-1 integrase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 6511–6515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheli, F.; Cavanni, P.; Di Fabio, R.; Marchioro, C.; Donati, D.; Faedo, S.; Maffeis, M.; Sabbatini, F.M.; Tranquillini, M.E. From pyrroles to pyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazinones: A new class of mGluR1 antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 1342–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, R.A.; Bethel, P.; Cook, C.; Davies, E.; Debreczeni, J.E.; Fairley, G.; Feron, L.; Flemington, V.; Graham, M.A.; Greenwood, R.; et al. Structure-Guided Discovery of Potent and Selective Inhibitors of ERK1/2 from a Modestly Active and Promiscuous Chemical Start Point. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 3438–3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casuscelli, F.; Ardini, E.; Avanzi, N.; Casale, E.; Cervi, G.; D’Anello, M.; Donati, D.; Faiardi, D.; Ferguson, R.D.; Fogliatto, G.; et al. Discovery and optimization of pyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazinones leads to novel and selective inhibitors of PIM kinases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 7364–7380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiokawa, Z.; Kashiwabara, E.; Yoshidome, D.; Fukase, K.; Inuki, S.; Fujimoto, Y. Discovery of a Novel Scaffold as an Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) Inhibitor Based on the Pyrrolopiperazinone Alkaloid, Longamide B. ChemMedChem 2016, 11, 2682–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rok, F. 6-membered pyrrololactams: An overview of current synthetic approaches to their preparation. Curr. Org. Chem. 2018, 22, 2780–2800. [Google Scholar]

- Bandini, M.; Eichholzer, A.; Monari, M.; Piccinelli, F.; Umani-Ronchi, A. Versatile Base-Catalyzed Route to Polycyclic Heteroaromatic Compounds by Intramolecular Aza-Michael Addition. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 2007, 2917–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banwell, M.G.; Bray, A.M.; Willis, A.C.; Wong, D.J. First syntheses of the pyrroloketopiperazine marine natural products (±)-longamide, (±)-longamide B, (±)-longamide B methyl ester and (±)-hanishin. New J. Chem. 1999, 23, 687–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papeo, G.; Frau, M.A.G.-Z.; Borghi, D.; Varasi, M. Total synthesis of (±)-cyclooroidin. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 8635–8638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandini, M.; Bottoni, A.; Eichholzer, A.; Miscione, G.P.; Stenta, M. Asymmetric Phase-Transfer-Catalyzed Intramolecular N-Alkylation of Indoles and Pyrroles: A Combined Experimental and Theoretical Investigation. Chem. A Eur. J. 2010, 16, 12462–12473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa, Y.; Yamaoka, T.; Nakano, A.K.; Kotsuki, H. Synthesis of (−)-Agelastatin A by [3.3] Sigmatropic Rearrangement of Allyl Cyanate. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 2989–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.A.; Deng, J. Asymmetric Total Synthesis of (−)-Agelastatin A Using Sulfinimine (N-Sulfinyl Imine) Derived Methodologies. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 621–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domostoj, M.M.; Irving, E.; Scheinmann, F.; Hale, K.J. New Total Synthesis of the Marine Antitumor Alkaloid (−)-Agelastatin A. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 2615–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, T.; Sakamoto, R.; Akakura, M.; Maruoka, K. Stereocontrolled Synthesis of Vicinal Diamines by Organocatalytic Asymmetric Mannich Reaction of N-Protected Aminoacetaldehydes: Formal Synthesis of (−)-Agelastatin A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 7516–7520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchimochi, I.; Kitamura, Y.; Aoyama, H.; Akai, S.; Nakai, K.; Yoshimitsu, T. Total synthesis of (−)-agelastatin A: An SH2′ radical azidation strategy. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 9893–9896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, D.P.; Wardrop, D.J. Total Synthesis of (±)-Agelastatin A, A Potent Inhibitor of Osteopontin-Mediated Neoplastic Transformations. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 1341–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hama, N.; Matsuda, T.; Sato, T.; Chida, N. Total Synthesis of (−)-Agelastatin A: The Application of a Sequential Sigmatropic Rearrangement. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 2687–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, K.S.; Saunders, J.C. Alkynyliodonium Salts in Organic Synthesis. Application to the Total Synthesis of (−)-Agelastatin A and (−)-Agelastatin B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 9060–9061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, K.S.; Saunders, J.C.; Wrobleski, M.L. Alkynyliodonium Salts in Organic Synthesis. Development of a Unified Strategy for the Syntheses of (−)-Agelastatin A and (−)-Agelastatin B. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 7096–7109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, J.C.P.; Romo, D. Bioinspired Total Synthesis of Agelastatin A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 6870–6873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duspara, P.A.; Batey, R.A. A Short Total Synthesis of the Marine Sponge Pyrrole-2-aminoimidazole Alkaloid (±)-Agelastatin A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 10862–10866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöverlein, C.; Breckle, G.; Lindel, T. Diels−Alder Reactions of Oroidin and Model Compounds. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 819–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beccalli, E.M.; Broggini, G.; Martinelli, M.; Paladino, G.; Maria, B.E. Pd-catalyzed intramolecular cyclization of pyrrolo-2-carboxamides: Regiodivergent routes to pyrrolo-pyrazines and pyrrolo-pyridines. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 1077–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llauger, L.; Bergami, C.; Kinzel, O.D.; Lillini, S.; Pescatore, G.; Torrisi, C.; Jones, P. A novel base-mediated intramolecular hydroamination to build fused heteroaryl pyrazinones. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, M.R.; Yousufuddin, M.; Lovely, C.J. Diversity-Oriented Approach to Pyrrole-Imidazole Alkaloid Frameworks. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 1382–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pescatore, G.; Branca, D.; Fiore, F.; Kinzel, O.; Bufi, L.L.; Muraglia, E.; Orvieto, F.; Rowley, M.; Toniatti, C.; Torrisi, C.; et al. Identification and SAR of novel pyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazin-1(2H)-one derivatives as inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 1094–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, K.-Y.; Cheng, Q.; Zhuo, C.-X.; Dai, L.-X.; You, S. An Iridium(I) N-Heterocyclic Carbene Complex Catalyzes Asymmetric Intramolecular Allylic Amination Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 8113–8116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, C.-X.; Zhang, X.; You, S.-L. Enantioselective Synthesis of Pyrrole-Fused Piperazine and Piperazinone Derivatives via Ir-Catalyzed Asymmetric Allylic Amination. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 5307–5310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchais, S.; Al Mourabit, A.; Ahond, A.; Poupat, C.; Potier, P. Synthesis of the marine carbinolamine (+/−) longamide control of N-1 and C-3 bromopyrrole nucleophilicity. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 5519–5522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa, A.C.B.; Yakushijin, K.; Horne, D.A. Controlling cyclizations of 2-pyrrolecarboxamidoacetals. Facile solvation of β-amido aldehydes and revised structure of synthetic homolongamide. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 4295–4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allmann, T.C.; Moldovan, R.-P.; Jones, P.G.; Lindel, T. Synthesis of Hydroxypyrrolone Carboxamides Employing Selectfluor. Chem. A Eur. J. 2015, 22, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquot, D.E.; Hoffmann, H.; Polborn, K.; Lindel, T. Synthesis of the dipyrrolopyrazinone core of dibromophakellstatin and related marine alkaloids. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 3699–3702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, R.; Yu, E.; Incarvito, C.D.; Austin, D.J. Hypervalent Iodine-Mediated Vicinal Syn Diazidation: Application to the Total Synthesis of (±)-Dibromophakellstatin. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 3881–3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travert, N.; Martin, M.-T.; Bourguet-Kondracki, M.-L.; Al-Mourabit, A. Regioselective intramolecular N1–C3 cyclizations on pyrrole–proline to ABC tricycles of dibromophakellin and ugibohlin. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindel, T.; Zöllinger, M.; Mayer, P. Enantioselective Total Synthesis of (-)-Dibromophakellstatin. Synlett 2007, 2007, 2756–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travert, N.; Al-Mourabit, A. A Likely Biogenetic Gateway Linking 2-Aminoimidazolinone Metabolites of Sponges to Proline: Spontaneous Oxidative Conversion of the Pyrrole-Proline-Guanidine Pseudo-peptide to Dispacamide A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 10252–10253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Ermolenko, L.; Gabant, M.; Vergne, C.; Moriou, C.; Retailleau, P.; Al-Mourabit, A. Pyrrole-Assisted and Easy Oxidation of Cyclic α-Amino Acid- Derived Diketopiperazines under Mild Conditions. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011, 353, 1525–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermolenko, L.; Zhaoyu, H.; Lejeune, C.; Vergne, C.; Ratinaud, C.; Nguyen, T.B.; Al-Mourabit, A. Concise synthesis of Didebromohamacanthin A and Demethylaplysinopsine: Addition of Ethylenediamine and Guanidine Derivatives to the Pyrrole-Amino Acid Diketopiperazines in Oxidative Conditions. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 872–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelli, M.R.; Scheerer, J.R. Synthesis of Peramine, an Anti-insect Defensive Alkaloid Produced by Endophytic Fungi of Cool Season Grasses. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 1189–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petsi, M.; Zografos, A.L. 2,5-Diketopiperazine Catalysts as Activators of Dioxygen in Oxidative Processes. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 7093–7099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Khan, S.; Singh, A.; Gauniyal, H.M.; Kumar, B.; Chauhan, P.M.S. Access to Indole- And Pyrrole-Fused Diketopiperazines via Tandem Ugi-4CR/Intramolecular Cyclization and Its Regioselective Ring-Opening by Intermolecular Transamidation. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 10211–10227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imaoka, T.; Akimoto, T.; Iwamoto, O.; Nagasawa, K. Total Synthesis of (+)-Dibromophakellin and (+)-Dibromophakellstatin. Chem. Asian J. 2010, 5, 1810–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imaoka, T.; Iwamoto, O.; Nagasawa, K.; Noguchi, K.-I. Total Synthesis of (+)-Dibromophakellin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 3799–3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, L.A.; Valente, M.W.; Williams, R.M. A concise synthesis of d,l-brevianamide B via a biomimetically-inspired IMDA construction. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 5195–5200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negoro, T.; Murata, M.; Ueda, S.; Fujitani, B.; Ono, Y.; Kuromiya, A.; Komiya, M.; Suzuki, K.; Matsumoto, J.-I. Novel, Highly Potent Aldose Reductase Inhibitors: (R)-(−)-2-(4-Bromo-2-fluorobenzyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazine- 4-spiro-3‘-pyrrolidine-1,2‘,3,5‘-tetrone (AS-3201) and Its Congeners. J. Med. Chem. 1998, 41, 4118–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.-G.; Ma, Y.-Y.; Peng, W.; Zhou, A.-Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, L.; Du, Z.; Zhang, K. Total synthesis and cytotoxic activities of longamide B, longamide B methyl ester, hanishin, and their analogues. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brimble, M.A.; Rowan, D.D. Synthesis of the insect feeding deterrent peramine via Michael addition of a pyrrole anion to a nitroalkene. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 1990, 1, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Sivappa, R.; Yousufuddin, M.; Lovely, C.J. Asymmetric Total Synthesis ofent-Cyclooroidin. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 4940–4943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Das Adhikary, N.; Kwon, S.; Chung, W.-J.; Koo, S. One-Pot Conversion of Carbohydrates into Pyrrole-2-carbaldehydes as Sustainable Platform Chemicals. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 7693–7701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, C.; Barrett, C.; Brunson, M.; Chin, J.; England, D.; Garcia, K.; Gigstad, K.; Gould, A.; Gutiérrez, J.; Hoar, K.; et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors derived from 1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazine and related heterocycles selective for the HDAC6 isoform. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 5450–5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surase, Y.B.; Samby, K.; Amale, S.R.; Sood, R.; Purnapatre, K.P.; Pareek, P.K.; Das, B.; Nanda, K.; Kumar, S.; Verma, A.K. Identification and synthesis of novel inhibitors of mycobacterium ATP synthase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 3454–3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukase, K.; Fujimoto, Y.; Shiokawa, Z.; Inuki, S. Efficient Synthesis of (–)-Hanishin, (–)-Longamide B, and (–)-Longamide B Methyl Ester through Piperazinone Formation from 1,2-Cyclic Sulfamidates. Synlett 2015, 27, 616–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Wang, X.; Bao, H.; Cheng, C.; Liu, N.; Hu, Y. Total Syntheses of (−)-Hanishin, (−)-Longmide B, and (−)-Longmide B Methyl Ester via a Novel Preparation of N-Substituted Pyrrole-2-Carboxylates. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 1062–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mszar, N.W.; Haeffner, F.; Hoveyda, A.H. NHC–Cu-Catalyzed Addition of Propargylboron Reagents to Phosphinoylimines. Enantioselective Synthesis of Trimethylsilyl-Substituted Homoallenylamides and Application to the Synthesis of S-(−)-Cyclooroidin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 3362–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brimble, M.; Brimble, M.; Hodges, R.; Lane, G. Synthesis of 2-Methylpyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazin-1(2h)-one. Aust. J. Chem. 1988, 41, 1583–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimitsu, T.; Ino, T.; Futamura, N.; Kamon, T.; Tanaka, T. Total Synthesis of the β-Catenin Inhibitor, (−)-Agelastatin A: A Second-Generation Approach Based on Radical Aminobromination. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 3402–3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigeoka, D.; Kamon, T.; Yoshimitsu, T.; Stephenson, C. Formal synthesis of (−)-agelastatin A: An iron(II)-mediated cyclization strategy. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2013, 9, 860–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Voievudskyi, M.; Astakhina, V.; Kryshchyk, O.; Petukhova, O.; Shyshkina, S. Synthesis and reactivity of novel pyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazine derivatives. Mon. Chem. 2015, 147, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenice, I.; Basceken, S.; Balci, M. Nucleophilic and electrophilic cyclization of N-alkyne-substituted pyrrole derivatives: Synthesis of pyrrolopyrazinone, pyrrolotriazinone, and pyrrolooxazinone moieties. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2017, 13, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cetinkaya, Y.; Balci, M. Selective synthesis of N-substituted pyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazin-1(2H)-one derivatives via alkyne cyclization. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 6698–6702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Yamamoto, Y.; Nishikawa, T. A concise synthesis of peramine, a metabolite of endophytic fungi. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2018, 82, 2053–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Wang, J.; Zhang, S. A Novel Synthesis of Arylpyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazinone Derivatives. Molecules 2004, 9, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dumas, D.J. Total synthesis of peramine. J. Org. Chem. 1988, 53, 4650–4653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujjinamatada, R.K. Substituted Tetrahydroquinoline Compounds as ROR Gamma Modulators. WO Patent No. 2016/185342 WIPO, 13 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt, J.F.M.; Williams, L.; Aggarwal, P.; Smith, C.D.; France, D. Palladium-catalyzed heteroallylation of unactivated alkenes—Synthesis of citalopram. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 3538–3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, C.D.; Phillips, D.; Tirla, A.; France, D.J. Catalytic Isohypsic-Redox Sequences for the Rapid Generation of Csp3-Containing Heterocycles. Chem. A Eur. J. 2018, 24, 17201–17204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boothe, J.R.; Shen, Y.; Wolfe, J.P. Synthesis of Substituted γ- and δ-Lactams via Pd-Catalyzed Alkene Carboamination Reactions. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 2777–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trost, B.M.; Dong, G. New Class of Nucleophiles for Palladium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Allylic Alkylation. Total Synthesis of Agelastatin A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 6054–6055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anderson, G.T.; Chase, C.E.; Koh, Y.-H.; Stien, D.; Weinreb, S.M.; Shang, M. Studies on Total Synthesis of the Cytotoxic Marine Alkaloid Agelastatin A. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 7594–7595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stien, D.; Anderson, G.T.; Chase, C.E.; Koh, Y.-H.; Weinreb, S.M. Total Synthesis of the Antitumor Marine Sponge Alkaloid Agelastatin A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 9574–9579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.-T.; Chen, A. Total synthesis of rac-longamide B. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 3459–3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trost, B.M.; Dong, G. A Stereodivergent Strategy to Both Product Enantiomers from the Same Enantiomer of a Stereoinducing Catalyst: Agelastatin A. Chem. A Eur. J. 2009, 15, 6910–6919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dong, G. Recent advances in the total synthesis of agelastatins. Pure Appl. Chem. 2010, 82, 2231–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trost, B.M.; Osipov, M.; Dong, G. Palladium-Catalyzed Dynamic Kinetic Asymmetric Transformations of Vinyl Aziridines with Nitrogen Heterocycles: Rapid Access to Biologically Active Pyrroles and Indoles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 15800–15807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Palomba, M.; Sancineto, L.; Marini, F.; Santi, C.; Bagnoli, L. A domino approach to pyrazino- indoles and pyrroles using vinyl selenones. Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 7156–7163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chizhova, M.; Khoroshilova, O.; Dar’In, D.; Krasavin, M. Unusually Reactive Cyclic Anhydride Expands the Scope of the Castagnoli–Cushman Reaction. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 12722–12733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chizhova, M.E.; Dar’In, D.V.; Krasavin, M. The Castagnoli–Cushman reaction of bicyclic pyrrole dicarboxylic anhydrides bearing electron-withdrawing substituents. Mendeleev Commun. 2020, 30, 496–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyn, A.P.; Kuzovkova, J.A.; Potapov, V.V.; Shkirando, A.M.; Kovrigin, D.I.; Tkachenko, S.E.; Ivachtchenko, A.V. An efficient synthesis of novel heterocycle-fused derivatives of 1-oxo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrazine using Ugi condensation. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 881–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kounde, C.S.; Yeo, H.-Q.; Wang, Q.-Y.; Wan, K.F.; Dong, H.; Karuna, R.; Dix, I.; Wagner, T.; Zou, B.; Simon, O.; et al. Discovery of 2-oxopiperazine dengue inhibitors by scaffold morphing of a phenotypic high-throughput screening hit. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 1385–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaoka, T.; Iwata, M.; Akimoto, T.; Nagasawa, K. Synthetic Approaches to Tetracyclic Pyrrole Imidazole Marine Alkaloids. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2013, 8, 961–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kovvuri, V.R.R.; Xue, H.; Romo, D. Generation and Reactivity of 2-Amido-1,3-diaminoallyl Cations: Cyclic Guanidine Annulations via Net (3 + 2) and (4 + 3) Cycloadditions. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 1407–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poullennec, K.G.; Romo, D. Enantioselective Total Synthesis of (+)-Dibromophakellstatin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 6344–6345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zöllinger, M.; Mayer, P.; Lindel, T. Total Synthesis of the Cytostatic Marine Natural Product Dibromophakellstatin via Three-Component Imidazolidinone Anellation. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 9431–9439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquot, D.E.N.; Zöllinger, M.; Lindel, T. Total Synthesis of the Marine Natural Productrac-Dibromophakellstatin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 2295–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; De, S.; Chen, C. Syntheses of cyclic guanidine-containing natural products. Tetrahedron 2015, 71, 1145–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seiple, I.B.; Su, S.; Young, I.S.; Lewis, C.A.; Yamaguchi, J.; Baran, P.S. Total Synthesis of Palau’amine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 49, 1095–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Namba, K.; Takeuchi, K.; Kaihara, Y.; Oda, M.; Nakayama, A.; Nakayama, A.; Yoshida, M.; Tanino, K. Total synthesis of palau’amine. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Robba, M.; Tembo, O.N.; Dallemagne, P.; Rault, S. An Efficient Synthesis of New Phenylpyrrolizine and Phenylpyrrolopyrazine Derivatives. Heterocycles 1993, 36, 2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, C.; Lim, N.-K.; Zhang, H. Two-Step Synthesis of 3,4-Dihydropyrrolopyrazinones from Ketones and Piperazin-2-ones. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 1252–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heaney, F.; Fenlon, J.; McArdle, P.; Cunningham, D. α-Keto amides as precursors to heterocycles—generation and cycloaddition reactions of piperazin-5-one nitrones. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2003, 1, 1122–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maisto, S.K.; Leersnyder, A.P.; Pudner, G.L.; Scheerer, J.R. Synthesis of Pyrrolopyrazinones by Construction of the Pyrrole Ring onto an Intact Diketopiperazine. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 9264–9271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piltan, M.; Moradi, L.; Abasi, G.; Zarei, S.A.; Wolfe, J.P. A one-pot catalyst-free synthesis of functionalized pyrrolo[1,2-a]quinoxaline derivatives from benzene-1,2-diamine, acetylenedicarboxylates and ethyl bromopyruvate. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2013, 9, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Piltan, M. One-Pot, Green and Efficient Synthesis of Pyrrolo[1,2-α]Quinoxalines in Water. J. Chem. Res. 2016, 40, 410–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, L.; Piltan, M.; Rostami, H.; Abasi, G. One-pot synthesis of pyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazines via three component reaction of ethylenediamine, acetylenic esters and nitrostyrene derivatives. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2013, 24, 740–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, A.; Abadi, M.H.; Ghanbaripour, R. An Efficient Approach to the Synthesis of Alkyl 7-Hydroxy-1-oxo-1,2,3,4- tetrahydropyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazine-8-carboxylates via a One-Pot, Three-Component Reaction. Synlett 2014, 25, 1705–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piltan, M. One-pot synthesis of pyrrolo[1,2-a]quinoxaline and pyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazine derivatives via the three-component reaction of 1,2-diamines, ethyl pyruvate and α-bromo ketones. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2014, 25, 1507–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert-Nicol, S.; Lessard, J.; Spino, C. A Photorearrangement To Construct the ABDE Tetracyclic Core of Palau’amine. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 2615–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, M.; Petkovic, M.; Jovanovic, P.; Simic, M.; Tasic, G.; Eric, S.; Savic, V. Proline Derived Bicyclic Derivatives through Metal Catalysed Cyclisations of Allenes: Synthesis of Longamide B, Stylisine D and their Derivatives. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 2020, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostyanovsky, R.G.; El’Natanov, Y.I.; Chervin, I.I.; Antipin, M.Y.; Lyssenko, K.A. Unusual reaction of aziridine dimer with acetylene dicarboxylates. Mendeleev Commun. 1997, 7, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Winant, P.; Horsten, T.; Gil de Melo, S.M.; Emery, F.; Dehaen, W. A Review of the Synthetic Strategies toward Dihydropyrrolo[1,2-a]Pyrazinones. Organics 2021, 2, 118-141. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/org2020011

Winant P, Horsten T, Gil de Melo SM, Emery F, Dehaen W. A Review of the Synthetic Strategies toward Dihydropyrrolo[1,2-a]Pyrazinones. Organics. 2021; 2(2):118-141. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/org2020011

Chicago/Turabian StyleWinant, Pieterjan, Tomas Horsten, Shaiani Maria Gil de Melo, Flavio Emery, and Wim Dehaen. 2021. "A Review of the Synthetic Strategies toward Dihydropyrrolo[1,2-a]Pyrazinones" Organics 2, no. 2: 118-141. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/org2020011