Synthesis, Crystal Structure and DFT Studies of a New Dinuclear Ag(I)-Malonamide Complex

Abstract

:1. Introduction

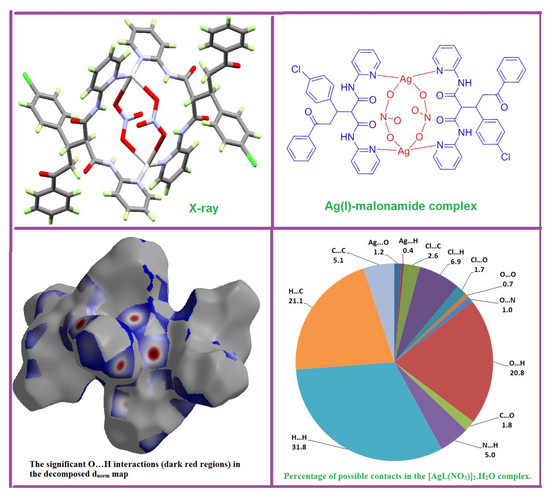

2. Results

Preparation of the Ligand (L) and Ag Complex

3. Discussion

3.1. X-ray Crystal Structure

3.2. Hirshfeld (HF) Analysis of Molecular Packing

3.3. FTIR and NMR Spectra

3.4. AIM Analyses

3.5. Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) Analyses

3.6. Continuous Shape Measure (CShM)

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Synthesis of the Silver(I) Complex

4.3. Computational Methods

4.4. X-ray Measurements

4.5. Hirshfeld Surface Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chu, G.H.; Gu, M.; Cassel, J.A.; Belanger, S.; Graczyk, T.M.; DeHaven, R.N.; Koblish, M.; Little, P.J.; DeHaven-Hudkins, D.L.; Dolle, R.E. Novel malonamide derivatives as potent κ opioid receptor agonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 1951–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, J.U.; Galley, G.; Jacobsen, H.; Czech, C.; David-Pierson, P.; Kitas, E.A.; Ozmen, L. Novel orally active, dibenzazepinone-based γ-secretase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 5918–5923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudette, F.; Raeppel, S.; Nguyen, H.; Beaulieu, N.; Beaulieu, C.; Dupont, I.; Macleod, A.R.; Besterman, J.M.; Vaisburg, A. Identification of potent and selective VEGFR receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors having new amide isostere headgroups. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 848–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barakat, A.; Islam, M.S.; Al-Majid, A.M.; Soliman, S.M.; Ghabbour, H.A.; Yousuf, S.; Choudhary, M.I.; Ul-Haq, Z. Synthesis, molecular structure, spectral analysis, and biological activity of new malonamide derivatives as α-glucosidase inhibitors. J. Mol. Struct. 2017, 1134, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Barakat, A.; Al-Majid, A.M.; Ghabbour, H.A.; Rahman, A.M.; Javaid, K.; Imad, R.; Yousuf, S.; Choudhary, M.I. A concise synthesis and evaluation of new malonamide derivatives as potential α-glucosidase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2016, 24, 1675–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, J.; Goodman., M. Synthesis of cyclic and acyclic partial retro-inverso modified enkephalins. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 1984, 23, 610–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, E.J.; Vitoux, B.; Marraud, M.; Sakarellos, C.; El-Masdouri, L.; Aubry, A. Conformational perturbations in retro-analogs of the tBuCO-Ala-Gly-NHiPr dipeptide Crystal structure of the retro-dipeptide with a reversed Ala-Gly amide bond. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 1989, 34, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dado, G.P.; Desper, J.M.; Holmgren, S.K.; Rito, C.J.; Gellman, S.H. Effects of covalent modifications on the solid-state folding and packing of N-malonylglycine derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 4834–4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoukry, A.F.; Shuaib, N.M.; Ibrahim, Y.A.; Malhas, R.N. Ionization of some derivatives of benzamide, oxamide and malonamide in DMF–water mixture. Talanta 2004, 64, 949–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casparini, G.M.; Grossi, G. Application of N,N-dialkyl aliphatic amides in the separation of some actinides. Sep. Sci. Technol. 1980, 15, 825–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaros, S.W.; Guedes da Silva, M.F.C.; Król, J.; Conceição Oliveira, M.; Smolenński, P.; Pombeiro, A.J.; Kirillov, A.M. Bioactive silver–organic networks assembled from 1,3,5-triaza-7-phosphaadamantane and flexible cyclohexanecarboxylate blocks. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 1486–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaros, S.W.; Guedes da Silva, M.F.C.; Florek, M.; Smoleński, P.; Pombeiro, A.J.; Kirillov, A.M. Silver (I) 1,3,5-triaza-7-phosphaadamantane coordination polymers driven by substituted glutarate and malonate building blocks: Self-assembly synthesis, structural features, and antimicrobial properties. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 5886–5894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smoleński, P.; Jaros, S.W.; Pettinari, C.; Lupidi, G.; Quassinti, L.; Bramucci, M.; Vitali, L.A.; Petrelli, D.; Kochel, A.; Kirillov, A.M. New water-soluble polypyridine silver (I) derivatives of 1,3,5-triaza-7-phosphaadamantane (PTA) with significant antimicrobial and antiproliferative activities. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 6572–6581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirillov, A.M.; Wieczorek, S.W.; Lis, A.; Guedes da Silva, M.F.C.; Florek, M.; Król, J.; Staroniewicz, Z.; Smoleński, P.; Pombeiro, A.J. 1,3,5-Triaza-7-phosphaadamantane-7-oxide (PTA=O): New diamondoid building block for design of three-dimensional metal–organic frameworks. Cryst. Growth Des. 2011, 11, 2711–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaros, S.W.; Guedes da Silva, M.F.C.; Florek, M.; Oliveira, M.C.; Smoleński, P.; Pombeiro, A.J.; Kirillov, A.M. Aliphatic dicarboxylate directed assembly of silver (I) 1,3,5-triaza-7-phosphaadamantane coordination networks: Topological versatility and antimicrobial activity. Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 5408–5417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaros, S.W.; Smolenski, P.; da Silva, M.F.C.; Florek, M.; Król, J.; Staroniewicz, Z.; Pombeiro, A.J.L.; Kirillov, A.M. New silver BioMOFs driven by 1,3,5-triaza-7-phosphaadamantane-7-sulfide (PTA=S): Synthesis, topological analysis and antimicrobial activity. Cryst. Eng. Commun. 2013, 15, 8060–8064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, R.; Tallon, T.; Sheahan, A.M.; Curran, R.; McCann, M.; Kavanagh, K.; Devereux, M.; McKee, V. ‘Silver bullets’ in antimicrobial chemotherapy: Synthesis, characterisation and biological screening of some new Ag (I)-containing imidazole complexes. Polyhedron 2006, 25, 1771–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klasen, H.J. Historical review of the use of silver in the treatment of burns. I. Early uses. Burns 2000, 26, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Youssef, M.A.; Langer, V.; Öhrström, L. Synthesis, a case of isostructural packing, and antimicrobial activity of silver (I) quinoxaline nitrate, silver (I)(2,5-dimethylpyrazine) nitrate and two related silver aminopyridine compounds. Dalton Trans. 2006, 21, 2542–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Youssef, M.A.; Langer, V.; Öhrström, L. A unique example of a high symmetry three-and four-connected hydrogen bonded 3D-network. Chem. Commun. 2006, 10, 1082–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Youssef, M.A.; Dey, R.; Gohar, Y.; Massoud, A.A.A.; Öhrström, L.; Langer, V. Synthesis and structure of silver complexes with nicotinate-type ligands having antibacterial activities against clinically isolated antibiotic resistant pathogens. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 5893–5903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massoud, A.A.A.; Langer, V.; Abu-Youssef, M.A. Bis [4-(dimethylamino) pyridine-κN1] silver (I) nitrate dihydrate. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Cryst. Struct. Commun. 2009, 65, m352–m354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Youssef, M.A.; Soliman, S.M.; Langer, V.; Gohar, Y.M.; Hasanen, A.A.; Makhyoun, M.A.; Zaky, A.H.; Öhrström, L.R. Synthesis, crystal structure, quantum chemical calculations, DNA interactions, and antimicrobial activity of [Ag(2-amino-3-methylpyridine) 2] NO3 and [Ag(pyridine-2-carboxaldoxime) NO3]. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 9788–9797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshima’a, A.M.; Gohar, Y.M.; Langer, V.; Lincoln, P.; Svensson, F.R.; Jänis, J.; Gårdebjer, S.T.; Haukka, M.; Jonsson, F.; Aneheim, E.; et al. Bis 4,5-diazafluoren-9-one silver (I) nitrate: Synthesis, X-ray structures, solution chemistry, hydrogel loading, DNA coupling and anti-bacterial screening. New J. Chem. 2011, 35, 640–648. [Google Scholar]

- Soliman, S.M.; Elsilk, S.E. Synthesis, structural analyses and antimicrobial activity of the water soluble 1D coordination polymer [Ag (3-aminopyridine)] ClO4. J. Mol. Struct. 2017, 1149, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshima’a, A.M.; Langer, V.; Gohar, Y.M.; Abu-Youssef, M.A.; Jänis, J.; Öhrström, L. 2D Bipyrimidine silver (I) nitrate: Synthesis, X-ray structure, solution chemistry and anti-microbial activity. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2011, 14, 550–553. [Google Scholar]

- Soliman, S.M.; Mabkhot, Y.N.; Barakat, A.; Ghabbour, H.A. A highly distorted hexacoordinated silver (I) complex: Synthesis, crystal structure, and DFT studies. J. Coord. Chem. 2017, 70, 1339–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spackman, M.A.; McKinnon, J.J. Fingerprinting intermolecular interactions in molecular crystals. CrystEngComm 2002, 4, 378–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayatilaka, D.; McKinnon, J.J.; Spackman, M.A. Towards quantitative analysis of intermolecular interactions with Hirshfeld surfaces. Chem. Commun. 2007, 3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spackman, M.A.; Jayatilaka, D. Hirshfeld surface analysis. CrystEngComm 2009, 11, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshfeld, F.L. Bonded-atom fragments for describing molecular charge densities. Theor. Chim. Acta 1977, 44, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowsky, S.; Dean, P.M.; Skelton, B.W.; Sobolev, A.N.; Spackman, M.A.; White, A.H. Crystal packing in the 2-R, 4-oxo-[1,3-a/b]-naphthodioxanes–Hirshfeld surface analysis and melting point correlation. CrystEngComm 2012, 14, 1083–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, R.F.; Essén, H. The characterization of atomic interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 1984, 80, 1943–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, E.; Alkorta, I.; Elguero, J.; Molins, E. From weak to strong interactions: A comprehensive analysis of the topological and energetic properties of the electron density distribution involving X–H…F–Y systems. J. Chem. Phys. 2002, 117, 5529–5542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, E.; Molins, E.; Lecomte, C. Hydrogen bond strengths revealed by topological analyses of experimentally observed electron densities. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1998, 285, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, J.E.; Weinhold, F. Analysis of the geometry of the hydroxymethyl radical by the “different hybrids for different spins” natural bond orbital procedure. J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM. 1988, 169, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ok, K.M.; Halasyamani, P.S.; Casanova, D.; Llunell, M.; Alemany, P.; Alvarez, S. Distortions in octahedrally coordinated d0 transition metal oxides: A continuous symmetry measures approach. Chem. Mater. 2006, 18, 3176–3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becke, A.D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.D.; Head-Gordon, M. Long-range corrected hybrid density functionals with damped atom–atom dispersion corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 6615–6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rassolov, V.A.; Pople, J.A.; Ratner, M.A.; Windus, T.L. 6-31G* basis set for atoms K through Zn. J. Chem. Phys. 1998, 109, 1223–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, P.J.; Wadt, W.R. Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for K to Au including the outermost core orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 82, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basis Set Exchange. Available online: https://bse.pnl.gov/bse/portal (accessed on 20 January 2018).

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A. Gaussian 09, Revision A.02; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dennington, R., II; Keith, T.; Millam, J. GaussView; Version 4.1; Semichem Inc.: Shawnee Mission, KS, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bader, R.F.W. Atoms in Molecules: A Quantum Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wave function analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glendening, E.D.; Reed, A.E.; Carpenter, J.E.; Weinhold, F. NBO; Version 3.1; University of Wisconsin: Madison, CI, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick, G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Found. Crystallogr. 2008, 64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruker. APEX2, SAINT and SADABS; Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, S.K.; Grimwood, D.J.; McKinnon, J.J.; Turner, M.J.; Jayatilaka, D.; Spackman, M.A. Crystal Explorer; Version 3.1; University of Western Australia: Crawley, WA, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Sample Availability: Samples of the compound [AgL(NO3)]2.H2O complex is available from the authors. |

| Parameters | [AgL(NO3)]2.H2O] |

|---|---|

| F.wt. | C56H48Ag2Cl2N10O13 |

| M.wt. | 1355.68 |

| T | 293(2) K |

| λ (Mo Kα radiation) | 0.71073 Å |

| Crystal system | Tetragonal |

| Space group | I41/a |

| Unit cell dimensions | a = 21.1544 (11) Åc = 25.2931 (9) Å |

| Volume | 11318.9 (12) Å3 |

| R-Factor | 0.153 |

| Z | 8 |

| Density (calculated) | 1.589 mg m−3 |

| Absorption coefficient | 0.86 mm−1 |

| F(000) | 5472 |

| Crystal size | 0.29 × 0.20 × 0.16 mm |

| Theta range for data collection | 2.3–21.5° |

| Completeness to θ = 21.5° | 99.9 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.06 |

| Diffractometer | Bruker APEX-II D8 Venture diffractometer |

| Absorption correction | Multi-scan, SADABS |

| Limiting indices | −27 ≤ h ≤ 27, −27 ≤ k ≤ 27, −32 ≤ l ≤ 32 |

| Reflections collected/unique | 77356/3477 [R(int) = 0.153] |

| Refinement method | Full-matrix least-squares on F2 |

| Data/restraints/parameters | 6500/0/2375 |

| Final R indices [I > 2σ(I)] | R1 = 0.070, wR2 = 0.151 |

| R indices (all data) | R1 = 0.152, wR2 = 0.190 |

| Largest diff. peak and hole (e A−3) | 0.83 and −0.73 |

| CCDC number | 1543617 |

| Ag1—O6 | 2.541 (5) | O6—N5 | 1.247 (6) |

| Ag1—N4 | 2.224 (4) | N1—C1 | 1.348 (9) |

| Ag1—N1i | 2.221 (5) | N1—C5 | 1.342 (8) |

| Cl1—C18 | 1.755 (7) | N2—C5 | 1.404 (7) |

| O1—C6 | 1.209 (7) | N2—C6 | 1.363 (8) |

| O2—C8 | 1.219 (8) | N3—C8 | 1.337 (7) |

| O3—C22 | 1.203 (9) | N3—C9 | 1.390 (6) |

| O4—N5 | 1.218 (7) | N4—C9 | 1.340 (7) |

| O5—N5 | 1.236 (7) | N4—C13 | 1.333 (8) |

| O6—Ag1—N4 | 101.67 (16) | N1—C5—N2 | 115.3 (5) |

| O6—Ag1—N1i | 102.63 (16) | N1—C5—C4 | 121.9 (6) |

| N1i—Ag1—N4 | 152.93 (18) | O1—C6—C7 | 122.0 (5) |

| Ag1—O6—N5 | 115.2 (3) | N2—C6—C7 | 114.6 (5) |

| C1—N1—C5 | 117.3 (5) | O1—C6—N2 | 123.3 (5) |

| Ag1i—N1—C1 | 111.7 (4) | O2—C8—C7 | 120.5 (5) |

| Ag1i—N1—C5 | 130.9 (4) | N3—C8—C7 | 115.8 (5) |

| C5—N2—C6 | 127.5 (5) | O2—C8—N3 | 123.7 (5) |

| C8—N3—C9 | 128.1 (5) | N3—C9—N4 | 115.2 (5) |

| Ag1—N4—C9 | 127.3 (3) | N4—C9—C10 | 120.9 (5) |

| Ag1—N4—C13 | 114.3 (4) | N3—C9—C10 | 123.9 (5) |

| C9—N4—C13 | 118.2 (5) | N4—C13—C12 | 123.9 (7) |

| O4—N5—O5 | 122.1 (5) | Cl1—C18—C17 | 120.1 (5) |

| O4—N5—O6 | 118.4 (5) | Cl1—C18—C19 | 118.8 (6) |

| O5—N5—O6 | 119.4 (5) | O3—C22—C23 | 121.2 (6) |

| N1—C1—C2 | 123.7 (6) | O3—C22—C21 | 120.8 (6) |

| N2—C5—C4 | 122.7 (6) |

| D—H···A | D—H (Å) | H…A (Å) | D…A (Å) | D—H…A (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N2—H2B…O5 | 0.8600 | 2.2300 | 3.044 (7) | 158.00 |

| N3—H3B…O6 | 0.8600 | 2.0800 | 2.923 (6) | 167.00 |

| C2—H2A…O4i | 0.9300 | 2.4900 | 3.358 (11) | 155.00 |

| C4—H4A…O1 | 0.9300 | 2.2000 | 2.806 (8) | 123.00 |

| C4—H4A…O6ii | 0.9300 | 2.3600 | 3.160 (8) | 144.00 |

| C7—H7A…O6 | 0.9800 | 2.4800 | 3.349 (7) | 148.00 |

| Atom | L | [AgL(NO3)]2·H2O | Atom | L | [AgL(NO3)]2·H2O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1A | 8.34 | 8.33 | H19A | 7.57 | 7.56 |

| H2A | 7.14 | 7.15 | H20A | 7.44 | 7.43 |

| H3A | 7.86 | 7.83 | H21A | 3.24 | 3.26 |

| H4A | 8.24 | 8.24 | H21B | 3.66–3.70 | 3.71–3.78 |

| H7A | 4.15–4.28 | 4.18 | H24A | 8.08 | 8.04 |

| H10A | 8.24 | 8.24 | H25A | 7.68 | 7.68 |

| H11A | 7.86 | 7.83 | H26A | 7.80 | 7.75 |

| H12A | 7.14 | 7.15 | H27A | 7.68 | 7.68 |

| H13A | 8.34 | 8.33 | H28A | 8.08 | 8.04 |

| H16A | 7.44 | 7.43 | HN2 | 10.56 | 10.48 |

| H17A | 7.57 | 7.56 | HN3 | 10.65 | 10.62 |

| Bond | Distance Å | ρ(r) a.u. | G(r) a.u. | V(r) a.u. | H(r) a.u. | |V(r)|/G(r) a | Eint Kcal/mol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | |||||||

| Ag—O6 | 2.541 | 0.0222 | 0.0210 | −0.0199 | 0.0010 | 0.9514 | 6.2554 |

| Ag—O5 | 2.720 | 0.0318 | 0.0346 | −0.0337 | 0.0009 | 0.9748 | 10.5845 |

| Ag—N1i | 2.221 | 0.0708 | 0.0858 | −0.0980 | −0.0122 | 1.1419 | 30.7522 |

| Ag—N4 | 2.224 | 0.0703 | 0.0854 | −0.0974 | −0.0119 | 1.1399 | 30.5452 |

| WB97XD | |||||||

| Ag—O6 | 2.539 | 0.0220 | 0.0211 | −0.0201 | 0.0010 | 0.9529 | 6.2978 |

| Ag—O5 | 2.720 | 0.0315 | 0.0348 | −0.0339 | 0.0009 | 0.9746 | 10.6384 |

| Ag—N1i | 2.221 | 0.0706 | 0.0869 | −0.0989 | −0.0120 | 1.1385 | 31.0405 |

| Ag—N4 | 2.222 | 0.0701 | 0.0864 | −0.0982 | −0.0118 | 1.1365 | 30.8184 |

| NBOi | NBOj | B3LYP | WB97XD |

|---|---|---|---|

| LP(1)N1i | LP * (6)Ag | 33.56 | 39.38 |

| LP(1)N1i | LP * (7)Ag | 10.54 | 13.42 |

| Net | 44.10 | 52.80 | |

| LP(1)N4 | LP * (6)Ag | 32.19 | 37.78 |

| LP(1)N4 | LP * (7)Ag | 10.72 | 13.53 |

| Net | 42.91 | 51.31 | |

| LP(1)O6 | LP * (6)Ag | 3.78 | 4.31 |

| LP(1)O6 | LP * (8)Ag | 8.90 | 9.53 |

| LP(2)O6 | LP * (6)Ag | 9.54 | 11.40 |

| LP(2)O6 | LP * (8)Ag | 10.76 | 12.18 |

| Net | 32.98 | 37.4 | |

| LP(1)O5 | LP * (6)Ag | 3.27 | 4.08 |

| LP(1)O5 | LP * (9)Ag | 8.59 | 9.94 |

| LP(2)O5 | LP * (6)Ag | 3.61 | 4.27 |

| LP(2)O5 | LP * (9)Ag | 4.64 | 5.40 |

| Net | 20.11 | 23.7 | |

| NBO | [AgL(NO3)]2 | Free Species | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occup. | Energy | Occup. | Energy | |

| B3LYP | ||||

| LP(1)N1 | 1.8252 | −0.4110 | 1.9211 | −0.3478 |

| LP(1)N1 | 1.8276 | −0.4131 | 1.9211 | −0.3518 |

| LP(1)O6 | 1.9578 | −0.6832 | 1.9850 | −0.5378 |

| LP(2)O6 | 1.8922 | −0.3633 | 1.9087 | −0.0441 |

| LP(1)O5 | 1.9603 | −0.7380 | 1.9856 | −0.5423 |

| LP(2)O5 | 1.8957 | −0.2981 | 1.9155 | −0.0406 |

| LP * (6)Ag | 0.2571 | 0.0119 | 0.0000 | 45.8839 |

| LP * (7)Ag | 0.0693 | 0.2325 | 0.0000 | −0.1125 |

| LP * (8)Ag | 0.0603 | 0.1036 | 0.0000 | 0.5923 |

| LP * (9)Ag | 0.0494 | 0.0874 | 0.0000 | 3.0170 |

| WB97XD | ||||

| LP(1)N1 | 1.8356 | −0.4848 | 1.9245 | −0.4290 |

| LP(1)N1 | 1.8377 | −0.4872 | 1.9244 | −0.4331 |

| LP(1)O6 | 1.9579 | −0.7686 | 1.9853 | −0.6334 |

| LP(2)O6 | 1.8964 | −0.4460 | 1.9103 | −0.1259 |

| LP(1)O5 | 1.9605 | −0.8279 | 1.9859 | −0.6378 |

| LP(2)O5 | 1.8991 | −0.3769 | 1.9169 | −0.1227 |

| LP * (6)Ag | 0.2329 | 0.0808 | 0.0000 | 0.7750 |

| LP * (7)Ag | 0.0706 | 0.3025 | 0.0000 | 36.4326 |

| LP * (8)Ag | 0.0586 | 0.1721 | 0.0000 | 13.2220 |

| LP * (9)Ag | 0.0471 | 0.1535 | 0.0000 | −0.0243 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soliman, S.M.; Barakat, A.; Islam, M.S.; Ghabbour, H.A. Synthesis, Crystal Structure and DFT Studies of a New Dinuclear Ag(I)-Malonamide Complex. Molecules 2018, 23, 888. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/molecules23040888

Soliman SM, Barakat A, Islam MS, Ghabbour HA. Synthesis, Crystal Structure and DFT Studies of a New Dinuclear Ag(I)-Malonamide Complex. Molecules. 2018; 23(4):888. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/molecules23040888

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoliman, Saied M., Assem Barakat, Mohammad Shahidul Islam, and Hazem A. Ghabbour. 2018. "Synthesis, Crystal Structure and DFT Studies of a New Dinuclear Ag(I)-Malonamide Complex" Molecules 23, no. 4: 888. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/molecules23040888