Key Applications and Potential Limitations of Ionic Liquid Membranes in the Gas Separation Process of CO2, CH4, N2, H2 or Mixtures of These Gases from Various Gas Streams

Abstract

:1. Introduction

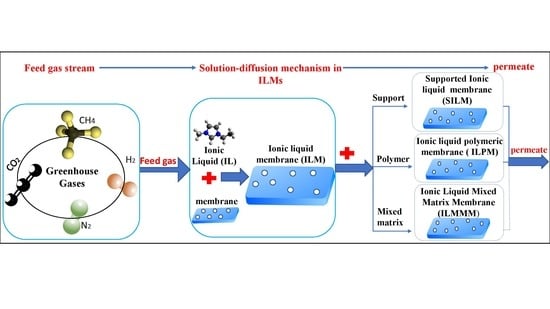

2. Global Warming

3. Ionic Liquid Membranes (ILMs) in Gas Separation Processes

3.1. Ionic Liquids

3.1.1. Selected Physicochemical Properties of Ionic Liquids

3.1.2. Melting Point

3.1.3. Viscosity

3.1.4. Vapour Pressure and Thermal Stability

3.2. Supported Ionic Liquid Membranes (SILMs)

3.3. Ionic Liquid Polymeric Membranes (ILPMs)

3.4. Ionic Liquid Mixed Matrix Membranes (ILMMMs)

3.5. Comparison Between SILMs, PILMs, and ILMMMs

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pratibha, G.; Srinivas, I.; Rao, K.V.; Shanker, A.K.; Raju, B.M.K.; Choudhary, D.K.; Srinivas Rao, K.; Srinivasarao, C.; Maheswari, M. Net global warming potential and greenhouse gas intensity of conventional and conservation agriculture system in rainfed semi arid tropics of India. Atmos. Environ. 2016, 145, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skytt, T.; Nielsen, S.N.; Jonsson, B.-G. Global warming potential and absolute global temperature change potential from carbon dioxide and methane fluxes as indicators of regional sustainability—A case study of Jämtland, Sweden. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 110, 105831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholy, J.; Pongrácz, R. A brief review of health-related issues occurring in urban areas related to global warming of 1.5 °C. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 30, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mika, J.; Forgo, P.; Lakatos, L.; Olah, A.B.; Rapi, S.; Utasi, Z. Impact of 1.5K global warming on urban air pollution and heat island with outlook on human health effects. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 30, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tang, L.; Qiu, X.; Liu, B.; Chang, X.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Cao, W.; Zhu, Y. Impacts of 1.5 and 2.0 °C global warming on rice production across China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 284, 107900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Liu, J.; Leung, F. A framework to quantify impacts of elevated CO2 concentration, global warming and leaf area changes on seasonal variations of water resources on a river basin scale. J. Hydrol. 2019, 570, 508–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordell, B. Thermal pollution causes global warming. Glob. Planet. Chang. 2003, 38, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesiri, B.; Liu, A.; Goonetilleke, A. Impact of global warming on urban stormwater quality: From the perspective of an alternative water resource. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Song, C.; Miller, B.G.; Scaroni, A.W. Adsorption separation of carbon dioxide from flue gas of natural gas-fired boiler by a novel nanoporous “molecular basket” adsorbent. Fuel Process. Technol. 2005, 86, 1457–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.L.; Feldkirchner, H.L.; Stern, S.A.; Houde, A.Y.; Gamez, J.P.; Meyer, H.S. Field tests of membrane modules for the separation of carbon dioxide from low-quality natural gas. Gas. Sep. Purif. 1995, 9, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufford, T.E.; Smart, S.; Watson, G.C.Y.; Graham, B.F.; Boxall, J.; Diniz da Costa, J.C.; May, E.F. The removal of CO2 and N2 from natural gas: A review of conventional and emerging process technologies. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2006, 94–95, 123–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez, M.; Ortiz, A.; Gorri, D.; Ortiz, I. Comparative performance of commercial polymeric membranes in the recovery of industrial hydrogen waste gas streams. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasikumar, B.; Arthanareeswaran, G.; Ismail, A.F. Recent progress in ionic liquid membranes for gas separation. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 266, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadgouda, S.G.; Kathe, M.V.; Fan, L.-S. Cold gas efficiency enhancement in a chemical looping combustion system using staged H2 separation approach. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2017, 42, 4751–4763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Swift, J.; Zhang, Q.; Fan, L.-S.; Tong, A. Biogas to H2 conversion with CO2 capture using chemical looping technology: Process simulation and comparison to conventional reforming processes. Fuel 2020, 279, 118479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, M.; Jin, B.; Ma, J.; Zou, X.; Wang, X.; Zheng, C.; Zhao, H. Thermodynamic and economic performance of oxy-combustion power plants integrating chemical looping air separation. Energy 2020, 206, 118136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.N.; Chiesa, P.; Cloete, S.; Amini, S. Integration of chemical looping combustion for cost-effective CO2 capture from state-of-the-art natural gas combined cycles. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2020, 7, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculescu, A.E.; Bornea, A.; Ana, G.; Zamfirache, M. Development of specific software for hydrogen isotopes separation by cryogenic distillation of ICSI Pilot Plant. Fusion Eng. Des. 2020, 158, 111642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigagão, G.V.; de Medeiros, J.L.; de Araújo, O.Q.F. A novel cryogenic vapor-recompression air separation unit integrated to oxyfuel combined-cycle gas-to-wire plant with carbon dioxide enhanced oil recovery: Energy and economic assessments. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 189, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, A.M.; El-Maghlany, W.M.; Eldrainy, Y.A.; Attia, A. New approach for biogas purification using cryogenic separation and distillation process for CO2 capture. Energy 2018, 156, 328–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, M.; Jobson, M.; Smith, R. Membrane–cryogenic Distillation Hybrid Processes for Cost-effective Argon Production from Air. In Computer Aided Chemical Engineering; Espuña, A., Graells, M., Puigjaner, L., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 40, pp. 1117–1122. [Google Scholar]

- Fried, J.R. Basic Principles of Membrane Technology by Marcel Mulder (University of Twente, The Netherlands); Kluwer Academic: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1996; 564p, ISBN 0-7823-4247-X. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo, P.; Drioli, E.; Golemme, G. Membrane Gas Separation: A Review/State of the Art. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 4638–4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa Gomes, M.F.; Husson, P. Ionic Liquids: Promising Media for Gas Separations. In Ionic Liquids: From Knowledge to Application; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; Volume 1030, pp. 223–237. [Google Scholar]

- Zia ul Mustafa, M.; bin Mukhtar, H.; Md Nordin, N.A.H.; Mannan, H.A.; Nasir, R.; Fazil, N. Recent Developments and Applications of Ionic Liquids in Gas Separation Membranes. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2019, 42, 2580–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morice, C.P.; Kennedy, J.J.; Rayner, N.A.; Jones, P.D. Quantifying uncertainties in global and regional temperature change using an ensemble of observational estimates: The HadCRUT4 data set. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2012, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallett, J.P.; Welton, T. Room-Temperature Ionic Liquids: Solvents for Synthesis and Catalysis. 2. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 3508–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, M.; Coronas, A.; García, J.; Salgado, J. Thermal Stability of Ionic Liquids for Their Application as New Absorbents. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 15718–15727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Mu, T. Comprehensive Investigation on the Thermal Stability of 66 Ionic Liquids by Thermogravimetric Analysis. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 8651–8664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wang, M.; Cheng, Z.-M. Thermal Stability and Vapor–Liquid Equilibrium for Imidazolium Ionic Liquids as Alternative Reaction Media. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2015, 60, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Ma, W.; Theyssen, N.; Chen, C.; Hou, Z. Temperature-Responsive Ionic Liquids: Fundamental Behaviors and Catalytic Applications. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 6881–6928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Chen, L.; Ye, Y.; Chen, L.; Qi, Z.; Freund, H.; Sundmacher, K. An Overview of Mutual Solubility of Ionic Liquids and Water Predicted by COSMO-RS. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 6256–6264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrey, J.D.; Rogers, R.D. Green Industrial Applications of Ionic Liquids: Technology Review. In Ionic Liquids; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; Volume 818, pp. 446–458. [Google Scholar]

- Wishart, J.F. Radiation and Radical Chemistry of Ionic Liquids for Energy Applications. In Ionic Liquids: Current State and Future Directions; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Volume 1250, pp. 251–272. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrey, J.D.; Turner, M.B.; Rogers, R.D. Selection of Ionic Liquids for Green Chemical Applications. In Ionic Liquids as Green Solvents; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; Volume 856, pp. 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, N.J.; Lye, G.J. Application of Room-Temperature Ionic Liquids in Biocatalysis: Opportunities and Challenges. In Ionic Liquids; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; Volume 818, pp. 347–359. [Google Scholar]

- Isosaari, P.; Srivastava, V.; Sillanpää, M. Ionic liquid-based water treatment technologies for organic pollutants: Current status and future prospects of ionic liquid mediated technologies. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 690, 604–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinkowska, R.; Konieczna, K.; Marcinkowski, Ł.; Namieśnik, J.; Kloskowski, A. Application of ionic liquids in microextraction techniques: Current trends and future perspectives. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 119, 115614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthod, A.; Ruiz-Ángel, M.J.; Carda-Broch, S. Recent advances on ionic liquid uses in separation techniques. J. Chromatogr. A 2018, 1559, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacy, E.W.; Gainaru, C.P.; Gobet, M.; Wojnarowska, Z.; Bocharova, V.; Greenbaum, S.G.; Sokolov, A.P. Fundamental Limitations of Ionic Conductivity in Polymerized Ionic Liquids. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 8637–8645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad Adlie, S. Ionic liquids: Preparations and limitations. Makara J. Sci. 2011, 14, 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, C.F.; Neves, L.A.; Chagas, R.; Ferreira, L.M.; Afonso, C.A.M.; Crespo, J.G.; Coelhoso, I.M. CO2 removal from anaesthesia circuits using gas-ionic liquid membrane contactors. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamair, Z.; Habib, N.; Gilani, M.A.; Khan, A.L. Theoretical and experimental investigation of CO2 separation from CH4 and N2 through supported ionic liquid membranes. Appl. Energy 2020, 268, 115016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohaib, Q.; Vadillo, J.M.; Gómez-Coma, L.; Albo, J.; Druon-Bocquet, S.; Irabien, A.; Sanchez-Marcano, J. CO2 capture with room temperature ionic liquids; coupled absorption/desorption and single module absorption in membrane contactor. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2020, 223, 115719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia-ul-Mustafa, M.; Mukhtar, H.; Nordin, N.; Mannan, H.A. Effect of imidazolium based ionic liquids on PES membrane for CO2/CH4 separation. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 16, 1976–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabais, A.R.; Martins, A.P.S.; Alves, V.D.; Crespo, J.G.; Marrucho, I.M.; Tomé, L.C.; Neves, L.A. Poly(ionic liquid)-based engineered mixed matrix membranes for CO2/H2 separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 222, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Liu, Q.-S.; Wang, P.-P.; Welz-Biermann, U.; Yang, J.-Z. Surface Tension and Density of Ionic Liquid n-Butylpyridinium Heptachlorodialuminate. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2011, 56, 3722–3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhu, N.; Bai, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhou, H.; Wu, C. Highly Safe Ionic Liquid Electrolytes for Sodium-Ion Battery: Wide Electrochemical Window and Good Thermal Stability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 21381–21386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Mahony, A.M.; Silvester, D.S.; Aldous, L.; Hardacre, C.; Compton, R.G. Effect of Water on the Electrochemical Window and Potential Limits of Room-Temperature Ionic Liquids. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2008, 53, 2884–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, N.; Imakura, S.; Kakiuchi, T. Wide Electrochemical Window at the Interface between Water and a Hydrophobic Room-Temperature Ionic Liquid of Tetrakis[3,5-bis(Trifluoromethyl)phenyl]borate. Anal. Chem. 2006, 78, 2726–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plechkova, N.V.; Seddon, K.R. Applications of ionic liquids in the chemical industry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 123–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Lu, X.; Zhang, S.; Guo, L. Physicochemical Properties of Ionic Liquids. In Ionic Liquids Further UnCOILed; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 275–307. [Google Scholar]

- García, G.; Atilhan, M.; Aparicio, S. Viscous origin of ionic liquids at the molecular level: A quantum chemical insight. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2014, 610–611, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasirpour, N.; Mohammadpourfard, M.; Zeinali Heris, S. Ionic liquids: Promising compounds for sustainable chemical processes and applications. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2020, 160, 264–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paduszyński, K.; Domańska, U. Viscosity of Ionic Liquids: An Extensive Database and a New Group Contribution Model Based on a Feed-Forward Artificial Neural Network. J. Chem. Inf. Modeling 2014, 54, 1311–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerome, F.S.; Tseng, J.T.; Fan, L.T. Viscosities of aqueous glycol solutions. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1968, 13, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lorenzi, L.; Fermeglia, M.; Torriano, G. Density, Refractive Index, and Kinematic Viscosity of Diesters and Triesters. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1997, 42, 919–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiGuilio, R.M.; Lee, R.J.; Schaeffer, S.T.; Brasher, L.L.; Teja, A.S. Densities and viscosities of the ethanolamines. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1992, 37, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Zhao, D.; Wen, L.; Yang, S.; Chen, X. Viscosity of ionic liquids: Database, observation, and quantitative structure-property relationship analysis. AIChE J. 2012, 58, 2885–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrenberg, M.; Beck, M.; Neise, C.; Keßler, O.; Kragl, U.; Verevkin, S.P.; Schick, C. Vapor pressure of ionic liquids at low temperatures from AC-chip-calorimetry. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 21381–21390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maton, C.; De Vos, N.; Stevens, C.V. Ionic liquid thermal stabilities: Decomposition mechanisms and analysis tools. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 5963–5977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Qin, L.; Jiang, J.; Mu, T.; Gao, G. Thermal, electrochemical and radiolytic stabilities of ionic liquids. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 8382–8402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cserjési, P.; Nemestóthy, N.; Bélafi-Bakó, K. Gas separation properties of supported liquid membranes prepared with unconventional ionic liquids. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 349, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, R.; Appleby, J.B.; Pez, G.P. New facilitated transport membranes for the separation of carbon dioxide from hydrogen and methane. J. Membr. Sci. 1995, 104, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scovazzo, P.; Visser, A.E.; Davis, J.H.; Rogers, R.D.; Koval, C.A.; DuBois, D.L.; Noble, R.D. Supported Ionic Liquid Membranes and Facilitated Ionic Liquid Membranes. In Ionic Liquids; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; Volume 818, pp. 69–87. [Google Scholar]

- Scovazzo, P. Determination of the upper limits, benchmarks, and critical properties for gas separations using stabilized room temperature ionic liquid membranes (SILMs) for the purpose of guiding future research. J. Membr. Sci. 2009, 343, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, N.A.; Hashim, N.A.; Aroua, M.K. Supported ionic liquid membranes (SILMs) as a contactor for selective absorption of CO2/O2 by aqueous monoethanolamine (MEA). Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 230, 115849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, J.A.; Do-Thanh, C.-L.; Mahurin, S.M.; Tian, Z.; Onishi, N.C.; Jiang, D.-E.; Dai, S. Supported bicyclic amidine ionic liquids as a potential CO2/N2 separation medium. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 565, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Asadollahzadeh, M.; Shirazian, S. Molecular-level understanding of supported ionic liquid membranes for gas separation. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 262, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karousos, D.S.; Labropoulos, A.I.; Tzialla, O.; Papadokostaki, K.; Gjoka, M.; Stefanopoulos, K.L.; Beltsios, K.G.; Iliev, B.; Schubert, T.J.S.; Romanos, G.E. Effect of a cyclic heating process on the CO2/N2 separation performance and structure of a ceramic nanoporous membrane supporting the ionic liquid 1-methyl-3-octylimidazolium tricyanomethanide. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 200, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-I.; Kim, B.-S.; Byun, Y.-H.; Lee, S.-H.; Lee, E.-W.; Lee, J.-M. Preparation of supported ionic liquid membranes (SILMs) for the removal of acidic gases from crude natural gas. Desalination 2009, 236, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E.; Albo, J.; Irabien, A. Acetate based Supported Ionic Liquid Membranes (SILMs) for CO2 separation: Influence of the temperature. J. Membr. Sci. 2014, 452, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis, P.; Neves, L.A.; Afonso, C.A.M.; Coelhoso, I.M.; Crespo, J.G.; Garea, A.; Irabien, A. Facilitated transport of CO2 and SO2 through Supported Ionic Liquid Membranes (SILMs). Desalination 2009, 245, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, C.; Li, L.; Qin, W.; Xu, A. CO2 separation by supported ionic liquid membranes and prediction of separation performance. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2016, 53, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T.; Xie, W.; Ji, X.; Liu, C.; Feng, X.; Lu, X. CO2/N2 separation using supported ionic liquid membranes with green and cost-effective [Choline][Pro]/PEG200 mixtures. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2016, 24, 1513–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tu, Z.; Li, H.; Huang, K.; Hu, X.; Wu, Y.; MacFarlane, D.R. Selective separation of H2S and CO2 from CH4 by supported ionic liquid membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 543, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Close, J.J.; Farmer, K.; Moganty, S.S.; Baltus, R.E. CO2/N2 separations using nanoporous alumina-supported ionic liquid membranes: Effect of the support on separation performance. J. Membr. Sci. 2012, 390–391, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xiong, W.; Tu, Z.; Peng, L.; Wu, Y.; Hu, X. Supported Ionic Liquid Membranes with Dual-Site Interaction Mechanism for Efficient Separation of CO2. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 10792–10799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojniak, S.D.; Khan, A.L.; Hollóczki, O.; Kirchner, B.; Vankelecom, I.F.J.; Dehaen, W.; Binnemans, K. Separation of Carbon Dioxide from Nitrogen or Methane by Supported Ionic Liquid Membranes (SILMs): Influence of the Cation Charge of the Ionic Liquid. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 15131–15140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Yan, W.; Wang, J.; Ding, H.; Yu, Y. Absorption of CO2 with supported imidazolium-based ionic liquid membranes. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2015, 90, 1537–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J.C.; Friess, K.; Clarizia, G.; Schauer, J.; Izák, P. High Ionic Liquid Content Polymeric Gel Membranes: Preparation and Performance. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, H.; Wang, J.; Abdeltawab, A.A.; Chen, X.; Yu, G.; Yu, Y. Synthesis of polymeric ionic liquids material and application in CO2 adsorption. J. Energy Chem. 2017, 26, 909–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shaligram, S.V.; Wadgaonkar, P.P.; Kharul, U.K. Polybenzimidazole-based polymeric ionic liquids (PILs): Effects of ‘substitution asymmetry’ on CO2 permeation properties. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 493, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavsar, R.S.; Kumbharkar, S.C.; Kharul, U.K. Polymeric ionic liquids (PILs): Effect of anion variation on their CO2 sorption. J. Membr. Sci. 2012, 389, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, S.; Sarwar, M.I.; Mecerreyes, D. Polymeric ionic liquids for CO2 capture and separation: Potential, progress and challenges. Polym. Chem. 2015, 6, 6435–6451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tomé, L.C.; Aboudzadeh, M.A.; Rebelo, L.P.N.; Freire, C.S.R.; Mecerreyes, D.; Marrucho, I.M. Polymeric ionic liquids with mixtures of counter-anions: A new straightforward strategy for designing pyrrolidinium-based CO2 separation membranes. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 10403–10411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja Shahrom, M.S.; Wilfred, C.D.; Taha, A.K.Z. CO2 capture by task specific ionic liquids (TSILs) and polymerized ionic liquids (PILs and AAPILs). J. Mol. Liq. 2016, 219, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Anguille, S.; Bendahan, M.; Moulin, P. Ionic liquids combined with membrane separation processes: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 222, 230–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannan, H.A.; Mohshim, D.F.; Mukhtar, H.; Murugesan, T.; Man, Z.; Bustam, M.A. Synthesis, characterization, and CO2 separation performance of polyether sulfone/[EMIM][Tf2N] ionic liquid-polymeric membranes (ILPMs). J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2017, 54, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, W.; Gao, H.; Bai, Y.; Sun, Y.; Chen, Y. Synthesis and gas transport properties of poly(ionic liquid) based semi-interpenetrating polymer network membranes for CO2/N2 separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 528, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomé, L.C.; Mecerreyes, D.; Freire, C.S.R.; Rebelo, L.P.N.; Marrucho, I.M. Pyrrolidinium-based polymeric ionic liquid materials: New perspectives for CO2 separation membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2013, 428, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannan, H.A.; Mukhtar, H.; Shahrun, M.S.; Bustam, M.A.; Man, Z.; Bakar, M.Z.A. Effect of [EMIM][Tf2N] Ionic Liquid on Ionic Liquid-polymeric Membrane (ILPM) for CO2/CH4 Separation. Procedia Eng. 2016, 148, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liang, L.; Gan, Q.; Nancarrow, P. Composite ionic liquid and polymer membranes for gas separation at elevated temperatures. J. Membr. Sci. 2014, 450, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomé, L.C.; Gouveia, A.S.L.; Freire, C.S.R.; Mecerreyes, D.; Marrucho, I.M. Polymeric ionic liquid-based membranes: Influence of polycation variation on gas transport and CO2 selectivity properties. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 486, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mannan, H.A.; Mukhtar, H.; Murugesan, T.; Man, Z.; Bustam, M.A.; Shaharun, M.S.; Abu Bakar, M.Z. Prediction of CO2 gas permeability behavior of ionic liquid-polymer membranes (ILPM). J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasmeen, I.; Ilyas, A.; Shamair, Z.; Gilani, M.A.; Rafiq, S.; Bilad, M.R.; Khan, A.L. Synergistic effects of highly selective ionic liquid confined in nanocages: Exploiting the three component mixed matrix membranes for CO2 capture. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2020, 155, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, M.; Mandal, M.K. Synthesis and characterization of ionic liquid based mixed matrix membrane for acid gas separation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 156, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, A.; Muhammad, N.; Gilani, M.A.; Vankelecom, I.F.J.; Khan, A.L. Effect of zeolite surface modification with ionic liquid [APTMS][Ac] on gas separation performance of mixed matrix membranes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 205, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.N.R.; Leo, C.P.; Mohammad, A.W.; Ahmad, A.L. Modification of gas selective SAPO zeolites using imidazolium ionic liquid to develop polysulfone mixed matrix membrane for CO2 gas separation. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2017, 244, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohshim, D.F.; Mukhtar, H.; Man, Z. The effect of incorporating ionic liquid into polyethersulfone-SAPO34 based mixed matrix membrane on CO2 gas separation performance. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2014, 135, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, R.; Ahmad, N.N.R.; Mukhtar, H.; Mohshim, D.F. Effect of ionic liquid inclusion and amino–functionalized SAPO-34 on the performance of mixed matrix membranes for CO2/CH4 separation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 2363–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.N.R.; Leo, C.P.; Ahmad, A.L. Effects of solvent and ionic liquid properties on ionic liquid enhanced polysulfone/SAPO-34 mixed matrix membrane for CO2 removal. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2019, 283, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Isfahani, A.P.; Muchtar, A.; Sakurai, K.; Shrestha, B.B.; Qin, D.; Yamaguchi, D.; Sivaniah, E.; Ghalei, B. Pebax/ionic liquid modified graphene oxide mixed matrix membranes for enhanced CO2 capture. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 565, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, A.R.; Patel, C.M.; Murthy, Z.V.P. Polyethersulfone based MMMs with 2D materials and ionic liquid for CO2, N2 and CH4 separation. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 262, 110256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Z.V.; Cowan, M.G.; McDanel, W.M.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, R.; Gin, D.L.; Noble, R.D. Determination and optimization of factors affecting CO2/CH4 separation performance in poly(ionic liquid)-ionic liquid-zeolite mixed-matrix membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2016, 509, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudiono, Y.C.; Carlisle, T.K.; Bara, J.E.; Zhang, Y.; Gin, D.L.; Noble, R.D. A three-component mixed-matrix membrane with enhanced CO2 separation properties based on zeolites and ionic liquid materials. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 350, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudiono, Y.C.; Carlisle, T.K.; LaFrate, A.L.; Gin, D.L.; Noble, R.D. Novel mixed matrix membranes based on polymerizable room-temperature ionic liquids and SAPO-34 particles to improve CO2 separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 370, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Abbreviation | Name |

|---|---|

| ILM | Ionic Liquid Membrane |

| SILM | Supported Ionic Liquid Membrane |

| ILPM | Ionic Liquid Polymeric Membrane |

| ILMMM | Ionic Liquid Mixed Matrix Membrane |

| CILPMs | Composite Ionic Liquid and Polymer membranes |

| RTIL | Room Temperature Ionic Liquid |

| poly (RTIL) | Polymerizable room-temperature ionic liquids |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| N2 | Nitrogen |

| NOX | Nitrogen Oxides |

| SOX | Sulphur Oxides |

| CH4 | Methane |

| H2 | Hydrogen |

| H2S | Hydrogen Sulphide |

| Greenhouse Gases | GHG |

| Ionic Liquid | Ionic Liquid Name |

|---|---|

| [Ch][Lys] | Cholinium lysinate |

| [EMIM][BF4] | 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate |

| [EMIM][DCA] | 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium dicyanamide |

| (P666n PF6) | Trihexylalkylphosphonium hexafluorophosphate |

| [EMIM][NTf2] | 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium bis (trifluoromethylsulfonyl) imide |

| [BMIM][BF4] | 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate |

| AMMOENGTM 100 | Quaternary ammonium salts |

| EcoengTM 1111P | 1,3-Dimethylimidazolium dimethylphosphate |

| Cyphos 102 | Trihexyltetradecylphosphonium bromide |

| Cyphos 103 | Trihexyltetradecylphosphonium decanoate |

| Cyphos 104 | Trihexyltetradecylphosphonium bis(2,4,4-trimethylpentyl)phosphinate |

| [EMIM][CF3SO3] | 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium triflate |

| [SEt3][NTf2] | Triethylsulfonium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl) imide |

| [Cnmim][NTf2] (n = 2, 4, 6) | (1-Alkyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl) imide |

| [EMIM][OTf] | 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate |

| [MpFHim][NTf2] | 1-Methyl-3-(3,3,4,4,4-pentylfluorohexyl) imidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide |

| [MnFHim][NTf2] | 1-Methyl-3-(3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,6-nonafluorohexyl) imidazolium bis(trifluoromethyl - sulfonyl)imide |

| [MtdFHim][NTf2] | 1-Methyl-3-(3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,8-tridecylfluorohexyl)imidazolium bis(trifluoromethyl-sulfonyl)imide |

| [BMIM][NTf2] | 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium bis (trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide |

| OMIM TCM | 1-Methyl-3-octylimidazolium tricyanomethanide |

| [BMIM][Ac] | 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate |

| [EMIM][Ac] | 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate |

| [Vbtma][Ac] | Vinylbenzyl trimethylammonium acetate |

| [BMIM][TfO] | 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate |

| [BMIM][NTf2] | 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide |

| [BMIM][DCA] | 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium dicyanamide |

| [BMIM][BF4] | 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate |

| [BMIM][PhO] | 1-Butyl-3methylimidazolium phenolate |

| [pyr14][NTf2] | 1-Butyl-1-methylpyrrolidinium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide |

| [EMIM][TFSI] | 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide |

| [EMIM][EtSO4] | 1-Ethyl-3-methylimmidazolium-ethylsulphate |

| [BMIM][BETI] | 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(pentafluoroethylsulfonyl)imide |

| [BMIM][PF6] | 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate |

| [N(4)111][Tf2N] | Trimethyl(butyl)ammonium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide |

| [N(6)111][Tf2N] | Trimethyl(hexyl)ammonium bis(trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide |

| [N(10)111][Tf2N] | Trimethyl(decyl)ammonium bis(trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide |

| [N(6)222][Tf2N] | Triethyl(hexyl)ammonium bis(trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide |

| [N(1)444][Tf2N] | Tributyl(methyl)ammonium bis(trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide |

| [N(1)888][Tf2N] | Trioctyl(methyl)ammonium bis(trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide |

| [P(14)666][DCA] | Trihexyl(tetradecyl)phosphonium dicyanamide |

| [P(14)666][Tf2N] | Trihexyl(tetradecyl)phosphonium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide |

| [P(2)444][DEP] | Ethyl(tributyl)phosphonium diethylphosphate |

| [P(14)444][DBS] | Tributyl(ethyl)phosphonium diethylphosphate |

| [EMIM][C(CN)3] | 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium tricyanomethide |

| [EMIM][N(CN)2] | 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium dicyanamide |

| [P666n][PF6] | Trihexylalkylphosphonium hexafluorophosphate |

| Polymer Abbreviation | Polymer Name |

|---|---|

| PIM−1 | Polymers of intrinsic microporosity |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene fluoride |

| PES | Poly(ether-sulfone) polymer |

| PI | Polyimide |

| PVAc | Polyvinyl acetate |

| Ionic Liquid | Two Dimensional (2D) Structure | Three Dimensional (3D) Structure |

|---|---|---|

| [EMIM][DCA] |  |  |

| [EMIM][BF4] |  |  |

| [EMIM][Ac] |  |  |

| [EMIM][TFSI] |  |  |

| [BMIM][TFO] |  |  |

| [BMIM][BF4] |  |  |

| [BMIM][PF6] |  |  |

| Cyphos 104 |  |  |

| ′[HMIM][BF4] |  |  |

| Cation | Anion | Formula | m.w g/mol | m.t. °C | Visc cP 25 °C | Visc cP 50 °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIM | Cl | C4H7ClN2 | 118.6 | 74 | Solid | Solid |

| NO3 | C4H7N3O3 | 145.1 | 71 | Solid | Solid | |

| MMIM | Cl | C5H9ClN2 | 132.6 | 126 | Solid | Solid |

| EMIM | Cl | C6H11ClN2 | 146.6 | 89 | Solid | Solid |

| SCN | C7H11N3S | 169.3 | −6 | 29 | 12 | |

| Acetate NO3 | C8H14N2O2 C6H11N3O3 | 170.2 173.2 | −2 39 | 144 Solid | 39 | |

| N(CN)2Br | C8H11N5 C6H11BrN2 | 177.2 191.1 | −18 75 | 16 Solid | 9 Solid | |

| BF4 | C6H11BF4N2 | 198 | 13 | 35 | 18 | |

| Alaninate | C9H17N3O2 | 199.2 | 12 | 260 | 62 | |

| C(CN)3CH3SO3 | C10H11N5 C7H14N2O3S | 201.2 206.3 | −9 25 | 15 167 | 7 47 | |

| CF3SO3HSO4 | C7H11F3N2O3S C6H12N2O4S | 260.2 208.2 | −14 19 | 43 1600 | 20 360 | |

| CH3SO4 | C7H14N2O4S | 222.3 | −40 | 79 | 30 | |

| C2SO4 | C8H16N2O4S | 236.3 | −37 | 98 | 35 | |

| C4SO4 | C10H20N2O4S | 264.3 | −15 | 181 | 56 | |

| C6SO4C8SO4 | C12H24N2O4S C14H28N2O4S | 292.4 320.5 | −6 10 | 320 580 | 86,140 | |

| I | C6H11IN2 | 238.1 | 78 | Solid | Solid | |

| PF6 | C6H11F6N2P | 256.1 | 60 | Solid | Solid | |

| AlCl4 | C6H11AlCl4N2 | 280 | 6.5 | |||

| TolSO3 | C13H18N2O3S | 282.4 | 50 | Solid | 240 | |

| AsF6 | C6H11AsF6N2 | 300.1 | 53 | Solid | Solid | |

| NTf2 | C8H11F6N3O4S2 | 391.3 | −17 | 33 | 16 | |

| N(SO2C2F5)2 | C10H11F10N3O4S2 | 491.3 | −1 | |||

| EMMIM | Br | C7H13BrN2 | 205.1 | 141 | Solid | Solid |

| NTf2 | C9H13F6N3O4S2 | 405.3 | 25 | Solid | ||

| N(SO2C2F5)2 | C11H13F10N3O4S2 | 505.3 | 25 | Solid | ||

| PMIM | Cl | C7H13ClN2 | 160.6 | 62 | Solid | Solid |

| Br | C7H13BrN2 | 205.1 | 28 | Solid | ||

| BF4I | C7H13BF4N2 C7H13IN2 | 212 252.1 | −17 17 | 74 | 27 | |

| PF6 | C7H13F6N2P | 270.2 | 38 | Solid | ||

| NTf2 | C9H13F6N3O4S2 | 405.3 | 15 | 46 | 19 | |

| BMIM | Cl | C8H15ClN2 | 174.5 | 41 | Solid | 150 |

| SCN | C9H15N3S | 197.3 | −6 | 51 | 19 | |

| Acetate | C10H18N2O2 | 198.3 | −1 | 430 | 67 | |

| N(CN)2Br | C10H15N5 C8H15BrN2 | 205.3 219.1 | −5 75 | 42 Solid | 19 Solid | |

| BF4 | C8H15BF4N2 | 226 | −82 | 108 | 36 | |

| C(CN)3HSO4 | C12H15N5 C8H16N2O4S | 229.3 236.3 | −20 28 | 34 Solid | 12 | |

| ClO4 | C8H15ClN2O4 | 238.7 | 8 | 180 | 57 | |

| CH3SO4 | C9H18N2O4S C10H15F3N2O2 | 250.3 252.2 | −4 0 | 94 77 | 32 25 | |

| Trifluoroacetate | ||||||

| PF6 | C8H15F6N2P | 284.2 | 11 | 270 | 74 | |

| CF3SO3 | C9H15F3N2O3S | 288.3 | 14 | 80 | 31 | |

| Cyclohexyl sulfamate | C14H27N3O3S | 317.5 | 72.5 | Solid | Solid | |

| FeCl4 C8SO4 | C8H15Cl4FeN2 C16H32N2O4S | 337 348.5 | −12 24 | 41,870 | 18 152 | |

| NTf2 | C10H15F6N3O4S2 | 419.4 | −5 | 42 | 19 | |

| Isobutylmim MMMMmim | NTf2 NTf2 | C10H15F6N3O4S2 C10H15F6N3O4S2 | 419.4 419.4 | −16 118 | Solid | Solid |

| BMIM | Cl | C9H17ClN2 | 188.7 | 93 | Solid | Solid |

| BF4 | C9H17BF4N2 | 240.1 | 32 | Solid | 31 | |

| PF6 | C9H17F6N2P | 298.2 | 38 | Solid | ||

| NTf2 | C11H17F6N3O4S2 | 433.4 | −6 | 350 | 34 | |

| Allylmim Benzmim | N(CN)2Cl | C9H11N5 C11H13ClN2 | 189.2 208.7 | −20 14 | 20 3725 | 10 417 |

| CH3SO4 | C12H16N2O4S | 284.3 | 18 | 4500 | 327 | |

| PF6 | C11H13F6N2P | 318.2 | 130 | Solid | Solid | |

| C5mim | PF6 | C9H17F6N2P | 298.2 | 16 | 380 | 97 |

| NTf2 | C11H17F6N3O4S2 | 433.4 | −9 | 58 | 22 | |

| HMIM | N(CN)2 | C12H19N5 | 233.3 | 1 | 50 | 20 |

| BF4I | C10H19BF4N2 C10H19IN2 | 254.1 294.2 | −82 30 | 200 Solid | 58 246 | |

| PF6 CF3SO3 | C10H19F6N2P C11H19F3N2O3S | 312.2 316.3 | −61 25 | 480 Solid | 120 47 | |

| NTf2 | C12H19F6N3O4S2 | 447.4 | −6 | 70 | 27 |

| Room Temperature Ionic Liquid (RTIL) | Permeabilities (Barrers) CO2 | O2 | N2 | CH4 | Selectivities | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO2/N2 | CO2/CH4 | O2/N2 | |||||

| Imidazolium-RTILs [EMIM][BF4] | 968.5 | 32.1 | 21.8 | 43.7 | 44.5 | 22.2 | 1.5 |

| [EMIM][TfO] | 1171.4 | 60.8 | 28.9 | 63.2 | 40.5 | 18.5 | 2.1 |

| [EMIM][Tf2N] | 1702.4 | 143.5 | 73.6 | 139.2 | 23.1 | 12.2 | 1.9 |

| [C6mim][Tf2N] | 1135.8 | 121.6 | 73.9 | 134.0 | 15.4 | 8.5 | 1.6 |

| [BMIM][BETI] | 991.4 | 110.1 | 59.3 | 100.5 | 16.7 | 9.9 | 1.9 |

| [BMIM][PF6] | 544.3 | 36.2 | 21.2 | 40.8 | 25.6 | 13.3 | 1.7 |

| Ammonium-RTILs [N(4)111][Tf2N] | 830.5 | 97.6 | 40.5 | 63.1 | 20.5 | 13.2 | 2.4 |

| [N(6)111][Tf2N] | 943.2 | 97.0 | 46.2 | 102.1 | 20.4 | 9.2 | 2.1 |

| [N(10)111][Tf2N] | 800.4 | 106.0 | 53.9 | 105.0 | 14.8 | 7.6 | 2.0 |

| [N(6)11(i-3)][Tf2N] | 618.9 | 83.2 | 44.4 | 73.8 | 13.9 | 8.4 | 1.9 |

| [N(10)11(i-3)][Tf2N] | 632.8 | 96.0 | 67.5 | 114.3 | 9.4 | 5.5 | 1.4 |

| [N(6)222][Tf2N] | 630.3 | 67.9 | 31.9 | 64.5 | 19.8 | 9.8 | 2.1 |

| [N(1)444][Tf2N] | 523.9 | 74.4 | 35.3 | 68.5 | 14.8 | 7.6 | 2.1 |

| [N(1)888][Tf2N] | 619.4 | 116.0 | 54.9 | 138.9 | 11.3 | 4.5 | 2.1 |

| Phosphonium-RTILs [P(14)666][Cl]-Source B | 377.6 | 68.3 | 35.9 | 112.9 | 10.5 | 3.3 | |

| [P(14)666][DCA] | 513.7 | 87.1 | 36.2 | 107.6 | 14.2 | 4.8 | |

| [P(14)666][Tf2N] | 689.1 | 137.1 | 64.1 | 169.8 | 10.7 | 4.1 | |

| [P(2)444][DEP] | 453.4 | 71.5 | 31.0 | 90.1 | 14.6 | 5.0 | |

| [P(14)444][DBS] | 231.7 | 34.4 | 14.3 | 68.7 | 16.2 | 3.4 | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elhenawy, S.; Khraisheh, M.; AlMomani, F.; Hassan, M. Key Applications and Potential Limitations of Ionic Liquid Membranes in the Gas Separation Process of CO2, CH4, N2, H2 or Mixtures of These Gases from Various Gas Streams. Molecules 2020, 25, 4274. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/molecules25184274

Elhenawy S, Khraisheh M, AlMomani F, Hassan M. Key Applications and Potential Limitations of Ionic Liquid Membranes in the Gas Separation Process of CO2, CH4, N2, H2 or Mixtures of These Gases from Various Gas Streams. Molecules. 2020; 25(18):4274. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/molecules25184274

Chicago/Turabian StyleElhenawy, Salma, Majeda Khraisheh, Fares AlMomani, and Mohamed Hassan. 2020. "Key Applications and Potential Limitations of Ionic Liquid Membranes in the Gas Separation Process of CO2, CH4, N2, H2 or Mixtures of These Gases from Various Gas Streams" Molecules 25, no. 18: 4274. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/molecules25184274