Anti-Neuroinflammatory Property of Phlorotannins from Ecklonia cava on Aβ25-35-Induced Damage in PC12 Cells

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

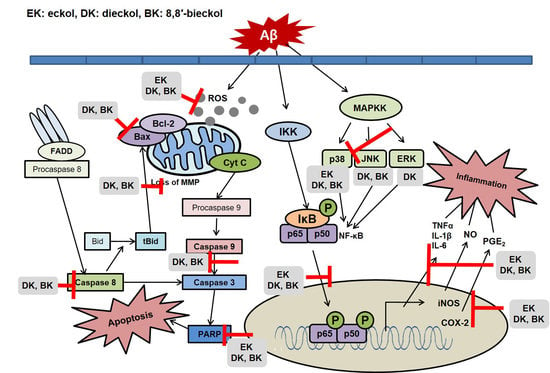

2.1. Major Phlorotannins Derived from E. cava Protected PC12 Cells Against Aβ25-35-Induced Cytotoxicity and Apoptosis

2.2. Major Phlorotannins Derived from E. cava Inhibited Aβ25-35-Induced Expression of Apoptotic Pathway Proteins

2.3. Major Phlorotannins Derived from E. cava Reduced Aβ25-35-Induced Expression of Inflammatory Mediators

2.4. Major Phlorotannins Derived from E. cava Attenuated Aβ25-35-Induced NF-κB and MAPK Activation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Reagents

3.2. Preparation of Aβ Aggregation

3.3. Cell Culture and Treatments

3.4. Measurement of Cell Viability

3.5. Flow Cytometry Analysis

3.6. Determination of ROS and Cellular Apoptosis

3.7. Evaluation of NO and PGE2 Levels

3.8. Measurement of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (MMP) and Intracellular Free Calcium

3.9. Western Blot Analysis

3.10. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gouras, G.; Olsson, T.; Hansson, O. β-Amyloid peptides and amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurotherapeutics 2015, 12, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Q.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J. Inhibition of protein phosphatases induces transport deficits and axonopathy. J. Neurochem. 2007, 102, 878–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ren, Q.; Liao, X.; Chen, X.; Liu, G.; Wang, J. Effects of tau phosphorylation on proteasome activity. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 1521–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Iqbal, K.; Alonso Adel, C.; Chen, S.; Chohan, M.; El-Akkad, E.; Gong, C.; Khatoon, S.; Li, B.; Liu, F.; Rahman, A.; et al. Tau pathology in Alzheimer disease and other tauopathies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2005, 1739, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, F.; Zhou, X.; Yang, Q.; Xu, W.; Wang, F.; Chen, Y.; Chen, G. A peptide that binds specifically to the β-amyloid of Alzheimer’s disease: Selection and assessment of anti-β-amyloid neurotoxic effects. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e27649–e27658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmore, S. Apoptosis: A review of programmed cell death. Toxicol. Pathol. 2007, 35, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supnet, C.; Bezprozvanny, I. Neuronal calcium signaling, mitochondrial dysfunction, and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2010, 20, S487–S498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Ghosh, S. NF-kappaB, an evolutionarily conserved mediator of immune and inflammatory responses. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2005, 560, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wijesekara, I.; Yoon, N.; Kim, S. Phlorotannins from Ecklonia cava (Phaeophyceae): Biological activities and potential health benefits. Biofactors 2010, 36, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Chung, H.; Kim, J.; Son, B.; Jung, H.; Choi, J. Inhibitory phlorotannins from the edible brown alga Ecklonia stolonifera on total reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2004, 27, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.; Ahn, Y.; Lee, S.; Choi, Y.; Kim, S.; Yea, S.; Choi, I.; Park, S.; Seo, S.; Lee, S.; et al. Ecklonia cava ethanolic extracts inhibit lipopolysaccharide-induced cyclooxygenase-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in BV2 microglia via the MAP kinase and NF-kappaB pathways. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009, 47, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, G.; Hwang, I.; Park, E.; Kim, J.; Jeon, Y.; Lee, J.; Park, J.; Jee, Y. Immunomodulatory effects of an enzymatic extract from Ecklonia cava on murine splenocytes. Mar. Biotechnol. 2008, 10, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Lee, D.; Jung, W.; Kim, J.; Choi, I.; Park, S.; Seo, S.; Lee, S.; Lee, C.; Yea, S.; et al. Effects of Ecklonia cava ethanolic extracts on airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation in a murine asthma model: Role of suppressor of cytokine signaling. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2008, 62, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, I.; Jeon, Y.; Yin, X.; Nam, J.; You, S.; Hong, M.; Jang, B.; Kim, M. Butanol extract of Ecklonia cava prevents production and aggregation of beta-amyloid, and reduces beta-amyloid mediated neuronal death. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011, 49, 2252–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, I.; Jang, B.; In, S.; Choi, B.; Kim, M.; Kim, M. Phlorotannin-rich Ecklonia cava reduces the production of beta-amyloid by modulating alpha- and gamma-secretase expression and activity. Neurotoxicology 2013, 34, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, S.; Cha, S.; Kim, K.; Lee, S.; Ahn, G.; Kang, D.; Oh, C.; Choi, Y.; Affan, A.; Kim, D.; et al. Neuroprotective effect of phlorotannin isolated from Ishige okamurae against H2O2-induced oxidative stress in murine hippocampal neuronal cells, HT22. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012, 166, 1520–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, N.; Jeong, Y.; Lee, J.; Kim, E.; Han, S. Protective efficacy of an Ecklonia cava extract used to treat transient focal ischemia of the rat brain. Anat. Cell Biol. 2012, 45, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.; Cha, S.; Ko, J.; Kang, M.; Kim, D.; Heo, S.; Kim, J.; Heu, M.; Kim, Y.; Jung, W.; et al. Neuroprotective effects of phlorotannins isolated from a brown alga, Ecklonia cava, against H2O2-induced oxidative stress in murine hippocampal HT22 cells. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2012, 34, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, J.; Yoo, S.; Kwon, S. Cytoprotective effect of dieckol on human endothelial progenitor cells (hEPCs) from oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. Free Radic. Res. 2013, 47, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J.H.; Castañeda, H.G. Preparation and chromatographic analysis of phlorotannins. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2013, 51, 825–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, T.; Kanji, I.; Kawaguchi, S.; Yoshikawa, H.; Hama, Y. Antioxidant activities of phlorotannins isolated from Japanese Laminariaceae. J. Appl. Phycol. 2008, 20, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathya, R.; Kanaga, N.; Sankar, P.; Jeeva, S. Antioxidant properties of phlorotannins from brown seaweed Cystoseira trinodis (Forsskål) C. Agardh. Arab. J. Chem. 2017, 10, 2608S–2614S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Jeon, H.; Lee, O.; Lee, B. Dieckol, a major phlorotannin in Ecklonia cava, suppresses lipid accumulation in the adipocytes of high-fat diet-fed zebrafish and mice: Inhibition of early adipogenesis via cell-cycle arrest and AMPKα activation. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2015, 59, 1458–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, J.; Yang, Y.; Lee, K.; Choi, J. Dieckol, isolated from the edible brown algae Ecklonia cava, induces apoptosis of ovarian cancer cells and inhibits tumor xenograft growth. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 141, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naseer, M.; Lee, H.; Ullah, N.; Ullah, I.; Park, M.; Kim, S.; Kim, M. Ethanol and PTZ effects on siRNA-mediated GABAB1 receptor: Down regulation of intracellular signaling pathway in prenatal rat cortical and hippocampal neurons. Synapse 2010, 64, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, D.; Korsmeye, S. Bcl-2 family: Regulators of cell death. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1998, 16, 395–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, S. Apoptosis and brain ischemia. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiartry 2003, 27, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Woo, J.; Seo, Y.; Lee, K.; Lim, Y.; Choi, J. Protective Effect of Brown Alga Phlorotannins against Hyper-inflammatory Responses in Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Sepsis Models. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Jung, S.; Lee, K.; Choi, J. 8,8′-Bieckol, isolated from edible brown algae, exerts its anti-inflammatory effects through inhibition of NF-κB signaling and ROS production in LPS-stimulated macrophages. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2014, 23, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, Y.; Usui, M.; Katsuzaki, H.; Imai, K.; Kakinuma, M.; Amano, H.; Miyata, M. Orally Administered Phlorotannins from Eisenia arborea Suppress Chemical Mediator Release and Cyclooxygenase-2 Signaling to Alleviate Mouse Ear Swelling. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-Y.; Kim, E.-A.; Kang, M.-C.; Lee, J.-H.; Yang, H.-W.; Lee, J.-S.; Lim, T.; Jeon, Y.-J. Polyphenol-rich fraction from Ecklonia cava (a brown alga) processing by-product reduces LPS-induced inflammation in vitro and in vivo in a zebrafish model. Algae 2014, 29, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Yadav, A.; Chaturvedi, R. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) as therapeutic target in neurodegenerative disorders. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 483, 1166–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Park, J.; Wu, J.; Lee, J.; Yang, Y.; Kang, M.; Jung, S.; Park, J.; Yoo, E.; Kim, S.; et al. Dieckol Attenuates Microglia-mediated Neuronal Cell Death via ERK, Akt and NADPH Oxidase-mediated Pathways. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2015, 19, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, N.; Koo, D.; Kang, G.; Han, S.; Lee, B.; Koh, Y.; Hyun, J.; Lee, N.; Ko, M.; Kang, H.; et al. Dieckol, a Component of Ecklonia cava, Suppresses the Production of MDC/CCL22 via Down-Regulating STAT1 Pathway in Interferon-γ Stimulated HaCaT Human Keratinocytes. Biomol. Ther. (Seoul) 2015, 23, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Zhou, J.; Tang, X. Tacrine attenuates hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis by regulating expression of apoptosis-related genes in rat PC12 cells. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2002, 107, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; Youn, K.; Ho, C.; Karwe, M.; Jeong, W.; Jun, M. p-Coumaric acid and ursolic acid from Corni fructus attenuated β-amyloid(25-35)-induced toxicity through regulation of the NF-κB signaling pathway in PC12 cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 4911–4916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dholakiya, S.; Benzeroual, K. Protective effect of diosmin on LPS-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells and inhibition of TNF-α expression. Toxicol. In Vitro 2011, 25, 1039–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pera, M.; Camps, P.; Muñoz-Torrero, D.; Perez, B.; Badia, A.; Clos Guillen, M. Undifferentiated and differentiated PC12 cells protected by huprines against injury induced by hydrogen peroxide. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Li, W.; Dong, M. Flavonoids of Kudzu Root Fermented by Eurtotium cristatum Protected Rat Pheochromocytoma Line 12 (PC12) Cells against H2O2-Induced Apoptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shal, B.; Ding, W.; Ali, H.; Kim, Y.; Khan, S. Anti-neuroinflammatory Potential of Natural Products in Attenuation of Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 29, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B. Natural antioxidants for neurodegenerative diseases. Mol. Neurobiol. 2005, 31, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, T.; Pawlus, A.; Iglésias, M.-L.; Pedrot, E.; Waffo-Teguo, P.; Mérillon, J.-M.; Monti, J.-P. Neuroprotective properties of resveratrol and derivatives. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1215, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhagat, J.; Kaur, A.; Kaur, R.; Yadav, A.; Sharma, V.; Chadha, B. Cholinesterase inhibitor (Altenuene) from an endophytic fungus Alternaria alternata: Optimization, purification and characterization. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 121, 1015–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.; Seong, S.; Reddy, M.; Seo, S.; Choi, J.; Jung, H. Kinetics and Molecular Docking Studies of 6-Formyl Umbelliferone Isolated from Angelica decursiva as an Inhibitor of Cholinesterase and BACE1. Molecules 2017, 22, 1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pate, K.M.; Rogers, M.; Reed, J.W.; van der Munnik, N.; Vance, S.Z.; Mossa, M.A. Anthoxanthin polyphenols attenuate oligomer-induced neuronal responses associated with Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2017, 23, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piemontese, L.; Vitucci, G.; Catto, M.; Laghezza, A.; Perna, F.M.; Rullo, M.G.; Loiodice, F.; Capriati, V.; Solfrizzo, M. Natural Scaffolds with Multi-Target Activity for the Potential Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Molecules 2018, 23, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, T.; Kawaguchi, S.; Hama, Y.; Inagaki, M.; Yamaguchi, K.; Nakamura, T. Local and chemical distribution of phlorotannins in brown algae. J. Appl. Phycol. 2004, 16, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.; Bangoura, I.; Kang, J.; Park, N.; Ahn, D.; Hong, Y. Distribution of Phlorotannins in the Brown Alga Ecklonia cava and Comparison of Pretreatments for Extraction. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2011, 143, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rege, S.; Geetha, T.; Griffin, G.; Broderick, T.; Babu, J. Neuroprotective effects of resveratrol in Alzheimer disease pathology. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014, 6, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Taghibiglou, C. The Mechanisms of Action of Curcumin in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2017, 58, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascella, M.; Bimonte, S.; Muzio, M.; Schiavone, V.; Cuomo, A. The efficacy of Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (green tea) in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: An overview of pre-clinical studies and translational perspectives in clinical practice. Infect. Agent. Cancer 2017, 12, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.; Oh, S.; Choi, J. Molecular docking studies of phlorotannins from Eisenia bicyclis with BACE1 inhibitory activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 3211–3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myung, C.; Shin, H.; Bao, H.; Yeo, S.; Lee, B.; Kang, J. Improvement of memory by dieckol and phlorofucofuroeckol in ethanol-treated mice: Possible involvement of the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2005, 28, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagayama, K.; Iwamura, Y.; Shibata, T.; Hirayama, I.; Nakamura, T. Bactericidal activity of phlorotannins from the brown alga Ecklonia kurome. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2002, 50, 889–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rengasamy, K.; Kulkarni, M.; Stirk, W.; Staden, J. Advances in algal drug research with emphasis on enzyme inhibitors. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014, 32, 1364–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, J.; Yang, Z.; Yoon, B.; He, Y.; Uhm, S.; Shin, H.; Lee, B.; Yoo, Y.; Lee, K.; Han, S.; et al. Blood-brain barrier-permeable fluorone-labeled dieckols acting as neuronal ER stress signaling inhibitors. Biomaterials 2015, 61, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S.; Youn, K.; Kim, D.H.; Ahn, M.-R.; Yoon, E.; Kim, O.-Y.; Jun, M. Anti-Neuroinflammatory Property of Phlorotannins from Ecklonia cava on Aβ25-35-Induced Damage in PC12 Cells. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 7. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/md17010007

Lee S, Youn K, Kim DH, Ahn M-R, Yoon E, Kim O-Y, Jun M. Anti-Neuroinflammatory Property of Phlorotannins from Ecklonia cava on Aβ25-35-Induced Damage in PC12 Cells. Marine Drugs. 2019; 17(1):7. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/md17010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Seungeun, Kumju Youn, Dong Hyun Kim, Mok-Ryeon Ahn, Eunju Yoon, Oh-Yoen Kim, and Mira Jun. 2019. "Anti-Neuroinflammatory Property of Phlorotannins from Ecklonia cava on Aβ25-35-Induced Damage in PC12 Cells" Marine Drugs 17, no. 1: 7. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/md17010007