Using Social Norms to Change Behavior and Increase Sustainability in the Real World: a Systematic Review of the Literature

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Social Norms and Behavioral Change

1.1.1. The Importance of the Attributes of Social Norms and Behaviors

1.1.2. The Importance of the Context

1.2. Our Review

- (1)

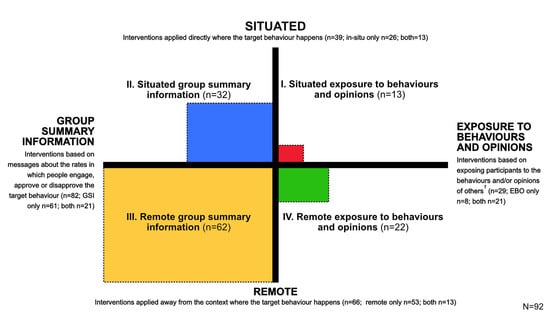

- Context of application (situated vs remote). The contexts in which intervention mechanisms are applied relative to the target behavior (specifically, following Lahlou [27], whether they are applied in the context where the target behavior happens or away from it)

- (2)

- Type of normative information (group summary information vs exposure to behaviors and opinions). The type of normative information that are intentionally leveraged in the intervention to influence behavior (specifically, following Tankard & Paluck [3], whether interventions rely on group summary information or exposure to the behaviors of others)

- (3)

- Intervention mechanisms. The different intervention mechanisms that are used to leverage the physical, psychological and social determinants of behavior (following Lahlou [27])

- (4)

- Combination of mechanisms. How the previous three elements are combined in the studies in the literature

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation and literature search

2.2. Eligibility Criteria and Additional Searches

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Situated and Remote Interventions

3.2. Interventions Based on Group Summary Information and on Exposure to Behaviors and Opinions

3.3. How are These Dimensions Combined in Interventions?

- (1)

- The main axis, which accounts for most of the variance in the sample, opposes “lighter” interventions applied remotely, using GSI and digital platforms mainly on students (which as we have seen constitutes the bulk of our sample and is associated with quadrant III), with more complex interventions done in-situ, using exposure to behaviors and opinions, and relying on a wider variety of interventions mechanisms (associated with quadrant I). Characteristics associated with each of these groups are presented in Table 3.

- (2)

- When including only studies that recorded behavior (excluding self-reported measures) finding relevant effects on behavior appears more frequently among interventions in the group 2 (quadrant I). On the other hand, not finding effects is more frequent among interventions in the group 1 (quadrant III). Nevertheless, these results should be taken with caution, as they are based on a limited subsample of 28 studies (in which 25 found effects and three didn’t), and there is a great diversity of experimental contexts, targets and treatments in them.

4. Discussion and Recommendations for Policy Application

How to Design more Integral and Sustainable Interventions based on Social Norms: “Get Closer”

5. Limitations and Further Research

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | Reference | Author(s) | Year | Title | Country | Intervention Topic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [94] | Agha and Van Rossem | 2004 | Impact of a school-based peer sexual health intervention on normative beliefs, risk perceptions, and sexual behavior of Zambian adolescents. | Zambia | Sexual health/HIV |

| 2 | [95] | Balvig and Holmberg | 2011 | The ripple effect: A randomized trial of a social norms intervention in a Danish middle school setting. | Denmark | Health behavior |

| 3 | [33] | Bateson et al. | 2013 | Do images of “watching eyes” induce behaviour that is more pro-social or more normative? A field experiment on littering. | UK | Pro-environmental |

| 4 | [137] | Bauer et al. | 2017 | Financial Incentives Beat Social Norms: A Field Experiment on Retirement Information Search. | Netherlands | Tax and retirement |

| 5 | [139] | Bertholet et al. | 2016 | Are young men who overestimate drinking by others more likely to respond to an electronic normative feedback brief intervention for unhealthy alcohol use? | Switzerland | Alcohol |

| 6 | [37] | Bewick et al. | 2013 | The effectiveness of a Web-based personalized feedback and social norms alcohol intervention on United Kingdom university students: Randomized controlled trial. | UK | Alcohol |

| 7 | [109] | Bewick et al. | 2008 | The feasibility and effectiveness of a web-based personalised feedback and social norms alcohol intervention in UK university students: A randomised control trial. | UK | Alcohol |

| 8 | [140] | Boen et al. | Unpublished | Portraying role models to promote stair climbing in a public setting: The effect of matching sex and age | Germany | Health behavior |

| 9 | [88] | Boyle et al. | 2017 | PNF 2.0? Initial evidence that gamification can increase the efficacy of brief, web-based personalized normative feedback alcohol interventions. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 10 | [135] | Brent et al. | 2017 | Are Normative Appeals Moral Taxes? Evidence from A Field Experiment on Water Conservation | U.S. | Pro-environmental |

| 11 | [136] | Bruce and Keller | 2007 | Applying Social Norms Theory within groups: Promising for high-risk drinking. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 12 | [80] | Brudermann et al. | 2017 | Eyes on social norms: A field study on an honor system for newspaper sale. | Austria | Integrity - morality |

| 13 | [40] | Celio and Lisman | 2014 | Examining the efficacy of a personalized normative feedback intervention to reduce college student gambling. | U.S. | Gambling |

| 14 | [38] | Chernoff and Davison | 2005 | An evaluation of a brief HIV/AIDS prevention intervention for college students using normative feedback and goal setting. | U.S. | Sexual health / HIV |

| 15 | [141] | Cleveland et al. | 2013 | Moderation of a parent-based intervention on transitions in drinking: Examining the role of normative perceptions and attitudes among high- and low-risk first-year college students. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 16 | [142] | Collins et al. | 2002 | Mailed personalized normative feedback as a brief intervention for at-risk college drinkers. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 17 | [143] | Collins et al. | 2014 | Randomized controlled trial of web-based decisional balance feedback and personalized normative feedback for college drinkers. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 18 | [87] | Cross and Peisner | 2009 | RECOGNIZE: A social norms campaign to reduce rumor spreading in a junior high school. | U.S. | Bullying / harassment behavior |

| 19 | [144] | Cunningham and Wong | 2013 | Assessing the immediate impact of normative drinking information using an immediate post-test randomized controlled design: Implications for normative feedback interventions? | Canada | Alcohol |

| 20 | [96] | Davis et al. | 2016 | Brief Motivational Interviewing and Normative Feedback for Adolescents: Change Language and Alcohol Use Outcomes. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 21 | [145] | Dejong et al. | 2006 | A multisite randomized trial of social norms marketing campaigns to reduce college student drinking: A replication failure. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 22 | [146] | Doumas and Hannah | 2008 | Preventing high-risk drinking in youth in the workplace: A web-based normative feedback program. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 23 | [147] | Doumas et al. | 2010 | Reducing heavy drinking among first year intercollegiate athletes: A randomized controlled trial of web-based normative feedback. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 24 | [148] | Doumas et al. | 2011 | Reducing high-risk drinking in mandated college students: Evaluation of two personalized normative feedback interventions. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 25 | [17] | Flüchter et al. | 2014 | Digital commuting: The effect of social normative feedback on e-bike commuting - Evidence from a field study. | Switzerland | Pro-environmental |

| 26 | [36] | Gidycz et al. | 2011 | Preventing sexual aggression among college men: An evaluation of a social norms and bystander intervention program. | U.S. | Bullying / harassment behavior |

| 27 | [64] | Hallsworth et al. | 2016 | Provision of social norm feedback to high prescribers of antibiotics in general practice: a pragmatic national randomised controlled trial. | UK | Health behavior |

| 28 | [149] | Hartwell and Campion | 2016 | Getting on the same page: The effect of normative feedback interventions on structured interview ratings. | U.S. | Rating of interviews |

| 29 | [19] | Hopper et al. | 1991 | Recycling as altruistic behavior: Normative and Behavioral Strategies to Expand Participation in a Community Recycling Program. | U.S. | Pro-environmental |

| 30 | [150] | Howe et al. | Unpublished | Normative Appeals Are More Effective When They Invite People to Work Together Toward a Common Cause | U.S. | Pro-environmental |

| 31 | [93] | Kearney et al. | 2013 | The impact of an alcohol education program using social norming. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 32 | [151] | Koeneman et al. | 2017 | A novel method to promote physical activity among older adults in residential care: An exploratory field study on implicit social norms. | Netherlands | Health behavior |

| 33 | [16] | Kormos et al. | 2015 | The Influence of Descriptive Social Norm Information on Sustainable Transportation Behavior: A Field Experiment. | Canada | Pro-environmental |

| 34 | [152] | Kulik et al. | 2008 | Social norms information enhances the efficacy of an appearance-based sun protection intervention. | U.S. | Health behavior |

| 35 | [153] | Labrie et al. | 2009 | A brief live interactive normative group intervention using wireless keypads to reduce drinking and alcohol consequences in college student athletes. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 36 | [85] | Lahlou et al. | 2015 | Increasing water intake of children and parents in the family setting: a randomized, controlled intervention using installation theory. | Poland | Water intake |

| 37 | [24] | Lapinski et al. | 2013 | Testing the Effects of Social Norms and Behavioral Privacy on Hand Washing: A Field Experiment. | U.S. | Health behavior |

| 38 | [90] | Latkin et al. | 2013 | The dynamic relationship between social norms and behaviors: the results of an HIV prevention network intervention for injection drug users. | U.S. | Sexual health / HIV |

| 39 | [154] | Lewis, and Neighbors | 2006 | An Examination of College Student Activities and Attentiveness During a Web-Delivered Personalized Normative Feedback Intervention. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 40 | [119] | Lewis et al. | 2008 | 21st Birthday Celebratory Drinking: Evaluation of a Personalized Normative Feedback Card Intervention. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 41 | [132] | Lewis et al. | 2014 | Randomized controlled trial of a web-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention to reduce alcohol-related risky sexual behavior among college students. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 42 | [155] | Lojewski et al. | 2010 | Personalized normative feedback to reduce drinking among college students: A social norms intervention examining gender-based versus standard feedback. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 43 | [156] | Mattern and Neighbors | 2004 | Social norms campaigns: Examining the relationship between changes in perceived norms and changes in drinking levels. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 44 | [39] | McCoy et al. | 2017 | Pilot study of a multi-pronged intervention using social norms and priming to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy and retention in care among adults living with HIV in Tanzania. | Tanzania | Sexual health / HIV |

| 45 | [6] | Mockus | 2002 | Co-existence as harmonization of law, morality and culture. | Colombia | Pro-environmental—Use of pedestrian crossings |

| 46 | [92] | Mogro-Wilson et al. | 2017 | A Brief High School Prevention Program to Decrease Alcohol Usage and Change Social Norms. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 47 | [20] | Mollen et al. | 2013 | Healthy and unhealthy social norms and food selection. Findings from a field-experiment. | U.S. | Health behavior |

| 48 | [157] | Mollen et al. | 2013 | Intervening or interfering? The influence of injunctive and descriptive norms on intervention behaviours in alcohol consumption contexts. | Netherlands | Alcohol |

| 49 | [84] | Moore et al. | 2013 | An exploratory cluster randomised trial of a university halls of residence based social norms marketing campaign to reduce alcohol consumption among 1st year students. | UK | Alcohol |

| 50 | [158] | Moreira et al. | 2012 | Personalised Normative Feedback for Preventing Alcohol Misuse in University Students: Solomon Three-Group Randomised Controlled Trial. | UK | Alcohol |

| 51 | [89] | Neighbors et al. | 2004 | Targeting misperceptions of descriptive drinking norms: Efficacy of a computer-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 52 | [159] | Neighbors et al. | 2010 | Efficacy of web-based personalized normative feedback: A two-year randomized controlled trial. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 53 | [160] | Neighbors et al. | 2011 | Social-norms interventions for light and nondrinking students. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 54 | [41] | Neighbors et al. | 2015 | Efficacy of personalized normative feedback as a brief intervention for college student gambling: A randomized controlled trial. | U.S. | Gambling |

| 55 | [161] | Neighbors et al. | 2006 | Being controlled by normative influences: Self-determination as a moderator of a normative feedback alcohol intervention. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 56 | [35] | Paluck and Shepherd H. | 2012 | The salience of social referents: A field experiment on collective norms and harassment behavior in a school social network. | U.S. | Bullying / harassment behavior |

| 57 | [22] | Payne et al. | 2015 | Shopper marketing nutrition interventions: Social norms on grocery carts increase produce spending without increasing shopper budgets. | U.S. | Health behavior |

| 58 | [162] | Pedersen et al. | 2016 | A randomized controlled trial of a web-based, personalized normative feedback alcohol intervention for young-adult veterans. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 59 | [14] | Pellerano et al. | 2016 | Do Extrinsic Incentives Undermine Social Norms? Evidence from a Field Experiment in Energy Conservation. | Ecuador | Pro-environmental |

| 60 | [129] | Perkins and Craig | 2006 | A successful social norms campaign to reduce alcohol misuse among college student-athletes. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 61 | [163] | Perkins et al. | 2011 | Using social norms to reduce bullying: A research intervention among adolescents in five middle schools. | U.S. | Bullying / harassment behavior |

| 62 | [111] | Perkins et al. | 2010 | Effectiveness of social norms media marketing in reducing drinking and driving: A statewide campaign. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 63 | [25] | Pfattheicher et al. | Unpublished | A Field Study on Watching Eyes and Hand Hygiene Compliance in a Public Restroom | Germany | Health behavior |

| 64 | [98] | Prince et al. | 2015 | Development of a Face-to-Face Injunctive Norms Brief Motivational Intervention for College Drinkers and Preliminary Outcomes. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 65 | [164] | Reid and Aiken | 2013 | Correcting injunctive norm misperceptions motivates behavior change: A randomized controlled sun protection intervention. | U.S. | Health behavior |

| 66 | [165] | Reilly and Wood | 2008 | A randomized test of a small-group interactive social norms intervention. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 67 | [166] | Ridout and Campbell | 2014 | Using facebook to deliver a social norm intervention to reduce problem drinking at university. | Australia | Alcohol |

| 68 | [167] | Schultz and Tyra | Unpublished | Two Field Studies of Normative Beliefs and Environmental Behavior | U.S. | Pro-envirnomental |

| 69 | [15] | Schultz et al. | 2016 | Personalized normative feedback and the moderating role of personal norms: A field experiment to reduce residential water consumption. | U.S. | Pro-environmental |

| 70 | [168] | Schultz et al. | Unpublished | Normative Social Influence Transcends Culture, But Detecting It Is Culture Specific | Multiple | Alcohol |

| 71 | [18] | Schultz | 1999 | Changing behavior with normative feedback interventions: A field experiment on curbside recycling. | U.S. | Pro-envirnomental |

| 72 | [169] | Scribner et al. | 2011 | Alcohol prevention on college campuses: The moderating effect of the alcohol environment on the effectiveness of social norms marketing campaigns. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 73 | [130] | Silk et al. | 2017 | Evaluation of a Social Norms Approach to a Suicide Prevention Campaign. | U.S. | Counselling service use |

| 74 | [131] | Smith et al. | 2006 | A social judgment theory approach to conducting formative research in a social norms campaign. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 75 | [124] | Spijkerman et al. | 2010 | Effectiveness of a Web-based brief alcohol intervention and added value of normative feedback in reducing underage drinking: A randomized controlled trial. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 76 | [170] | Stamper et al. | 2004 | Replicated findings of an evaluation of a brief intervention designed to prevent high-risk drinking among first-year college students: Implications for social norming theory. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 77 | [171] | Steffian | 1999 | Correction of normative misperceptions: An alcohol abuse prevention program. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 78 | [172] | Su et al. | 2017 | Evaluating the Effect of a Campus-wide Social Norms Marketing Intervention on Alcohol Use Perceptions, Consumption, and Blackouts. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 79 | [173] | Taylor et al. | 2015 | Improving social norms interventions: Rank-framing increases excessive alcohol drinkers’ information-seeking. | UK | Alcohol |

| 80 | [174] | Thombs et al. | 2007 | Outcomes of a technology-based social norms intervention to deter alcohol use in freshman residence halls. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 81 | [127] | Thombs et al. | 2004 | A close look at why one social norms campaign did not reduce student drinking. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 82 | [21] | Thorndike et al. | 2016 | Social norms and financial incentives to promote employees’ healthy food choices: A randomized controlled trial. | U.S. | Health behavior |

| 83 | [134] | Toghianifar et al. | 2014 | Women’s attitude toward smoking: effect of a community-based intervention on smoking-related social norms. | Iran | Health behavior |

| 84 | [133] | Turner et al. | 2008 | Declining negative consequences related to alcohol misuse among students exposed to a social norms marketing intervention on a college campus. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 85 | [81] | Wall and Cameron | 2017 | Trial of Social Norm Interventions to Increase Physical Activity. | U.S. | Health behavior |

| 86 | [175] | Wegs et al. | 2016 | Community Dialogue to Shift Social Norms and Enable Family Planning: An Evaluation of the Family Planning Results Initiative in Kenya. | Kenya | Sexual health/HIV |

| 87 | [176] | Wenzel | 2005 | Misperceptions of social norms about tax compliance: From theory to intervention. | Australia | Tax and retirement |

| 88 | [120] | Werch et al. | 2000 | Results of a social norm intervention to prevent binge drinking among first-year residential college students. | U.S. | Alcohol |

| 89 | [91] | Yurasek et al. | 2015 | Descriptive Norms and Expectancies as Mediators of a Brief Motivational Intervention for Mandated College Students Receiving Stepped Care for Alcohol Use. | U.S. | Alcohol |

References

- Darnton, A. Reference Report: An Overview of Behaviour Change Models and Their Uses. In GSR Behaviour Change Knowledge Review; Government Social Research: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bicchieri, C. Norms in the Wild: How to Diagnose, Measure and Change Social Norms; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tankard, M.; Paluck, E.L. Norm Perception as a Vehicle for Social Change. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2016, 10, 181–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie-Mohr, D. Fostering Sustainable Behavior: An Introduction to Community-Based Social Marketing; New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, BC, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mackie, G. Effective Rule of Law Requires Construction of A Social Norm of Legal Obedience. In Cultural Agents Reloaded: The Legacy of Antanas Mockus; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mockus, A. Co-Existence as Harmonization of Law, Morality and Culture. Prospects2 2002, XXXII, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamin, P. Politics (and Mime Artists) on the Street. In Return to the Street; Henri, T., Fuggle, S., Eds.; Pavement Books: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Darnton, A. Practical Guide: An Overview of Behaviour Change Models and Their Uses. In GSR Behaviour Change Knowledge Review; Government Social Research: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D.T.; Prentice, D.A. The Construction of Social Norms and Standards. In Social psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles; Higgins, F.T., Kruglanski, A.W., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 799–829. [Google Scholar]

- Bicchieri, C.; Lindemans, J.W.; Jiang, T. A Structured Approach to a Diagnostic of Collective Practices. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, P.; Sanders, M.; Wang, J. The Use of Descriptive Norms in Public Administration: A Panacea for Improving Citizen Behaviours; SSRN Papers; SSRN: Rochester, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sunstein, C.R. The Council of Psychological Advisers. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2016, 67, 713–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Legros, S.; Cislaghi, B. Mapping the Social Norms Literature: An Overview of Reviews Sophie. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2019, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Pellerano, J.A.; Price, M.K.; Puller, S.L.; Sánchez, G.E. Do Extrinsic Incentives Undermine Social Norms? Evidence from a Field Experiment in Energy Conservation. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2016, 67, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Messina, A.; Tronu, G.; Limas, E.F.; Gupta, R.; Estrada, M. Personalized Normative Feedback and the Moderating Role of Personal Norms: A Field Experiment to Reduce Residential Water Consumption. Environ. Behav. 2016, 48, 686–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kormos, C.; Gifford, R.; Brown, E. The Influence of Descriptive Social Norm Information on Sustainable Transportation Behavior: A Field Experiment. Environ. Behav. 2015, 47, 479–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flüchter, K.; Wortmann, F.; Fleisch, E. Digital Commuting: The Effect of Social Normative Feedback on e-Bike Commuting—Evidence from a Field Study. In ECIS 2014 Proceedings—22nd European Conference on Information Systems; ETH Zurich: Zurich, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, P.W. Changing Behavior with Normative Feedback Interventions: A Field Experiment on Curbside Recycling. Basic Appl. Soc. Psych. 1999, 21, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, J.R.; Nielsen, J.M.; McCarlnielsen, J. Recycling as Altruistic Behavior: Normative and Behavioral Strategies to Expand Participation in a Community Recycling Program. Environ. Behav. 1991, 23, 195–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollen, S.; Rimal, R.N.; Ruiter, R.A.C.; Kok, G. Healthy and Unhealthy Social Norms and Food Selection. Findings from a Field-Experiment. Appetite 2013, 65, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorndike, A.N.; Riis, J.; Levy, D.E. Social Norms and Financial Incentives to Promote Employees’ Healthy Food Choices: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Prev. Med. (Baltim) 2016, 86, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, C.R.; Niculescu, M.; Just, D.R.; Kelly, M.P. Shopper Marketing Nutrition Interventions: Social Norms on Grocery Carts Increase Produce Spending without Increasing Shopper Budgets. Prev. Med. Rep. 2015, 2, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, D.T.; Prentice, D.A. Changing Norms to Change Behavior. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2016, 67, 339–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapinski, M.K.; Maloney, E.K.; Braz, M.; Shulman, H.C. Testing the Effects of Social Norms and Behavioral Privacy on Hand Washing: A Field Experiment. Hum. Commun. Res. 2013, 39, 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfattheicher, S.; Strauch, C.; Diefenbacher, S.; Schnuerch, R. A Field Study on Watching Eyes and Hand Hygiene Compliance in a Public Restroom. Ulm University, Ulm, Germany. Unpublished work. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Paluck, E.L.; Shepherd, H.; Aronow, P.M. Changing Climates of Conflict: A Social Network Experiment in 56 Schools. PNAS 2016, 113, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahlou, S. Installation Theory: The Societal Construction and Regulation of Behaviour; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, K.Z. Intention, Will and Need (1st ed. 1926). In A Kurt Lewin Reader. The Complete Social Scientist; Gold, M., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1999; pp. 83–115. [Google Scholar]

- Sherif, M.M. The Psychology of Social Norms; Octagon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Asch, S.E. Social Psychology; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Asch, S.E. Opinions and Social Pressure. Sci. Am. 1955, 193, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, F.H. Social Psychology. Psychol. Bull. 1920, 17, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateson, M.; Callow, L.; Holmes, J.R.; Redmond Roche, M.L.; Nettle, D. Do Images of “watching Eyes” Induce Behaviour That Is More pro-Social or More Normative? A Field Experiment on Littering. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluck, E.L. Reducing Intergroup Prejudice and Conflict Using the Media: A Field Experiment in Rwanda. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 96, 574–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluck, E.L.; Shepherd, H. The Salience of Social Referents: A Field Experiment on Collective Norms and Harassment Behavior in a School Social Network. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 103, 899–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gidycz, C.A.; Orchowski, L.M.; Berkowitz, A.D. Preventing Sexual Aggression among College Men: An Evaluation of a Social Norms and Bystander Intervention Program. Violence Against Women 2011, 17, 720–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bewick, B.M.; West, R.M.; Barkham, M.; Mulhern, B.; Marlow, R.; Traviss, G.; Hill, A.J. The Effectiveness of a Web-Based Personalized Feedback and Social Norms Alcohol Intervention on United Kingdom University Students: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chernoff, R.A.; Davison, G.C. An Evaluation of a Brief HIV/AIDS Prevention Intervention for College Students Using Normative Feedback and Goal Setting. AIDS Educ. Prev. 2005, 17, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mccoy, S.I.; Fahey, C.; Rao, A.; Kapologwe, N.; Njau, P.F.; Bautista-Arredondo, S. Pilot Study of a Multi-Pronged Intervention Using Social Norms and Priming to Improve Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy and Retention in Care among Adults Living with HIV in Tanzania. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celio, M.A.; Lisman, S.A. Examining the Efficacy of a Personalized Normative Feedback Intervention to Reduce College Student Gambling. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 2014, 62, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neighbors, C.; Rodriguez, L.M.; Rinker, D.V.; Gonzales, R.G.; Agana, M.; Tackett, J.L.; Foster, D.W. Efficacy of Personalized Normative Feedback as a Brief Intervention for College Student Gambling: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 83, 500–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Reno, R.R.; Kallgren, C.A. A Focus Theory of Normative Conduct: Recycling the Concept of Norms to Reduce Littering in Public Places. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Aarts, H.; Dijksterhuis, A. The Silence of the Library: Environment, Situational Norm, and Social Behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapinski, M.; Rimal, R. An Explication of Social Norms. Commun. Theory 2005, 15, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, N.J.; Cialdini, R.B.; Griskevicius, V. A Room with a Viewpoint: Using Social Norms to Motivate Environmental Conservation in Hotels. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Allcott, H. Social Norms and Energy Conservation. J. Public Econ. 2011, 95, 1082–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, M.E.; Lee, C.M.; Neighbors, C. Web-Based Intervention to Change Perceived Norms of College Student Alcohol Use and Sexual Behavior on Spring Break. Addict. Behav. 2014, 39, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolan, J.M.; Schultz, P.W.; Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J.; Griskevicius, V. Normative Social Influence Is Underdetected. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 34, 913–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cialdini, R. Crafting Normative Messages to Protect the Environment. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2003, 12, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schultz, P.W.; Nolan, J.M.; Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J.; Griskevicius, V. The Constructive, Destructive, and Reconstructive Power of Social Norms: Research Article. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, A.S.; Rogers, T. Descriptive Social Norms and Motivation to Vote: Everybody’s Voting and so Should You. J. Polit. 2009, 71, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, R.P.; Mortensen, C.R.; Cialdini, R.B. Bodies Obliged and Unbound: Differentiated Response Tendencies for Injunctive and Descriptive Social Norms. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 100, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabry, A.; Turner, M.M. Do Sexual Assault Bystander Interventions Change Men’s Intentions? Applying the Theory of Normative Social Behavior to Predicting Bystander Outcomes. J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolcini, M.M.; Catania, J.A.; Harper, G.W.; Watson, S.E.; Ellen, J.M.; Towner, S.L. Norms Governing Urban African American Adolescents’ Sexual and Substance-Using Behavior. J. Adolesc. 2013, 36, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Demaine, L.J.; Sagarin, B.J.; Barrett, D.W.; Winter, P.L. Managing Social Norms for Persuasive Impact. Soc. Influ. 2006, 1, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, D.A.; Miller, D.T. Pluralistic Ignorance and Alcohol Use on Campus: Some Consequences of Misperceiving the Social Norm. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 64, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valente, T.W.; Pumpuang, P. Identifying Opinion Leaders to Promote Behavior Change. Heal. Educ. Behav. 2007, 34, 881–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramsky, T.; Devries, K.; Kiss, L.; Nakuti, J.; Kyegombe, N.; Starmann, E.; Cundill, B.; Francisco, L.; Kaye, D.; Musuya, T.; et al. Findings from the SASA! Study: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial to Assess the Impact of a Community Mobilization Intervention to Prevent Violence against Women and Reduce HIV Risk in Kampala, Uganda. BMC Med. 2014, 12, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, D.M.; Lutes, L.D.; Littlewood, K.; DiNatale, E.; Hambidge, B.; Schulman, K. EMPOWER: A Randomized Trial Using Community Health Workers to Deliver a Lifestyle Intervention Program in African American Women with Type 2 Diabetes: Design, Rationale, and Baseline Characteristics. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2013, 36, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, R.F.; McAneney, H.; Davis, M.; Tully, M.A.; Valente, T.W.; Kee, F. “Hidden” Social Networks in Behavior Change Interventions. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 513–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, D.J.; Hogg, M.A.; White, K.M. Attitude-Behavior Relations: Social Indentity and Group Membership. In Attitudes, Behavior, and Social Context: The Role of Norms and Group Membership; Terry, D.J., Hogg, M.A., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 67–94. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J. An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Austin, W.G., Worchel, S., Eds.; Brooks-Cole: Monterey, CA, USA, 1979; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallsworth, M.; Chadborn, T.; Sallis, A.; Sanders, M.; Berry, D.; Greaves, F.; Clements, L.; Davies, S.C. Provision of Social Norm Feedback to High Prescribers of Antibiotics in General Practice: A Pragmatic National Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 1743–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolcini, M.M.; Harper, G.W.; Boyer, C.B.; Watson, S.E.; Anderson, M.; Pollack, L.M.; Chang, J.Y. Preliminary Findings on a Brief Friendship-Based HIV/STI Intervention for Urban African American Youth: Project ÒRÉ. J. Adolesc. Health 2008, 42, 629–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haylock, L.; Cornelius, R.; Malunga, A.; Mbandazayo, K. Shifting Negative Social Norms Rooted in Unequal Gender and Power Relationships to Prevent Violence against Women and Girls. Gend. Dev. 2016, 24, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, K.J.; Subašić, E.; Tindall, K. The Problem of Behaviour Change: From Social Norms to an Ingroup Focus. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2015, 9, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henry, D.B. Changing Classroom Social Settings Through Attention to Norms. In Toward Positive Youth Development: Transforming Schools and Community Programs; Shinn, M., Hirokazu, Y., Eds.; Oxford Scholarship Online: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.A.; Heiman, J.R.; Menczer, F. A Role for Network Science in Social Norms Intervention. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 51, 2217–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michie, S.; Richardson, M.; Johnston, M.; Abraham, C.; Francis, J.; Hardeman, W.; Eccles, M.P.; Cane, J.; Wood, C.E. The Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy (v1) of 93 Hierarchically Clustered Techniques: Building an International Consensus for the Reporting of Behavior Change Interventions. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 46, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michie, S.; Wood, C.E.; Johnston, M.; Abraham, C.; Francis, J.J.; Hardeman, W. Behaviour Change Techniques: The Development and Evaluation of a Taxonomic Method for Reporting and Describing Behaviour Change Interventions (a Suite of Five Studies Involving Consensus Methods, Randomised Controlled Trials and Analysis of Qualitative Da. Health Technol. Assess. (Rockv) 2015, 19, 1–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, A.K.; Warner, L.A. Promoting Behavior Change Using Social Norms: Applying a Community Based Social Marketing Tool to Extension Programming. J. Ext. 2015, 53, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Okoli, C.; Schabram, K. A Guide to Conducting a Systematic Literature Review of Information Systems Research. Work. Pap. Inf. Syst. 2010, 10, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littell, J.H.; Corcoran, J.; Pillai, V.K. Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater Reliability: The Kappa Statistic. Biochem. Medica 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.; Group, T.P. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta- Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e100097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, H.; Valentin, D. Multiple Correspondence Analysis. In Encyclopedia of Measurement and Statistics; Salkind, N., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, J.J. The Neglected 95%: Why American Psychology Needs to Become Less American. Am. Psychol. 2008, 63, 602–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, J.; Heine, S.J.; Norenzayan, A. The Weirdest People in the World? Behav. Brain Sci. 2010, 33, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brudermann, T.; Bartel, G.; Fenzl, T.; Seebauer, S. Eyes on Social Norms: A Field Study on an Honor System for Newspaper Sale. Theory Decis. 2015, 79, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wally, C.M.; Cameron, L.D. A Randomized-Controlled Trial of Social Norm Interventions to Increase Physical Activity. Ann. Behav. Med. 2017, 51, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suchman, L.A. Plans and Situated Actions. The Problem of Human-Machine Communication; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Lave, J. Cognition in Practice: Mind, Mathematics and Culture in Everyday Life; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, G.F.; Williams, A.; Moore, L.; Murphy, S. An Exploratory Cluster Randomised Trial of a University Halls of Residence Based Social Norms Marketing Campaign to Reduce Alcohol Consumption among 1st Year Students. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahlou, S.; Boesen-Mariani, S.; Franks, B.; Guelinckx, I. Increasing Water Intake of Children and Parents in the Family Setting: A Randomized, Controlled Intervention Using Installation Theory. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 66, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- DeJong, W. Social Norms Marketing Campaigns to Reduce Campus Alcohol Problems. Health Commun. 2010, 25, 615–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, J.E.; Peisner, W. RECOGNIZE: A Social Norms Campaign to Reduce Rumor Spreading in a Junior High School. Prof. Sch. Couns. 2009, 12, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, S.C.; Earle, A.M.; LaBrie, J.W.; Smith, D.J. PNF 2.0? Initial Evidence That Gamification Can Increase the Efficacy of Brief, Web-Based Personalized Normative Feedback Alcohol Interventions. Addict. Behav. 2016, 67, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neighbors, C.; Larimer, M.E.; Lewis, M.A. Targeting Misperceptions of Descriptive Drinking Norms: Efficacy of a Computer-Delivered Personalized Normative Feedback Intervention. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 72, 434–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latkin, C.; Donnell, D.; Liu, T.-Y.; Davey-Rothwell, M.; Celentano, D.; Metzger, D. The Dynamic Relationship between Social Norms and Behaviors: The Results of an HIV Prevention Network Intervention for Injection Drug Users. Addiction 2013, 108, 934–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurasek, A.M.; Borsari, B.; Magill, M.; Mastroleo, N.R.; Hustad, J.T.P.; O’Leary Tevyaw, T.; Barnett, N.P.; Kahler, C.W.; Monti, P.M.; Tevyaw, T.O.; et al. Descriptive Norms and Expectancies as Mediators of a Brief Motivational Intervention for Mandated College Students Receiving Stepped Care for Alcohol Use. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2015, 29, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogro-Wilson, C.; Allen, E.; Cavallucci, C. A Brief High School Prevention Program to Decrease Alcohol Usage and Change Social Norms. Soc. Work Res. 2017, 41, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, B.; Manley, D.; Mendoza, R. The Impact of an Alcohol Education Program Using Social Norming. Ky. Nurse 2013, 61, 6–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Agha, S.; Van Rossem, R. Impact of a School-Based Peer Sexual Health Intervention on Normative Beliefs, Risk Perceptions, and Sexual Behavior of Zambian Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2004, 34, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balvig, F.; Holmberg, L. The Ripple Effect: A Randomized Trial of a Social Norms Intervention in a Danish Middle School Setting. J. Scand. Stud. Criminol. Crime Prev. 2011, 12, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.P.; Houck, J.M.; Rowell, L.N.; Benson, J.G.; Smith, D.C. Brief Motivational Interviewing and Normative Feedback for Adolescents: Change Language and Alcohol Use Outcomes. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2016, 65, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewin, K.Z. Forces Behind Food Habits and Methods of Change. Bull. Natl. Res. Counc. 1943, 108, 35–65. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, M.A.; Maisto, S.A.; Rice, S.L.; Carey, K.B. Development of a Face-to-Face Injunctive Norms Brief Motivational Intervention for College Drinkers and Preliminary Outcomes. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2015, 29, 825–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamby, A.; Brinberg, D.; Jaccard, J. A Conceptual Framework of Narrative Persuasion. J. Media Psychol. 2016, 30, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.; Maio, G.; Smith-McClallen, A. Communication and Attitude Change: Causes, Processes and Effects. In Handbook of Attitudes; Albarracin, D., Johnson, B., Zanna, M., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 617–670. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, J. Actual Minds. Possible Worlds; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kareev, Y. Seven (Indeed, plus or Minus Two) and the Detection of Correlations. Psychol. Rev. 2000, 107, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaeli, M.; Spiro, D. From Peer Pressure to Biased Norms. Am. Econ. J. Microecon. 2017, 9, 152–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassman, T.; Dodd, V.; Kenzik, K.; Miller, M.E.; Sheu, J.-J. Social Norms vs. Risk Reduction Approaches to 21st Birthday Celebrations. Am. J. Heal. Educ. 2010, 41, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.A.; Sheng, X.; Perry, A.S.; Stevenson, D.A. Activity and Participation in Children with Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 36, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harries, T.; Rettie, R.; Studley, M.; Burchell, K.; Chambers, S. Is Social Norms Marketing Effective? A Case Study in Domestic Electricity Consumption. Eur. J. Mark. 2013, 47, 1458–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholly, K.; Katz, A.R.; Gascoigne, J.; Holck, P.S. Using Social Norms Theory to Explain Perceptions and Sexual Health Behaviors of Undergraduate College Students: An Exploratory Study. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 2005, 53, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elias-Lambert, N.; Black, B.M. Bystander Sexual Violence Prevention Program: Outcomes for High- and Low-Risk University Men. J. Interpers. Violence 2016, 31, 3211–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bewick, B.M.; Trusler, K.; Mulhern, B.; Barkham, M.; Hill, A.J. The Feasibility and Effectiveness of a Web-Based Personalised Feedback and Social Norms Alcohol Intervention in UK University Students: A Randomised Control Trial. Addict. Behav. 2008, 33, 1192–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bewick, B.M.; West, R.; Gill, J.; O’May, F.; Mulhern, B.; Barkham, M.; Hill, A.J. Providing Web-Based Feedback and Social Norms Information to Reduce Student Alcohol Intake: A Multisite Investigation. J. Med. Internet Res. 2010, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, H.W.; Linkenbach, J.W.; Lewis, M.A.; Neighbors, C. Effectiveness of Social Norms Media Marketing in Reducing Drinking and Driving: A Statewide Campaign. Addict. Behav. 2010, 35, 866–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluck, E. What’s in a Norm? Sources and Processes of Norm Change. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 96, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, J.O. Cultura Ciudadana y Homicidio En Bogotá. In Cultura Ciudadana en Bogotá: Nuevas Perspectivas; Secretaría de Cultura, Recreación y Deporte: Bogotá, Colombia, 2012; pp. 88–109. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, E. Regulación y Autorregulación En El Espacio Público. In Cultura Ciudadana en Bogotá: Nuevas Perspectivas; Secretaría de Cultura, Recreación y Deporte: Bogotá, Colombia, 2012; pp. 44–71. [Google Scholar]

- Murrain, H. Cultura Ciudadana Como Política Pública: Entre Indicadores y Arte. In Cultura Ciudadana en Bogotá: Nuevas Perspectivas; Secretaría de Cultura, Recreación y Deporte: Bogotá, Colombia, 2012; pp. 194–213. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, L. The Intuitive Psychologist and His Shortcomings: Distortions in the Attribution Process. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977; pp. 173–220. [Google Scholar]

- Nosulenko, V.N.; Samoylenko, E.S. Approche Systémique de l’analyse Des Verbalisations Dans Le Cadre de l’étude Des Processus Perceptifs et Cognitifs. Soc. Sci. Inf. 1997, 36, 223–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lossin, F.; Loder, A.; Staake, T. Energy Informatics for Behavioral Change: Increasing the Participation Rate in an IT-Based Energy Conservation Campaign Using Social Norms and Incentives. Comput. Sci. Res. Dev. 2016, 31, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.A.; Neighbors, C.; Lee, C.M.; Oster-Aaland, L. 21st Birthday Celebratory Drinking: Evaluation of a Personalized Normative Feedback Card Intervention. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2008, 22, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werch, C.E.; Pappas, D.M.; Carlson, J.M.; DiClemente, C.C.; Chally, P.S.; Sinder, J.A. Results of a Social Norm Intervention to Prevent Binge Drinking among First-Year Residential College Students. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 2000, 49, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, T.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Schuster, L.; Drennan, J.; Russell-Bennett, R.; Leo, C.; Gullo, M.J.; Connor, J.P. Differential Segmentation Responses to an Alcohol Social Marketing Program. Addict. Behav. 2015, 49, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, E.F.; Louis, W.R. Doing Democracy: The Social Psychological Mobilization and Consequences of Collective Action. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2013, 7, 173–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yamin, P. An Engaged Pedagogy of Everyday Life. Master’s Thesis, Goldsmiths College, University of London, London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Spijkerman, R.; Roek, M.A.E.; Vermulst, A.; Lemmers, L.; Huiberts, A.; Engels, R.C.M.E. Effectiveness of a Web-Based Brief Alcohol Intervention and Added Value of Normative Feedback in Reducing Underage Drinking: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2010, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocci, A. A Semidirective Interview Method to Analyze Behavioral Changes. Transp. Res. Rec. 2009, 2105, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henson, J.; Pearson, M.; Carey, K. Defining and Characterizing Differences in College Alcohol Intervention Efficacy: A Growth Mixture Modeling Application. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 83, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thombs, D.L.; Dotterer, S.; Olds, R.S.; Sharp, K.E.; Raub, C.G. A Close Look at Why One Social Norms Campaign Did Not Reduce Student Drinking. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 2004, 53, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamin, P.; Hobden, C. Practical Methods to Change Social Norms in Domestic Work; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, H.W.; Craig, D.W. A Successful Social Norms Campaign to Reduce Alcohol Misuse among College Student-Athletes. J. Stud. Alcohol 2006, 67, 880–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silk, K.J.; Perrault, E.K.; Nazione, S.A.; Pace, K.; Collins-Eaglin, J. Evaluation of a Social Norms Approach to a Suicide Prevention Campaign. J. Health Commun. 2017, 22, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.W.; Atkin, C.K.; Martell, D.; Allen, R.; Hembroff, L. A Social Judgment Theory Approach to Conducting Formative Research in a Social Norms Campaign. Commun. Theory 2006, 16, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.A.; Patrick, M.E.; Litt, D.M.; Atkins, D.C.; Kim, T.; Blayney, J.A.; Norris, J.; George, W.H.; Larimer, M.E. Randomized Controlled Trial of a Web-Delivered Personalized Normative Feedback Intervention to Reduce Alcohol-Related Risky Sexual Behavior among College Students. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 82, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, J.; Perkins, H.W.; Bauerle, J. Declining Negative Consequences Related to Alcohol Misuse among Students Exposed to a Social Norms Marketing Intervention on a College Campus. J. Am. Coll. Health 2008, 57, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toghianifar, N.; Sarrafzadegan, N.; Gharipour, M. Women’s Attitude toward Smoking: Effect of a Community-Based Intervention on Smoking-Related Social Norms. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2014, 12, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brent, D.A.; Lott, C.; Taylor, M.; Cook, J.; Rollins, K.; Stoddard, S.; Brent, D.A.; Lott, C.; Taylor, M.; Cook, J. Are Normative Appeals Moral Taxes? Evidence from a Field Experiment on Water Conservation; Working paper 2017-07; Department of Economics, Louisiana State University: Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, S.; Keller, A. Applying Social Norms Theory within Groups: Promising for High-Risk Drinking. NASPA J. 2007, 44, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, R.; Eberhardt, I.; Smeets, P. Financial Incentives Beat Social Norms: A Field Experiment on Retirement Information Search. SSRN Electron. J. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnum Photos. Profile of Robert Capa. Available online: https://pro.magnumphotos.com/C.aspx?VP3=CMS3&VF=MAGO31_9_VForm&ERID=24KL535353 (accessed on 23 September 2019).

- Bertholet, N.; Daeppen, J.-B.; Cunningham, J.A.; Burnand, B.; Gmel, G.; Gaume, J. Are Young Men Who Overestimate Drinking by Others More Likely to Respond to an Electronic Normative Feedback Brief Intervention for Unhealthy Alcohol Use? Addict. Behav. 2016, 63, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boen, F.; Van Hoecke, A.-S.; Smits, T.; Hurkmans, E.; Fransen, K.; Seghers, J. Portraying Role Models to Promote Stair Climbing in a Public Setting: The Effect of Matching Sex and Age. KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium. Unpublished work. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland, M.J.; Hultgren, B.; Varvil-Weld, L.; Mallett, K.A.; Turrisi, R.; Abar, C.C. Moderation of a Parent-Based Intervention on Transitions in Drinking: Examining the Role of Normative Perceptions and Attitudes among High- and Low-Risk First-Year College Students. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2013, 37, 1587–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.E.; Carey, K.B.; Sliwinski, M.J. Mailed Personalized Normative Feedback as a Brief Intervention for At-Risk College Drinkers. J. Stud. Alcohol 2002, 63, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.E.; Kirouac, M.; Lewis, M.A.; Witkiewitz, K.; Carey, K.B. Randomized Controlled Trial of Web-Based Decisional Balance Feedback and Personalized Normative Feedback for College Drinkers. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2014, 75, 982–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cunningham, J.A.; Wong, H.T.A. Assessing the Immediate Impact of Normative Drinking Information Using an Immediate Post-Test Randomized Controlled Design: Implications for Normative Feedback Interventions? Addict. Behav. 2013, 38, 2252–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeJong, W.; Schneider, S.K.; Towvim, L.G.; Murphy, M.J.; Doerr, E.E.; Simonsen, N.R.; Mason, K.E.; Scribner, R.A. A Multisite Randomized Trial of Social Norms Marketing Campaigns to Reduce College Student Drinking. J. Stud. Alcohol 2006, 67, 868–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doumas, D.M.; Hannah, E. Preventing High-Risk Drinking in Youth in the Workplace: A Web-Based Normative Feedback Program. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2008, 34, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doumas, D.M.; Haustveit, T.; Coll, K.M. Reducing Heavy Drinking among First Year Intercollegiate Athletes: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Web-Based Normative Feedback. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2010, 22, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doumas, D.M.; Workman, C.; Smith, D.; Navarro, A. Reducing High-Risk Drinking in Mandated College Students: Evaluation of Two Personalized Normative Feedback Interventions. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2011, 40, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartwell, C.J.; Campion, M.A. Getting on the Same Page: The Effect of Normative Feedback Interventions on Structured Interview Ratings. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 757–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, L.C.; Carr, P.B.; Walton, G.M. Normative Appeals Are More Effective When They Invite People to Work Together Toward a Common Cause. Stanford University, Stanford. U.S. Unpublished work. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Koeneman, M.A.; Chorus, A.; Hopman-Rock, M.; Chinapaw, M.J.M. A Novel Method to Promote Physical Activity among Older Adults in Residential Care: An Exploratory Field Study on Implicit Social Norms. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulik, J.A.; Butler, H.A.; Gerrard, M.; Gibbons, F.X.; Mahler, H.I.M. Social Norms Information Enhances the Efficacy of an Appearance-Based Sun Protection Intervention. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrie, J.W.; Hummer, J.F.; Huchting, K.K.; Neighbors, C. A Brief Live Interactive Normative Group Intervention Using Wireless Keypads to Reduce Drinking and Alcohol Consequences in College Student Athletes. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2009, 28, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.A.; Neighbors, C. Who Is the Typical College Student? Implications for Personalized Normative Feedback Interventions. Addict. Behav. 2006, 31, 2120–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lojewski, R.; Rotunda, R.J.; Arruda, J.E. Personalized Normative Feedback to Reduce Drinking among College Students: A Social Norms Intervention Examining Gender-Based versus Standard Feedback. J. Alcohol Drug Educ. 2010, 54, 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Mattern, J.L.; Neighbors, C. Social Norms Campaigns: Examining the Relationship between Changes in Perceived Norms and Changes in Drinking Levels. J. Stud. Alcohol 2004, 65, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollen, S.; Rimal, R.N.; Ruiter, R.A.C.; Jang, S.A.; Kok, G. Intervening or Interfering? The Influence of Injunctive and Descriptive Norms on Intervention Behaviours in Alcohol Consumption Contexts. Psychol. Health 2013, 28, 561–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, M.T.; Oskrochi, R.; Foxcroft, D.R. Personalised Normative Feedback for Preventing Alcohol Misuse in University Students: Solomon Three-Group Randomised Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e44120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neighbors, C.; Lewis, M.A.; Atkins, D.C.; Jensen, M.M.; Walter, T.; Fossos, N.; Lee, C.M.; Larimer, M.E. Efficacy of Web-Based Personalized Normative Feedback: A Two-Year Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 78, 898–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neighbors, C.; Jensen, M.; Tidwell, J.; Walter, T.; Fossos, N.; Lewis, M.A. Social-Norms Interventions for Light and Nondrinking Students. Gr. Process. Intergr. Relations 2011, 14, 651–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neighbors, C.; Lewis, M.A.; Bergstrom, R.L.; Larimer, M.E. Being Controlled by Normative Influences: Self-Determination as a Moderator of a Normative Feedback Alcohol Intervention. Heal. Psychol. 2006, 25, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, E.R.; Parast, L.; Marshall, G.N.; Schell, T.L.; Neighbors, C. A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial for a Web-Based Personalized Normative Feedback Alcohol Intervention for Young Adult Veterans. Alcohol. Exp. Res. 2016, 40, 68A. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, H.W.; Craig, D.W.; Perkins, J.M. Using Social Norms to Reduce Bullying: A Research Intervention among Adolescents in Five Middle Schools. Gr. Process. Intergr. Relations 2011, 14, 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, A.E.; Aiken, L.S. Correcting Injunctive Norm Misperceptions Motivates Behavior Change: A Randomized Controlled Sun Protection Intervention. Health Psychol. 2013, 32, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, D.W.; Wood, M.D. A Randomized Test of a Small-Group Interactive Social Norms Intervention. J. Am. Coll. Health 2008, 57, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridout, B.; Campbell, A. Using Facebook to Deliver a Social Norm Intervention to Reduce Problem Drinking at University. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2014, 33, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, P.W.; Tyra, A. Two Field Studies of Normative Beliefs and Environmental Behavior. California State University, San Marcos. U.S. Unpublished work. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, P.W.; Rendón, T.; Göckeritz, S.; Hübner, G.; Corral-Verdugo, V.; Ando, K. Normative Social Influence Transcends Culture, But Detecting It Is Culture Specific. California State University, San Marcos. U.S. Unpublished work. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Scribner, R.A.; Theall, K.P.; Mason, K.; Simonsen, N.; Schneider, S.K.; Towvim, L.G.; Dejong, W. Alcohol Prevention on College Campuses: The Moderating Effect of the Alcohol Environment on the Effectiveness of Social Norms Marketing Campaigns. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2011, 72, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stamper, G.A.; Smith, B.H.; Gant, R.; Bogle, K.E. Replicated Findings of an Evaluation of a Brief Intervention Designed to Prevent High-Risk Drinking among First-Year College Students: Implications for Social Norming Theory. J. Alcohol Drug Educ. 2004, 48, 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Steffian, G. Correction of Normative Misperceptions: An Alcohol Abuse Prevention Program. J. Drug Educ. 1999, 29, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, J.; Hancock, L.; Wattenmaker McGann, A.; Alshagra, M.; Ericson, R.; Niazi, Z.; Dick, D.M.; Adkins, A. Evaluating the Effect of a Campus-Wide Social Norms Marketing Intervention on Alcohol Use Perceptions, Consumption, and Blackouts. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 2017, 66, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.J.; Vlaev, I.; Maltby, J.; Brown, G.D.A.; Wood, A.M. Improving Social Norms Interventions: Rank-Framing Increases Excessive Alcohol Drinkers’ Information-Seeking. Heal. Psychol. 2015, 34, 1200–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thombs, D.L.; Olds, R.S.; Osborn, C.J.; Casseday, S.; Glavin, K.; Berkowitz, A.D. Outcomes of a Technology-Based Social Norms Intervention to Deter Alcohol Use in Freshman Residence Halls. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 2007, 55, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegs, C.; Creanga, A.A.; Galavotti, C.; Wamalwa, E. Community Dialogue to Shift Social Norms and Enable Family Planning: An Evaluation of the Family Planning Results Initiative in Kenya. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, M. Misperceptions of Social Norms about Tax Compliance: From Theory to Intervention. J. Econ. Psychol. 2005, 26, 862–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Countries | Target Behaviors | Type of Participants | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Frequency | Frequency | |||

| US | 63 | Alcohol consumption | 48 | Students | 58 |

| UK | 7 | Health behaviors | 14 | Residents | 14 |

| Netherlands | 3 | Pro-environmental * | 13 | Employees | 4 |

| Australia | 2 | Sexual health/HIV | 5 | Drinkers-drug users | 4 |

| Canada | 2 | Bullying/harassment behavior | 4 | Passers-by | 3 |

| Colombia | 2 | Gambling | 2 | Shoppers | 2 |

| Germany | 2 | Tax and retirement | 2 | Users of public restrooms | 2 |

| Switzerland | 2 | Counselling service use | 1 | Cyclists | 1 |

| Austria | 1 | Ethical behavior | 1 | Doctors | 1 |

| Denmark | 1 | Rating of interviews | 1 | Patients | 1 |

| Ecuador | 1 | Use of pedestrian crossings | 1 | Pension fund participants | 1 |

| Iran | 1 | Taxpayers | 1 | ||

| Kenya | 1 | ||||

| Multiple countries | 1 | - | - | ||

| Poland | 1 | ||||

| Tanzania | 1 | ||||

| Zambia | 1 | ||||

| Layer | Mechanisms (Application in Sample) | Common Applications in Sample |

|---|---|---|

| Social | Transmitting group summary information messages (situated–remote) | Messages summarizing normative information about a group, for example after completing survey or through email, or in promotional materials such as fliers, letters posters, signs, stickers and adds |

| Exposure to behaviour and opinions (situated–remote) | Face-to-face interaction, videos, staring eyes in walls, drama skits, public rejections by social referents and public figures, as well as public demonstrations | |

| Generating discussions about normative information (situated) | Sessions with face-to-face discussions among participants | |

| Law and policy enforcement (situated) | Direct enforcement and control in specific contexts | |

| Mutual regulation (situated) | Creating situations or distributing objects that promote mutual regulation among participants, such as mime-artists, cards or whistles | |

| Social support (situated) | Creating digital forums to discuss normative information and provide mutual support | |

| Psychological | Providing factual/context information (situated–remote) | Information about risks/benefits of engaging in target behavior in signs, leaflets and posters, and context information in leaflets, fliers, or through digital media |

| Providing tips and guides for action / goal setting (situated–remote) | Steps and goals for engaging in target behaviors in leaflets, fliers, or through digital media | |

| Generating discussions among participants (indirect) | Face-to-face sessions to discuss information relevant to target behaviors | |

| Generating training/skills building sessions (remote) | Face-to-face sessions to train and teach skills to participants and relevant referents | |

| Creating commitments to action (remote) | Contracts or symbolic actions to generate behavior-relevant commitments | |

| Providing incentives (remote) | Applying financial incentives or penalties for engaging in target behaviors | |

| Providing psychological therapy (remote) | Regular therapy sessions for participants | |

| Physical | Modifying environments (situated) | Fixing promotional materials (such as posters or signs) or providing objects that support target behaviors (such as bikes, water bottles or whistles) |

| Distributing papers/objects (situated–remote) | Distributing promotional materials (such as fliers or t-shirts) or objects that support target behaviors (such as bikes, water bottles or whistles) | |

| Generating interactions with digital platforms (remote) | Use of digital platforms (such as computers and smart phones) to distribute intervention materials and information |

| Characteristic | Group 1 (component 1 +) | Group 2 (component 1 -) |

|---|---|---|

| Dimensions | Remote Group summary intervention | Situated Exposure to behaviors and opinions |

| Intervention mechanisms | Digital platforms | Discussions among participants (about normative and non-normative information) Providing context information Providing tips and guides for action Modifying environments Distributing papers and objects |

| Target behaviors | Alcohol consumption Health behaviors | Pro-environmental behaviors |

| Participant types | Students Employees | Residents |

| Period of publication | 2001–2010 2011–2017 | 1991–2000 |

| Number of participants | Less than 200 Between 200 and 500 | Between 500 and 1000 More than 1000 |

| Studies with Effects on Behavior Linked to Social Norms (Excluding Self-Reported Measures) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |

| Remote only | 3 | 2 |

| Situated only | 21 | 1 |

| Both | 1 | 0 |

| TOTAL | 25 | 3 |

| Situated Interventions | |

| Group summary information (Q. II) | Exposure to behaviors and opinions (Q. I) |

| Create marketing material with group summary information to be distributed in the same context where the target behavior happens [24] Include credible and strategic messages with the rates of prevalence and support that the target behavior (or related ones) have in a certain population (i.e., if you want to reduce drinking rates among students, show how most of them drink less, or that more disapproved heavy drinking, than usually thought [129]) Choose strategically the marketing materials that are more likely to be seen and remembered by the highest possible number of participants (i.e., posters, fliers, signs, stickers, adds, etc. [111,130,131]) | Create actions and/or provide objects in the same context in which the behavior happens that make visible (see [35,85,111]):

|

| Remote Interventions | |

| Group summary information (Q. III) | Exposure to behaviors and opinions (Q. IV) |

| Create marketing materials with group summary information to be distributed away from the context where the behavior happens (see guidelines in quadrant I) Benefiting from easier access and targetability, consider:

| Create actions and/or provide objects away from the context in which the behavior happens to make visible [90,92]:

|

| Other Support Mechanisms | |

| Depending on the intervention contexts and target behaviors, as well as the available resources, consider complementing the intervention with mechanisms such as: Providing objects or modifying physical environments in ways that make the target behavior easier or more likely (such as bikes or water bottles [17,85]) Arranging external law and policy enforcement of the target behavior, or creating situations and providing materials that allow participants to regulate each other [6,134]; this can be enforced by policing personnel or by fellow citizens through the “vigilante effect” [27] (pp. 140–144) Creating digital and other forums to discuss normative information and provide mutual support [85] Providing factual and context information, and tips and guides for action [37,135] Generating discussions between participants about any aspects of the target behavior and change, including but not limited to the normative ones [35,98,129] Implementing training and skills building processes that support the target behavior [35,93,136] Setting goals or creating commitments to action (such as contracts or symbolic vaccination activities [6,95]) Providing financial incentives or penalties compatible with the target behavior [6,21,137] In special cases, providing psychological therapy [96] | |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yamin, P.; Fei, M.; Lahlou, S.; Levy, S. Using Social Norms to Change Behavior and Increase Sustainability in the Real World: a Systematic Review of the Literature. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5847. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su11205847

Yamin P, Fei M, Lahlou S, Levy S. Using Social Norms to Change Behavior and Increase Sustainability in the Real World: a Systematic Review of the Literature. Sustainability. 2019; 11(20):5847. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su11205847

Chicago/Turabian StyleYamin, Paulius, Maria Fei, Saadi Lahlou, and Sara Levy. 2019. "Using Social Norms to Change Behavior and Increase Sustainability in the Real World: a Systematic Review of the Literature" Sustainability 11, no. 20: 5847. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su11205847