Sustainability of Government Microblog in China: Exploring Social Factors on Mobile Government Microblog Continuance

Abstract

:1. Introduction

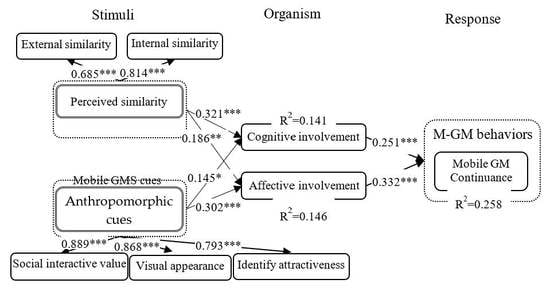

- how citizens’ perceived similarity (including external similarity and internal similarity) and anthropomorphic cues (including social interactive value, visual appearance and identify attractiveness) influence their cognitive and affective involvement?

- what is the role of citizens’ cognitive and affective involvement in shaping their continuance intention of mobile government microblog?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) Framework

2.2. Social Response Theory

2.3. Perceived Similarity

3. Research Model and Hypotheses

3.1. Perceived Similarity

3.2. Anthropomorphic Cues

3.3. Involvement

4. Methodology

4.1. Instrument

4.2. Data Collection

5. Data Analysis and Results

5.1. Measurement Model

5.2. Structural Model

6. Discussion

6.1. Summary of Findings

6.2. Limitation and Future Work

7. Conclusions

7.1. Theoretical Implications

7.2. Practical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Scales and Items

Appendix B

| Factor | SIV | IS | ES | MGC | AIN | CIN | VA | IA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIV1 | 0.799 | 0.052 | 0.000 | 0.120 | 0.090 | 0.000 | 0.242 | 0.133 |

| SIV2 | 0.797 | 0.027 | −0.018 | 0.021 | 0.041 | 0.016 | 0.314 | 0.183 |

| SIV3 | 0.847 | 0.065 | 0.003 | 0.058 | 0.025 | 0.028 | 0.204 | 0.153 |

| SIV4 | 0.742 | 0.100 | 0.046 | 0.053 | 0.158 | 0.117 | 0.153 | 0.198 |

| IS1 | 0.087 | 0.841 | 0.026 | 0.098 | 0.008 | 0.064 | −0.024 | 0.050 |

| IS2 | 0.027 | 0.901 | 0.035 | 0.061 | −0.011 | 0.063 | −0.002 | 0.119 |

| IS3 | 0.039 | 0.861 | 0.040 | 0.080 | 0.009 | 0.053 | −0.009 | 0.106 |

| IS4 | 0.057 | 0.784 | 0.072 | 0.022 | 0.147 | 0.123 | 0.080 | 0.030 |

| ES1 | 0.011 | 0.078 | 0.918 | 0.097 | 0.046 | 0.125 | 0.007 | 0.010 |

| ES2 | 0.021 | 0.051 | 0.896 | 0.145 | 0.105 | 0.096 | −0.016 | 0.051 |

| ES3 | −0.012 | 0.037 | 0.911 | 0.078 | 0.055 | 0.093 | −0.042 | 0.046 |

| MGC1 | 0.085 | 0.097 | 0.112 | 0.857 | 0.177 | 0.132 | 0.082 | 0.124 |

| MGC2 | 0.082 | 0.057 | 0.145 | 0.862 | 0.169 | 0.176 | 0.033 | 0.103 |

| MGC3 | 0.068 | 0.121 | 0.096 | 0.836 | 0.178 | 0.162 | 0.031 | 0.105 |

| AIN1 | 0.089 | 0.062 | 0.069 | 0.185 | 0.842 | 0.210 | 0.097 | 0.097 |

| AIN2 | 0.133 | 0.034 | 0.102 | 0.233 | 0.789 | 0.260 | 0.046 | 0.140 |

| AIN3 | 0.080 | 0.054 | 0.063 | 0.139 | 0.857 | 0.166 | 0.053 | 0.120 |

| CIN1 | 0.012 | 0.083 | 0.093 | 0.163 | 0.201 | 0.848 | 0.033 | 0.085 |

| CIN2 | 0.047 | 0.141 | 0.131 | 0.205 | 0.246 | 0.809 | 0.039 | 0.092 |

| CIN3 | 0.075 | 0.105 | 0.125 | 0.111 | 0.160 | 0.852 | −0.038 | 0.060 |

| VA1 | 0.357 | −0.023 | −0.002 | 0.037 | 0.100 | 0.025 | 0.816 | 0.168 |

| VA2 | 0.410 | 0.029 | −0.020 | 0.056 | 0.085 | 0.011 | 0.769 | 0.224 |

| VA3 | 0.341 | 0.030 | −0.050 | 0.075 | 0.035 | −0.006 | 0.771 | 0.250 |

| IA1 | 0.234 | 0.121 | 0.067 | 0.177 | 0.183 | 0.080 | 0.170 | 0.803 |

| IA2 | 0.300 | 0.104 | 0.070 | 0.161 | 0.112 | 0.147 | 0.174 | 0.786 |

| IA3 | 0.208 | 0.144 | 0.006 | 0.053 | 0.101 | 0.051 | 0.273 | 0.756 |

| Eigen-values | 3.214 | 3.025 | 2.602 | 2.514 | 2.431 | 2.418 | 2.244 | 2.224 |

| Variance% | 12.360 | 11.634 | 10.008 | 9.668 | 9.350 | 9.302 | 8.629 | 8.552 |

| Cumulative% | 12.360 | 23.995 | 34.003 | 43.671 | 53.021 | 62.323 | 70.952 | 79.504 |

References

- Guo, J.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y. Key success factors for the launch of government social media platform: Identifying the formation mechanism of continuance intention. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 750–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Yang, S.; Chen, Y.; Long, Q.; Wei, J. Explaining and predicting mobile government microblogging services participation behaviors: A SEM-neural network method. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 39600–39611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zeng, X. Sustainability of government social media: A multi-analytic approach to predict citizens’ mobile government microblog continuance. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- CNNIC 44th Statistical Survey Report on Internet Development in China. Available online: http://www.cnnic.net.cn/ (accessed on 12 September 2019).

- Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Chen, Y.; Yao, J. Effects of perceived online–offline integration and internet censorship on mobile government microblogging service continuance: A gratification perspective. Gov. Inf. Q. 2018, 35, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Hui, J.; Yao, J.; Chen, Y.; Wei, J. Perceived values on mobile GMS continuance: A perspective from perceived integration and interactivity. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 89, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K. Integrating cognitive antecedents into TAM to explain mobile banking behavioral intention: A SEM-neural network modeling. Inf. Syst. Front. 2019, 21, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K.; Al-Badi, A.; Rana, N.P.; Al-Azizi, L. Mobile applications in government services (mG-App) from user’s perspectives: A predictive modelling approach. Gov. Inf. Q. 2018, 35, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environment Psychology; MIT: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, Y. Don’t blame the computer: When self-disclosure moderates the self-serving bias. J. Consum. Psychol. 2003, 13, 125–137. [Google Scholar]

- Bitner, M.J. Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.H.; Chih, W.H.; Liou, D.K.; Hwang, L.R. The influence of web aesthetics on customers’ PAD. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 36, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Chan, J.; Tan, B.C.Y.; Wei, S.C. Effects of interactivity on website involvement and purchase intention. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2010, 11, 34–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, J.U.; Rahman, Z. The impact of online brand community characteristics on customer engagement: An application of Stimulus-Organism-Response paradigm. Telemat. Inf. 2017, 34, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, B.; Verma, R.; Kunz, W. How to transform consumers into fans of your brand. J. Serv. Manag. 2012, 23, 344–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Vega, R.; Taheri, B.; Farrington, T.; O’Gorman, K. On being attractive, social and visually appealing in social media: The effects of anthropomorphic tourism brands on Facebook fan pages. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, J.-W.; Lin, C.-P. To stick or not to stick: The social response theory in the development of continuance intention from organizational cross-level perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 1963–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzakova, M.; Kwak, H.; Rocereto, J.F. When humanizing brands goes wrong: The detrimental effect of brand anthropomorphization amid product wrongdoings. J. Mark. 2013, 77, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, S.S.; Nass, C. Source orientation in human-computer interactionprogrammer, networker, or independent social actor. Commun. Res. 2000, 27, 683–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Rodríguez, L.; Cuadrado, I.; Navas, M. I will help you because we are similar: Quality of contact mediates the effect of perceived similarity on facilitative behaviour towards immigrants. Int. J. Psychol. 2017, 52, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Yan, Q.; Feng, G.C. Who will attract you? Similarity effect among users on online purchase intention of movie tickets in the social shopping context. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 40, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.C.; Huang, C.Y.; Hsu, C.T. A benefit-cost perspective of the consumer adoption of the mobile banking system. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2010, 29, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D. An overview (and underview) of research and theory within the attraction paradigm. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 14, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Malhotra, S. To adapt or not adapt: The moderating effect of perceived similarity in cross-cultural business partnerships. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2012, 36, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P. The impact of organizational efforts on consumer concerns in an online context. Inf. Manag. 2014, 51, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eroglu, S.A.; Machleit, K.A.; Davis, L.M. Empirical testing of a model of online store atmospherics and shopper responses. Psychol. Mark. 2003, 20, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.A.; Gretzel, U. Success factors for destination marketing web sites: A qualitative meta-analysis. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Consumer-company identification: A framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, T.; Bloemers, D. Exploring the cognitive and affective bases of online purchase intentions: A hierarchical test across product types. Electron. Commer. Res. 2018, 18, 537–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhou, S.; Cheng, X. Why do college students continue to use mobile learning? Learning involvement and self-determination theory. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2019, 52, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lennon, S.J.; Stoel, L. On-line product presentation: Effects on mood, perceived risk, and purchase intention. Psychol. Mark. 2010, 22, 695–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perse, E.M. Implications of cognitive and affective involvement for channel changing. J. Commun. 2010, 48, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcmillan, S.J.; Hwang, J.S.; Lee, G. Effects of structural and perceptual factors on attitudes toward the website. J. Advert. Res. 2003, 43, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, L.; Maya, S.R.D. The role of affiliation, attractiveness and personal connection in consumer-company identification. Eur. J. Mark. 2013, 47, 154–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding information systems continuance: An expectation-confirmation model. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D.; Boudreau, M.-C. Structural equation modeling and regression: Guidelines for research practice. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2000, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, L.-Y.; Jaafar, N.I.; Ainin, S. The effects of Facebook browsing and usage intensity on impulse purchase in f-commerce. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 78, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Lu, Y.; Chau, P.Y.K.; Gupta, S. Role of channel integration on the service quality, satisfaction, and repurchase intention in a multi-channel (online-cum-mobile) retail environment. Int. J. Mob. Commun. 2017, 15, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.; Organ, D. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.G.; Saraf, N.; Hu, Q.; Xue, Y.J. Assimilation of enterprise systems: The effect of institutional pressures and the mediating role of top management. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measure | Item | Number (N = 428) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 212 | 49.5% |

| Female | 216 | 50.5% | |

| Age | <18 years | 26 | 6.1% |

| >19 and ≤30 years | 172 | 40.2% | |

| >31 and ≤45 years | 144 | 33.6% | |

| >46 and ≤59 years | 75 | 17.5% | |

| ≥60 years | 11 | 2.6% | |

| Education | Middle school or below | 24 | 5.6% |

| High school | 49 | 11.4% | |

| 3-Year college | 118 | 27.6% | |

| 4-Year university | 202 | 47.2% | |

| Master or above | 35 | 8.2% | |

| Mobile microblog experience | ≤3 years | 76 | 17.8% |

| >3 and ≤5 years | 194 | 63.1% | |

| >5 years | 158 | 36.9% |

| Variable | Item | Standard Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| External similarity (ES) | ES1 | 0.936 | 0.916 | 0.947 | 0.857 |

| ES2 | 0.922 | ||||

| ES3 | 0.918 | ||||

| Internal similarity (IS) | IS1 | 0.850 | 0.882 | 0.919 | 0.740 |

| IS2 | 0.911 | ||||

| IS3 | 0.873 | ||||

| IS4 | 0.806 | ||||

| Social interactive value (SIV) | SIV1 | 0.855 | 0.877 | 0.916 | 0.731 |

| SIV2 | 0.881 | ||||

| SIV3 | 0.880 | ||||

| SIV4 | 0.804 | ||||

| Visual appearance (VA) | VA1 | 0.905 | 0.884 | 0.928 | 0.811 |

| VA2 | 0.915 | ||||

| VA3 | 0.883 | ||||

| Identify attractiveness (IA) | IA1 | 0.898 | 0.856 | 0.912 | 0.777 |

| IA2 | 0.902 | ||||

| IA3 | 0.844 | ||||

| Cognitive involvement (CIN) | CIN1 | 0.894 | 0.875 | 0.923 | 0.800 |

| CIN2 | 0.914 | ||||

| CIN3 | 0.875 | ||||

| Affective involvement (AIN) | AIN1 | 0.904 | 0.880 | 0.926 | 0.806 |

| AIN2 | 0.908 | ||||

| AIN3 | 0.882 | ||||

| Mobile government microblog continuance (MGC) | MGC1 | 0.911 | 0.894 | 0.934 | 0.826 |

| MGC2 | 0.920 | ||||

| MGC3 | 0.895 |

| Mean | SD | AIN | CIN | ES | IA | IS | MGC | SIV | VA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIN | 5.122 | 1.578 | 0.898 | |||||||

| CIN | 5.084 | 1.523 | 0.5082 | 0.894 | ||||||

| ES | 4.759 | 1.623 | 0.2144 | 0.2834 | 0.926 | |||||

| IA | 5.185 | 1.437 | 0.3730 | 0.2813 | 0.1342 | 0.881 | ||||

| IS | 5.174 | 1.519 | 0.1544 | 0.2448 | 0.1337 | 0.2665 | 0.860 | |||

| MGC | 5.057 | 1.625 | 0.4594 | 0.4198 | 0.2792 | 0.3527 | 0.2164 | 0.909 | ||

| SIV | 5.217 | 1.488 | 0.2638 | 0.1543 | 0.0426 | 0.5364 | 0.1596 | 0.2207 | 0.855 | |

| VA | 5.354 | 1.483 | 0.2315 | 0.0925 | −0.0139 | 0.7934 | 0.0781 | 0.1832 | 0.6739 | 0.901 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ni, C.; Yang, S.; Pan, Y.; Yao, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y. Sustainability of Government Microblog in China: Exploring Social Factors on Mobile Government Microblog Continuance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6887. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su11246887

Ni C, Yang S, Pan Y, Yao J, Li Y, Chen Y. Sustainability of Government Microblog in China: Exploring Social Factors on Mobile Government Microblog Continuance. Sustainability. 2019; 11(24):6887. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su11246887

Chicago/Turabian StyleNi, Chenyuan, Shuiqing Yang, Yanqin Pan, Jianrong Yao, Yixiao Li, and Yuangao Chen. 2019. "Sustainability of Government Microblog in China: Exploring Social Factors on Mobile Government Microblog Continuance" Sustainability 11, no. 24: 6887. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su11246887