Key Elements for the Design of a Wine Route. The Case of La Axarquía in Málaga (Spain)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

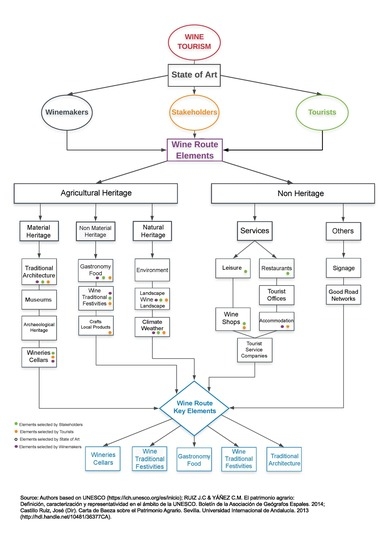

2. State of the Art

Elements Involved in the Design of Enotourist Itineraries

3. Materials and Methods

Territoriy under Study

4. Results

4.1. Elements According to the State of the Art

4.2. Elements Selected by Winemakers

4.3. Elements Selected by Stakeholders

4.4. Elements Selected by Wine Tourists

4.5. Key Elements Involved in the Wine Routes. Study Case

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Open Questionnaire Model. Axarquía Wine Route |

| Winemakers and Stakeholders |

| Name: |

| Position: |

| Institution/Company: |

| Date: |

| Ref#: |

|

| Tourists |

| Sex: |

| Age: |

| Country of origin: |

| City (Village) where you stay: |

| Length of stay (in days): |

| Type of accommodation: |

| Ref#: |

|

References

- Bessière, J. Manger ailleurs, manger “local”: La fonction touristique de la gastronomie de terroir. Espaces 2006, 242, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bessière, J.; Poulain, J.P.; y Tibère, L. Lálimentation au coeur du voyage. Le rôle du tourisme dans la valorisation des patrimoines alimentaires locaux. Tour. Rech. 2013, 3, 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Scheffer, S.; Pirou, J.L. La “gastronomie” dans la promotion d’une destination touristique: De l’image aux lieux de pratiques (analyse comparée de la Normandie et de la Bretagne). In Proceedings of the XLVIe Colloque ASRDLF, Entre Projets Locaux de Développement et Globalisation de L’économie: Quels Déséquilibres Pour les Espaces Régionaux, Clermont-Ferrand, France, 6–8 July 2009; Volume 6, p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, T.J.L.-G.; Cañizares, S.M.S. La creación de productos turísticos utilizando rutas enológicas. Pasos. Rev Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2008, 6, 159–171. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, F.X.; Tresserras Juan, J. Turismo enológico y rutas del vino en Cataluña: Análisis de casos: D.O. Penedès, D.O. Priorat y D.O. Montsant. Pasos. Rev Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2008, 6, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Armas, R.J. Potencialidad e integración del “turismo del vino” en un destino de sol y playa: El caso de Tenerife. Pasos. Rev Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2008, 6, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Alant, K. The hedonic nature of wine tourism consumption: An experiential view. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2009, 21, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Orden-Reyes, C.; Vargas-Sanchez, A. La satisfacción del turista enológico: Aplicación al condado de Huelva. In Proceedings of the Turismo y Sostenibilidad: V Jornadas de Investigación en Turismo, Sevilla, Spain, 17–18 May 2012; pp. 781–803. [Google Scholar]

- Tabasco, J.J.P.; Del Carmen Cañizares Ruiz, M.; Pulpón, Á.R.R. Patrimonio, viñedo y turismo: Recursos específicos para la innovación y el desarrollo territorial de Castilla-La Mancha. Cuad. Tur. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Romero de la Cruz, E.; De los Reyes Cruz Ruiz, E.; Zamarreño Aramendia, G. Rutas enológicas y desarrollo local. Presente y futuro en la provincia de Málaga. Int. J. Sci. Manag. Tour. 2017, 3, 283–310. [Google Scholar]

- ACEVIN. Asociación Española de Ciudades del Vino. 2020. Available online: https://www.acevin.es/ (accessed on 3 February 2020).

- Hosteltour. Web Hosteltour. 2019. Available online: https://www.hosteltur.com/ (accessed on 21 December 2019).

- Gilbert, D.C. Touristic Development of a Viticultural Region of Spain. Int. J. Wine Mark. 1992, 4, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.; Hall, C.M. Wine Tourism Research: The State of Play. Tour. Rev. Int. 2006, 9, 307–332. Available online: http://0-www-ingentaconnect-com.brum.beds.ac.uk/content/10.3727/154427206776330535 (accessed on 19 August 2020). [CrossRef]

- Marzo-Navarro, M.; Pedraja-Iglesias, M. Desarrollo del turismo del vino desde la perspectiva de los productores. Una primera aproximación al caso de Aragón—España. Estud. Perspect. Tur. 2012, 21, 585–603. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, A.D.; Liu, Y. Visitor Centers, Collaboration, and the Role of Local Food and Beverage as Regional Tourism Development Tools: The Case of the Blackwood River Valley in Western Australia. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Guzmán, T.; Garcia, J.R.; Rodriguez, Á.V. Revisión de la literatura cientifica sobre enoturismo en España. Cuad. Tur. 2013, 32, 171–188. [Google Scholar]

- López Guzmán, T.; Rodríguez García, J.; Vieira Rodríguez, A. Análisis diferenciado del perfil y de la motivación del turista nacional y extranjero en la ruta del vino del Marco de Jerez. Gran Tour 2012, 6, 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-García, J.; López-Guzmán, T.; Sánchez-Cañizares, S.M. Análisis del desarrollo del enoturismo en España–Un estudio de caso. Cult. Rev. Cult. Tur. 2010, 4, 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- López-Guzmán, T.; Cañizares, S.M.S.; García, R. Wine routes in Spain: A case study. Tourism 2009, 57, 421–434. [Google Scholar]

- López-Guzmán, T.; Millán Vázquez de la Torre, G.; Caridad y Ocerín, J.M. Análisis econométrico del enoturismo en España: Un estudio de caso. Estud. Perspect. Tur. 2008, 17, 98–118. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Gálvez, J.C. Motivation and tourist satisfaction in wine festivals: XXXI ed. wine tasting Montilla-Moriles, Spain. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alvear González, A.; Aparicio Castillo, S.; Landaluce Calvo, M.I. Una primera exploración de mercado enoturístico real de la ribera del duero. In Conocimiento, Innovación y Emprendedores: Camino al Futuro; Universidad de la Rioja: Logroño, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Rico, M. El Turismo Enológico Desde la Perspectiva de la Oferta; Editorial Universitaria Ramón Areces: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Clemente-Ricolfe, J.S.; Escribá-Pérez, C.; Rodriguez-Barrio, J.E.; Buitrago-Vera, J.M. The potential wine tourist market: The case of Valencia (Spain). J. Wine Res. 2012, 23, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez García, J.; Del Rio, M.D.L.C.; Coca Pérez, J.L.; González Sanmartín, J.M. Turismo enológico y ruta del vino del riberiro en Galicia-España. Estud. Perspect. Tur. 2014, 23, 706–729. [Google Scholar]

- Galacho Jiménez, F.; Luque Gil, A. La dinámica del paisaje de la costa del sol desde la aparición del turismo. Baética Estud. Arte Geogr. Hist. 2000, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberger, R.S.; Walsh, R.G. Nonmarket value of western valley ranchland using contingent valuation. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 1997, 22, 296–309. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Urrestarazu, E. Patrimonio Rural y Políticas Europeas. Lurralde Investig. Espac. 2001, 24, 305–314. [Google Scholar]

- Silva Pérez, R. Agricultura, paisaje y patrimonio territorial. Los paisajes de la agricultura vistos como patrimonio. Bol. Asoc. Geogr. Españoles 2009, 49, 309–334. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsen, J.; Boksberger, P. Enhancing Consumer Value in Wine Tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2015, 39, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CRDO Málaga. D.O. Málaga, Sierras de Málaga y Pasas de Málaga. Available online: www.vinomalaga.com (accessed on 19 August 2020).

- Alemeida García, F. La Costa del Sol Oriental como un Estudio de un Conflicto Territorial: La Planificación Ambiental Frente a la Urbanización; Servicio de Publicaciones e Intercambio Científico de la Universidad de Málaga: Málaga, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Elias Pastor, L.V. El Turismo del Vino. Otra Experiencia de Ocio; Universidad de Deusto: Bilbao, Spain, 2006; p. 256. Available online: http://www.deusto-publicaciones.es/deusto/pdfs/ocio/ocio30.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2020).

- Privitera, D. Heritage and wine as tourist attractions in rural areas. In Proceedings of the 116th EAAE Seminar, Parma, Italy, 27–30 October 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khartishvili, L.; Muhar, A.; Dax, T.; Khelashvili, I. Rural tourism in Georgia in transition: Challenges for regional sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cavicchi, A. Preserving the authenticity of food and wine festivals: The case of Italy. Cap. Cult. Stud. Value Cult. Herit. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolikow, S. Le vin de Champagne: De la visite à l’Oenotourisme, un chemin difficile. Cult. Rev. Cult. Tur. 2014, 8, 172–187. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, J.; Martin, A.; Nash, R. Overview of perceptions of German wine tourism from the winery perspective. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2013, 25, 50–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festa, G.; Shams, S.M.R.; Metallo, G.; Cuomo, M.T. Opportunities and challenges in the contribution of wine routes to wine tourism in Italy—A stakeholders’ perspective of development. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço-Gomes, L.; Pinto, L.M.C.; Rebelo, J. Wine and cultural heritage. the experience of the Alto Douro Wine Region. Wine Econ. Policy 2015, 4, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dougherty, P.H. The Geography of Wine: Regions, Terroir and Techniques; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2012; ISBN 9789400704640. [Google Scholar]

- Trišić, I.; Štetić, S.; Privitera, D.; Nedelcu, A. Wine routes in Vojvodina Province, Northern Serbia: A tool for sustainable tourism development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coros, M.M.; Pop, A.M.; Popa, A.I. Vineyards and wineries in Alba County, Romania towards sustainable business development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, F.M.; Singh, N. Determining the critical succes Factors of the wine Tourism Region of Napa from a supply perspective. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 13, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Brown, G. Benchmarking wine tourism development: The case of the Okanagan Valley, British Columbia, Canada. Int. J. Wine Mark. 2006, 18, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Wine tourism around the world: Development, management and markets. J. Wine Res. 2014, 25, 133–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojman, D.E.; Hunter-Jones, P. Wine tourism: Chilean wine regions and routes. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlüter, R.G.; Norrild, J. Enotourism in Argentina: The power of wine to promote a region. In Tourism in Latin America: Cases of Success; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.; Fesenmaier, D.R.; Fesenmaier, J.; Van Es, J.C. Factors for success in rural tourism development. J. Travel Res. 2001, 40, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilinsky, A.; Newton, S.K.; Atki, T.S.; Santini, C.; Cavicchi, A.; Casas, A.R.; Huertas, R. Perceived efficacy of sustainability strategies in the US, Italian, and Spanish wine industries a comparative study. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2015, 27, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montella, M.M. Wine tourism and sustainability: A review. Sustainability 2017, 9, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elías Pastor, L.V. Paisaje del viñedo: Patrimonio y recurso. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2008, 6, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, M.; White, L.; Frost, W. Wine and Identity: Branding, Heritage, Terroir; Taylor & Francis Group: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014; ISBN 9780203067604. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael, B.A. Understanding the wine tourism experience for winery visitors in the Niagara region, Ontario, Canada. Tour. Geogr. 2005, 7, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, R.S.; Fernández Salinas, V. El patrimonio y el territorio como activos para el desarrollo desde la perspectiva del ocio y el turismo. Investig. Geogr. 2008, 46, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mitchell, R.; Charters, S.; Albrecht, J.N. Cultural systems and the wine tourism product. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunori, G.; Rossi, A. Synergy and coherence through collective action: Some insights from wine routes in Tuscany. Sociol. Rural. 2000, 40, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macionis, N. Wine and Food Tourism in the Australian Capital Territory: Exploring the Links. Int. J. Wine Mark. 1998, 10, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telfer, D.J. Tastes of niagara: Building strategic alliances between tourism and agriculture. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2000, 1, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.D.; Liu, Y.; Duarte, A.; Liu, Y. International Journal of Hospitality Management The potential for marrying local gastronomy and wine: The case of the ‘fortunate islands’. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 974–981. Available online: https://0-www-sciencedirect-com.brum.beds.ac.uk/science/article/pii/S0278431911000326 (accessed on 20 January 2019). [CrossRef]

- Getz, D. Wine and Food Events: Experiences and Impacts. In Wine Tourism Destination Management and Marketing; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brochado, A.; Stoleriu, O.; Lupu, C. Wine tourism: A multisensory experience. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchi, B.; Gabbai, M. Territorial identity as a competitive advantage in wine marketing: A case study. J. Wine Res. 2013, 24, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristófol, F.J.; Aramendia, G.Z.; de-San-Eugenio-Vela, J. Effects of Social Media on Enotourism. Two Cases Study: Okanagan Valley (Canada) and Somontano (Spain). Sustainability 2020, 12, 6705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael Hall, C. Wine, Food, and Tourism Marketing; Taylor & Francis Group: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013; ISBN 9781315043395. [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto, A.; Telfer, D.J. Positioning an emerging wine route in the Niagara region: Understanding the wine tourism market and its implications for marketing. In Wine, Food, and Tourism Marketing; Taylor & Francis Group: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013; ISBN 9781315043395. [Google Scholar]

- De Uña-Álvarez, E.; Villarino-Pérez, M. Linking wine culture, identity, tourism and rural development in a denomination of origin territory (NW of Spain). Cuad. Tur. 2019, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lavandoski, J.; Pinto, P.; Silva, J.A.; Vargas-Sánchez, A. Causes and effects of wine tourism development in wineries: The perspective of institutional theory. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2016, 28, 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, H.; Holmes, M.; Jacobs, H.; Wade, R.I. Wine tourism: Winery visitation in the wine appellations of Ontario. J. Vacat. Mark. 2011, 17, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fazio, S.; Modica, G. Historic rural landscapes: Sustainable planning strategies and action criteria. The Italian experience in the Global and European Context. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buonincontri, P.; Marasco, A.; Ramkissoon, H. Visitors’ experience, place attachment and sustainable behaviour at cultural heritage sites: A conceptual framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hampton, M. Heritage, local communities and economic development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 735–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faugère, C.; Bouzdine-Chameeva, T.; Pesme, J.J.-O.; Durrieu, F. The Impact of Tourism Strategies and Regional Factors on Wine Tourism Performance: Bordeaux vs. Mendoza, Mainz, Florence, Porto and Cape Town. SSRN Electron. J. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Brown, G. Critical success factors for wine tourism regions: A demand analysis. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, D.; Byslma, B.; Ouschan, R. Customer perceived value in a cellar door visit: The impact on behavioural intentions. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2007, 19, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meraz Ruiz, L.; Ruiz Vega, A.V. El enoturismo de Baja California, México: Un análisis de su oferta y comparación con la región vitivinícola de La Rioja, España. Rev. Investig. Turísticas 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alonso, A.D.; Liu, Y. Coping with changes in a sector in crisis: The case of small Spanish wineries. J. Wine Res. 2012, 23, 81–95. Available online: http://0-www-tandfonline-com.brum.beds.ac.uk/doi/abs/10.1080/09571264.2011.646252 (accessed on 20 January 2019). [CrossRef]

- Popp, L.; McCole, D. Understanding tourists’ itineraries in emerging rural tourism regions: The application of paper-based itinerary mapping methodology to a wine tourism region in Michigan. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 988–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Carlsen, J.; Brown, G.; Havitz, M. Wine tourism and consumers. In Tourism Management: Analysis, Behaviour and Strategy; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2007; ISBN 9781845933234. [Google Scholar]

- Alant, K.; Bruwer, J. Wine tourism behaviour in the context of a motivational framework for wine regions and cellar doors. J. Wine Res. 2004, 15, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J. South African wine routes: Some perspectives on the wine tourism industry’s structural dimensions and wine tourism product. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famularo, B.; Bruwer, J.; Li, E. Region of origin as choice factor: Wine knowledge and wine tourism involvement influence. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2010, 22, 362–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Mitchell, R. Wine tourism in the Mediterranean: A tool for restructuring and development. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2000, 42, 445–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.P.; Havitz, M.E.; Getz, D. Relationship between wine involvement and wine-related travel. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2006, 21, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Bufquin, D.; Back, R.M. When do they become satiated? An examination of the relationships among winery tourists’ satisfaction, repat visit and revisit intentions. J. Dest Mark&Manag. 2019, 11, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.L.A.; Hunter, C.A. Wine tourism development in South Africa: A geographical analysis. Tour. Geogr. 2017, 19, 676–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo Ruiz, J.; Anguita Cantero, R.; Cañete Pérez, J.A.; Cejudo García, E.; Cuéllar Padilla, M.D.; Gallar Hernández, D.; Martínez Hidalgo, C.; Martínez Yáñez, C.; Matarán-Ruiz, A.; Ortega Ruiz, A.; et al. Carta de Baeza sobre Patrimonio Agrario.; Universidad Internacional de Andalucía: Sevilla, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cañizares Ruiz, M.C.; Ruiz Pulpón, A.R. Evolución del paisaje del viñedo en Castilla-La Mancha: Y revalorización del patrimonio afrario en el contexto de la modernización. Scripta Nova. 2014, 18. Available online: http://www.ub.edu/geocrit/sn/sn-498.htm (accessed on 8 July 2020).

- Jeambey, Z. Rutas Gastronómicas y Desarrollo local: Un ensayo de conceptualización en Cataluña. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2017, 14, 1187–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.; Quintal, V.A.; Phau, I. Predictors of attitude and intention to revisit a winescape. In Proceedings of the Australian and New Zealand Marketing Academy Conference, Christchurch, New Zealand, 29 November 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Molleví Bortoló, G.; Fusté Forné, F. El turismo gastronómico, rutas turísticas y productos locales: El caso del vino y el queso en Cataluña. Geographicalia 2017, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, Y.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Measuring Destination Attractiveness: A Contextual Approach. J. Travel Res. 1993, 32, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charters, S.; Menival, D. Wine tourism in champagne. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2011, 35, 102–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wargenau, A.; Che, D. Wine tourism development and marketing strategies in Southwest Michigan. Int. J. Wine Mark. 2006, 18, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Sharples, L.; Mitchell, R.; Macionis, N.; Cambourne, B. Food Tourism around the World; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsen, J. A review of global wine tourism research. J. Wine Res. 2004, 15, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.; Ben-Nun, L. The Important Dimensions of Wine Tourism Experience from Potential Visitors’ Perception. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2009, 9, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, M.P.; Navarro, M.M. Wine tourism development from the perspective of family winery [DEsarrollo del enoturismo desde la perspectiva de las bodegas familiares]. Cuad. Tur. 2014, 34, 233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsen, J.; Dowling, R. Wine Tourism Marketing Issues in Australia. Int. J. Wine Mark. 1998, 10, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, R.D.; Dominick, J.R. La Investigación Científica de los Medios de Comunicación. Una Introducción a Sus Métodos; Bosch: Barcelona, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Enquiry & Research Design, Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, J. Mixing methods in a qualitatively driven way. Qual. Res. 2006, 6, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepper, C.; Wildy, H. Using narratives as a research strategy. Qual. Res. J. 2009, 9, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis, A.; Jackson, W. Research Methods for Nurses: Methods and Interpretation; Davis Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon, W.; Madden, T.J.; Firtle, N.H. Marketing Research in a Marketing Environment; Richard, D., Ed.; Irwin. INC: Burr Ridge, IL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- AlYahmady, H.H.; Al Abri, S.S. Using Nvivo for Data Analysis in Qualitative Research. Int. Interdiscip. J. Educ. 2013, 2, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ponce de León Elizondo, A.; Valdemoros San Emeterio, M.A.; Sanz, E. Fundamentos en el manejo del NVIVO 9 como herramienta al servicio de estudios cualitativos. Context. Educ. Rev. Educ. 2011, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucena, D. Axarquía. Geografía Humana y Económica; CEDER Axarquía: Málaga, Spain, 2007; p. 88. ISBN 9788468951508. Available online: http://apta.axarquiacostadelsol.org/geografia-humana-y-economica-de-la-axarquia-pdf/ (accessed on 27 March 2020).

- IECA Estadísticas de Población. Available online: http://www.juntadeandalucia.es/institutodeestadisticaycartografia/temas/est/tema_poblacion.htm (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- Díaz Roldán, M.C. La Axarquía: Escenario de la crisis de la viticultura tradicional. Isla Arriarán Rev. Cult. Científica 1996, 8, 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Romero de la Cruz, E.; Zamarreño-Aramendia, G.; Cruz Ruiz, E. ¿ El Origen lo es Todo?: Ayer y Hoy de Las Denominaciones y Marcas Colectivas de Garantía en el Sector Vinícola en España; Ruíz Romero de la Cruz, E., Cruz Ruíz, E., Zamarreño Aramendia, G., Eds.; Universidad de Málaga: Málaga, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- CERVIM. 2020. Available online: http://www.cervim.org/es/cervim-presentaci-n.aspx (accessed on 6 May 2020).

| Tangible Heritage | Intangible Heritage | Natural Heritage | Services | Others | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors Elements | Historical/Traditional Architecture | Museums | Archaeological Heritage | Wineries Cellars | Gastronomy | Wine/Traditional Festivities | Crafts/Local Products | Environment | Landscape/Wine Landscape | Climate/Weather | Leisure | Wine Shops | Restaurants | Tourist Service Companies | Tourist Offices | Accommodation | Signage | Good Road Network |

| Alant and Bruwer (2009) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| Alonso and Liu (2011) | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| Baraja, Herrero, Martínez Arnáiz, Plaza (2019) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Baird, Hall and Castka (2019) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Bruwer (2003) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| Carlsen (2004) | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| Charters and Menival (2011) | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| Carmichael (2005) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Cohen and Ben-Nun (2009) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| De Uña-Álvarez and Villarino-Pérez (2019) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Faugère, et al. (2013) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Ferrerira and Hunter (2017) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Festa, Riad Shams, Metallo and Cuomo (2020) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Getz and Brown (2006) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Houghton (2008) | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| Jeambey (2016) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Kirova and Vo Thanh (2018) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Koch, Martin and Nash (2013) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Marzo and Pedraja (2012) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Meraz and Ruiz Vega (2016) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Mitchell and Hall (2006) | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| Movellí and Fuste (2016) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Plaza, Cañizares, Ruiz Pulpón (2017) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Popp and McCole (2016) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| Privitera (2010) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Scorrano, Fait, Iaia and Rosato (2018) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Thomas, Quintal and Phau (2010) | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| Ye, Hang and Yuan (2017) | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| Wargenau and Che (2006) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Data Collection Method | Open-Ended Structured Questionnaires |

|---|---|

| Sample: | Winemakers Institutions, Stakeholders linked to the Region of Axarquía Wine tourists |

| 80 | |

| April–November 2019 | |

| Sampling size | Wineries (10): Bodegas Hermanos López Martín, Bodega José Molina, Bodegas Almijara, Bodegas Luis Picante, Bodega A. Muñoz Cabrera, Bodegas Bentomiz, Sedella Vinos, Bodegas Medina y Toro, Bodegas Jorge Ordoñez & Co., Cooperativa Unión Pasera de La Axarquía (Ucopaxa) |

| Field Work Date | Stakeholders (10) (Member or representatives of these institutions): Association of Municipalities of the Axarquía, Center for Rural Development of the Axarquía (CEDER-Axarquía), Andalusian Regional Government Agriculture Delegation, Association for the Tourist Promotion of La Aaxarquía (APTA), Andalusian Tourism, Vélez Málaga Business Association, Nerja Business Association, Association of Young Farmers (ASAJA-Axaquia), Small Farmers Union (UPA-Axarquía) and Nerja Cave Foundation |

| 60 wine tourists |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cruz-Ruiz, E.; Zamarreño-Aramendia, G.; Ruiz-Romero de la Cruz, E. Key Elements for the Design of a Wine Route. The Case of La Axarquía in Málaga (Spain). Sustainability 2020, 12, 9242. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su12219242

Cruz-Ruiz E, Zamarreño-Aramendia G, Ruiz-Romero de la Cruz E. Key Elements for the Design of a Wine Route. The Case of La Axarquía in Málaga (Spain). Sustainability. 2020; 12(21):9242. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su12219242

Chicago/Turabian StyleCruz-Ruiz, Elena, Gorka Zamarreño-Aramendia, and Elena Ruiz-Romero de la Cruz. 2020. "Key Elements for the Design of a Wine Route. The Case of La Axarquía in Málaga (Spain)" Sustainability 12, no. 21: 9242. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su12219242