The Key Drivers of Born-Sustainable Businesses: Evidence from the Italian Fashion Industry

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Environmental Impact of Fashion Industry

2.2. The Drivers of a Sustainable Business

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample Selection

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

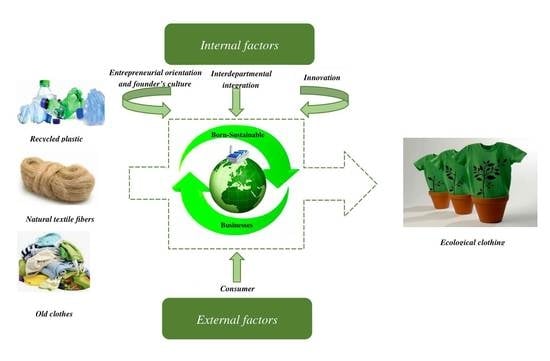

4.1. The Role of Internal Drivers for Born-Sustainable Businesses

4.1.1. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Founder’s Culture

4.1.2. Interdepartmental Integration

4.1.3. Innovation

4.2. The Role of External Drivers for Born-Sustainable Businesses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Z.; Jia, H.; Xu, T.; Xu, C. Manufacturing industrial structure and pollutant emission: An empirical study of China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukumarana, T.T.; Karunathilake, H.P.; Punchihewa, H.K.G.; Manthilake, M.M.I.D.; Hewage, K.N. Life cycle environmental impacts of the apparel industry in Sri Lanka: Analysis of the energy sources. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1346–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPRS. Environmental Impact of the Textile and Clothing Industry. What Consumers Need to Know; European Parliamentary Research Service: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gardas, B.B.; Raut, R.D.; Narkhede, B. Modelling the challenges to sustainability in the textile and apparel (T&A) sector: A Delphi-DEMATEL approach. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2018, 15, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mares, R. The limits of supply chain responsibility: A critical analysis of corporate responsibility instruments. Nord. J. Int. Law 2010, 79, 193–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Lai, K.H.; Geng, Y. The role of organizational size in the adoption of green supply chain management practices in China. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2008, 15, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdan, C.; Gazulla, C.; Raugei, M.; Martinez, E.; Fullana-i-Palmer, P. Proposal for new quantitative eco-design indicators: A first case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 1638–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Činčalová, S.; Hedija, V. Firm characteristics and corporate social responsibility: The case of Czech transportation and storage industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rasche, A.; Morsing, M.; Moon, J. Corporate Social Responsibility: Strategy, Communication, Governance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zimon, D.; Madzik, P.; Sroufe, R. The influence of ISO 9001 & ISO 14001 on sustainable supply chain management in the textile industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniato, F.; Caridi, M.; Crippa, L.; Moretto, A. Environmental sustainability in fashion supply chains: An exploratory case based research. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 135, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resta, B.; Gaiardelli, P.; Pinto, R.; Dotti, S. Enhancing environmental management in the textile sector: An Organisational-Life Cycle Assessment approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 620–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engert, S.; Rauter, R.; Baumgartner, R.J. Exploring the integration of corporate sustainability into strategic management: A literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 2833–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Accounting for the Triple Bottom Line. Meas. Bus. Excell. 1998, 2, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinna, L. Il Bilancio Sociale; Il Sole 24 Ore: Milano, Italy, 2002; ISBN 8883633962. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. AMR Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henninger, C.E. Traceability the new eco-label in the slow-fashion industry?—Consumer perceptions and micro-organisations responses. Sustainability 2015, 7, 6011–6032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salas-Molina, F.; Pla-Santamaria, D.; Vercher-Ferrándiz, M.L.; Reig-Mullor, J. Inverse Malthusianism and Recycling Economics: The Case of the Textile Industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, M.; Fauchart, E. Darwinians, Communitarians and Missionaries: The Role of Founder Identity in Entrepreneurship. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 935–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bansal, S.; Garg, I.; Sharma, G.D. Social entrepreneurship as a path for social change and driver of sustainable development: A systematic review and research agenda. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Christodoulides, P.; Kyrgidou, L.P. Internal Drivers and Performance Consequences of Small Firm Green Business Strategy: The Moderating Role of External Forces. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 585–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Menguc, B.; Auh, S.; Ozanne, L. The interactive effect of internal and external factors on a proactive environmental strategy and its influence on a firm’s performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 94, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todeschini, B.V.; Cortimiglia, M.N.; Callegaro-de-Menezes, D.; Ghezzi, A. Innovative and sustainable business models in the fashion industry: Entrepreneurial drivers, opportunities, and challenges. Bus. Horiz. 2017, 60, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulicelli, E. Fashion: The Cultural Economy of Made in Italy. Fash. Pract. 2014, 6, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.; Bender, J.; Lyons, T.; Borland, A. Natural and man-made selection for air pollution resistance. J. Exp. Bot. 1999, 50, 1423–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, V.; Feng, Y. Air pollution, greenhouse gases and climate change: Global and regional perspectives. Atmos. Environ. 2009, 43, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukumara, M.; Wheeler, D. In search of pollution havens? Dirty industry in the world economy, 1960 to 1995. In Proceedings of the OECD Conference on FDI and the Environment, The Hague, The Netherlands, 8–29 January 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta, S.; Mody, A.; Roy, S.; Wheeler, D.R. Environmental Regulation and Development: A Cross-Country Empirical Analysis; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sarwar, N.; Humayoun, U.B.; Khan, A.A.; Kumar, M.; Nawaz, A.; Yoo, J.H.; Yoon, D.H. Engineering of sustainable clothing with improved comfort and thermal properties—A step towards reducing chemical footprint. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 261, 121189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdil, A.; Taçgın, E. Potential risks and their analysis of the apparel & textile industry in Turkey: A quality-oriented sustainability approach. Fibres Text. East. Eur. 2018, 26, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kozlowski, A.; Bardecki, M.; Searcy, C. Environmental impacts in the fashion industry: A life cycle and stakeholder framework. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2012, 53, 1689–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C. Planned obsolescence and monopoly undersupply. Inf. Econ. Policy 2011, 23, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldini, I.; Stappers, P.J.; Gimeno-Martinez, J.C.; Daanen, H.A.M. Assessing the impact of design strategies on clothing lifetimes, usage and volumes: The case of product personalisation. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 1414–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, S. Eco–Chic: The Fashion Paradox; Black Dog Publishing: London, UK, 2008; ISBN 1906155097. [Google Scholar]

- Roos, S.; Zamani, B.; Sandin, G.; Peters, G.M.; Svanström, M. A life cycle assessment (LCA)-based approach to guiding an industry sector towards sustainability: The case of the Swedish apparel sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 133, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.C. Corporate social responsibility: Whether or how? Calif. Manag. Rev. 2003, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, P. Is the urban Indian consumer ready for clothing with eco-labels? Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2008, 32, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardetti, M.A.; Torres, A.L. Sustainability in Fashion and Textiles. Value, Design, Production and Consumption; Taylor & Francis, Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 9781906093785. [Google Scholar]

- Warasthe, M.; Brandenburg, R. Sourcing Organic Cotton from African Countries Potentials and Risks for the Apparel Industry Supply Chain. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hethorn, J.; Ulasewicz, C. Sustainable Fashion: Why Now? A Conversation Exploring Issues, Practices, and Possibilitie; Fairchild Books: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 156367534X. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, D.; Yang, J. Green supplier evaluation and selection in apparel manufacturing using a fuzzy multi-criteria decision-making approach. Sustainability 2017, 9, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.J. Reputation: Realizing Value from the Corporate Image; Harvard Business School Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 1995; ISBN 0875846335. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, P.; Rodríguez del Bosque, I. Sustainability Dimensions: A Source to Enhance Corporate Reputation. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2014, 17, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gunasekaran, A.; Irani, Z.; Papadopoulos, T. Modelling and analysis of sustainable operations management: Certain investigations for research and applications. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2014, 65, 806–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobby Banerjee, S. Corporate environmental strategies and actions. Manag. Decis. 2001, 39, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSimone, L.D.; Popoff, F. Eco-Efficiency: The Business Link to Sustainable Development; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Castka, P.; Balzarova, M.A.; Bamber, C.J.; Sharp, J.M. Implement the CSR Agenda? A UK Case Study Perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2004, 11, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, L.J.; Jeurissen, R.; Rutherfoord, R. Small Business and the Environment in the UK and the Netherlands. Bus. Ethics Q. 2000, 10, 945–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, M.; Taylor, N.; Barker, K. Environmental responsibility in SMEs: Does it deliver competitive advantage? Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2004, 13, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masurel, E. Why SMEs invest in environmental measures: Sustainability evidence from small and medium-sized printing firms. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2007, 16, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfat, C.E.; Peteraf, M. Managerial cognitive capabilities and the microfoundations of dynamic capabilities. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 36, 831–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Arago’n-Correa, J.A.; Rueda-Manzanares, A. The contingent influence of organizational capabilities on proactive environmental strategy in the service sector: An analysis of North American and European Ski Resorts. J. Adm. Sci. 2007, 24, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, T.; Hu, L.; Xiong, X.; Noman, M.T.; Mishra, R. Sound Absorption Properties of Natural Fibers: A Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Manag. Sci. 1983, 29, 770–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidomolu, R.; Prahalad, C.K.; Rangaswami, M.R. Why sustainability is now the key driver of innovation. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2009, 87, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revell, A.; Stokes, D.; Chen, H. Small business and the environment: Turning over a new leaf? Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2010, 19, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragón-Correa, J.A.; Martín-Tapia, I.; Hurtado-Torres, N.E. Proactive environmental strategies and employee inclusion: The positive effects of information sharing and promoting collaboration and the influence of uncertainty. Organ. Environ. 2013, 26, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Hodges, N. Corporate social responsibility in the apparel industry: An exploration of Indian consumers’ perceptions and expectations. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2012, 16, 216–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, K. Sustainable Fashion and Textiles: Design Journeys; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014; ISBN 0415644569. [Google Scholar]

- Niehm, L.S.; Swinney, J.; Miller, N.J. Community social responsibility and its consequences for family business performance. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2008, 46, 331–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B.; Bunderson, J.S.; Foreman, P.; Gustafson, L.T.; Huff, A.S.; Martins, L.L.; Reger, R.K.; Sarason, Y.; Stimpert, J.L. A strategy conversation on the topic of organization identity. In Identity in Organizations: Building Theory through Conversations; Whetten, A.D., Godfrey, P.C., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Whetten, D.; Mackey, A. A Social Actor Conception of Organizational Identity and Its Implications for the Study of Organizational Reputation. Bus. Soc. 2002, 41, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyakarnam, S.; Bailey, A.; Myers, A.; Burnett, D. Towards an understanding of ethical behaviour in small firms. J. Bus. Ethics 1997, 16, 1625–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, L.J.; Lozano, J.F. Communicating about Ethics with Small Firms: Experiences from the U.K. and Spain. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 27, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilley, F. Small firms’ environmental ethics: How deep do they go? Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2000, 9, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H. A Critique of Conventional CSR Theory: An SME Perspective. J. Gen. Manag. 2004, 29, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, C.; Delves, R.; Harris, P. Introduction Paper Ethical and Unethical Leadership: Double Vision? J. Public Aff. 2010, 10, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, S.J.; Scott, D. Compliance, Collaboration, and Codes of Labor Practice: The ADIDAS Connection. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2002, 45, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 9781452242569. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories from Case Study. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.K.; Corley, K.G. Building better theory by bridging the quantitative—Qualitative divide. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 1821–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Source Book; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Agency Theory: An Assessment and Review. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parris, D.L.; Peachey, J.W. A Systematic Literature Review of Servant Leadership Theory in Organizational Contexts. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 113, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oakes, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, J.; Simaens, A. Integrating sustainability into corporate strategy: A case study of the textile and clothing industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwepker, C.H.; Cornwell, T.B. An Examination of Ecologically Concerned Consumers and Their Intention to Purchase Ecologically Packaged Products. J. Public Policy Mark. 1991, 10, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Company | Company Information | Internal Factors | External Factors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Orientation and Founder’s Culture | Interdepartmental Integration | Innovation | Regulation | Consumer Awareness | Competitiveness | ||

| A | Production of regenerated clothing with cashmere and cotton. | × | × | × | - | × | - |

| B | Realization of overcoats from recycled plastic. | × | × | × | - | × | - |

| C | Realization of jeans from recycled textiles. | × | × | × | - | × | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dicuonzo, G.; Galeone, G.; Ranaldo, S.; Turco, M. The Key Drivers of Born-Sustainable Businesses: Evidence from the Italian Fashion Industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10237. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su122410237

Dicuonzo G, Galeone G, Ranaldo S, Turco M. The Key Drivers of Born-Sustainable Businesses: Evidence from the Italian Fashion Industry. Sustainability. 2020; 12(24):10237. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su122410237

Chicago/Turabian StyleDicuonzo, Grazia, Graziana Galeone, Simona Ranaldo, and Mario Turco. 2020. "The Key Drivers of Born-Sustainable Businesses: Evidence from the Italian Fashion Industry" Sustainability 12, no. 24: 10237. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su122410237