Could Smart Tourists Be Sustainable and Responsible as Well? The Contribution of Social Networking Sites to Improving Their Sustainable and Responsible Behavior

Abstract

:1. Introduction: Overtourism, Tourists’ Behavior and Smart Tourism Framework

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable and Responsible Tourist Behaviour

2.2. Smart Tourists

2.3. Social Media and Social Networking Sites and Their Impact on Tourist Consumer Behavior

2.3.1. SM and SNSs

2.3.2. The Impact of SM/SNSs on Tourist Behavior

3. Materials and Methods

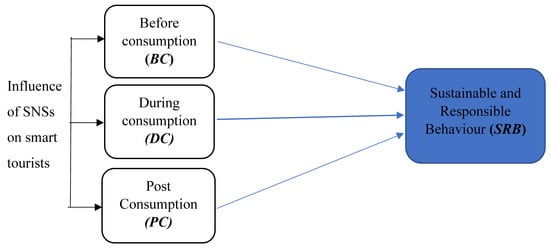

3.1. Suggested Framework for Sustainable and Responsible Behavior by Smart Tourists

- (1)

- Prior to the Trip—Responsible and Sustainable Preparation: Being smart and sustainable tourists is facilitated by serious preparation for the trip, mainly reading about and familiarizing themselves with the destination [2,20]. It is about self-education, studying the history of the area and getting to know the destination, as well as getting informed about the customs and practices of the visited country in order to enjoy the travel as much as possible and to avoid accidentally being disrespectful [63]. The getting-ready concept is congruent with the idea of being an intelligent tourist [64]. Tourists need to build an understanding of sites and locations to maximize personal enjoyment while anticipating that there will be a need for respecting local communities and resources [20,65];

- (2)

- Travelling and On-site—Sustainable and Responsible Travelers and Guests: Sustainable and responsible tourists and guests look for positive interaction and immersion [21,66]. Getting there, getting around and leaving the destinations are key phases of the tourists’ mobility efforts. The literature points out the value of using the existing smart systems to facilitate easy movement [14,67,68]. By facilitating a positive tourist experience, the responsible and smart tourists reduce their own frustration. This positive state of mind helps them have more cordial interactions with others. Applying this emotional self-monitoring represents a pathway to be civil to others and having good daily interactions [2]. They invest an effort to learn while they are on holidays/visit rather than just seeing the sights. They also immerse themselves in the new culture, looking for rewarding experiences, are considerate of their surroundings, behave as guests in their homeland and try to ensure a positive experience for themselves and for the local populations and lands [21,69]. The immediate savoring and the longer-term enjoyment is facilitated by the tourists immersing themselves in the activities of the site and maximizing their interactions with all those around them; this is the broad sense of co-creation [70]. The savoring and co-creation concepts can be linked to the benefits of slow and responsible tourism, an approach which stresses living more like a local, appreciating the local life and providing local economic benefits by behaving in a sustainable manner [2,71,72].

- (3)

- Post-Consumption—Back Home: When tourists are on their way back from the destination or have returned home, they usually take two actions: (i) evaluate the tourism experience against their expectations and (ii) share and exchange their tourism experience [9,35,73]. Tourists derive great enjoyment from this last stage of the travel cycle/tourist journey, but last in this case is not the least important. Based just upon the huge number of travel blogs and holiday photographs posted on SNSs, many consumers like to remember and share their tourism experiences [73,74]. With the advent of SNSs, it has become much more convenient for consumers to write about their pleasant and bad tourism experiences, particularly on virtual community platforms. A virtual tourism community makes it easier for individuals to obtain information, maintain connections, develop relationships and eventually make tourism-related decisions [36]. In addition to the review sites, virtual communities are gradually becoming incredibly influential in tourism, as consumers increasingly trust their peers better than marketing messages [9,35,55].

Research Framework and Hypotheses

3.2. Empirical Study: Research Design and Methodology

3.2.1. Instrument Development

3.2.2. Data Collection

4. Data Analysis: Results and Discussion

Reliability and Validity Testing

5. Conclusions, Implications and Future Research

5.1. Main Conclusions: Theoretical Contribution and Managerial Implications

5.2. Study’s Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNWTO. ‘Overtourism’?—Understanding and Managing Urban: Tourism Growth Beyond Perceptions; UN World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, P.L. Limiting overtourism; the desirable new behaviors of the smart tourist. In Proceedings of the T-Forum: The Tourism Intelligence Global Exchange Conference, Palma de Mallorca, Spain, 11–14 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Koens, K.; Postma, A.; Papp, B. Is over-tourism overused? Understanding the impact of tourism in a city context. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kruczek, Z. Tourists vs. Residents. The influence of excessive tourist attendance on the process of gentrification of historic cities; the example of raków. Turystyka Kulturowa 2018, 3, 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Benner, M. Overcoming overtourism in Europe: Towards an institutional-behavioral research agenda. Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsge-ographie 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, B.; Ye, Q.; Law, R. Effect of sharing economy on tourism industry employment. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 57, 264–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvan, E.; Dolnicar, S. The attitude–behaviour gap in sustainable tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 48, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, T.; Camargo, B.A. Sustainable tourism, justice and an ethic of care: Toward the Just Destination. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 22, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A.M. Marketing and Managing Tourism Destinations, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; Oxon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Juvan, E.; Dolnicar, S. Drivers of pro-environmental tourist behaviours are not universal. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 879–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Reino, S.; Kopera, S.; Koo, C. Smart tourism challenges. J. Tour. 2015, 6, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, J. Smart tourism. In Encyclopedia of Tourism; Jafari, J., Xiao, H., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY USA; Wien, Austria, 2016; pp. 862–863. [Google Scholar]

- Femenia-Serra, F.; Neuhofer, B. Smart tourism experiences: Conceptualisation, key dimensions and research agenda. J. Reg. Res. 2018, 42, 129–150. [Google Scholar]

- Gretzel, U.; Zhong, L.; Koo, C. Application of smart tourism to cities. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2016, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Sigala, M.; Xiang, Z.; Koo, C. Smart tourism: Foundations and developments. Electron. Mark. 2015, 25, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Femenia-Serra, F.; Perles-Ribes, J.; Ivars-Baidal, J. Smart destinations and tech-savvy millennial tourists: Hype versus reality. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Femenia-Serra, F.; Neuhofer, B.; Ivars-Baidal, J.A. Towards a conceptualization of smart tourists and their role within the smart destination scenario. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 39, 109–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Munar, A.M. Social media. In Encyclopedia of Tourism; Jafari, J., Xiao, H., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA; Wien, Austria, 2016; pp. 869–871. [Google Scholar]

- Sigala, M.; Christou, E.; Gretzel, U. (Eds.) Social Media in Travel, Tourism and Hospitality: Theory, Practice and Cases; Ashgate: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Passafaro, P. Attitudes and tourists’ sustainable behavior: An overview of the literature and discussion of some theoretical and methodological issues. J. Travel Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffa, F. Young tourists and sustainability: Profiles, attitudes, and implications for destination strategies. Sustainability 2015, 7, 14042–14062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dolnicar, S.; Long, P. Beyond ecotourism: The environmentally responsible tourist in the general travel experience. Tour. Anal. 2009, 14, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walker, K.; Moscardo, G. Encouraging sustainability beyond the tourist experience. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 1175–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvan, E.; Dolnicar, S. Measuring environmentally sustainable tourist behaviour. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 59, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S. Insights into sustainable tourists in Austria: A data-based a priori segmentation approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2004, 12, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.H.; Yang, C.C. Conceptualizing and measuring environmentally responsible behaviors from the perspective of community-based tourists. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 454–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, H.Y.-T.; Lee, W.-I.; Chen, T.-H. Environmentally responsible behaviour in ecotourism: Antecedents and implications. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Matus, K. Are green tourists a managerially useful target segment? J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2008, 1, 314–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, H.; Francis, J. Ethical and responsible tourism. J. Vacat. Mark. 2003, 9, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmetoglu, M. Factors influencing the willingness to behave environmentally friendly at home and holiday settings. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2010, 10, 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Merrilees, B.; Coghlan, A. Sustainable urban tourism: Understanding and developing visitor pro-environmental behaviours. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 23, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Tips for a Responsible Traveler: Travel, Enjoy, Respect; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dolnicar, S. Identifying tourists with smaller environmental footprints. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 717–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, W.G.; Lim, H.; Brymer, R.A. The effectiveness of managing social media on hotel performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 44, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ETC/UNWTO. Handbook on E-Marketing for Tourism Destinations; UNWTO: Brussels, Belgium; Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Bowen, J.T.; Makens, J.C. Marketing for Hospitality and Tourism, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gajdosik, T. Smart tourists as a profiling market segment: Implications for DMOs. Tour. Econ. 2019, (in press). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benckendorff, P.; Sheldon, P.J.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Tourism Information Technology, 2nd ed.; CABI: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Choe, Y.; Fesenmaier, D.R. The quantified traveller: Implications for smart tourism development. In Analytics in Smart Tourism Design, Tourism on the Verge; Xiang, Z., Fesenmaier, D.R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Park, S.; Fesenmaier, D.R. The role of smartphones in mediating the touristic experience. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buhalis, D.; Foerste, M. SoCoMo marketing for travel and tourism: Empowering co-creation of value. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiriadis, M. Sharing tourism experiences in social media: A literature review and a set of suggested business strategies. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 179–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Magnini, V.P.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Information technology and consumer behavior in travel and tourism: Insights from travel planning using the internet. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 22, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.M.; Woo, M.; Nam, K.; Chathoth, K.P. Smart city and smart tourism: A case of Dubai. Sustainability 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neuhofer, B. An exploration of the technology enhanced tourist experience. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 12, 220–223. [Google Scholar]

- Gretzel, U.; Yoo, K.-H. Premises and promises of social media marketing in tourism. In The Routledge Handbook of Tourism Marketing; McCabe, S., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 491–504. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, Q.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Defining the virtual tourist community: Implications for tourism marketing. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kietzmann, J.H.; Hermkens, K.; McCarthy, I.P.; Silvestre, B.S. Social media? Get serious! Understanding the functional building blocks of social media. Bus. Horiz. 2011, 54, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Available online: https://0-www-statista-com.brum.beds.ac.uk/statistics/278414/number-of-worldwide-social-network-users/ (accessed on 12 September 2019).

- Statista. Available online: https://0-www-statista-com.brum.beds.ac.uk/topics/1164/social-networks/ (accessed on 12 September 2019).

- Chung, N.; Tyan, I.; Chung, H.C. Social support and commitment within social networking site in tourism experience. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Law, R.; Buhalis, D.; Cobanoglu, C. Progress on information and communication technologies in hospitality and tourism. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 727–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvass, K.A.; Munar, A.M. The take-off of social media in tourism. J. Vacat. Mark. 2012, 18, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sotiriadis, M. The potential contribution and uses of Twitter by tourism businesses and destinations. Int. J. Online Mark. 2016, 6, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotis, J.N. The Use of Social Media and Its Impacts on Consumer Behaviour: The Context of Holiday Travel. Ph.D. Thesis, Bournemouth University, Bournemouth, UK, May 2015. Available online: http://eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/22506/1/JOHN%20FOTIS%20-%20PhD.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2019).

- Brandt, T.; Bendler, J.; Neumann, D. Social media analytics and value creation in urban smart tourism ecosystems. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Schuett, M.A. Determinants of sharing travel experiences in social media. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Tussyadiah, I.P. Social networking and social support in tourism experience: The moderating role of online self-presentation strategies. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munar, A.M.; Jacobsen, J.K.S. Motivations for sharing tourism experiences through social media. Tour. Manag. 2014, 43, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.D.; Goo, J.; Nam, K.; Yoo, C.W. Smart tourism technologies in travel planning: The role of exploration and exploitation. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 757–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.-T.B.; Gebsombut, N. Communication factors affecting tourist adoption of social network sites. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Orams, M.B. The effectiveness of environmental education: Can we turn tourists into ‘greenies’? Prog. Tour. Hosp. Res. 1997, 3, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, P.L. Understanding and fostering intelligent tourist behaviour. Tour. Trib. 2015, 30, 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kiatkawsin, K.; Han, H. Young travelers’ intention to behave pro-environmentally: Merging the value-belief-norm theory and the expectancy theory. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Fostering customers’ pro-environmental behavior at a museum. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1240–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Werthner, H.; Koo, C.; Lamsfus, C. Conceptual foundations for understanding smart tourism ecosystems. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 50, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Big data analytics, tourism design and smart Tourism. In Analytics in Smart Tourism Design; Xiang, Z., Fesenmaier, D.R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 299–307. [Google Scholar]

- Dolnicar, S.; Crouch, G.I.; Long, P. Environment-friendly tourists: What do we really know about them? J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prebensen, N.K.; Vittersø, J.; Dahl, T.I. Value co-creation significance of tourist resources. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 42, 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullagar, S.; Markwell, K.; Wilson, E. (Eds.) Slow Tourism: Experiences and Mobilities; Channel View: Bristol, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, B.; Choi, K. The role of authenticity in forming slow tourists’ intentions: Developing an extended model of goal-directed behavior. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-C.; Liu, C.-H. Moderating and mediating roles of environmental concern and ecotourism experience for revisit intention. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 1854–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Zschiegner, A.-K.; Xi, J.; Barkmann, J.; Marggraf, R. Is the Chinese tourist ready for sustainable tourism? Attitudes and preferences for sustainable tourism services. Int. J. Chin. Cult. Manag. 2010, 3, 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dichter, A.; Chen, G.; Saxon, S.; Yu, J.; Suo, P. Chinese Tourists: Dispelling the Myths: An In-Depth Look at China’s Outbound Tourist Market; McKinsey: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Available online: www.mckinseychina.com (accessed on 12 September 2019).

- Wang, D.; Li, X.R.; Li, Y. China’s “smart tourism destination” initiative: A taste of the service-dominant logic. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2013, 2, 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somekh, B.; Lewin, C. (Eds.) Research Methods in the Social Sciences; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

| Field/Area | Tips for Appropriate Behavior |

|---|---|

| Honor the Hosts and the Common heritage |

|

| Protect the Planet |

|

| Support the Local economy |

|

| Be an Informed Tourist |

|

| Be a Respectful Tourist |

|

| Stage of Travel Cycle | Consumer Behavior in Terms of Actions | Sustainable and Responsible Tourists: Set of Anticipatory Activities and Actual Behaviors |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-consumption | Searching and planning Expectations Buying (shopping and booking) Anticipation Preparation | Building an understanding, self-educating, getting ready:

|

| Consumption (on-site) | Experiencing Enjoying Searching Short-term decisions On-site purchase On-site evaluation | Travelling, visiting and enjoying:

|

| Post-consumption (back home) | Evaluation, remembering and sharing their experiences, mainly posting reviews and recommendations on social networking sites (SNSs) | Recollecting, sharing and recommending:

|

| Characteristics | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male Female | 179 325 | 35.5 64.5 |

| Age group | ||

| 18 to 25 26 to 30 31 to 35 36 to 45 46 to 55 56 to 65 65+ | 339 104 27 21 13 0 0 | 67.3 20.5 5.4 4.2 2.6 0 0 |

| Educational level | ||

| High school Undergraduate student Postgraduate student Other | 21 347 115 21 | 4.1 68.9 22.9 4.1 |

| Occupation | ||

| Student Admin/Office employee Artisan/Technician Services Civil servant Businessman Other | 262 96 36 37 21 23 29 | 52.0 19.1 7.1 7.2 4.2 4.6 5.8 |

| Tourism experiences (in numbers) | ||

| 1 to 3 4 to 6 7 to 10 11 to 20 21+ | 97 172 131 76 28 | 19.3 34.1 26.0 15.1 5.5 |

| Using SNSs for: | ||

| 1 to 11 months 1 year 2 years 3 years Longer than 3 years | 132 76 66 48 182 | 26.2 15.1 13.1 9.5 36.1 |

| Construct | Items | Mean | Standard Deviation | Standard Loading | t-Test | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before-consumption | 1.1 Understand | 3.45 | 0.944 | 0.819 | −1.684 | 0.8334 | 0.6253 | 0.828 |

| 1.2 Self-educate | 3.64 | 0.948 | 0.795 | −6.218 | ||||

| 1.3 Get ready | 4.06 | 0.843 | 0.757 | 9.257 | ||||

| During-consumption | 2.1 Learn | 3.67 | 0.944 | 0.804 | −1.269 | 0.8928 | 0.6253 | 0.892 |

| 2.2 Immerse | 3.58 | 0.961 | 0.819 | −3.193 | ||||

| 2.3 Rewarding experience | 3.93 | 0.851 | 0.725 | 5.450 | ||||

| 2.4 Mutually beneficial experience | 3.78 | 0.912 | 0.784 | 1.521 | ||||

| 2.5 Behave properly as guests | 3.66 | 0.921 | 0.818 | −1.397 | ||||

| Post-consumption | 3.1 Evaluate/share experience | 3.84 | 0.806 | 0.735 | 5.218 | 0.8672 | 0.5667 | 0.876 |

| 3.2 Influence other consumers | 3.69 | 0.820 | 0.746 | −2.195 | ||||

| 3.3 Participate in viral communities | 3.56 | 0.905 | 0.788 | −4.050 | ||||

| 3.4 Make suggestions | 3.70 | 0.971 | 0.723 | 1.054 | ||||

| 3.5 Advocate | 3.48 | 0.941 | 0.770 | 1.073 | ||||

| Sustainable and responsible behavior | 4.1 Before-consumption | 4.04 | 0.781 | 0.740 | 4.128 | 0.8176 | 0.6001 | 0.806 |

| 4.2 During-consumption | 3.90 | 0.656 | 0.844 | −0.109 | ||||

| 4.3 Post-consumption | 3.78 | 0.733 | 0.735 | −3.624 |

| Constructs | BC | DC | PC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | ||||

| 1.1 Understand | 0.777 | |||

| 1.2 Self-educate | 0.759 | |||

| 1.3 Get ready | 0.675 | |||

| 2.1 Learn | 0.784 | |||

| 2.2 Immerse | 0.813 | |||

| 2.3 Rewarding experience | 0.620 | |||

| 2.4 Mutually beneficial experience | 0.771 | |||

| 2.5 Behave properly as guests | 0.778 | |||

| 3.1 Evaluate/share experience | 0.642 | |||

| 3.2 Influence others | 0.719 | |||

| 3.3 Participate in viral communities | 0.823 | |||

| 3.4 Make suggestions | 0.654 | |||

| 3.5 Advocate | 0.780 | |||

| BC | DC | PC | RSB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1: BC | 1 | 0.856 ** | 0.813 ** | 0.594 ** |

| X2: DC | 0.856 ** | 1 | 0.871 ** | 0.619 ** |

| X3: PC | 0.813 ** | 0.871 ** | 1 | 0.609 ** |

| Y: SRB | 0.594 ** | 0.619 ** | 0.609 ** | 1 |

| R * | R2 * | ∆R2 * | Std. Error of the Estimate | Durbin–Watson | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 0.720 a | 0.519 | 0.516 | 0.626 | 1.552 |

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standard Regression Coefficient | t | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SEB (Standard Error of B) | β | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 0.162 | 0.147 | 1.105 | 0.270 | |

| BC | 0.369 | 0.071 | 0.323 | 5.191 | 0.000 | |

| DC | 0.334 | 0.087 | 0.285 | 3.855 | 0.000 | |

| PC | 0.185 | 0.081 | 0.150 | 2.291 | 0.022 | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shen, S.; Sotiriadis, M.; Zhou, Q. Could Smart Tourists Be Sustainable and Responsible as Well? The Contribution of Social Networking Sites to Improving Their Sustainable and Responsible Behavior. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1470. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su12041470

Shen S, Sotiriadis M, Zhou Q. Could Smart Tourists Be Sustainable and Responsible as Well? The Contribution of Social Networking Sites to Improving Their Sustainable and Responsible Behavior. Sustainability. 2020; 12(4):1470. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su12041470

Chicago/Turabian StyleShen, Shiwei, Marios Sotiriadis, and Qing Zhou. 2020. "Could Smart Tourists Be Sustainable and Responsible as Well? The Contribution of Social Networking Sites to Improving Their Sustainable and Responsible Behavior" Sustainability 12, no. 4: 1470. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su12041470