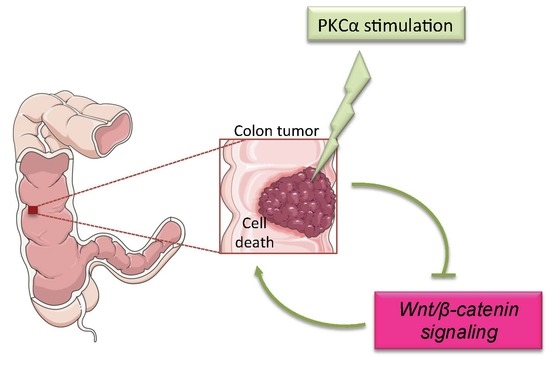

Modulating PKCα Activity to Target Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling in Colon Cancer

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Infrequent Inactivating Mutations of PKCα in Human Intestinal Tumors

2.2. Increasing PKCα Activity in the Healthy Intestinal Epithelium Is Not Deleterious

2.3. Increasing PKCα Activity in DLD-1 CRC Cells Disrupts Cell Morphology and Causes Cell Cycle Arrest

2.4. Increasing PKCα Activity in DLD-1 CRC Cells Prevents Cell Growth and Promotes Cell Death

2.5. Di-Terpene Esters Inhibit CRC Cell Growth with Different Potencies

3. Discussion

3.1. PKCα Integrity Is Preserved in Most Human CRCs

3.2. Inducing PKCα Function Is Not Deleterious for the Normal Intestinal Epithelium

3.3. Inducing PKCα Activity Potently Inhibits the Growth and Triggers the Death of CRC Cells

3.4. PKCα Activity Is Drug-Targetable

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Culture of Colon Cancer Cells and Generation of the DLD-1-PKCα Cell Line

4.2. Characterization of the PKCα-Induced Colon Cancer Cells Growth Arrest

4.3. Antibodies and Dyes

4.4. Generation of the R26-PKCαTg/Tg and Villin-Cre;R26-PKCαTg/Tg Mice

4.5. Characterization of the Mouse Phenotypes

4.6. Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining, Immunohistochemistry

4.7. Western Blotting

4.8. Statistics

4.9. Ethics Approval

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Klaus, A.; Birchmeier, W. Wnt signalling and its impact on development and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, B.T.; Tamai, K.; He, X. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: Components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev. Cell 2009, 17, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gammons, M.V.; Renko, M.; Johnson, C.M.; Rutherford, T.J.; Bienz, M. Wnt Signalosome Assembly by DEP Domain Swapping of Dishevelled. Mol. Cell 2016, 64, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paclikova, P.; Bernatik, O.; Radaszkiewicz, T.W.; Bryja, V. N-terminal part of Dishevelled DEP domain is required for Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shay, J.W. Multiple Roles of APC and its Therapeutic Implications in Colorectal Cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2017, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sansom, O.J.; Meniel, V.S.; Muncan, V.; Phesse, T.J.; Wilkins, J.A.; Reed, K.R.; Vass, J.K.; Athineos, D.; Clevers, H.; Clarke, A.R. Myc deletion rescues Apc deficiency in the small intestine. Nature 2007, 446, 676–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nakamura, S.; Yamamura, H. Yasutomi Nishizuka: Father of protein kinase C. J. Biochem. 2010, 148, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Castagna, M.; Takai, Y.; Kaibuchi, K.; Sano, K.; Kikkawa, U.; Nishizuka, Y. Direct activation of calcium-activated, phospholipid-dependent protein kinase by tumor-promoting phorbol esters. J. Biol. Chem. 1982, 257, 7847–7851. [Google Scholar]

- Antal, C.E.; Hudson, A.M.; Kang, E.; Zanca, C.; Wirth, C.; Stephenson, N.L.; Trotter, E.W.; Gallegos, L.L.; Miller, C.J.; Furnari, F.B.; et al. Cancer-associated protein kinase C mutations reveal kinase’s role as tumor suppressor. Cell 2015, 160, 489–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, I.K.; Ritland, S.R.; Burgart, L.J.; Ziesmer, S.C.; Roche, P.C.; Gendler, S.J.; Karnes, W.E., Jr. Adenoma-specific alterations of protein kinase C isozyme expression in Apc(MIN) mice. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 2077–2080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oster, H.; Leitges, M. Protein kinase C alpha but not PKCzeta suppresses intestinal tumor formation in ApcMin/+ mice. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 6955–6963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaglione-Sewell, B.; Abraham, C.; Bissonnette, M.; Skarosi, S.F.; Hart, J.; Davidson, N.O.; Wali, R.K.; Davis, B.H.; Sitrin, M.; Brasitus, T.A. Decreased PKC-alpha expression increases cellular proliferation, decreases differentiation, and enhances the transformed phenotype of CaCo-2 cells. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 1074–1081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Batlle, E.; Verdu, J.; Dominguez, D.; del Mont Llosas, M.; Diaz, V.; Loukili, N.; Paciucci, R.; Alameda, F.; de Herreros, A.G. Protein kinase C-alpha activity inversely modulates invasion and growth of intestinal cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 15091–15098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxon, M.L.; Zhao, X.; Black, J.D. Activation of protein kinase C isozymes is associated with post-mitotic events in intestinal epithelial cells in situ. J. Cell Biol. 1994, 126, 747–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frey, M.R.; Saxon, M.L.; Zhao, X.; Rollins, A.; Evans, S.S.; Black, J.D. Protein kinase C isozyme-mediated cell cycle arrest involves induction of p21(waf1/cip1) and p27(kip1) and hypophosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein in intestinal epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 9424–9435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupasquier, S.; Abdel-Samad, R.; Glazer, R.I.; Bastide, P.; Jay, P.; Joubert, D.; Cavailles, V.; Blache, P.; Quittau-Prevostel, C. A new mechanism of SOX9 action to regulate PKCalpha expression in the intestine epithelium. J. Cell Sci. 2009, 122 Pt 13, 2191–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assert, R.; Kotter, R.; Bisping, G.; Scheppach, W.; Stahlnecker, E.; Muller, K.M.; Dusel, G.; Schatz, H.; Pfeiffer, A. Anti-proliferative activity of protein kinase C in apical compartments of human colonic crypts: Evidence for a less activated protein kinase C in small adenomas. Int. J. Cancer 1999, 80, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.M.; Kim, I.S.; Kim, H.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, K.; Yim, H.Y.; Jeong, J.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, H.; et al. RORalpha attenuates Wnt/beta-catenin signaling by PKCalpha-dependent phosphorylation in colon cancer. Mol. Cell 2010, 37, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwak, J.; Cho, M.; Gong, S.J.; Won, J.; Kim, D.E.; Kim, E.Y.; Lee, S.S.; Kim, M.; Kim, T.K.; Shin, J.G.; et al. Protein-kinase-C-mediated beta-catenin phosphorylation negatively regulates the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. J. Cell Sci. 2006, 119 Pt 22, 4702–4709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, C.; Scaglione-Sewell, B.; Skarosi, S.F.; Qin, W.; Bissonnette, M.; Brasitus, T.A. Protein kinase C alpha modulates growth and differentiation in Caco-2 cells. Gastroenterology 1998, 114, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.C.; Rangachari, P.K.; Matthews, J.B. Opposing effects of PKCalpha and PKCepsilon on basolateral membrane dynamics in intestinal epithelia. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2002, 283, C1548–C1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyabi, O.; Naessens, M.; Haigh, K.; Gembarska, A.; Goossens, S.; Maetens, M.; De Clercq, S.; Drogat, B.; Haenebalcke, L.; Bartunkova, S.; et al. Efficient mouse transgenesis using Gateway-compatible ROSA26 locus targeting vectors and F1 hybrid ES cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Marjou, F.; Janssen, K.P.; Chang, B.H.; Li, M.; Hindie, V.; Chan, L.; Louvard, D.; Chambon, P.; Metzger, D.; Robine, S. Tissue-specific and inducible Cre-mediated recombination in the gut epithelium. Genesis 2004, 39, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hizli, A.A.; Black, A.R.; Pysz, M.A.; Black, J.D. Protein kinase C alpha signaling inhibits cyclin D1 translation in intestinal epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 14596–14603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, L.; Song, K.; Pysz, M.A.; Curry, K.J.; Hizli, A.A.; Danielpour, D.; Black, A.R.; Black, J.D. Protein kinase C-mediated down-regulation of cyclin D1 involves activation of the translational repressor 4E-BP1 via a phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt-independent, protein phosphatase 2A-dependent mechanism in intestinal epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 14213–14225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pysz, M.A.; Leontieva, O.V.; Bateman, N.W.; Uronis, J.M.; Curry, K.J.; Threadgill, D.W.; Janssen, K.P.; Robine, S.; Velcich, A.; Augenlicht, L.H.; et al. PKCalpha tumor suppression in the intestine is associated with transcriptional and translational inhibition of cyclin D1. Exp. Cell Res. 2009, 315, 1415–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pysz, M.A.; Hao, F.; Hizli, A.A.; Lum, M.A.; Swetzig, W.M.; Black, A.R.; Black, J.D. Differential regulation of cyclin D1 expression by protein kinase C alpha and signaling in intestinal epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 22268–22283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staal, F.J.; van Noort, M.; Strous, G.J.; Clevers, H.C. Wnt signals are transmitted through N-terminally dephosphorylated beta-catenin. EMBO Rep. 2002, 3, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetsu, O.; McCormick, F. Beta-catenin regulates expression of cyclin D1 in colon carcinoma cells. Nature 1999, 398, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahl-Rainer, P.; Karner-Hanusch, J.; Weiss, W.; Marian, B. Five of six protein kinase C isoenzymes present in normal mucosa show reduced protein levels during tumor development in the human colon. Carcinogenesis 1994, 15, 779–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serova, M.; Ghoul, A.; Benhadji, K.A.; Faivre, S.; Le Tourneau, C.; Cvitkovic, E.; Lokiec, F.; Lord, J.; Ogbourne, S.M.; Calvo, F.; et al. Effects of protein kinase C modulation by PEP005, a novel ingenol angleate, on mitogen-activated protein kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling in cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008, 7, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, S.A.; Cozzi, S.J.; Pierce, C.J.; Pavey, S.J.; Parsons, P.G.; Boyle, G.M. The induction of senescence-like growth arrest by protein kinase C-activating diterpene esters in solid tumor cells. Investig. New Drugs 2010, 28, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prevostel, C.; Alvaro, V.; Vallentin, A.; Martin, A.; Jaken, S.; Joubert, D. Selective loss of substrate recognition induced by the tumour-associated D294G point mutation in protein kinase Calpha. Biochem. J. 1998, 334 Pt 2, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, T.; Rindtorff, N.; Boutros, M. Wnt signaling in cancer. Oncogene 2017, 36, 1461–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Theodoropoulos, P.C.; Eskiocak, U.; Wang, W.; Moon, Y.A.; Posner, B.; Williams, N.S.; Wright, W.E.; Kim, S.B.; Nijhawan, D.; et al. Selective targeting of mutant adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) in colorectal cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 361ra140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, S.; Simeonova, I.; Bielle, F.; Verreault, M.; Bance, B.; Le Roux, I.; Daniau, M.; Nadaradjane, A.; Gleize, V.; Paris, S.; et al. A recurrent point mutation in PRKCA is a hallmark of chordoid gliomas. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Q.; Smart, R.C. Overexpression of protein kinase C-alpha in the epidermis of transgenic mice results in striking alterations in phorbol ester-induced inflammation and COX-2, MIP-2 and TNF-alpha expression but not tumor promotion. J. Cell Sci. 1999, 112 Pt 20, 3497–3506. [Google Scholar]

- Prevostel, C.; Alvaro, V.; de Boisvilliers, F.; Martin, A.; Jaffiol, C.; Joubert, D. The natural protein kinase C alpha mutant is present in human thyroid neoplasms. Oncogene 1995, 11, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Frey, M.R.; Clark, J.A.; Leontieva, O.; Uronis, J.M.; Black, A.R.; Black, J.D. Protein kinase C signaling mediates a program of cell cycle withdrawal in the intestinal epithelium. J. Cell Biol. 2000, 151, 763–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, A.R.; Black, J.D. Protein kinase C signaling and cell cycle regulation. Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newton, A.C.; Brognard, J. Reversing the Paradigm: Protein Kinase C as a Tumor Suppressor. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 38, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mochly Rosen, D.; Das, K.; Grimes, K.V. Protein kinase C, an elusive therapeutic target? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012, 11, 937–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perletti, G.P.; Folini, M.; Lin, H.C.; Mischak, H.; Piccinini, F.; Tashjian, A.H., Jr. Overexpression of protein kinase C epsilon is oncogenic in rat colonic epithelial cells. Oncogene 1996, 12, 847–854. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z.T.; Zhu, X.X.; Yang, R.Y.; Sun, J.Z.; Tian, G.F.; Liu, X.J.; Cao, G.S.; Newmark, H.L.; Conney, A.H.; Chang, R.L. Effect of intravenous infusions of 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) in patients with myelocytic leukemia: Preliminary studies on therapeutic efficacy and toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 5357–5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Strair, R.K.; Schaar, D.; Goodell, L.; Aisner, J.; Chin, K.V.; Eid, J.; Senzon, R.; Cui, X.X.; Han, Z.T.; Knox, B.; et al. Administration of a phorbol ester to patients with hematological malignancies: Preliminary results from a phase I clinical trial of 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2002, 8, 2512–2518. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, B.; Song, Y.; Han, Z.; Wei, X.; Lin, Q.; Zhu, X.; Yang, R.; Sun, J.; Tian, G.; Liu, X.; et al. Synergistic interactions between 12-0-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) and imatinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in blastic phase that is resistant to standard-dose imatinib. Leuk. Res. 2007, 31, 1441–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furstenberger, G.; Berry, D.L.; Sorg, B.; Marks, F. Skin tumor promotion by phorbol esters is a two-stage process. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1981, 78, 7722–7726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, A.C.; Beardmore, G.L. Home treatment of skin cancer and solar keratoses. Australas. J. Dermatol. 1988, 29, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zayed, S.M.; Farghaly, M.; Taha, H.; Gotta, H.; Hecker, E. Dietary cancer risk conditional cancerogens in produce of livestock fed on species of spurge (Euphorbiaceae). I. Skin irritant and tumor-promoting ingenane-type diterpene esters in E. peplus, one of several herbaceous Euphorbia species contaminating fodder of livestock. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 1998, 124, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gwak, J.; Jung, S.J.; Kang, D.I.; Kim, E.Y.; Kim, D.E.; Chung, Y.H.; Shin, J.G.; Oh, S. Stimulation of protein kinase C-alpha suppresses colon cancer cell proliferation by down-regulation of beta-catenin. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2009, 13, 2171–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshankhah, H.; Izadi, Z.; Alaei, L.; Lotfabadi, A.; Saboury, A.A.; Dinarvand, R.; Divsalar, A.; Seyedarabi, A.; Barzegari, E.; Evini, M. Colon Cancer and Specific Ways to Deliver Drugs to the Large Intestine. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 1317–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Drug Names | Selectivity | Molecule | Targeted Cancer | Phase | Number of Studies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bryostatin 1 | Classical and novel PKC | Macrolide lactone | Leukemia | I, II | 9 | |||||

| 2 fold for ε over α and δ | Naturally found in | Lymphoma | I, II | 9 | ||||||

| the Bryozoan species | Renal cancer | I, II | 7 | |||||||

| Bugula neritina | Unspecified adult tumors | I | 6 | |||||||

| Gastric cancer | II | 3 | ||||||||

| Esophageal cancer | II | 2 | ||||||||

| Melanoma (skin) | I | 2 | ||||||||

| Myeloma | II | 2 | ||||||||

| Ovarian cancer | II | 2 | ||||||||

| Breast cancer | II | 1 | ||||||||

| Cervical cancer | II | 1 | ||||||||

| Colorectal cancer | II | 1 | ||||||||

| Fallopian tube cancer | II | 1 | ||||||||

| Head and neck | II | 1 | ||||||||

| Lung cancer | II | 1 | ||||||||

| Pancreatic cancer | II | 1 | ||||||||

| Prostate cancer | II | 1 | ||||||||

| Small intestine cancer | I | 1 | ||||||||

| 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate | Classical and novel PKC | Diterpene ester | Leukemia | I, II | 2 | |||||

| Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate | α, β,γ, δ, ε, θ, η | Naturally found in | Skin neoplasms | II | 1 | |||||

| TPA, PMA | the Euphorbia | |||||||||

| Croton Tiglium | ||||||||||

| Ingenol-3-angelate PEP005 | Preferential for α and δ | Diterpene ester | Basal Cell Carcinoma | II | 4 | |||||

| Naturally found in | Lentigo Maligna | II | 1 | |||||||

| the Euphorbia Peplus | Seborrheic Keratosis | II, III | 6 | |||||||

| Squamous Cell carcinoma | II | 1 | ||||||||

; Currently recruiting participants

; Currently recruiting participants  .

.© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dupasquier, S.; Blache, P.; Picque Lasorsa, L.; Zhao, H.; Abraham, J.-D.; Haigh, J.J.; Ychou, M.; Prévostel, C. Modulating PKCα Activity to Target Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling in Colon Cancer. Cancers 2019, 11, 693. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/cancers11050693

Dupasquier S, Blache P, Picque Lasorsa L, Zhao H, Abraham J-D, Haigh JJ, Ychou M, Prévostel C. Modulating PKCα Activity to Target Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling in Colon Cancer. Cancers. 2019; 11(5):693. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/cancers11050693

Chicago/Turabian StyleDupasquier, Sébastien, Philippe Blache, Laurence Picque Lasorsa, Han Zhao, Jean-Daniel Abraham, Jody J. Haigh, Marc Ychou, and Corinne Prévostel. 2019. "Modulating PKCα Activity to Target Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling in Colon Cancer" Cancers 11, no. 5: 693. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/cancers11050693