Understanding the Biological Activities of Vitamin D in Type 1 Neurofibromatosis: New Insights into Disease Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Design

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Vitamin D: State of the Art

1.1. Vitamin D: Production and Metabolism

1.2. Vitamin D: Dietary Intake, Supplementation and Toxicity

1.3. Vitamin D: Status, Measurement and Deficiency

1.4. Correlations between Vitamin D Deficiency and Several Disorders

2. Neurofibromatosis

2.1. Genetics of NF1: NF1 Gene and Neurofibromin

2.2. NF1 Protein Isoforms

2.3. Clinical Manifestations of NF1

2.4. Clinical Diagnosis of NF1

2.5. Treatment of NF1

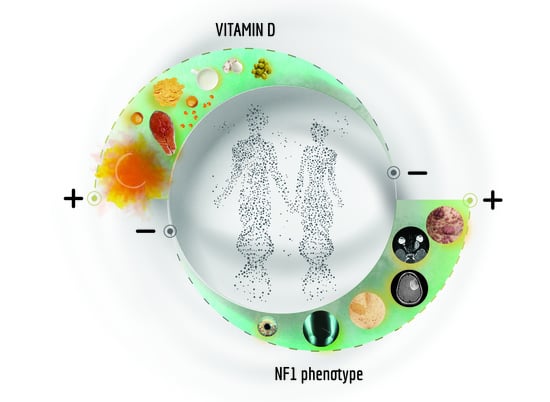

3. Vitamin D and Neurofibromatosis 1

3.1. Anticancer Effects of Vitamin D: Regulation of Multiple Signalling Networks

3.2. Vitamin D-NF1 Correlation: Clinical Evidences

3.3. Treatment of NF1: The Use of Vitamin D Alone or in Combination Therapy

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khammissa, R.A.G.; Fourie, J.; Motswaledi, M.H.; Ballyram, R.; Lemmer, J.; Feller, L. The Biological Activities of Vitamin D and Its Receptor in Relation to Calcium and Bone Homeostasis, Cancer, Immune and Cardiovascular Systems, Skin Biology, and Oral Health. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Göring, H.; Koshuchowa, S. Vitamin D—The Sun Hormone. Life in Environmental Mismatch. Biochemistry 2015, 80, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLuca, H.F. Overview of General Physiologic Features and Functions of Vitamin D. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 80, 1689S–1696S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holick, M.F. Vitamin D Deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.S.; Shoker, A. Vitamin D Metabolites; Protective versus Toxic Properties: Molecular and Cellular Perspectives. Nephrol. Res. Rev. 2010, 2, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keegan, R.-J.H.; Lu, Z.; Bogusz, J.M.; Williams, J.E.; Holick, M.F. Photobiology of Vitamin D in Mushrooms and Its Bioavailability in Humans. Dermato-Endocrinol. 2013, 5, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holick, M.F.; MacLaughlin, J.A.; Clark, M.B.; Holick, S.A.; Potts, J.T.; Anderson, R.R.; Blank, I.H.; Parrish, J.A.; Elias, P. Photosynthesis of Previtamin D3 in Human Skin and the Physiologic Consequences. Science 1980, 210, 203–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. The Cutaneous Photosynthesis of Previtamin D3: A Unique Photoendocrine System. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1981, 77, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lehmann, B.; Meurer, M. Vitamin D Metabolism. Dermatol. Ther. 2010, 23, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikle, D.D. Vitamin D Metabolism and Function in the Skin. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2011, 347, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saraff, V.; Shaw, N. Sunshine and Vitamin D. Arch. Dis. Child. 2015, 101, 190–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlberg, C. Nutrigenomics of Vitamin D. Nutrients 2019, 11, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holick, M.F. Vitamin D: A D-Lightful Health Perspective. Nutr. Rev. 2008, 66, S182–S194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, W.Z.; Hegazy, R.A. Vitamin D and the Skin: Focus on a Complex Relationship: A review. J. Adv. Res. 2015, 6, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bikle, D.D.; Christakos, S. New Aspects of Vitamin D Metabolism and Action—Addressing the Skin as Source and Target. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2020, 16, 234–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urena-Torres, P.; Souberbielle, J.C. Pharmacologic Role of Vitamin D Natural Products. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2014, 12, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacker, M.; Holick, M.F. Sunlight and Vitamin D: A global Perspective for Health. Dermato-Endocrinol. 2013, 5, 51–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kannan, S.; Lim, H. Photoprotection and Vitamin D: A Review. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2014, 30, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Delanghe, J.; Speeckaert, R.; Speeckaert, M.M. Behind the Scenes of Vitamin D Binding Protein: More Than Vitamin D Binding. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 29, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, R.; Shieh, A.; Gottlieb, C.; Yacoubian, V.; Wang, J.; Hewison, M.; Adams, J.S. Vitamin D Binding Protein and the Biological Activity of Vitamin D. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, R.; Schuit, F.; Antonio, L.; Rastinejad, F. Vitamin D Binding Protein: A Historic Overview. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 10, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanel, A.; Carlberg, C. Vitamin D and Evolution: Pharmacologic Implications. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 173, 113595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijven, P.; Soeters, P. Vitamin D: A Magic Bullet or a Myth? Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 2663–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, T.K.; Lester, G.E.; Lorenc, R.S. Evidence for Extra-Renal 1 Alpha-Hydroxylation of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 in Pregnancy. Science 1979, 204, 1311–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawer, E.B.; Hayes, M.E.; Heys, S.E.; Davies, M.; White, A.; Stewart, M.F.; Smith, G.N. Constitutive Synthesis of 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 by a Human Small Cell Lung Cancer Cell Line. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1994, 79, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, G.G.; Whitlatch, L.W.; Chen, T.C.; Lokeshwar, B.L.; Holick, M.F. Human Prostate Cells Synthesize 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 from 25-Hydroxyvitamin D. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 1998, 7, 391–395. [Google Scholar]

- Zehnder, D.; Bland, R.; Williams, M.C.; McNinch, R.W.; Howie, A.J.; Stewart, P.; Hewison, M. Extrarenal Expression of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3-1α-Hydroxylase. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 888–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Esteban, L.; Vidal, M.; Dusso, A. 1α-Hydroxylase Transactivation by γ-Interferon in Murine Macrophages Requires Enhanced C/EBPβ Expression and Activation. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004, 89, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffels, K.; Overbergh, L.; Bouillon, R.; Mathieu, C. Immune Regulation of 1α-Hydroxylase in Murine Peritoneal Macrophages: Unravelling the IFNγ Pathway. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2007, 103, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F.; Chen, T.C.; Lu, Z.; Sauter, E. Vitamin D and Skin Physiology: A D-Lightful Story. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2007, 22, V28–V33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christakos, S.; Ajibade, D.V.; Dhawan, P.; Fechner, A.J.; Mady, L.J. Vitamin D: Metabolism. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2010, 39, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G. Extrarenal Vitamin D Activation and Interactions Between Vitamin D2, Vitamin D3, and Vitamin D Analogs. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2013, 33, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikle, D.D. Vitamin D Metabolism, Mechanism of Action, and Clinical Applications. Chem. Biol. 2014, 21, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, G.; Prosser, D.E.; Kaufmann, M. Cytochrome P450- Mediated Metabolism of Vitamin D. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 55, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheng, J.B.; Levine, M.A.; Bell, N.H.; Mangelsdorf, D.J.; Russell, D.W. Genetic Evidence That the Human CYP2R1 Enzyme Is a Key Vitamin D 25-Hydroxylase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 7711–7715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gottfried, E.; Rehli, M.; Hahn, J.; Holler, E.; Andreesen, R.; Kreutz, M. Monocyte- Derived Cells Express CYP27A1 and Convert Vitamin D3 Into Its Active Metabolite. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 349, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutair, A.; Nasrat, G.H.; Russell, D.W. Mutation of the CYP2R1 Vitamin D 25-Hydroxylase in a Saudi Arabian Family with Severe Vitamin D Deficiency. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, E2022-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, J.; DeLuca, H.F. Vitamin D 25-Hydroxylase—Four Decades of Searching, Are We There Yet? Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012, 523, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.G.; Ochalek, J.T.; Kaufmann, M.; Jones, G.; DeLuca, H.F. CYP2R1 is a Major, but Not Exclusive, Contributor to 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Production In Vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 15650–15655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Christakos, S.; Dhawan, P.; Verstuyf, A.; Verlinden, L.; Carmeliet, G. Vitamin D: Metabolism, Molecular Mechanism of Action, and Pleiotropic Effects. Physiol. Rev. 2016, 96, 365–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.S.; Hewison, M. Extrarenal Expression of the 25-Hydroxyvitamin D-1-Hydroxylase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012, 523, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schlingmann, K.P.; Kaufmann, M.; Weber, S.; Irwin, A.; Goos, C.; John, U.; Misselwitz, J.; Klaus, G.; Kuwertz-Bröking, E.; Fehrenbach, H.; et al. Mutations inCYP24A1and Idiopathic Infantile Hypercalcemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.; Prosser, D.E.; Kaufmann, M. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D-24-Hydroxylase (CYP24A1): Its Important Role in the Degradation of Vitamin D. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012, 523, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson, C. The Vitamin D Metabolome: An Update on Analysis and Function. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2019, 37, 408–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuckey, R.C.; Cheng, C.Y.; Slominski, A.T. The Serum Vitamin D Metabolome: What We Know and What Is Still to Discover. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019, 186, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zohily, B.; Al Menhali, A.; Gariballa, S.; Haq, A.; Shah, I. Epimers of Vitamin D: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pludowski, P.; Holick, M.F.; Grant, W.B.; Konstantynowicz, J.; Mascarenhas, M.R.; Haq, A.; Povoroznyuk, V.; Balatska, N.; Barbosa, A.P.; Karonova, T.; et al. Vitamin D Supplementation Guidelines. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 175, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boyle, I.T.; Gray, R.W.; DeLuca, H.F. Regulation by Calcium of In Vivo Synthesis of 1,25-Dihydroxycholecalciferol and 21,25-Dihydroxycholecalciferol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1971, 68, 2131–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Omdahl, J.L.; Morris, H.A.; May, B.K. Hydroxylase Enzymes of the Vitamin D Pathway: Expression, Function, and Regulation. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2002, 22, 139–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, H.L. Parathyroid Hormone Modulation of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D 3 Metabolism by Cultured Chick Kidney Cells Is Mimicked and Enhanced by Forskolin. Endocrinology 1985, 116, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenza, H.L.; Kimmel-Jehan, C.; Jehan, F.; Shinki, T.; Wakino, S.; Anazawa, H.; Suda, T.; DeLuca, H.F. Parathyroid Hormone Activation of the 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3-1 -Hydroxylase Gene Promoter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 1387–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murayama, A.; Takeyama, K.-I.; Kitanaka, S.; Kodera, Y.; Hosoya, T.; Kato, S. The Promoter of the Human 25-Hydroxyvitamin D31α-Hydroxylase Gene Confers Positive and Negative Responsiveness to PTH, Calcitonin, and 1α,25(OH)2D. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998, 249, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, A.; Takeyama, K.-I.; Kitanaka, S.; Kodera, Y.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Hosoya, T.; Kato, S. Positive and Negative Regulations of the Renal 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 1α-Hydroxylase Gene by Parathyroid Hormone, Calcitonin, and 1α,25(OH)2D3 in Intact Animals. Endocrinology 1999, 140, 2224–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zierold, C.; Nehring, J.A.; DeLuca, H.F. Nuclear Receptor 4A2 and C/EBPβ Regulate the Parathyroid Hormone-Mediated Transcriptional Regulation of the 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3-1α-Hydroxylase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007, 460, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Dietrich, T.; Orav, E.J.; Hu, F.B.; Zhang, Y.; Karlson, E.W.; Dawson-Hughes, B. Higher 25- Hydroxyvitamin D Concentrations Are Associated With Better Lower-Extremity Function in Both Active and Inactive Persons Aged ≥ 60 y. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 80, 752–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenza, H.L.; DeLuca, H.F. Regulation of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 1α-Hydroxylase Gene Expression by Parathyroid Hormone and 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2000, 381, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-S.; Fujiki, R.; Murayama, A.; Kitagawa, H.; Yamaoka, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Mihara, M.; Takeyama, K.-I.; Kato, S. 1α,25(OH)2D3-Induced Transrepression by Vitamin D Receptor through E-Box-Type Elements in the Human Parathyroid Hormone Gene Promoter. Mol. Endocrinol. 2007, 21, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Miao, D.; Li, J.; Goltzman, D.; Karaplis, A.C. Transgenic Mice Overexpressing Human Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 (R176Q) Delineate a Putative Role for Parathyroid Hormone in Renal Phosphate Wasting Disorders. Endocrinology 2004, 145, 5269–5279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, T.; Kakitani, M.; Yamazaki, Y.; Hasegawa, H.; Takeuchi, Y.; Fujita, T.; Fukumoto, S.; Tomizuka, K.; Yamashita, T. Targeted Ablation of FGF23 Demonstrates an Essential Physiological Role of FGF23 in Phosphate and Vitamin D Metabolism. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 113, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Tang, W.; Zhou, J.; Stubbs, J.R.; Luo, Q.; Pi, M.; Quarles, L.D. Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 Is a Counter-Regulatory Phosphaturic Hormone for Vitamin D. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006, 17, 1305–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berridge, M.J. Vitamin D Cell Signalling in Health and Disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 460, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleet, J.C. The Role of Vitamin D in the Endocrinology Controlling Calcium Homeostasis. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2017, 453, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimalawansa, S.J.; Razzaque, M.S.; Al-Daghri, N.M.; Razzaque, D.M.S. Calcium and Vitamin D in Human Health: Hype or Real? J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 180, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLuca, H.F. Evolution of Our Understanding of Vitamin D. Nutr. Rev. 2008, 66, S73–S87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangelsdorf, D.J.; Thummel, C.; Beato, M.; Herrlich, P.; Schütz, G.; Umesono, K.; Blumberg, B.; Kastner, P.; Mark, M.; Chambon, P.; et al. The Nuclear Receptor Superfamily: The Second Decade. Cell 1995, 83, 835–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mangelsdorf, D.J.; Evans, R.M. The RXR Heterodimers and Orphan Receptors. Cell 1995, 83, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carlberg, C.; Bendik, I.; Wyss, A.; Meier, E.; Sturzenbecker, L.J.; Grippo, J.F.; Hunziker, W. Two Nuclear Signalling Pathways for Vitamin D. Nat. Cell Biol. 1993, 361, 657–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, J.W.; Meyer, M.B.; Watanuki, M.; Kim, S.; Zella, L.A.; Fretz, J.A.; Yamazaki, M.; Shevde, N.K. Perspectives on Mechanisms of Gene Regulation by 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 and Its Receptor. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2007, 103, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carlberg, C. Genome- Wide (Over)View on the Actions of Vitamin D. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jeon, S.-M.; Shin, E.-A. Exploring Vitamin D Metabolism and Function in Cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 2018, 50, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haussler, M.R.; Whitfield, G.K.; Haussler, C.A.; Hsieh, J.C.; Thompson, P.D.; Selznick, S.H.; Dominguez, C.E.; Jurutka, P.W. The Nuclear Vitamin D Receptor: Biological and Molecular Regulatory Properties Revealed. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1998, 410, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, L.Y.; Wortsman, J.; Dannenberg, M.J.; Hollis, B.W.; Lu, Z.; Holick, M.F. Clothing Prevents Ultraviolet-B Radiation-Dependent Photosynthesis of Vitamin D. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1992, 75, 1099–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, A.R.; Kline, L.; Holick, M.F. Influence of Season and Latitude on the Cutaneous Synthesis of Vitamin D3: Exposure to Winter Sunlight in Boston and Edmonton Will Not Promote Vitamin D3 Synthesis in Human Skin. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1988, 67, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matsuoka, L.Y.; Ide, L.; Wortsman, J.; MacLaughlin, J.A.; Holick, M.F. Sunscreens Suppress Cutaneous Vitamin D3 Synthesis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1987, 64, 1165–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Passeron, T.; Bouillon, R.; Callender, V.; Cestari, T.; Diepgen, T.; Green, A.C.; Van Der Pols, J.; Bernard, B.; Ly, F.; Bernerd, F.; et al. Sunscreen Photoprotection and Vitamin D Status. Br. J. Dermatol. 2019, 181, 916–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Green, A.; Autier, P.; Boniol, M.; Boyle, P.; Doré, J.F.; Gandini, S.; Newton-Bishop, J.; Secretan, B.; Walter, S.J.; Weinstock, M.A.; et al. The Association of Use of Sunbeds with Cutaneous Malignant Melanoma and Other Skin Cancers: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Cancer 2006, 120, 1116–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, M.S.; Whiting, S.J. Prevalence of Vitamin D Insufficiency in Canada and the United States: Importance to Health Status and Efficacy of Current Food Fortification and Dietary Supplement Use. Nutr. Rev. 2003, 61, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpowitz, D.; Gilchrest, B.A. The Vitamin D Questions: How Much Do You Need and How Should You Get It? J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2006, 54, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucock, M.; Jones, P.; Martin, C.; Beckett, E.; Yates, Z.; Furst, J.; Veysey, M. Vitamin D: Beyond Metabolism. J. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 20, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szymczak-Pajor, I.; Sliwinska, A. Analysis of Association between Vitamin D Deficiency and Insulin Resistance. Nutrients 2019, 11, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmid, A.; Walther, B. Natural Vitamin D Content in Animal Products. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendik, I.; Friedel, A.; Roos, F.F.; Weber, P.; Eggersdorfer, M. Vitamin D: A Critical and Essential Micronutrient for Human Health. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovesen, L.; Brot, C.; Jakobsen, J. Food Contents and Biological Activity of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D: A Vitamin D Metabolite to Be Reckoned With? Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2003, 47, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, M.S.; Whiting, S.J.; Barton, C.N. Vitamin D Fortification in the United States and Canada: Current Status and Data Needs. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 80, 1710S–1716S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Biancuzzo, R.M.; Young, A.; Bibuld, D.; Cai, M.H.; Winter, M.R.; Klein, E.K.; Ameri, A.; Reitz, R.; Salameh, W.A.; Chen, T.C.; et al. Fortification of Orange Juice With Vitamin D(2) or Vitamin D(3) Is as Effective as an Oral Supplement in Maintaining Vitamin D Status in Adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1621–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pilz, S.; März, W.; Cashman, K.D.; Kiely, M.E.; Whiting, S.J.; Holick, M.F.; Grant, W.B.; Pludowski, P.; Hiligsmann, M.; Trummer, C.; et al. Rationale and Plan for Vitamin D Food Fortification: A Review and Guidance Paper. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borel, P.; Caillaud, D.; Cano, N.J. Vitamin D Bioavailability: State of the Art. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 55, 1193–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Willett, W.C.; Wong, J.B.; Giovannucci, E.; Dietrich, T.; Dawson-Hughes, B. Fracture Prevention with Vitamin D Supplementation. JAMA 2005, 293, 2257–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagnoli, E.; Pepe, J.; Piemonte, S.; Cipriani, C.; Minisola, S. Management of Endocrine Disease: Value and Limitations of Assessing Vitamin D Nutritional Status and Advised Levels of Vitamin D Supplementation. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2013, 169, R59–R69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Minisola, S.; Colangelo, L.; Pepe, J.; Occhiuto, M.; Piazzolla, V.; Renella, M.; Biamonte, F.; Sonato, C.; Cilli, M.; Cipriani, C. Vitamin D screening. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2020, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang, H.M.; Cole, D.E.; A. Rubin, L.; Pierratos, A.; Siu, S.; Vieth, R. Evidence That Vitamin D3 Increases Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D More Efficiently Than Does Vitamin D2. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998, 68, 854–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Armas, L.A.; Hollis, B.W.; Heaney, R.P. Vitamin D2 Is Much Less Effective than Vitamin D3 in Humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 5387–5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Houghton, L.; Vieth, R. The Case Against Ergocalciferol (Vitamin D2) as a Vitamin Supplement. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 84, 694–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tripkovic, L.; Lambert, H.; Hart, K.; Smith, C.P.; Bucca, G.; Penson, S.; Chope, G.; Hyppönen, E.; Berry, J.; Vieth, R.; et al. Comparison of Vitamin D2 and Vitamin D3 Supplementation in Raising Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Status: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 1357–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cashman, K.D.; Seamans, K.M.; Lucey, A.J.; Stöcklin, E.; Weber, P.; Kiely, M.; Hill, T.R. Relative effectiveness of oral 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and vitamin D3 in raising wintertime serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in older adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 1350–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cannell, J.J.; Hollis, B.W.; Zasloff, M.; Heaney, R.P. Diagnosis and Treatment of Vitamin D Deficiency. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2007, 9, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. Vitamin D Status: Measurement, Interpretation, and Clinical Application. Ann. Epidemiol. 2009, 19, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hossein-Nezhad, A.; Holick, M.F. Vitamin D for Health: A Global Perspective. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2013, 88, 720–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carlberg, C. Molecular Approaches for Optimizing Vitamin D Supplementation. Vitam. Horm. 2016, 100, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowah, D.; Fan, X.; Dennett, L.; Hagtvedt, R.; Straube, S. Vitamin D Levels and Deficiency with Different Occupations: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlberg, C.; Seuter, S.; De Mello, V.D.F.; Schwab, U.; Voutilainen, S.; Pulkki, K.; Nurmi, T.; Virtanen, J.; Tuomainen, T.-P.; Uusitupa, M. Primary Vitamin D Target Genes Allow a Categorization of Possible Benefits of Vitamin D3 Supplementation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilfinger, J.; Seuter, S.; Tuomainen, T.-P.; Virtanen, J.K.; Voutilainen, S.; Nurmi, T.; De Mello, V.; Uusitupa, M.; Carlberg, C. Primary Vitamin D Receptor Target Genes as Biomarkers for the Vitamin D3 Status in the Hematopoietic System. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2014, 25, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryynänen, J.; Neme, A.; Tuomainen, T.-P.; Virtanen, J.K.; Voutilainen, S.; Nurmi, T.; De Mello, V.; Uusitupa, M.; Carlberg, C. Changes in Vitamin D Target Gene Expression in Adipose Tissue Monitor the Vitamin D Response of Human Individuals. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014, 58, 2036–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saksa, N.; Neme, A.; Ryynänen, J.; Uusitupa, M.; De Mello, V.; Voutilainen, S.; Nurmi, T.; Virtanen, J.K.; Tuomainen, T.-P.; Carlberg, C. Dissecting High From Low Responders in a Vitamin D3 Intervention Study. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015, 148, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukić, M.; Neme, A.; Seuter, S.; Saksa, N.; De Mello, V.D.F.; Nurmi, T.; Uusitupa, M.; Tuomainen, T.-P.; Virtanen, J.K.; Carlberg, C. Relevance of Vitamin D Receptor Target Genes for Monitoring the Vitamin D Responsiveness of Primary Human Cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seuter, S.; Virtanen, J.K.; Nurmi, T.; Pihlajamäki, J.; Mursu, J.; Voutilainen, S.; Tuomainen, T.-P.; Neme, A.; Carlberg, C. Molecular Evaluation of Vitamin D Responsiveness of Healthy Young Adults. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2017, 174, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlberg, C.; Haq, A. The Concept of the Personal Vitamin D Response Index. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 175, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudenkov, D.V.; Yawn, B.P.; Oberhelman, S.S.; Fischer, P.R.; Singh, R.J.; Cha, S.S.; Maxson, J.A.; Quigg, S.M.; Thacher, T.D. Changing Incidence of Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Values Above 50 ng/mL: A 10-Year Population-Based Study. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2015, 90, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tebben, P.J.; Singh, R.J.; Kumar, R. Vitamin D-Mediated Hypercalcemia: Mechanisms, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Endocr. Rev. 2016, 37, 521–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. Vitamin D Deficiency: What a Pain It Is. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2003, 78, 1457–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alshahrani, F.; Aljohani, N. Vitamin D: Deficiency, Sufficiency and Toxicity. Nutrients 2013, 5, 3605–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marcinowska-Suchowierska, E.; Kupisz-Urbańska, M.; Łukaszkiewicz, J.; Płudowski, P.; Jones, G. Vitamin D Toxicity–A Clinical Perspective. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hollis, B.W. Circulating 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Levels Indicative of Vitamin D Sufficiency: Implications for Establishing a New Effective Dietary Intake Recommendation for Vitamin D. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, G. Metabolism and Biomarkers of Vitamin D. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. Suppl. 2012, 243, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuprykov, O.; Chen, X.; Hocher, C.-F.; Skoblo, R.; Yin, L.; Hocher, B. Why Should We Measure Free 25(OH) Vitamin D? J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 180, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikle, D.D.; Siiteri, P.K.; Ryzen, E.; Haddad, J.; Gee, E. Serum Protein Binding of 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D: A Reevaluation by Direct Measurement of Free Metabolite Levels. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1985, 61, 969–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G. Pharmacokinetics of Vitamin D Toxicity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 582S–586S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hughes, M.R.; Baylink, D.J.; Jones, P.G.; Haussler, M.R. Radioligand Receptor Assay for 25-Hydroxyvitamin D2/D3 and 1 Alpha, 25-Dihydroxyvitamin D2/D. J. Clin. Investig. 1976, 58, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sempos, C.T.; Heijboer, A.C.; Bikle, D.D.; Bollerslev, J.; Bouillon, R.; Brannon, P.M.; DeLuca, H.F.; Jones, G.; Munns, C.F.; Bilezikian, J.P.; et al. Vitamin D Assays and the Definition of Hypovitaminosis D: Results from the First International Conference on Controversies in Vitamin D. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 84, 2194–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.C.; Manson, J.E.; Abrams, S.A.; Aloia, J.F.; Brannon, P.M.; Clinton, S.K.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.A.; Gallagher, J.C.; Gallo, R.L.; Jones, G.; et al. The 2011 Report on Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: What Clinicians Need to Know. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordelon, P.; Ghetu, M.V.; Langan, R.C. Recognition and Management of Vitamin D Deficiency. Am. Fam. Physician 2009, 80, 841–846. [Google Scholar]

- Cashman, K.D.; Kiely, M.; Kinsella, M.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.A.; Tian, L.; Zhang, Y.; Lucey, A.J.; Flynn, A.; Gibney, M.J.; Vesper, H.W.; et al. Evaluation of Vitamin D Standardization Program Protocols for Standardizing Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Data: A Case Study of the Program’s Potential for National Nutrition and Health Surveys. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 1235–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sempos, C.T.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.; Binkley, N.; Jones, J.; Merkel, J.; Carter, G. Developing Vitamin D Dietary Guidelines and the Lack of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Assay Standardization: The Ever-Present Past. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016, 164, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. High Prevalence of Vitamin D Inadequacy and Implications for Health. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2006, 81, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holick, M.F. The Vitamin D Deficiency Pandemic: Approaches for Diagnosis, Treatment and Prevention. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2017, 18, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movassaghi, M.; Bianconi, S.; Feinn, R.; Wassif, C.A.; Porter, F.D. Vitamin D Levels in Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2017, 173, 2577–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molin, A.; Wiedemann, A.; Demers, N.; Kaufmann, M.; Cao, J.D.; Mainard, L.; Dousset, B.; Journeau, P.; Abeguile, G.; Coudray, N.; et al. Vitamin D-Dependent Rickets Type 1B (25-Hydroxylase Deficiency): A Rare Condition or a Misdiagnosed Condition? J. Bone Miner. Res. 2017, 32, 1893–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, D.; Kooh, S.W.; Kind, H.P.; Holick, M.F.; Tanaka, Y.; DeLuca, H.F. Pathogenesis of Hereditary Vitamin-D-Dependent Rickets. N. Engl. J. Med. 1973, 289, 817–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, R.; Carmeliet, G. Vitamin D Insufficiency: Definition, Diagnosis and Management. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 32, 669–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J. Dietary Vitamin D, Vitamin D Receptor, and Microbiome. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2018, 21, 471–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindh, J.D.; Björkhem-Bergman, L.; Eliasson, E. Vitamin D and Drug-Metabolising Enzymes. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2012, 11, 1797–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robien, K.; Oppeneer, S.J.; Kelly, J.A.; Hamilton-Reeves, J.M. Drug–Vitamin D Interactions. Nutr. Clin. Pr. 2013, 28, 194–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peng, J.; Liu, Y.; Xie, J.; Yang, G.; Huang, Z. Effects of Vitamin D on Drugs: Response and Disposal. Nutrients 2020, 74, 110734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. Vitamin D and Bone Health. J. Nutr. 1996, 126, 1159S–1164S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, R.P. Vitamin D in Health and Disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008, 3, 1535–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grant, W.B. The Health Benefits of Solar Irradiance and Vitamin D and the Consequences of Their Deprivation. Clin. Rev. Bone Miner. Metab. 2009, 7, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikle, D.D. Vitamin D: An Ancient Hormone. Exp. Dermatol. 2010, 20, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, J.W.; Christakos, S. Biology and Mechanisms of Action of the Vitamin D Hormone. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 46, 815–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. Vitamin D: The Underappreciated D-Lightful Hormone That Is Important for Skeletal and Cellular Health. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2002, 9, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. Sunlight and Vitamin D for Bone Health and Prevention of Autoimmune Diseases, Cancers, and Cardiovascular Disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 80, 1678S–1688S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, J.E.; Pichiah, P.T.; Cha, Y.-S. Vitamin D and Metabolic Diseases: Growing Roles of Vitamin D. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 2018, 27, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wharton, B.; Bishop, N. Rickets. Lancet 2003, 362, 1389–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. Resurrection of Vitamin D Deficiency and Rickets. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 2062–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- O’Riordan, J.L.H.; Bijvoet, O.L.M. Rickets Before the Discovery of Vitamin D. BoneKEy Rep. 2014, 3, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hill, T.R.; Aspray, T.; Francis, R.M. Vitamin D and Bone Health Outcomes in Older Age. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2013, 72, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yousef, G.M.; Azzouz, L.; Noël, C.; Lafage-Proust, M.-H. Osteomalacia Induced by Vitamin D Deficiency in Hemodialysis Patients: The Crucial Role of Vitamin D Correction. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2013, 32, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitanaka, S.; Takeyama, K.-I.; Murayama, A.; Sato, T.; Okumura, K.; Nogami, M.; Hasegawa, Y.; Niimi, H.; Yanagisawa, J.; Tanaka, T.; et al. Inactivating Mutations in the 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 1α-Hydroxylase Gene in Patients with Pseudovitamin D–Deficiency Rickets. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 338, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikle, D. Nonclassic Actions of Vitamin D. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wimalawansa, S.J. Non- Musculoskeletal Benefits of Vitamin D. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 175, 60–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-W.; Lee, H.-C. Vitamin D and Health—the Missing Vitamin in Humans. Pediatr. Neonatol. 2019, 60, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Borchers, M.; Gudat, F.; Dürmüller, U.; Stähelin, H.B.; Dick, W. Vitamin D Receptor Expression in Human Muscle Tissue Decreases with Age. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2004, 19, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilsanz, V.; Kremer, A.; Mo, A.O.; Wren, T.A.L.; Kremer, R. Vitamin D Status and Its Relation to Muscle Mass and Muscle Fat in Young Women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 1595–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stockton, K.; Mengersen, K.; Paratz, J.D.; Kandiah, D.A.; Bennell, K.L. Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Muscle Strength: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Osteoporos. Int. 2010, 22, 859–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makibayashi, K.; Tatematsu, M.; Hirata, M.; Fukushima, N.; Kusano, K.; Ohashi, S.; Abe, H.; Kuze, K.; Fukatsu, A.; Kita, T.; et al. A Vitamin D Analog Ameliorates Glomerular Injury on Rat Glomerulonephritis. Am. J. Pathol. 2001, 158, 1733–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Y.C. Vitamin D Regulation of the Renin-Angiotensin System. J. Cell. Biochem. 2002, 88, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Sun, L.; Wang, Y.; Ning, G.; Minto, A.; Kong, J.; Quigg, R.; Li, Y.C. Renoprotective Role of the Vitamin D Receptor in Diabetic Nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2008, 73, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Kong, J.; Deb, D.K.; Chang, A.; Li, Y.C. Vitamin D Receptor Attenuates Renal Fibrosis by Suppressing the Renin-Angiotensin System. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 21, 966–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hyppönen, E.; Läärä, E.; Reunanen, A.; Järvelin, M.-R.; Virtanen, S.M. Intake of Vitamin D and Risk of Type 1 Diabetes: A Birth-Cohort Study. Lancet 2001, 358, 1500–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littorin, B.; Blom, P.; Schölin, A.; Arnqvist, H.J.; Blohmé, G.; Bolinder, J.; Ekbom-Schnell, A.; Eriksson, J.W.; Gudbjörnsdottir, S.; Nyström, L.; et al. Lower Levels of Plasma 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Among Young Adults at Diagnosis of Autoimmune Type 1 Diabetes Compared With Control Subjects: Results From the Nationwide Diabetes Incidence Study in Sweden (DISS). Diabetologia 2006, 49, 2847–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zipitis, C.S.; Akobeng, A.K. Vitamin D supplementation in Early Childhood and Risk of Type 1 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch. Dis. Child. 2008, 93, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mitri, J.; Pittas, A.G. Vitamin D and Diabetes. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 43, 205–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Angellotti, E.; Pittas, A.G. The Role of Vitamin D in the Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes: To D or Not to D? Endocrinology 2017, 158, 2013–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berridge, M.J. Vitamin D Deficiency and Diabetes. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 1321–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahebkar, A.; Maleki, M.; Sathyapalan, T.; Iranpanah, H.; Orafai, H.M.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. The Molecular Mechanisms by Which Vitamin D Improve Glucose Homeostasis: A Mechanistic Review. Life Sci. 2020, 244, 117305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimalawansa, S.J. Associations of Vitamin D With Insulin Resistance, Obesity, Type 2 Diabetes, and Metabolic Syndrome. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 175, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakharova, I.; Klimov, L.; Kuryaninova, V.; Nikitina, I.; Malyavskaya, S.; Dolbnya, S.; Kasyanova, A.; Atanesyan, R.; Stoyan, M.; Todieva, A.; et al. Vitamin D Insufficiency in Overweight and Obese Children and Adolescents. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bassatne, A.; Chakhtoura, M.; Saad, R.K.; Fuleihan, G.E.-H. Vitamin D Supplementation in Obesity and During Weight Loss: A Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Metabolism 2019, 92, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosdou, J.K.; Konstantinidou, E.; Anagnostis, P.; Kolibianakis, E.M.; Goulis, D.G. Vitamin D and Obesity: Two Interacting Players in the Field of Infertility. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ferri, E.; Casati, M.; Cesari, M.; Vitale, G.; Arosio, B. Vitamin D in Physiological and Pathological Aging: Lesson from Centenarians. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2019, 20, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Layana, A.; Minnella, A.M.; Garhöfer, G.; Aslam, T.; Holz, F.G.; Leys, A.; Silva, R.; Delcourt, C.; Souied, E.; Seddon, J.M. Vitamin D and Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bodnar, L.M.; Catov, J.M.; Simhan, H.N.; Holick, M.F.; Powers, R.W.; Roberts, J.M. Maternal Vitamin D Deficiency Increases the Risk of Preeclampsia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 92, 3517–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, C.; Qiu, C.; Hu, F.B.; David, R.M.; Van Dam, R.M.; Bralley, A.; Williams, M.A. Maternal Plasma 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentrations and the Risk for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shin, J.S.; Choi, M.Y.; Longtine, M.S.; Nelson, D.M. Vitamin D Effects on Pregnancy and the Placenta. Placenta 2010, 31, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hollis, B.W.; Johnson, D.; Hulsey, T.C.; Ebeling, M.; Wagner, C.L. Vitamin D Supplementation During Pregnancy: Double-Blind, Randomized Clinical Trial of Safety and Effectiveness. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2011, 26, 2341–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Knabl, J.; Vattai, A.; Ye, Y.; Jueckstock, J.; Hutter, S.; Kainer, F.; Mahner, S.; Jeschke, U. Role of Placental VDR Expression and Function in Common Late Pregnancy Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Purswani, J.M.; Gala, P.; Dwarkanath, P.; Larkin, H.M.; Kurpad, A.V.; Mehta, S. The Role of Vitamin D in Pre-Eclampsia: A Systematic Review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ganguly, A.; Tamblyn, J.A.; Finn-Sell, S.L.; Chan, S.Y.; Westwood, M.; Gupta, J.; Kilby, M.D.; Gross, S.R.; Hewison, M. Vitamin D, The Placenta and Early Pregnancy: Effects on Trophoblast Function. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 236, R93–R103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, W.G.; Nuyt, A.M.; Weiler, H.; LeDuc, L.; Santamaria, C.; Wei, S.Q. Association Between Vitamin D Supplementation During Pregnancy and Offspring Growth, Morbidity, and Mortality. JAMA Pediatr. 2018, 172, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karras, S.N.; Wagner, C.L.; Castracane, V.D. Understanding Vitamin D Metabolism in Pregnancy: From Physiology to Pathophysiology and Clinical Outcomes. Metabolism 2018, 86, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Sabour, S.; Sagar, U.N.; Adams, S.; Whellan, D.J. Prevalence of Hypovitaminosis D in Cardiovascular Diseases (from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001 to 2004). Am. J. Cardiol. 2008, 102, 1540–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.L.; May, H.T.; Horne, B.D.; Bair, T.L.; Hall, N.L.; Carlquist, J.F.; Lappé, N.L.; Muhlestein, J.B. Relation of Vitamin D Deficiency to Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Disease Status, and Incident Events in a General Healthcare Population. Am. J. Cardiol. 2010, 106, 963–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandenburg, V.M.; Vervloet, M.G.; Marx, N. The Role of Vitamin D in Cardiovascular Disease: from Present Evidence to Future Perspectives. Atherosclerosis 2012, 225, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vacek, J.L.; Vanga, S.R.; Good, M.; Lai, S.M.; Lakkireddy, D.; Howard, P.A. Vitamin D Deficiency and Supplementation and Relation to Cardiovascular Health. Am. J. Cardiol. 2012, 109, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saponaro, F.; Marcocci, C.; Zucchi, R. Vitamin D Status and Cardiovascular Outcome. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2019, 42, 1285–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danik, J.S.; Manson, J.E. Vitamin D and Cardiovascular Disease. Curr. Treat. Opt. Cardiovasc. Med. 2012, 14, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, P.T.; Stenger, S.; Li, H.; Wenzel, L.; Tan, B.H.; Krutzik, S.R.; Ochoa, M.T.; Schauber, J.; Wu, K.; Meinken, C.; et al. Toll-Like Receptor Triggering of a Vitamin D-Mediated Human Antimicrobial Response. Science 2006, 311, 1770–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamshchikov, A.V.; Desai, N.S.; Blumberg, H.M.; Ziegler, T.R.; Tangpricha, V. Vitamin D for Treatment and Prevention of Infectious Diseases: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Endocr. Pract. 2009, 15, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Urashima, M.; Segawa, T.; Okazaki, M.; Kurihara, M.; Wada, Y.; Ida, H. Randomized Trial of Vitamin D Supplementation to Prevent Seasonal Influenza a in Schoolchildren. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1255–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kearns, M.D.; Alvarez, J.A.; Seidel, N.; Tangpricha, V. Impact of Vitamin D on Infectious Disease. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 349, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jorde, R.; Sollid, S.T.; Svartberg, J.; Joakimsen, R.M.; Grimnes, G.; Hutchinson, M.Y.S. Prevention of Urinary Tract Infections with Vitamin D Supplementation 20,000 IU per Week for Five Years. Results from an RCT Including 511 Subjects. Infect. Dis. 2016, 48, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantorna, M.T.; Mahon, B.D. Mounting Evidence for Vitamin D as an Environmental Factor Affecting Autoimmune Disease Prevalence. Exp. Biol. Med. 2004, 229, 1136–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdaca, G.; Tonacci, A.; Negrini, S.; Greco, M.; Borro, M.; Puppo, F.; Gangemi, S. Emerging Role of Vitamin D in Autoimmune Diseases: An Update on Evidence and Therapeutic Implications. Autoimmun. Rev. 2019, 18, 102350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslam, M.M.; John, P.; Bhatti, A.; Jahangir, S.; Kamboh, M.I. Vitamin D as a Principal Factor in Mediating Rheumatoid Arthritis-Derived Immune Response. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Harrison, S.R.; Li, D.; Jeffery, L.E.; Raza, K.; Hewison, M. Vitamin D, Autoimmune Disease and Rheumatoid Arthritis. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2019, 106, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mudambi, K.; Bass, D. Vitamin D: A Brief Overview of Its Importance and Role in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Transl. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 3, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parizadeh, S.M.; Jafarzadeh-Esfehani, R.; Hassanian, S.M.; Mottaghi-Moghaddam, A.; Ghazaghi, A.; Ghandehari, M.; Alizade-Noghani, M.; Khazaei, M.; Ghayour-Mobarhan, M.; Ferns, G.A.; et al. Vitamin D in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: From Biology to Clinical Implications. Complement. Ther. Med. 2019, 47, 102189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, J.; Cooper, S.C.; Ghosh, S.; Hewison, M. The Role of Vitamin D in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Mechanism to Management. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Olmedo-Martín, R.V.; González-Molero, I.; Olveira, G.; Amo-Trillo, V.; Jiménez-Pérez, M. Vitamin D in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Biological, Clinical and Therapeutic Aspects. Curr. Drug Metab. 2019, 20, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Sun, M.-H.; Chen, F.; Li, J.-R. Vitamin D Levels in Systemic Sclerosis Patients: A Meta-Analysis. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2017, 11, 3119–3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elkama, A.; Karahalil, B. Role of Gene Polymorphisms in Vitamin D Metabolism and in Multiple Sclerosis. Arch. Ind. Hyg. Toxicol. 2018, 69, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Voo, V.T.F.; O’Brien, T.; Butzkueven, H.; Monif, M. The Role of Vitamin D and P2X7R in Multiple Sclerosis. J. Neuroimmunol. 2019, 330, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolders, J.; Torkildsen, Ø.; Camu, W.; Holmøy, T. An Update on Vitamin D and Disease Activity in Multiple Sclerosis. CNS Drugs 2019, 33, 1187–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, D. The Role of Vitamin D in Thyroid Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cui, X.; Gooch, H.; Petty, A.; McGrath, J.J.; Eyles, D. Vitamin D and the Brain: Genomic and Non-Genomic Actions. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2017, 453, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyles, D.; Burne, T.H.; McGrath, J.J. Vitamin D, Effects on Brain Development, Adult Brain Function and the Links Between Low Levels of Vitamin D and Neuropsychiatric Disease. Front. Neuroendocr. 2013, 34, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Somma, C.; Scarano, E.; Barrea, L.; Zhukouskaya, V.V.; Savastano, S.; Mele, C.; Scacchi, M.; Aimaretti, G.; Colao, A.; Marzullo, P. Vitamin D and Neurological Diseases: An Endocrine View. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moretti, R.; Morelli, M.E.; Caruso, P. Vitamin D in Neurological Diseases: A Rationale for a Pathogenic Impact. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bivona, G.; Gambino, C.M.; Iacolino, G.; Ciaccio, M. Vitamin D and the Nervous System. Neurol. Res. 2019, 41, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landel, V.; Annweiler, C.; Millet, P.; Morello, M.; Feron, F. Vitamin D, Cognition and Alzheimer’s Disease: The Therapeutic Benefit is in the D-Tails. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2016, 53, 419–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Câmara, A.B.; De Souza, I.D.; Dalmolin, R.J.S. Sunlight Incidence, Vitamin D Deficiency, and Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Med. Food 2018, 21, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun, E.; Gezen-Ak, D. Vitamin D basis of Alzheimer’s Disease: From Genetics to Biomarkers. Hormones 2018, 18, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimmelzwaan, L.M.; Van Schoor, N.M.; Lips, P.; Berendse, H.W.; Eekhoff, E.M.W. Systematic Review of the Relationship between Vitamin D and Parkinson’s Disease. J. Park. Dis. 2016, 6, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sleeman, I.; Aspray, T.; Lawson, R.; Coleman, S.; Duncan, G.; Khoo, T.K.; Schoenmakers, I.; Rochester, L.; Burn, D.; Yarnall, A. The Role of Vitamin D in Disease Progression in Early Parkinson’s Disease. J. Park. Dis. 2017, 7, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, Z.; Li, K. The Association Between Vitamin D Status, Vitamin D Supplementation, Sunlight Exposure, and Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Med. Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 666–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleet, J.C.; Desmet, M.; Johnson, R.; Li, Y. Vitamin D and Cancer: A Review of Molecular Mechanisms. Biochem. J. 2011, 441, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yin, L.; Ordóñez-Mena, J.M.; Chen, T.; Schöttker, B.; Arndt, V.; Brenner, H. Circulating 25- Hydroxyvitamin D Serum Concentration and Total Cancer Incidence and Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Prev. Med. 2013, 57, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, D.; Krishnan, A.V.; Swami, S.; Giovannucci, E.; Feldman, B.J. The Role of Vitamin D in Reducing Cancer Risk and Progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 342–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, M.J.; Trump, D.L. Vitamin D Receptor Signaling and Cancer. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 46, 1009–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.B. Vitamin D, Cancer, and Dysregulated Phosphate Metabolism. Endocrine 2019, 65, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, J. Function of the Vitamin D Endocrine System in Mammary Gland and Breast Cancer. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2017, 453, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atoum, M.F.; Alzoughool, F. Vitamin D and Breast Cancer: Latest Evidence and Future Steps. Breast Cancer: Basic Clin. Res. 2017, 11, 1178223417749816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Welsh, J. Vitamin D and Breast Cancer: Past and Present. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 177, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De La Puente, M.; Cuadrado-Cenzual, M.A.; Ciudad-Cabañas, M.J.; Hernández-Cabria, M.; Collado-Yurrita, L. Vitamin D: And Its Role in Breast Cancer. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2018, 34, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Guo, J.; Xie, W.; Yuan, L.; Sheng, X. The Role of Vitamin D in Ovarian Cancer: Epidemiology, Molecular Mechanism and Prevention. J. Ovarian Res. 2018, 11, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dovnik, A.; Dovnik, N.F. Vitamin D and Ovarian Cancer: Systematic Review of the Literature with a Focus on Molecular Mechanisms. Cells 2020, 9, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Slominski, A.T.; Brożyna, A.A.; Zmijewski, M.A.; Jóźwicki, W.; Jetten, A.M.; Mason, R.S.; Tuckey, R.C.; Elmets, C.A. Vitamin D Signaling and MelanomA: Role of Vitamin D and Its Receptors in Melanoma Progression and Management. Lab. Investig. 2017, 97, 706–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slominski, A.T.; Brożyna, A.A.; Skobowiat, C.; Zmijewski, M.A.; Kim, T.-K.; Janjetovic, Z.; Oak, A.S.; Jozwicki, W.; Jetten, A.M.; Mason, R.S.; et al. On the Role of Classical and Novel Forms of Vitamin D in Melanoma Progression and Management. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 177, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brożyna, A.A.; Hoffman, R.M.; Slominski, A.T. Relevance of Vitamin D in Melanoma Development, Progression and Therapy. Anticancer Res. 2020, 40, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vishlaghi, N.; Lisse, T.S. Exploring Vitamin D Signalling Within Skin Cancer. Clin. Endocrinol. 2020, 92, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, J. Vitamin D3 and Neurofibromatosis Type 1. In A Critical Evaluation of Vitamin D—Clinical Overview; Gowder, S., Ed.; BoD: McFarland, WI, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, K.P.; Korf, B.R.; Theos, A. Neurofibromatosis Type 1. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2009, 61, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferner, R.E. The Neurofibromatoses. Pract. Neurol. 2010, 10, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhlmann, E.J.; Plotkin, S.R. Results and Problems in Cell Differentiation. In Neurofibromatoses; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, M.; Kresak, J.L. Neurofibromatosis: A Review of NF1, NF2, and Schwannomatosis. J. Pediatr. Genet. 2016, 5, 098–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ardern-Holmes, S.; Fisher, G.; North, K. Neurofibromatosis Type 2. J. Child Neurol. 2016, 32, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, A.; Plotkin, S.R. Neurofibromatosis and Schwannomatosis. Semin. Neurol. 2018, 38, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, D.; Parry, A.; Evans, D.G. Neurofibromatosis Type 2 and Related Disorders. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2019, 31, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlawat, S.; Blakeley, J.O.; Langmead, S.; Belzberg, A.J.; Fayad, L.M. Current Status and Recommendations for Imaging in Neurofibromatosis Type 1, Neurofibromatosis Type 2, and Schwannomatosis. Skelet. Radiol. 2019, 49, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauen, K.A. The RASopathies. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2013, 14, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ratner, N.; Miller, S.J. A RASopathy Gene Commonly Mutated in Cancer: The Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Tumour Suppressor. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pevec, U.; Rozman, N.; Gorsek, B.; Kunej, T. RASopathies: Presentation at the Genome, Interactome, and Phenome Levels. Mol. Syndromol. 2016, 7, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Peltonen, S.; Kallionpää, R.; Peltonen, J. Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1) Gene: Beyond Café Au Lait Spots and Dermal Neurofibromas. Exp. Dermatol. 2016, 26, 645–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Friedman, J.M. Epidemiology of Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1999, 89, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viskochil, D. Review Article: Genetics of Neurofibromatosis 1 and the NF1 Gene. J. Child Neurol. 2002, 17, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-J.; Stephenson, D.A. Recent Developments in Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2007, 20, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, V.C.; Lucas, J.; Babcock, M.A.; Gutmann, D.H.; Korf, B.; Maria, B.L. Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Revisited. Pediatrics 2009, 123, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gutmann, D.H.; Ferner, R.E.; Listernick, R.H.; Korf, B.R.; Wolters, P.L.; Johnson, K.J. Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2017, 3, 17004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaconji, T.; Whist, E.; Jamieson, R.V.; Flaherty, M.P.; Grigg, J.R.B. Neurofibromatosis Type 1: Review and Update on Emerging Therapies. Asia-Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 8, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, D.; Wright, E.; Nguyen, K.; Cannon, L.; Fain, P.; Goldgar, D.; Bishop, D.; Carey, J.; Baty, B.; Kivlin, J.; et al. Gene for von Recklinghausen Neurofibromatosis Is in the Pericentromeric Region of Chromosome. Science 1987, 236, 1100–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cawthon, R.M.; Weiss, R.; Xu, G.; Viskochil, D.; Culver, M.; Stevens, J.; Robertson, M.; Dunn, D.; Gesteland, R.; O’Connell, P.; et al. A Major Segment of the Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Gene: cDNA Sequence, Genomic Structure, and Point Mutations. Cell 1990, 62, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, M.R.; A Marchuk, D.; Andersen, L.B.; Letcher, R.; Odeh, H.M.; Saulino, A.M.; Fountain, J.W.; Brereton, A.; Nicholson, J.; Mitchell, A.L.; et al. Type 1 Neurofibromatosis Gene: Identification of a Large Transcript Disrupted in Three NF1 Patients. Science 1990, 249, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutmann, D.H.; Wood, D.L.; Collins, F.S. Identification of the Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Gene Product. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 9658–9662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- DeClue, J.E.; Cohen, B.D.; Lowy, D.R. Identification and Characterization of the Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Protein Product. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 9914–9918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shen, M.H.; Harper, P.S.; Upadhyaya, M. Molecular Genetics of Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1). J. Med. Genet. 1996, 33, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Theos, A.; Korf, B.R. Pathophysiology of Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Ann. Intern. Med. 2006, 144, 842–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Messiaen, L.M.; Callens, T.; Mortier, G.; Beysen, D.; Vandenbroucke, I.; Van Roy, N.; Speleman, F.; De Paepe, A. Exhaustive Mutation Analysis of the NF1 Gene Allows Identification of 95% of Mutations and Reveals a High Frequency of Unusual Splicing Defects. Hum. Mutat. 2000, 15, 541–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ars, E.; Kruyer, H.; Morell, M.; Pros, E.; Serra, E.; Ravella, A.; Estivill, X.; Lázaro, C. Recurrent Mutations in the NF1 Gene Are Common Among Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Patients. J. Med. Genet. 2003, 40, e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sehgal, V.N.; Verma, P.; Chatterjee, K. Type 1 Neurofibromatosis (Von Recklinghausen Disease). Cutis 2015, 96, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, T.; Piluso, G.; Saracino, D.; Uccello, R.; Schettino, C.; Dato, C.; Capaldo, G.; Giugliano, T.; Varriale, B.; Paolisso, G.; et al. A Novel Diagnostic Method to Detect Truncated Neurofibromin in Neurofibromatosis. J. Neurochem. 2015, 135, 1123–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jouhilahti, E.-M.; Peltonen, S.; Heape, A.M.; Peltonen, J. The Pathoetiology of Neurofibromatosis. Am. J. Pathol. 2011, 178, 1932–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daston, M.M.; Scrable, H.; Nordlund, M.; Sturbaum, A.K.; Nissen, L.M.; Ratner, N. The Protein Product of the Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Gene Is Expressed at Highest Abundance in Neurons, Schwann Cells, and Oligodendrocytes. Neuron 1992, 8, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, S.A.; Friedman, J.M. NF1 Gene and Neurofibromatosis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2000, 151, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Milburn, M.V.; Tong, L.; Devos, A.M.; Brunger, A.; Yamaizumi, Z.; Nishimura, S.; Kim, S.H. Molecular Switch for Signal Transduction: Structural Differences Between Active and Inactive Forms of Protooncogenic Ras Proteins. Science 1990, 247, 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xu, G.; O’Connell, P.; Viskochil, D.; Cawthon, R.; Robertson, M.; Culver, M.; Dunn, D.; Stevens, J.; Gesteland, R.; White, R.; et al. The Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Gene Encodes a Protein Related to GAP. Cell 1990, 62, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, T.N.; Gutmann, D.H.; Fletcher, J.A.; Glover, T.W.; Collins, F.S.; Downward, J. Aberrant Regulation of Ras Proteins in Malignant Tumour Cells from Type 1 Neurofibromatosis Patients. Nat. Cell Biol. 1992, 356, 713–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raught, B.; Gingras, A.C.; Sonenberg, N. The Target of Rapamycin (TOR) Proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 7037–7044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fingar, D.C.; Blenis, J. Target of Rapamycin (TOR): An Integrator of Nutrient and Growth Factor Signals and Coordinator of Cell Growth and Cell Cycle Progression. Oncogene 2004, 23, 3151–3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hay, N.; Sonenberg, N. Upstream and Downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 2004, 18, 1926–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dasgupta, B. Proteomic Analysis Reveals Hyperactivation of the Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Pathway in Neurofibromatosis 1-Associated Human and Mouse Brain Tumors. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 2755–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johannessen, C.M.; Reczek, E.E.; James, M.F.; Brems, H.; Legius, E.; Cichowski, K. The NF1 Tumor Suppressor Critically Regulates TSC2 and mTOR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 8573–8578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Trovó-Marqui, A.B.; Tajara, E.H. Neurofibromin: A General Outlook. Clin. Genet. 2006, 70, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeClue, J.E.; Papageorge, A.G.; Fletcher, J.A.; Diehl, S.R.; Ratner, N.; Vass, W.C.; Lowy, D.R. Abnormal Regulation of Mammalian p21ras Contributes to Malignant Tumor Growth in Von Recklinghausen (Type 1) Neurofibromatosis. Cell 1992, 69, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.A.; Rosenbaum, T.; Marchionni, M.A.; Ratner, N.; DeClue, J.E. Schwann Cells from Neurofibromin Deficient Mice Exhibit Activation of p21ras, Inhibition of Cell Proliferation and Morphological Changes. Oncogene 1995, 11, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bollag, G.; Clapp, D.W.; Shih, S.; Adler, F.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Thompson, P.; Lange, B.J.; Freedman, M.H.; McCormick, F.; Jacks, T.; et al. Loss of NF1 results in activation of the Ras signaling pathway and leads to aberrant growth in haematopoietic cells. Nat. Genet. 1996, 12, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, A.; Lau, N.; Gutmann, D.; Pawson, A.; Boss, G. RAS-GTP Levels Are Elevated in Human NF1 Peripheral Nerve Tumors. Oncogene 1996, 12, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, B.; Bollag, G.; Shannon, K. Hyperactive Ras as a Therapeutic Target in Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1999, 89, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldkamp, M.M.; Angelov, L.; Guha, A. Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Peripheral Nerve Tumors: Aberrant Activation of the Ras Pathway. Surg. Neurol. 1999, 51, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.D.; Der, C.J. Ras History: The Saga Continues. Small GTPases 2010, 1, 2–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hannan, F.; Ho, I.; Tong, J.J.; Zhu, Y.; Nurnberg, P.; Zhong, Y. Effect of Neurofibromatosis Type I Mutations on a Novel Pathway for Adenylyl Cyclase Activation Requiring Neurofibromin and Ras. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006, 15, 1087–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- King, J.A.J.; Straffon, A.F.L.; D’Abaco, G.M.; Poon, C.L.C.; Stacey, T.T.I.; Smith, C.M.; Buchert, M.; Corcoran, N.M.; Hall, N.E.; Callus, B.A.; et al. Distinct Requirements for the Sprouty Domain for Functional Activity of Spred Proteins. Biochem. J. 2005, 388, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stowe, I.B.; Mercado, E.L.; Stowe, T.R.; Bell, E.L.; Oses-Prieto, J.; Hernández, H.; Burlingame, A.L.; McCormick, F. A Shared Molecular Mechanism Underlies the Human Rasopathies Legius Syndrome and Neurofibromatosis. Genes Dev. 2012, 26, 1421–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hirata, Y.; Brems, H.; Suzuki, M.; Kanamori, M.; Okada, M.; Morita, R.; Llano-Rivas, I.; Ose, T.; Messiaen, L.; Legius, E.; et al. Interaction between a Domain of the Negative Regulator of the Ras-ERK Pathway, SPRED1 Protein, and the GTPase-activating Protein-related Domain of Neurofibromin Is Implicated in Legius Syndrome and Neurofibromatosis Type 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 291, 3124–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lobbous, M.; Bernstock, J.D.; Coffee, E.; Friedman, G.K.; Metrock, L.K.; Chagoya, G.; Elsayed, G.; Nakano, I.; Hackney, J.R.; Korf, B.R.; et al. An Update on Neurofibromatosis Type 1-Associated Gliomas. Cancers 2020, 12, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, Y.; O’Connell, P.; Breidenbach, H.H.; Cawthon, R.; Stevens, J.; Xu, G.; Neil, S.; Robertson, M.; White, R.; Viskochil, D. Genomic Organization of the Neurofibromatosis 1 Gene (NF1). Genomics 1995, 25, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffzek, K.; Welti, S. Neurofibromin: Protein Domains and Functional Characteristics. In Neurofibromatosis Type 1: Molecular and Cellular Biology; Upadhyaya, M., Cooper, D., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 305–326. [Google Scholar]

- Ballester, R.; Marchuk, D.; Boguski, M.; Saulino, A.; Letcher, R.; Wigler, M.; Collins, F. The NF1 Locus Encodes a Protein Functionally Related to Mammalian GAP and Yeast IRA Proteins. Cell 1990, 63, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scheffzek, K.; Ahmadian, M.R.; Kabsch, W.; Wiesmüller, L.; Lautwein, A.; Schmitz, F.; Wittinghofer, A. The Ras-RasGAP Complex: Structural Basis for GTPase Activation and Its Loss in Oncogenic Ras Mutants. Science 1997, 277, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ahmadian, M.R.; Stege, P.; Scheffzek, K.; Wittinghofer, A. Confirmation of the Arginine-Finger Hypothesis for the GAP-Stimulated GTP-Hydrolysis Reaction of Ras. Nat. Genet. 1997, 4, 686–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resat, H.; Straatsma, T.P.; Dixon, D.A.; Miller, J.H. The Arginine Finger of RasGAP Helps Gln-61 Align the Nucleophilic Water in Gap-Stimulated Hydrolysis of GTP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 6033–6038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmadian, M.R.; Kiel, C.; Stege, P.; Scheffzek, K. Structural Fingerprints of the Ras-GTPase Activating Proteins Neurofibromin and p120GAP. J. Mol. Biol. 2003, 329, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, S.; Ramachandran, S.; Cerione, R.A. New Insights into the Role of Conserved, Essential Residues in the GTP Binding/GTP Hydrolytic Cycle of Large G Proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 9219–9226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kötting, C.; Kallenbach, A.; Suveyzdis, Y.; Wittinghofer, A.; Gerwert, K. The GAP Arginine Finger Movement into the Catalytic Site of Ras Increases the Activation Entropy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 6260–6265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gregory, P.E.; Gutmann, D.H.; Mitchell, A.L.; Park, S.; Boguski, M.; Jacks, T.; Wood, D.L.; Jove, R.; Collins, F.S. Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Gene Product (Neurofibromin) Associates with Microtubules. Somat. Cell Mol. Genet. 1993, 19, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, C.; Cheng, Y.; Gutmann, D.A.; Mangoura, D. Differential Localization of the Neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1) Gene Product, Neurofibromin, with the F-Actin or Microtubule Cytoskeleton During Differentiation of Telencephalic Neurons. Dev. Brain Res. 2001, 130, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravind, L.; Neuwald, A.F.; Ponting, C.P. Sec14p- Like Domains in NF1 and dbl-Like Proteins Indicate Lipid Regulation of Ras and Rho Signaling. Curr. Biol. 1999, 9, R195–R197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scheffzek, K.; Welti, S. Pleckstrin Homology (PH) Like Domains—Versatile Modules in Protein-Protein Interaction Platforms. FEBS Lett. 2012, 586, 2662–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Danglot, G.; Régnler, V.; Fauvet, D.; Vassal, G.; Kujas, M.; Bernheim, A. Neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1) mRNAs Expressed in the Central Nervous System Are Differentially Spliced in the 5’ Part of the Gene. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1995, 4, 915–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann, D.; Müller, R.; Kenner, O.; Leistner, W.; Hein, C.; Vogel, W.; Bartelt, B. The N- Terminal Splice Product NF1-10a-2 of the NF1 Gene Codes for a Transmembrane Segment. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 294, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.B.; Ballester, R.; Marchuk, D.A.; Chang, E.; Gutmann, D.H.; Saulino, A.M.; Camonis, J.; Wigler, M.; Collins, F.S. A Conserved Alternative Splice in the Von Recklinghausen Neurofibromatosis (NF1) Gene Produces Two Neurofibromin Isoforms, Both of Which Have GTPase-Activating Protein Activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1993, 13, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gutmann, D.H.; Geist, R.T.; Rose, K.; Wright, U.E. Expression of Two New Protein Isoforms of the Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Gene Product, Neurofibromin, in Muscle Tissues. Dev. Dyn. 1995, 202, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutmann, D.H.; Zhang, Y.; Hirbe, A. Developmental Regulation of a Neuron-Specific Neurofibromatosis 1 Isoform. Ann. Neurol. 1999, 46, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinman, M.N.; Sharma, A.; Luo, G.; Lou, H. Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Alternative Splicing Is a Key Regulator of Ras Signaling in Neurons. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2014, 34, 2188–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferner, R.E.; Gutmann, D.H. Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1). In Neurology of Sexual and Bladder Disorders; Elsevier BV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 115, pp. 939–955. [Google Scholar]

- Ly, K.I.; Blakeley, J.O. The Diagnosis and Management of Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 103, 1035–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pemov, A.; Li, H.; Patidar, R.; Hansen, N.F.; Sindiri, S.; Hartley, S.W.; Wei, J.S.; Elkahloun, A.; Chandrasekharappa, S.C.; Boland, J.F.; et al. The Primacy of NF1 Loss as the Driver of Tumorigenesis in Neurofibromatosis Type 1-Associated Plexiform Neurofibromas. Oncogene 2017, 36, 3168–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutmann, D.H.; Aylsworth, A.; Carey, J.C.; Korf, B.; Marks, J.; Pyeritz, R.E.; Rubenstein, A.; Viskochil, D. The Diagnostic Evaluation and Multidisciplinary Management of Neurofibromatosis 1 and Neurofibromatosis 2. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1997, 278, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korf, B.R. Diagnostic Outcome in Children with Multiple Café Au Lait Spots. Pediatrics 1992, 90, 924–927. [Google Scholar]

- Landau, M.; Krafchik, B.R. The Diagnostic Value of Café-Au-Lait Macules. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1999, 40, 877–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jett, K.; Friedman, J.M. Clinical and Genetic Aspects of Neurofibromatosis. Genet. Med. 2009, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferner, R.E.; Huson, S.M.; Thomas, N.; Moss, C.; Willshaw, H.; Evans, D.G.; Upadhyaya, M.; Towers, R.; Gleeson, M.; Steiger, C.; et al. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Individuals With Neurofibromatosis. J. Med. Genet. 2006, 44, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brosseau, J.-P.; Pichard, D.C.; Legius, E.; Wolkenstein, P.; Lavker, R.M.; Blakeley, J.O.; Riccardi, V.M.; Verma, S.K.; Brownell, I.; Le, L.Q. The Biology of Cutaneous Neurofibromas. Neurology 2018, 91, S14–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ortonne, N.; Wolkenstein, P.; Blakeley, J.O.; Korf, B.; Plotkin, S.R.; Riccardi, V.M.; Miller, D.C.; Huson, S.; Peltonen, J.; Rosenberg, A.; et al. Cutaneous Neurofibromas. Neurology 2018, 91, S5–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Korf, B.R. Plexiform Neurofibromas. Am. J. Med. Genet. Semin. Med. Genet. 1999, 89, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggieri, M.; Huson, S.M. The Clinical and Diagnostic Implications Mosaicism in the Neurofibromatoses. Neurology 2001, 56, 1433–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needle, M.N.; Cnaan, A.; Dattilo, J.; Chatten, J.; Phillips, P.C.; Shochat, S.; Sutton, L.N.; Vaughan, S.N.; Zackai, E.H.; Zhao, H.; et al. Prognostic Signs in the Surgical Management of Plexiform Neurofibroma: The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia experience, 1974-1994. J. Pediatr. 1997, 131, 678–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korf, B.R. Neurofibromatosis. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Elsevier BV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 111, pp. 333–340. [Google Scholar]

- Terracciano, C.; Pachatz, C.; Rastelli, E.; Pastore, F.S.; Melone, M.A.B.; Massa, R. Neurofibromatous Neuropathy: An Ultrastructural Study. Ultrastruct. Pathol. 2018, 42, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, J.M. Neurofibromatosis 1: Clinical Manifestations and Diagnostic Criteria. J. Child Neurol. 2002, 17, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tora, M.S.; Xenos, D.; Texakalidis, P.; Boulis, N.M. Treatment of Neurofibromatosis 1-Associated Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors: A Systematic Review. Neurosurg. Rev. 2019, 43, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beert, E.; Brems, H.; Daniëls, B.; De Wever, I.; Van Calenbergh, F.; Schoenaers, J.; Debiec-Rychter, M.; Gevaert, O.; De Raedt, T.; Bruel, A.V.D.; et al. Atypical Neurofibromas in Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Are Premalignant Tumors. Genes, Chromosom. Cancer 2011, 50, 1021–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miettinen, M.; Antonescu, C.R.; Fletcher, C.D.M.; Kim, A.; Lazar, A.J.; Quezado, M.M.; Reilly, K.M.; Stemmer-Rachamimov, A.; Stewart, D.R.; Viskochil, D.; et al. Histopathologic Evaluation of Atypical Neurofibromatous Tumors and Their Transformation Into Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor in Patients with Neurofibromatosis 1—A Consensus Overview. Hum. Pathol. 2017, 67, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrio, M.; Gel, B.; Terribas, E.; Zucchiatti, A.C.; Moliné, T.; Rosas, I.; Teule, A.; Cajal, S.R.Y.; Lopez-Gutierrez, J.C.; Blanco, I.; et al. Analysis of Intratumor Heterogeneity in Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Plexiform Neurofibromas and Neurofibromas with Atypical Features: Correlating Histological and Genomic Findings. Hum. Mutat. 2018, 39, 1112–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.B.; Largaespada, D.A. New Model Systems and the Development of Targeted Therapies for the Treatment of Neurofibromatosis Type 1-Associated Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors. Genes 2020, 11, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lama, G.; Salsano, M.E.; Grassia, C.; Calabrese, E.; Grassia, M.G.; Bismuto, R.; Melone, M.A.B.; Russo, S.; Scuotto, A. Neurofibromatosis Type 1 and Optic Pathway Glioma. a Long-Term Follow-Up. Minerva Pediatr. 2007, 59, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Listernick, R.; Ferner, R.E.; Liu, G.T.; Gutmann, D.H. Optic Pathway Gliomas in Neurofibromatosis-1: Controversies and Recommendations. Ann. Neurol. 2007, 61, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinori, M.; Hodgson, N.; Zeid, J.L. Ophthalmic Manifestations in Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2018, 63, 518–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campen, C.J.; Gutmann, D.H. Optic Pathway Gliomas in Neurofibromatosis Type 1. J. Child Neurol. 2018, 33, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Listernick, R.; Ferner, R.E.; Piersall, L.; Sharif, S.; Gutmann, D.H.; Charrow, J. Late- Onset Optic Pathway Tumors in Children with Neurofibromatosis 1. Neurology 2004, 63, 1944–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eoli, M.; Saletti, V.; Finocchiaro, G. Neurological Malignancies in Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2019, 31, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiller, C.A.; Chessells, J.M.; Fitchett, M. Neurofibromatosis and Childhood Leukaemia/LymphomA: A Population-Based UKCCSG Study. Br. J. Cancer 1994, 70, 969–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walther, M.M.; Herring, J.; Enquist, E.; Keiser, H.R.; Linehan, W.M. Von Recklinghausen′s Disease and Pheochromocytomas. J. Urol. 1999, 162, 1582–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miettinen, M.; Fetsch, J.F.; Sobin, L.H.; Lasota, J. Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors in Patients with Neurofibromatosis. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2006, 30, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, L.; Anderson, J.R.; Arndt, C.; Raney, R.; Meyer, W.H.; Pappo, A.S. Neurofibromatosis in Children with RhabdomyosarcomA: A Report from the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study IV. J. Pediatr. 2004, 144, 666–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D.R.; Sloan, J.L.; Yao, L.; Mannes, A.J.; Moshyedi, A.; Lee, C.-C.R.; Sciot, R.; De Smet, L.; Mautner, V.-F.; Legius, E. Diagnosis, Management, and Complications of Glomus Tumours of the Digits in Neurofibromatosis Type 1. J. Med. Genet. 2010, 47, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktenli, C.; Gül, D.; Deveci, M.S.; Saglam, M.; Upadhyaya, M.; Thompson, P.; Consoli, C.; Kocar, I.H.; Pilarski, R.; Zhou, X.-P.; et al. Unusual Features in a Patient with Neurofibromatosis Type 1: Multiple Subcutaneous Lipomas, a Juvenile Polyp in Ascending Colon, Congenital Intrahepatic Portosystemic Venous Shunt, and Horseshoe Kidney. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2004, 127, 298–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bollag, G.; Clark, R.; Stevens, J.; Conroy, L.; Fults, D.; Ward, K.; Friedman, E.; Samowitz, W.; Robertson, M.; et al. Somatic Mutations in the Neurofibromatosis 1 Gene in Human Tumors. Cell 1992, 69, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, E.; Puig, S.; Otero, D.; Gaona, A.; Kruyer, H.; Ars, E.; Estivill, X.; Lazaro, C. Confirmation of a Double-Hit Model for the NF1 Gene in Benign Neurofibromas. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997, 61, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Upadhyaya, M.; Kluwe, L.; Spurlock, G.; Monem, B.; Majounie, E.; Mantripragada, K.; Ruggieri, M.; Chuzhanova, N.; Evans, D.; Ferner, R.; et al. Germline and Somatic NF1 Gene Mutation Spectrum in NF1-Associated Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors (MPNSTs). Hum. Mutat. 2007, 29, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petramala, L.; Giustini, S.; Zinnamosca, L.; Marinelli, C.; Colangelo, L.; Cilenti, G.; Formicuccia, M.C.; D’Erasmo, E.; Calvieri, S.; Letizia, C. Bone Mineral Metabolism in Patients with Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (Von Recklingausen Disease). Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2011, 304, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alwan, S.; Armstrong, L.; Joe, H.; Birch, P.; Szudek, J.; Friedman, J.M. Associations of Osseous Abnormalities in Neurofibromatosis 1. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2007, 143, 1326–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szudek, J.; Birch, P.; Friedman, J.M.; Participants, T.N. Growth in North American White Children with Neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1). J. Med. Genet. 2000, 37, 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Illés, T.; Halmai, V.; De Jonge, T.; Dubousset, J. Decreased Bone Mineral Density in Neurofibromatosis-1 Patients with Spinal Deformities. Osteoporos. Int. 2001, 12, 823–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuorilehto, T.; Pöyhönen, M.H.; Bloigu, R.; Heikkinen, J.; Väänänen, K.; Peltonen, J. Decreased Bone Mineral Density and Content in Neurofibromatosis Type 1: Lowest Local Values Are Located in the Load-Carrying Parts of the Body. Osteoporos. Int. 2004, 16, 928–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammert, M.; Kappler, M.; Mautner, V.-F.; Lammert, K.; Störkel, S.; Friedman, J.M.; Atkins, D. Decreased Bone Mineral Density in Patients with Neurofibromatosis 1. Osteoporos. Int. 2005, 16, 1161–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, K.; Ozmen, M.; Goksan, S.B.; Eskiyurt, N. Bone Mineral Density in Children with Neurofibromatosis 1. Acta Paediatr. 2007, 96, 1220–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, D.A.; Moyer-Mileur, L.J.; Murray, M.; Slater, H.; Sheng, X.; Carey, J.C.; Dube, B.; Viskochil, D.H. Bone Mineral Density in Children and Adolescents with Neurofibromatosis Type 1. J. Pediatr. 2007, 150, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dulai, S.; Briody, J.; Schindeler, A.; North, K.N.; Cowell, C.T.; Little, D.G. Decreased Bone Mineral Density in Neurofibromatosis Type 1: Results from a Pediatric Cohort. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2007, 27, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindeler, A.; Little, D.G. Recent Insights Into Bone Development, Homeostasis, and Repair in Type 1 Neurofibromatosis (NF1). Bone 2008, 42, 616–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]