The Pre-Operative GRADE Score Is Associated with 5-Year Survival among Older Patients with Cancer Undergoing Surgery

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Pre-Operative Assessment

2.3. Post-Operative Outcomes

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patients

3.2. Baseline Characteristics of Patients

3.3. 30-Day Post-Operative Complications

3.4. Preoperative Factors Associated with 5-Year Post-Operative Mortality

3.5. Improvement of the GRADE Score: The GRADE-Surgery Score

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| GRADE | GRADE-Surgery |

|---|---|

| Weight loss ≥ 5% | GRADE > 8 |

| No = 0 | No = 0 |

| Yes = 1 | Yes = 3 |

| Gait speed < 0.8 m/s | IADL ≤ ¾ * |

| No = 0 | No = 0 |

| Yes = 3 | Yes = 4 |

| Cancer site | |

| Colorectal = 3 | |

| Non-breast gynaecological = 3 | |

| Digestive non-colorectal = 4 | |

| Cancer extension | |

| Local = 0 | |

| Locally-advanced = 3 | |

| Metastatic = 5 | |

| Total = 3–13 | Total = 0–7 |

| C-index (threshold of 8) = 0.76 | C-index (threshold of 4) = 0.81 |

| Scoring Systems | Study Population | Variables | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PREOP [30] | 229 patients ≥ 70 years Cancer surgery: breast, colorectal, gastric, gynaecologic, pancreas and bile-duct, renal and bladder, soft tissue and skin | Total = 5 Sex, type of surgery, TGUG, ASA scale, NRS | Associated with 5-year overall survival Good discrimination (C-index = 0.78) | No external validation Time to scoring with NRS tool |

| VESPA [32] | 476 patients ≥ 70 years Cancer-surgery: Dermatologic, gastrointestinal, urologic, breast, head and neck, ophtalmologic | Total = 6 ADL/IADL, self-report inability to manage oneself, sex, Charlson’s comorbidity index, complexity of surgery procedure | Associated with 30-day post-operative complications Very-good discrimination for geriatric complications (C-index = 0.83) Good discrimination for surgical complications (C-index = 0.70) Good discrimination for post-discharge needs (C-index = 0.77) The largest sample | No external validation Association with overall survival not reported Time to scoring with several scales |

| GA-GYN [33] | 189 patients ≥ 70 years Cancer-surgery: Non-breast gynaecological | Total = 8 Need for assistance in taking medications, limited in walking one block, decreased social activity, number of falls, fair or worse hearing, age, hemoglobin, creatinine | Associated with 6-week post-operative complications (stage III/IV only) Specific to gynaecological cancers | No external validation Not associated with overall survival Time to scoring with biological variables Discrimination lacking |

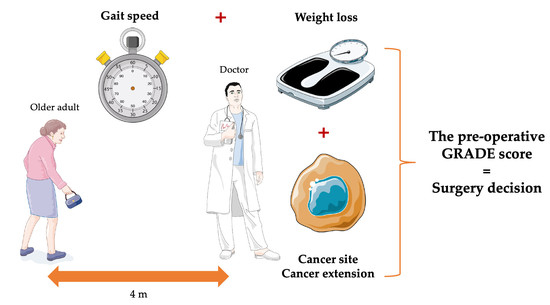

| GRADE [14] | 136 patients ≥ 65 years Cancer-surgery: colorectal, oesophagus, gastric, pancreas and bile-duct, anus, gastro-intestinal and stromal tumours, ovarian, uterus | Total = 4 Weight loss, Gait speed, Cancer site, Cancer extension | Associated with 5-year overall survival Good discrimination (C-index = 0.76) Univariate association with 30-day post-operative complications The simplest score Usefulness when a geriatric assessment is not available | No external validation The smallest sample |

References

- Pilleron, S.; Sarfati, D.; Janssen-Heijnen, M.; Vignat, J.; Ferlay, J.; Bray, F.; Soerjomataram, I. Global cancer incidence in older adults, 2012 and 2035: A population-based study. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 144, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papamichael, D.; Audisio, R.A.; Glimelius, B.; de Gramont, A.; Glynne-Jones, R.; Haller, D.; Kohne, C.-H.; Rostoft, S.; Lemmens, V.; Mitry, E.; et al. Treatment of colorectal cancer in older patients: International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) consensus recommendations 2013. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Audisio, R.A. Preoperative evaluation of the older patient with cancer. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2016, 7, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canouï-Poitrine, F.; Lièvre, A.; Dayde, F.; Lopez-Trabada-Ataz, D.; Baumgaertner, I.; Dubreuil, O.; Brunetti, F.; Coriat, R.; Maley, K.; Pernot, S.; et al. Inclusion of Older Patients with Cancer in Clinical Trials: The SAGE Prospective Multicenter Cohort Survey. Oncologist 2019, 24, e1351–e1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lewis, J.H.; Kilgore, M.L.; Goldman, D.P.; Trimble, E.L.; Kaplan, R.; Montello, M.J.; Housman, M.G.; Escarce, J.J. Participation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer clinical trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 1383–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristjansson, S.R.; Farinella, E.; Gaskell, S.; Audisio, R.A. Surgical risk and post-operative complications in older unfit cancer patients. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2009, 35, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamidanna, R.; Almoudaris, A.M.; Faiz, O. Is 30-day mortality an appropriate measure of risk in elderly patients undergoing elective colorectal resection? Colorectal Dis. 2012, 14, 1175–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannotti, C.; Sambuceti, S.; Signori, A.; Ballestrero, A.; Murialdo, R.; Romairone, E.; Scabini, S.; Caffa, I.; Odetti, P.; Nencioni, A.; et al. Frailty assessment in elective gastrointestinal oncogeriatric surgery: Predictors of one-year mortality and functional status. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2019, 10, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaglia, A.; Tavilla, A.; Shack, L.; Brenner, H.; Janssen-Heijnen, M.; Allemani, C.; Colonna, M.; Grande, E.; Grosclaude, P.; Vercelli, M. The cancer survival gap between elderly and middle-aged patients in Europe is widening. Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 1006–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huisman, M.G.; Kok, M.; de Bock, G.H.; van Leeuwen, B.L. Delivering tailored surgery to older cancer patients: Preoperative geriatric assessment domains and screening tools—A systematic review of systematic reviews. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 2017, 43, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamoukdjian, F.; Liuu, E.; Caillet, P.; Herbaud, S.; Gisselbrecht, M.; Poisson, J.; Boudou-Rouquette, P.; Zelek, L.; Paillaud, E. How to Optimize Cancer Treatment in Older Patients: An Overview of Available Geriatric Tools. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 42, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montroni, I.; Ugolini, G.; Saur, N.M.; Spinelli, A.; Rostoft, S.; Millan, M.; Wolthuis, A.; Daniels, I.R.; Hompes, R.; Penna, M.; et al. Personalized management of elderly patients with rectal cancer: Expert recommendations of the European Society of Surgical Oncology, European Society of Coloproctology, International Society of Geriatric Oncology, and American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 44, 1685–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collard, M.K.; Moszkowicz, D.; Clause-Verdreau, A.-C.; Beauchet, A.; Cudennec, T.; Vychnevskaia, K.; Malafosse, R.; Peschaud, F. Postoperative morbidity and mortality for malignant colon obstruction: The American College of Surgeon calculator reliability. J. Surg. Res. 2018, 226, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angeli, E.; Chouahnia, K.; Canoui-Poitrine, F.; Duchemann, B.; Aparicio, T.; Paillaud, E.; Zelek, L.; Bousquet, G.; Pamoukdjian, F. Development, Validation and Clinical Impact of a Prediction Model for 6-Month Mortality in Older Cancer Patients: The GRADE. Aging (Albany N.Y.) 2020, 12, 4230–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamoukdjian, F.; Aparicio, T.; Zebachi, S.; Zelek, L.; Paillaud, E.; Canoui-Poitrine, F. Comparison of mobility indices for predicting early death in older patients with cancer: The PF-EC cohort study. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2019, 75, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soubeyran, P.; Bellera, C.; Goyard, J.; Heitz, D.; Curé, H.; Rousselot, H.; Albrand, G.; Servent, V.; Jean, O.S.; van Praagh, I.; et al. Screening for Vulnerability in Older Cancer Patients: The ONCODAGE Prospective Multicenter Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e115060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.D.; Paradis, C.F.; Houck, P.R.; Mazumdar, S.; Stack, J.A.; Rifai, A.H.; Mulsant, B.; Reynolds, C.F. Rating chronic medical illness burden in geropsychiatric practice and research: Application of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. Psychiatry Res. 1992, 41, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnjidic, D.; Hilmer, S.N.; Blyth, F.M.; Naganathan, V.; Waite, L.; Seibel, M.J.; McLachlan, A.J.; Cumming, R.G.; Handelsman, D.J.; Le Couteur, D.G. Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: Five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2012, 65, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, S.; Downs, T.D.; Cash, H.R.; Grotz, R.C. Progress in development of the index of ADL. Gerontologist 1970, 10, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawton, M.P.; Brody, E.M. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969, 9, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raynaud-Simon, A.; Revel-Delhom, C.; Hébuterne, X.; French Nutrition and Health Program; French Health High Authority. Clinical practice guidelines from the French Health High Authority: Nutritional support strategy in protein-energy malnutrition in the elderly. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 30, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clément, J.P.; Nassif, R.F.; Léger, J.M.; Marchan, F. Development and contribution to the validation of a brief French version of the Yesavage Geriatric Depression Scale. Encephale 1997, 23, 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-mental state”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindo, D.; Demartines, N.; Clavien, P.-A. Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann. Surg. 2004, 240, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, H.B.; Mehta, V.; Girman, C.J.; Adhikari, D.; Johnson, M.L. Regression coefficient–based scoring system should be used to assign weights to the risk index. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 79, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ghignone, F.; van Leeuwen, B.L.; Montroni, I.; Huisman, M.G.; Somasundar, P.; Cheung, K.L.; Audisio, R.A.; Ugolini, G. The assessment and management of older cancer patients: A SIOG surgical task force survey on surgeons’ attitudes. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 2016, 42, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novello, M.; Mandarino, F.V.; Di Saverio, S.; Gori, D.; Lugaresi, M.; Duchi, A.; Argento, F.; Cavallari, G.; Wheeler, J.; Nardo, B. Post-operative outcomes and predictors of mortality after colorectal cancer surgery in the very elderly patients. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kenig, J.; Szabat, K.; Mituś, J.; Mituś-Kenig, M.; Krzeszowiak, J. Usefulness of eight screening tools for predicting frailty and postoperative short- and long-term outcomes among older patients with cancer who qualify for abdominal surgery. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 46, 2091–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugolini, G.; Pasini, F.; Ghignone, F.; Zattoni, D.; Bacchi Reggiani, M.L.; Parlanti, D.; Montroni, I. How to select elderly colorectal cancer patients for surgery: A pilot study in an Italian academic medical center. Cancer Biol. Med. 2015, 12, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisman, M.G.; Ghignone, F.; Ugolini, G.; Sidorenkov, G.; Montroni, I.; Vigano, A.; Carino, N.D.L.; Farinella, E.; Cirocchi, R.; Audisio, R.A.; et al. Long-Term Survival and Risk of Institutionalization in Onco-Geriatric Surgical Patients: Long-Term Results of the PREOP Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 1235–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquina, C.T.; Mohile, S.G.; Tejani, M.A.; Becerra, A.Z.; Xu, Z.; Hensley, B.J.; Arsalani-Zadeh, R.; Boscoe, F.P.; Schymura, M.J.; Noyes, K.; et al. The impact of age on complications, survival, and cause of death following colon cancer surgery. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 116, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pollock, Y.; Chan, C.-L.; Hall, K.; Englesbe, M.; Diehl, K.M.; Min, L. A Novel Geriatric Assessment Tool that Predicts Postoperative Complications in Older Adults with Cancer. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2020, 11, 866–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Deng, W.; Tew, W.; Bender, D.; Mannel, R.S.; Littell, R.D.; DeNittis, A.S.; Edelson, M.; Morgan, M.; Carlson, J.; et al. Pre-Operative Assessment and Post-Operative Outcomes of Elderly Women with Gynecologic Cancers, Primary Analysis of NRG CC-002: An NRG Oncology Group/Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 150, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, S.L.; Lee, M.J.; George, J.; Kerr, K.; Moug, S.; Wilson, T.R.; Brown, S.R.; Wyld, L. Prehabilitation in elective abdominal cancer surgery in older patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BJS Open 2020, 4, 1022–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Whole Cohort | GRADE ≤ 8 | GRADE > 8 | p * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Risk | High-Risk | |||

| n = 136 (%) | n = 68 (%) | n = 68 (%) | ||

| Age, y | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 80 ± 7 | 78 ± 7 | 82 ± 7 | 0.0008 |

| 65–74 | 32 (23.5) | 20 (29) | 12 (18) | 0.09 |

| 75–84 | 66 (48.5) | 34 (50) | 32 (47) | |

| ≥85 | 38 (28) | 14 (21) | 24 (35) | |

| Gender (male) | 71 (52) | 42 (62) | 29 (43) | 0.02 |

| Outpatient (yes) | 108 (79) | 60 (88) | 48 (70) | 0.25 |

| Cancer site: | 0.25 | |||

| Colorectal | 99 (73) | 47 (69) | 52 (76) | |

| Others † | 37 (27) | 21 (31) | 16 (24) | |

| Local and locally-advanced cancer (yes) | 107 (79) | 62 (91) | 45 (66) | <0.0001 |

| ASA scale > 2 | 60 (44) | 21 (31) | 39 (57) | 0.001 |

| ECOG > 2 | 38 (28) | 9 (13) | 29 (43) | 0.0001 |

| G8-index £ 14/17 (n = 133) | 112 (84) | 50 (73) | 62 (91) | 0.007 |

| Comorbidities: | ||||

| CIRSG total ≥ 14 | 67 (49) | 29 (43) | 38 (56) | 0.12 |

| Polypharmacy (yes) | 88 (65) | 42 (62) | 46 (68) | 0.47 |

| Dependency | ||||

| ADL £ 5/6 | 45 (33) | 12 (18) | 33 (48) | 0.0001 |

| IADL £ 3/4 | 76 (56) | 26 (38) | 50 (73) | <0.0001 |

| Malnutrition | ||||

| BMI < 21 kg/m2 (n = 134) | 18 (13) | 8 (12) | 10 (15) | 0.56 |

| Depressed mood | ||||

| Mini-GDS ≥ 1/4 | 51 (37.5) | 22 (32) | 29 (43) | 0.21 |

| Cognition (n = 91) | ||||

| MMSE < 24/30 | 41 (45) | 19 (28) | 22 (32) | 0.03 |

| 30-day post-operative complications | ||||

| Clavien-Dindo ≥ 1 | 91 (67) | 41 (60) | 50 (73) | 0.1 |

| Clavien-Dindo ≥ 3a (severe) | 50 (37) | 19 (28) | 31 (46) | 0.03 |

| Variables | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | (95% CI) | p * | aHR | (95% CI) | p * | |

| Age (per 1 SD of more) | 1.05 | 1.01–1.10 | 0.02 | - | ||

| Gender (male) | 0.61 | 0.34–1.09 | 0.09 | - | ||

| Outpatients (yes) | 0.55 | 0.29–1.06 | 0.07 | - | ||

| GRADE score | 0.0001 | |||||

| ≤8 (low risk) | 1 (reference) | – | 1 (reference) | - | 0.005 | |

| >8 (high risk) | 3.47 | 1.85–6.54 | 2.64 | (1.34–5.21) | ||

| ASA scale > 2 | 3.43 | 1.87–6.30 | <0.0001 | - | ||

| ECOG-PS > 2 | 3.42 | 1.88–6.23 | <0.0001 | - | ||

| G8-index £ 14/17 (n = 133) | 3.09 | 0.96–10.0 | 0.05 | - | ||

| Comorbidities: | ||||||

| CIRSG total ≥ 14 | 1.95 | 1.09–3.51 | 0.02 | - | ||

| Polypharmacy (yes) | 1.63 | 0.86–3.10 | 0.13 | - | ||

| Dependency | ||||||

| ADL £ 5/6 | 2.22 | 1.24–3.98 | 0.007 | - | ||

| IADL £ 3/4 | 4.32 | 2.13–8.73 | <0.0001 | 2.95 | (1.40–6.23) | 0.004 |

| Malnutrition | ||||||

| BMI < 21 kg/m2 (n = 134) | 2.66 | 1.35–5.25 | 0.004 | 2.97 | (1.49–5.93) | 0.002 |

| Depressed mood | ||||||

| Mini-GDS ≥ 1/4 | 1.88 | 1.06–3.33 | 0.03 | - | ||

| Cognition (n = 91) | ||||||

| MMSE < 24/30 | 2.61 | 1.18–5.73 | 0.01 | - | ||

| Risk of Death | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRADE | Median Survival (Months) | 12 m | 24 m | 36 m | 50 m | 62 m |

| ≤8 (low risk) | NR | 8% | 13% | 22% | 29% | 29% |

| >8 (high risk) | 34.2 (19.2–50.1) | 31% | 37% | 55% | 62% | 74% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wind, P.; ap Thomas, Z.; Laurent, M.; Aparicio, T.; Siebert, M.; Audureau, E.; Paillaud, E.; Bousquet, G.; Pamoukdjian, F. The Pre-Operative GRADE Score Is Associated with 5-Year Survival among Older Patients with Cancer Undergoing Surgery. Cancers 2022, 14, 117. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/cancers14010117

Wind P, ap Thomas Z, Laurent M, Aparicio T, Siebert M, Audureau E, Paillaud E, Bousquet G, Pamoukdjian F. The Pre-Operative GRADE Score Is Associated with 5-Year Survival among Older Patients with Cancer Undergoing Surgery. Cancers. 2022; 14(1):117. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/cancers14010117

Chicago/Turabian StyleWind, Philippe, Zoe ap Thomas, Marie Laurent, Thomas Aparicio, Matthieu Siebert, Etienne Audureau, Elena Paillaud, Guilhem Bousquet, and Frédéric Pamoukdjian. 2022. "The Pre-Operative GRADE Score Is Associated with 5-Year Survival among Older Patients with Cancer Undergoing Surgery" Cancers 14, no. 1: 117. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/cancers14010117