On Manuscripts, Prints and Blessed Transformations: Caterina da Siena’s Legenda maior as a Model of Sainthood in Premodern Castile

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Ludolphus de Saxonia. Vita Christi cartuxano romançado por fray Ambrosio [Montesino]. Alcalá de Henares, 1502–1503;

- San Juan Clímaco. Sant Juan Clímaco que trata de las tablas et escalera spiritual: por donde han de subir al estado de la perfecion. Toledo, 1504;

- Sancti Joannis Climaci. Scala spiritualis. Toledo, 1505;

- Angela de Fulginio [Angela of Foligno], Liber qui dicitur Angela de Fulginio. Toledo, 1505 (also includes Mechthild von Hackeborn’s Liber spiritualis gratiae and the First rule of Francesco d’Assisi);

- Angela de Fulgino [Angela of Foligno], Libro de la bienaventurada sancta Angela de Fulgino. Toledo: 1510 (also includes First Rule by Chiara d’Assisi and some chapters of the Tratado de la vida e instrución espiritual by Vicente Ferrer);

- Raymundo de Capua. La vida de la bienaventurada sancta Caterina de Sena trasladada de latín en castellano por el reverendo maestro fray Antonio de la Peña de la orden de los predicadores. Y la vida de la bienaventurada soror Juana de Orbieto, y de soror Margarita de Castello, trans. Antonio de la Peña. Alcalá, 1511;

- Sancta Catherina de Sena, Obra de las epístolas y oraciones de la bienaventurada virgen Sancta Catherina de Sena de la orden de los predicadores. Las cuales fueron traducidas del toscano en nuestra lengua castellana por mandado del muy Ilustre y Reverendísimo señor el Cardenal de España, Arzobispo de la Santa Iglesia de Toledo, etc. Alcalá de Henares, 1512.

2. The Cisnerian Base Manuscript

2.1. The Contents of the 1511 Edition

2.2. The Epistle

2.3. Caterina’s Campaign of Canonization

2.4. The Lives of Vanna and Margherita

2.5. Partial Conclusions

3. The Cisnerian Base Manuscript II: The Legenda maior Text

4. Illiterate Prophetism, the Stigmata and Courtly Politics

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acosta-García, Pablo. Forthcoming a. Women Prophets for a New World: Angela of Foligno, “Living Saints”, and the Reform Movement in Cardinal Cisneros’ Castile. In Exemplarity and Gender in Medieval and Early Modern Iberia. Edited by Maria Morrás, Rebeca Sanmartín and YonSoo Kim. Leiden: Brill.

- Acosta-García, Pablo. Forthcoming b. Marked Holy Women: Exemplary Reading Itineraries in the Works of Low Medieval Women Mystics Printed by Cisneros. In Hispania Sacra. Madrid: CSIC Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas.

- Bara Bancel, Silvia. 2014. La Escuela Mística Renana y Las Moradas de Santa Teresa. In Las Moradas del Castillo Interior de Santa Teresa de Jesús: Actas del IV Congreso Internacional Teresiano en Preparación del V Centenario de su Nacimiento (1515–2015). Edited by Francisco Javier Sancho Fermín and Rómulo H. Cuartas Londroño. Burgos: Monte Carmelo, pp. 179–219. [Google Scholar]

- Bartolomei Romagnoli, Alessandra. 2013. La disputa sulle stimmate. In ‘Virgo Digna Coelo’. Caterina e la sua Eredità. Edited by Alessandra Bartolomei Romagnoli, Luciano Cinelli and Pierantonio Piatti. Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, pp. 407–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bataillon, Marcel. 1996. Erasmo y España. Mexico: FCE. First published 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Beattie, Blake. 2012. Catherine of Siena and the Papacy. In A Companion to Catherine of Siena. Edited by Carolyn Muessig, George Ferzoco and Beverly Mayne Kienzle. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 73–98. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán de Heredia, Vicente. 1939. Historia de la Reforma de la Provincia de España (1450–1550). Roma: Instituto Storico Domenicano. [Google Scholar]

- Bilinkoff, Jodi. 1992. A Spanish Prophetess and Her Patrons: The Case of María de Santo Domingo. Sixteenth Century Journal 23: 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffarini, Tommaso. 1974. Libellus de Supplemento Legende Prolixe Virginis Beate Catherine de Senis. Edited by Iuliana Cavallini and Imelda Foralosso. Roma: Edizione Cateriniane, Available online: http://www.centrostudicateriniani.it/images/documenti/libellus-de-supplemento/libellus-de-supplemento.html (accessed on 6 September 2019).

- Casas Nadal, Montserrat. 2007. Les versions catalanes de la Vida de santa Caterina de Siena. Notes sobre el text i el paratex. Quaderns d’Italià 12: 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Catalina García, Juan. 1889. Ensayo de una Tipografía Complutense. Madrid: Imprenta y Fundición de Manuel Tello. [Google Scholar]

- Cirlot, Victoria, and Blanca Garí. 2008. La Mirada Interior. Madrid: Siruela. [Google Scholar]

- Da Capua, Raymundo. 1511. La vida de la Bienaventurada Sancta Caterina de Sena Trasladada de latín en Castellano por el Reverendo Maestro Fray Antonio de la Peña de la Orden de los Predicadores. Y la vida de la Bienaventurada soror Juana de Orbieto, y de soror Margarita de Castello. Translated by Antonio de la Peña. Alcalá: Arnao Guillen de Brocar. [Google Scholar]

- De Aranda Quintanilla y Mendoza, Pedro. 1653. Archetypo de Virtudes, Espexo de Prelados, el Venerable Padre y Siervo de Dios, Fray Francisco Ximénez de Cisneros. Palermo: Nicolás Bua. [Google Scholar]

- de Jesús, Teresa. 2014. Libro de la vida. Edited by Fidel Sebastián Mediavilla. Madrid: RAE. [Google Scholar]

- Ferzoco, George. 2012. The Processo Castellano and the Canonization of Catherine of Siena. In A Companion to Catherine of Siena. Edited by Carolyn Muessig, George Ferzoco and Beverly Mayne Kienzle. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 185–202. [Google Scholar]

- Ganz, David. 2013. The Dilemma of a Saint’s Portrait: Catherine’s Stigmata between Invisible Body and Visible Pictorial Sign. In Catherine of Siena: The Creation of a Cult. Edited by Jeffrey F. Hamburger and Gabriela Signori. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 239–62. [Google Scholar]

- García Oro, José. 1971. Cisneros y la Reforma del Clero Español en Tiempo de los Reyes Católicos. Madrid: CSIC. [Google Scholar]

- García Oro, José, and Segundo L. Pérez López. 2012. La reforma religiosa durante la gobernación del cardenal Cisneros (1516–1518): Hacia la consolidación de un largo proceso. Annuarium Sancti Iacobi 1: 47–174. [Google Scholar]

- Giunta, Diega. 2012. The Iconography of Catherine of Siena’s Stigmata. In A Companion to Catherine of Siena. Edited by Carolyn Muessig, George Ferzoco and Beverly Mayne Kienzle. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 259–94. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez de Castro, Alvar. 1569. De Rebus Gestis a Francisco Ximenio Cisnerio, Archiepiscopo Toletano, Libri Octo. Alcalá: Andrés Angulo. [Google Scholar]

- Graña, María del Mar. 2014. ¿Una memoria femenina de escritura espiritual? La recepción de las místicas medievales en el convento de Santa María de la Cruz de Cubas. In Letras en la Celda. Cultura Escrita de los Conventos Femeninos en la España Moderna. Edited by Nieves Baranda Leturio and María Carmen Marín Pina. Madrid: Iberoamericana Vervuert, pp. 189–206. [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger, Jeffrey F. 2002. St. John the Divine. The Deified Evangelist in Medieval Art and Theology. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger, Jeffrey F., and Gabriela Signori. 2013. The Making of a Saint: Catherine of Siena, Tommaso Caffarini, and the Others. In Catherine of Siena: The Creation of a Cult. Edited by Jeffrey F. Hamburger and Gabriela Signori. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Herrán Martínez de San Vicente, Ainara. 2011. El Mecenazgo Literario de las Jerarquías Eclesiásticas en la Época de los Reyes Católicos. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, Elizabeth Theresa. 2002. Cisneros and the Translation of Women’s Spirituality. In The Vernacular Spirit: Essays on Medieval Religious Literature. Edited by Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski, Duncan Robertson and Nancy Bradley Warren. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, pp. 283–95. [Google Scholar]

- Huerga, Álvaro. 1968. Santa Catalina de Siena en la historia de la espiritualidad hispana. Teología Espiritual 12: 165–228. [Google Scholar]

- Krafft, Otfried. 2013. Many Strategies and One Goal: The Difficult Road to the Canonization of Catherine of Siena. In Catherine of Siena: The Creation of a Cult. Edited by Jeffrey F. Hamburger and Gabriela Signori. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Laurent, Marie-Hyacinthe. 1942. Il Processo Castellano con Appendice di Documenti sul Culto e la Canonizzazione di S. Caterina. Milan: Fratelli Bocca. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmijoki-Gardner, Maiju. 2004. Writing Religious Rules as an Interactive Process: Dominican Penitent Women and the Making of Their Regula. Speculum 79: 660–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmijoki-Gardner, Maiju. 2012. Denial as Action—Penance and its Place in the Life of Catherine of Siena. In A Companion to Catherine of Siena. Edited by Carolyn Muessig, George Ferzoco and Beverly Mayne Kienzle. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 113–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lungarotti, Maria Cristina. 1994. Le Legendae de Margherita da Città di Castello. Spoleto: Centro italiano di Studi Sull’alto medioevo. [Google Scholar]

- Luongo, F. Thomas. 2006. The Saintly Politics of Catherine of Siena. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luongo, F. Thomas. 2013. Saintly Authorship in the Italian Renaissance: The Quattrocento Reception of Catherine of Siena’s Letters. In Catherine of Siena: The Creation of a Cult. Edited by Jeffrey F. Hamburger and Gabriela Signori. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 135–68. [Google Scholar]

- Martín Abad, Julián. 1991. La Imprenta en Alcalá de Henares (1502–1600). Madrid: Arco/Libros, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- McGinn, Bernard. 2017. Mysticism in the Golden Age of Spain (1500–1650). Part 2. New York: Crossroad Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, Catherine M. 2013. Wondrous Words: Catherine of Siena’s Miracolous Reading and Writing According to the Early Sources. In Catherine of Siena: The Creation of a Cult. Edited by Jeffrey F. Hamburger and Gabriela Signori. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 263–90. [Google Scholar]

- Nocentini, Silvia. 2005. Lo “scriptorium” di Tommaso Caffarini a Venezia. Hagiographica 12: 79–146. [Google Scholar]

- Nocentini, Silvia. 2013a. Prolegomena. In Raimondo da Capua, Legenda Maior. Edited by Silvia Nocentini. Firenze: SISMEL—Edizioni del Galluzzo. [Google Scholar]

- Nocentini, Silvia. 2013b. “Pro solatio illicteratorum”: The Earliest Italian Translations of the Legenda Maior. In Catherine of Siena: The Creation of a Cult. Edited by Jeffrey F. Hamburger and Gabriela Signori. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 135–68. [Google Scholar]

- Paoli, Emore, and Luigi G. G. Ricci. 1996. La Legenda di Vanna da Orvieto. Spoleto: Centro italiano di Studi Sull’alto medioevo. [Google Scholar]

- Sainz Rodríguez, Pedro. 1979. La Siembra Mística del Cardenal Cisneros y las Reformas en la Iglesia. Madrid: Fundación Universitaria Española. [Google Scholar]

- Sanmartín Bastida, Rebeca. 2012. La Representación de las Místicas. Sor María de Santo Domingo en su Contexto Europeo. Santander: Propileo. [Google Scholar]

- Sanmartín Bastida, Rebeca. 2013a. Santa Teresa y la herencia de las visionarias del medievo: De las monjas de Helfta a María de Santo Domingo. Analecta Malacitana 36: 275–86. [Google Scholar]

- Sanmartín Bastida, Rebeca. 2013b. La construcción de la santidad en María de Santo Domingo: La imitación de Catalina de Siena. Ciencia Tomista 140: 141–59. [Google Scholar]

- Sanmartín Bastida, Rebeca. 2017. Castilian Visionary Women, Books and Readings before St. Teresa of Ávila. JSL 21: 30–49. [Google Scholar]

- Sanmartín Bastida, Rebeca. forthcoming. La emergencia de la autoridad femenina “ortodoxa”: El modelo de María de Ajofrín. In Hispania Sacra. Madrid: CSIC Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas.

- Sastre Varas, Lázaro. 1990. Proceso a la Beata de Piedrahíta. Archivo Dominicano 11: 359–402. [Google Scholar]

- Sastre Varas, Lázaro. 1991. Proceso a la Beata de Piedrahíta (II). Archivo Dominicano 12: 337–86. [Google Scholar]

- Sastre Varas, Lázaro. 2004. Fray Jerónimo de Ferrara y el círculo de la Beata de Piedrahíta. In La figura de Jerónimo Savonarola y su Influencia en España y Europa. Edited by Donald Weinstein, Júlia Benavent and Inés Rodríguez. Firenze: SISMEL—Edizioni del Galluzzo, pp. 169–75. [Google Scholar]

- Schultze, Dirk. 2013. Translating St Catherine of Siena in Fifteenth-Century England. In Catherine of Siena: The Creation of a Cult. Edited by Jeffrey F. Hamburger and Gabriela Signori. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 185–214. [Google Scholar]

- Société des Bollandistes. 1643. Acta Sanctorum, 3rd ed. Bruxelles and Antwerp: Société des Bollandistes, Aprilis 3, pp. 969–70. [Google Scholar]

- Surtz, Ronald E. 1995. Writing Women in Late Medieval and Early Modern Spain: The Mothers of Saint Teresa of Avila. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tylus, Jane. 2012. Mystical Literacy: Writing and Religious Women in Late Medieval Italy. In A Companion to Catherine of Siena. Edited by Carolyn Muessig, George Ferzoco and Beverly Mayne Kienzle. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 155–84. [Google Scholar]

- Tylus, Jane. 2013. Writing versus Voice: Tommaso Caffarini and the Production of a Literate Catherine. In Catherine of Siena: The Creation of a Cult. Edited by Jeffrey F. Hamburger and Gabriela Signori. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 291–314. [Google Scholar]

- Vauchez, André. 2017. Catalina de Siena. Vida y Pasiones. Barcelona: Herder. First published 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zarri, Gabriela. 1980. Le sante vive. Per una tipologia della santità femminile nel primo Cinquecento. Annali Dell’istituto Storico Italo-Germanico in Trento 6: 371–445. [Google Scholar]

- Zarri, Gabriela. 1990. Le Sante vive. Cultura e Religiosità Femminile Nella Prima età Moderna. Torino: Rosenberg & Sellier. Torino: Rosenberg & Sellier. [Google Scholar]

- Zarri, Gabriela. 2013. Catherine of Siena and the Italian Public. In Catherine of Siena: The Creation of a Cult. Edited by Jeffrey F. Hamburger and Gabriela Signori. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 69–82. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | About the short version (reducta), the Legenda minor, see (Nocentini 2013a, p. 30; 2013b, p. 175). The mantellate were the original group of penitent women very closely associated with the Dominican Order. |

| 2 | I will translate the Legenda from the Castilian version of 1511 (see the complete reference in point 4 of the list of post-incunabula below). I provide the reader with a transcription of the original in footnotes, where I expand the abbreviations and modernize the orthography of the text. In this case, the original reads: “… porque siendo yo mujer por muchas cosas como tú[,] [S]eñor[,] sabes contradice a esto que tú me mandas. Lo uno, porque a la mujer no pertenece enseñar a los hombres; lo otro, porque la mujer es cosa despreciada por los hombres y, también, porque por cosa de la honestad no le conviene estar mezclada con los varones”. There is a digitization of one of the copies of the second edition (see note 5 below), made by the Universidad Complutense de Madrid: http://dioscorides.ucm.es/proyecto_digitalizacion/index.php?b21722559 (accessed 4 September 2019). |

| 3 | The original reads: “… Dime tú: ¿Yo no soy aquel que crié el linaje humano, y formé la distinción de hombre y mujer, y derramo la gracia de mi espíritu donde quiero? Cerca de mí no hay diferencia de hombre a mujer, ni de aldeano a noble”. |

| 4 | Catalina García (1889, p. 7, number 7 and p. 8, number 9) registers two different editions of this translation (27 March 1511 and 26 June 1511, respectively). Their typographical differences are described by Martín Abad (1991, pp. 212–13). In the following pages, I focus my analysis on copies of the second edition (26 June 1511), to which most of the surviving copies pertain. For other vulgarizations of the Legenda maior, see (Nocentini 2013b, esp. pp. 175–77 (Italian) and Schultze 2013 (English)). |

| 5 | I expand the abbreviations and respect the original orthography of the titles. |

| 6 | This is the main objective of my Project Late Medieval Visionary Women’s Impact in Early Modern Castilian Spiritual Tradition (Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 842094). |

| 7 | “… que ansí fuese [la leyenda] más comunicada y a todos fuese común y a todos aprovechase más”. Since the foliation of the book starts in “Chapter One”, the previous first two Prologues (the translator’s and Raimondo da Capua’s) are not numbered. For this reason, I provide a Roman number between square brackets, counting the folios from the first page of the first prologue. |

| 8 | This wider target of the Cisnerian reform is discussed in (Acosta-García, forthcoming b). |

| 9 | The original reads: “Y así vino a mis manos un libro en latín que contiene muy largamente toda la dicha leyenda”. |

| 10 | The original title reads: “Epístola que escribió un religioso de la Cartuja, respondiendo a otra que le hubo escrito fray Thomas Antonio de Sena de la Orden de los frailes Predicadores sobre las cosas maravillosas de la vida y muerte de Santa Caterina de Siena”. |

| 11 | I thank Silvia Nocentini for her help in identifying this epistle. For the Epistle’s text, see (Société des Bollandistes 1643, pp. 969–70), and (Laurent 1942, pp. 258–73). |

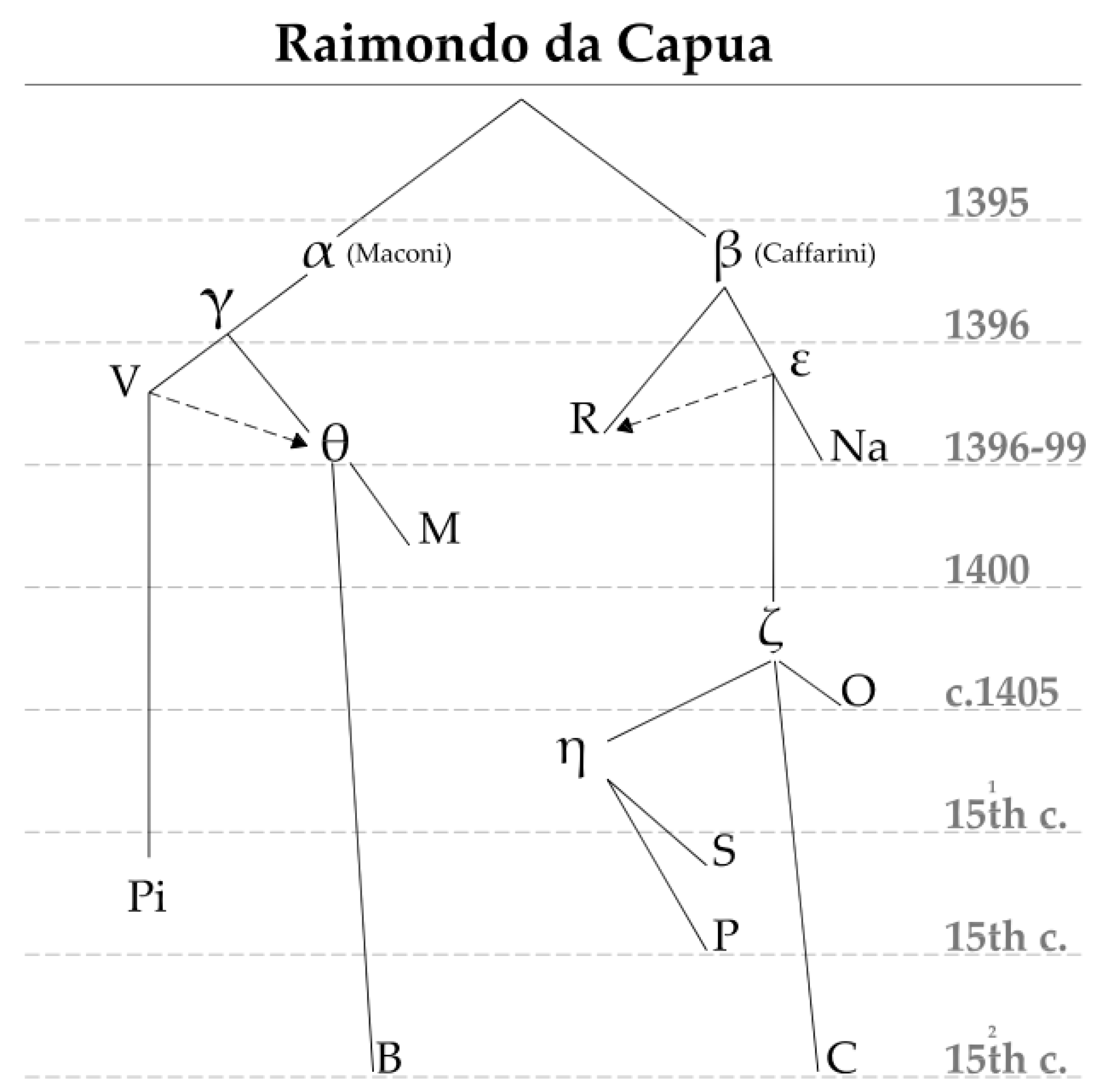

| 12 | I will use the abbreviations of the manuscript catalogue in (Nocentini 2013a, pp. 39–68). I thank Silvia Nocentini for the supplementary codicological details provided via private mail. B = Bologna, Biblioteca Universitaria 1741, it has a date: “14 February 1485”; C = Cesena, Biblioteca Malatestiana, S. XXIX.17, according to (Nocentini 2013a, p. 44), “seconda metà del XV sec.”; M = Milano, Biblioteca Nazionale Braidense, AD.IX.38, according to the editor’s description (51), the text of the Legenda is from the 14th century but the Epistle is from the 15th, because the manuscript is composed of three different codicological units, with the Legenda and the Epistle in different ones. I do not include in my analysis manuscript Wsch [= Wien, Schottenstift, 207 (193), 15th century, see http://manuscripta.at/hs_detail.php?ID=28707 (accessed on 3 March 2019)], which also contains the Epistle, because its origin is not specified in Nocentini’s catalogue. |

| 13 | The original reads: “… suadir a la Santa Silla Apostólica a la canonización de la santa virgen”, in the first case, and “a manera de proceso”, in the second. |

| 14 | I also follow here the list of abbreviations of (Nocentini 2013a, pp. 39–68) (see Figure 1): R = Roma, Archivium Generale Ordinis Praedicatorum, XIV.3.24, between 1396 and 1398, from the convent of Santi Giovanni e Paolo in Venice, joins different works together and was in the possession of Tommaso da Siena; V = Città del Vaticano, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat. Lat. 10151, between 1396 and 1398, from the Convent of Saint Dominic in Orvieto, which contains just the three works; Pi = Pisa, Biblioteca Cateriniana del Seminario Arcivescovile, 24, second half of the 15th century, from the Dominican Convent of Santa Caterina de Pisa, together with different works; Na = Napoli, Biblioteca Nazionale, VIII.B.48, between 1396 and 1399, from the Dominican Convent of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva, copied in the Convent de Santi Giovani e San Paolo in Venice; and O = Oxford, Bodleian Library, Canon Misc. 205, beginning of the 15th century, from the Convent of Santi Giovanni e Paolo in Venice, which contains other lives of blessed women. The combination of Caterina, Vanna, and Margherita is also found in (b), one of the Italian vulgarizations (Nocentini 2013b, p. 176): it is the unfinished translation by Pagliaresi and it was copied in the scriptorium of Tomasso da Siena. |

| 15 | The additions by Caffarini are in the manuscripts P, O, and S, a fact that locates them in a different family of the stemma codicum (Nocentini 2013a, p. 95; see Figure 1) which is also late (15th century). This fact points to the second phase of Caffarini’s dissemination project. |

| 16 | Always keeping in mind the editorial activity of the translator, which he described in the Prologue, see note 14, above. |

| 17 | “Catherine’s prophetic and mystical charisma and her model of the disciplined penitent vocation facilitated the transformation of the Dominican penitential life from a loose association of widows into a proper religious order”. |

| 18 | “Vilas, pues, y oílas [muy grandes cosas], de manera que así como a mí a las otras personas que presentes fueron conviene muy bien decir con San Juan Evangelista: que vimos y oímos del Verbo de la vida, el cual moraba en esta maravillosa virgen, aquello y no otra cosa os anunciamos”. |

| 19 | The biblical feminine prophetic model in the Castilian translation of Angela da Foligno of 1510 is “Holda profetisa” (Acosta-García, forthcoming a). In Raimondo da Capua (1511, [ff. 1v-2r]), the main feminine biblical models are: “Ana, viuda profetisa” and “María, su hermana de Moysén con otras muchas”, plus a long list of women from the Old and New Testaments. |

| 20 | The original reads: “a los escribanos suyos que le solían escribir las cartas o epístolas” and “lo que ella dijese in raptu”, respectively. |

| 21 | “Esta santa virgen de ansí complida toda virtud también tuvo evidentísimamente espíritu de profecía y muchas cosas (estando ella en su contemplación y oración) divinalmente le fueron reveladas”. For her spirit of prophecy, see also (Raimondo da Capua 1511, f. 62r). For Vanna’s, see (Raimondo da Capua 1511, f. 108r). |

| 22 | For instance in Raimondo da Capua (1511, ff. 39r-v): “… y su espíritu tan firmemente era allegado al hacedor suyo y de todas las cosas, que por la mayor parte del tiempo quedaba sin sentidos algunos, en tanta manera que sus brazos se separaban tan recios y tan yertos juntamente con las manos, que primero los pudieran quebrantar que doblarlos ni apartarlos ni despegarlos de donde habían trabado. Otrosí en tanto que estaba actualmente ansí puesta en actual contemplación, tenía los ojos del todo cerrados y ningún sonido oía por gran ruido y sonido que hiciesen”. |

| 23 | For María’s case, the negative viewpoint given by Mártir de Anglería in his famous Epistle 428 is important (Sanmartín Bastida 2012, pp. 318–19). |

| 24 | The original reads: “cinco rayos de sangre” and “en forma de pura luz y como rayos de sol”, respectively. |

| 25 | This physicality of the wound, which other Castilian beatas such as María de Ajofrín had suffered earlier, was probed with a direct examination recorded by a notarial act (Sanmartín Bastida 2012, p. 347). Stigmata and the beatas are discussed in (Sanmartín Bastida forthcoming). |

| 26 | About the problems with the later controversy about the stigmata, the stigmatics, and the representations of Caterina in Castile, see (Huerga 1968, pp. 201–07). |

| 27 | El libro de oración, fol. A 6v, quoted in (Sanmartín Bastida 2012, p. 320). |

| 28 | The documents of the process list: “corales, granas, sombreretes, bolsa de seda, cordón de San Francisco y otras cosas de oro y plata.” |

| 29 | The original reads: “…lavarse el rostro y curarse los cabellos y pelarse las cejas…”. |

| 30 | The original reads: “defensa de su integridad espiritual y física”. |

| 31 | Food and dietary habits and night-time activities are, without any doubt, issues to be interpreted in this comparative light, because they appear both in the 1511 post-incunabulum and in the life of the living women saints of the Cisnerian reform. In a future article, I will analyze these issues in depth. |

| 32 | In this sense, as Bilinkoff (1992, p. 26) explored many years ago, María’s model of imitation followed not only Caterina’s but especially that of Lucia da Narni (See also Beltrán de Heredia 1939, pp. 129–31). |

| 33 | This is evident when reading the new sources edited by members of the Research Project “La conformación de la autoridad espiritual femenina en Castilla” (FFI2015-63625-C2-2-P, MINECO/FEDER): http://catalogodesantasvivas.visionarias.es/index.php/P%C3%A1gina_principal (accessed on 29 December 2019). |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Acosta-García, P. On Manuscripts, Prints and Blessed Transformations: Caterina da Siena’s Legenda maior as a Model of Sainthood in Premodern Castile. Religions 2020, 11, 33. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/rel11010033

Acosta-García P. On Manuscripts, Prints and Blessed Transformations: Caterina da Siena’s Legenda maior as a Model of Sainthood in Premodern Castile. Religions. 2020; 11(1):33. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/rel11010033

Chicago/Turabian StyleAcosta-García, Pablo. 2020. "On Manuscripts, Prints and Blessed Transformations: Caterina da Siena’s Legenda maior as a Model of Sainthood in Premodern Castile" Religions 11, no. 1: 33. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/rel11010033