Rice Lesion Mimic Mutants (LMM): The Current Understanding of Genetic Mutations in the Failure of ROS Scavenging during Lesion Formation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Inheritance and Genetic Definition of Rice LMMs

| Gene Mutants | Gene Locus RAP ID, MSU ID | RAP-DB Gene Symbols | CGSNL Gene Symbols | CGSNL Gene Name | Oryzabase Gene Symbol Synonyms | Oryzabase Gene Name Synonyms | Gene Product (Protein) | ProgramMed Cell Death (PCD) Phenotype | Trait Class and Mechanisms Involve | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bbs1 | Os03g0364400 LOC_Os03g24930 | OsBBS1, OsRLCK109 | BBS1 | BILATERAL BLADE SENESCENCE 1 | OsRLCK109, RLCK109, OsBBS1, OSBBS1/OsRLCK109 | Receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase 109, bilateral blade senescence 1 | Receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase | Dark brown lesions in leaves; Regulates cell death and defense responses | Disease resistance, Receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase 109 regulates cell death | [16,50] |

| cea62 | Os02g0110200, LOC_Os02g02000.1 | HPL3, OsHPL3, CYP74B2 | HPL3 | HYDROPEROXIDE LYASE 3 | OsHPL3, CYP74B2, OsCYP74B2 | Fatty acid 13-hydroperoxide lyase | Brown lesion spot over the entire leaf surface | Disease resistance, insect resistance, viral disease resistance; Due to constitutive induction of JA signaling | [51,52] | |

| csfl6 | Os08g0160500 LOC_Os08g06380.1 | CSLF6, OsCslF6, OsCSLF6 | CSLF6 | CELLULOSE SYNTHASE LIKE F6 | OsCslF6, OsCSLF6, OsCLD3, CLD3 | MLG (mixed-linkage glucan) synthase | Spontaneous, discrete, necrotic lesions in flag and old leaves | Due to a decrease in mixed-linkage glucan contents | [53] | |

| lil1 | Os07g0488400 LOC_Os07g30510 | LIL1 | LIL1 | LIGHT-INDUCED LESION MIMIC MUTANT 1 | Light-induced lesion mimic mutant 1 | Cysteine-rich receptor-like kinase (CRK), | Light-induced, small, rust-red lesions on the leaf; accumulation of ROS; PCD | LMM, Disease resistance; Putative cysteine-rich receptor-like kinase (CRK) casual light-induced LMM | [17] | |

| llm1 | Os04g0610800 LOC_Os04g52130.1 | RLIN1 | RICE LESION INITIATION 1 | CPO, CPOX, LLM1, HEMF | Coproporphyrinogen III oxidase, leaf lesion mimic mutant | Coproporphyrinogen III oxidase | Showed programmed cell death and accumulated ROS | LMM, Stress tolerance; Chloroplast damage in lesion formation in rice | [54] | |

| spl3 | Os03g0160100 | OsSPL3, LCRN1 | SPL3, OsEDR1 ACDR1 | SPOTTED LEAF3 (SPL3) | OsEDR1, OsACDR1, EDR1 | Tolerance and resis- tance, lesi- on mimic, | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase (MAPKKK), | lesion spots on leaves at the late tiller- ing stage | caused direct- ly by excess amounts of H2O2 accumulation | [55] |

| lms | Os02g0639000 | LMS, OsLMS | LMS | LESION MIMIC AND SENESCENCE | OsLMS | Double-stranded RNA binding domain (dsRBD) containing protein | Reddish-brown lesions on leaves and rapid senescence after flowering | Failure of regulating the stress responses | [56] | |

| lsd1 | Os08g0159500 LOC_Os03g43840.1 | OsLOL1, OsLSD1 | OsLSD1, OsLOL1, OsLSD1.1, LSD1.1, LSD1 | Zinc finger protein LSD1, LESION SIMULATING DISEASE1.1, | C2C2-type zinc finger protein | Regulates PCD and callus differentiation | Negative regulator of PCD and hypersensitive response (HR) | [57] | ||

| mlo | Os06g0486300 | OsMLO2 | MLO_ | POWDERY-MILDEW-RESISTANCE GENE O_ | OsMLO6, OsMLO1, OsMlo1, Mlo, OsMlo-1, Mlo1, | Powdery-mildew-resistance gene O6, | MLO-like protein 1 | Modulating defense responses and cell death | Involved in modulation of pathogen defense and cell death. Ca2+-dependent calmodulin-binding | [58] |

| Sl | Os12g0268000 LOC_Os01g50520.1 | SEKIGUCHI LESION | OsSL | SEKIGUCHI LESION | OsSL, spl1, CYP71P1, OsLLM1 | Sekiguchi lesion, cytochrome P450 71P1, tryptamine 5-hydroxylase, large lesion mimic 1 | Cytochrome P450 monooxygenase | Spotted lesions on leaves | Disease resistance, Cytochrome P450 monooxygenase function | [18,59] |

| spl4 | Os06g0130000 LOC_Os06g03940 | LMR, SPL4 | LRD6-6 | LESION RESEMBLING DISEASE 6-6 | LMR, LRD6-6 | Lesion resembling disease 6-6 (LRD6-6) | AAA-type ATPase, Plant spastin | Lesion formation and also affects leaf senescence in rice | LMM, disease resistance, endosomes-mediated vesicular trafficking | [60,61,62,63] |

| spl5 | Os07g0203700 LOC_Os02g04950.1 | SPL5 | SPOTTED LEAF 5 | spl5-1 | Spotted leaf5 | Putative splicing factor 3b subunit 3 (SF3b3) CPSF A subunit region | Small reddish-brown spots scattering over the whole surface of leaves | LMM, splicing factor regulates gene expression, | [49,64] | |

| spl7 | Os05g0530400 LOC_Os04g48030.1 | SPL7, | SPOTTED LEAF 7 | spl7, HSFA4D | Spotted lea , spotted leaf-7, heat stress transcription factor Spl7 | Heat stress transcription factor | Small, reddish-brown lesions over the whole surface of leaves | LMM, Balancing ROS during biotic and abiotic stress | [14,25] | |

| spl11 | Os12g0570000 LOC_Os01g60860.1 | SPL11 | SPOTTED LEAF 11 | spl11, spl11*, OsPUB11, PUB11 | Spotted leaf11; plant U-box-containing protein 11 | Protein with E3 ubiquitin ligase activity; Armadillo-like helical domain-containing protein | Chlorosis and spotted lesions on leaves in LD conditions Red spots distribute on leaf | LMM, disease resistance, E3 ligase negatively regulates PCD | [45] | |

| spl18 | Os10g0195600 | SPL18 | SPOTTED LEAF 18 | Spl18, OsAT1 | Spotted leaf 18 | Acyltransferase protein | Formation of necrotic lesion on the leaf. OsAT1 transferase protein | LMM, disease resistance, Hypersensitive reaction in tobacco | [22] | |

| spl28 | Os01g0703600 LOC_Os01g25110 | SPL28 | SPL28 | SPOTTED LEAF 28 | Clathrin-associated adaptor protein complex 1 medium subunit mu1 (AP1M1), | Spotted lesions on leaves and early senescence | Disease resistance, regulation of vesicular trafficking | [48] | ||

| spl30 | Os12g0566300 LOC_Os12g37870 | OsACL-A2, SPL30 | ACLA2 | ATP-CITRATE LYASE A2 | SPL30, OsACL-A2, ACL-A2 | Spotted leaf 30, ATP-citrate lyase A2 | Subunit A of the heteromeric ATP-citrate lyase | Negative regulation of cell death, disease resistance | LMM accumulates ROS and degrades nuclear deoxyribonucleic acids | [65] |

| spl32 | Os07g0658400 LOC_Os07g46460.1 | OsGLU, OsFd-GOGAT, Fd-GOGAT | ABC1 | ABNORMAL CYTOKININ RESPONSE 1 | OsABC1, SPL32 | Ferredoxin glutamate synthase-spotted leaf 32 | Ferredoxin-dependent glutamate synthase | The spl32 plants displayed early leaf senescence | LMM, decreased chlorophyll, upregulate superoxide dismutase | [66] |

| spl33 | Os01g0116600 LOC_Os01g02720 | SPL33 | SPL33 | SPOTTED LEAF 33 | LMM5.1, SPL33/LMM5.1 | Spotted leaf 33, lesion mimic mutant 5.1 | Eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1 alpha (eEF1A)-like protein | Negative regulation of cell death, Defense response; death and early leaf senescence | LMM, consisting of a nonfunctional zinc finger domain and three functional EF-Tu domains | [67] |

| spl35 | Os03g0205000 LOC_Os03g10750 | OsSPL35 | SPOTTED LEAF 35 | Spotted leaf 35 | CUE (coupling of ubiquitin conjugation to ER degradation) domain-containing protein | Induce cell death resulting lesion mimic mutant and enhanced disease resistance to fungal and bacterial pathogens | LMM, Decreased chlorophyll content, accumulation of H2O2, and upregulated defense-related genes | [68] | ||

| spl40 | Os05g0312000 | SPL40 | SPL40 | SPOTTED-LEAF 40 | OsMed5_1, Med5_1 | Mediator 5_1, spotted-leaf 40 | Cell death around the lesion and burst of ROS | Disease resistance; Bacterial blight resistance | [69] | |

| wsp1 | Os04g0601800 LOC_Os05g0482400 | WSP1 | WSP1 | WHITE-STRIPE LEAVES AND PANICLES 1 | OsWSP1, OsMORF2b, MORF2b | White-stripe leaves and panicles 1, multiple organellar RNA editing factor 2b | Multiple organellar RNA editing factor (MORF) family protein | Brown spots and white lesion mimic spots on the tip and leaves | Stress tolerance; brown spots and white lesion mimic spots on the tip of the leaves | [70] |

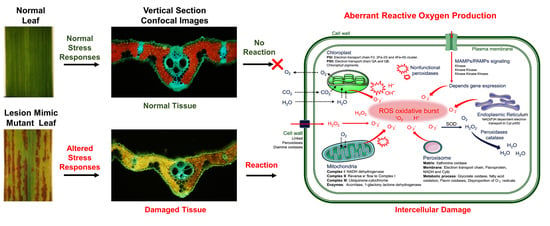

3. Development of Lesion Formation in Rice LMMs

4. Chloroplast Damage from Disrupted Photosynthetic Apparatus in LMMs

5. Chlorophyll Content and Lesion Severity

6. Reactive Oxygen Species Cause Lesions by in the PCD of the LMMs

7. Role of the MAP-Kinases Pathway in the PCD of the LMMs

8. Role of Sphingolipids in LMMs

9. Resistant to Pathogen Infection in the LMMs

10. Conclusions and Future Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Skamnioti, P.; Gurr, S.J. Against the grain: Safeguarding rice from rice blast disease. Trends Biotechnol. 2009, 27, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Greenberg, J.T.; Yao, N. The role and regulation of programmed cell death in plant–pathogen interactions. Cell. Microbiol. 2004, 6, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreasson, E.; Ellis, B. Convergence and specificity in the Arabidopsis MAPK nexus. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, J.T. Programmed cell death: A way of life for plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 12094–12097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laloi, C.; Apel, K.; Danon, A. Reactive oxygen signalling: The latest news. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2004, 7, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valandro, F.; Menguer, P.K.; Cabreira-Cagliari, C.; Margis-Pinheiro, M.; Cagliari, A. Programmed cell death (PCD) control in plants: New insights from the Arabidopsis thaliana deathosome. Plant Sci. 2020, 299, 110603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, J.; Close, P.S.; Briggs, S.P.; Johal, G.S. A novel suppressor of cell death in plants encoded by the Lls1 gene of maize. Cell 1997, 89, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lorrain, S.; Vailleau, F.; Balagué, C.; Roby, D. Lesion mimic mutants: Keys for deciphering cell death and defense pathways in plants? Trends Plant Sci. 2003, 8, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, R.A.; Delaney, T.P.; Uknes, S.J.; Ward, E.R.; Ryals, J.A.; Dangl, J.L. Arabidopsis mutants simulating disease resistance response. Cell 1994, 77, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabs, T.; Dietrich, R.A.; Dangl, J.L. Initiation of runaway cell death in an Arabidopsis mutant by extracellular superoxide. Science 1996, 273, 1853–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noutoshi, Y.; Kuromori, T.; Wada, T.; Hirayama, T.; Kamiya, A.; Imura, Y.; Yasuda, M.; Nakashita, H.; Shirasu, K.; Shinozaki, K. Loss of necrotic spotted lesions 1 associates with cell death and defense responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. 2006, 62, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouchez, O.; Huard, C.; Lorrain, S.; Roby, D.; Balagué, C. Ethylene is one of the key elements for cell death and defense response control in the Arabidopsis lesion mimic mutant vad1. Plant Physiol. 2007, 145, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yin, Z.; Chen, J.; Zeng, L.; Goh, M.; Leung, H.; Khush, G.S.; Wang, G.-L. Characterizing rice lesion mimic mutants and identifying a mutant with broad-spectrum resistance to rice blast and bacterial blight. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2000, 13, 869–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yamanouchi, U.; Yano, M.; Lin, H.; Ashikari, M.; Yamada, K. A rice spotted leaf gene, Spl7, encodes a heat stress transcription factor protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 7530–7535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xiaobo, Z.H.U.; Mu, Z.E.; Mawsheng, C.; Xuewei, C.; Jing, W. Deciphering rice lesion mimic mutants to understand molecular network governing plant immunity and growth. Rice Sci. 2020, 27, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yu, N.; Cao, Y.; Zhan, X.; Cheng, S.; Cao, L. LMM24 encodes receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase 109, which regulates cell death and defense responses in rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, T.; Gao, B.; Xiong, X. Identification and map-based cloning of the light-induced lesion mimic mutant 1 (LIL1) gene in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, G.; Wang, L.; Zhou, Z.; Leung, H.; Wang, G.-L.; He, C. Physical mapping of a rice lesion mimic gene, Spl1, to a 70-kb segment of rice chromosome 12. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2004, 272, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matin, M.N.; Suh, H.S.; Kang, S.G. Characterization of phenotypes of rice lesion resembling disease mutants. Korean J. Genet. 2006, 28, 221–228. [Google Scholar]

- Matin, M.N.; Saief, S.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Lee, D.H.; Kang, H.; Lee, D.S.; Kang, S.G. Comparative phenotypic and physiological characteristics of spotted leaf 6 (spl6) and brown leaf spot2 (bl2) lesion mimic mutants (LMM) in rice. Mol. Cells 2010, 30, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.G.; Matin, M.N.; Bae, H.; Natarajan, S. Proteome analysis and characterization of phenotypes of lesion mimic mutant spotted leaf 6 in rice. Proteomics 2007, 7, 2447–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, M.; Tomita, C.; Sugimoto, K.; Hasegawa, M.; Hayashi, N.; Dubouzet, J.G.; Ochiai, H.; Sekimoto, H.; Hirochika, H.; Kikuchi, S. Isolation and molecular characterization of a Spotted leaf 18 mutant by modified activation-tagging in rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 2007, 63, 847–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Ye, B.; Yin, J.; Yuan, C.; Zhou, X.; Li, W.; He, M.; Wang, J.; Chen, W.; Qin, P. Characterization and fine mapping of a light-dependent leaf lesion mimic mutant 1 in rice. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 97, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Jiao, R.; Wu, X.; Wang, S.; Ye, H.; Li, S.; Hu, J.; Lin, H.; Ren, D.; Wang, Y. SPL36 encodes a receptor-like protein kinase precursor and regulates programmed cell death and defense responses in rice. Res. Sq. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.V.; Vo, K.T.X.; Rahman, M.M.; Choi, S.-H.; Jeon, J.-S. Heat stress transcription factor OsSPL7 plays a critical role in reactive oxygen species balance and stress responses in rice. Plant Sci. 2019, 289, 110273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoisington, D.A.; Neuffer, M.G.; Walbot, V. Disease lesion mimics in maize: I. Effect of genetic background, temperature, developmental age, and wounding on necrotic spot formation with Les1. Dev. Biol. 1982, 93, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, C.; Hantke, S.; Grant, S.; Johal, G.S.; Briggs, S.P. The maize lethal leaf spot 1 mutant has elevated resistance to fungal infection at the leaf epidermis. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 1998, 11, 1110–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, G.; Yalpani, N.; Briggs, S.P.; Johal, G.S. A porphyrin pathway impairment is responsible for the phenotype of a dominant disease lesion mimic mutant of maize. Plant Cell 1998, 10, 1095–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeder, W.; Yoshioka, K. Lesion mimic mutants: A classical, yet still fundamental approach to study programmed cell death. Plant Signal. Behav. 2008, 3, 764–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wolter, M.; Hollricher, K.; Salamini, F.; Schulze-Lefert, P. The mlo resistance alleles to powdery mildew infection in barley trigger a developmentally controlled defence mimic phenotype. Mol. Gen. Genet. MGG 1993, 239, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büschges, R.; Hollricher, K.; Panstruga, R.; Simons, G.; Wolter, M.; Frijters, A.; Van Daelen, R.; van der Lee, T.; Diergaarde, P.; Groenendijk, J. The barley Mlo gene: A novel control element of plant pathogen resistance. Cell 1997, 88, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rostoks, N.; Schmierer, D.; Mudie, S.; Drader, T.; Brueggeman, R.; Caldwell, D.G.; Waugh, R.; Kleinhofs, A. Barley necrotic locus nec1 encodes the cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel 4 homologous to the Arabidopsis HLM1. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2006, 275, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keisa, A.; Kanberga-Silina, K.; Nakurte, I.; Kunga, L.; Rostoks, N. Differential disease resistance response in the barley necrotic mutant nec1. BMC Plant Biol. 2011, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al Amin, G.M.; Kong, K.; Sharmin, R.A.; Kong, J.; Bhat, J.A.; Zhao, T. Characterization and rapid gene-mapping of leaf lesion mimic phenotype of spl-1 mutant in soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sugie, A.; Murai, K.; Takumi, S. Alteration of respiration capacity and transcript accumulation level of alternative oxidase genes in necrosis lines of common wheat. Genes Genet. Syst. 2007, 82, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abad, M.S.; Hakimi, S.M.; Kaniewski, W.K.; Rommens, C.M.T.; Shulaev, V.; Lam, E.; Shah, D.M. Characterization of acquired resistance in lesion-mimic transgenic potato expressing bacterio-opsin. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 1997, 10, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Parkhi, V.; Joshi, S.G.; Christensen, S.; Jayaprakasha, G.K.; Patil, B.S.; Kolomiets, M.V.; Rathore, K.S. A novel, conditional, lesion mimic phenotype in cotton cotyledons due to the expression of an endochitinase gene from Trichoderma virens. Plant Sci. 2012, 183, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, N.; Omura, T. Linkage analysis by reciprocal translocation method in rice plants (Oryza sativa L.): I. Linkage groups corresponding to the chromosome 1, 2, 3 and 4. Jpn. J. Breed. 1971, 21, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iwata, N.; Satoh, H.; Omura, T. Relationship between the twelve chromosomes and the linkage groups (studies on the trisomics in rice plants)(Oryza sativa L.). V. Ikushugaku Zasshi 1984, 34, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, B.; Lee, H.; Jin, Z.; Lee, D.; Koh, H.-J. Characterization and genetic mapping of white-spotted leaf (wspl) mutant in rice. Plant Breed. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, T.; Sathe, A.P.; He, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wu, J. Identification of a novel semi-dominant spotted-leaf mutant with enhanced resistance to Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae in rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sasaki, T.; Burr, B. International rice genome sequencing project: The effort to completely sequence the rice genome. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2000, 3, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohyanagi, H.; Tanaka, T.; Sakai, H.; Shigemoto, Y.; Yamaguchi, K.; Habara, T.; Fujii, Y.; Antonio, B.A.; Nagamura, Y.; Imanishi, T.; et al. The rice annotation project database (RAP-DB): Hub for Oryza sativa ssp. japonica genome information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, 741–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kawahara, Y.; de la Bastide, M.; Hamilton, J.P.; Kanamori, H.; McCombie, W.R.; Ouyang, S.; Schwartz, D.C.; Tanaka, T.; Wu, J.; Zhou, S. Improvement of the Oryza sativa Nipponbare reference genome using next generation sequence and optical map data. Rice 2013, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zeng, L.-R.; Qu, S.; Bordeos, A.; Yang, C.; Baraoidan, M.; Yan, H.; Xie, Q.; Nahm, B.H.; Leung, H.; Wang, G.-L. Spotted leaf11, a negative regulator of plant cell death and defense, encodes a U-box/armadillo repeat protein endowed with E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 2795–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vega-Sánchez, M.E.; Zeng, L.; Chen, S.; Leung, H.; Wang, G.-L. SPIN1, a K homology domain protein negatively regulated and ubiquitinated by the E3 ubiquitin ligase SPL11, is involved in flowering time control in rice. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 1456–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCouch, S.R.; Teytelman, L.; Xu, Y.; Lobos, K.B.; Clare, K.; Walton, M.; Fu, B.; Maghirang, R.; Li, Z.; Xing, Y. Development and mapping of 2240 new SSR markers for rice (Oryza sativa L.)(supplement). DNA Res. 2002, 9, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qiao, Y.; Jiang, W.; Lee, J.; Park, B.; Choi, M.; Piao, R.; Woo, M.; Roh, J.; Han, L.; Paek, N. SPL28 encodes a clathrin-associated adaptor protein complex 1, medium subunit μ1 (AP1M1) and is responsible for spotted leaf and early senescence in rice (Oryza sativa). New Phytol. 2010, 185, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hao, L.; Pan, J.; Zheng, X.; Jiang, G.; Jin, Y.; Gu, Z.; Qian, Q.; Zhai, W.; Ma, B. SPL5, a cell death and defense-related gene, encodes a putative splicing factor 3b subunit 3 (SF3b3) in rice. Mol. Breed. 2012, 30, 939–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, D.-D.; Yang, C.-C.; Qin, R.; Alamin, M.; Yue, E.-K.; Jin, X.-L.; Shi, C.-H. A guanine insert in OsBBS1 leads to early leaf senescence and salt stress sensitivity in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Cell Rep. 2018, 37, 933–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Li, F.; Tang, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, F.; Wang, G.; Chu, J.; Yan, C.; Wang, T.; Chu, C. Activation of the jasmonic acid pathway by depletion of the hydroperoxide lyase OsHPL3 reveals crosstalk between the HPL and AOS branches of the oxylipin pathway in rice. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e50089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Qi, J.; Zhu, X.; Mao, B.; Zeng, L.; Wang, B.; Li, Q.; Zhou, G.; Xu, X.; Lou, Y. The rice hydroperoxide lyase OsHPL3 functions in defense responses by modulating the oxylipin pathway. Plant J. 2012, 71, 763–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Sánchez, M.E.; Verhertbruggen, Y.; Christensen, U.; Chen, X.; Sharma, V.; Varanasi, P.; Jobling, S.A.; Talbot, M.; White, R.G.; Joo, M. Loss of cellulose synthase-like F6 function affects mixed-linkage glucan deposition, cell wall mechanical properties, and defense responses in vegetative tissues of rice. Plant Physiol. 2012, 159, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sun, C.; Liu, L.; Tang, J.; Lin, A.; Zhang, F.; Fang, J.; Zhang, G.; Chu, C. RLIN1, encoding a putative coproporphyrinogen III oxidase, is involved in lesion initiation in rice. J. Genet. Genom. 2011, 38, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.-H.; Lim, J.-H.; Kim, S.-S.; Cho, S.-H.; Yoo, S.-C.; Koh, H.-J.; Sakuraba, Y.; Paek, N.-C. Mutation of SPOTTED LEAF3 (SPL3) impairs abscisic acid-responsive signalling and delays leaf senescence in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 7045–7059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Undan, J.R.; Tamiru, M.; Abe, A.; Yoshida, K.; Kosugi, S.; Takagi, H.; Yoshida, K.; Kanzaki, H.; Saitoh, H.; Fekih, R. Mutation in OsLMS, a gene encoding a protein with two double-stranded RNA binding motifs, causes lesion mimic phenotype and early senescence in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Genes Genet. Syst. 2012, 87, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, L.; Pei, Z.; Tian, Y.; He, C. OsLSD1, a rice zinc finger protein, regulates programmed cell death and callus differentiation. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2005, 18, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, Q.; Zhu, H. Molecular evolution of the MLO gene family in Oryza sativa and their functional divergence. Gene 2008, 409, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, M.; Shibata, H.; Kihara, J.; Honda, Y.; Arase, S. Increased tryptophan decarboxylase and monoamine oxidase activities induce Sekiguchi lesion formation in rice infected with Magnaporthe grisea. Plant J. 2003, 36, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fekih, R.; Tamiru, M.; Kanzaki, H.; Abe, A.; Yoshida, K.; Kanzaki, E.; Saitoh, H.; Takagi, H.; Natsume, S.; Undan, J.R. The rice (Oryza sativa L.) LESION MIMIC RESEMBLING, which encodes an AAA-type ATPase, is implicated in defense response. Mol. Genet. Genomics 2015, 290, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Yin, J.; Liang, S.; Liang, R.; Zhou, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, W.; Wang, J.; Li, W.; He, M. The multivesicular bodies (MVBs)-localized AAA ATPase LRD6-6 inhibits immunity and cell death likely through regulating MVBs-mediated vesicular trafficking in rice. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1006311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Song, G.; Kwon, C.-T.; Kim, S.-H.; Shim, Y.; Lim, C.; Koh, H.-J.; An, G.; Kang, K.; Paek, N.-C. The rice SPOTTED LEAF4 (SPL4) encodes a plant spastin that inhibits ROS accumulation in leaf development and functions in leaf senescence. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 9, 1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Inoue, H.; Tang, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, C.; Jiang, C.-J. Rice OsAAA-ATPase1 is induced during blast infection in a salicylic acid-dependent manner, and promotes blast fungus resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ge, C.; Zhi-guo, E.; Pan, J.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, D.; Dong, G.; Hu, J.; Xue, D. Map-based cloning of a spotted-leaf mutant gene OsSL5 in Japonica rice. Plant Growth Regul. 2015, 75, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, B.; Hua, Z.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, B.; Ren, D.; Liu, C.; Yang, S.; Zhang, A.; Jiang, H.; Yu, H. Os ACL-A2 negatively regulates cell death and disease resistance in rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 1344–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, C.; Gan, T.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Niu, M.; Long, W. Isolation and characterization of a spotted leaf 32 mutant with early leaf senescence and enhanced defense response in rice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, S.; Lei, C.; Wang, J.; Ma, J.; Tang, S.; Wang, C.; Zhao, K.; Tian, P.; Zhang, H.; Qi, C. SPL33, encoding an eEF1A-like protein, negatively regulates cell death and defense responses in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 899–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wang, Y.; Ma, X.; Meng, L.; Jing, R.; Wang, F.; Wang, S.; Cheng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, L. Disruption of gene SPL 35, encoding a novel CUE domain-containing protein, leads to cell death and enhanced disease response in rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 1679–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sathe, A.P.; Su, X.; Chen, Z.; Chen, T.; Wei, X.; Tang, S.; Zhang, X.; Wu, J. Identification and characterization of a spotted-leaf mutant spl40 with enhanced bacterial blight resistance in rice. Rice 2019, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Cui, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Gu, X.; Lu, T. The RNA editing factor WSP1 is essential for chloroplast development in rice. Mol. Plant 2017, 10, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCouch, S.R. Gene nomenclature system for rice. Rice 2008, 1, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eun, L.; Ahmed, S.; Kang, S.G. Phenotype characteristics of spotted leaf 1 mutant in rice. Res. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 7, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara, T.; Maisonneuve, S.; Isshiki, M.; Mizutani, M.; Chen, L.; Wong, H.L.; Kawasaki, T.; Shimamoto, K. Sekiguchi lesion gene encodes a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase that catalyzes conversion of tryptamine to serotonin in rice. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 11308–11313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tian, D.; Yang, F.; Niu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, G.; Luo, Q.; Wang, F.; Wang, M. Loss function of SL (sekiguchi lesion) in the rice cultivar Minghui 86 leads to enhanced resistance to (hemi) biotrophic pathogens. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwata, N.; Omura, T.; Satoh, H. Linkage studies in rice (Oryza sativa L.): On some mutants for physiological leaf spots. J. Fac. Agric. Kyushu Univ. 1978, 22, 243–251. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.C.; Peter, M.E. Regulation of apoptosis by ubiquitination. Immunol. Rev. 2003, 193, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, J.A.; Shirasu, K.; Deng, X.W. The diverse roles of ubiquitin and the 26S proteasome in the life of plants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2003, 4, 948–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Shi, Y.; Yang, Y.; Feng, B.; Wei, Y.; Chen, J.; Baraoidan, M.; Leung, H.; Wu, J. Characterization and genetic analysis of a light-and temperature-sensitive spotted-leaf mutant in rice. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2011, 53, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.; Lee, G.; Kim, B.; Jang, S.; Lee, Y.; Yu, Y.; Seo, J.; Kim, S.; Lee, Y.-H.; Lee, J. Identification of a spotted leaf sheath gene involved in early senescence and defense response in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johal, G.S.; Hulbert, S.H.; Briggs, S.P. Disease lesion mimics of maize: A model for cell death in plants. Bioessays 1995, 17, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangl, J.L.; Dietrich, R.A.; Richberg, M.H. Death don’t have no mercy: Cell death programs in plant-microbe interactions. Plant Cell 1996, 8, 1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, J.; Janick-Buckner, D.; Buckner, B.; Close, P.S.; Johal, G.S. Light-dependent death of maize lls1 cells is mediated by mature chloroplasts. Plant Physiol. 2002, 130, 1894–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Penning, B.W.; Johal, G.S.; McMullen, M.D. A major suppressor of cell death, slm1, modifies the expression of the maize (Zea mays L.) lesion mimic mutation les23. Genome 2004, 47, 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arase, S.; Fukuyama, R.; Honda, Y. Light-dependent induction of sekiguchi lesion formation by bipolaris oryzae in Rice cv. Sekiguchi-asahi. J. Phytopathol. 2000, 148, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matin, M.N.; Pandeya, D.; Baek, K.-H.; Lee, D.S.; Lee, J.-H.; Kang, H.; Kang, S.G. Phenotypic and genotypic analysis of rice lesion mimic mutants. Plant Pathol J. 2010, 26, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davis, M.S.; Forman, A.; Fajer, J. Ligated chlorophyll cation radicals: Their function in photosystem II of plant photosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1979, 76, 4170–4174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, F.; Wang, G.; Li, X.; Huang, J.; Zheng, J. Heredity, physiology and mapping of a chlorophyll content gene of rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Plant Physiol. 2008, 165, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Nam, J.; Park, H.C.; Na, G.; Miura, K.; Jin, J.B.; Yoo, C.Y.; Baek, D.; Kim, D.H.; Jeong, J.C. Salicylic acid-mediated innate immunity in Arabidopsis is regulated by SIZ1 SUMO E3 ligase. Plant J. 2007, 49, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, J.Y.; Bollivar, D.W.; Bauer, C.E. Genetic analysis of chlorophyll biosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1997, 31, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ting, C.; Zheng, C.; Sathe, A.P.; Zhihong, Z.; Liangjian, L.I.; Huihui, S.; Shaoqing, T.; Xiaobo, Z.; Jianli, W.U. Characterization of a novel gain-of-function spotted-leaf mutant with enhanced disease resistance in rice. Rice Sci. 2019, 26, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J.T.; Ausubel, F.M. Arabidopsis mutants compromised for the control of cellular damage during pathogenesis and aging. Plant J. 1993, 4, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mach, J.M.; Castillo, A.R.; Hoogstraten, R.; Greenberg, J.T. The Arabidopsis-accelerated cell death gene ACD2 encodes red chlorophyll catabolite reductase and suppresses the spread of disease symptoms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, R.; Hirashima, M.; Satoh, S.; Tanaka, A. The Arabidopsis-accelerated cell death gene ACD1 is involved in oxygenation of pheophorbide a: Inhibition of the pheophorbide a oxygenase activity does not lead to the “stay-green” phenotype in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2003, 44, 1266–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pružinská, A.; Tanner, G.; Anders, I.; Roca, M.; Hörtensteiner, S. Chlorophyll breakdown: Pheophorbide a oxygenase is a Rieske-type iron–sulfur protein, encoded by the accelerated cell death 1 gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 15259–15264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pružinská, A.; Anders, I.; Aubry, S.; Schenk, N.; Tapernoux-Lüthi, E.; Müller, T.; Kräutler, B.; Hörtensteiner, S. In vivo participation of red chlorophyll catabolite reductase in chlorophyll breakdown. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hirashima, M.; Tanaka, R.; Tanaka, A. Light-independent cell death induced by accumulation of pheophorbide a in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009, 50, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yao, N.; Greenberg, J.T. Arabidopsis ACCELERATED CELL DEATH2 modulates programmed cell death. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pattanayak, G.K.; Venkataramani, S.; Hortensteiner, S.; Kunz, L.; Christ, B.; Moulin, M.; Smith, A.G.; Okamoto, Y.; Tamiaki, H.; Sugishima, M. Accelerated cell death 2 suppresses mitochondrial oxidative bursts and modulates cell death in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2012, 69, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wagner, D.; Przybyla, D.; op den Camp, R.; Kim, C.; Landgraf, F.; Lee, K.P.; Würsch, M.; Laloi, C.; Nater, M.; Hideg, E. The genetic basis of singlet oxygen–induced stress responses of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 2004, 306, 1183–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Meskauskiene, R.; Zhang, S.; Lee, K.P.; Ashok, M.L.; Blajecka, K.; Herrfurth, C.; Feussner, I.; Apel, K. Chloroplasts of Arabidopsis are the source and a primary target of a plant-specific programmed cell death signaling pathway. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 3026–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asada, K. The water-water cycle in chloroplasts: Scavenging of active oxygens and dissipation of excess photons. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 1999, 50, 601–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpinski, S.; Reynolds, H.; Karpinska, B.; Wingsle, G.; Creissen, G.; Mullineaux, P. Systemic signaling and acclimation in response to excess excitation energy in Arabidopsis. Science 1999, 284, 654–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fryer, M.J.; Ball, L.; Oxborough, K.; Karpinski, S.; Mullineaux, P.M.; Baker, N.R. Control of ascorbate peroxidase 2 expression by hydrogen peroxide and leaf water status during excess light stress reveals a functional organisation of Arabidopsis leaves. Plant J. 2003, 33, 691–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo, A.; Mühlenbock, P.; Rustérucci, C.; Chang, C.C.-C.; Miszalski, Z.; Karpinska, B.; Parker, J.E.; Mullineaux, P.M.; Karpinski, S. LESION SIMULATING DISEASE 1 is required for acclimation to conditions that promote excess excitation energy. Plant Physiol. 2004, 136, 2818–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wituszyńska, W.; Szechyńska-Hebda, M.; Sobczak, M.; Rusaczonek, A.; Kozłowska-Makulska, A.; Witoń, D.; Karpiński, S. Lesion simulating disease 1 and enhanced disease susceptibility 1 differentially regulate UV-C-induced photooxidative stress signalling and programmed cell death in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Environ. 2015, 38, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, A.; Kawasaki, T.; Henmi, K.; Shii, K.; Kodama, O.; Satoh, H.; Shimamoto, K. Lesion mimic mutants of rice with alterations in early signaling events of defense. Plant J. 1999, 17, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balagué, C.; Lin, B.; Alcon, C.; Flottes, G.; Malmström, S.; Köhler, C.; Neuhaus, G.; Pelletier, G.; Gaymard, F.; Roby, D. HLM1, an essential signaling component in the hypersensitive response, is a member of the cyclic nucleotide–gated channel ion channel family. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharma, P.; Jha, A.B.; Dubey, R.S.; Pessarakli, M. Reactive oxygen species, oxidative damage, and antioxidative defense mechanism in plants under stressful conditions. J. Bot. 2012, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schutzendubel, A.; Polle, A. Plant responses to abiotic stresses: Heavy metal-induced oxidative stress and protection by mycorrhization. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 1351–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, J.M.; Mori, I.C.; Pei, Z.; Leonhardt, N.; Torres, M.A.; Dangl, J.L.; Bloom, R.E.; Bodde, S.; Jones, J.D.G.; Schroeder, J.I. NADPH oxidase AtrbohD and AtrbohF genes function in ROS-dependent ABA signaling in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 2623–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittler, R. Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2002, 7, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.H.; Bae, Y.S.; Lee, J.S. Role of auxin-induced reactive oxygen species in root gravitropism. Plant Physiol. 2001, 126, 1055–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Torres, M.A.; Dangl, J.L.; Jones, J.D.G. Arabidopsis gp91phox homologues AtrbohD and AtrbohF are required for accumulation of reactive oxygen intermediates in the plant defense response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mittler, R.; Vanderauwera, S.; Gollery, M.; Van Breusegem, F. Reactive oxygen gene network of plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2004, 9, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raychaudhuri, S.S.; Deng, X.W. The role of superoxide dismutase in combating oxidative stress in higher plants. Bot. Rev. 2000, 66, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandalios, J.G. The rise of ROS. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2002, 27, 483–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodersen, P.; Petersen, M.; Pike, H.M.; Olszak, B.; Skov, S.; Ødum, N.; Jørgensen, L.B.; Brown, R.E.; Mundy, J. Knockout of Arabidopsis accelerated-cell-death11 encoding a sphingosine transfer protein causes activation of programmed cell death and defense. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schröder, E.; Ponting, C.P. Evidence that peroxiredoxins are novel members of the thioredoxin fold superfamily. Protein Sci. 1998, 7, 2465–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hiraga, S.; Sasaki, K.; Ito, H.; Ohashi, Y.; Matsui, H. A large family of class III plant peroxidases. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001, 42, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, L.; Sun, Q.; Qin, F.; Li, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, D.-X. Down-regulation of a SILENT INFORMATION REGULATOR2-related histone deacetylase gene, OsSRT1, induces DNA fragmentation and cell death in rice. Plant Physiol. 2007, 144, 1508–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Groom, Q.J.; Torres, M.A.; Fordham-Skelton, A.P.; Hammond-Kosack, K.E.; Robinson, N.J.; Jones, J.D.G. rbohA, a rice homologue of the mammalian gp91phox respiratory burst oxidase gene. Plant J. 1996, 10, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, A.; Tenhaken, R.; Dixon, R.; Lamb, C. H2O2 from the oxidative burst orchestrates the plant hypersensitive disease resistance response. Cell 1994, 79, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widmann, C.; Gibson, S.; Jarpe, M.B.; Johnson, G.L. Mitogen-activated protein kinase: Conservation of a three-kinase module from yeast to human. Physiol. Rev. 1999, 79, 143–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaeffer, H.J.; Weber, M.J. Mitogen-activated protein kinases: Specific messages from ubiquitous messengers. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999, 19, 2435–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamel, L.-P.; Nicole, M.-C.; Sritubtim, S.; Morency, M.-J.; Ellis, M.; Ehlting, J.; Beaudoin, N.; Barbazuk, B.; Klessig, D.; Lee, J. Ancient signals: Comparative genomics of plant MAPK and MAPKK gene families. Trends Plant Sci. 2006, 11, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.P.; Richa, T.; Kumar, K.; Raghuram, B.; Sinha, A.K. In silico analysis reveals 75 members of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase gene family in rice. DNA Res. 2010, 17, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kieber, J.J.; Rothenberg, M.; Roman, G.; Feldmann, K.A.; Ecker, J.R. CTR1, a negative regulator of the ethylene response pathway in Arabidopsis, encodes a member of the raf family of protein kinases. Cell 1993, 72, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frye, C.A.; Tang, D.; Innes, R.W. Negative regulation of defense responses in plants by a conserved MAPKK kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Xiang, C.-B. The genetic locus At1g73660 encodes a putative MAPKKK and negatively regulates salt tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2008, 67, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, C.Y.; Qi, Y.; Park, S.; Gibson, S.I. SIS 8, a putative mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase, regulates sugar-resistant seedling development in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2014, 77, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asai, T.; Tena, G.; Plotnikova, J.; Willmann, M.R.; Chiu, W.-L.; Gomez-Gomez, L.; Boller, T.; Ausubel, F.M.; Sheen, J. MAP kinase signalling cascade in Arabidopsis innate immunity. Nature 2002, 415, 977–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, T.A.; Mullen, T.D.; Obeid, L.M. A house divided: Ceramide, sphingosine, and sphingosine-1-phosphate in programmed cell death. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Biomembr. 2006, 1758, 2027–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kurusu, T.; Hamada, H.; Sugiyama, Y.; Yagala, T.; Kadota, Y.; Furuichi, T.; Hayashi, T.; Umemura, K.; Komatsu, S.; Miyao, A. Negative feedback regulation of microbe-associated molecular pattern-induced cytosolic Ca2+ transients by protein phosphorylation. J. Plant Res. 2011, 124, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, H.; Yao, N.; Song, J.T.; Luo, S.; Lu, H.; Greenberg, J.T. Ceramides modulate programmed cell death in plants. Genes Dev. 2003, 17, 2636–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greenberg, J.T.; Silverman, F.P.; Liang, H. Uncoupling salicylic acid-dependent cell death and defense-related responses from disease resistance in the Arabidopsis mutant acd5. Genetics 2000, 156, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, F.-C.; Liu, Z.; Wu, J.-X.; Liang, H.; Xi, X.-L.; Fang, C.; Sun, T.-J.; Yin, J.; Dai, G.-Y.; Rong, C. Loss of ceramide kinase in Arabidopsis impairs defenses and promotes ceramide accumulation and mitochondrial H2O2 bursts. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 3449–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shigeoka, S.; Ishikawa, T.; Tamoi, M.; Miyagawa, Y.; Takeda, T.; Yabuta, Y.; Yoshimura, K. Regulation and function of ascorbate peroxidase isoenzymes. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 1305–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.A.; Mckersie, B.D. Role of the ascorbate-glutathione antioxidant system in chilling resistance of tomato. J. Plant Physiol. 1993, 141, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Bordeos, A.; Madamba, M.R.S.; Baraoidan, M.; Ramos, M.; Wang, G.; Leach, J.E.; Leung, H. Rice lesion mimic mutants with enhanced resistance to diseases. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2008, 279, 605–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, R.; Wang, H.; Liu, Q.; Wang, D.; Zhou, X.; Xu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, W.; Chen, D.; Cao, L. Characterization and genetic analysis of the oshpl3 rice lesion mimic mutant showing spontaneous cell death and enhanced bacterial blight resistance. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 154, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizobuchi, R.; Hirabayashi, H.; Kaji, R.; Nishizawa, Y.; Yoshimura, A.; Satoh, H.; Ogawa, T.; Okamoto, M. Isolation and characterization of rice lesion-mimic mutants with enhanced resistance to rice blast and bacterial blight. Plant Sci. 2002, 163, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manigbas, N.L.; Park, D.; Park, S.; Kim, S.; Hwang, W.; Wang, H.; Kang, S.; Kang, H.; Yi, G. Rapid evaluation protocol for hydrogen peroxide and ultraviolet radiation resistance using lesion mimic mutant rice (Oryza sativa L.). Philipp. J. Crop. Sci. 2011, 36, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sasidharan, R.; Schippers, J.H.M.; Schmidt, R.R. Redox and low-oxygen stress: Signal integration and interplay. Plant Physiol. 2021, 86, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kang, S.G.; Lee, K.E.; Singh, M.; Kumar, P.; Matin, M.N. Rice Lesion Mimic Mutants (LMM): The Current Understanding of Genetic Mutations in the Failure of ROS Scavenging during Lesion Formation. Plants 2021, 10, 1598. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/plants10081598

Kang SG, Lee KE, Singh M, Kumar P, Matin MN. Rice Lesion Mimic Mutants (LMM): The Current Understanding of Genetic Mutations in the Failure of ROS Scavenging during Lesion Formation. Plants. 2021; 10(8):1598. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/plants10081598

Chicago/Turabian StyleKang, Sang Gu, Kyung Eun Lee, Mahendra Singh, Pradeep Kumar, and Mohammad Nurul Matin. 2021. "Rice Lesion Mimic Mutants (LMM): The Current Understanding of Genetic Mutations in the Failure of ROS Scavenging during Lesion Formation" Plants 10, no. 8: 1598. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/plants10081598