The Revisions of the First Autobiography of AT Still, the Founder of Osteopathy, as a Step towards Integration in the American Healthcare System: A Comparative and Historiographic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Osteopathy and Osteopathic Medicine Worldwide

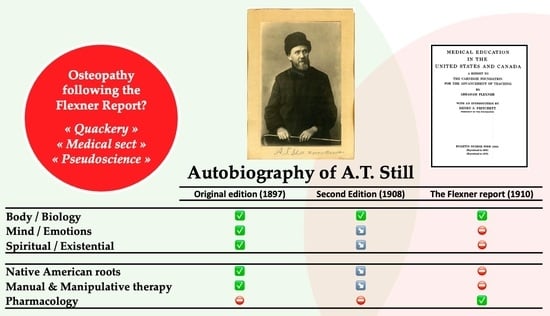

1.2. Osteopathy as a “Hands-On” Form of Alternative Medicine Seeking Recognition in the USA

1.3. The Need to Develop High Standards of Education to Secure the Future of This Emerging Profession

1.4. The Consequences of the Flexner Report on Medical and Osteopathic Education in the USA

1.5. The Crossroads for the Osteopathic Profession Regarding Dr AT Still MD, DO’s Original Ideas

1.6. The Dr AT Still, MD, DO Autobiography Written in 1897

1.7. The Revisions of the Second Edition of Dr AT Still, MD, DO’s Autobiography Occurring in the Specific Context of the American Medical Regulation Process and the Search for Recognition of the American Osteopathic Profession

2. Methods

Assessment and Analysis

- Yellow highlights indicated added text;

- Pink highlights indicated differences, and the original 1987 text was reported in the notes;

- Green highlights indicated all occurrences deemed worthy of further consideration or subsequent thought—sometimes, whole sentences were highlighted in green, while, in other cases, only a little green was added to yellow- and/or pink-highlighted sentences, to indicate minor importance.

3. Results

- Grammar and syntactic text changes made by the reviewers to correct dates, measurements, and style and to improve readability;

- Text changes introducing different nuances compared to the first edition;

- Substantial changes to the text;

- Pictures.

- Grammar and syntactic text changes made by the reviewers to correct dates, measurements, and style and improve readability: These constitute the majority of the alterations, and almost each page features many of them. The reviewers also softened overly dogmatic statements and rectified dimensions. However, most of the editing consists of modifications and additions of new words in order to improve the readability or correct the syntax; the complete list of alterations can be found in the Supplementary Materials. To provide further insight, some examples are reported in Table 1.

- Changes introducing different nuances to Dr AT Still MD, DO’s ideas and/or personality: These are not as numerous as those in the first category; however, they represent a large amount overall. In general, most amendments were made with the following aims:

- a.

- To soften overly harsh affirmations about the war—for instance, on pages 73–76, “we had the satisfaction of tearing down many flags” was changed to “we took down many flags”.

- b.

- To emphasize that Dr AT Still MD, DO was commissioned “major” (p. 75).

- c.

- To purge the word “grave-robber”, which Dr AT Still MD, DO had used in the first edition (pp. 84–85).

- d.

- To delete some playful wordings. As an example, see p. 112, where an “amusing scientific incident” was replaced with an “incident” in the second edition, and the subsequent text was also heavily amended and extended, emphasizing Dr AT Still MD, DO’s aversion to alcohol (see also the addition of “whisky” on page 170).

- e.

- To erase the referral to Indian healing methods by eliminating the following sentence on page 113: “I had no object in view when I pow-wowed the old gentleman, punched and twisted his abdomen, and told him of the awful ending of the sot, except a little street fun”.

- f.

- To remove Dr AT Still MD, DO’s reminiscence about considering to take his own life, by removing the following sentence: “I have long thought I might at some time be called to stop my useless life of misery and hours of lamentations” (p. 119). The subsequent paragraphs were also edited so that they could convey the impression of referring to a vision instead of a chronicle. On this page, Dr AT Still MD, DO writes about being saved from dejectedness by the news that his 10-year-old son had found a job to support the family. The 1897 original reads “With trembling gait my wife came to my side and said: ‘Look at our little boy of ten summers…”, while the same paragraph of the 1908 starts with “In a vision of the night of despair, I saw my wife who came to my side and said: ‘Look at our little boy of ten summers…”. Moreover, the subsequent sentences were changed accordingly, replacing “I listened” with “I seemed to listen” and “I saw” with “I seemed to see”.

- g.

- To stress Dr AT Still MD, DO’s good opinion of women (on p. 72, “wrote the golden words: ‘Forever free, without regard to race or color” was modified with an addition, “wrote the golden words: ‘Forever free, without regard to race or color,’ I will add—or sex”, and again on page 162). The cruel treatment that women had to endure because surgeons were ignorant about the law of parturition was also emphasized through the addition of the following sentence to page 133 of the 1908 edition: (Osteopathy] … teaches that lacerations to the mother and injury to the child by forceps are not necessary except in extreme cases of bone deformities”).

- h.

- To limit and/or homogenize the spiritual/religious realm, as in the examples reported in Table 2.

- 3.

- Substantial changes

- The addition of several songs, rhymes, and contributions to osteopathy, which were produced in the time interval following the first edition (after 1897) and preceding the second one (1908);

- The addition of an entirely new chapter (Chapter XXXIV, pp. 387–403);

- A sort of damnatio memoriae against Dr William Smith, who had held the first course of anatomy in 1892 and had contributed significantly to the development of the school—his name was removed in all instances in which it was feasible;

- The conversion into the masculine form of the cosmogony on pages 313–314, which originally described the Sun, the Moon, and all the planets in the feminine form (see Table 4);

- The removal of the first eight lines of Chapter XXIII, referring to a picture named "Muscular System of Man", removed from the second edition.

- 4.

- Pictures

4. Discussion

4.1. Revisions Related to Non-Physical Components of Health, Disease, and Subsequent Care

4.1.1. Less Use of Metaphors

4.1.2. Fewer References to Non-Western Sociocultural Belief Systems towards Health

4.2. Remaining Distinct in a Regulated Environment: Are Early Choices Still at Play in the Current Osteopathic Educational and Political Fields?

4.3. Different Sociocultural Contexts to Interpret Historical Osteopathic Principles

4.4. Current Perspectives for Osteopathic Education More than a Century after Dr. A.T. Still MD, DO’s Autobiography and the Flexner Report

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- OIA. The OIA Global Report: Global Review of Osteopathic Medicine and Osteopathy 2020; Osteopathic International Alliance: Chicago, IL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zegarra-Parodi, R.; Esteves, J.E.; Lunghi, C.; Baroni, F.; Draper-Rodi, J.; Cerritelli, F. The legacy and implications of the body-mind-spirit osteopathic tenet: A discussion paper evaluating its clinical relevance in contemporary osteopathic care. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2021, 41, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevitz, N. The “doctor of osteopathy”: Expanding the scope of practice. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2014, 114, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gevitz, N. The “diplomate in osteopathy”: From “school of bones” to “school of medicine”. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2014, 114, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zegarra-Parodi, R.; Baroni, F.; Lunghi, C.; Dupuis, D. Historical Osteopathic Principles and Practices in Contemporary Care: An Anthropological Perspective to Foster Evidence-Informed and Culturally Sensitive Patient-Centered Care: A Commentary. Healthcare 2022, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehl-Madrona, L.; Conte, L.A.; Mainguy, B. Indigenous roots of osteopathy. AlterNative Int. J. Indig. Peoples 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T. Osteopathic physician’ defines our identity. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 1993, 93, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevitz, N. From “Doctor of Osteopathy” to “Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine”: A Title Change in the Push for Equality. J. Osteopath. Med. 2014, 114, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevitz, N. The DOs: Osteopathic Medicine in America, 2nd ed.; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2004; 242p. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, E.R. History of Osteopathy, and Twentieth-Century Medical Practice, 2nd ed.; Caxton Press: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1924; 835p. [Google Scholar]

- The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association 1901–1911. Available online: https://archive.org/details/sim_jaoa-the-journal-of-the-american-osteopathic-association_1901-11_1_2 (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 1902. Available online: https://archive.org/details/sim_jaoa-the-journal-of-the-american-osteopathic-association_1902-11_2_3 (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- The Cleveland Meeting. 1903. Available online: https://archive.org/details/sim_jaoa-the-journal-of-the-american-osteopathic-association_1903-06_2_10 (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Varughese, H.; Shin, P. The Flexner report: Commemoration and reconsideration. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2010, 83, 149–150. [Google Scholar]

- Karle, H. How do we Define a Medical School? Reflections on the occasion of the centennial of the Flexner Report. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2010, 10, 160–168. [Google Scholar]

- Ludmerer, K. Commentary: Understanding the Flexner report. Acad. Med. J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll. 2010, 85, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, I. Complementary and alternative medicine: A review of the literature. BMJ 1998, 316, 1242–1246. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, P.M.; Bloom, B.; Nahin, R.L. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl. Health Stat. Rep. 2008, 10, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Stahnisch, F.W.; Verhoef, M. The flexner report of 1910 and its impact on complementary and alternative medicine and psychiatry in north america in the 20th century. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. Ecam 2012, 2012, 647896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevitz, N. The transformation of osteopathic medical education. Acad. Med. J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll. 2009, 84, 701–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul Lee, R. Interface: Mechanisms of Spirit in Osteopathy; Stillness Press LLC: Portland, OR, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Still, C.E., Jr. The Life and Times of A. T. STILL and His Family; Library of Congress Cataloging–in–Publication Data, Ed.; Truman State University Press: Kirksville, MI, USA, 1907; 28p. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, J. Still’s Fascia: A Qualitative Investigation to Enrich the Meaning behind Andrew Taylor Still’s Concepts of Fascia. Pahl: Jolandos, Germany, 2007; 377p. [Google Scholar]

- Are Our Osteopathic Textbooks to Go Out of Print? The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association 1908–1911: Volume 8, Page 129. Available online: https://archive.org/details/sim_jaoa-the-journal-of-the-american-osteopathic-association_1908-11_8_3/page/128/mode/2up?q=textbooks (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Osteopathic Textbooks. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association 1908–1911: Volume 8, Page 181. Available online: https://archive.org/details/sim_jaoa-the-journal-of-the-american-osteopathic-association_1908-12_8_4/page/181/mode/1up?q=books (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Trowbridge, C. Andrew Taylor Still, 1828–1917; Truman State University Press: Kirksville, MO, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J.R.A.T. Still: From the Dry Bone to the Living Man; Dry Bone Press: Blaenau Ffestiniog, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fortún Agud, M.; Estébanez de Miguel, E.; Ruiz de Escudero Zapico, A.; Cabanillas Barea, S.; Pérez Guillén, S.; López de Celis, C. La expansión de la Fisioterapia moderna de Ling por el mundo. Cuest. Fisioter. Rev. Univ. Inf. E Investig. Fisioter. 2013, 42, 166–175. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, A.S. With Thinking Fingers: The Story of William Garner Sutherland; The Cranial Academy: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 1962; 98p. [Google Scholar]

- Still, A.T. Autobiography of Andrew T. Still: With a History of the Discovery and Development of the Science of Osteopathy, Together With an Account of the…School of Osteopathy; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: Kirksville, MO, USA, 1908; 416p. [Google Scholar]

- Medicine MoO. Photo Record #1985.1003; Museum of Osteopathic Medicine: Kirksville, MO, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Medicine MoO. Object Records #1976.131; Museum of Osteopathic Medicine: Kirksville, MO, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- ASO. S. S. Twelfth Annual Announcement and Annual Catalogue o the American School of Osteopathy, Kirksville, Missouri, 1904.1905; American School of Osteopathy: Kirksville, MO, USA, 1904; Available online: https://www.atsu.edu/museum-of-osteopathic-medicine/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/1904-1905ASO.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Bean, A.S. The theory of osteopathy in nephritic cases. Osteopath. Truth 1919, 3, n.9:130-133. [Google Scholar]

- Gevitz, N. A degree of difference: The origins of osteopathy and first use of the “DO” designation. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2014, 114, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Internet Archive. Available online: https://archive.org/search?query=autobiography+A.+T.+Still (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Still, A.T. Autobiography of Andrew T. Still: With a History of the Discovery and Development of the Science of Osteopathy, Together With an Account of the…School of Osteopathy; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: Kirksville, MO, USA, 1897; 524p. [Google Scholar]

- Azarian, R.; Petrusenko, N. Historical Comparison Re-considered. Asian Soc. Sci. 2011, 7, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vann, R.T. Historiography Encyclopedia Britannica: @britannica. 2023. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/contributor/Richard-T-Vann/3043 (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- May, T. Social Research: Issues, Methods, and Process; Philadelphia Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 1993; 320p. [Google Scholar]

- Tilly, C. Big Structures, Large Processes, Huge Comparisons; Russell Sage Foundation: Cambridge, UK, 1984; 192p. [Google Scholar]

- Paulus, S. The core principles of osteopathic philosophy. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2013, 16, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildreth, A.G. The Lengthening Shadow of Dr. Andrew Taylor Still; A.G. Hildreth: Macon, MO, USA, 1938; 464p. [Google Scholar]

- Medicine MoO. Official KCOM Family about 1898; Museum of Osteopathic Medicine: Kirksville, MO, USA, 1899. [Google Scholar]

- Voegelin, C.F.; Voegelin, E.W. The Shawnee female deity in historical perspective. Am. Anthropol. 1944, 46, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethridge, R.; Shuck-Hall, S.M. Mapping the Mississippian Shatter Zone: The Colonial Indian Slave Trade and Regional Insta; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, D.M. Our Grandmother of the Shawnee Messages of a Female Deity; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the National Communication Association; ERIC Clearinghouse: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Niethammer, C. Daughters of the Earth; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2010; 450p. [Google Scholar]

- Stabb, R. “When Shawnees Die They Go To Probate Court”: Cultural Practices of the Kansas Shawnees 1830s–1860s. Algonq. Pap.-Arch. 1994, 25, 426–444. [Google Scholar]

- Haxton, J. Andrew Taylor Still: Father of Osteopathic Medicine; Truman State University Press: Kirksville, MO, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liem, T.; Lunghi, C. Reconceptualizing Principles and Models in Osteopathic Care: A Clinical Application of the Integral Theory. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2023, 29, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zegarra-Parodi, R.; Draper-Rodi, J.; Haxton, J.; Cerritelli, F. The Native American heritage of the body-mind-spirit paradigm in osteopathic principles and practices. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2019, 33–34, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, S. A road to somewhere—Endless debate about the nature of practice, the profession and how we should help patients. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2017, 26, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcuri, L.; Consorti, G.; Tramontano, M.; Petracca, M.; Esteves, J.E.; Lunghi, C. “What you feel under your hands”: Exploring professionals’ perspective of somatic dysfunction in osteopathic clinical practice-a qualitative study. Chiropr. Man. Ther. 2022, 30, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leary, M.R.; Diebels, K.J.; Davisson, E.K.; Jongman-Sereno, K.P.; Isherwood, J.C.; Raimi, K.T.; Deffler, S.A.; Hoyle, R.H. Cognitive and Interpersonal Features of Intellectual Humility. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 43, 793–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deffler, S.A.; Leary, M.R.; Hoyle, R.H. Knowing what you know: Intellectual humility and judgments of recognition memory. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 96, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, O.P.; MacMillan, A.; Draper-Rodi, J.; Vaucher, P.; Ménard, M.; Vaughan, B.; Morin, C.; Alvarez, G.; Sampath, K.K.; Cerritelli, F.; et al. Opposing vaccine hesitancy during the COVID-19 pandemic—A critical commentary and united statement of an international osteopathic research community. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2021, 39, A1–A6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciardo, A.; Sanchez, M.G.; Cobo Fernandez, M. The importance of constructing an osteopathic profession around modern common academic values and avoiding pseudoscience: The Spanish experience. Adv. Integr. Med. 2023, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, C.J.; Brockway, M.D.; Wilde, B.B. Osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT) use among osteopathic physicians in the United States. J. Osteopath. Med. 2021, 121, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J. The osteopathic philosophy of health and disease. J. Osteopath. Med. 2019, 119, 867–871. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, F.J.; D’Alonzo, G.E.; Glover, J.C.; Korr, I.M.; Osborn, G.G.; Patterson, M.M.; Seffinger, M.A.; Taylor, T.E.; Willard, F. Proposed tenets of osteopathic medicine and principles for patient care. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2002, 102, 63–65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Coulter, D. New dimensions in osteopathic medicine: Emerging perspectives on holism, healing, and the human spirit. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2018, 118, 116–117. [Google Scholar]

- Esteves, J.E.; Zegarra-Parodi, R.; van Dun, P.; Cerritelli, F.; Vaucher, P. Models and theoretical frameworks for osteopathic care—A critical view and call for updates and research. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2020, 35, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyreman, S.; Cymet, T. Osteopathic education: Editorial call for papers. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2012, 15, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballestra, E.; Battaglino, A.; Cotella, D.; Rossettini, G.; Sanchez-Romero, E.A.; Villafane, J.H. ¿Influyen las expectativas de los pacientes en el tratamiento conservador de la lumbalgia crónica? Una revisión narrativa (Do patients’ expectations influence conservative treatment in Chronic Low Back Pain? A Narrative Review). Retos 2022, 46, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossettini, G.; Palese, A.; Geri, T.; Fiorio, M.; Colloca, L.; Testa, M. Physical therapists’ perspectives on using contextual factors in clinical practice: Findings from an Italian national survey. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Audoux, C.R.; Estrada-Barranco, C.; Martínez-Pozas, O.; Gozalo-Pascual, R.; Montaño-Ocaña, J.; García-Jiménez, D.; Vicente de Frutos, G.; Cabezas-Yagüe, E.; Sánchez Romero, E.A. What Concept of Manual Therapy Is More Effective to Improve Health Status in Women with Fibromyalgia Syndrome? A Study Protocol with Preliminary Results. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, M.; de Medeiros, R.; Mosini, A.C. Are We Ready for a True Biopsychosocial-Spiritual Model? The Many Meanings of “Spiritual”. Medicines 2017, 4, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegarra-Parodi, R.; Draper-Rodi, J.; Cerritelli, F. Refining the biopsychosocial model for musculoskeletal practice by introducing religion and spirituality dimensions into the clinical scenario. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2019, 32, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Page (1908) | 1897 | 1908 |

|---|---|---|

| 17 | I suppose I bawled, and filled the bill of nature in the baby life. My mother was as others who had five or six angels to yell all night for her comfort. | I suppose I cried, and filled the bill of nature in the baby life. My mother was as others who had five or six children to yell all night for her comfort. |

| 47 | He raised his head two feet in the air, and fixed those basilisk orbs on me. | He raised his head two feet above the ground, and fixed his eyes on me. |

| 58 | This feeling of duty to free all and let each person have an equal chance to so live this life as a part of a vast eternity, preparatory to joys immortal, which were bought and paid for by the life and blood of the Son of God, continued to grow… | This feeling of duty to free all and let each person have an equal chance to so live this life as a part of a vast eternity, preparatory to another life, continued to grow… |

| 96 | I determined to try my luck with what I then thought to be a new discovery. | I determined to try my luck in the introduction of what I had proven to be a new discovery and a remedy for human ills. |

| 101 | A few months later I found a man in great distress with asthma. I got off my horse and “hoodledooed” him. | A few months later as I was driving across the country on business, I found a man in great distress, suffering with an attack of asthma. The day was cold but the man sat out of doors astride a chair with his face to the back of it; he was gasping for breath and suffering so much that his family, helpless to relieve him, stood around him crying. I quickly dismounted and “hoodledooed” him, or in other words, I treated him, giving him relief at once, and he has had no return of the asthma during the six years which have passed since the treatment was given him. |

| 193 | …when driven by the power of life at the command of God, who gives power to all elements of force that exist beneath the great throne of mind… | …when driven by the power of life, which controls all the elements of force that exist… |

| 232 | Osteopathy—a drugless science—finds the utero- genital nerves made tight by the fastening of certain segments. | Osteopathy—a drugless science—finds the utero- genital nerves deranged by irritation. |

| Page (1908) | 1897 | 1908 |

|---|---|---|

| 163 | We are not enrolled under the banner of a theologian. | We are not enrolled under the banner of a theorist. |

| 178 | …I have been visited by the visions of the night… | …I have been visited by visions in the night… |

| 185 | God would not be forgetful […] and there is much evidence that mind is imparted to the corpuscles of the blood… | Nature would not be forgetful […] and there is much evidence that knowledge is imparted to the corpuscles of the blood … |

| 186 | You dare not assert that the Deity… | You dare not assert that God… |

| 202 | Death is completed work of development of the sum total of effect to a finished work of nature. | Death is the end or the sum total of effects. |

| 208 | … angels and worlds, are atoms of which you are composed. […] Therefore be kind in thought to the atoms of life, or in death you will be borne to the grave by the beasts of burden who carry nothing to the tombs but the bodies of heedless stupidity, the mourners being the asses who cry and bray over the loss of their dear brother. | … angels and worlds, are atoms. […] Therefore be kind in thought to the atoms of life. |

| 209 | Let us reason with a faith that nature does know… | Let us reason with a thought that nature does know… |

| 291 | …by simply adjusting the vocal organs. Deity created the organs, and also the law of their adjustment when out of order; neither did He mistake in the creation, nor in the law. … produced by the use of calomel alone. | …by simply adjusting the vocal structure. Nature formed the organs, and framed the law of their adjustment and made no mistake in the formation, nor in the law… produced by them. |

| 330 | He is surprised to find that man is made by the eternal, unerring Architect. | He is surprised to find that man was made by an unerring Architect. |

| 330 | The thoughts of God himself are found in every drop of your blood. | The wisdom of Nature’s architect is found in every drop of your blood. |

| 332 | …from the bosom of God. | …from the bosom of Nature. |

| 343 | The arteries bring the blood and wash it with the spirit of life. | The arteries bring the blood of life and construct man, beast and all other bodies. |

| Page (1908) | 1897 | 1908 |

|---|---|---|

| 96 | I determined to try my luck with what I then thought to be a new discovery. | I determined to try my luck in the introduction of what I had proven to be a new discovery and a remedy for human ills. |

| 133 | They know it falls to their lot to bear all the suffering and lacerations; therefore it is reasonable to suppose, for the sake of their sex, they will continue the study of the laws of parturition to a comprehensive and practical knowledge of all the principles belonging to this branch of Osteopathy. | They know it falls to their lot to bear all the suffering and lacerations received through the ignorance of the doctor; therefore it is reasonable to suppose, for the sake of their sex, they will continue to study the law of parturition and gain a comprehensive and practical knowledge of all the principles belonging to this branch of Osteopathy, which teaches that lacerations to the mother and injury to the child by forceps are not necessary except in extreme cases of bone deformities. |

| 159 | …that arterial action has been increased by heat to such velocity that veins cannot return blood. Contract veins, and stop the equality of exchange between veins and arteries. | …that arterial action has been increased by sun-heat to such velocity that veins cannot return blood normally, but they become contracted, stopping the equality of exchange between veins and arteries. Then a chill follows for a short time, then fever. |

| 182 | He who wished to successfully solve the problem of disease or deformities of any kinds in all cases without exception would find one or more obstruction in some artery, or some of its branches. | He who wished to successfully solve the problem of disease or deformity of any kind in every case without exception would find one or more obstructions in some artery, or vein. |

| 182 | …further proclaimed that the brain of man was God’s drug-store… | …further proclaimed that the body of man was God’s drug-store… |

| 184 | Greek lexicographers say it is a proper name for a science founded on a knowledge of bones. So instead of “bone disease” it really means “usage.” | I reasoned that the bone, “Osteon”, was the starting point from which I was to ascertain the cause of pathological conditions, and so I combined the “Osteo” with the “pathy” and had as a result, Osteopathy. |

| 200 | …any system of drugs, which is your most deadly enemy. A doctor will use you for what money he can get out of you. | …any system of drugs, which is your most deadly enemy. |

| 203 | …found at the origin of the gall-producing nerves in the brain. Therefore when we are suffering from the effect of delays in cardiac nerves to forward blood in sufficient quantities to supply cervix, we have as cause of such pain simply too feeble motion to start blood to an action of its latent vitality. Thus you have quantity and quality minus motion to the degree of heat by which magnetism can begin the work of vital repairs, or association of the principles of the crude elements of nature, and construct a suitable superstructure in which life can only dwell. | …found at the origin of the gall-producing nerves. Therefore when we are suffering from the effect of any delay in the nerves to send forward nourishment in sufficient quantities, we have as cause of such pain simply a too feeble motion with which to start blood into action. |

| 206 | The powers of lymph are not known. A quantity of blood may be thrown from a ruptured vein or artery and form a large tumefaction of the parts, causing a temporary suspension of the vital there-unto belonging. | The functions of lymph are not known. A quantity of blood may be thrown from a ruptured vein or artery and form a large tumefaction, causing a temporary suspension of the vital forces. |

| 306 | God has forgotten nothing, and we find a supply of uric acid for destroying stone in bladder or gall stones. | God has forgotten nothing, and we find a supply of uric acid which will destroy stone in the urinary bladder. His law is equally trustworthy in the destruction of gall stones. |

| 326 | What can you give us in place of drugs? we cannot add or give anything from the material world… | What can you give us in place of drugs? we can give you adjustment of structure but we cannot add or give anything from the material world… |

| 326 | … substances that have been made so by wear and motion. | … substances that have been made so by wear and motion. A perfectly adjusted body which will produce pure blood and plenty of it, deliver it on time and in quantity sufficient to supply all demands in the economy of life. This is what the osteopath can give you in the place of drugs if he knows his business. |

| Page (1908) | 1897 | 1908 |

|---|---|---|

| 126 | Dr. William Smith, of Edinburgh, Scotland, came to my house to talk with me and learn something of the law of cures,… | a doctor from Edinburgh, Scotland, came to my house to talk with me and learn something of the law,… |

| 132 | …from a competent instructor, as I believed Dr. William Smith to be at that time. Since then he has satisfied me that he is the best living anatomist on earth, his head and scalpel prove that he is as good as the best of any medical college of Europe or America. Since leaving Edinburgh, he has studies and dissected to the extent of the demands of Osteopathy for four years, which makes at least two years further in its qualification for the purpose of remedies. Thus I feel safe in saying that Dr. Smith is to-day the wisest living anatomist on the globe, and will await the successful refutation of the assertion. | …from a competent instructor. |

| 313 | The central figure of the group, Mother Sun, illumines space with her effulgent rays, and lights the pathway of numerous children and grandchildren too. She is a matchless mother, and guides her children well; each one of them is polished to the highest point of perfection known to skill. … in the grand plan which the mother has on constant exhibition. | The central figure of the group, Father Sun, illumines space with his effulgent rays, and lights the pathway of numerous children and grandchildren too. He is a matchless father, and guides his children well; each one of them is polished to the highest point of perfection. … in the grand plan which is on constant exhibition. |

| 313 | Small Mercury dwells close unto her mother’s side, as if she feared to wander away lest she be lost in fields of space. She is arrayed in robes of vivid white, without a spot to mar her purity. | Small Mercury dwells close unto his father’s side, as if he feared to wander away lest he be lost in fields of space. He is arrayed in robes of vivid white, without a spot to mar his purity. |

| 313 | …to gladden her Mother’s heart and help increase the starry progeny. The eldest child of all, Mrs. Uranus, … of the old grandmother… Her family… I saw the gay, vivacious Mrs. Saturn, with her many rings. She smiled on… Moon, and shed the light… | …to gladden her Father’s heart and help increase the starry progeny. The eldest child of all, Uranus, … of the old grandparent… His family… I saw Saturn, with his many rings. He smiled on… Moon, that shed the light… |

| 314 | …of the lady Sun, and followed with unfaltering footsteps the line of march she had laid out for them. I saw the face of the dear mother shrouded by a veil of impenetrable mourning, as if her heart were grieved by some erring action of one of her beauteous family…and revealed her face… She sent this message… | …of the Sun, and followed with unfaltering footsteps the line of march laid out for them. I saw the face of the dear parent shrouded by a veil of impenetrable mourning, as if the heart were grieved by some erring action of one of the beauteous family… and revealed a face…Sending this message… |

| Page (1908) | 1897 | 1908 |

|---|---|---|

| Frontispiece | Portrait of Dr. A.T. Still | Different Portrait of Dr. A.T. Still |

| 132 | Picture of William Smith, M.D., D.O. (page 154) | Removed |

| 136 | Picture “My name is Scarlet Fever; I live on little blue-eyed, fair-skinned children” between pages 160 and 161 | Removed |

| 143 | “A.T. Still’s Infirmary and school building” (between pages 168 and 169) | Acronym “A.S.O.” added on the roof |

| 147 | Picture, portrait: “Mrs. Anne Morris, the amanuensis who wrote this volume according to my dictation” (table between pages 172 and 173) | Removed |

| 206 | Picture: “Bust of A.T. Still” (table between pages 250 and 51) | Removed |

| 256 | Color picture: “Professor Peacock” (table between pages 316 and 17) | Removed |

| 366 | Picture: “It is because you have lied” | Moved from the end of Chapter XXXI to the second page of Chapter XXXII |

| 366 | Picture “Muscular System of Man” (Anatomical table between pages 442 and 43) | Removed |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tuscano, S.C.; Haxton, J.; Ciardo, A.; Ciullo, L.; Zegarra-Parodi, R. The Revisions of the First Autobiography of AT Still, the Founder of Osteopathy, as a Step towards Integration in the American Healthcare System: A Comparative and Historiographic Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 130. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/healthcare12020130

Tuscano SC, Haxton J, Ciardo A, Ciullo L, Zegarra-Parodi R. The Revisions of the First Autobiography of AT Still, the Founder of Osteopathy, as a Step towards Integration in the American Healthcare System: A Comparative and Historiographic Review. Healthcare. 2024; 12(2):130. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/healthcare12020130

Chicago/Turabian StyleTuscano, Silvia Clara, Jason Haxton, Antonio Ciardo, Luigi Ciullo, and Rafael Zegarra-Parodi. 2024. "The Revisions of the First Autobiography of AT Still, the Founder of Osteopathy, as a Step towards Integration in the American Healthcare System: A Comparative and Historiographic Review" Healthcare 12, no. 2: 130. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/healthcare12020130