Voriconazole-Induced Squamous Cell Carcinoma after Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Showing Early-Stage Vascular Invasion

Abstract

:1. Introduction

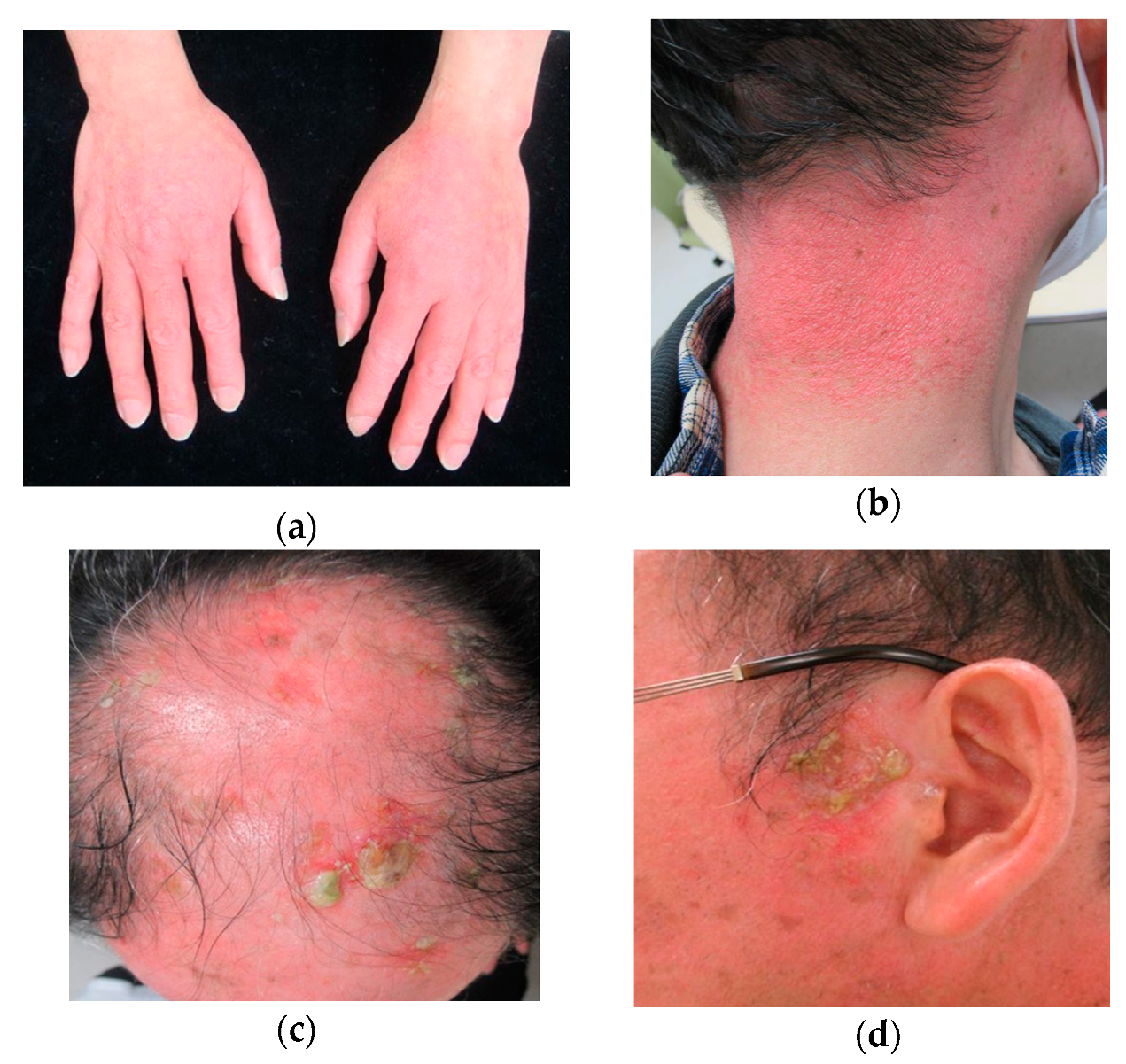

2. Case Report

3. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kuklinski, L.F.; Li, S.; Karagas, M.R.; Weng, W.K.; Kwong, B.Y. Effect of voriconazole on risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer after hematopoietic cell transplantation. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2017, 77, 712–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cowen, E.W.; Nguyen, J.C.; Miller, D.D.; McShane, D.; Arron, S.T.; Prose, N.S.; Turner, M.L.; Fox, L.P. Chronic phototoxicity and aggressive squamous cell carcinoma of the skin in children and adults during treatment with voriconazole. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2010, 62, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Morice, C.; Acher, A.; Soufir, N.; Michel, M.; Comoz, F.; Leroy, D.; Verneuil, L. Multifocal Aggressive Squamous Cell Carcinomas Induced by Prolonged Voriconazole Therapy: A Case Report. Case Rep. Med. 2010, 2010, 351084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Williams, K.; Mansh, M.; Chin-Hong, P.; Singer, J.; Arron, S.T. Voriconazole-Associated Cutaneous Malignancy: A Literature Review on Photocarcinogenesis in Organ Transplant Recipients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 58, 997–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Epaulard, O.; Villier, C.; Ravaud, P.; Chosidow, O.; Blanche, S.; Mamzer-Bruneel, M.F.; Thiébaut, A.; Leccia, M.T.; Lortholary, O. A Multistep Voriconazole-Related Phototoxic Pathway May Lead to Skin Carcinoma: Results From a French Nationwide Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 57, e182–e188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, R.E.; Metayer, C.; Rizzo, J.D.; Socié, G.; Sobocinski, K.A.; Flowers, M.E.D.; Travis, W.D.; Travis, L.B.; Horowitz, M.M.; Deeg, H.J. Impact of chronic GVHD therapy on the development of squamous-cell cancers after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: An international case-control study. Blood 2005, 105, 3802–3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaulagain, C.P.; Sprague, K.A.; Pilichowska, M.; Cowan, J.; Klein, A.K.; Kaul, E.; Miller, K.B. Clinicopathologic characteristics of secondary squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck in survivors of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for hematologic malignancies. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2019, 54, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokota, A.; Ozawa, S.; Masanori, T.; Akiyama, H.; Ohshima, K.; Kanda, Y.; Takahashi, S.; Mori, T.; Nakaseko, C.; Onoda, M.; et al. Secondary solid tumors after allogeneic hematopoietic SCT in Japan. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012, 47, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ona, K.; Oh, D.H. Voriconazole N-oxide and its ultraviolet B photoproduct sensitize keratinocytes to ultraviolet A. Br. J. Dermatol. 2015, 173, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norval, M. The mechanisms and consequences of ultraviolet-induced immunosuppression. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2006, 92, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malani, A.N.; Aronoff, D.M. Voriconazole-Induced Photosensitivity. Clin. Med. Res. 2008, 6, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Miller, D.D.; Cowen, E.W.; Nguyen, J.C.; McCalmont, T.H.; Fox, L.P. Melanoma Associated with Long-term Voriconazole Therapy. Arch. Dermatol. 2010, 146, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Atsushi, K. Dysfunctions of natural killer cells. Jpn. J. Pediatr. Hematol. 1989, 3, 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Feist, A.; Lee, R.; Osborne, S.; Lane, J.; Yung, G. Increased incidence of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in lung transplant recipients taking long-term voriconazole. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2012, 31, 1177–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.R.; Turner, M.L.; Baird, K.; Gea-Banacloche, J.; Mitchell, S.; Pavletic, S.Z.; Wise, B.; Cowen, E.W. Voriconazole-Induced Phototoxicity Masquerading as Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease of the Skin in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplant Recipients. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009, 15, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sawada, Y.; Nakai, Y.; Yokota, N.; Habe, K.; Hayashi, A.; Yamanaka, K. Voriconazole-Induced Squamous Cell Carcinoma after Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Showing Early-Stage Vascular Invasion. Dermatopathology 2020, 7, 48-52. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/dermatopathology7030008

Sawada Y, Nakai Y, Yokota N, Habe K, Hayashi A, Yamanaka K. Voriconazole-Induced Squamous Cell Carcinoma after Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Showing Early-Stage Vascular Invasion. Dermatopathology. 2020; 7(3):48-52. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/dermatopathology7030008

Chicago/Turabian StyleSawada, Yumi, Yasuo Nakai, Naho Yokota, Koji Habe, Akinobu Hayashi, and Keiichi Yamanaka. 2020. "Voriconazole-Induced Squamous Cell Carcinoma after Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Showing Early-Stage Vascular Invasion" Dermatopathology 7, no. 3: 48-52. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/dermatopathology7030008