Inhibitory Effect of Synthetic Flavone Derivatives on Pan-Aurora Kinases: Induction of G2/M Cell-Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis in HCT116 Human Colon Cancer Cells

Abstract

:1. Introduction

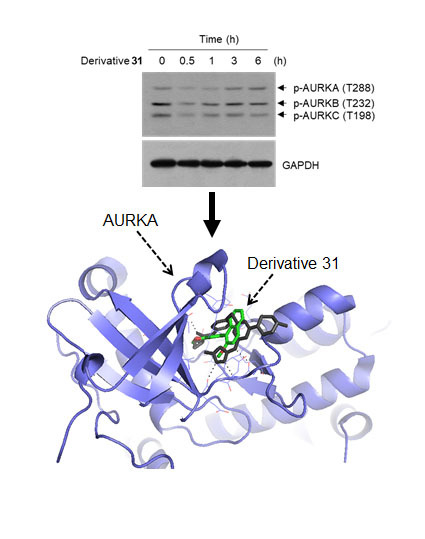

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Preparation of 36 Synthetic Flavone Derivatives

3.2. Cell Culture

3.3. Clonogenic Long-Term Survival Assay

3.4. Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship (QSAR)

3.5. Cell-Cycle Analysis by Flow Cytometry

3.6. Apoptosis Assay by Annexin V Staining

3.7. Western Blotting Analysis

3.8. In-Silico Docking

3.9. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GI50 | cell growth inhibitory concentration |

| AURKA | aurora kinase A |

| AURKB | aurora kinase B |

| AURKC | aurora kinase C |

| CoMFA | comparative molecular field analysis |

| CoMSIA | comparative molecular similarity indices analysis |

| 3D-QSAR | Three-dimensional quantitative structure–activity relationship |

| PARP | poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase |

| TPB | 4-[(4-[2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]amino]pyrimidin-2-yl)amino]benzoic acid |

| FITC | fluorescein isothiocyanate |

References

- Lin, C.H.; Chang, C.Y.; Lee, K.R.; Lin, H.J.; Chen, T.H.; Wan, L. Flavones inhibit breast cancer proliferation through the Akt/FOXO3a signaling pathway. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gade, S.; Gandhi, N.M. Baicalein Inhibits MCF-7 Cell Proliferation In Vitro, Induces Radiosensitivity, and Inhibits Hypoxia Inducible Factor. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 2015, 34, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surichan, S.; Arroo, R.R.; Ruparelia, K.; Tsatsakis, A.M.; Androutsopoulos, V.P. Nobiletin bioactivation in MDA-MB-468 breast cancer cells by cytochrome P450 CYP1 enzymes. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 113, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, Q.; Song, W.; Xu, D.; Ma, Y.; Li, F.; Zeng, J.; Zhu, G.; Wang, X.; Chang, L.S.; He, D.; et al. Kaempferol suppresses bladder cancer tumor growth by inhibiting cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis. Mol. Carcinog. 2015, 54, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samarghandian, S.; Afshari, J.T.; Davoodi, S. Chrysin reduces proliferation and induces apoptosis in the human prostate cancer cell line pc-3. Clinics 2011, 66, 1073–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jung, Y.; Shin, S.Y.; Yong, Y.; Jung, H.; Ahn, S.; Lee, Y.H.; Lim, Y. Plant-derived flavones as inhibitors of aurora B kinase and their quantitative structure-activity relationships. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2015, 85, 574–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.S.; Koh, E.J.; Jung, Y.; Shin, S.Y.; Lim, Y. 1H and 13C NMR spectral assignments of flavone derivatives. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2017, 55, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, B.M.; Cosby, R.; Quereshy, F.; Jonker, D. Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Stage II and III Colon Cancer Following Complete Resection: A Cancer Care Ontario Systematic Review. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 29, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannarkatt, J.; Joseph, J.; Kurniali, P.C.; Al-Janadi, A.; Hrinczenko, B. Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Stage II Colon Cancer: A Clinical Dilemma. J. Oncol. Pract. 2017, 13, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, Y.; Sugihara, K. Adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer: The difference between Japanese and western strategies. Expert. Opin. Pharmacother. 2016, 17, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franken, N.A.; Rodermond, H.M.; Stap, J.; Haveman, J.; van Bree, C. Clonogenic assay of cells in vitro. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 2315–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.S.; Shin, S.Y.; Ahn, S.; Koh, D.; Lee, Y.H.; Lim, Y. Biological evaluation of 2-pyrazolinyl-1-carbothioamide derivatives against HCT116 human colorectal cancer cell lines and elucidation on QSAR and molecular binding modes. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2017, 25, 5423–5432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, K.Y.; Park, J.; Han, Y.S.; Lee, Y.H.; Shin, S.Y.; Lim, Y. Synthesis and biological evaluation of hesperetin derivatives as agents inducing apoptosis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2017, 25, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, J.S.; Lim, Y.; Koh, D. Crystal structure of 2-(3,4-di-meth-oxy-phen-yl)-3-hy-droxy-4H-chromen-4-one. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E Struct. Rep. Online 2014, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; Lim, Y.; Koh, D. Crystal structure of 2-(2,3-di-meth-oxy-naphthalen-1-yl)-3-hy-droxy-6-meth-oxy-4H-chromen-4-one. Acta Crystallogr. E Crystallogr. Commun. 2015, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Zhang, M.G.; Wang, X.J.; Zhong, S.; Shao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Shen, Z.J. AURKA suppression induces DU145 apoptosis and sensitizes DU145 to docetaxel treatment. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2013, 5, 359–367. [Google Scholar]

- Nigg, E.A. Mitotic kinases as regulators of cell division and its checkpoints. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001, 2, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, A.O.; Seghezzi, W.; Korver, W.; Sheung, J.; Lees, E. The mitotic serine/threonine kinase Aurora2/AIK is regulated by phosphorylation and degradation. Oncogene 2000, 19, 4906–4916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bischoff, J.R.; Anderson, L.; Zhu, Y.; Mossie, K.; Ng, L.; Souza, B.; Schryver, B.; Flanagan, P.; Clairvoyant, F.; Ginther, C.; et al. A homologue of Drosophila aurora kinase is oncogenic and amplified in human colorectal cancers. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 3052–3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lum, J.J.; Bauer, D.E.; Kong, M.; Harris, M.H.; Li, C.; Lindsten, T.; Thompson, C.B. Growth factor regulation of autophagy and cell survival in the absence of apoptosis. Cell 2005, 120, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andree, H.A.; Reutelingsperger, C.P.; Hauptmann, R.; Hemker, H.C.; Hermens, W.T.; Willems, G.M. Binding of vascular anticoagulant alpha (VAC alpha) to planar phospholipid bilayers. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 4923–4928. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McIlwain, D.R.; Berger, T.; Mak, T.W. Caspase functions in cell death and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riedl, S.J.; Shi, Y. Molecular mechanisms of caspase regulation during apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004, 5, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, M.P.; Zhu, J.Y.; Lawrence, H.R.; Pireddu, R.; Luo, Y.; Alam, R.; Ozcan, S.; Sebti, S.M.; Lawrence, N.J.; Schonbrunn, E. A novel mechanism by which small molecule inhibitors induce the DFG flip in Aurora A. ACS Chem. Biol. 2012, 7, 698–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, B.; Rarey, M.; Lengauer, T. Evaluation of the FLEXX incremental construction algorithm for protein-ligand docking. Proteins 1999, 37, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elkins, J.M.; Santaguida, S.; Musacchio, A.; Knapp, S. Crystal structure of human aurora B in complex with INCENP and VX-680. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 7841–7848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, B.S.; Ahn, S.; Koh, D.; Lee, Y.H.; Shin, S.Y.; Lim, Y. Anticancer and structure-activity relationship evaluation of 3-(naphthalen-2-yl)-N,5-diphenyl-pyrazoline-1-carbothioamide analogs of chalcone. Bioorg. Chem. 2016, 68, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.Y.; Jung, H.; Ahn, S.; Hwang, D.; Yoon, H.; Hyun, J.; Yong, Y.; Cho, H.J.; Koh, D.; Lee, Y.H.; et al. Polyphenols bearing cinnamaldehyde scaffold showing cell growth inhibitory effects on the cisplatin-resistant A2780/Cis ovarian cancer cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014, 22, 1809–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Kim, C.G.; Lim, Y.; Shin, S.Y. Aurora kinase A inhibitor TCS7010 demonstrates pro-apoptotic effect through the unfolded protein response pathway in HCT116 colon cancer cells. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 14, 6571–6577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.Y.; Ahn, S.; Yoon, H.; Jung, H.; Jung, Y.; Koh, D.; Lee, Y.H.; Lim, Y. Colorectal anticancer activities of polymethoxylated 3-naphthyl-5-phenylpyrazoline-carbothioamides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 4301–4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, H.N.; Koh, D.; Lim, Y.; Lee, Y.H.; Shin, S.Y. The synthetic chalcone derivative 2-hydroxy-3′,5,5′-trimethoxychalcone induces unfolded protein response-mediated apoptosis in A549 lung cancer cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 28, 2969–2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Derivatives | Chemical Names | GI50 (μM) | pGI50 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2-(2-fluorophenyl)-3-hydroxy-4H-chromen-4-one/2′-fluoroflavone | 41.19 | 1.39 |

| 2 | 2-(2-fluorophenyl)-3-hydroxy-6-nitro-4H-chromen-4-one/2′-fluoro-6-nitroflavone | 33.52 | 1.47 |

| 3 | 2-(4-fluorophenyl)-3-hydroxy-6-nitro-4H-chromen-4-one/4′-fluoro-6-nitroflavone | 4.49 | 2.35 |

| 4 | 3-hydroxy-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one/4′-methoxyflavone | 37.18 | 1.43 |

| 5 | 3-hydroxy-2-(2-methoxyphenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one/2′-methoxyflavone | 16.44 | 1.78 |

| 6 | 2-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-3-hydroxy-4H-chromen-4-one/3′,4′-dimethoxyflavone | 3.59 | 2.44 |

| 7 | 3-hydroxy-2-(2,4,6-trimethoxyphenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one/2′,4′,6′-trimethoxyflavone | 4.53 | 2.34 |

| 8 | 2-(2,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-3-hydroxy-4H-chromen-4-one/2′,4′-dimethoxyflavone | 21.92 | 1.66 |

| 9 | 2-(6-(4-methoxystyryl)-2,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-3-hydroxy-4H-chromen-4-one/3-hydroxy-2′-(4-methoxystyryl)-flavone | 3.18 | 2.50 |

| 10 | 2-(6-(4-methoxystyryl)-2,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-3-hydroxy-6-nitro-4H-chromen-4-one/3-hydroxy-6-nitro-2′-(4-methoxystyryl)-flavone | 3.63 | 2.44 |

| 11 | 2-(6-(4-methoxystyryl)-2,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-6-bromo-3-hydroxy-4H-chromen-4-one/3-hydroxy-6-bromo-2′-(4-methoxystyryl)-flavone | 2.66 | 2.58 |

| 12 | 2-(6-(4-methoxystyryl)-2,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-7-fluoro-3-hydroxy-4H-chromen-4-one/7-fluoro-3-hydroxy-2′-(4-methoxystyryl)-flavone | 3.07 | 2.51 |

| 13 | 2-(6-(4-methoxystyryl)-2,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-6-chloro-3-hydroxy-4H-chromen-4-one/3-hydroxy-6-chloro-2′-(4-methoxystyryl)-flavone | 2.87 | 2.54 |

| 14 | 2-(6-(4-methoxystyryl)-2,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-6-fluoro-3-hydroxy-4H-chromen-4-one/3-hydroxy-6-fluoro-2′-(4-methoxystyryl)-flavone | 2.41 | 2.62 |

| 15 | 3-hydroxy-2-(naphthalen-1-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one/3-hydroxy-2′,3′-naphthoflavone | 4.14 | 2.38 |

| 16 | 3-hydroxy-6-methoxy-2-(naphthalen-1-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one/3-hydroxy-6-methoxy-2′,3′-naphthoflavone | 7.21 | 2.14 |

| 17 | 3-hydroxy-2-(2-methoxynaphthalen-1-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one/3-hydroxy-6′-methoxy-2′,3′-naphthoflavone | 5.28 | 2.28 |

| 18 | 2-(2,3-dimethoxynaphthalen-1-yl)-3-hydroxy-6-methoxy-4H-chromen-4-one/3-hydroxy-5′,6,6′-trimethoxy-2′,3′-naphthoflavone | 7.51 | 2.12 |

| 19 | 3-hydroxy-2-(4-methoxynaphthalen-1-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one/3-hydroxy-4′-methoxy-2′,3′-naphthoflavone | 4.28 | 2.37 |

| 20 | 3-hydroxy-2-(naphthalen-2-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one/3-hydroxy-3′,4′-naphthoflavone | 2.41 | 2.62 |

| 21 | 3-hydroxy-6-methoxy-2-(naphthalen-2-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one/3-hydroxy-6-methoxy-3′,4′-naphthoflavone | 3.07 | 2.51 |

| 22 | 2-(naphthalen-1-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one/2′,3′-naphthoflavone | 2.91 | 2.54 |

| 23 | 6-methoxy-2-(naphthalen-1-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one/6-methoxy-2′,3′-naphthoflavone | 2.41 | 2.62 |

| 24 | 5-methoxy-2-(naphthalen-1-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one/5-methoxy-2′,3′-naphthoflavone | 7.31 | 2.14 |

| 25 | 6,7-dimethoxy-2-(naphthalen-1-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one/6,7-dimethoxy-2′,3′-naphthoflavone | 3.26 | 2.49 |

| 26 | 7-methoxy-2-(naphthalen-1-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one/7-methoxy-2′,3′-naphthoflavone | 2.56 | 2.59 |

| 27 | 2-(naphthalen-2-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one/3′,4′-naphthoflavone | 29.86 | 1.52 |

| 28 | 6-methoxy-2-(naphthalen-2-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one/6-methoxy-3′,4′-naphthoflavone | 24.39 | 1.61 |

| 29 | 2-(2-methoxynaphthalen-1-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one/2′-methoxy-2′,3′-naphthoflavone | 4.06 | 2.39 |

| 30 | 6-methoxy-2-(2-methoxynaphthalen-1-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one/2′,6-dimethoxy-2′,3′-naphthoflavone | 2.78 | 2.56 |

| 31 | 5-methoxy-2-(2-methoxynaphthalen-1-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one/2′,5-dimethoxy-2′,3′-naphthoflavone | 0.49 | 3.31 |

| 32 | 6,7-dimethoxy-2-(2-methoxynaphthalen-1-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one/2′,6,7-trimethoxy-2′,3′-naphthoflavone | 3.80 | 2.42 |

| 33 | 2-(4-methoxynaphthalen-1-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one/4′-methoxy-2′,3′-naphthoflavone | 20.80 | 1.68 |

| 34 | 5,7-dimethoxy-2-(4-methoxynaphthalen-1-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one/4′,5,7-trimethoxy-2′,3′-naphthoflavone | 21.56 | 1.67 |

| 35 | 7-methoxy-2-(4-methoxynaphthalen-1-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one/4′,7-dimethoxy-2′,3′-naphthoflavone | 18.18 | 1.74 |

| 36 | 2-(2,3-dimethoxynaphthalen-1-yl)-7-methoxy-4H-chromen-4-one/2′,3′,7-trimethoxy-2′,3′-naphthoflavone | 3.95 | 2.40 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shin, S.Y.; Lee, Y.; Kim, B.S.; Lee, J.; Ahn, S.; Koh, D.; Lim, Y.; Lee, Y.H. Inhibitory Effect of Synthetic Flavone Derivatives on Pan-Aurora Kinases: Induction of G2/M Cell-Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis in HCT116 Human Colon Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 4086. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms19124086

Shin SY, Lee Y, Kim BS, Lee J, Ahn S, Koh D, Lim Y, Lee YH. Inhibitory Effect of Synthetic Flavone Derivatives on Pan-Aurora Kinases: Induction of G2/M Cell-Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis in HCT116 Human Colon Cancer Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018; 19(12):4086. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms19124086

Chicago/Turabian StyleShin, Soon Young, Youngshim Lee, Beom Soo Kim, Junho Lee, Seunghyun Ahn, Dongsoo Koh, Yoongho Lim, and Young Han Lee. 2018. "Inhibitory Effect of Synthetic Flavone Derivatives on Pan-Aurora Kinases: Induction of G2/M Cell-Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis in HCT116 Human Colon Cancer Cells" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 19, no. 12: 4086. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms19124086