Fear of Missing Out as a Predictor of Problematic Social Media Use and Phubbing Behavior among Flemish Adolescents

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. FOMO and the Use of Different Social Media Platforms

2.2. FOMO and the Use of More Private versus More Public Social Media Platforms

2.3. FOMO and Problematic Social Media Use (PSMU)

2.4. FOMO and Phubbing

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Breadth of Social Media Platforms Used

3.2.2. Depth of Social Media Platforms Used

3.2.3. Private Versus Public Accessibility of Social Media Platforms Used

3.2.4. Fear of Missing Out (FOMO)

3.2.5. Problematic Social Media Use (PSMU)

3.2.6. Phubbing Behavior

3.2.7. Control variables

3.3. Analyses

4. Results

4.1. Descriptives

4.2. FOMO as a Predictor of the Depth and Breadth of Social Media Use

4.3. FOMO in Relation to the Public Accessibility of Platforms

4.4. FOMO as a Predictor of PSMU and Phubbing Behavior

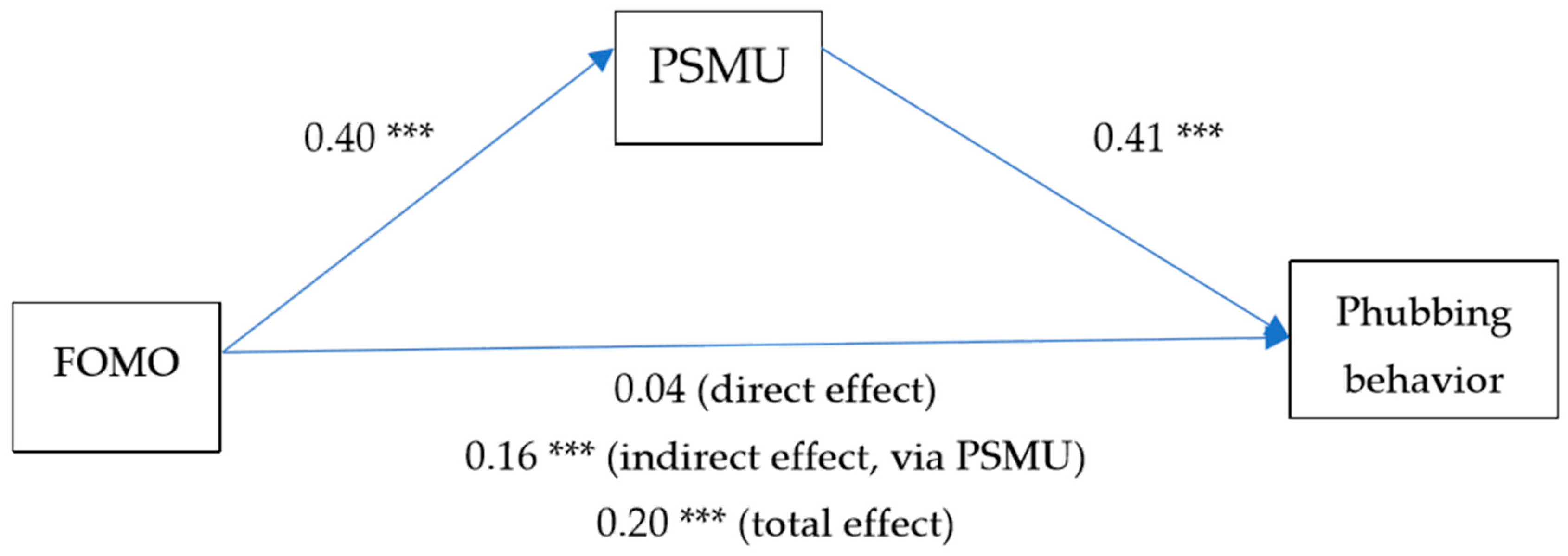

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Items FOMO Scale | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I fear my friends have more rewarding experiences than me | 1 | 0.36 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.26 *** |

| It is important that I understand my friends’ “inside jokes” | 1 | 0.25 *** | 0.21 *** | |

| It bothers me when I miss an opportunity to meet up with friends | 1 | 0.15 *** | ||

| When I go on summer camp or vacation, I continue to keep tabs on what my friends are doing | 1 |

References

- Moreno, M.A.; Jelenchick, L.; Koff, R.; Eikoff, J.; Diermyer, C.; Christakis, D.A. Internet use and multitasking among older adolescents: An experience sampling approach. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 1097–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billieux, J.; Schimmenti, A.; Khazaal, Y.; Maurage, P. Are we overpathologizing everyday life? A tenable blueprint for behavioral addiction research. J. Behav. Addict. 2015, 4, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bean, A.M.; Nielsen, R.K.; Van Rooij, A.J.; Ferguson, C.J. Video game addiction: The push to pathologize video games. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2017, 48, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardefelt-Winther, D.; Heeren, A.; Schimmenti, A.; Van Rooij, A.; Maurage, P.; Carras, M.; Edman, J.; Blaszczynski, A.; Khazaal, Y.; Billieux, J. How can we conceptualize behavioral addiction without pathologizing common behaviours? Addiction 2017, 112, 1709–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Rooij, A.J.; Daneels, R.; Liu, S.; Anrijs, S.; Van Looy, J. Children’s motives to start, continue, and stop playing video games: Confronting popular theories with real-world observations. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2017, 4, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billieux, J. Problematic use of the mobile phone: A literature review and a pathways model. Curr. Psychiatry Rev. 2012, 8, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billieux, J.; Maurage, P.; Lopez-Fernandez, O.; Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D. Can disordered mobile phone use be considered a behavioral addiction? An update on current evidence and a comprehensive model for future research. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2015, 2, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A.K.; Murayama, K.; DeHaan, C.R.; Gladwell, V. Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Oulasvirta, A.; Rattenbury, T.; Ma, L.; Raita, E. Habits make smartphone use more pervasive. Personal Ubiquitous Comput. 2012, 16, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaPlante, D.A.; Nelson, S.E.; Gray, H.M. Breadth and depth involvement: Understanding Internet gambling involvement and its relationship to gambling problems. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2014, 28, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abel, P.J.; Buff, C.L.; Burr, S.A. Social media and fear of missing out: Scale development and assessment. J. Bus. Econ. Res. 2016, 14, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J. Love: Addiction or road to self-realization, a second look. Am. J. Psychoanal. 1982, 42, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivations. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, D.; Ellison, N.B. Social network sites: Definition, history and scholarship. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2008, 13, 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, R.B.; Leshner, G.; Almond, A. The extended iself: The impact of iphone separation on cognition, emotion and physiology. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2015, 20, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, D.J.; Djerf, J.M. High ringxiety: Attachment anxiety predicts experiences of phantom cell phone ringing. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2016, 19, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belk, R.W. Possession and the extended self. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 15, 139–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandor, E.C.; Ferrucci, P.; Duffy, M. Facebook use, envy, and depression among college students: Is facebooking depressing? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 43, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casale, S.; Rugai, L.; Fioravanti, G. Exploring the role of positive metacognitions in explaining the association between the fear of missing out and social media addiction. Addict. Behav. 2018, 85, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, E. Mass communications research and the study of popular culture: An editorial note on a possible future for this journal. Stud. Public Commun. 1959, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, E.; Blumler, J.G. The Uses of Mass Communications: Current Perspectives on Gratifications Research; Sage Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Lee, J.A.; Moon, J.H.; Sung, Y. Pictures speak louder than words: Motivations for using Instagram. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2015, 18, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Abad, N.; Hirsch, C. A two-process view of Facebook use and relatedness need-satisfaction: Disconnection drives us and connection rewards it. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 100, 766–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldon, P.; Bryant, K. Instagram: Motives for its use and relationship to narcissism and contextual age. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 58, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyens, I.; Frison, E.; Eggermont, S. “I don’t want to miss a thing”: Adolescents’ fear of missing out and its relationship to adolescents’ social needs, Facebook use, and Facebook related stress. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 64, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błachnio, A.; Przepiórka, A. Facebook Intrusion, fear of missing out, narcissism, and life satisfaction: A cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 259, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, C.T.; Reiter, S.R.; Anderson, A.C.; Schoessler, M.L.; Sidoti, C.L. “Let me take another selfie”: Further examination of the relation between narcissism, self-perception, and Instagram posts. Psychol. Popul. Media Cult. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, F.; Rahardjo, W.; Tanaya, T.; Qurani, R. Are self-presentation of instagram users influenced by friendship-contingent self-esteem and fear of missing out? Makara Hubs Asia 2017, 21, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, J.B.; Ellison, N.B.; Schoenebeck, S.Y.; Falk, E.B. Sharing the small moments: Ephemeral social interaction on Snapchat. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2016, 19, 956–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhabash, S.; Ma, M. A tale of four platforms: Motivations and uses of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat among college students? Soc. Media Soc. 2017, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, S. Relations among loneliness, social anxiety, and problematic internet use. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2006, 10, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milani, L.; Osualdella, D.; Di Blasio, P. Quality of interpersonal relationships and problematic internet use in adolescents. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 681–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, K.; Basu, D.; Vijaya, K. Internet Addiction: Consensus, Controversies and the Way Ahead. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2010, 20, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, M.D.; Kuss, D.J. Adolescent Social Media Addiction (revised). Educ. Health 2017, 35, 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Buglass, S.L.; Binder, J.F.; Betts, L.R.; Underwood, J.D. Motivators of online vulnerability: The impact of social network sites use and FOMO. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 66, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuster, H.; Chamarro, A.; Oberst, U. Fear of missing out, online social networking and mobile phone addiction: A latent profile approach. Revista de Psicologia Ciències de l’Educació i de l’Esport 2017, 35, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Oberst, U.; Wegmann, E.; Stodt, B.; Brand, M.; Chamarro, A. Negative consequences from heavy social networking in adolescents: The mediating role of fear of missing out. J. Adolesc. 2017, 55, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wegmann, E.; Oberst, U.; Stodt, B.; Brand, M. Online-specific fear of missing out and Internet-use expectancies contribute to symptoms of Internet-communication disorder. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2017, 5, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhai, J.D.; Levine, J.C.; Alghraibeh, A.M.; Alafnan, A.A.; Aldraiweesh, A.A.; Hall, B.J. Fear of missing out: Testing relationships with negative affectivity, online social engagement, and problematic smartphone use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 89, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, H.; Woods, H.C. Fear of missing out and sleep: Cognitive behavioural factors in adolescents’ nighttime social media use. J. Adolesc. 2018, 68, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chotpitayasunondh, V.; Douglas, K.M. How “phubbing” becomes the norm: The antecedents and consequences of snubbing via smartphone. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, M. Cell Phones, College Students, and Conversations: Exploring Mobile Technology Use during Face-to-Face Interactions. Bachelor’s Thesis, The Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vanden Abeele, M.M.V.; Antheunis, M.L.; Schouten, A.P. The effect of mobile messaging during a conversation on impression formation and interaction quality. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofcom. The Communications Market Reports; Ofcom: Warrington, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kuss, D.J.; Kanjo, E.; Rumsey-Crook, M.; Kibowski, F.; Wang, G.Y.; Sumich, A. Problematic mobile phone use and addiction across generations: The roles of psychopathological symptoms and smartphone use. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 2018, 3, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Waeg, S.; D’hanens, K.; Dooms, V.; Naesens, J. Onderzoeksrapport Apestaartjaren 6/Research Report Apestaartjaren 6. Available online: www.apestaartjaren.be/onderzoek/apestaartjaren-6 (accessed on 17 August 2018).

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, N. Uses and Abuses of Coefficient Alpha. Psychol. Assess. 1996, 4, 350–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rooij, A.J.; Ferguson, C.J.; Van de Mheen, D.; Schoenmakers, T.M. Time to abandon Internet Addiction? Predicting problematic Internet, game, and social media use from psychosocial well-being and application use. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2017, 14, 113–121. [Google Scholar]

- Meerkerk, G.; Van den Eijnden, R.J.J.M; Vermulst, A.A.; Garretsen, H.F.L. The Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS): Some psychometric properties. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2009, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meerkerk, G.; Pwned by the Internet. Explorative research into the causes and consequences of compulsive internet use. Ph.D. Thesis, Erasmus University, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R. Generalized ordered logit/partial proportional odds models for ordinal dependent variables. Stata J. 2006, 6, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2013, 38, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiger, J.H. Tests for comparing elements of a correlation matrix. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 87, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.A.; Preacher, K.J. Calculation for the Test of the Difference between Two Dependent Correlations with One Variable in Common (Computer Software). Available online: http://quantpsy.org (accessed on 2 October 2018).

- Allen, I.E.; Seaman, C.A. Likert scales and data analyses. Qual. Prog. 2007, 40, 64–65. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process. Analysis; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, J.; Moreland, J.J. The dark side of social networking sites: An exploration of the relational and psychological stressors associated with Facebook use and affordances. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 45, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T. Cognitive therapy of depression: New perspectives. In Treatment of Depression: Old Controversies and New Approaches; Clayton, P.J., Barrett, J.E., Eds.; Raven Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 265–290. [Google Scholar]

- Orchard, L.J.; Fullwood, C.; Galbraith, N.; Morris, N. Individual differences as predictors of social networking. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2014, 19, 388–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J.D.; Levine, J.C.; Dvorak, R.D.; Hall, B.J. Fear of missing out, need for touch, anxiety and depression are related to problematic smartphone use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, H.; Bibby, P.A. Personality, fear of missing out and problematic internet use and their relationship to subjective well-being. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 76, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A.; David, M.E. My life has become a major distraction from my cell phone: Partner phubbing and relationship satisfaction among romantic partners. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 54, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, R.; Lai, C. Microcoordination 2.0: Social Coordination in the Age of Smartphones and Messaging Apps. J. Commun. 2016, 66, 834–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fear-of-Missing-Out (FOMO) | |||

| Items | M | SD | |

| 1 | I fear my friends have more rewarding experiences than me | 2.33 | 1.11 |

| 2 | It is important that I understand my friends’ “inside jokes” | 3.09 | 1.05 |

| 3 | It bothers me when I miss an opportunity to meet up with friends | 4.16 | 0.90 |

| 4 | When I go on summer camp or vacation, I continue to keep tabs on what my friends are doing | 2.66 | 1.14 |

| Problematic Social Media Use (PSMU) | |||

| Items | M | SD | |

| 1 | How frequently do you find it difficult to quit using social media? | 2.89 | 1.19 |

| 2 | How frequently do others (e.g., your parents or friends) tell you that you should spend less time on social media? | 2.72 | 1.28 |

| 3 | How frequently do you prefer using social media over spending time with others (e.g., with friends or family)? | 1.89 | 0.97 |

| 4 | How frequently do you feel restless, frustrated or irritated when you can’t access social media? | 2.33 | 1.16 |

| 5 | How frequently do you do your homework poorly because you prefer being on social media? | 2.51 | 1.17 |

| 6 | How frequently do you use social media because you feel unhappy? | 2.31 | 1.23 |

| 7 | How frequently do you lack sleep because you spent the night using social media? | 2.44 | 1.35 |

| Phubbing | |||

| Items | M | SD | |

| 1 | How frequently do you use your mobile phone during a conversation in a bar or restaurant? | 2.39 | 0.99 |

| 2 | How frequently are you engaged with your phone during a conversation? | 2.13 | 0.96 |

| 3 | How frequently do you check social media on your phone during a personal conversation? | 1.89 | 0.92 |

| Social Media Platform | N | % of Total Sample | Average Usage Frequency | Less than Once per Week | Once per Week | Multiple Times per Week | Daily | Multiple Times per Day | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | % | % | % | % | % | |||

| 2360 | 89% | 4.49 | 0.87 | 1.4 | 3.6 | 6.4 | 22.2 | 66.5 | |

| Snapchat | 1937 | 73% | 4.36 | 1.00 | 2.4 | 4.5 | 10.1 | 20.5 | 62.5 |

| 1680 | 63% | 4.36 | 0.97 | 1.5 | 4.4 | 15.7 | 31.8 | 46.6 | |

| YouTube | 1596 | 60% | 4.17 | 0.95 | 2.1 | 4.4 | 9.7 | 22.3 | 61.4 |

| Google+ | 925 | 35% | 2.67 | 1.40 | 28.2 | 21.5 | 19.8 | 16.4 | 14.1 |

| 582 | 22% | 3.63 | 1.35 | 8.8 | 14.9 | 19.4 | 18.6 | 38.3 | |

| Swarm | 510 | 19% | 4.26 | 1.09 | 3.7 | 5.5 | 10.8 | 20.6 | 59.4 |

| We Heart It | 329 | 12% | 3.42 | 1.34 | 10.6 | 16.4 | 21.9 | 22.2 | 28.9 |

| 324 | 12% | 2.6 | 1.34 | 28.1 | 21.6 | 24.4 | 14.5 | 11.4 | |

| Tumblr | 298 | 11% | 3.52 | 1.35 | 9.4 | 16.4 | 21.1 | 18.8 | 34.2 |

| Vine | 232 | 9% | 3.12 | 1.38 | 15.9 | 19.8 | 23.3 | 18.5 | 22.4 |

| Foursquare | 172 | 6% | 3.03 | 1.72 | 34.3 | 8.7 | 9.9 | 13.4 | 33.7 |

| Tinder | 120 | 5% | 2.52 | 1.51 | 36.7 | 20 | 15.8 | 9.2 | 18.3 |

| Kiwi | 117 | 4% | 3 | 1.58 | 25.6 | 18.8 | 13.7 | 13.7 | 28.2 |

| Ask.fm | 92 | 3% | 3.6 | 1.60 | 20.7 | 6.5 | 12 | 14.1 | 46.7 |

| Runkeeper | 72 | 3% | 2.17 | 1.10 | 31.9 | 34.7 | 23.6 | 4.2 | 5.6 |

| 60 | 2% | 3.07 | 1.48 | 20 | 20 | 18.3 | 16.7 | 25 | |

| Happening | 48 | 2% | 2.65 | 1.42 | 29.2 | 20.8 | 20.8 | 14.6 | 14.6 |

| Vimeo | 32 | 1% | 2.91 | 1.61 | 34.4 | 6.3 | 15.6 | 21.9 | 21.9 |

| Strava | 25 | 1% | 2.6 | 1.44 | 28 | 28 | 16 | 12 | 16 |

| 24 | 1% | 2.08 | 1.38 | 50 | 16.7 | 20.8 | 12.5 | / | |

| Periscope | 15 | 1% | 3.07 | 1.28 | 13.3 | 20 | 26.7 | 26.7 | 13.3 |

| Endomondo | 11 | 0% | 2.73 | 1.74 | 36.4 | 18.2 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 27.3 |

| Ello | 8 | 0% | 1.5 | 1.41 | 87.5 | / | / | / | 12.5 |

| Meerkat | 6 | 0% | 2.33 | 2.07 | 66.7 | / | / | / | 33.3 |

| Snapchat | Youtube | Google Plus | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | SE | Wald | PE | SE | Wald | PE | SE | Wald | PE | SE | Wald | PE | SE | Wald | PE | SE | Wald | |

| Gender (boy) | −0.50 | 0.09 | 32.55 *** | −0.68 | 0.09 | 52.79 *** | −0.61 | 0.10 | 35.85 *** | 0.72 | 0.10 | 56.21 *** | 0.18 | 0.12 | 2.23 | −0.25 | 0.15 | 2.58 |

| Gender (girl) | a | |||||||||||||||||

| Age | 0.15 | 0.03 | 28.1 *** | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.30 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 14.36 *** | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.14 | −0.09 | 0.04 | 6.42 * | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.15 |

| School track (voc) | 0.41 | 0.14 | 8.72 ** | 0.40 | 0.14 | 8.00 ** | −0.34 | 0.14 | 5.75 * | 0.54 | 0.15 | 13.58 *** | 0.51 | 0.17 | 8.79 ** | 0.36 | 0.25 | 2.18 |

| School track (s-voc) | 0.28 | 0.12 | 5.67 * | 0.35 | 0.12 | 8.88 ** | −0.01 | 0.12 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.15 | 6.84 ** | 0.76 | 0.18 | 19.06 *** |

| School track (ac) | a | |||||||||||||||||

| FOMO | 0.48 | 0.07 | 55.09 *** | 0.28 | 0.07 | 16.89 *** | 0.34 | 0.07 | 22.48 *** | 0.18 | 0.07 | 7.08 ** | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.22 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 2.02 |

| Pearson GOF | X2(1821) = 1635.34, p = 1.00 | X2(1731) = 1842.31, p = 0.031 | X2(1643) = 1716.37, p = 0.102 | X2(1623) = 1621.94, p = 0.503 | X2(1335) = 1370.00, p = 0.247 | X2(1083) = 1131.58, p = 0.148 | ||||||||||||

| −2LL GOF | X2(5) = 150.10, p < 0.001 | X2(5) = 88.07, p < 0.001 | X2(5) = 79.19, p < 0.001 | X2(5) = 75.47, p < 0.001 | X2(5) = 17.20, p = 0.004 | X2(5) = 29.41, p < 0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.05 | ||||||||||||

| Swarm | We Heart It | Tumblr | Vine | Foursquare | Tinder | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | SE | Wald | PE | SE | Wald | PE | SE | Wald | PE | SE | Wald | PE | SE | Wald | PE | SE | Wald | PE | SE | Wald | |

| Gender (boy) | −0.48 | 0.19 | 6.58 ** | −1.41 | 0.58 | 5.87 * | −0.59 | 0.29 | 4.18 * | −0.41 | 0.29 | 2.01 | 0.19 | 0.24 | 0.64 | −0.04 | 0.29 | 0.02 | −0.11 | 0.34 | 0.11 |

| Gender (girl) | a | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Age | 0.21 | 0.06 | 11.25 * | −0.12 | 0.07 | 2.69 | −0.03 | 0.07 | 0.16 | −0.03 | 0.07 | 0.16 | −0.13 | 0.08 | 2.48 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.10 | −0.17 | 0.11 | 2.36 |

| School track (voc) | −0.58 | 0.25 | 5.34 * | 0.65 | 0.31 | 4.36 * | −0.10 | 0.27 | 0.15 | −0.50 | 0.33 | 2.30 | −0.21 | 0.36 | 0.33 | 0.25 | 0.37 | 0.46 | 0.75 | 0.48 | 2.45 |

| School track (s-voc) | 0.36 | 0.22 | 2.78 | 0.01 | 0.24 | 0.00 | −0.17 | 0.25 | 0.43 | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.29 | 0.03 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.93 | 0.48 | 0.42 | 1.33 |

| School track (ac) | a | ||||||||||||||||||||

| FOMO | 0.16 | 0.13 | 1.49 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 2.86 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 1.28 | 0.29 | 0.15 | 3.77 * | 0.37 | 0.18 | 4.22* | 0.47 | 0.21 | 5.26 * | 0.04 | 0.23 | 0.03 |

| Pearson GOF | X2(915) = 856.28, p = 0.917 | X2(571) = 607.49, p = 0.141 | X2(619) = 627.27, p = 0.400 | X2(619) = 620.67, p = 0.474 | X2(599) = 616.26, p = 0.304 | X2(475) = 488.52, p = 0.324 | X2(371) = 373.34, p = 0.456 | ||||||||||||||

| −2LL GOF | X2(5) = 28.53, p < 0.001 | X2(5) = 12.53, p = 0.028 | X2(5) = 6.24, p = 0.283 | X2(5) = 689.76, p = 0.123 | X2(5) = 8.29, p = 0.141 | X2(5) = 7.47, p = 0.188 | X2(5) = 4.26, p = 0.513 | ||||||||||||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | ||||||||||||||

| Pearson’s r | Snapchat | YouTube | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Snapchat | 0.48 *** | 1 | ||

| Youtube | 0.13 *** | 0.04 * | 1 | |

| 0.15 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.18 *** | 1 | |

| FOMO | 0.16 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.00 | 0.06 *** |

| Steiner’s Z (rFOMO, column var vs. rFOMO, row var) | Snapchat | YouTube | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Snapchat | −0.41 | |||

| Youtube | 6.37 *** | 6.38 *** | ||

| 4.18 *** | 4.62 *** | −2.30 * |

| a | b | c | c’ | Indirect Effect Estimate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FOMO (4-item scale) | 0.40 *** | 0.41 *** | 0.04 | 0.20 *** | 0.16 [0.14; 0.19] |

| Individual items | |||||

| I fear my friends have more rewarding experiences than me | 0.21 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.00 | 0.09 *** | 0.09 [0.07; 0.10] |

| It is important that I understand my friends’ “inside jokes” | 0.15 *** | 0.43 *** | −0.01 | 0.05 *** | 0.06 [0.05; 0.08] |

| It bothers me when I miss an opportunity to meet up with friends | 0.05 ** | 0.43*** | −0.04 * | −0.02 | 0.02 [0.00; 0.04] |

| When I go on summer camp or vacation, I continue to keep tabs on what my friends are doing | 0.22 *** | 0.38 *** | 0.09 *** | 0.18*** | 0.09 [0.07; 0.10] |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Franchina, V.; Vanden Abeele, M.; Van Rooij, A.J.; Lo Coco, G.; De Marez, L. Fear of Missing Out as a Predictor of Problematic Social Media Use and Phubbing Behavior among Flemish Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2319. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph15102319

Franchina V, Vanden Abeele M, Van Rooij AJ, Lo Coco G, De Marez L. Fear of Missing Out as a Predictor of Problematic Social Media Use and Phubbing Behavior among Flemish Adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(10):2319. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph15102319

Chicago/Turabian StyleFranchina, Vittoria, Mariek Vanden Abeele, Antonius J. Van Rooij, Gianluca Lo Coco, and Lieven De Marez. 2018. "Fear of Missing Out as a Predictor of Problematic Social Media Use and Phubbing Behavior among Flemish Adolescents" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 10: 2319. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph15102319