Tuberculosis among Full-Time Teachers in Southeast China, 2005–2016

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Data Collection

2.1. Definitions

2.2. Statistical Analysis

2.3. Ethic Statement

3. Results

3.1. Basic Information about Full-Time Teachers with TB

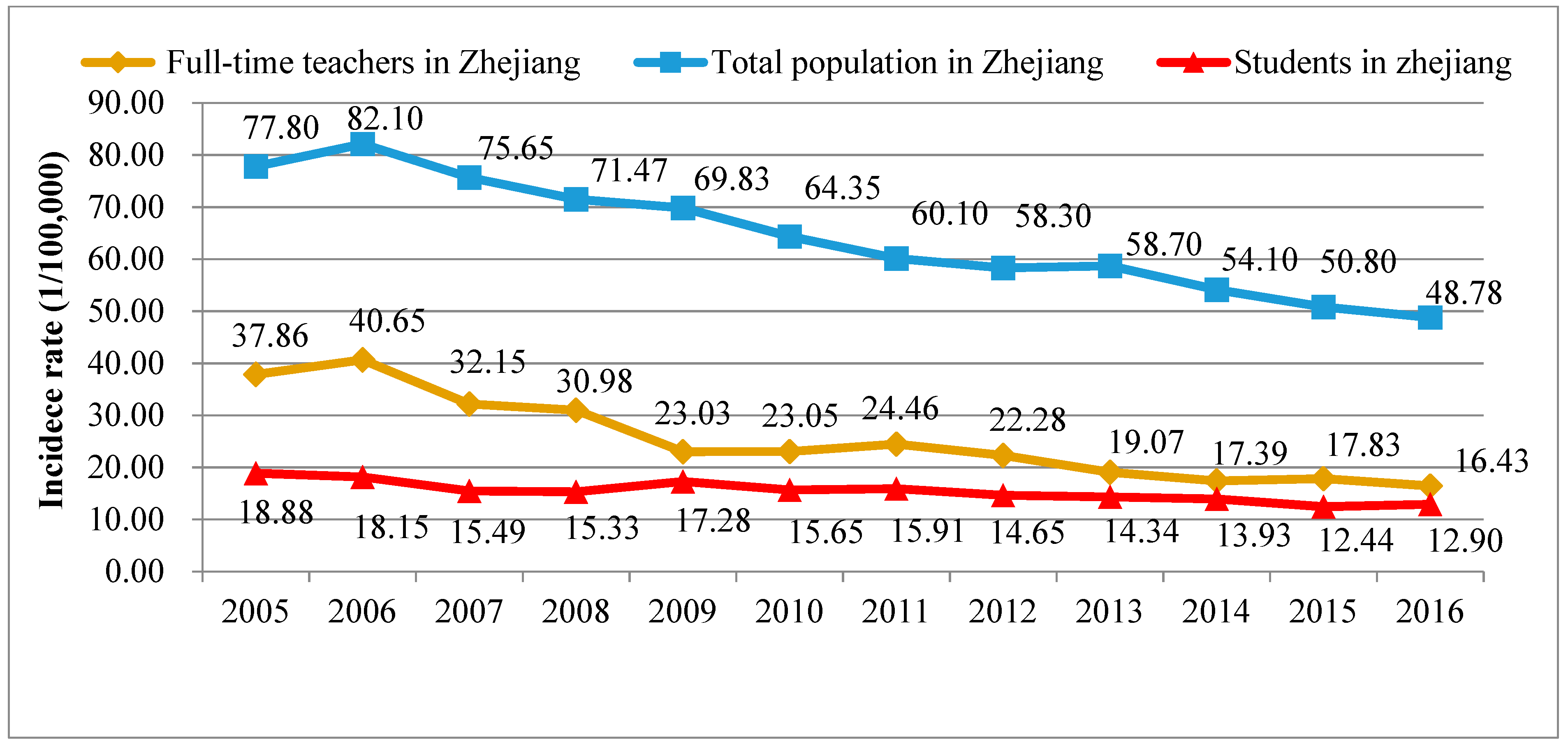

3.2. Epidemiological Trend of the PTB Incidence Rate among Full-Time Teachers

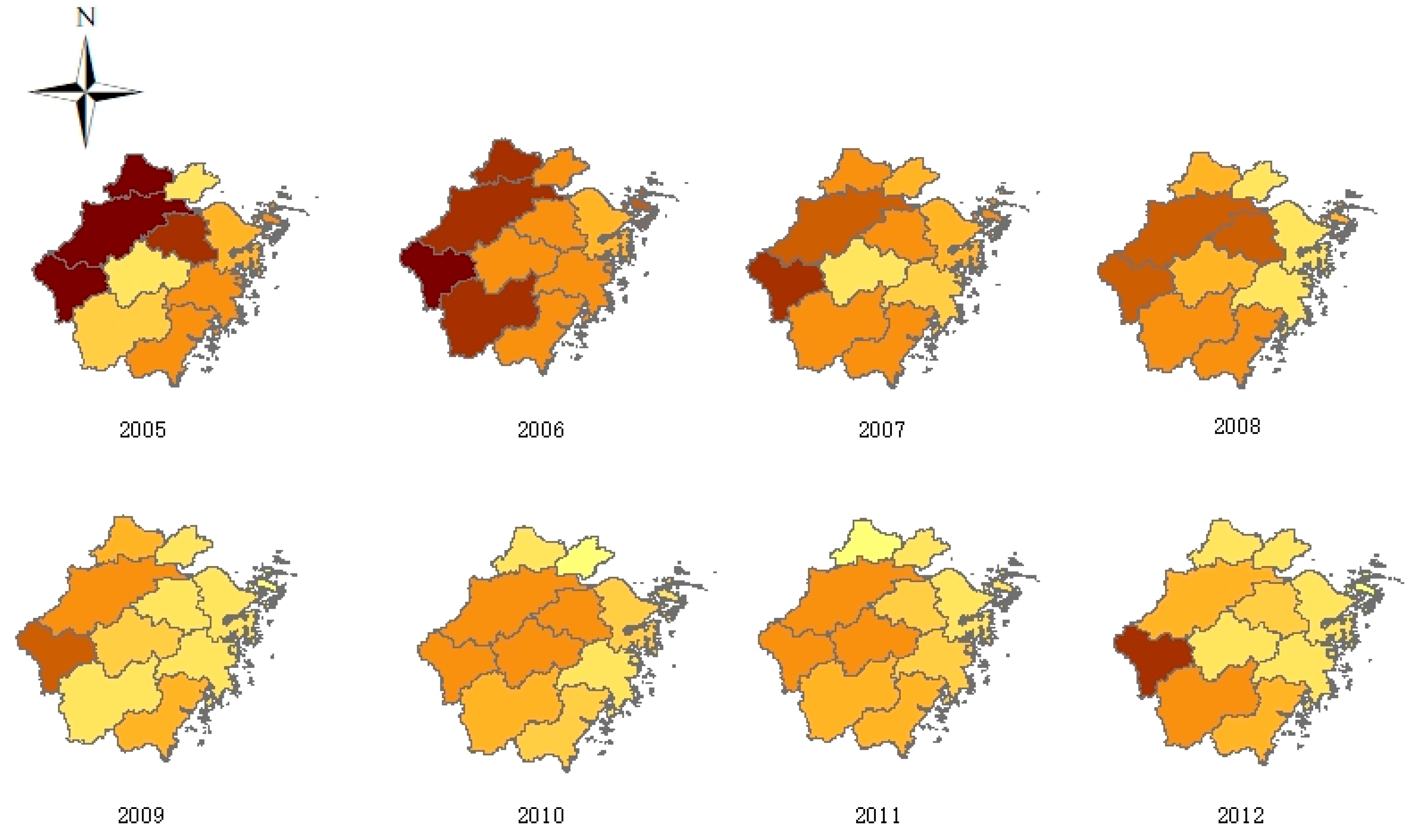

3.3. Geographic Distribution of TB Cases among Full-Time Teachers

3.4. Demographic Characteristics of TB Cases among Full-Time Teachers

3.5. Associations between Clinical Characteristics of TB and Demographic Factors

3.6. Case-Finding Pattern of Full-Time Teachers with TB

3.7. Case-Finding Delay in TB Cases among Full-Time Teachers

3.8. Treatment Outcomes of Full-Time Teachers with TB

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Tuberculosis global facts 2010/2011. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2010, 18, 197. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global Tuberculosis Report 2017. Available online: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/ (accessed on 1 December 2017).

- Li, X.X.; Wang, L.X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.X.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, S.W.; Chen, J.X.; Zhou, X.N. Exploration of ecological factors related to the spatial heterogeneity of tuberculosis prevalence in PR China. Glob. Health Action 2014, 7, 23620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sun, W.; Gong, J.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, Y.; Tan, J.; Ibrahim, A.N.; Zhou, Y. A Spatial, Social and Environmental Study of Tuberculosis in China Using Statistical and GIS Technology. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 1425–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ying, Q.; Chen, K. Spatial distribution patterns of pulmonary tuberculosis incidence in Zhejiang province: Spatial autocorrelation analysis. Chin. J. Public Health 2013, 29, 485–487. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, F.; Cheng, S.; He, G.; Huang, F.; Zhang, H.; Xu, B.; Murimwa, T.C.; Cheng, J.; Hu, D.; Wang, L. Space-time clustering characteristics of tuberculosis in China 2005–2011. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, E.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Wei, X. Spatial and temporal analysis of tuberculosis in Zhejiang Province, China, 2009–2012. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2016, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Wang, X.; Zhong, J.; Chen, S.; Wu, B.; Yeh, H.C.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Gu, H.; Jiang, J. Tuberculosis among healthcare workers in southeastern China: A retrospective study of 7-year surveillance data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 12042–12052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J. Study on Monitoring and Management for Clustering Epidemics of Tubercu losis in Colleges of LiuZhou. Master’s Thesis, Guangxi Medical University, Guangxi, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, T.; Fan, Y.; Li, Y. The experiences of high school students with pulmonary tuberculosis in China: A qualitative study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penin, M.A.; Gomez, J.C.; Lopez, G.L.; Merino, I.V.; Leal, M.B.; de Frias Garcia, E. Tuberculosis outbreak in a school. An. Pediatr. 2007, 67, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Adler-Shohet, F.C.; Low, J.; Carson, M.; Girma, H.; Singh, J. Management of latent tuberculosis infection in child contacts of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2014, 33, 664–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, S.; Chen, S. Tuberculosis among teachers in Wenzhou, 2005–2011. Chin. J. School Health 2014, 35, 141–142. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.K. Tuberculosis in schools in Dongyang, Zhejiang, 2005–2012. Chin. J. Antituberculsois 2013, 35, 939–941. [Google Scholar]

- Education Yearbook of China 2015. Available online: http://www.moe.edu.cn/jyb_sjzl/moe_364/zgjynj_2015/ (accessed on 2 November 2017).

- China Statistical Yearbook. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2017/indexch.htm (accessed on 14 September 2018).

- Belay, M.; Bjune, G.; Ameni, G.; Abebe, F. Diagnostic and treatment delay among Tuberculosis patients in Afar Region, Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Verhagen, L.M.; Kapinga, R.; van Rosmalen-Nooijens, K.A. Factors underlying diagnostic delay in tuberculosis patients in a rural area in Tanzania: A qualitative approach. Infection 2010, 38, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Cao, M.; Mahapatra, T.; Du, X.; Mahapatra, S.; Li, Q.; Feng, L.; Tang, S.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, J. Burden of tuberculosis in Xinjiang between 2011 and 2015: A surveillance data-based study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Z.; Yang, W.; Wang, Y.F. Epidemiological analysis of pulmonary tuberculosis in Heilongjiang province China from 2008 to 2015. Int. J. Mycobacteriology 2017, 6, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, J.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Z.; Hua, Q.; Chen, B.; Gu, H.; Dong, C. Epidemiological characteristics and spatial clusters of pulmonary tuberculosis in Zhejiang province, 2005–2011. Chin. J. Public Health 2016, 32, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, T.; Hua, M.; Zhang, Y. Study on Overall Features and Spatial Evolution of County Economy—A Case of Zhejiang Province. Econ. Geogr. 2014, 34, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Kwaku, A.B.; Chen, Y.; Xin, H.; Tan, H.; Shi, W.W. Gender and regional disparities of tuberculosis in Hunan, China. Int. J. Equity Health 2014, 13, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, S.; Jiang, H.; Xiong, J.; Wang, Y.; Ou, M.; Cai, J.; Yang, C.; Wang, Z.; Ge, S.; et al. The prevalence of latent tuberculosis infection in rural Jiangsu, China. Public Health 2017, 146, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellini, I.; Pugi, S.; Degl’Innocenti, C.; Roselli, A.; Biagiotti, D.; Paliaga, L.; Berti, C.; Margheri, V.; Ricci, L.; Nastasi, A. Tuberculosis in Prato (Tuscany Region, Central Italy) in the period 2007–2014. Epidemiol. Prev. 2017, 41, 256–260. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Standards and Regulations for the Physical Examination of the Qualifications of Primary and Secondary School Teachers in Zhejiang Province. Available online: http://www.jszg.edu.cn/portal/resource_downloads/index (accessed on 25 December 2010).

- Raviglione, M.; Director, G.T. Global Strategy and Targets for Tuberculosis Prevention, Care and Control after 2015; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lönnroth, K.; Castro, K.G.; Chakaya, J.M.; Chauhan, L.S.; Floyd, K.; Glaziou, P.; Raviglione, M.C. Tuberculosis control and elimination 2010–2050: Cure, care, and social development. Lancet 2010, 375, 1814–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreeramareddy, C.T.; Panduru, K.V.; Menten, J.; Van den Ende, J. Time delays in diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis: A systematic review of literature. BMC Infect. Dis. 2009, 9, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Needham, D.M.; Foster, S.D.; Tomlinson, G.; Godfrey-Faussett, P. Socio-economic, gender and health services factors affecting diagnostic delay for tuberculosis patients in urban Zambia. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2001, 6, 256–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Godfreyfaussett, P.; Kaunda, H.; Kamanga, J.; Van Beers, S.; Van Cleeff, M.; Kumwenda-Phiri, R.; Tihont, V. Why do patients with a cough delay seeking care at Lusaka urban health centres? A health systems research approach. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2002, 6, 796–805. [Google Scholar]

- Cruzferro, E.; Ursúadíaz, M.I.; Taboadarodríguez, J.A.; Hervadavidal, X.; Anibarro, L.; Túñez, V. Epidemiology of tuberculosis in Galicia, Spain, 16 years after the launch of the Galician tuberculosis programme. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2014, 18, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, L.; Xiao, S. Factors associated with diagnostic delay for patients with smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis in rural Hunan, China. Chin. J. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 2004, 27, 617–620. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.C.; Chen-Yuan, C.; Pan, S.C.; Wang, J.Y.; Lin, H.H. Health system delay among patients with tuberculosis in Taiwan: 2003–2010. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Han, C.; Chang, K.F.; Wang, M.S.; Huang, T.R. Total delay in treatment among tuberculous meningitis patients in China: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Yang, M.; Xu, M.; Ding, C.; Li, Y.; Xu, K.; Shen, J.; Li, L. Diagnostic delay and mortality of active tuberculosis in patients after kidney transplantation in a tertiary care hospital in China. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Wang, X.; Zhong, J.; Chen, B.; Huang, Y. Factors associated with diagnostic delay for primary pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Zhejiang province. Chin. J. Public Health 2013, 4, 481–484. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X. Study on the Norm of Occupational Stress and its Health Effects among Primary and Middle School Teachers in Nanchang City. Master’s Thesis, Nanchang University Medical College, Nanchang, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Atif, M.; Anwar, Z.; Fatima, R.K.; Malik, I.; Asghar, S.; Scahill, S. Analysis of tuberculosis treatment outcomes among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Bahawalpur, Pakistan. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Wang, X.; Gu, H.; Zhong, J.; Chen, S. Influencing factors of case-finding delay among student pulmonary TB patients in Zhejiang Province. Chin. J. Sch. Health 2013, 34, 1339–1341. [Google Scholar]

- Maimaiti, R.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, K.; Mijiti, P.; Wubili, M.; Musa, M.; Andersson, R. High prevalence and low cure rate of tuberculosis among patients with HIV in Xinjiang, China. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dememew, Z.G.; Habte, D.; Melese, M.; Hamusse, S.D.; Nigussie, G.; Hiruy, N.; Girma, B.; Kassie, Y.; Haile, Y.K.; Jerene, D.; et al. Trends in tuberculosis case notification and treatment outcomes after interventions in 10 zones of Ethiopia. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2016, 20, 1192–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, L.M.; Harter, J.; Tomberg, J.O.; Vieira, D.A.; Antunes, M.L.; Cardozo-Gonzales, R.I. Monitoring and assessment of outcome in cases of tuberculosis in a municipality of Southern Brazil. Rev. Gaucha Enferm. 2016, 37, e51467. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Du, J.; Liu, C.; Ma, Y.; Jiang, X.; Xu, X.; Wang, X. Clinical analysis of adverse reactions to anti-tuberculosis treatment in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. J. Pathog. Biol. 2014, 15, 1121–1125. [Google Scholar]

- Kant, S.; Singh, A.K.; Parmeshwaran, G.G.; Haldar, P.; Malhotra, S.; Kaur, R. Delay in initiation of treatment after diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in primary health care setting: Eight year cohort analysis from district Faridabad, Haryana, North India. Rural Remote Health 2017, 17, 4158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javaid, A.; Hasan, R.; Zafar, A.; Chaudry, M.A.; Qayyum, S.; Qadeer, E.; Shaheen, Z.; Agha, N.; Rizvi, N.; Afridi, M.Z.; et al. Pattern of first- and second-line drug resistance among pulmonary tuberculosis retreatment cases in Pakistan. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2017, 21, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.; Melendeztorres, G.J. Systematic review of risk factors for nonadherence to TB treatment in immigrant populations. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2016, 110, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Index | Case-Finding Delay | x2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 324 (37.90) | 531 (62.10) | 0.12 | 0.74 |

| Female | 332 (37.10) | 562 (62.90) | ||

| Age | ||||

| <30 | 177 (30.70) | 399 (69.30) | 25.65 | <0.01 ** |

| 30–39 | 179 (37.60) | 297 (62.40) | ||

| 40–49 | 107 (37.90) | 175 (62.10) | ||

| 50–59 | 120 (46.50) | 138 (53.50) | ||

| ≥60 | 73 (46.50) | 84 (53.50) | ||

| Habitation | ||||

| Local | 607 (36.90) | 1039 (63.10) | 4.73 | 0.03 * |

| Not local | 49 (47.60) | 54 (52.40) | ||

| Onset time of symptoms | ||||

| First quarter | 176 (42.40) | 239 (57.60) | 5.94 | 0.11 |

| Second quarter | 175 (37.00) | 298 (63.00) | ||

| Third quarter | 152 (35.80) | 273 (64.20) | ||

| Fourth quarter | 153 (35.10) | 283 (64.90) | ||

| Treatment classification | ||||

| Initial treatment | 598 (36.40) | 1045 (63.60) | 14.26 | <0.01 ** |

| Retreatment | 58 (54.70) | 48 (45.30) | ||

| Case-finding patterns | ||||

| Direct visit to designated TB hospital | 308 (37.10) | 523 (62.90) | 6.16 | 0.05 * |

| Referrals or tracking | 336 (38.90) | 528 (61.10) | ||

| Physical examination | 12 (22.20) | 42 (77.80) | ||

| Diagnostic result | ||||

| Pulmonary tuberculosis | 558 (36.70) | 963 (63.30) | 6.10 | 0.05 * |

| Tuberculous pleurisy | 49 (38.30) | 79 (61.70) | ||

| Extra-pulmonary tuberculosis | 49 (49.00) | 51 (51.00) | ||

| Index | B | OR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| ≤35 | -- | 1 | -- |

| >35 | 0.37 | 1.44 (1.18, 1.76) | <0.01 ** |

| Habitation | |||

| Local | -- | 1 | -- |

| Not local | 0.60 | 1.81 (1.20, 2.73) | <0.01 * |

| Treatment classification | |||

| Initial treatment | -- | 1 | -- |

| Retreatment | 0.73 | 2.06 (1.39, 3.08) | <0.01 ** |

| Case-finding patterns | |||

| Physical examination | -- | 1 | -- |

| Direct visit to designated TB hospital | 0.69 | 2.00 (1.03, 3.88) | 0.04 * |

| Referrals or tracking | 0.81 | 2.26 (1.16, 4.38) | 0.02 * |

| Diagnostic result | |||

| Pulmonary tuberculosis | -- | 1 | -- |

| Tuberculous pleurisy | 0.05 | 1.05 (0.72, 1.53) | 0.79 |

| Extra-pulmonary tuberculosis | 0.54 | 1.71 (1.13, 2.61) | 0.01 ** |

| Index | Treatment Outcome | x2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cure | Adverse Outcomes | |||

| Age | ||||

| <30 | 481 (81.94) | 106 (10.06) | 20.71 | <0.01 ** |

| 30–39 | 384 (78.21) | 107 (21.79) | ||

| 40–49 | 212 (74.39) | 73 (25.61) | ||

| 50–59 | 195 (73.58) | 70 (26.42) | ||

| ≥60 | 112 (67.07) | 55 (32.93) | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 666 (76.20) | 208 (23.80) | 0.78 | 0.38 |

| Female | 718 (78.00) | 203 (22.00) | ||

| Habitation | ||||

| Local | 1299 (76.80) | 393 (23.20) | 1.82 | 0.18 |

| Not local | 85 (82.50) | 18 (17.50) | ||

| Case-finding patterns | ||||

| Clinical consultation | 592 (68.40) | 273 (31.60) | 71.42 | <0.01 ** |

| Referrals and tracking | 748 (85.40) | 128 (14.60) | ||

| Physical examination | 44 (81.50) | 10 (18.50) | ||

| Case-finding delay | ||||

| Yes | 517 (78.80) | 139 (21.20) | 0.01 | 0.94 |

| No | 863 (79.00) | 230 (21.00) | ||

| Result of sputum | ||||

| Smear positive | 357 (81.50) | 81 (18.50) | 0.95 | 0.33 |

| Smear negative | 889 (79.30) | 232 (20.70) | ||

| Diagnostic result | ||||

| Pulmonary tuberculosis | 1246 (79.92) | 313 (20.08) | 82.83 | <0.01 ** |

| Tuberculous pleurisy | 94 (71.76) | 37 (28.24) | ||

| Extra-pulmonary tuberculosis and others | 44 (41.90) | 61 (58.10) | ||

| Treatment classification | ||||

| Initial treatment | 1313 (77.88) | 373 (22.12) | 9.41 | <0.01 ** |

| Retreatment | 71 (65.14) | 38 (34.86) | ||

| Strategy of patient management | ||||

| Full-course supervision | 1338 (91.50) | 124 (8.50) | 927.62 | <0.01 ** |

| Self-administration or other | 46 (13.80) | 287 (86.20) | ||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bao, H.; Liu, K.; Wu, Z.; Chai, C.; He, T.; Wang, W.; Wang, F.; Peng, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, B.; et al. Tuberculosis among Full-Time Teachers in Southeast China, 2005–2016. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2024. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph15092024

Bao H, Liu K, Wu Z, Chai C, He T, Wang W, Wang F, Peng Y, Wang X, Chen B, et al. Tuberculosis among Full-Time Teachers in Southeast China, 2005–2016. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(9):2024. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph15092024

Chicago/Turabian StyleBao, Hongdan, Kui Liu, Zikang Wu, Chengliang Chai, Tieniu He, Wei Wang, Fei Wang, Ying Peng, Xiaomeng Wang, Bin Chen, and et al. 2018. "Tuberculosis among Full-Time Teachers in Southeast China, 2005–2016" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 9: 2024. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph15092024