Domestic Violence During Pregnancy in Greece

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Prevalence of IPV in Greece

1.2. Global Prevalence of IPV in Pregnancy

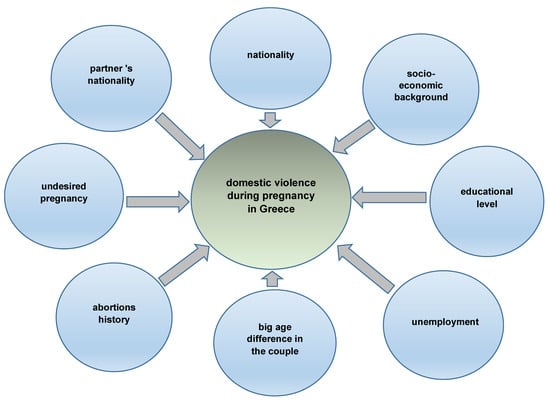

1.3. IPV in Pregnancy: Risk Factors

1.4. Consequences of IPV in Pregnancy

2. Methodology

Study Design, Data, and Sampling

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of IPV in Pregnancy

3.2. Factors Associated with High Risk of IPV Pregnancy

3.3. Action Taken

4. Discussion

5. Strength and Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Council of Europe. Recommendation Rec (2002) 5 of the Committee of Ministers to Member States on the Protection of Women against Violence Adopted on 30 April 2002 and Explanatory Memorandum. Available online: https://www.euromed-justice.eu/en/system/files/20090508132109_CouncilofEurope.RecommendationRec%282002%295ontheCommitteeofMinisters.protectionofwomen.Coe_.2002.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- World Health Organization. Understanding and Addressing Violence against Women. 2012. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/77432/WHO_RHR_12.36_eng.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- Artinopoulou, V.; Farsedakis, J. Domestic Violence against Women: The First Epidemiological Research in Greece. 2003. Available online: https://kethi.gr/wp-content/uploads/2009/01/111_ENDO-OIKOGENEIAKH_BIA_KATA_GYNAIKWN.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- Tsouderou, I. Intimate Partner Violence and Women’s Legal Protection; Παρασκήνιο: Athens, Greece, 2009; ISBN 960-8342-73-2. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Papadakaki, M.; Tzamalouka, G.S.; Chatzifotiou, S.; Chliaoutakis, J. Seeking for Risk Factors of Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) in a Greek National Sample the Role of Self-Esteem. J. Interpers. Violence 2009, 24, 732–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tailleu, T.L.; Brownridge, D.A. Violence Against Pregnant Women: Prevalence, Patterns, Risk Factors, Theories, and Directions for Future Research. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2010, 15, 14–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazmararian, J.A.; Lazorick, S.; Spitz, A.M.; Ballard, T.J.; Saltzman, L.E.; Marks, J.S. Prevalence of violence against pregnant women. JAMA 1996, 275, 1915–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berenson, A.B.; San Miguel, V.; Wilkinson, G.S. Prevalence of physical and sexual assault in pregnant adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 1992, 13, 446–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenson, A.B.; Stiglich, N.J.; Wilkinson, G.S.; Anderson, G.D. Drug abuse and other risk factors for physical abuse in pregnancy among white non-Hispanic, Black, and Hispanic women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1991, 164, 1491–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazmararian, J.A.; Adams, M.M.; Saltzman, L.E.; Johnson, C.H.; Bruce, F.C.; Marks, J.S. The relationship between pregnancy intendedness and physical violence in mothers of newborns. Obstet. Gynecol. 1995, 85, 1031–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, B.; McFarlane, J.; Soeken, K. Abuse during pregnancy: Effects on maternal complication and birth weight in adult and teenage women. Obstet Gynecol. 1994, 84, 323–328. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, D.; Cecutti, A. Physical abuse in pregnancy. CMAJ 1993, 149, 1257–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.; Sweett, S.; Stoltz, T.A. Domestic violence in pregnancy: A prevalence study. Med. J. Aust. 1994, 161, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, A.; Stewart, D.E. Maternal and fetal outcomes of intimate partner violence associated with pregnancy in the Latin American and Caribbean region. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2014, 124, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamu, S.; Abrahams, N.; Temmerman, M.; Musekiwa, A.; Zarowsky, C. A Systematic Review of African Studies on Intimate Partner Violence against Pregnant Women: Prevalence and Risk Factors. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacchus, L.; Mezey, G.; Bewley, S. Domestic violence: Prevalence in pregnant women and associations with physical and psychological health. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2004, 113, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Olavarrieta, C.; Paz, F.; Abuabarak, K.; Martínez-Ayala, H.B.; Kolstad, K.; Palermo, T. Abuse during pregnancy in Mexico City. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2007, 97, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, L.L.; Oths, K.S. Prenatal predictors of intimate partner violence. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2004, 33, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heaman, M.I. Relationships between physical abuse during pregnancy and risk factors for preterm birth among women in Manitoba. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2005, 34, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.K.; Haider, F.; Ellis, K.; Hay, D.M.; Lindow, S.W. The prevalence of domestic violence in pregnant women. BJOG 2003, 110, 272–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltzman, L.E.; Johnson, C.H.; Gilbert, B.C.; Goodwin, M.M. Physical abuse around the time of pregnancy: An examination of prevalence and risk factors in 16 states. Matern. Child Health J. 2003, 7, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thananowan, N.; Heidrich, S.M. Intimate partner violence among pregnant Thai women. Violence Against Women 2008, 15, 509–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, J. Cross-cultural differences in physical aggression between partners: A social- role analysis. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 10, 13353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunnicutt, G. Varieties of patriarchy and violence against women: Resurrecting ‘patriarchy’ as a theoretical tool. Violence Against Women 2009, 15, 553–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.L.; Mackie, L.; Kupper, L.L.; Buescher, P.A.; Moracco, K.E. Physical abuse of women before, during, and after pregnancy. JAMA 2001, 285, 1581–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipsky, S.; Holt, V.L.; Easterling, T.R.; Critchlow, C.W. Police-reported intimate partner violence during pregnancy: Who is at risk? Violence Vict. 2005, 20, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, B.A.; Daugherty, R.A. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: Incidence and associated health behaviors in a rural population. Matern. Child Health J. 2007, 11, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bullock, L.; Mears, J.; Woodcock, C.; Record, R. Retrospective study of the association of stress and smoking during pregnancy in rural women. Addict. Behav. 2001, 26, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datner, E.M.; Wiebe, D.J.; Brensinger, C.M.; Nelson, D.B. Identifying pregnant women experiencing domestic violence in an urban emergency department. J. Interpers. Violence 2007, 22, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, M.R.; Martin, S.L.; Morocco, K.E. Homicide risk factors among pregnant women abused by their partners: Who leaves the perpetrator and who stays? Violence Against Women 2004, 10, 498–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cripe, S.M.; Sanchez, S.E.; Perales, M.T.; Lam, N.; Garcia, P.; Williams, M.A. Association of intimate partner physical and sexual violence with unintended pregnancy among pregnant women in Peru. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2008, 100, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Paterson, J.; Carter, S.; Iusitini, L. Intimate partner violence and unplanned pregnancy in the Pacific Islands Families Study. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2008, 100, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, L.E.; Cabral, H.; Amaro, H.; Aschengrau, A. Lifetime and during pregnancy experience of violence and the risk of low birth weight and preterm birth. J. Midwifery Women Health 2008, 53, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Violence against Women. Health Consequences. July 1997. Available online: http://www.who.int/gender/violence/en/v8.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- Beckmann, C.; Ling, F.; Laube, D.; Smith, R.; Barzansky, B.; Herbert, W. Premature Rupture of Membranes, Obstetrics and Gynecology; Lippincott Williams and Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, S.L.; Li, Y.; Casanueva, C.; Harris-Britt, A.; Kupper, L.L.; Cloutier, S. Intimate partner violence and women’s depression before and during pregnancy. Violence Against Women 2006, 12, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedin, L.W.; Janson, P.O. Domestic violence during pregnancy. The prevalence of physical injuries, substance use, abortions and miscarriages. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2000, 79, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFarlane, J.; Parker, B.; Soeken, K. Physical abuse, smoking, and substance use during pregnancy: Prevalence, interrelationships, and effects on birth weight. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 1996, 25, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quelopana, A.M.; Champion, J.D.; Salazar, B.C. Health behavior in Mexican pregnant women with a history of violence. West J. Nurs. Res. 2008, 30, 1005–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFarlane, J.; Parker, B.; Soeken, K.; Bullock, L. Assessing for abuse during pregnancy. Severity and frequency of injuries and associated entry into prenatal care. JAMA 1992, 267, 3176–3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherin, K.M.; Sinacore, J.M.; Li, X.Q.; Zitter, R.E.; Shakil, A. HITS: A short domestic violence screening tool for use in a family practice setting. Fam. Med. 1998, 30, 508–512. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky, S.; Caetano, R. Impact of Intimate Partner Violence on Unmet Need for Mental Health Care: Results from the NSDUH. Psychiatr. Serv. 2007, 58, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, D.; Soares, J.; Lindert, J.; Hatzidimitriadou, E.; Karlsso, A.; Sundin, Ö.; Toth, O.; Ioannidi-Kapolou, E.; Degomme, O.; Cervilla, J.; et al. Intimate partner violence in Europe: Design and methods of a multinational study. Gac. Sanit. 2013, 27, 558–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelens, K.; Verstraelen, H.; Van Egmont, K.; Temmerman, M. Disclosure and health-seeking behaviour following intimate partner violence before and during pregnancy in Flanders, Belgium: A survey surveillance study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2007, 137, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyroudi, A.; Flora, K. Meaning Attribution to Intimate Partner Violence by Counselors Who Support Women with Intimate Partner Violence Experiences in Greece. J. Interpers. Violence 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Injuries & Violence Characteristics | F | % |

|---|---|---|

| Abused in Pregnancy | ||

| Yes | 33 | 6.0% |

| Abused Since the Beginning of Pregnancy | ||

| Yes | 18 | 3.4% |

| Most Frequent Part of Injury | ||

| Face | 17 | 3.1% |

| Head | 4 | 0.7% |

| Breast | 3 | 0.5% |

| Back | 3 | 0.5% |

| Upper Limbs | 5 | 0.9% |

| Lower Limbs | 1 | 0.2% |

| Hips | 2 | 0.4% |

| Abdomen | 7 | 1.3% |

| Other | 1 | 0.2% |

| Means of Violence | ||

| Slapping or pushing | 15 | 2.7% |

| Punching, kicking etc. | 8 | 1.5% |

| Internal, permanent injury to head | 1 | 0.2% |

| Use of weapon | 1 | 0.2% |

| Threat | 1 | 0.2% |

| Are You Afraid of Your Partner or Someone Else? | ||

| Yes | 13 | 2.8% |

| Were You Forced to Intercourse in the Previous Year? | ||

| Yes | 9 | 1.9 |

| Factor | Non-Abused | Abused | Total | p-Value 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Nationality | 0.001 | ||||||

| Greek | 385 | 94.80% | 21 | 5.20% | 406 | 100.00% | |

| Other | 55 | 81.10% | 12 | 17.90% | 67 | 100.00% | |

| Partner’s nationality | 0.002 | ||||||

| Greek | 397 | 94.50% | 23 | 5.50% | 420 | 100.00% | |

| Other | 43 | 81.10% | 10 | 18.90% | 53 | 100.00% | |

| Education level | 0.008 | ||||||

| Elementary school–junior high school | 17 | 85.00% | 3 | 15.00% | 20 | 100.00% | |

| Senior high school | 122 | 93.10% | 9 | 6.90% | 131 | 100.00% | |

| University | 173 | 95.60% | 8 | 4.40% | 181 | 100.00% | |

| Master’s degree–doctorate | 71 | 98.60% | 1 | 1.40% | 72 | 100.00% | |

| Profession (Greek) | 0.0001 | ||||||

| Housewife | 39 | 92.90% | 3 | 7.10% | 42 | 100.00% | |

| Unemployed | 22 | 84.60% | 4 | 15.40% | 26 | 100.00% | |

| University student | 8 | 80.00% | 2 | 20.00% | 10 | 100.00% | |

| Civil servant | 114 | 98.30% | 2 | 1.70% | 116 | 100.00% | |

| Private employee | 144 | 94.70% | 8 | 5.30% | 152 | 100.00% | |

| Self-employed | 41 | 100.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 41 | 100.00% | |

| Other | 15 | 88.20% | 2 | 11.80% | 17 | 100.00% | |

| Marital status | 0.003 | ||||||

| Married | 27 | 75.00% | 9 | 25.00% | 36 | 100.00% | |

| Single | 408 | 94.70% | 23 | 5.30% | 431 | 100.00% | |

| Separated | 1 | 100.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 100.00% | |

| Divorced | 6 | 85.70% | 1 | 14.30% | 7 | 100.00% | |

| Age | 0.788 | ||||||

| 16–25 | 58 | 90.60% | 6 | 9.40% | 64 | 100.00% | |

| 26–35 | 304 | 93.30% | 22 | 6.70% | 326 | 100.00% | |

| 36–45 | 73 | 93.60%% | 5 | 6.40% | 78 | 100.00% | |

| Abortion | 0.024 | ||||||

| No | 342 | 94.70% | 19 | 5.30% | 361 | 100.00% | |

| Yes | 88 | 88.00% | 12 | 12.00% | 100 | 100.00% | |

| Partner’s agreement | 0.003 | ||||||

| No | 7 | 63.60% | 4 | 36.40% | 11 | 100.00% | |

| Yes | 427 | 94.50% | 25 | 5.50% | 452 | 100.00% | |

| Performed proposed tests | 0.000 | ||||||

| No | 10 | 45.50% | 12 | 54.50% | 22 | 100.00% | |

| Yes | 432 | 95.40% | 21 | 4.60% | 453 | 100.00% | |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Antoniou, E.; Iatrakis, G. Domestic Violence During Pregnancy in Greece. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4222. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph16214222

Antoniou E, Iatrakis G. Domestic Violence During Pregnancy in Greece. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(21):4222. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph16214222

Chicago/Turabian StyleAntoniou, Evangelia, and Georgios Iatrakis. 2019. "Domestic Violence During Pregnancy in Greece" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 21: 4222. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph16214222