Hospital Medical and Nursing Managers’ Perspective on the Mental Stressors of Employees

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Recruitment

2.3. Design of Interview

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Sample

3. Results

3.1. Managers’ Perspective on the Influence of Work Task on the Employees

3.1.1. Emotional Demands

‘When we had or have a critical patient on the ward and we see this success, that we have mobilized him regularly, that we have taken time for him, this, there is no need to say much, no staff, little time. But because we still wrested the time from somewhere, we mobilized the patient regularly. And we simply see that the patient is on the road to recovery. And that is just, it was worth it’.(SN 24)

‘I have seen a colleague coming out of the patient’s room, a young patient died, died alone, that is the worst, and she came out crying’.(SN 16)

‘This can sometimes be a traumatic experience with a dying patient, the first death certificate, the first post-mortem that you have to do’.(CP 9)

‘In other words, to the point of employees being personally threatened and not always daring to go into the underground car park when they go home at 9 p.m.’(CP 9)

‘So, because you know of course that you could do it better, but I only have two hands and I can’t help it. I have to leave one of them suffering’.(SP 35)

‘Explantations, i.e., the removal of organs from patients, are certainly such a stressful situation, … and when you’re about to turn off some equipment, it’s things like that’.(CP 2)

3.1.2. Responsibility

‘A patient who is called for a clarification discussion but who comes with a caregiver, cannot be clarified in essential points’.(CP 1)

3.1.3. Decision Latitude

‘For example, the employees can already participate in the work scheduling and simply enter the yes, the needed free times or of course vacation’.(SN 22)

‘I would never hire anyone either, so everybody has a say in that. I would never hire someone where the assistants say, no, it doesn’t fit at all, then we do not hire this person’.(CP 15)

‘When I have called everybody and they all say, “I don’t have time”, then I get the order that one has to come, even though he said he would not come. So, I sort of sign someone up for duty on their day off’.(SN 18)

3.1.4. Qualification

‘The employees have not had as good or sufficient time for familiarization. They are practically thrown in at the deep end, so to speak’.(CP 6)

‘they are guided very closely and patients are cared for together with them’.(CP 10)

3.1.5. Information Offer

‘For example, you do not know whether a patient is being cared for or not. Whether a patient is ambulatory or not.”…” Nevertheless, it is regularly the case that we run after information’.(CP 1)

‘The communication channel is also regulated by the distribution via e-mail account. Everyone has an e-mail account; everyone is obliged to check his e-mails on a daily basis. So that also the information, if the employees are there, then also flow. ”…” On the other hand, there is also further training, which we always do. We have meetings in the morning, where we discuss these topics’.(CP 2)

3.1.6. Variability/Diversity of the Task

‘And now, simply because the employee key has become less, it happens that everyone has to do and has be able to do everything. And some people still have difficulties with things. That is, that they still have problems implementing what is demanded of them’.(SN 23)

‘I believe that the spectrum of what we offer here in our department—medical, internal medicine, cardiology—is very, very wide’.(SP 33)

3.1.7. Completeness of the Task

‘We have no rest. That’s what I said before, no rest, as I said, in order to completely carry out a thing from A to Z according to a pattern. You have to be flexible all the time. As I said before, that is the thing that, as I said before, puts such a strain on us’.(SN 24)

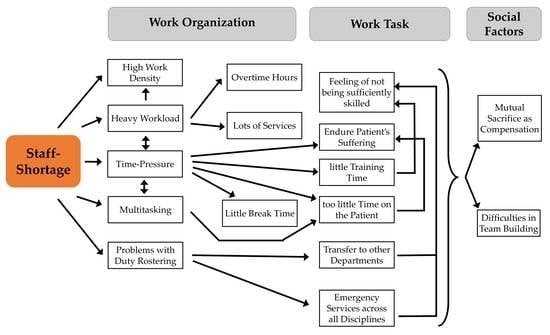

3.2. Managers’ Perspective on the Influence of Work Organization on the Employees

3.2.1. Work Process

‘The greatest burden, I would really say, the constant understaffing’.(SN 26)

‘Workload, that sometimes you cannot meet the patients’ needs due to lack of personnel’(SN 17)

‘I guess one of the major burdens is just the amount of work’.(CP 13)

‘The intensive workload, be it intensive in the sense of the frequency of what needs to be done. Patient care, writing physician’s letters’.(SP 36)

‘Enormous time pressure, among other things’.(CP 6)

‘The time. So due to the drastic staff reductions’.(SN 18)

‘Staff shortage which leads to some coordination problems, because not all task fields can be operated at the same time’.(CP 5)

‘It was so stressful, the chief of staff, the attending physician, they both talk, one from the left, one from the right, you have to say: ‘Hold on, I can only do one thing at once’.(SN 21)

‘To do a quick team meeting, but at that time the other work is not yet done. For example, five or three of them are in the operating room and one is still running somewhere to do something. Under these circumstances you cannot manage to start the meeting at the scheduled time when you have acknowledged that’.(CP 5)

‘At the moment we are accustomed to weekly changes with the children. So in the past we took care of a patient from admission to the end, if possible with the same nurses, which was quite good for the parents, they had fixed contact persons, but that was not so favorable for the staff, so we said we would rotate more, so that we don’t build up such a strong bond. An example, we do not always succeed in that.’.(SN 17)

‘This means that the patient arrives, registers directly with the ward secretary and the ward secretary works and then continues to give the instructions, the patient has come. So, this is already well received. Just like with the nursing auxiliary, who then does this ward help. If you know that someone got you covered, I don’t have to wipe all the tables and such, because someone will come and do it. This is definitely a relief, I can now invest five more minutes for the patient’.(SN 23)

3.2.2. Working Hours

‘Overtime hours are necessary to compensate for the follow-up service. This means that the employee usually stays one or two hours longer. I already have 88 overtimes hours this year, the other employees have about 60 to 70.’.(SN 20)

‘So, I have to, let’s say the month has 30 days on average, so with this number of employees I have to do at least six services or seven services. And this really consumes the employees over the years, so to speak.’(CP 6)

‘Because the shift and night services are also exhausting. We always have people around, mothers with children who cannot cope with shift work’.(CP 9)

‘We try to implement certain aspects like 11 o’clock coffee, that you really take a short break in between and then collect yourself before you continue, so we try to keep these things going.’(SN 18)

3.2.3. Communication/Cooperation

‘This group is so unorganized, so disorganized. This one is so big that one hand doesn’t know what the other is doing. You regularly become desperate here’.(CP 3)

‘We notice again and again that patients are badly prepared, that one does not keep to agreements.” …” If a patient is to be called up and he should be able to walk, but he is lying in bed, then the question arises: how is that possible?” … “If someone makes an order and the order is not obeyed, then you just have to ask yourself what is going on’.(CP 1)

‘We have already foreseen this situation. And we have been exchanging personnel over and over again in recent years, precisely so that we can support each other’.(SN 22)

‘if you do this together with the physicians, because they are often, I think, not even aware of what consequences are caused by a tiny little action of them, if they are simply half an hour late for a joint visit, for example’.(SN 18)

‘So, we have a pretty good relationship with our doctors, we also get along with them relatively well. We work hand in hand a lot. We don’t have to chase after them. They’re almost always there’.(SN 18)

‘If the bed manager is not there, there is no substitute and then everyone has to try to get along somehow. It’s relatively simple’.(CP 15)

‘Where physician and patient sometimes are in difficult situations even an ethics committee, which can also sometimes help us in exceptional situations’.(CP 9)

‘…we have no rotation plan, no fixed one, so we have also lost two employees to exactly such departments’.(SP 35)

‘…tries to reach the nursing service, she does not reach anyone, writes an e-mail, no reply. Maybe after three hours you’ll get an answer, see how you get along’.(CP 15)

3.3. Managers’ Perspective on the Influence of Social Factors on the Employees

3.3.1. Managers

‘In my position, 12 h a day is largely due to the fact that in the evening, when everyone is away, everyone knows the boss is there and I can just go in and talk to him. And that’s just the way it is. That’s important. Important for each individual. For me, of course, it adds up with many employees’.(CP 7)

‘I also have annual employee appraisals and when I notice that the mood is changing somewhere, I get all the people together at one table and try to moderate things’.(SN 17)

‘That it’s just totally motivating when you give people the confidence to do something and say, now you decide, it’s okay, I’m behind you, but you do it. And that’s right. And that you might be able to break through people’s reserve with something like that, people who might be a bit more cautious. And then also always with that, always with the background that they know it’s all supported by the attending, by the chief resident’.(SP 38)

‘We work hard on the processes to improve them, to create a stable team, to train employees further’.(CP 10)

‘Another point is, it is also very important to send people home, for example, when there is not much to do. Some don’t dare to do that here. They all have enough overtime. And sometimes the three of them sit in the ward at three o’clock in the afternoon, there’s nothing more to do, and I have to say that I directly address them and say which of you will go home now, because it doesn’t make sense. And I also think that it is important that people who are staying longer should be allowed to do so, it is actually only fair’.(SP 38)

‘From my point of view as a ward manager, try to make good duty scheduling’.(SN 25)

‘So, if the personnel key allows and then we sometimes deduct them from the very intensive’.(SN 17)

‘So that I often say, I’ll do it, I’ll do it, I’ll do it, so that this person when I realize he’s on the edge’.(SP 38)

‘Because then I just said, ‘Enough is enough. With this staffing, I can no longer provide the patients with the care that is necessary for them. And at that point, people really reacted to it’.(ID 27)

‘When I notice that the person concerned is not doing so well physically, they will of course talk to him. So, it is then always appealed to the instinct of self-preservation. So, sometimes, you must really show them, make them think, think a little bit more about yourself, if you were to call in sick right now, we could get help. But if you come, we won’t get any help. And whoever is here has to perform at 100, 110, 120 percent. Coming to work sick is more harmful for the team than not coming at all.’.(SN 26)

‘And only recently the managing director has repeatedly managed to find a few words that simply yes, give a little bit of support. That is not much, but nevertheless, it shows that your effort is noticed, in fact’.(SN 22)

‘I think we can more or less agree on the fact that health, the staff’s health, does not have such a high priority. Because if you thought about it, you wouldn’t call people to work on their days off, you wouldn’t let them work 200 h overtime, because at some point you have to realize that in the long run that’s not healthy for some people.” … ‘Somehow there is a lack of sensitivity when it comes to determining who is able to work under how what kind of pressure’.(SN 18)

‘Yes, proper handling is very important. I also experience this time and again in a stressful situation, for example, that I am very demanding. That I also do not tolerate delays because I am fighting for a human life’.(SP 37)

‘Yes, and otherwise I must honestly say that we have actually been waiting for some sort of praise by the management or nursing service management for years. This hasn’t happened in years. So those simple words, you did a great job, yes, something like that, yes, or something, it has never happened’.(SN 22)

3.3.2. Colleagues

‘We have despite all these issues we have a good atmosphere’.(CP 15)

‘I think we have all together always tried very hard to form a group that excludes no one. Each according to his abilities, some people are better at this, others at that, but there is no scapegoat’.(SP 34)

‘The people, people are not really used to criticism either. The fact that there are always higher demands, you have to discuss many things that could be improved and people often take this too personally immediately, which is then of course not helpful for the whole team spirit and the team’s strength, I say this now.’.(SN 17)

‘Because you can really tell that they are at the end of their rope, to put it in plain English. And yet they somehow manage to trudge through here. Some of them, where other colleagues would call in sick for minor issues, really crutch their heads under their arms to work here, because the team as such is actually already strengthened. And nobody wants to bail on the other in that moment. So, there is definitely some kind of attitude or motivation of not wanting to let the others down behind it.’.(SN 26)

‘Overload is often also seen as a weakness and therefore not mentioned by the employees’.(CP 13)

‘This high workload cannot lead to a good team building. And I believe that this team structure is also an important criterion in medicine, because you always act as a department.’(SP 35)

‘Management by waiting, for example. I just sit it out. Somebody else will takes care of it.’(SN 19)

3.4. Managers’ Perspective on the Influence of the Work Environment on the Employees

‘There are not enough computers here for all doctors and not enough rooms for everyone.’(SP 38)

‘It is just when we are sitting there with three people during the rounds, plus the two doctors, then this room is simply too small for so many voices.’(SN 21)

‘For example, we also lack premises where patients can wait sensibly. This means that some of them are really piling up in the corridor’.(SN 26)

‘The working conditions here in the unit are very acceptable for us, because we have the complete technical equipment here to immediately recognize acute deterioration or serious clinical pictures or to recognize and treat them relatively quickly. This means we are provided with the necessary equipment here in order to create good working conditions.’(SP 37)

‘So, what is motivating is that we now have a whole range of new devices that allow us to expand our therapeutic and diagnostic spectrum and which also improve workflows.’(CP 15)

‘These constant admissions, discharges, recordings. The physical is the one thing we have in basic care, the mobilization and this pressure, to get the patient healthy as quickly as possible so that he can be discharged.’(SN 24)

3.5. Managers’ Perspective on the Influence of New Working Conditions on the Employees

3.6. Other Factors Influencing the Employees’ Mental Health

‘There are competent doctors who are not able to handle certain situations well due to their character or it is just not so easy for them, others handle it very well, or at least seem to do so.’(CP 13)

‘Highly professionalized, well-structured sector working according to algorithms, guidelines and evidence. This means that there is no possibility of involving your psyche in between.’(SP 37)

‘Nobody talks about how bad a day was, nobody says they will probably not make it tomorrow. People also try not to admit to themselves that they are burdened emotionally. And I think that’s something that naturally leads to people always carrying their emotional tension with them.’(SP 37)

‘So, there are also various athletic activities here. But also, and this plays a very important role for me, these are medically inactive stories’(SP 31)

‘Yes, all the way to oncology, where one, which is really also care-intensive and one experiences how, my impression in this area is that they have a very good strategy for dealing with the stress.’(SP 36)

‘Overload indicators can be made. But there it is about the burden of too much work, if you are only two people instead of three on a nursing ward or something, or if you are alone and have severe cases, you can’t cope with, then you can do that.’(SN 21)

‘Yes, and if we can no longer help ourselves alone, we turn to nursing service. And, of course, hiring temporary staff is the last resort.’(SN 22)

4. Discussion

4.1. Staff Shortage as a Core Problem

4.2. Results in the Light of Relevant Stress Models

4.3. Results in the Light of the Factor Social Support and The Psychosocial Safety Climate

4.4. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Characteristics Area | Sub-Categories | Possible Critical Expression |

|---|---|---|

| Work Task | Emotional demands | by experiencing emotionally very touching events (e.g., dealing with serious illness, accidents, death) by constantly responding to the needs of other people (e.g., customers, patients, students) through permanent showing of demanded emotions independent of own sensations threat of violence from other people (e.g., customers, patients) |

| Responsibilities | unclear competences and responsibilities | |

| Decision latitude | The employee(s) has/have no influence on work content workload working methods/-procedures sequence of activities | |

| Qualification | activities do not correspond to the qualification of employees (over/underchallenge) insufficient briefing/introduction to the job | |

| Information Offer | too extensive (stimulus satiation) too low (long periods without new information) unfavorably presented information Inadequate (important information missing) | |

| Variability/Diversity of tasks | one-sided requirements: few, similar work objects and work equipment frequent repetition of similar actions in short cycles | |

| Completeness of the task | Working activity involves: - only preparatory or - only executive or - controlling actions only | |

| Work Organization | Working hours | changing or long working hours unfavorable shift work, frequent night work extensive overtime inadequate break regime work on call |

| Work process | time pressure/high work intensity frequent faults/interruptions high clock rate | |

| Communication/Cooperation | isolated single workstation no or little possibility of support by superiors or colleagues no clearly defined areas of responsibility | |

| Social Factors | Colleagues | too low/too high number of social contacts frequent disputes and conflicts Nature of conflicts: social pressure situations lack of social support |

| Managers | no qualification of the managers lack of feedback, lack of appreciation lack of leadership, lack of support in case of need | |

| Work Environment/Equipment | Design of the Workplace and of Information Stimuli | unfavorable working areas, spatial narrowness inadequate design of signals and notices |

| Work Equipment | missing or unsuitable tool or work equipment unfavorable operation or setup of machines insufficient software design | |

| Physical and Chemical Factors | Noise Lighting Hazardous substances | |

| Ergonomic Factors | unfavorable ergonomic design hard physical work | |

| New Working Conditions | These characteristics are not the subject of supervisory action but play a role in the stress situation of employees. | spatial or temporal flexibility reduced delimitation between work and privacy |

| Main Categories | Sub-Categories | Chief Physicians | Senior Physicians | Senior Nurses | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work Task | Emotional Demands | 11 | 6 | 12 | 29 |

| Responsibility | 10 | 3 | 1 | 14 | |

| Decision Latitude | 5 | - | 4 | 9 | |

| Qualification | 2 | 1 | 4 | 7 | |

| Information Offer | 4 | - | - | 4 | |

| Variability/Diversity of tasks | - | - | 4 | 4 | |

| Completeness of the Task | - | - | 1 | 1 | |

| Total Work Task | 32 | 10 | 26 | 68 | |

| Work Organization | Work Process | 30 | 21 | 42 | 93 |

| Working Hours | 15 | 11 | 16 | 42 | |

| Communication/Cooperation | 14 | 7 | 12 | 33 | |

| Total Work Organization | 59 | 39 | 70 | 168 | |

| Social Factors | Colleagues | 6 | 3 | 6 | 15 |

| Managers | 4 | 7 | 4 | 15 | |

| Total Social Factors | 10 | 10 | 10 | 30 | |

| Work Environment | Workplace | 3 | 1 | 4 | 8 |

| Work Equipment | - | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Ergonomic factors | - | - | 1 | 1 | |

| Physical and chemical Factors | - | - | - | - | |

| Total Work Environment | 3 | 2 | 7 | 12 | |

| New Working Conditions | - | - | - | - | - |

| Other Stressors | - | 2 | 5 | 1 | 8 |

| Total | 286 |

| Main Categories | Sub-Categories | Chief Physicians | Senior Physicians | Senior Nurses | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work Task | Emotional Demands | 1 | 2 | 4 | 7 |

| Responsibility | - | - | - | - | |

| Decision Latitude | 4 | 2 | 4 | 10 | |

| Qualification | 3 | 1 | - | 4 | |

| Information Offer | 2 | - | 1 | 3 | |

| Variability/Diversity of tasks | - | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Completeness of the Task | - | - | - | - | |

| Total Work Task | 10 | 6 | 10 | 26 | |

| Work Organization | Work process | - | - | 4 | 4 |

| Working hours | - | - | 1 | 1 | |

| Communication/Cooperation | 3 | 2 | 6 | 11 | |

| Total Work Organization | 3 | 2 | 11 | 16 | |

| Social Factors | Colleagues | 6 | 4 | 13 | 23 |

| Managers | 32 | 7 | 31 | 70 | |

| Total Social Factors | 38 | 11 | 44 | 93 | |

| Work Environment | Workplace | - | - | - | - |

| Work Equipment | 1 | 1 | - | 2 | |

| Ergonomic Factors | - | - | - | - | |

| Physical and Chemical Factors | - | - | - | - | |

| Total work environment | 1 | 1 | - | 2 | |

| New Working Conditions | - | - | - | - | |

| Other Resources | - | 2 | 3 | 5 | |

| Total | 142 |

Appendix B

| Emotional Demands |

| WT-E1: The delivery of bad news. For example, a prognosis or even brain death, or in case of serious diseases that lead to death over a very long period of time. (SP 36) |

| WT-E2: I work in a specialty where the clinical pictures are already very difficult, and the problem is that we have patients, that is not Mr. Müller, Mr. Meier, Mr. Schmidt, it IS Mr. Müller, we know him, we have accompanied him for years. And we usually care for them until they die, and then it’s not just a patient who has died, but Mr. Müller who has died. (SN 16) |

| WT-E3: Staff have to respond immediately to changing events. There’s always a certain basic tension in the process, you can’t get rid of. (SP 37) |

| WT-E4: The surgical successes that we have, that after an operation, the patients are not only satisfied with the operation itself but also with the way we treat them and that to a large extent. (SP 32) |

| WT-E5: here lies no one with a cold, confronted with the need to preserve life. That usually works out pretty well. We have a high success rate. (SP 37) |

| WT-E6: Especially with the seriously ill patients, or even less ill patients, it is already a good feeling when you can help. (CP 13) |

| WT-E7: So, you actually see motivation with the trauma surgeons, for example, they usually come after accidents or so, when they can walk again or the gait training begins in general and they are then perhaps transferred to geriatrics for rehabilitation, that is of course already a motivation, I always think when patients get to walk again. (SN 23) |

| WT-E8: There are motivating experiences indeed. So of course, I was just talking about the babies, when they have grown nicely, when they are doing well, when the parents go home happily, this is transferred to the employees, who are also happy. Or when we had very seriously ill children, who then go home after a certain time, we are also happy. (SN 25) |

| WT-E9: Great patients, you like to work with, where you can see successes who go home well. That is simply beautiful. Really still nice. Fascinating, exciting, new. (SN 29) |

| Responsibility |

| WT-R1: Especially in dealing with patients with whom communication is difficult. In other words, we have many patients here in this hospital, of course, which is simply due to the situation, with a migrant background, who often cannot speak our language. And it is a burden for the staff to be able to adequately communicate with the patients. (SP 32) |

| WT-R2: In addition, of course, the medical responsibility itself during complex procedures. (SP 31) |

| WT-R3: Situations where we partly find ourselves in an ethical dilemma when it comes to medical decisions. (CP 9) |

| Decision latitude |

| WT-DL1: A burden that we have because of the so-called administrative activities. And that which is nerve-racking in everyday now speaking of me personally, this is something we have observed with colleagues. Because when things get stuck, so to speak, you get the feeling that you can no longer really take care of the actual job you have learned. (CP11) |

| WT-DL2: Then you have to figure out what to leave out. First and foremost, according to priorities, the documentation that is not necessary or that at least for the moment does not seem necessary. The supply of medication is important. (SN 20) |

| WT-DL3: The opportunity to design areas responsibly and to have the resources to do so. To recognize and define for yourself what is important for patients, to be there for them, in an adequate way. And what you need for that. And then also in fact have the opportunity to be able to shape this. (CP 7) |

| WT-DL4: That I also give him the opportunity to deepen his own experiences in special examination techniques. And he also has the opportunity to develop and shape this area. … ‘that you have the opportunity to organize yourself and shape your working environment (SP 36) |

| WT-DL5: That it’s just totally motivating when you give people the confidence to do something and say, now you decide, it’s okay, I’m behind you, but you do it. And that’s alright. (SP 38) |

| WT-DL6: They work relatively independently, they know all the activities, they can actually do what I do, from the evaluation and so on. Some employees work independently and say I’m going to finish this and tell me that. (SN 21) |

| WT-DL7: So as long as the shop is running and we stick to hygienic guidelines, we are allowed to do and act as we want. (SN 27) |

| WT-DL8: It is often the case that we then agree on doing certain operations more often or being allowed to learn more or developing further or supervising doctoral students, answering scientific questions, something like that. (CP 12) |

| WT-DL9: Hey, have you ever thought of having people write their own rosters?’ I’ll just try that out. Of course, it’s always difficult with three shifts, but I try to make it possible, things like that, so that you say: ‘Okay, we can try it. If everyone notes down which shifts are most suitable for them, we’ll just see how it works, if that works.’ I definitely try to avoid such service obligations. And I always try to find out if something can be done or made fit differently, so that nobody needs to come additionally. (SN 18) |

| Qualification |

| WT-Q1: As I see it, jobs in the care sector are relatively ungrateful because there are too few opportunities for advancement and development, and that is a problem. (SP 36) |

| WT-Q2: But the satisfaction, I would say, I see at least also with my employees, if they can successfully complete tasks, depending on their level of performance, of course they can and want to be entrusted with new tasks. … I also believe that it is definitely pleasant for employees, even for a younger assistant physician in further training, when they made the right decision there, when he came to the right diagnosis in emergency service. (CP 9) |

| WT-Q3: I think I also really strengthen them when it comes to conveying specialist knowledge, and then supporting them, demanding and encouraging their way of thinking in an evidence-based way. (CP 3) |

| WT-Q4: that I also give the opportunity to deepen his experiences in special examination techniques.” … “then I think it’s essentially the case with assistants that you teach them something in terms of training, that they learn something new. In return, I also expect that patients are properly cared for, that the documentation is correct, that the physician’s letters are correct. And then on our part, the opportunity to learn physical neurological examination and perhaps also to learn one or the other part, or an intervention, which is relevant for the internists. (SP 36) |

| Information offer |

| WT-IO1: So, we also have handovers in the morning, which used to be exclusively medical. Now everyone is invited. So, care, therapists, social workers. So that we all meet at half past eight in the morning for about half an hour and then we also discuss what was going on in the services, what is to be discussed organizationally, which transfer is scheduled. (SN 29) |

| Variability/Diversity of tasks |

| WT-V1: So, if the personnel key allows and then we do the following, they are then deducted from the very intensive and then first make a week of rearing the children or something like that to come down again then. (SN 17) |

| Work Process |

| WO-WP1: The situation is different if only one person out of the three positions is appointed, or two people are appointed. Then it does not work that way. Then this person has to work or think at two positions at the same time or handle the tasks one after another. (CP 5) |

| WO-WP2: At the moment when several patients are causing problems, it’s like you’ve read before, that you are actually just running past it and noticing: ‘Oh, he has just pulled his artery, I should actually go in there, but I can’t, because you have to go back there. And I think that is the most stressful thing for people, that you can’t work with foresight anymore, but you’re really just working, you’re just reacting to what’s happening right now. (SN 18) |

| WO-WP3: We’ve got a lot of work, it’s really stressful. Of course, it is also difficult for some people because of the work density. (CP 15) |

| WO-WP4: In the past, there were handover books where you wrote a sentence to a patient, finished. Things are much different today. It is yes, everything has increased. And the staff has decreased. And everything else has increased. (SN 25) |

| WO-WP5: In the field of anesthesia, the time pressure in the operating room is certainly a stress factor for employees. (SP 31) |

| WO-WP6: …Another problem is, this inconsistency of work, because services exist, so this is a problem that has also arisen with the Working Time Act, that I now have more shift systems and colleagues go to services or other functions and therefore constant patient care is no longer possible. In other words, they look after a patient for a day and then go somewhere else again. And then they eventually see him again. This causes a lot of dissatisfaction in my work and also in the work of my colleagues. (SP 36) |

| WO-WP7: Appointment compression simply by short retention periods, relatively high turnover, you have to adapt to new patients relatively quickly again and again. Has relatively little time for the individual patient. Simply the high flow of patients. (SP 40) |

| WO-WP8: …that the pressure is not even. We have days when the ward can be full to the brim and I can comfortably sit in the kitchen with three others and drink coffee and then I have days when I only have four patients and I don’t know how I am going to look after these patients with three colleagues. There are really high load peaks, this can happen all of a sudden. There is no pattern or regularity. I cannot assume that this will always be the case in winter or in summer or on Thursday or on Friday, or whatever. There is no regularity. It can happen any second, relatively quick. (SN 18) |

| WO-WP9: It’s mentally exhausting when the phone is ringing all day long, I remember that from my old employer, there I also sometimes sat with the secretary next door and she also did the bed planning and then the phone went from morning to evening and then still in the evening, she was worn-out from all these phone calls, all this writing down, the things she had to keep in mind, you must not forget anything, you have to keep track of everything, she was harassed by the phoning and by writing down, by noticing, you mustn’t forget anything, you have to keep track of everything. (CP 12) |

| WO-WP10: In many areas there is no clear definition of the employee’s task. Due to frequent rotations, people are confused and do not know. And then they are sometimes, this is extremely frustrating when you don’t know what I have to do, what I am responsible for, what you are not responsible for. (CP 13) |

| WO-WP11: But what I also partly deal with is the current discharge management, where doctors can’t get involved, for whatever reason, patients are often discharged as late as in the afternoon because the letters are not ready yet. (SN 20) |

| WO-WP12: …but we have no rotation plan, no fixed one, so we have also lost two employees exactly to such departments. (SP 35) |

| WO-WP13: Now that we have new legislation, that we have to have a higher personnel key on level one in the intensive care unit in order to guarantee one-to-one care, that helps us to the extent that when we have reached this personnel cut at some point, we simply have more time for the whole thing and not always have to chase work, which is often the case. (SN 17) |

| WO-WP14: Delivery at the bedside.… Our colleagues have seen many advantages of that. As I said, the fact that this first round of the late shift, which is already superfluous, because there are two colleagues, the early shift and the late shift, who take care of the patient together, this means that certain things that the early shift might not have noticed are immediately recognized by the late shift. (SN 24) |

| Working Hours |

| WO-WH1: When a patient has died, he is prepared, brought down and the work continues immediately. There is not even a moment where you can take some time to reflect and say, well, okay, that’s done now, and I want to go and have a sip of coffee and then continue. Sometimes that’s missing. (SN 23) |

| WO-WH2: …that is, length of service, rotating shifts every weekend. In my opinion, there are not enough buffers. (SN 19) |

| Communication/Cooperation |

| WO-C1: or even the pick-up and delivery service simply does not come and does not pick up the patients and so on. (SN 18) |

| WO-C2: So, the choir spirit, is not as you might want it to be. This is due to the great organizational complexities of this house. There is not one large group, but many small ones, which often change among themselves. (CP 13) |

| WO-C3: In my everyday life I experience that there is far too little direct communication with each other, instead a lot of communication takes place in writing via entries and consults, because you do not spend enough time together with the patient. So, I think that we do not spend enough time together in joint visits. Nursing, assistant physician rarely visit together, where problems could be discussed directly together. (SP 36) |

| WO-C4: When things get stuck, so to speak, you have the feeling that you can’t really take care of your actual job, could you have learned, because you are too busy, making appointments, asking questions, organizing things that could actually be delegated, but often, these things cannot properly be implemented so you end up doing all of it yourself. CP 11) |

| WO-C5: Do not want to say that it is not, but then to call, I am not feeling well today, I will not come to work today. And yes, I’m on duty tomorrow, but I’ll come to duty then and do the whole thing. So, there is so much awareness, sense of responsibility, because otherwise they know very well that there is a gap, someone else has to fill. (CP 6) |

| WO-C6: Specifically, that of course we have additional staff available, who then take over such overlapping functions that we always have specialists available, SP available, who help people in such critical medical situations and provide assistance. (SP 31) |

| WO-C7: We have a lethality conference which takes place once a week, where such topics are also discussed. (SP 32) |

| WO-C8: For example, a colleague of the chief physician told me that she had had a particularly stressful situation in the intensive care unit with relatives. And what kind of supportive offer we have in our department for her employees as support, where we could come and talk, a supportive offer for her employees as support. Yes. We do that on the spur of the moment. Short-term, informal interventions, as needed, yes. (CP 4) |

| WO-C9: Which is fine, I don’t know if you mean that, we have a psychooncologist in the house. That is quite good, because whenever I really notice that there is a need for a conversation or there is a physician with a new disease pattern or a new condition and unfortunately we cannot take the time to sit down and talk to him, then we switch her on and she has the time, takes the time and then we have the feeling that we have done something for the patient anyway. (SN 16) |

| WO-C10: we also have a nursing case meeting. There we can also address certain issues or problems, but this is for the whole house. (SN 16) |

| WO-C11: but we do have supervision on our side. So, and this is also clarified within the framework of supervision. (SN 29) |

| Colleagues |

| SF-C1: So, there’s this tension like, where do I see myself on the team, how do I deal with my colleagues. How do I fit in with the team. (CP 9)SF-C2: So, the choir spirit, it is not as you might want it to be. (CP 13) |

| SF-C3: The team as such just wants to get out even more, more, more. And thereby compensating for structural weaknesses to the point of self-sacrifice. (CP 7) |

| SF-C4: Physical aches and pains come with increasing age, or rather no longer aches and pains, but real problems and the whole team suffers from them. So those who are sick and those who are still there have to cope with it and then they also get sick at some point. I wish I had a mixture of young and old. (SN 16) |

| SF-C5: And I have a good team with a good atmosphere, we also exchange ideas with each other. So that works out well. (SN 25) |

| SF-C6: The interdisciplinary cohesion, but also in our department the very close cooperation, where contact and conversation is possible at any time. (SP 32) |

| SF-C7: We work extremely well together as a team, that has to be said. That’s also, you get along with the people, that’s also real, there are no people, almost without exception, that you would not consider as part of the team here. (CP 2) |

| SF-C8: To have a team together that thinks and feels similarly so to say. And that knows each other so well that you know the personal strengths and weaknesses in the team and of course you can compensate for them. (CP 7) |

| SF-C9: Most of the employees I know are motivated in their job and I think that is very, very important for the team spirit. (CP 5) |

| SF-C10: Team spirit is pretty good I’d say. (SN 17) |

| SF-C11: that we’re also having dinner with the team. That we not only meet at work and talk about patients and stuff. But they go out, and we go out to dinner. (SN 16) |

| SF-C12: So, on the one hand, I think we motivate each other ourselves. That we not only meet at work, but also privately from time to time. And then we have a barbecue or whatever. (SN 22) |

| SF-C13: what is quite important for us is that we have a relatively good team, we have grown together really well, they have known each other for a long time and they like to work together, some of them also spend time together apart from work. I think that makes a big difference. (SN 18) |

| SF-C14: I say, for private time, that we do this together. For example, we were planning a trip. (SN 28) |

| SF-C15: That’s why it’s also important that we do a lot of let’s call it mental hygiene with our team, also colleagues among each other, I’d say. (SN 16) |

| SF-C16: So, we often talk about what patients trigger and cause in us. We always call this our little group. This is certainly connected to the field of expertise, our colleague is still a psychiatrist, so in this respect we are more familiar with perceiving what patients trigger in us, what situations also trigger in us. And occasionally reflect on this together during the lunch break. (SP 36) |

| SF-C17: We also laugh a lot, we also fool around, and we sometimes talk about private things, that is also completely legitimate.” … “the one who would intercept this emotional crisis of the other. Usually it is the best colleague or the one who is currently on duty with whom you get along well. That you talk about it. (SP 37) |

| SF-C18: Otherwise we have regular station meetings and if such a case gets out of character, supervision. (SN 17) |

| SF-C19: The cooperation among the employees, the feeling that they support each other. (CP 4) |

| SF-C20: So, we are definitely trying to help each other. (SN 24) |

| SF-C21: Sometimes it also happens that the group itself then says “okay, can I take something off your hands?” and that would certainly be another point to strengthen that. (CP 13) |

| Managers |

| SF-M1: Employees also do not get the feeling that they receive the support they need, because he knows exactly that six positions are missing. (CP 6) |

| SF-M2: It was planned and agreed by me that she would then remain as a specialist, in her three-quarters position, so that it would be compatible with family life, for an unlimited period, so that she could, she had this promise. When this examination came, I also passed this on to her, suddenly, different than what had been agreed upon beforehand, the statement that she could only be employed for a limited period of time. This might seem like a small issue from afar, but for such a person it is dramatic. Dramatic for her, dramatic for me too, because it contradicts my promise. (CP 7) |

| SF-M3: That they know they have a boss who stands up for them. I think I’m doing pretty well. At least, that’s what I hope anyway. At least that’s the feedback I get. It’s very important to me. So, the duty of care for the employees. (CP 15) |

| SF-M4: A certain closeness means addressability for me. My employees know that they can actually address me at any time. (CP 5) |

| SF-M5: Or the comforter when a colleague’s brother has recently been diagnosed with cancer. That ranges from business situations, where supervision is required, to very pragmatic situations, in the sense of an open ear in family stories. (CP 4) |

| SF-M6: If someone here has any topic family, partner, work, employee, colleague, that the door is open at any time, that they can relieve themselves here. And every time someone says he has to go to physiotherapy at 3 pm, I would never stop him. So that’s when they get—and I’ve said this quite often—my full support immediately. (CP 3) |

| SF-M7: Seeking direct conversation. Try to... yes, like I said, try to have a direct conversation first, to find out if this is right... sometimes I hear about it from others. And there you can only accompany or give support. (CP 1) |

| SF-M8: Is important, I think, because an open communication structure, so yes, you hear it again and again in the management seminars, the open door of the boss, but that is also lived here. (CP 2) |

| SF-M9: I am also very close to the staff. We really support them a lot, they can come to us with any questions. (CP 10) |

| SF-M10: But I would say that I have an open mind to look at that as well. And where you then notice that employees are perhaps, let’s say, harder on themselves, you can also follow up. That would now be the second thing, the intervention. So that you basically not only perceive that, but basically also look, okay, can I then relieve someone, simply take them out of a situation. (CP 11) |

| SF-M11: Through team meetings and regular get-togethers, eating together, for example, we already try to create an atmosphere in which you can get rid of non-work related issues or by having a certain proximity to the employees, “…”So we have relatively flat hierarchies, I also listen to it when I notice that one—this does not only concern the physicians it also concerns nursing and the other therapists, who are located somewhere between the nursing and the doctors in their work and who are also very stressed. If I notice this, I invite them to a conversation as well. (CP 13) |

| SF-M12: Of course, we also try to discuss such things when they are dramatic things that also happen here in everyday work. (CP 9) |

| SF-M13: So, they also come to me, even if it has nothing to do with the profession as such, and they also come to me with very private questions, problems and worries. (SP 33) |

| SF-M14: we try to arrange it that way when the employees come, I always say: ‘come anytime, whenever there is something wrong.’ (SN 17) |

| SF-M15: We brought it up there and tried to talk about it. What could be done differently, that you don’t get the feeling, what have I done wrong. There are definitely a few possibilities. (SN 16) |

| SF-M16: To have conversations and try to really reach people. (SN 26) |

| SF-M17: When I see that someone is suffering, conversation is the way to go, a very brief five-minute conversation, or “Is there anything I can do here? Is something wrong? You just ducked out?” Sometimes it’s also private things that are included in the job. For example, when your father has passed away. And the employee is then completely shocked on duty and I don’t know what to do in the first place. You have to see if you can get someone from somewhere else and say, “Go home.” Overtime cutbacks, or even the legal cutbacks that you have when a parent dies. That’s important. (SN 20) |

| SF-M18: in my ward, I definitely pay attention when I see that someone is depressed, or maybe I in a way notice that they are somehow different or something, I talk to them about it and always ask them if something happened, if something is going on. (SN 23) |

| SF-M19: I can read faces. If I see that you are not well, I can easily recognize that, then I take him aside and ask him what worries and troubles him, but never in front of the others, rather in a four-eye conversation. (SN 25) |

| SF-M20: So, we do team meetings. (SN 28) |

| SF-M21: So, I don’t know how often I sit here with staff and really take them aside, even after work, just talk to each other for ten minutes after the handover, just to listen, check the situation, how are you doing right now. What can I do for you, because I notice that you are under pressure? What do you need right now to feel a little bit relieved? I’m trying to do whatever is possible for me. But especially as their superior, there are also some things I cannot do. (SN 27) |

| SF-M22: You just have to be careful not to disturb, trying to defensively prevent escalation and you can only do this to a certain extent if you are not like: That is your fault, you have to go through this now, but if you say: “look, I still have three or four emergencies and I can still help you” or “leave it alone, you’d better do it”. Provide clear structures to make employees feel a sense of relief. (SN 20) |

| SF-M23: Communication with each other. This is something I tried to convey relatively early, that you have to treat everyone friendly and respectfully. (CP 1) |

| SF-M24: Something I really like is highlighting the things that have been going well in the last weeks and months. Which of course is also a bit motivating for the team. (SN 26) |

| SF-M25: But I think we have found this way here, which should actually make it relatively easy for the people to feel comfortable, I think. (CP 12) |

| SF-M26: Try to create a certain atmosphere. (CP 13) |

| SF-M27: Well, I’ve been in charge of the ward for two years now and I’ve introduced the idea that we also have dinner with the team. (SN 16) |

| SF-M28: So, I have to say, I am a calm person that means it doesn’t matter how much stress there is or how much we are burning I try, I am in rage, but I try to stay calm. Because when I am excited, then my employees do the same and then everything goes wrong so you have to stay calm and get an overview, and I hope I succeed in that. (SN 16) |

| SF-M29: I also know that it’s good for me to stay calm and then say, “Do this, do that, do that.” I’ve also heard that from colleagues, they say, “How can you stay so calm under all this stress?” “Yes,” I say, “On the outside, I’m calm. It doesn’t help when I’m nervous here. (SN 21) |

| SF-M30: Go home early, send... if possible. (CP 2) |

| SF-M31: The other is perhaps measures where you try to create temporary help in the workloads, so that you can create more space for recreational value, in an open space, so to speak. (CP 11) |

| SF-M32: But there is significantly more overtime in winter than in summer. But there is a good cooperation with the nursing management, which accepts this and says that overtime will be reduced in summer. (SN 25) |

| SF-M33: If you say I somehow need a week’s vacation, that I’ll say, look, how about taking a week’s vacation and then immediately afterwards a week off overtime, then I’ll try to cycle the vacation planning so that the employee doesn’t have to sit on like 300 overtime hours, but can also reduce them promptly. And that does not mean reducing them according to what is best for me or for the company, but also when it suits the employee, as well. (SP 35) |

| SF-M34: I think everyone I talk to about this, we always talk once a year, a further training talk and personal development talks. (CP 12) |

| SF-M35: We talk about personnel development with our employees at least once a year. This concerns the level of professional training, but also the level of personal development. (CP 9) |

| SF-M36: And we do these talks, these personnel development talks. They sometimes tell you what bothers them. (SN 28) |

| SF-M37: We conduct regular employee appraisals. (CP 10) |

| SF-M38: Employee appraisals, we do those too, of course. (CP 15) |

| SF-M39: Yes, you try, let me put it this way, to accommodate the employee by saying, okay, fine, you arrange certain leisure activities that fit into your system. (CP 6) |

| SF-M40: So, we have a very transparent vacation schedule, a very transparent duty roster, so that you can also see who has done how much work and who does what when, so that there are no great inequalities, so that it’s not the case that some people work the whole weekend, several weekends in a row, and others not at all. On the contrary, there is a way of ensuring that there are equal rights. (CP 2) |

| SF-M41: In the rostering, that you give everyone a goodie and then people jump in when you want them to. So that’s where I think it’s very important to keep everyone equal. (SN 17) |

| SF-M42: So, I try to equally distribute it, not always the same people, so to say, I say, when it is about coming for a weekend more, I do my best. (SN 18) |

| SF-M43: I try to fulfill the wishes of the employees as good as possible. For example, the employees can already participate in the duty planning and simply enter the yes, the desired services where they need free time or vacation anyway of course. And we try to respect that. (SN 22) |

| SF-M44: That one also looks at the distribution, that it is also fair. (SN 17) |

| SF-M45: I’m just trying to spread the load evenly, like I said. (SN 18) |

| SF-M46: I have an eye on the mental health of the employees, respond to their wishes regarding holiday planning, further education wishes, duty roster design, a support by taking over tasks of the employees. (SP 31) |

| SF-M47: So that’s when you try to remind people, ‘Take the break.’ Then I say, ‘Yes, I’m here, I’m doing this work. Now you go and leave. (SN 21) |

| SF-M48: When I’m on duty with a colleague and simply recognize her facial expression, certain yes, characteristics now, because she’s about to burst. Then I say, then I’ll go in between and say, I’ll take over certain things, I’ll take it from you. But okay, I can do that. (SN 24) |

| SF-M49: Sometimes there is no other way and we also try to relieve ourselves, so that not one of us is standing there all the time, especially when we have long reanimation or so that we always change, so that not only one of us is affected and we try to take the other patients away from the one who has a lot to do with his patients, so that he can just concentrate on one. (SN 18) |

| SF-M50: I try to reduce the burden by asking the nursing service management to hire more staff so that the few employees we have don’t have too much work, too much overtime, which shouldn’t happen at all. In that case I don’t know whether they do not want to do it or cannot do it, because they might have received instructions from the hospital to save on personnel or something. (SN 21) |

| SF-M51: I see it as my responsibility to look out for my employees, to check the workload. And do I perhaps have to offer them a helping hand and talk to my superior to check if the number of staff needs to be increased because the mental, psychological and physical strain is simply too high for the staff who are currently working there. (SN 23) |

References

- Angerer, P.; Petru, R.; Nowak, D.; Weigl, M. Arbeitsbedingungen und depression bei Ärzten. Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr 2008, 133, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisljar, T.; van der Lippe, T.; den Dulk, L. Health among hospital employees in Europe: A cross-national study of the impact of work stress and work control. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coutinho, H.; Queirós, C.; Henriques, A.; Norton, P.; Alves, E. Work-related determinants of psychosocial risk factors among employees in the hospital setting. Work 2018, 61, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent-Thirion, A.; Isabella, B.; Cabrita, J.; Vargas, O.; Vermeylen, G.; Wilczynska, A.; Wilkens, M. Sixth European Working Conditions Survey; Eurofound: Dublin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Parent-Thirion, A.; Hurley, J.; Vermeylen, G. Fourth European Working Conditions Survey; European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions: Dublin, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Von dem Knesebeck, O.; Klein, J.; Frie, K.G.; Blum, K.; Siegrist, J. Psychosoziale Arbeitsbelastungen bei chirurgisch tätigen Krankenhausärzten. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2010, 107, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiken, L.H.; Sermeus, W.; Van den Heede, K.; Sloane, D.M.; Busse, R.; McKee, M.; Bruyneel, L.; Rafferty, A.M.; Griffiths, P.; Moreno-Casbas, M.T.; et al. Patient safety, satisfaction, and quality of hospital care: Cross sectional surveys of nurses and patients in 12 countries in Europe and the United States. BMJ 2012, 344, e1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- LePine, J.A.; Podsakoff, N.P.; LePine, M.A. A meta-analytic test of the challenge stressor–hindrance stressor framework: An explanation for inconsistent relationships among stressors and performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Angerer, P.; Weigl, M. Physicians’ psychosocial work conditions and quality of care: A literature review. Prof. Prof. 2015, 5, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; LePine, J.A.; LePine, M.A. Differential challenge stressor-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 438–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degen, C.; Li, J.; Angerer, P. Physicians’ intention to leave direct patient care: An integrative review. Hum. Resour. Health 2015, 13, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- West, C.P.; Tan, A.D.; Habermann, T.M.; Sloan, J.A.; Shanafelt, T.D. Association of resident fatigue and distress with perceived medical errors. JAMA 2009, 302, 1294–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, S.; Shanafelt, T.D.; Sinsky, C.A.; Awad, K.M.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Fiscus, L.C.; Trockel, M.; Goh, J. Estimating the attributable cost of physician burnout in the United States. Ann. Int. Med. 2019, 170, 784–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rau, R.; Buyken, D. Der aktuelle Kenntnisstand über Erkrankungsrisiken durch psychische Arbeitsbelastungen. Z. Arb. Organ. A&O 2015, 59, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theorell, T.; Hammarström, A.; Aronsson, G.; Bendz, L.T.; Grape, T.; Hogstedt, C.; Marteinsdottir, I.; Skoog, I.; Hall, C. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and depressive symptoms. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Theorell, T.; Jood, K.; Järvholm, L.S.; Vingård, E.; Perk, J.; Östergren, P.O.; Hall, C.A. systematic review of studies in the contributions of the work environment to ischaemic heart disease development. Eur. J. Public Health 2016, 26, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- ILO. Workplace Stress: A Collective Challenge; International Labour Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gemeinsame Deutsche Arbeitsschutzstrategie (GDA). Leitlinie Beratung und Überwachung bei Psychischer Belastung am Arbeitsplatz; Geschäftsstelle der Nationalen Arbeitsschutzkonferenz c/o Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gregersen, S.; Kuhnert, S.; Zimber, A.; Nienhaus, A. Führungsverhalten und gesundheit–zum stand der forschung. Das Gesundh. 2011, 73, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, K. Review article: How can we make organizational interventions work? Employees and line managers as actively crafting interventions. Hum. Relat. 2013, 66, 1029–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourbonnais, R.; Brisson, C.; Vinet, A.; Vézina, M.; Abdous, B.; Gaudet, M. Effectiveness of a participative intervention on psychosocial work factors to prevent mental health problems in a hospital setting. Occup. Environ. Med. 2006, 63, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourbonnais, R.; Brisson, C.; Vézina, M. Long-term effects of an intervention on psychosocial work factors among healthcare professionals in a hospital setting. Occup. Environ. Med. 2011, 68, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, F.; Bunce, D. Job control mediates change in a work reorganization intervention for stress reduction. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2001, 6, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJoy, D.M.; Wilson, M.G.; Vandenberg, R.J.; McGrath-Higgins, A.L.; Griffin-Blake, S. Assessing the impact of healthy work organization intervention. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 139–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrou, P.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Crafting the change: The role of employee job crafting behaviors for successful organizational change. J. Manag. 2016, 44, 1766–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lundmark, R.; Hasson, H.; von Thiele Schwarz, U.; Hasson, D.; Tafvelin, S. Leading for change: Line managers’ influence on the outcomes of an occupational health intervention. Work Stress 2017, 31, 276–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offermann, L.R.; Hellmann, P.S. Leadership behavior and subordinate stress: A 360 degrees view. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1996, 1, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1996, 1, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R. Lower health risk with increased job control among white collar workers. J. Organ. Behav. 1990, 11, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J. Organizational injustice as an occupational health risk. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2010, 4, 205–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubicek, B.; Korunka, C.; Tement, S. Too much job control? Two studies on curvilinear relations between job control and eldercare workers’ well-being. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2014, 51, 1644–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? Field Methods 2016, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2015, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kyngas, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken, 12th ed.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, W.J.; Levine-Donnerstein, D. Rethinking validity and reliability in content analysis. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 1999, 27, 258–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Morgeson, F.P.; Johns, G. One hundred years of work design research: Looking back and looking forward. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blum, K. Fachkräftemangel und Stellenbesetzungsprobleme im Krankenhaus—Bestandsaufnahme und Handlungsoptionen. In Arbeiten im Gesundheitswesen (Psychosoziale) Arbeitsbedingungen—Gesundheit der Beschäftigten—Qualität der Patientenversorgung, 1st ed.; Angerer, P., Gündel, H., Brandenburg, S., Nienhaus, A., Letzel, S., Nowak, D., Eds.; Ecomed Medizin: Landsberg am Lech, Germany, 2019; pp. 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Statistisches Bundesamt. Grunddaten der Krankenhäuser; Statistisches Bundesamt: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll, A.; Grant, M.J.; Carroll, D.; Dalton, S.; Deaton, C.; Jones, I.; Lehwaldt, D.; McKee, G.; Munyombwe, T.; Astin, F. The effect of nurse-to-patient ratios on nurse-sensitive patient outcomes in acute specialist units: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2018, 17, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, S.B.; Modini, M.; Joyce, S.; Milligan-Saville, J.S.; Tan, L.; Mykletun, A.; Bryant, R.A.; Christensen, H.; Mitchell, P.B. Can work make you mentally ill? A systematic meta-review of work-related risk factors for common mental health problems. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 74, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.V.; Hall, E.M. Job strain, work place social support, and cardiovascular disease: A cross-sectional study of a random sample of the Swedish working population. Am. J. Public Health 1988, 78, 1336–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jalilian, H.; Shouroki, F.K.; Azmoon, H.; Rostamabadi, A.; Choobineh, A. Relationship between job stress and fatigue based on job demand-control-support model in hospital nurses. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 10, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richer, S.F.; Vallerand, R.J. Supervisors’ interactional styles and subordinates’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. J. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 135, 707–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, A.; Glaser, J. Zusammenhänge zwischen Tätigkeitsspielräumen und Persönlichkeitsförderung in der Arbeitstätigkeit. Z. Arb. Organ. 1991, 35, 122–136. [Google Scholar]

- Hacker, W. Allgemeine Arbeitspsychologie. Psychische Struktur und Regulation von Arbeitstätigkeiten, 2nd ed.; Huber: Bern, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rugulies, R.; Aust, B.; Madsen, I.E. Effort-reward imbalance at work and risk of depressive disorders. A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2017, 43, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndjaboué, R.; Brisson, C.; Vézina, M. Organisational justice and mental health: A systematic review of prospective studies. Occup. Environ. Med. 2012, 69, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivimäki, M.; Vahtera, J.; Elovainio, M.; Virtanen, M.; Siegrist, J. Effort-reward imbalance, procedural injustice and relational injustice as psychosocial predictors of health: Complementary or redundant models? Occup. Environ. Med. 2007, 64, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viswesvaran, C.; Sanchez, J.I.; Fisher, J. The role of social support in the process of work stress: A meta-analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 1999, 54, 314–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, P.; Spieß, E. Mit Verstand und Verständnis, Mitarbeiterorientiertes Führen und soziale Unterstützung am Arbeitsplatz; Schriftreihe der Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin: Dortmund/Berlin/Dresden, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zimber, A.; Ullrich, A.; Heidelberg, S.H. Auswirkungen kollegialer Beratung auf die Gesundheit Wie wirkt sich die Teilnahme an kollegialer Beratung auf die Gesundheit aus? Ergebnisse einer Interventionsstudie in der Psychiatriepflege Sonderdruck aus. Z. Gesundh. 2012, 19, 307–314. [Google Scholar]

- Dollard, M.F.; McTernan, W. Psychosocial safety climate: A multilevel theory of work stress in the health and community service sector. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2011, 20, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Idris, M.A.; Dollard, M. Psychosocial safety climate: Conceptual distinctiveness and effect on job demands and worker psychological health. Saf. Sci. 2012, 50, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havermans, B.M.; Boot, C.R.L.; Houtman, I.L.D.; Brouwers, E.P.M.; Anema, J.R.; van der Beek, A.J. The role of autonomy and social support in the relation between psychosocial safety climate and stress in health care workers. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genrich, M.; Worringer, B.; Angerer, P.; Müller, A. Hospital medical and nursing managers’ perspectives on health-related work design interventions. A qualitative study. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulfinger, N.; Sander, A.; Stuber, F.; Brinster, R.; Junne, F.; Limprecht, R.; Jarczok, M.N.; Seifried-Dübon, T.; Rieger, M.A.; Zipfel, S.; et al. Cluster-randomised trial evaluating a complex intervention to improve mental health and well-being of employees working in hospital—A protocol for the SEEGEN trial. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chief Physicians | Senior Physicians | Senior Nurses | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| female | 2 | 2 | 9 | 13 |

| male | 12 | 7 | 5 | 24 |

| total | 14 | 9 | 14 | 37 |

| Age range (years) | 43–60 | 38–60 | 34–60 | 34–60 |

| Mean age (years) | 51.9 | 43.6 | 47.9 | 47.8 |

| Mean number of years employed | 5.4 | 8.7 | 23.4 | 12.5 |

| Departments | Anesthesia, dermatology, gynecology, vascular surgery, cardiology/intensive care medicine, pediatrics and juvenile medicine, hospital hygiene, hand and plastic surgery, pneumology and sleep medicine, radiology, spinal surgery, vascular surgery, psychiatry, urology, and internal medicine. | Anesthesia, cardiology, neurology, pneumology and sleep medicine, spinal surgery, urology, and hand and plastic surgery. | Oncology and hematology, pediatric and youth intensive medicine, anesthesia, occupancy management, sleep laboratory, internal intensive medicine, trauma surgery, general surgery, pediatrics and youth medicine, spinal surgery, geriatrics, and psychiatry. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Worringer, B.; Genrich, M.; Müller, A.; Gündel, H.; Contributors of the SEEGEN Consortium; Angerer, P. Hospital Medical and Nursing Managers’ Perspective on the Mental Stressors of Employees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5041. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17145041

Worringer B, Genrich M, Müller A, Gündel H, Contributors of the SEEGEN Consortium, Angerer P. Hospital Medical and Nursing Managers’ Perspective on the Mental Stressors of Employees. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(14):5041. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17145041

Chicago/Turabian StyleWorringer, Britta, Melanie Genrich, Andreas Müller, Harald Gündel, Contributors of the SEEGEN Consortium, and Peter Angerer. 2020. "Hospital Medical and Nursing Managers’ Perspective on the Mental Stressors of Employees" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 14: 5041. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17145041