Understanding Physical Activity Intentions in Physical Education Context: A Multi-Level Analysis from the Self-Determination Theory

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Self-Determination Theory

1.2. The Role of Gender and PA Levels in PE

1.3. The Present Research

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Perceived Need Support

2.2.2. Need Satisfaction

2.2.3. Type of Motivation

2.2.4. Extracurricular PA Intentions

2.2.5. Out-of-school Sport Participation Status

2.3. Procedure

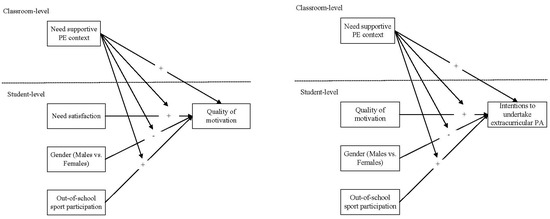

2.4. Plan of Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

3.2. Main Analyses

3.2.1. Autonomous Motivation

3.2.2. Amotivation

3.2.3. Intentions to Undertake Extracurricular PA in the Future

4. Discussion

4.1. The role of Need Satisfaction and Motivation

4.2. The Importance of Class’ Perceived Need Support

4.3. Gender Differences in Out-of-School Sport Participation

4.4. Practical Implications

4.5. Limitations and Additional Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guthold, R.; A Stevens, G.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: a pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1·6 million participants. Lancet Child Adolesc. Heal. 2019, 4642, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; McKenzie, T.L.; Beets, M.W.; Beighle, A.; Erwin, H.; Lee, S. Physical Education’s Role in Public Health: Steps Forward and Backward Over 20 Years and HOPE for the Future. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2012, 83, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Oliva, D.; Sánchez-Miguel, P.A.; Leo, F.M.; Kinnafick, F.E.; García-Calvo, T. Physical Education Lessons and Physical Activity Intentions Within Spanish Secondary Schools: A Self-Determination Perspective. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2014, 33, 232–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, I.M.; Ntoumanis, N.; Standage, M.; Spray, C.M. Motivational predictors of physical education students’ effort, exercise intentions, and leisure-time physical activity: a multilevel linear growth analysis. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2010, 32, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 1462528783. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcellos, D.; Parker, P.D.; Hilland, T.; Cinelli, R.; Owen, K.B.; Kapsal, N.; Lee, J.; Antczak, D.; Ntoumanis, N.; Ryan, R.M.; et al. Self-determination theory applied to physical education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Reeve, J.; Deci, E.L. Engaging students in learning activities: It is not autonomy support or structure but autonomy support and structure. J. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 102, 588–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cox, A.; Duncheon, N.; McDavid, L. Peers and Teachers as Sources of Relatedness Perceptions, Motivation, and Affective Responses in Physical Education. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2009, 80, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Meyer, J.; Soenens, B.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Aelterman, N.; Van Petegem, S.; Haerens, L. Do students with different motives for physical education respond differently to autonomy-supportive and controlling teaching? Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2016, 22, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haerens, L.; Aelterman, N.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Soenens, B.; Van Petegem, S. Do perceived autonomy-supportive and controlling teaching relate to physical education students’ motivational experiences through unique pathways? Distinguishing between the bright and dark side of motivation. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 16, 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, B.C.; Wang, C.J. Perceived autonomy support, behavioural regulations in physical education and physical activity intention. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2009, 10, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntoumanis, N. A Prospective Study of Participation in Optional School Physical Education Using a Self-Determination Theory Framework. J. Educ. Psychol. 2005, 97, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferriz, R. Predicting Satisfaction in Physical Education Classes: A Study Based on Self-Determination Theory. Open Educ. J. 2013, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Viira, R.; Koka, A. Participation in afterschool sport: Relationship to perceived need support, need satisfaction, and motivation in physical education. Kinesiology 2012, 44, 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, B. Outside-school physical activity participation and motivation in physical education. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 84, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L. Intrinsic motivation, extrinsic reinforcement, and inequity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1972, 22, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moller, A.C.; Deci, E.L.; Elliot, A.J. Person-Level Relatedness and the Incremental Value of Relating. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 36, 754–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sánchez-Oliva, D.; Leo, F.M.; Amado, D.; Cuevas, R.; García-Calvo, T. Desarrollo y validación del cuestionario de apoyo a las necesidades psicológicas básicas en educación física [Development and validation of the questionnarie of basic psychological need support in physical education]. Mot. Eur. J. Hum. Mov. 2013, 30, 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, J.A.; González-Cutre, D.; Chillon, M.; Parra, N. Adaptación a la educación física de la escala de las necesidades psicológicas básicas en el ejercicio [Adaptation of the basic psychological needs in exercise scale to physical education]. Rev. Mex. Psicol. 2008, 25, 295–303. [Google Scholar]

- Vlachopoulos, S.P.; Michailidou, S. Development and Initial Validation of a Measure of Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness in Exercise: The Basic Psychological Needs in Exercise Scale. Meas. Phys. Educ. Exerc. Sci. 2006, 10, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Oliva, D.; Amado, D.; Leo, F.M.; González-Ponce, I.; García-Calvo, T. Desarrollo de un cuestionario para valorar la motivación en educación física [Development of a questionnaire to assess the motivation in physical education]. Rev. Iberoam. Psicol. Del. Ejerc y el Deport. 2012, 7, 227–250. [Google Scholar]

- Ntoumanis, N. A self-determination approach to the understanding of motivation in physical education. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 71, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raudenbush, S.W.; Bryk, A.S.; Congdon, R. HLM 6 for Windows [Computer software], Scientific Software International, Inc.: Lincolnwood, IL, USA, 2004.

- Maas, C.J.; Hox, J. Sufficient Sample Sizes for Multilevel Modeling. J. Res. Methods Behav. Soc. Sci. 2005, 1, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.D. The Trans-Contextual Model of Autonomous Motivation in Education: Conceptual and Empirical Issues and Meta-Analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2016, 86, 360–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Taylor, I.M.; Lonsdale, C. Cultural differences in the relationships among autonomy support, psychological need satisfaction, subjective vitality, and effort in British and Chinese physical education. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2010, 32, 655–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mouratidis, A.A.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Sideridis, G.; Lens, W. Vitality and interest–enjoyment as a function of class-to-class variation in need-supportive teaching and pupils’ autonomous motivation. J. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 103, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global InfoBase. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho (accessed on 1 November 2012).

- Haerens, L.; Aelterman, N.; Berghe, L.V.D.; De Meyer, J.; Soenens, B.; Vansteenkiste, M. Observing physical education teachers’ need-supportive interactions in classroom settings. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2013, 35, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender (males vs. females) | - | ||||||

| 2. Out-of-school sport participation | –0.27 ** | - | |||||

| 3. Perceived need support | –0.01 | 0.05 | - | ||||

| 4. Need satisfaction | –0.10 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.67 ** | - | |||

| 5. Autonomous motivation | –0.17 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.59 ** | 0.70 ** | - | ||

| 6. Amotivation | 0.00 | –0.12 ** | –0.31 ** | –0.39 ** | –0.48 ** | - | |

| 7. Intentions to undertake extracurricular PA | –0.18 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.51 ** | –0.31 ** | - |

| M | 0.56 | 0.69 | 4.23 | 4.03 | 4.22 | 1.71 | 4.17 |

| SD | 0.50 | 0.46 | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.76 | 0.85 | 1.14 |

| Fixed Effects | Autonomous Motivation | Amotivation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | (SE) | Coefficient | (SE) | ||

| Intercept, | γ000 | 4.25 | (0.05) | 1.81 | (0.07) |

| Student-level predictors | |||||

| Gender (males vs. females) | γ100 | −0.12 ** | (0.04) | −0.08 | (0.06) |

| Out-of-school sport participation status, | γ200 | 0.12 * | (0.05) | −0.07 | (0.06) |

| Need satisfaction | γ300 | 0.70 ** | (0.03) | −0.42 ** | (0.05) |

| Classroom-level predictors | |||||

| Need supportive classroom | γ010 | 0.5305 | (0.27) | −0.11 | (0.19) |

| Student-level X class-level interactions | |||||

| Need supportive classroom X Gender | γ110 | 0.67 ** | (0.17) | 0.5506 | (0.29) |

| Need supportive classroom X Out-of-school sport participation status | γ210 | 0.04 | (0.25) | 0.14 | (0.17) |

| Need supportive classroom X Need satisfaction | γ310 | −0.2407 | (0.13) | 0.44 * | (0.17) |

| Random effects | |||||

| Intercept | r0j | 0.05 ** | 0.01 ** | ||

| Out-of-school sport participation status slope | r2j | 0.01 * | - | ||

| Need satisfaction slope | r3j | 0.03 ** | 0.05 ** | ||

| Intercept −Need supportive classroom slope | u00 | - | 0.06 ** | ||

| Gender − Need supportive slope | u10 | - | 0.04 ** | ||

| Student-level variance | εij | 0.24 | 0.53 | ||

| Fixed Effects | Intentions to Undertake Extracurricular PA | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | (SE) | ||

| Intercept, | γ000 | 3.84 | (0.09) |

| Student-level predictors | |||

| Gender (males vs. females) | γ100 | –0.16 * | (0.07) |

| Out-of-school sport participation | γ200 | 0.60 ** | (0.09) |

| Autonomous motivation | γ300 | 0.58 ** | (0.05) |

| Amotivation | γ400 | –0.10 ** | (0.04) |

| Classroom-level predictors | |||

| Need supportive classroom | γ010 | 0.73 | (0.44) |

| Student-level X class-level interactions | |||

| Need supportive classroom X Gender | γ110 | –0.19 | (0.44) |

| Need supportive classroom X out-of-school sport participation status | γ210 | 0.24 | (0.43) |

| Need supportive classroom X Autonomous Motivation | γ310 | 0.23 | (0.26) |

| Need supportive classroom X Amotivation | γ410 | 0.41 * | (0.20) |

| Random effects | |||

| Intercept | r0j | 0.20 ** | |

| Out-of-school sport participation status slope | r2j | 0.24 ** | |

| Autonomous motivation slope | r3j | 0.11 ** | |

| Student-level variance | εij | 0.77 | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sánchez-Oliva, D.; Mouratidis, A.; Leo, F.M.; Chamorro, J.L.; Pulido, J.J.; García-Calvo, T. Understanding Physical Activity Intentions in Physical Education Context: A Multi-Level Analysis from the Self-Determination Theory. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 799. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17030799

Sánchez-Oliva D, Mouratidis A, Leo FM, Chamorro JL, Pulido JJ, García-Calvo T. Understanding Physical Activity Intentions in Physical Education Context: A Multi-Level Analysis from the Self-Determination Theory. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(3):799. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17030799

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez-Oliva, David, Athanasios Mouratidis, Francisco M. Leo, José L. Chamorro, Juan J. Pulido, and Tomás García-Calvo. 2020. "Understanding Physical Activity Intentions in Physical Education Context: A Multi-Level Analysis from the Self-Determination Theory" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 3: 799. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17030799