Impact of Rowing Training on Quality of Life and Physical Activity Levels in Female Breast Cancer Survivors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Intervention

- Initial phase: mobility, proprioceptive, and postural control exercises. Main phase with rowing training. Final phase with stretching. Börg scale 5–6.

- Intermediate phase: mobility, proprioceptive, and postural control exercises. Main phase with rowing training. Final phase with stretching. Börg scale 6–7.

- Final phase: mobility, proprioceptive, and postural control exercises. Main phase with rowing training. Final phase with stretching. Börg scale 7–8.

- Initial phase—performed with warm-up, mobility, proprioceptive, and postural control exercises; all exercises carried out in a multipurpose room (10–15 min).

- Intermediate phase—performed in the Mediterranean Sea near the port of Malaga (Cruise Terminal/Malagueta Beach) using fixed-bench boats, typical of the Spanish Mediterranean, called Llauts, which are propelled by eight rowers and a coxswain or skipper [53], with each rower holding a single oar (40–60 min).

- Final phase—flexibility exercises to relax the musculature and bring the body back to its initial state after exercise (10–15 min).

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization Fact Sheets: Cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Cancer Today. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/home (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- World Health Organization Breast Cancer: Prevention and Control. Available online: https://www.who.int/cancer/detection/breastcancer/en/ (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sociedad Española de Oncología Médica Las Cifras del Cáncer en España 2020. Available online: https://seom.org/dmcancer/cifras-del-cancer/ (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- World Health Organization Early Cancer Diagnosis Saves Lives Cuts Treatments Costs. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news/item/03-02-2017-early-cancer-diagnosis-saves-lives-cuts-treatment-costs (accessed on 5 December 2020).

- Loria Calderon, T.M.; Carmona Gómez, C.D. Efecto agudo del baile como ejercicio aeróbico sobre el balance estático en personas mayores de 50 años. Rev. Iberoam. Ciencias Act. Física Deport. 2020, 9, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Cabello, A.; Pardos-Mainer, E.; González-Gálvez, N.; Sagarra-Romero, L. Actividad Física y Calidad de Vida en las Personas Mayores: Estudio Piloto PQS. Rev. Iberoam. Ciencias Act. Fis. Deport. 2018, 8, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Warburton, D.E.R.; Bredin, S.S.D. Health benefits of physical activity: A systematic review of current systematic reviews. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2017, 32, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gálvez Fernández, I. Pérdida de Peso y Masa Grasa con Auto-Cargas en Mujeres. Rev. Iberoam. Ciencias Act. Física Deport. 2017, 6, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, J.; Muñoz, D.; Cordero, J.C.; Robles, M.C.; Courel-Ibañez, J.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J. Estado de Ánimo y Calidad de Vida en Mujeres Adultas practicantes de Pádel. Rev. Iberoam. Ciencias Act. Fis. Deport. 2018, 8, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF); American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR). Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer: A Global Perspective; World Cancer Research Fund International: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 9781912259465. [Google Scholar]

- Pollán, M.; Casla-Barrio, S.; Alfaro, J.; Esteban, C.; Segui-Palmer, M.A.; Lucia, A.; Martín, M. Exercise and cancer: A position statement from the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2020, 22, 1710–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmidt, M.E.; Chang-Claude, J.; Vrieling, A.; Seibold, P.; Heinz, J.; Obi, N.; Flesch-Janys, D.; Steindorf, K. Association of pre-diagnosis physical activity with recurrence and mortality among women with breast cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2013, 133, 1431–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsson, A.; Broberg, P.; Krüger, U.; Johnsson, A.; Tornberg, Å.B.; Olsson, H. Physical activity and survival following breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2019, 28, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, K.P.; McTiernan, A. The role of physical activity in breast and gynecologic cancer survivorship. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 149, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascherini, G.; Tosi, B.; Giannelli, C.; Grifoni, E.; Degl’Innocenti, S.; Galanti, G. Breast cancer: Effectiveness of a one-year unsupervised exercise program. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2018, 59, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavala-González, J.; Gálvez-Fernández, I.; Mercadé-Melé, P.; Fernández-García, J.C. Rowing training in breast cancer survivors: A longitudinal study of physical fitness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furmaniak, A.; Menig, M.; Markes, M. Exercise for women receiving adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, M.C.; Wörner, E.A.; Verlaan, D.; van Leeuwen, P.A.M. The Mechanisms and Effects of Physical Activity on Breast Cancer. Clin. Breast Cancer 2017, 17, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courneya, K.S.; McKenzie, D.C.; Mackey, J.R.; Gelmon, K.; Friedenreich, C.M.; Yasui, Y.; Reid, R.D.; Cook, D.; Jespersen, D.; Proulx, C.; et al. Effects of Exercise Dose and Type During Breast Cancer Chemotherapy: Multicenter Randomized Trial. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013, 105, 1821–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mishra, S.I.; Scherer, R.W.; Snyder, C.; Geigle, P.; Gotay, C. Are Exercise Programs Effective for Improving Health-Related Quality of Life Among Cancer Survivors? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2014, 41, E326–E342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Di Blasio, A.; Morano, T.; Cianchetti, E.; Gallina, S.; Bucci, I.; Di Santo, S.; Tinari, C.; Di Donato, F.; Izzicupo, P.; Di Baldassarre, A.; et al. Psychophysical health status of breast cancer survivors and effects of 12 weeks of aerobic training. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2017, 27, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiskemann, J.; Schmidt, M.E.; Klassen, O.; Debus, J.; Ulrich, C.M.; Potthoff, K.; Steindorf, K. Effects of 12-week resistance training during radiotherapy in breast cancer patients. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sport. 2016, 27, 1500–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soriano-Maldonado, A.; Carrera-Ruiz, Á.; Díez-Fernández, D.M.; Esteban-Simón, A.; Maldonado-Quesada, M.; Moreno-Poza, N.; García-Martínez, M.D.M.; Alcaraz-García, C.; Vázquez-Sousa, R.; Moreno-Martos, H.; et al. Effects of a 12-week resistance and aerobic exercise program on muscular strength and quality of life in breast cancer survivors: Study protocol for the EFICAN randomized controlled trial. Medicine 2019, 98, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dieli-Conwright, C.M.; Courneya, K.S.; Demark-Wahnefried, W.; Sami, N.; Lee, K.; Sweeney, F.C.; Stewart, C.; Buchanan, T.A.; Spicer, D.; Tripathy, D.; et al. Aerobic and resistance exercise improves physical fitness, bone health, and quality of life in overweight and obese breast cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res. 2018, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.A.; Cartmel, B.; Harrigan, M.; Fiellin, M.; Capozza, S.; Zhou, Y.; Ercolano, E.; Gross, C.P.; Hershman, D.; Ligibel, J.; et al. The effect of exercise on body composition and bone mineral density in breast cancer survivors taking aromatase inhibitors. Obesity 2017, 25, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.W.; Lee, I.; Kim, J.I.; Park, H.; Lee, J.D.; Uhm, K.E.; Hwang, J.H.; Lee, E.S.; Jung, S.Y.; Park, Y.H.; et al. Factors associated with physical activity of breast cancer patients participating in exercise intervention. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 1747–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhm, K.E.; Yoo, J.S.; Chung, S.H.; Lee, J.D.; Lee, I.; Kim, J.I.; Lee, S.K.; Nam, S.J.; Park, Y.H.; Lee, J.Y.; et al. Effects of exercise intervention in breast cancer patients: Is mobile health (mHealth) with pedometer more effective than conventional program using brochure? Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017, 161, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, T.M.; Broomhall, C.N.; Crecelius, A.R. Physical and Psychological Effects of a 12-Session Cancer Rehabilitation Exercise Program. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 20, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Luca, V.; Minganti, C.; Borrione, P.; Grazioli, E.; Cerulli, C.; Guerra, E.; Bonifacino, A.; Parisi, A. Effects of concurrent aerobic and strength training on breast cancer survivors: A pilot study. Public Health 2016, 136, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, S.R. Were all in the same boat: A review of the benefits of dragon boat racing for women living with breast cancer. Evidence Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 2012, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McDonough, M.H.; Patterson, M.C.; Weisenbach, B.B.; Ullrich-French, S.; Sabiston, C.M. The difference is more than floating: Factors affecting breast cancer survivors’ decisions to join and maintain participation in dragon boat teams and support groups. Disabil. Rehabil. 2018, 41, 1788–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, A.J.; Saxton, H.R.; Kauffeldt, K.D.; Sabiston, C.M.; Tomasone, J.R. “We’re all in the same boat together”: Exploring quality participation strategies in dragon boat teams for breast cancer survivors. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, D.C. Abreast in a boat—A race against breast cancer. CMAJ 1998, 159, 376–378. [Google Scholar]

- Asensio-García, M.d.R.; Tomás-Rodríguez, M.I.; Palazón-Bru, A.; Hernández-Sánchez, S.; Nouni-García, R.; Romero-Aledo, A.L.; Gil-Guillén, V.F. Effect of rowing on mobility, functionality, and quality of life in women with and without breast cancer: A 4-month intervention. Support. Care Cancer 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacorossi, L.; Gambalunga, F.; Molinaro, S.; De Domenico, R.; Giannarelli, D.; Fabi, A. The effectiveness of the sport “dragon boat racing” in reducing the risk of lymphedema incidence: An observational study. Cancer Nurs. 2019, 42, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.; Mandal, M.; Syamal, A.K.; Majumdar, P. Monitoring Changes of Cardio-Respiratory Parameters During 2000m Rowing Performance. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2019, 12, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yoshiga, C.C.; Higuchi, M. Rowing performance of female and male rowers. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2003, 13, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNeely, M.L.; Campbell, K.L.; Courneya, K.S.; Mackey, J.R. Effect of acute exercise on upper-limb volume in breast cancer survivors: A pilot study. Physiother. Canada 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ray, H.; Jakubec, S.L. Nature-based experiences and health of cancer survivors. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2014, 20, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sablston, C.M.; McDonough, M.H.; Crocker, P.R.E. Psychosocial experiences of breast cancer survivors involved in a dragon boat program: Exploring links to positive psychological growth. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2007, 29, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadd, V.; Sabiston, C.M.; McDonough, M.H.; Crocker, P.R.E. Sources of stress for breast cancer survivors involved in dragon boating: Examining associations with treatment characteristics and self-esteem. J. Women’s Heal. 2010, 19, 1345–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonough, M.H.; Sabiston, C.M.; Ullrich-French, S. The development of social relationships, social support, and posttraumatic growth in a dragon boating team for breast cancer survivors. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2011, 33, 627–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández Sampieri, R.; Fernández Collado, C.; Baptista Lucio, P. Metodología de la Investigación, 6th ed.; Editorial McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4562-2396-0. [Google Scholar]

- Harriss, D.; Macsween, A.; Atkinson, G. Standards for Ethics in Sport and Exercise Science Research. Int. J. Sports Med. 2017, 38, 1126–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Ebihara, A. World medical association declaration of Helsinki. Jpn. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000, 28, 983–986. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera, R. Cuestionario Internacional de actividad física (IPAQ). Rev. Enfermería Trab. 2017, 7, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kathleen, Y.; Wolin, D.; Heil, S.; Charles, E.; Gary, G. Validation of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Among Blacks. J Phys Act Heal. 2008, 5, 746–760. [Google Scholar]

- Cleland, C.; Ferguson, C.; Ellis, C.; Hunter, R. Validity of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) for assessing moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and sedentary behaviour of older adults in the United Kingdom. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018, 18, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kurtze, N.; Rangul, V.; Hustvedt, B.E. Reliability and validity of the international physical activity questionnaire in the Nord-Trøndelag health study (HUNT) population of men. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Börg, G. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1982, 14, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavala-González, J. Las Modalidades del Remo: El Remo en Banco Fijo. Available online: http://tv.us.es/las-modalidades-del-remo-el-remo-en-banco-fijo/ (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Fritz, C.O.; Morris, P.E.; Richler, J.J. Effect size estimates: Current use, calculations, and interpretation. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2012, 141, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patsou, E.D.; Alexias, G.D.; Anagnostopoulos, F.G.; Karamouzis, M.V. Effects of physical activity on depressive symptoms during breast cancer survivorship: A meta-analysis of randomised control trials. ESMO Open 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Panchik, D.; Masco, S.; Zinnikas, P.; Hillriegel, B.; Lauder, T.; Suttmann, E.; Chinchilli, V.; McBeth, M.; Hermann, W. Effect of Exercise on Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema: What the Lymphatic Surgeon Needs to Know. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aramendi, J.M.G. Remo olímpico y remo tradicional: Aspectos biomecánicos, fisiológicos y nutricionales. Olympic rowing and traditional rowing: Biomechanical, physiological and nutritional aspects. Arch. Med. Deport. 2014, 31, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, K.; Jespersen, D.; Mckenzie, D.C. The effect of a whole body exercise programme and dragon boat training on arm volume and arm circumference in women treated for breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2005, 14, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintana, V.A.; Díaz, K.; Caire, G. Intervenciones para promover estilos de vida saludables y su efecto en las variables psicológicas en sobrevivientes de cáncer de mama: Revisión sistemática. Nutr. Hosp. 2018, 35, 979–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascherini, G.; Tosi, B.; Giannelli, C.; Ermini, E.; Osti, L.; Galanti, G. Adjuvant Therapy Reduces Fat Mass Loss during Exercise Prescription in Breast Cancer Survivors. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2020, 5, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolan, L.B.; Barry, D.; Petrella, T.; Davey, L.; Minnes, A.; Yantzi, A.; Marzolini, S.; Oh, P. The Cardiac Rehabilitation Model Improves Fitness, Quality of Life, and Depression in Breast Cancer Survivors. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2018, 38, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Age (Years) | 52.30 ± 3.78 | |

| Years from Diagnosis | 4.68 ± 3.00 | |

| Stage (%) | 1 | 4.54 |

| 2 | 36.36 | |

| 3 | 54.54 | |

| 4 | 4.54 | |

| Surgery (%) | Preservation | 56.53 |

| Total Mastectomy | 43.47 | |

| Variables | Mean | Percentiles | Minimum | Maximum | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 50 (Mdn) | 75 | ||||||||||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

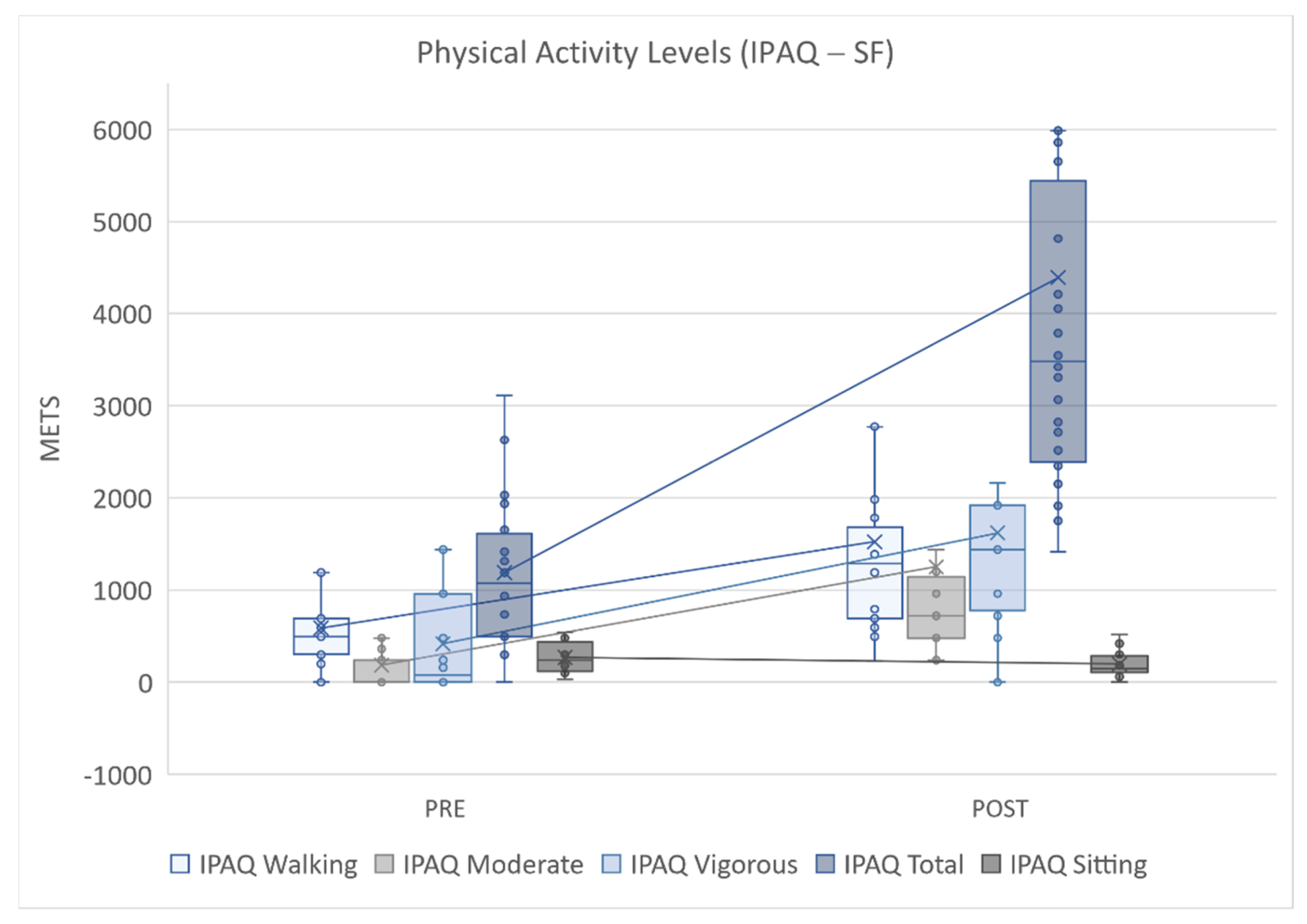

| IPAQ Walking (METS) | 587.8 ± 432.1 | 1522.1 ± 1353.1 | 305.3 | 693.0 | 495.0 | 1287.0 | 693.0 | 1683.0 | 0 | 231 | 1485 | 6930 |

| IPAQ Moderate (METS) | 185.0 ± 260.0 | 1250.0 ± 1664.2 | 0.0 | 480.0 | 0.0 | 720.0 | 240.0 | 1140.0 | 0 | 240 | 960 | 8400 |

| IPAQ Vigorous (METS) | 416.7 ± 513.1 | 1620.0 ± 1608.0 | 0.0 | 780.0 | 80.0 | 1440.0 | 960.0 | 1920.0 | 0 | 0 | 1440 | 7680 |

| IPAQ Total (METS) | 1189.5 ± 835.0 | 4392.1 ± 3341.7 | 495.0 | 2388.0 | 1075.5 | 3483.0 | 1611.0 | 5442.7 | 0 | 1413 | 3108 | 16290 |

| IPAQ Sitting (METS) | 267.8 ± 155.4 | 197.8 ± 135.2 | 120.0 | 104.3 | 240.0 | 150.0 | 435.0 | 285.0 | 30 | 0 | 540 | 520 |

| Physical Function (Points) | 75.4 ± 18.8 | 85.2 ± 13.3 | 70.0 | 77.5 | 82.5 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 93.8 | 30 | 50 | 95 | 100 |

| Physical Role (Points) | 62.5 ± 26.2 | 76.6 ± 25.4 | 37.5 | 62.5 | 71.9 | 84.4 | 85.9 | 100.0 | 6.3 | 12.5 | 100 | 100 |

| Bodily Pain (Points) | 49.7 ± 18.6 | 59.3 ± 22.2 | 41.0 | 43.5 | 51.5 | 61.0 | 62.0 | 72.0 | 10 | 22 | 84 | 100 |

| General Health (Points) | 60.1 ± 17.6 | 67.1 ± 19.9 | 46.3 | 50.5 | 61.0 | 72.0 | 72.0 | 85.8 | 20 | 30 | 92 | 97 |

| Vitality (Points) | 50.0 ± 12.9 | 59.8 ± 13.4 | 45.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 70.0 | 20 | 25 | 70 | 80 |

| Social Function (Points) | 72.4 ± 22.7 | 87.5 ± 18.4 | 62.5 | 75.0 | 75.0 | 100.0 | 87.5 | 100.0 | 12.5 | 37.5 | 100 | 100 |

| Emotional Role (Points) | 76.0 ± 15.8 | 89.9 ± 14.7 | 62.5 | 77.1 | 75.0 | 100.0 | 89.6 | 100.0 | 50 | 50 | 100 | 100 |

| Mental Health (Points) | 58.8 ± 13.9 | 67.0 ± 11.9 | 48.0 | 56.0 | 58.0 | 68.0 | 71.0 | 76.0 | 32 | 36 | 84 | 84 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gavala-González, J.; Torres-Pérez, A.; Fernández-García, J.C. Impact of Rowing Training on Quality of Life and Physical Activity Levels in Female Breast Cancer Survivors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7188. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph18137188

Gavala-González J, Torres-Pérez A, Fernández-García JC. Impact of Rowing Training on Quality of Life and Physical Activity Levels in Female Breast Cancer Survivors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(13):7188. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph18137188

Chicago/Turabian StyleGavala-González, Juan, Amanda Torres-Pérez, and José Carlos Fernández-García. 2021. "Impact of Rowing Training on Quality of Life and Physical Activity Levels in Female Breast Cancer Survivors" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 13: 7188. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph18137188