Improvement of Workplace Environment That Affects Motivation of Japanese Dental Hygienists

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Method

2.2. Questionnaire

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Survey

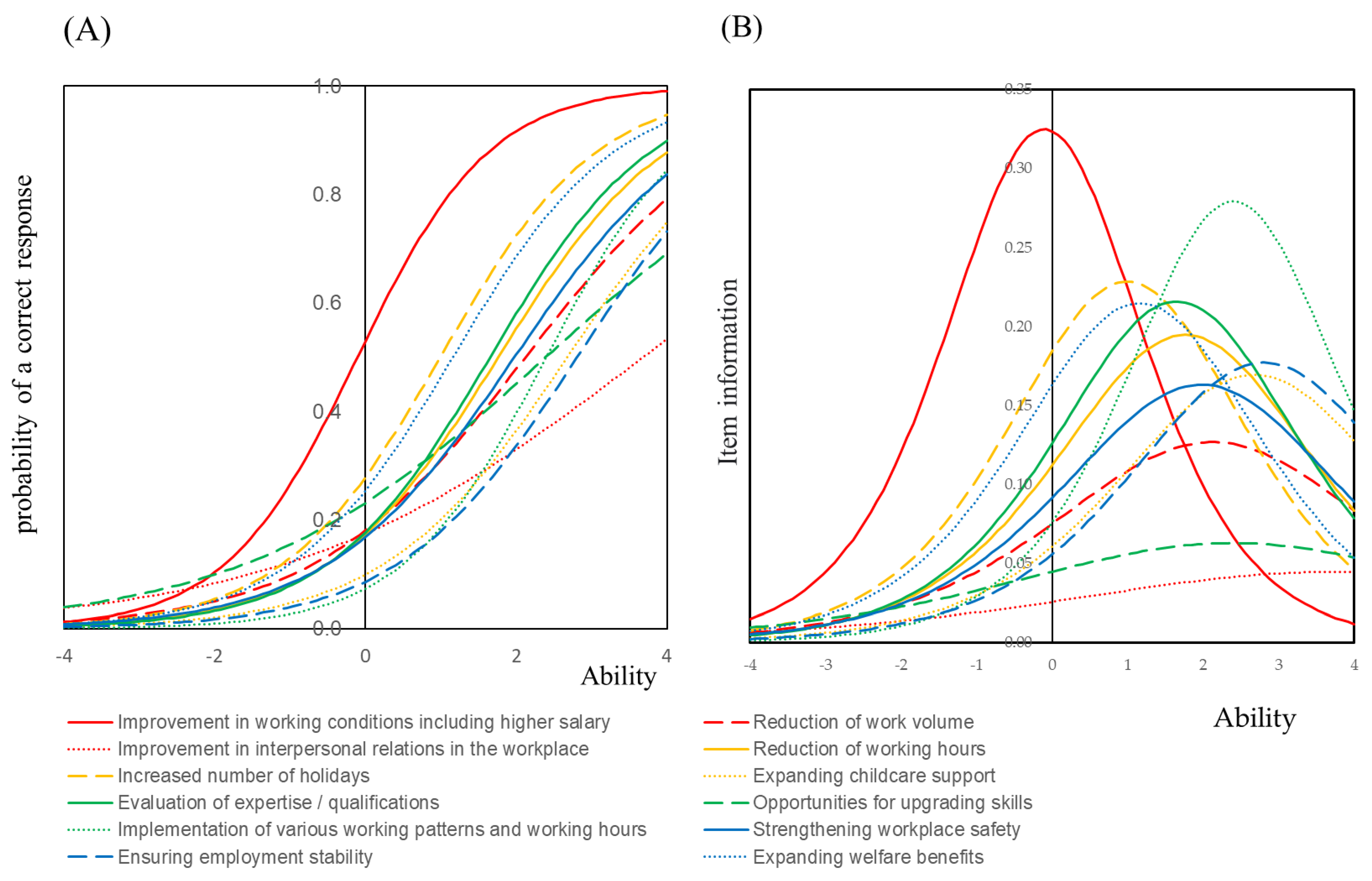

3.2. Item Response Theory (IRT) Analysis for the Items of Japanese Dental Hygienists Wish to Improve

3.3. Motivation of Japanese Dental Hygienists and Improvement of Working Conditions

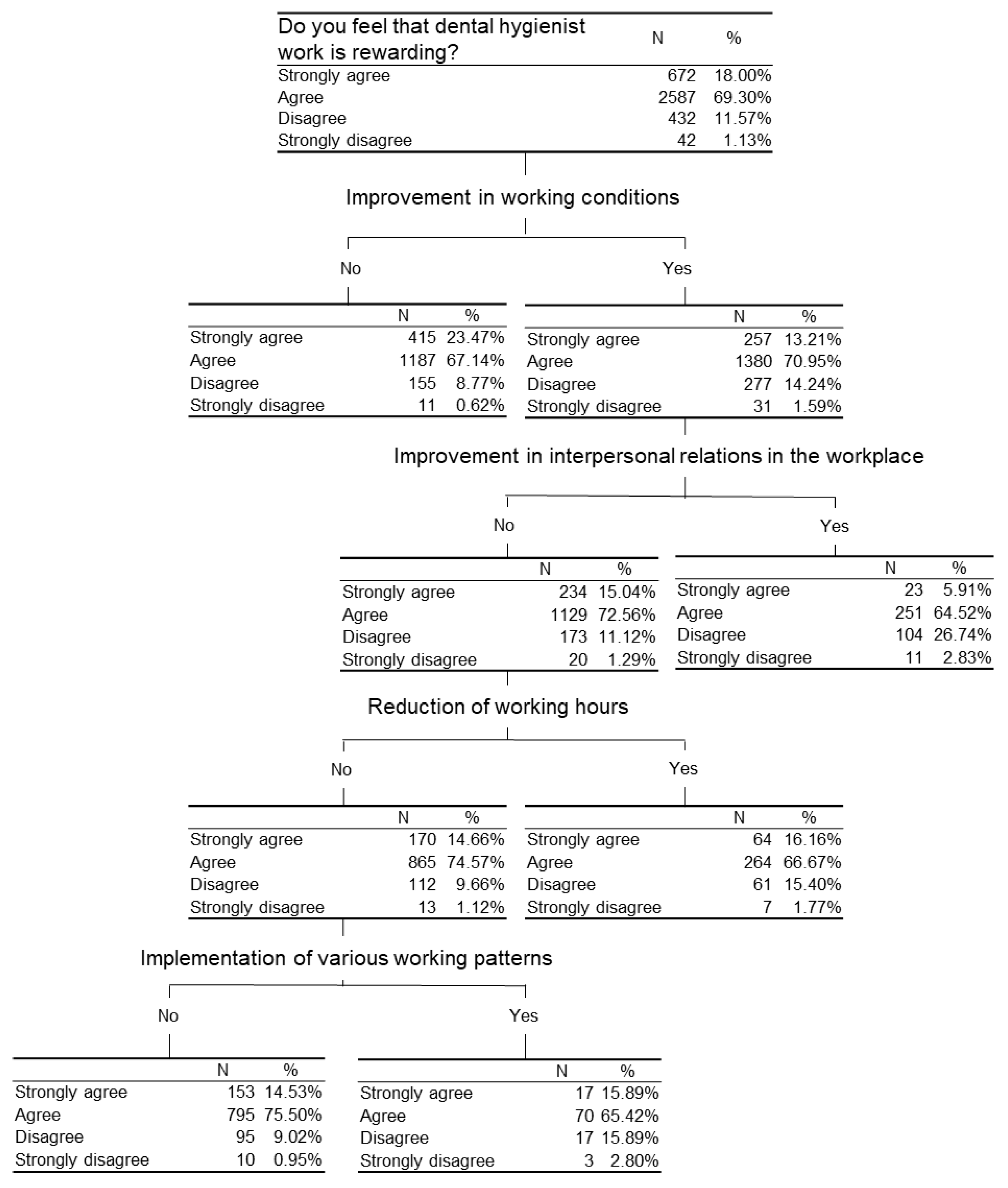

3.4. Structure of Improvement of Working Environment and Motivation

3.5. The Characteristics of the Dental Hygienists’ Unprofitable Job

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statistical Handbook of Japan 2020, Statistics Bureau, Japan. Available online: https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/handbook/c0117.html (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Kanazawa, N. Prospects and Subjects of Dental Hygienists−Aiming at the Coordination with Medical Care and Elderly Care. Ann. Jpn. Prosthodont. Soc. 2014, 6, 267–272. Available online: https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jodu/51/2/51_99/_pdf (accessed on 1 February 2021). [CrossRef]

- Shiraishi, A.; Yoshimura, Y.; Wakabayashi, H.; Tsuji, Y.; Yamaga, M.; Koga, H. Hospital dental hygienist intervention improves activities of daily living, home discharge and mortality in post-acute rehabilitation. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2018, 19, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsubara, C.; Shirobe, M.; Furuya, J.; Watanabe, Y.; Motokawa, K.; Edahiro, A.; Ohara, Y.; Awata, S.; Kim, H.; Fujiwara, Y.; et al. Effect of oral health intervention on cognitive decline in community-dwelling elderly subjects: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2021, 92, 104267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, C.M. Dental Hygiene Intervention to Prevent Nosocomial Pneumonias. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2014, 14, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebib, N.; Cuvelier, C.; Malézieux-Picard, A.; Parent, T.; Roux, X.; Fassier, T.; Müller, F.; Prendki, V. Pneumonia prevention in the elderly patients: The other sides. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Report on Public Health Administration and Services: Number of Active Dental Hygienists and Dental Technicians in Japan; Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare: Tokyo, Japan, 2014. Available online: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/eisei/14/dl/gaikyo.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2020). (in Japanese)

- Japan Dental Hygienists’ Association. Reports of Actual Working Condition of Dental Hygienists. 2014. Available online: https://www.jdha.or.jp/pdf/outline/h27-dh_hokoku.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2020). (In Japanese).

- Badubi, R.M. Theories of Motivation and Their Application in Organizations: A Risk Analysis. Int. J. Innov. Econ. Dev. 2017, 3, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vick, B. Career satisfaction of Pennsylvanian dentists and dental hygienists and their plans to leave direct patient care. J. Public Health Dent. 2015, 76, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbons, D.E.; Corrigan, M.J.; Newton, J.T. A national survey of dental hygienists: Working patterns and job satisfaction. Br. Dent. J. 2001, 190, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buunk-Werkhoven, Y.A.B.; Hollaar, V.R.; Jongbloed-Zoet, C. Work engagement among Dutch dental hygienists. J. Public Health Dent. 2014, 74, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akesson, I.; Balogh, I.; Hansson, G.-Å. Physical workload in neck, shoulders and wrists/hands in dental hygienists during a work-day. Appl. Ergon. 2012, 43, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lietz, J.; Kozak, A.; Nienhaus, A. Prevalence and occupational risk factors of musculoskeletal diseases and pain among dental professionals in Western countries: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, M.-J.; Kim, H.-S.; Lim, C.-Y. Effects of Dental Hygienists Job Stress on Somatization in an Area. J. Dent. Hyg. Sci. 2020, 20, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, Y.; Okada, A.; Miyoshi, J.; Mukaida, M.; Akasaka, E.; Saigo, K.; Daikoku, H.; Maekawa, H.; Sato, T.; Hanada, N. Willingness to Work and the Working Environment of Japanese Dental Hygienists. Int. J. Dent. 2018, 2018, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nomura, Y.; Okada, A.; Yamamoto, Y.; Kakuta, E.; Tomonari, H.; Hosoya, N.; Hanada, N.; Yoshida, N.; Takei, N. Factors Behind Leaving the Job and Rejoining it by the Japanese Dental Hygienist. Open Dent. J. 2020, 14, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S.W.D.; Ross, M.K.; Ibbetson, R.J. Job satisfaction among dually qualified dental hygienist-therapists in UK primary care: A structural model. Br. Dent. J. 2011, 210, E5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S.W.D.; Ross, M.K.; Ibbetson, R.J. Dental hygienists and therapists: How much professional autonomy do they have? How much do they want? Results from a UK survey. Br. Dent. J. 2011, 210, E16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jin, K.; Nakatsuka, M.; Maesoma, A.; Wato, M.; Uene, M.; Doi, T.; Kataoka, K.; Miyake, T.; Komasa, Y. Employment status of dental hygienists. J. Osaka Dent. Univ. 2017, 51, 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Usui, Y.; Miura, H. Workforce re-entry for Japanese unemployed dental hygienists. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2014, 13, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candell, A.; Engström, M. Dental hygienists’ work environment: Motivating, facilitating, but also trying. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2009, 8, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkawi, Z.A. Career satisfaction of Jordanian dental hygienists. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2015, 14, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, Y.; Kakuta, E.; Okada, A.; Yamamoto, Y.; Tomonari, H.; Hosoya, N.; Hanada, N.; Yoshida, N.; Takei, N. Prioritization of the Skills to Be Mastered for the Daily Jobs of Japanese Dental Hygienists. Int. J. Dent. 2020, 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noh, S.M.; Lim, H.J.; Kim, M.H.; Lim, D.S. Factors Affecting the Turnover Intention of Dental Hygienists: Emotional Labor, Job Satisfaction, and Social Support. J. Dent. Hyg. Sci. 2018, 18, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Naughton, D.K. Expanding Oral Care Opportunities: Direct Access Care Provided by Dental Hygienists in the United States. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2014, 14, 171–182.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catlett, A. Attitudes of Dental Hygienists towards Independent Practice and Professional Autonomy. J. Dent. Hyg. 2016, 90, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Department of the Treasury, Internal Revenue Service. 2019 Instructions for Schedule C. Available online: https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-prior/i1040sc--2019.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Muroga, R.; Tsuruta, J.; Morio, I. Disparity in perception of the working condition of dental hygienists between dentists and dental hygiene students in Japan. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2015, 13, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/dental-hygienists.htm (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Calley, K.H.; Hodges, K.O.; Johnson, R. Prioritization of professional issues by Idaho Dental Hygienists. J. Dent. Hyg. 2001, 75, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kruger, E.; Smith, K.; Tennant, M. Dental therapy in Western Australia: Profile and perceptions of the workforce. Aust. Dent. J. 2006, 51, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hopcraft, M.; McNally, C.M.; Ng, C.; Pek, L.; Pham, T.; Phoon, W.; Poursoltan, P.; Yu, W. Working practices and job satisfaction of Victorian dental hygienists. Aust. Dent. J. 2008, 53, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.K. Job satisfaction among dental therapists in South Africa. J. Public Health Dent. 2012, 74, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, T.; Yamazaki, Y. Relationship between work-family conflict and a sense of coherence among Japanese registered nurses. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2010, 7, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Inoue, T.; Harada, H.; Oike, M. Job control, work-family balance and nurses’ intention to leave their profession and organization: A comparative cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 64, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gök, A.U.; Kocaman, G. Reasons for leaving nursing: A study among Turkish nurses. Contemp. Nurse 2011, 39, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slabbert, M.; Pienaar, B. Using a Locum Tenens in a Private Practice. PELJ/PER 2014, 16, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferguson, J.; Walshe, K. The quality and safety of locum doctors: A narrative review. J. R. Soc. Med. 2019, 112, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, A.N.; Miller, P. Locum Tenens Staffing and Billing Considerations. J. Med. Pract. Manag. 2017, 32, 407–410. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yamamoto, Y.; Nomura, Y.; Okada, A.; Kakuta, E.; Yoshida, N.; Hosoya, N.; Hanada, N.; Takei, N. Improvement of Workplace Environment That Affects Motivation of Japanese Dental Hygienists. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1309. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph18031309

Yamamoto Y, Nomura Y, Okada A, Kakuta E, Yoshida N, Hosoya N, Hanada N, Takei N. Improvement of Workplace Environment That Affects Motivation of Japanese Dental Hygienists. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(3):1309. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph18031309

Chicago/Turabian StyleYamamoto, Yuko, Yoshiaki Nomura, Ayako Okada, Erika Kakuta, Naomi Yoshida, Noriyasu Hosoya, Nobuhiro Hanada, and Noriko Takei. 2021. "Improvement of Workplace Environment That Affects Motivation of Japanese Dental Hygienists" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 3: 1309. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph18031309