Cancer Survivors in Saint Lucia Deeply Value Social Support: Considerations for Cancer Control in Under-Resourced Communities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Recruitment

2.2. Data Collection and Questionnaire

2.3. Variables and Definitions

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

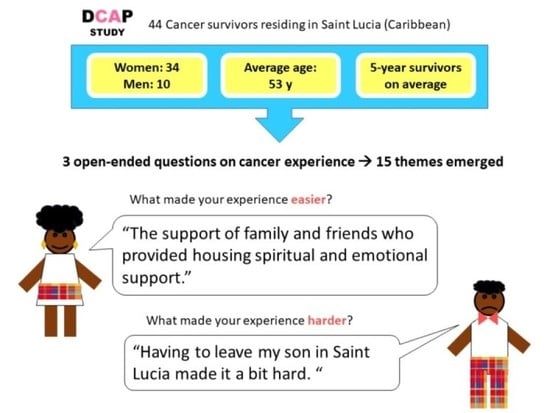

3.1. Characteristics of Cancer Survivors

3.2. Thematic Analysis of Patient Experiences

3.2.1. Availability of Support Groups

3.2.2. Importance of Support from Family and Friends

3.2.3. Access to Finances

3.2.4. Health Education and Patient Navigation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ward, E.; Jemal, A.; Cokkinides, V.; Singh, G.K.; Cardinez, C.; Ghafoor, A.; Thun, M. Cancer Disparities by Race/Ethnicity and Socioeconomic Status. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2004, 54, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarfati, D.; Dyer, R.; Vivili, P.; Herman, J.; Spence, D.; Sullivan, R.; Weller, D.; Bray, F.; Hill, S.; Bates, C.; et al. Cancer control in small island nations: From local challenges to global action. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, e535–e548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferlay, J.; Ervik, M.; Lam, F.; Colombet, M.; Mery, L.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2020; Available online: http://gco.iarc.fr/today/home (accessed on 23 August 2020).

- PAHO; Ministry of Health of Saint Lucia. Pharmaceutical Situation in Saint Lucia. In WHO Assessment of Level II—Health Facilities Survey; PAHO: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- NGO Development Foundation. Faces of Cancer St. Lucia. In NGO Database; 2017; Available online: https://www.ngocaribbean.org/faces-of-cancer-st-lucia/ (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Reilly, R.; Micklem, J.; Yerrell, P.; Banham, D.; Morey, K.; Stajic, J.; Eckert, M.; Lawrence, M.; Stewart, H.B.; Brown, A.; et al. Aboriginal experiences of cancer and care coordination: Lessons from the Cancer Data and Aboriginal Disparities (CanDAD) narratives. Health Expect. 2018, 21, 927–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, E.V.; Lyford, M.; Holloway, M.; Parsons, L.; Mason, T.; Sabesan, S.; Thompson, S.C. “The support has been brilliant”: Experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients attending two high performing cancer services. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas-Purcell, K.; Tarver, W.L.; Richards, C.; Primus-Joseph, M. Gatekeepers’ perceptions of the quality and availability of services for breast and cervical cancer patients in the English-speaking Windward Islands: An exploratory investigation. Cancer Causes Control 2017, 28, 1195–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, A.; Koranteng, F. Availability, accessibility, and impact of social support on breast cancer treatment among breast cancer patients in Kumasi, Ghana: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- A Murray, S.; Grant, E.; Grant, A.; Kendall, M. Dying from cancer in developed and developing countries: Lessons from two qualitative interview studies of patients and their carers. BMJ 2003, 326, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Auguste, A.; Jones, G.; Phillip, D.; Catherine, J.S.; Dos Santos, E.; Gabriel, O.; Radix, C. Difficulties in Accessing Cancer Care in a Small Island State: A Community-Based Pilot Study of Cancer Survivors in Saint Lucia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.N.; Mosher, C.E.; Winger, J.; Abonour, R.; Kroenke, K. Cancer-related loneliness mediates the relationships between social constraints and symptoms among cancer patients. J. Behav. Med. 2018, 41, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh-Hunt, N.; Bagguley, D.; Bash, K.; Turner, V.; Turnbull, S.; Valtorta, N.; Caan, W. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health 2017, 152, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen, N.; Arieli, T. Field research in conflict environments: Methodological challenges and snowball sampling. J. Peace Res. 2011, 48, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Guest, G.; MacQueen, K.; Namey, E. Applied Thematic Analysis; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Corporation Canada (NRC). Eight Dimensions of Patient Centred Care; National Research Corporation Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas, C.; Matheson, L.; Nayoan, J.; Glaser, A.; Gavin, A.; Wright, P.; Wagland, R.; Watson, E. Ethnicity and the prostate cancer experience: A qualitative metasynthesis. Psycho-Oncology 2016, 25, 1147–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitch, M.I.; Coronado, A.C.; Schippke, J.C.; Chadder, J.; Green, E. Exploring the perspectives of patients about their care experience: Identifying what patients perceive are important qualities in cancer care. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 2299–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridge, E.; Conn, L.G.; Dhanju, S.; Singh, S.; Moody, L. The Patient Experience of Ambulatory Cancer Treatment: A Descriptive Study. Curr. Oncol. 2019, 26, e482–e493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Arditi, C.; Walther, D.; Gilles, I.; Lesage, S.; Griesser, A.-C.; Bienvenu, C.; Eicher, M.; Peytremann-Bridevaux, I. Computer-assisted textual analysis of free-text comments in the Swiss Cancer Patient Experiences (SCAPE) survey. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, M.I.; Sharp, L.; Hanly, P.; Longo, C.J. Experiencing financial toxicity associated with cancer in publicly funded healthcare systems: A systematic review of qualitative studies. J. Cancer Surviv. 2022, 16, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donkor, A.; Della Atuwo-Ampoh, V.; Yakanu, F.; Torgbenu, E.; Ameyaw, E.K.; Kitson-Mills, D.; Vanderpuye, V.; Kyei, K.A.; Anim-Sampong, S.; Khader, O.; et al. Financial toxicity of cancer care in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradian, S.; Aledavood, S.; Tabatabaee, A. Iranian cancer patients and their perspectives: A qualitative study. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2012, 21, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetharamu, N.; Iqbal, U.; Weiner, J.S. Determinants of trust in the patient–oncologist relationship. Palliat. Support. Care 2007, 5, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiba, C.F.; Zimba, C.C.; Thom, A.; Matewere, M.; Go, V.; Pence, B.; Gaynes, B.N.; Masiye, J. The role of patient-provider communication: A qualitative study of patient attitudes regarding co-occurring depression and chronic diseases in Malawi. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, S.; Greenfield, S.; Ware, J.E. Assessing the Effects of Physician-Patient Interactions on the Outcomes of Chronic Disease. Med. Care 1989, 27, S110–S127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Han, J.Y.; Shaw, B.; McTavish, F.; Gustafson, D. The Roles of Social Support and Coping Strategies in Predicting Breast Cancer Patients’ Emotional Well-being: Testing Mediation and Moderation Models. J. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leung, J.; Pachana, N.A.; McLaughlin, D. Social support and health-related quality of life in women with breast cancer: A longitudinal study. Psycho-Oncology 2014, 23, 1014–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute. Definition of Social Support—NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms—NCI. 2011. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/social-support (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- Guetterman, T.C.; Fetters, M.D.; Creswell, J.W. Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Results in Health Science Mixed Methods Research through Joint Displays. Ann. Fam. Med. 2015, 13, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cull, W.L.; O’Connor, K.G.; Sharp, S.; Tang, S.-F.S. Response Rates and Response Bias for 50 Surveys of Pediatricians. Health Serv. Res. 2005, 40, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sex, n% | ||

| Men | 10 | 22.7 |

| Women | 34 | 77.3 |

| Age at diagnosis (y) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 55 | (42–64) |

| Cancer site, n% | ||

| Breast | 25 | 56.8 |

| Female pelvis a | 8 | 18.2 |

| Prostate | 6 | 13.6 |

| Other b | 5 | 11.4 |

| Survivorship (y) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 4.2 | (1.7–7.8) |

| Missing | 1 | |

| Stage at diagnosis, n% | ||

| Early (I/II) | 24 | 61.5 |

| Advanced (III/IV) | 15 | 38.5 |

| Missing | 5 | |

| Treatment status, n% | ||

| Finished initial active treatment | 32 | 72.7 |

| Still on treatment | 8 | 18.2 |

| No treatment taken | 4 | 9.1 |

| Marital status, n% | ||

| Single | 19 | 44.2 |

| Married/Other | 24 | 55.8 |

| Missing | 1 | |

| Education level, n% | ||

| Primary | 12 | 27.9 |

| Secondary | 13 | 30.2 |

| Tertiary | 18 | 41.9 |

| Missing | 1 | |

| Private medical insurance, n% | ||

| Yes | 18 | 40.9 |

| No | 26 | 59.1 |

| Hot water at home, n% | ||

| Solar | 12 | 27.9 |

| Electric | 9 | 20.9 |

| No | 22 | 51.2 |

| Missing | 1 | |

| History of medical condition(s), n% | ||

| Yes | 21 | 47.7 |

| No | 23 | 52.3 |

| Professional status, n% | ||

| Working | 24 | 55.8 |

| Not working | 19 | 44.2 |

| Missing | 1 | |

| Treatment abroad, n% | ||

| Yes | 22 | 57.9 |

| No | 16 | 42.1 |

| Missing | 6 | |

| Diagnostic test(s) abroad, n% | ||

| Yes | 27 | 65.9 |

| No | 14 | 34.2 |

| Missing | 3 |

| Open-Ended Question | Patient n° | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Was there anything in particular that made your experience easier? | 1 | Joining Faces of Cancer Saint Lucia. |

| 2 | The support of family and friends who provided housing, spiritual and emotional support. | |

| 3 | Yes, the almighty, I trusted him to give me the strength to endure. | |

| 4 | Family support (My sister was always here), insurance (Money was not a problem), my employer supported me mentally and financially. | |

| 5 | Treatment at Tapion hospital was excellent but costly. | |

| 6 | Family support, natural medications. | |

| Was there anything in particular that made your experience harder? | 7 | Coming up with the funds, some health care providers did not give me the opportunity to share information, they don’t listen. Emotionally I could not deal with the first diagnosis. I am still paying the loans. |

| 8 | Dealing with cancer. Having no money or place to turn to. No support group available. | |

| 9 | Lack of team structure to deal with issues together. Absence of counsellors. Being discharged prematurely. | |

| 10 | Having to leave my son in Saint Lucia made it a bit hard. My son was afraid of me.I had to send him back to Saint Lucia. | |

| 11 | Having no finance to pay for treatment and the doctors would not see you if you have no money, they would rather you die. | |

| 12 | Not knowing where to go to get help in dealing with the illness. | |

| Do you have any suggestions to help improve the experience for other people in similar circumstances? | 13 | Advising on early detection exam for all types of cancer. Visits to health centres, health promotion, seek support and other medical interventions including cancer markers. |

| 14 | Having a support group with cancer patients. Having a psycho-social person attached to oncologist or hospital pre/post diagnosis. Something financial in place for persons living with cancer. Government should invest in funding cancer research and treatment because of its cost. Home care for the patients with cancer. Build a wing at the hospital just like the maternity to deal with cancer patients. Decentralise train persons in palliative care. | |

| 9 | Doctors need to come together as a team (GP, surgeon, oncologist, radiologists). Everything is done in isolation because they all want to make a fortune. The medication prescribed was not available locally and is $100 US monthly. People don’t understand the importance of health insurance. Inculcate healthy lifestyle in persons. Sensitize and educate the public. Availability of treatment needed. Never give up. Come out and let people or family know of your condition. Live a stress-free life (reduce stress level). Carers of persons with cancer ensure that they are given care. Have to support you at all times. Do your breast examination. Know your family medical history. | |

| 15 | I would like to encourage persons in similar circumstances to keep the faith and continue praying. | |

| 16 | Do whatever you need to raise funds for treatment. Listen to the health care providers and do not waste time.Do regular cancer screening. Continue or adapt healthy life styles. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Auguste, A.; Cox, S.; Oliver, J.S.; Phillip, D.; Gabriel, O.; Catherine, J.S.; Radix, C.; Luce, D.; Barul, C. Cancer Survivors in Saint Lucia Deeply Value Social Support: Considerations for Cancer Control in Under-Resourced Communities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6531. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph19116531

Auguste A, Cox S, Oliver JS, Phillip D, Gabriel O, Catherine JS, Radix C, Luce D, Barul C. Cancer Survivors in Saint Lucia Deeply Value Social Support: Considerations for Cancer Control in Under-Resourced Communities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(11):6531. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph19116531

Chicago/Turabian StyleAuguste, Aviane, Shania Cox, JoAnn S. Oliver, Dorothy Phillip, Owen Gabriel, James St. Catherine, Carlene Radix, Danièle Luce, and Christine Barul. 2022. "Cancer Survivors in Saint Lucia Deeply Value Social Support: Considerations for Cancer Control in Under-Resourced Communities" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 11: 6531. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph19116531