How Does Social Security Fairness Predict Trust in Government? The Serial Mediation Effects of Social Security Satisfaction and Life Satisfaction

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Trust in Government

2.2. Social Security Fairness and Trust in Government

2.3. The Mediator of Social Security Satisfaction

2.4. The Mediator of Life Satisfaction

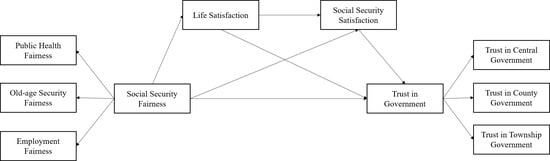

2.5. The Serial Mediation Effects of Social Security Satisfaction and Life Satisfaction

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data and Sample

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Criterion Variable

3.2.2. Predictor Variable

3.2.3. Mediator Variables

3.2.4. Control Variables

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

4.2. The Serial Mediation Effects of Social Security Satisfaction and Life Satisfaction

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vu, V. Public Trust in Government and Compliance with Policy during COVID-19 Pandemic: Empirical Evidence from Vietnam. Public Organ. Rev. 2021, 21, 779–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Schachter, H.L. Exploring the Relationship between Trust in Government and Citizen Participation. Int. J. Public Adm. 2019, 42, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.H.; Listhaug, O. Political-Parties and Confidence in Government—A Comparison of Norway, Sweden and the United-States. Br. J. Political Sci. 1990, 20, 357–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wong, T.K.Y.; Wan, P.S.; Hsiao, H.H.M. The bases of political trust in six Asian societies: Institutional and cultural explanations compared. Int. Political Sci. Rev. 2011, 32, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Dong, C.H.; Chen, Y.J. Government’s Economic Performance Fosters Trust in Government in China: Assessing the Moderating Effect of Respect for Authority. Soc. Indic. Res. 2021, 154, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. Government for Leaving No One Behind: Social Equity in Public Administration and Trust in Government. Sage Open 2021, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marien, S.; Werner, H. Fair treatment, fair play? The relationship between fair treatment perceptions, political trust and compliant and cooperative attitudes cross-nationally. Eur. J. Political Res. 2019, 58, 72–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, D.H.; Hu, W. Determinants of public trust in government: Empirical evidence from urban China. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2017, 83, 358–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeri, I.; Uster, A.; Vigoda-Gadot, E. Does Performance Management Relate to Good Governance? A Study of Its Relationship with Citizens’ Satisfaction with and Trust in Israeli Local Government. Public Perform. Manag. 2019, 42, 241–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, E.W.; Hinnant, C.C.; Moon, M.J. Linking citizen satisfaction with e-government and trust in government. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2005, 15, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meng, T.; Yang, M. Governance Performance and Political Trust in Transitional China:From “Economic Growth Legitimacy” to “Public Goods Legitimacy”. Comp. Econ. Soc. Syst. 2012, 4, 122–135. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.D.; Qin, H. Survey on Perceptions of Social Fairness and Their Implications for Social Governance Innovation. Soc. Sci. China 2018, 39, 187–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Xiao, J.J. Perceived Social Policy Fairness and Subjective Wellbeing: Evidence from China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 107, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmerli, S.; Castillo, J.C. Income inequality, distributive fairness and political trust in Latin America. Soc. Sci. Res. 2015, 52, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.K.; Lassar, W.M.; Shekhar, V. Convenience and satisfaction: Mediation of fairness and quality. Serv. Ind. J. 2016, 36, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.Q.; Chen, H.G. Service fairness and customer satisfaction in internet banking Exploring the mediating effects of trust and customer value. Internet Res. 2012, 22, 482–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Aoyagi, S. Trust in Local Government: Service Satisfaction, Culture, and Demography. Adm. Soc. 2020, 52, 1268–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.T. Intercultural Experience as an Impediment of Trust: Examining the Impact of Intercultural Experience and Social Trust Culture on Institutional Trust in Government. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 113, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanley, V.A.; Rudolph, T.J.; Rahn, W.M. The origins and consequences of public trust in government—A time series analysis. Public Opin. Quart. 2000, 64, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im, T.; Cho, W.; Porumbescu, G.; Park, J. Internet, Trust in Government, and Citizen Compliance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2014, 24, 741–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Liu, Y.Y.; Kapucu, N.; Peng, Z.C. Online media and trust in government during crisis: The moderating role of sense of security. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 50, 101717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, J.S. Springing the ‘Tacitus Trap’: Countering Chinese state-sponsored disinformation. Small Wars Insur. 2021, 32, 229–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turper, S.; Aarts, K. Political Trust and Sophistication: Taking Measurement Seriously. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 130, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mishler, W.; Rose, R. What Are the Origins of Political Trust? Testing Institutional and Cultural Theories in Post-Communist Societies. Comp. Political Stud. 2001, 34, 30–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.W. The Contextual Effects of Political Trust on Happiness: Evidence from China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 139, 491–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, K.Y.; Ye, X.F. Social security system reform in China. China Econ. Rev. 2003, 14, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.S. Inequity in Social-Exchange. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1965, 2, 267–299. [Google Scholar]

- El Akremi, A.; Vandenberghe, C.; Camerman, J. The role of justice and social exchange relationships in workplace deviance: Test of a mediated model. Hum. Relat. 2010, 63, 1687–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katok, E.; Pavlov, V. Fairness in supply chain contracts: A laboratory study. J. Oper. Manag. 2013, 31, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E.; Schmidt, K.M. A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. Q. J. Econ. 1999, 114, 817–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loch, C.H.; Wu, Y.Z. Social Preferences and Supply Chain Performance: An Experimental Study. Manag. Sci. 2008, 54, 1835–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Z.C.; Tan, X.H. Revitalization of Trust in Local Government after Wenchuan Earthquake: Constraints and Strategies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oliver, R.L. A Cognitive Model of the Antecedents and Consequences of Satisfaction Decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovsky, N.; Mok, J.Y.; Leon-Cazares, F. Citizen Expectations and Satisfaction in a Young Democracy: A Test of the Expectancy-Disconfirmation Model. Public Adm. Rev. 2017, 77, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, T.; Laegreid, P. Trust in government: The relative importance of service satisfaction, political factors, and demography. Public Perform. Manag. 2005, 28, 487–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, S.; Prilleltensky, I. Happiness as fairness: The relationship between national life satisfaction and social justice in EU countries. J. Community Psychol. 2020, 48, 1997–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.; Carleton, R.N. Subjective relative deprivation is associated with poorer physical and mental health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 147, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Pan, H.M. Investigation on Life Satisfaction of Rural-to-Urban Migrant Workers in China: A Moderated Mediation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shin, J. Relative Deprivation, Satisfying Rationality, and Support for Redistribution. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 140, 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.X.; Li, D.Y. Social capital, policy fairness, and subjective life satisfaction of earthquake survivors in Wenchuan, China: A longitudinal study based on post-earthquake survey data. Health Qual. Life Outcomes Health 2020, 18, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.K.Y.; Hsiao, H.H.M.; Wan, P.S. Comparing Political Trust in Hong Kong and Taiwan: Levels, Determinants, and Implications. Jpn. J. Political Sci. 2009, 10, 147–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helliwell, J.F.; Huang, H.F. How’s your government? International evidence linking good government and well-being. Br. J. Political Sci. 2008, 38, 595–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Headey, B.; Veenhoven, R.; Wearing, A. Top-down Versus Bottom-up Theories of Subjective Well-Being. Soc. Indic. Res. 1991, 24, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loewe, N.; Bagherzadeh, M.; Araya-Castillo, L.; Thieme, C.; Batista-Foguet, J.M. Life Domain Satisfactions as Predictors of Overall Life Satisfaction among Workers: Evidence from Chile. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 118, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Erdogan, B.; Bauer, T.N.; Truxillo, D.M.; Mansfield, L.R. Whistle while You Work: A Review of the Life Satisfaction Literature. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 1038–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachmann, B.; Sariyska, R.; Kannen, C.; Blaszkiewicz, K.; Trendafilov, B.; Andone, I.; Eibes, M.; Markowetz, A.; Li, M.; Kendrick, K.; et al. Contributing to Overall Life Satisfaction: Personality Traits Versus Life Satisfaction Variables Revisited—Is Replication Impossible? Behav. Sci. 2018, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Conway, J.M.; Lance, C.E. What Reviewers Should Expect from Authors Regarding Common Method Bias in Organizational Research. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, H.; Long, L. Statistical Remedies for Common Method Biases: Problems and Suggestions. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 12, 942–950. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dong, L.S.; Kubler, D. Sources of Local Political Trust in Rural China. J. Contemp. China 2018, 27, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.J. Political trust in rural China. Mod. China 2004, 30, 228–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.J. Cultural values and political trust—A comparison of the People’s Republic of China and Taiwan. Comp. Politics 2001, 33, 401–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.N. Outward specific trust in the balancing of hierarchical government trust: Evidence from mainland China. Br. J. Sociol. 2021, 72, 774–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickson, B.J.; Shen, M.M.; Yan, J. Generating Regime Support in Contemporary China: Legitimation and the Local Legitimacy Deficit. Mod. China 2017, 43, 123–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.C. Corruption and Perceived Fairness: Empirical Evidence from East Asian Countries. J. East Asian Stud. 2021, 21, 305–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.H.; Zhang, X.M. Structure hypothesis of authoritarian rule: Evidence from the lifespans of China’s dynasties. J. Chin. Gov. 2018, 3, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yu, X. Influence of Social Fairness on Government Trust: An Empirical Research Based on the Data of CGSS2010. Financ. Trade Res. 2017, 28, 76–84. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- De Blok, L.; Kumlin, S. Losers’ Consent in Changing Welfare States: Output Dissatisfaction, Experienced Voice and Political Distrust. Political Stud. 2021, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R. Farmers’ petition and Erosion of Political Trust in Government. Sociol. Stud. 2007, 22, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.J. The Magnitude and Resilience of Trust in the Center: Evidence from Interviews with Petitioners in Beijing and a Local Survey in Rural China. Mod. China 2013, 39, 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, S.; Wang, H.; Su, Y. How Can the Chinese People Gain a Higher Level of the Subjective Wellbeing? Based on the survey of people’s livelihood index in China. Manag. World 2015, 6, 8–21. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qian, X.Y. China’s social security response to COVID-19: Wider lessons learnt for social security’s contribution to social cohesion and inclusive economic development. Int. Soc. Secur. Rev. 2020, 73, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.F.; Zheng, Z.C.; Zhang, L.J.; Qin, Y.C.; Duan, J.R.; Zhang, A.Y. Influencing Factors of Environmental Risk Perception during the COVID-19 Epidemic in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Trust in central government | 4.492 | 0.803 | ||||||

| 2 Trust in county government | 3.745 | 1.180 | 0.403 *** | |||||

| 3 Trust in township government | 3.494 | 1.300 | 0.294 *** | 0.778 *** | ||||

| 4 Overall trust in government | 3.910 | 0.912 | 0.606 *** | 0.919 *** | 0.897 *** | |||

| 5 Social security fairness | 3.491 | 0.887 | 0.189 *** | 0.375 *** | 0.387 *** | 0.401 *** | ||

| 6 Social security satisfaction | 3.453 | 1.067 | 0.194 *** | 0.346 *** | 0.357 *** | 0.375 *** | 0.475 *** | |

| 7 Life satisfaction | 3.471 | 0.810 | 0.110 *** | 0.247 *** | 0.252 *** | 0.259 *** | 0.253 *** | 0.441 *** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhi, K.; Tan, Q.; Chen, S.; Chen, Y.; Wu, X.; Xue, C.; Song, A. How Does Social Security Fairness Predict Trust in Government? The Serial Mediation Effects of Social Security Satisfaction and Life Satisfaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6867. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph19116867

Zhi K, Tan Q, Chen S, Chen Y, Wu X, Xue C, Song A. How Does Social Security Fairness Predict Trust in Government? The Serial Mediation Effects of Social Security Satisfaction and Life Satisfaction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(11):6867. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph19116867

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhi, Kuiyun, Qiurong Tan, Si Chen, Yongjin Chen, Xiaoqin Wu, Chenkai Xue, and Anbang Song. 2022. "How Does Social Security Fairness Predict Trust in Government? The Serial Mediation Effects of Social Security Satisfaction and Life Satisfaction" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 11: 6867. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph19116867