Preserving Authenticity in Urban Regeneration: A Framework for the New Definition from the Perspective of Multi-Subject Stakeholders—A Case Study of Nantou in Shenzhen, China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Formation and Development of Urban Villages in Shenzhen

1.2. Debates on the Regeneration: Demolish or Preservation?

1.3. The Evolution of Urban Authenticity: From Object- to Multi-Subject-Centered Definition

2. Materials and Methods

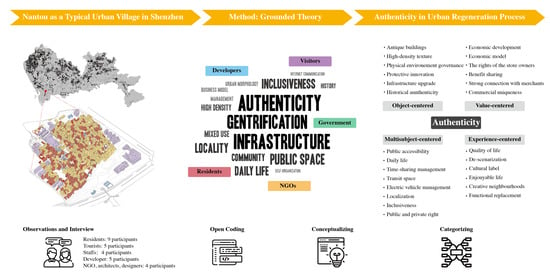

2.1. Grounded Theory (GT)

2.2. Study Site: Nantou

2.3. Research Participants

2.4. Data Collection: Observations and Interviews

2.5. Data Analysis

2.5.1. Open Coding

2.5.2. Identifying the Concepts

2.5.3. Generating the Categories and Subcategories

2.5.4. Discovery of the Core Category of “Authenticity” and Generating the Theory

3. Results

3.1. Concepts Related to the Effectiveness of Urban Regeneration

3.2. Conceptual Framework of Authenticity

3.2.1. The ‘Object-Centered’ Authenticity

“The environment before the renovation was quite poor. We took it over and basically transformed it in a protective way, which is equivalent to demolishing two buildings without moving the principle and the outline, combining them into one building, which has primarily the same outline but with a brand-new pattern” (transcript of the interview with an architect).

“Before the renewal, Nantou was just a normal urban village, with all the advantages and disadvantages of Shenzhen’s urban village. I do not think its history is true, to be honest. I think Shenzhen has no respect for history. If this place is properly protected, its authenticity will not be so false” (transcript of the interview with one of the Vanke developers).

3.2.2. The ’Value-Centered’ Authenticity

3.2.3. The ‘Experience-Based’ Authenticity

“I’m actually more concerned about the brand of Nantong Old Town, saying that the brand might be a little bit bigger, or what is our brand content? Of course, we may have a brand positioning, and then we have some research on the brand, but how the outside world perceives this is very important. For example, if we say we are a benchmark project for a more free, fresh, organic, and sustainable culture, then the clientele is most important for a project. If the clientele is not right, it means that the tenants may not fit in with our activities” (transcript of the interview with one of the Vanke developers in the Planning Department).

3.2.4. The ‘Multi-Subject-Centered’ Authenticity

“It has a very large number of indigenous people, which is what we find attractive because it is not an empty art or cultural park. It has a localized thing. It even has its own community of old Nantou, WeChat group, and tenant’s group. It has a very dense local network, this is its great advantage. But it is true that in 2020, there were some communication conflicts in the middle because of the renewal, and the indigenous people have very strong opinions about the renovation. For example, we hope that some entrance space is given to the public space, which involves more precise property boundary demarcation. Most of the conflicts were handled quite cleverly, for example, through some other compensations, so that the balance between public and private owners could have a better final handshake” (transcript of the interview with a leader of an NGO).

3.3. Differences in Perceived Authenticity between Stakeholders

3.3.1. Object-Centered Historical Authenticity in the Perspective of Tourists

3.3.2. Value-Centered Authenticity/Locality in the Perspective of Developer and Designers

3.3.3. Multi-Subject-Centered Authenticity in the Perspective of Residents and NGOs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harvey, D. “The Right to the City”: From International Journal of Urban and Regional Research (2003). In The Urban Sociology Reader; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-1-13-624415-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hansell, N. The Effect of the Man-Made Environment on Health and Behavior. Am. J. Psychiatry 1977, 134, 1321–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistical Bulletin of the People’s Republic of China on National Economic and Social Development in 2021. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/202202/t20220227_1827960.html (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Wu, W. Migrant Housing in Urban China: Choices and Constraints. Urban Aff. Rev. 2002, 38, 90–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, P.; Sliuzas, R.; Geertman, S. The Development and Redevelopment of Urban Villages in Shenzhen. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zenou, Y. Urban Villages and Housing Values in China. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2012, 42, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendlebury, J.; Short, M.; While, A. Urban World Heritage Sites and the Problem of Authenticity. Cities 2009, 26, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandarin, F.; van Oers, R. The Historic Urban Landscape; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zukin, S.; Trujillo, V.; Frase, P.; Jackson, D.; Recuber, T.; Walker, A. New Retail Capital and Neighborhood Change: Boutiques and Gentrification in New York City. City Community 2009, 8, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottie-Sherman, Y.; Hiebert, D. Authenticity with a Bang: Exploring Suburban Culture and Migration through the New Phenomenon of the Richmond Night Market. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 538–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttormsen, T.S.; Fageraas, K. The Social Production of ‘Attractive Authenticity’ at the World Heritage Site of Røros, Norway. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2011, 17, 442–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, S.X.B.; Tian, J.P. Self-Help in Housing and Chengzhongcun in China’s Urbanization. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2003, 27, 912–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenzhen Urban Planning Bureau. Masterplan of Urban Regeneration in Shenzhen. Available online: http://pnr.sz.gov.cn/attachment/0/394/394755/5842065.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- González Martínez, P. Urban Authenticity at Stake: A New Framework for Its Definition from the Perspective of Heritage at the Shanghai Music Valley. Cities 2017, 70, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 1964; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. The Nara Document on Authenticity. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/uploads/events/documents/event-833-3.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Zukin, S. Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-0-20-379320-6. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Kang, J. A Grounded Theory Approach to the Subjective Understanding of Urban Soundscape in Sheffield. Cities 2016, 50, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, H.J.; Son, Y.H.; Kim, S.; Lee, D.K. Healing Experiences of Middle-Aged Women through an Urban Forest Therapy Program. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 38, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheider, S.; Kuhn, W. Affordance-Based Categorization of Road Network Data Using a Grounded Theory of Channel Networks. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2010, 24, 1249–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenzhen Bureau of Statistics Shenzhen Statistical Yearbook 2021. Available online: http://tjj.sz.gov.cn/nj2021/nianjian.html?2021 (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Hao, P.; Geertman, S.; Hooimeijer, P.; Sliuzas, R. Spatial Analyses of the Urban Village Development Process in Shenzhen, China. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2013, 37, 2177–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D. The End of Public Space? People’s Park, Definitions of the Public, and Democracy. In Common Ground?: Readings and Reflections on Public Space; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; pp. 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Martínez, P. Authenticity as a Challenge in the Transformation of Beijing’s Urban Heritage: The Commercial Gentrification of the Guozijian Historic Area. Cities 2016, 59, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zamanifard, H.; Alizadeh, T.; Bosman, C. Towards a Framework of Public Space Governance. Cities 2018, 78, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carmona, M. The Place-Shaping Continuum: A Theory of Urban Design Process. J. Urban Des. 2014, 19, 2–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participants | Number of Participants | Word Courts of Transcripts | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 Introduction | Q2 Responsibility | Q3 Corporation | Q4 Concern | Q5 Before & After | Q6 Effectiveness | Q7 Future | Total | ||

| Inhabitants | 9 | - | - | - | 1982 | 753 | 1683 | 453 | 4871 |

| Commuters | 5 | - | 473 | - | 447 | 586 | 822 | 510 | 2838 |

| Tourists | 4 | - | - | - | 183 | 153 | 384 | 683 | 1403 |

| Developers | 5 | 1945 | 3254 | 7854 | 10,307 | 2158 | 4244 | 4779 | 34,541 |

| NGO | 4 | 1437 | 3923 | 3001 | 11,061 | 2315 | 11,894 | 2875 | 36,506 |

| Total | 27 | 3382 | 7650 | 10,855 | 23,980 | 5965 | 19,027 | 9300 | 80,159 |

| Memos | Open Coding | Conceptualizing Data | Categorizing Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| “History: capital of eastern Guangdong, source of Guangdong and Hong Kong.” “I hope Nantou will become a pluralistic community with” “Make tenants and residents aware of the benefits of urban renewal” “The biggest problem is the small block texture of the village within the city” “Multiple experiences for visitors” “The regenerated Nantou is more diversified” “Diversified business types, diversified customer groups, and diversified architectural forms” “Community and street culture” “Space inclusive, pet-friendly, elderly, children, and other people friendly” “Upgrading of business mode due to the investment in transformation and cultural industrial zone planning” “We are in the process of investment, the first one to avoid it a scenic, no matter the format or brand above “I think both the strength and problem of Nantou is a large amount of aboriginal status, and that’s what we find very attractive about it” …… | v1 history of Nantou …… v3 diversity of the community v4 Benefits for all v5 the urban texture …… v10 diversity in experiments v11 diversity in visitors v4, v5 …… v22 keep the street culture v23 inclusiveness …… v46 investment and the profit model …… r23 Avoid commercialization …… n7 Show local characteristics | C1 history (v1, v2, v7, v49, d9, d8, r26, r29) C2 mixed-use (v3, v11, d14, d2) C3 urban morphology (v21, d4, n20, r9) C4 infrastructure (v6, v8, v19, v55, n22, r3, r5, r11) C5 business model (d17, v46) C6 high density (v5, r12) C7 inclusiveness (v10, v23, v28, d10, v4, v53, r14) C8 locality (v36, d1, d3, d12, d11, n7, n6) C9 gentrification (v54, d5, d7, n18, r16, r17, r18, r21, r23, r24) C10 daily life (v22, v47, n11, d6) C11 community (n8, n14, d15) C12 management (r2, r7, v17) C13 public space (v20, n9, d13, d16) C14 Self-organization (v30, v51, n23) C15 Internet Communication (r30, d7) | CC1 Physical environment CC1c1 urban morphology CC1c2 infrastructure CC1c3 high density CC2 Social equality CC2c1 public space CC2c2 inclusiveness CC2c3 business model CC2c4 gentrification CC3 Culture Authenticity CC3c1 locality CC3c2 history CC3c3 ordinariness |

| 134 items | 15 items | 3 categories & 10 subcategories |

| Categories | Subcategories | Related Concepts (Term Frequency) |

|---|---|---|

| Improvement of Physical Environment | Urban morphology | High-density texture (6), residential buildings with characteristics of different periods (3), public squares (3), main streets (15), back streets (10), Mixed-use (4) |

| Infrastructure | Electricity supply system (3), drainage system (5), parking (2), gas pipe (1) | |

| Governance | Security (3), clean-keeping (3), emergency handling (2), pandemic control (1), electric vehicle management (3) | |

| Establishment of Social Equality | Publicness | Public events (7), public life (4), public accessibility (7), balancing public and private property rights (4) |

| Inclusiveness | Children friendly (1), pet friendly (1), benefits for all (4), co-living (5), vitality (7), demands of the store owners (5), benefits for the original inhabitants (11) | |

| Business model | Marketing (9), area efficiency (2), rent (5), business environment (5), branding (4) | |

| Gentrification | Replacement of inhabitants (10), function replacement (5), rising rents, consumption upgrading (8), taste for young people (7) | |

| Preservation of Cultural Authenticity | Locality | Local brand (7), local design (6), local food (7), localization (7), bottom-up process (7), Self-organization (3), self-construction (4) |

| History | History of Nantou (8), Traditional architecture (3), protective renovation (7), history authenticity (5), fake façade (3), cultural label (3) | |

| Ordinariness | daily life (4), vegetable market (2), space for strolling (6), community (3) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, S.; Qu, F. Preserving Authenticity in Urban Regeneration: A Framework for the New Definition from the Perspective of Multi-Subject Stakeholders—A Case Study of Nantou in Shenzhen, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9135. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph19159135

Li S, Qu F. Preserving Authenticity in Urban Regeneration: A Framework for the New Definition from the Perspective of Multi-Subject Stakeholders—A Case Study of Nantou in Shenzhen, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(15):9135. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph19159135

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Shuyang, and Fei Qu. 2022. "Preserving Authenticity in Urban Regeneration: A Framework for the New Definition from the Perspective of Multi-Subject Stakeholders—A Case Study of Nantou in Shenzhen, China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 15: 9135. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph19159135