1. Introduction

The European Landscape Convention (ELC) has linked the values of landscape to people’s identity and perception [

1,

2,

3]. The innovative approach to landscape design is based on the interaction between protection and valorisation of the whole territory and landscape resources, following the principles of active conservation. The ELC has been ratified in 38 European countries, but its applications have been heterogeneous, according to alternatively different geographical areas, administrative levels and planning systems [

4,

5,

6]. Landscape becomes the centre of territorial governance as an opportunity for local development in a perspective of sustainability and resilience, with the use of multilevel landscape plans, from regional to local and sectorial dimensions [

7,

8,

9].

In Italy there is a long legislative tradition in the field of landscape and cultural heritage protection. During the fascist period, two important acts, known as Bottai laws, were introduced in 1939: Law n. 1089, which protects works of art and other aesthetically significant tangible assets, and Law n. 1497, which introduces a first landscape regulation for areas of particular environmental, natural and scenic value. Since 1948, the article 9 of the Italian Constitution has protected the landscape and the historical and artistic heritage of the Nation. Later, the Galasso Law (Law n. 431 of 1985) established a protection constraint on the national territory with particular natural characteristics, and provided for the drafting of landscape plans for the management of areas already protected by Law n. 1497 of 1939. The several legislative acts are now included in the Code of Cultural Heritage and Landscape (Law n.42 of 2004, known as Urbani Code). Following the terms of the ELC, it identifies the landscape as “the territory expressing identity, whose character derives from the action of natural and human factors and their interrelationships” (article n. 131), linked to the history and expression of the culture of the communities. In the international context, the concept of landscape is strongly integrated with the environmental component, while in Italy the framework of laws and regulations emphasizes the cultural dimension [

10,

11]. The Italian territory is characterized by a long history that has resulted in a continuous stratification of alterations and human interventions on the environment, thus giving a strong cultural character to the landscape, in which also the natural components of high ecological value are the outcome of the anthropization process [

12].

Each landscape is distinguished by a complex combination of human and natural factors, including intangible values, which constitutes the identity of place, a sense of belonging, continuity and authenticity, the so-called “genius loci” [

13,

14,

15]. The system of tools for landscape protection and enhancement is strengthened by the important role of the RLP in the territorial governance. It should define the charter of the territory according to a multidisciplinary approach and not only according to a multidisciplinary approach, and establish the modalities of conservation, use and transformation of the territorial assets. The principles set out by this legislation open a season of renewal in the field of territorial planning, in an attempt to improve the analytical and interpretative systems of territorial values [

16].

Landscape planning should guarantee the coherence of territorial government choices with the objectives of landscape quality and sustainable development. The landscape plan is not limited to propose the technique of the constraint, aimed exclusively at the preservation of the territorial invariants, but carries out programmatic and planning objectives traditionally attributed to the competence of local administrations. The landscape plan can identify guidelines for projects of conservation, recovery, redevelopment, valorisation and management of regional contexts, indicating the appropriate tools, including incentives, to realise them. The definition of prescriptions for the landscape protection and the identification of sustainable development strategies represent the basic objectives of the RLP, as required by national legislation.

The action of landscape planning should not only concern the imposition of restrictions, interpreted as legislative constraints, which are subject to public control due to the recognition of territorial and landscape values. However, it should rather aim at the promotion of development opportunities and new economies that are compatible with the territorial resources [

17].

The landscape plan is superordinate with respect to local planning and, therefore, from the date of approval, its regulations and prescriptions are immediately binding and prevail over the provisions of territorial and urban plans. Today landscape represents an important issue in the project of territory. However, in Italy, several criticalities still need to be resolved about the difficult transition from the scenarios of valorisation identified by the strategic contents of the plans into the normative recommendations for the project, often limited to the conditions for the intervention’s compatibility [

8].

The Code provides for a collaboration essentially limited to two public authorities, the Ministry and the regions, in the definition of guidelines and criteria concerning the activities of protection, valorisation, planning and management of the interventions. The joint drafting of RLPs between the national government and the regions can be carried out through the signing of special agreements, which also establish terms and conditions for the final drafting of the plan. They ensure that the whole territory is adequately known, protected, planned, and managed because of the different values expressed by the specific contexts, defining areas with homogeneous landscape characteristics and peculiar aspects and establishing regulations based on specific quality objectives. From a legislative point of view, the role of local authorities, particularly of municipalities, could appear secondary in landscape policies.

In truth, the achievement of the RLP objectives requires the adaptation of local planning tools. In some cases, this process allows to simplify the procedures of landscape authorization for interventions concerning highly compromised or degraded areas, identified by the plan, or protected areas, not affected by specific declaration of public interest.

The ineffectiveness of landscape policies is often due to the lack of participation of local authorities and communities in the landscape vision and planning approaches developed at the regional level.

The RLP identifies the territorial components to be subjected to measures of conservation and valorisation, involving a cooperation between the Ministry and the region for landscape assets of relevant public interest (Law no. 1497 of 1939), areas protected by law (Law no. 431 of 1985) and further properties and areas specifically identified and subject to protection by landscape plans. This approach is expressed in different ways by regional landscape plans and by the specific implementation of guidelines and prescriptions by municipal planning, not always according to the needs and demands expressed by local communities.

The framework of the landscape planning in the different Italian regions highlights a widespread delay in the drafting and approval process, as shown in the overview made available by the Ministry (December 2020). In 2004, most Italian regions already had a regional landscape plan covering the whole territory or a well-defined part of it, except for Calabria and Friuli Venezia Giulia [

18].

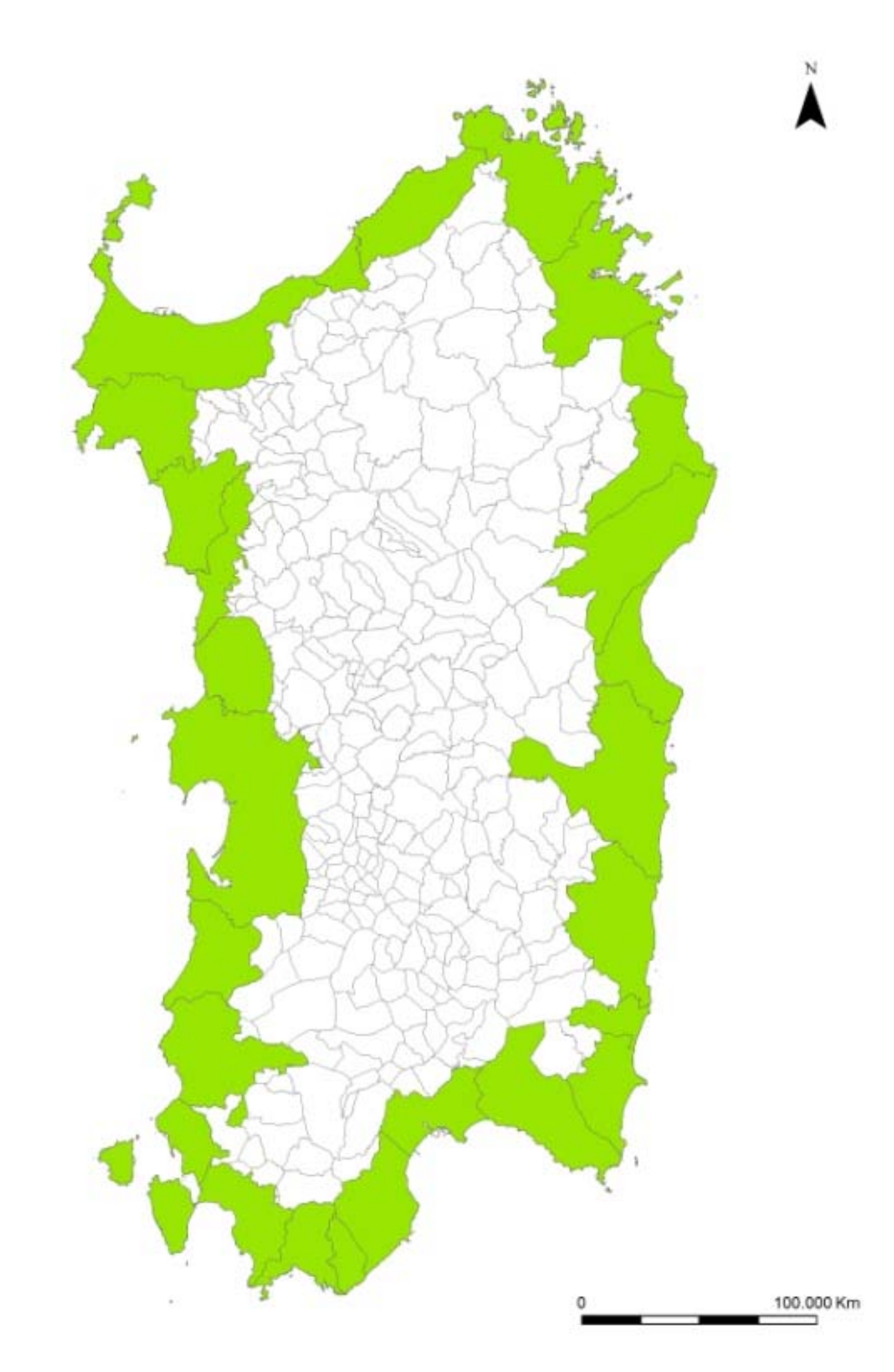

Today, the number of RLPs or Regional Territorial Plans (RTP) with landscape value or Regional Territorial Landscape Plans (RTLP), that have been approved in compliance with the Urbani Code, is still limited (

Figure 1): the RLP of Sardinia, approved in 2006 and limited to coastal areas; the RTLP of Apulia and the RTP with landscape value of Tuscany, both approved in 2015; the RLP of Piedmont in 2017 and the RLP of Friuli Venezia Giulia in 2018.

Regional authorities take sometimes decisions unilaterally. For example, the RLP of Lombardy has been approved in 2010 without co-planning with the Ministry of Culture (MiC). In the case of the Regional Landscape Territorial Plan (RLTP) of Lazio, approved in 2019 by the region without taking into account the previous work and decisions shared at the joint technical table with the Ministry, the Council of Ministers has appealed to the Constitutional Court against the region for conflict of attribution, leading to the cancellation of the approval of the RLTP in October 2020 [

18].

Additionally in Veneto, the process of joint elaboration of an RTP with landscape value has shown the inter-institutional conflict between the region and the Ministry. After the agreement of 2009, in the same year, a partial amendment of the RTP was adopted to attribute the landscape value. Finally, the region has approved a plan without landscape value in 2020 and today it is discussing with the Ministry for the updating of the agreement on the joint drafting of a new RLP.

Some regions have a certain autonomy in landscape matters, which allows them also to avoid the mandatory cooperation with the Ministry (Valle d’Aosta, Trentino Alto Adige, Sicilia). Valle d’Aosta has a Landscape Territorial Plan on a regional scale before the approval of the Urbani Code. Friuli Venezia Giulia has defined landscape planning tools on different levels, from the provincial dimension for the Province of Trento to the municipal scale for the Province of Bolzano [

19]. The Sicilia region has approved provincial landscape plans, in compliance with the Urbani Code.

The other regions (Liguria, Emilia Romagna, Umbria, Marche, Abruzzo, Molise, Basilicata, and Calabria) have signed an agreement with the MiC for the joint drafting of the plan, which is still in progress. The Campania region has to finalize the preliminary RLP, adopted in 2019.

The paper focuses on the case study of the Regional Landscape Plan of Sardinia, the first of the season started by the Urbani Code and an example of the few plans not extended to the whole regional territory. The extension limited to a certain area is still the main weakness of the RLP, in addition to the still ongoing municipal planning update. The plan is strictly oriented towards the protection of landscape from the settlement pressure on the coast, which was considered more sensitive by the regional political decision-maker, who had to intervene urgently after the failure of the previous territorial landscape plans [

20].

The research reflects on the topic of the inter-institutional collaboration between the Ministry, region, and local authorities, focusing on the ways of transferring the guidelines and strategies of the RLP into the municipal urban planning, with special attention to the general level. The main research goal is to evaluate the level of implementation of the process of adaptation of municipal planning to the RLP in Sardinia in order to reflect on the effectiveness of the landscape plan in the transfer of planning guidelines to the local scale, between conservative measures and development scenarios.

2. Materials and Methods

The paper investigates the effectiveness of the RLP of Sardinia in the application of guidelines and regulations at the local level, through the process of adaptation of municipal urban planning. The research has been structured in different phases:

- −

A study of the Sardinian landscape plan and an analysis on the state of the process of adaptation of municipal urban plans to the RLP;

- −

A qualitative comparative analysis of the municipal urban plans that have been already complied to the RLP;

- −

A survey of the coherence verifications elaborated by the Sardinian Region for the plans in course of updating.

The elaboration of an updated overview of the municipal urban plans adapted to the RLP has allowed some preliminary reflections on the effects of the application of the transitory rules of the landscape instrument, from 2006 to date, with consequent limitations to the socio-economic development of the territory.

In the second step of the research, 28 municipal urban plans already adapted to the RLP have been analysed, using a qualitative comparative method to assess the level of integration of landscape contents in local urban planning [

21,

22]. In this analysis, the main documents of the plan have been examined, in particular, the regulations and the illustrative reports, collected from the institutional websites of each municipality.

The framework of the comparative analysis, outlined in

Table 1, has been based on the RLP regulations, which establish the contents of the municipal urban plans to be developed in the adaptation process, according to article 107.

The issues of investigation are related to the four main goals of the RLP: recognition of landscape values, landscape protection, landscape valorisation, and compatible transformation. Each of the ten points identified, which represent the essential contents to give a landscape character to the municipal plan, has been evaluated according to the presence and relevance of the specific issue in the plan documents.

The assigned scores have been graded on three levels:

- −

0 points if the content is completely missing or not relevant;

- −

0.5 points if the content is not significantly addressed in the plan;

- −

1 point if the content or the approach is coherent and relevant in the plan.

The overall sum of the scores provides an evaluation for each municipal plan of the degree of integration of the landscape contents.

Scores have been assigned according to the following criteria:

- −

Up to 2.5 points—low;

- −

3 to 5 points—medium;

- −

5.5 to 7.5 points—high;

- −

8 to 10 points—very high.

Another outcome concerns the qualitative evaluation of the relevance of each landscape content in the selected local urban planning tool, thus assessed:

- −

Up to 7 points—low;

- −

7.5 to 14 points—medium;

- −

14.5 to 21 points—high;

- −

21.5 to 28 points—very high.

In the second part of the research, an analysis of a representative sample of coherence checks has been carried out. The coherence check is a procedure required by the Sardinian regional planning law, which involves the verification of the compliance of the approved municipal urban plan with the superordinate instruments. A positive decision is an essential condition for the entry into force of the plan. The regional authority provides specific recommendations on the contents and requests integration or corrections.

Documents published on the website of the region of Sardinia, relating to 34 procedures of municipal urban plan drafting, ongoing or completed, have been collected. The analysis of the remarks of the regional authority has allowed creating a list of common criticalities, then classified in thematic groups and assessed in terms of frequency. The description of the results has been structured by themes and can be used to identify, according to a deductive approach, the frequent critical points that are delaying or discouraging the finalisation of the process of adjustment of the plan.

3. The Regional Landscape Plan of Sardinia

In 2006, the Region of Sardinia has approved the first landscape plan in accordance with the Urbani Code, anticipated by the introduction of some temporary rules for the protection of the coastline, the so-called Save Coasts Law, RL n. 8 of 25 November 2004, entitled “Urgent rules of temporary protection for landscape planning and preservation of the regional territory” [

23]. The legislative act expected the approval of the RLP within one year and imposed the prohibition of building developments in the coastal territories included in a belt of two kilometres from the shoreline. It aimed to avoid a loss of coastal resources during the critical period of vacancy prior to the adoption of the new RLP. For more than a decade, the Sardinian RLP targeted the territorial government towards the preservation of the landscape and the promotion of sustainable development through the control of urban sprawl, the mitigation of settlement pressure, the recovery of compromised and degraded landscapes and the soil protection [

24]. The directives and prescriptions of the RLP are based on the principle of control of territorial phenomena characterized by widespread urbanization, landscape destruction, soil consumption and progressive reduction of natural resources.

The plan has focused on the coastal strip, a landscape asset of high environmental value, affected by strong anthropic pressure. Therefore, it does not allow the transformation of uncompromised areas, except for the completion of existing settlements. It also proposes actions of architectural recovery, landscape and environmental redevelopment, reuse of existing buildings for the tourist accommodation with delocalization from the coastal strip of non-residential and tourist uses, if not functionally connected to the sea. Tourist attractiveness must be supported through efficient use of the existing urbanized areas (main urban centres, sprawl agglomerations and dismissed productive sites) or, if necessary, by new developments in continuity or integration to the existing urban fabric. Municipal plans should integrate the prescriptions of the RLP and put in place actions of redevelopment and completion of existing settlements according to criteria of land take reduction, preservation of the historical or consolidated urban patterns and transformation of incoherent settlement forms [

25].

The project of the new settlements, based on a detailed assessment of the social demand over ten years, must be inspired by compact residential models according to criteria of connection and structural integration with the existing settlement.

The knowledge framework, structured according to three main components (environmental, cultural historical and settlement), includes several disciplines that contribute to define the “charter of the territory”. Landscape is considered as a complex system of heterogeneous components, complementary and interdependent, in a state of constant transformation, but in a perspective of a progressive balance. The landscape project must therefore interpret the relationships between the different elements, which constitute scenarios that are in turn interrelated to create systems of local identity.

However, the plan analytical framework and the strategic vision are limited to the coastal zone, which includes about 41% of the regional territory. It also explores the concept of “landscape area”, already introduced in the Urbani Code, which identifies portions of territory characterized by landscape homogeneity and subject to specific regulations (

Figure 2). The 27 landscape coastal areas are intended in a perspective of active conservation of landscape and environmental components. Local authorities are required to identify, within the general plan, the “local landscape areas”, characterized by common elements and subject to the characteristics of “immateriality” arising from the sense of belonging of communities to places [

26].

The plan aims to preserve, valorise and hand down to future generations the environmental, historical, cultural and settlement identity of the territory.

In order to achieve the main goal of preserving, protecting, valorising and transferring to future generations the environmental, historical, cultural and settlement identity of the territory, the RLP establishes the criteria for the identification of the landscape values to be protected, without submitting them to an adequate activity of public participation, strongly reduced due to the time constraints for the plan drafting [

27]. The first phase of institutional consultation (2006) involved a cycle of public conferences or co-planning, further developed through meetings with local authorities, municipal and provincial technical offices and the heads of the Regional Plan Office aimed at improving the final draft of the ongoing RLP. In January and February 2006, a total of 24 meetings have been organized, of which 22 have been addressed to the municipalities of the interested areas, one to the provinces, and the last one to the associations of industry, commerce and craftsmanship. This is a critical issue, due to the lack of an adequate public participation activity.

The RLP contents have a descriptive, prescriptive and propositional character. They provide guidelines and prescriptions for the conservation and maintenance of the most relevant landscape features and define the actions and the territorial transformations in a perspective of sustainable development.

The provisions of the RLP are mandatory for local authorities and immediately prevail over any different and less restrictive provisions contained in the municipal plans and in other sectorial planning acts with spatial impact. In any case, the identified landscape and assets are subject to the RLP regulation, regardless of their location. The other provisions of the RLP are immediately effective for the municipalities totally or partially included in the coastal landscape areas (

Figure 3).

The RLP is designed to provide a framework of rules and to remove any kind of arbitrariness and excessive discretion both for the region and for local authorities. During the adaptation of the urban general plan, the municipalities have the possibility to extend the environmental, landscape and historical-cultural values, based on a detailed territorial knowledge, and to integrate the strategies for their enhancement.

The RLP provisions can be implemented with the adaptation of provincial, municipal and sectorial planning, also through agreements between the region, provinces and municipalities involved in the definition of strategic actions of urban recovery and territorial transformation, based on objectives of landscape quality.

The Sardinian RLP has adopted a temporary regulation that is particularly restrictive for the coastal landscape areas, until the adaptation of the municipal urban plans. In particular, for those costal municipalities without a municipal urban plan in line with the RLP, building activities are allowed only in the urbanised area and in the development areas close to that already urbanized and surrounded by geographic, infrastructural and settlement elements, if scheduled in executive plan in force at the date of the RLP adoption.

4. Results

4.1. The State of Progress in the Process of Adaptation of Municipal Urban Plans to the RLP

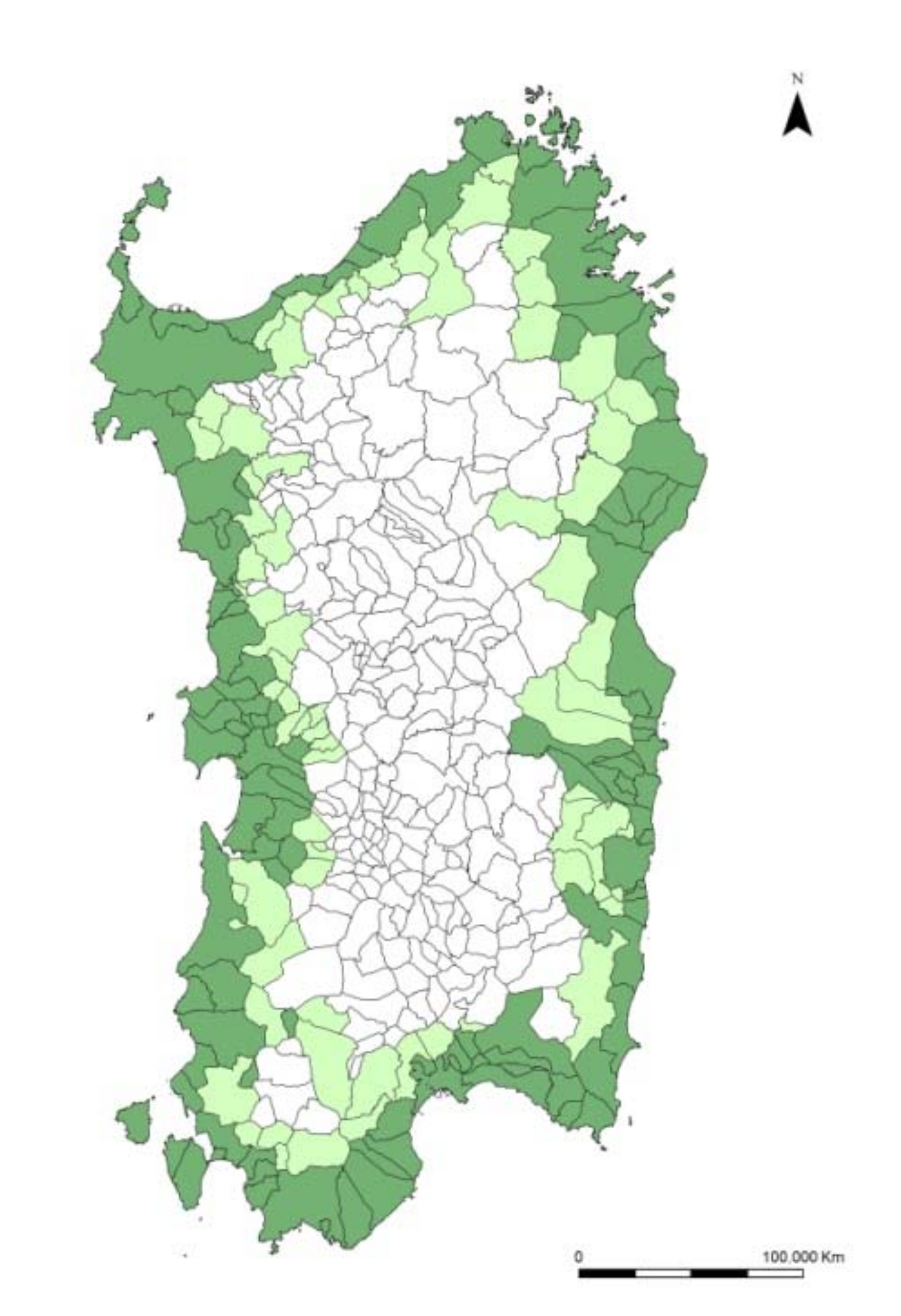

The effectiveness of the landscape plan, in achieving real effects and outcomes on the territory, is linked to the state of the process of adaptation of municipal urban planning to the RLP prescriptions and guidelines. The system of constraints, in force during the transitory period, strongly limits the territorial transformations in the municipalities that fall entirely within the coastal landscape (102 municipalities out of a total of 377), subject to the compulsory adaptation of the general plan, within one year from the entry into force of the RLP. Instead, it is voluntary for municipalities partially included (65 municipalities) or not included in coastal landscape areas (210 municipalities). To date, only 28 municipalities have completed the process of adapting the general plan. Only 22 of them are entirely in coastal areas, and thus effectively required to do so (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). In general, the urban planning framework in Sardinia still shows a significant number of municipalities with out-of-date instruments (General Regulatory Plans and Construction Plans), overtaken by the Regional Urban Law n.45/1989. The transitory rule that prohibits new urban developments, excluding those already approved, until the adaptation of municipal plans to the RLP, has strong economic effects due to a complete interruption of new urban projects, temporary but often for a long time.

More than 78% of municipalities have not respected the timeframe set by law for the adaptation. The average time between the date of first adoption of the plan and the approval, as shown in

Table 2, is approximately four years, ranging from one to over eight years. This is partially due to the absence of sanctions or penalties for non-compliant administrations but also to a lack of political will by local authorities to accept the guidelines of the RLP, which are often not appreciated by communities.

4.2. The Qualitative Comparation of Urban Municipal Plans Compliant with the RLP

The comparative analysis of the municipal plans in compliance with RLP, summarised in

Table 3, has underlined a medium/low integration of the landscape contents in the local urban instruments, which often consist in detailed analytical frameworks, not associated with an effective normative, project and strategic component.

Almost all plans contain the detailed recognition of the cultural, historical, environmental and landscape heritage (A1), which are already identified for the most part in the RLP documents and deepened at the local scale. In the same way, the regulations of municipal plans define the regime of protection which, in the case of historical-cultural and landscape assets, are defined during co-planning with the Ministry (B1).

The signing of the co-planning agreement for the protection of the historical and cultural heritage is a necessary condition for the conclusion of the approval process of the plan. Most of the plans define measures and actions for building rehabilitation (D3), for example maintenance of morphologies and traditional characters related to local architectural types, techniques and construction materials. They often look like guidelines and indications whose real effectiveness is not ensured if not supported by measures to discourage the consumption of natural soil. It is a weak point of municipal urban planning.

The transformations expected by the plan are not usually based on the principle of minimum land consumption (D1) or evaluated according to the recognized landscape values (D2). Even if the plan states and underlines this principle, according to the RLP guidelines, in practice it often adopts expedients and methodologies for assessing the demand and supply of developable areas that lead to overexploitation, especially in contexts with a strong real estate market.

A further important point is represented by the identification of the local landscape areas, which constitute the interpretation of the characters of local identity and landscape peculiarities (A2), in most cases identified but supported by weak project strategies for the environmental and landscape valorisation (C1). Landscape is analysed in terms of recognition of the system of values to be protected, but very rarely risks and vulnerability factors have been identified (B2), as well as the conditions to define a model of sustainable local development (C2). Some plans establish actions to mitigate and balance the negative impacts of urban transformations, with strategies to increase urban environmental quality, strengthen green and blue infrastructures, and define ecological systems and networks in the territory (D2).

In general, the plans in compliance with RLP often include landscape contents that are not adequately developed. They still adopt a strictly regulatory and traditional approach that does not fully reflect the philosophy of the ELC.

4.3. The Analysis of the Coherence Verifications of Urban General Plans

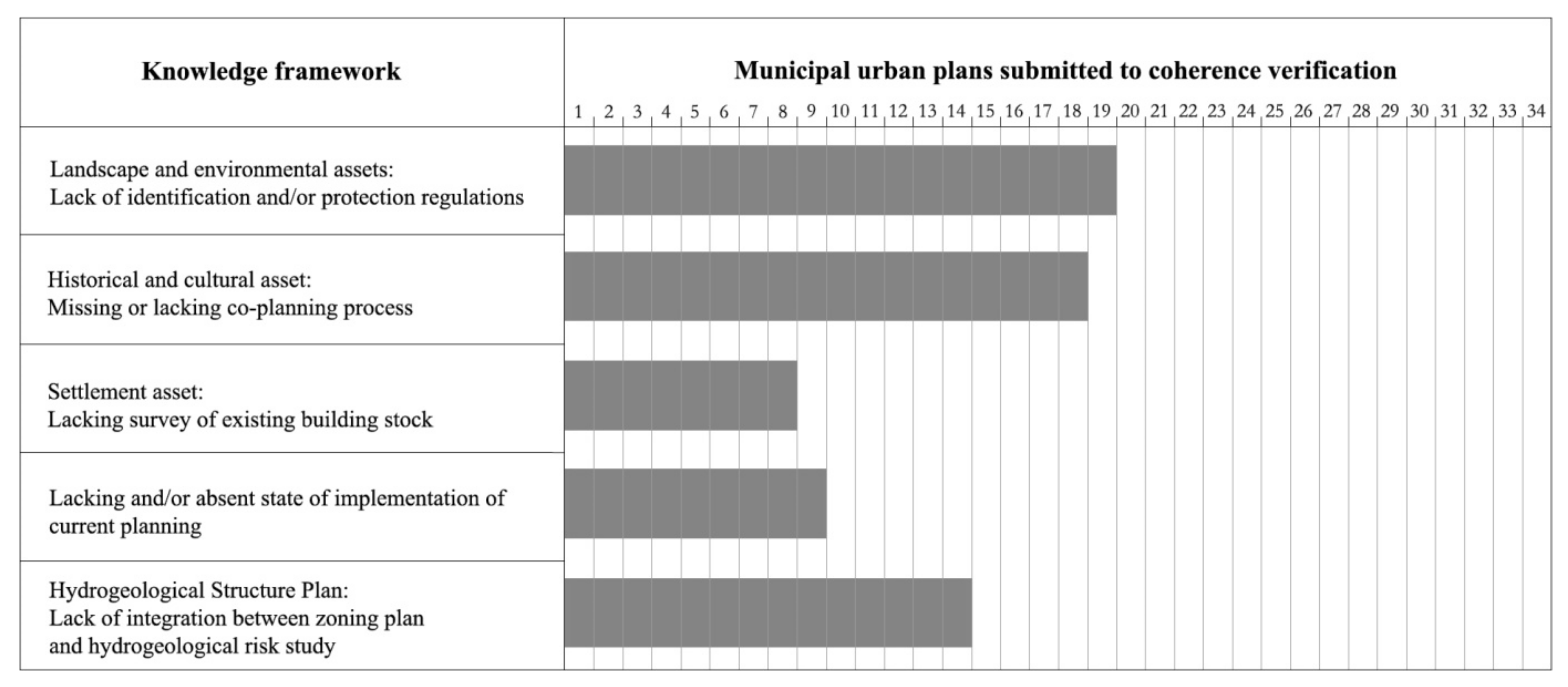

4.3.1. The Elaboration of the Knowledge Framework

In the process of adaptation of local plans to the RLP, municipalities should accurately deepen the contents of the superordinate plan according to the three basic assets: environmental, historical-cultural, and settlement. This task of knowledge reorganization aims to collect exhaustive territorial data, to support planning choices at the municipal level, and to verify the analyses elaborated on a regional scale, with a more detailed knowledge framework to guarantee a correct implementation of the landscape strategies. In February 2007, the Sardinia Region has published a first draft of guidelines for the adaptation of the municipal urban plans with the RLP and the Hydrogeological Structure Plan. The environmental asset refers to the natural resources and ecological values that represent peculiarities and connotative characters of the identity of places. It also analyses the interactions between the natural and the anthropic landscape. This issue should be expressed, within the urban municipal plan, in the recognition of landscapes at local level, through a reading of the territorial invariants, the collective perception and the opportunities for compatible and sustainable uses.

The recognition of the historical and cultural values has a relevant role in the procedure of adaptation of municipal plans to the RLP. In particular, it is necessary to survey and catalogue the archaeological and architectural heritage and the cultural and identity values to define a detailed regulation for the protection and valorisation [

27].

The study of the settlement structure requires an interpretation of the processes that have determined the current state of the built-up areas, analysing morphological, functional, socio-economic and cultural factors. In addition, it is necessary to carry out a detailed survey of the existing building stock, with the quantification of the legitimate and/or irregular volumes.

Another important knowledge topic concerns the hydrogeological territorial structure and the areas subject to hydraulic and landslide hazard must be verified at the municipal level and, if necessary, redefined, together with the proposal of some measures for risk mitigation. The analysis of the coherence checks has highlighted several problems related to the task of knowledge reorganization and to the level of deepening of the different issues concerning the landscape structure of the territory, in the downscaling from the regional to the municipal scale (

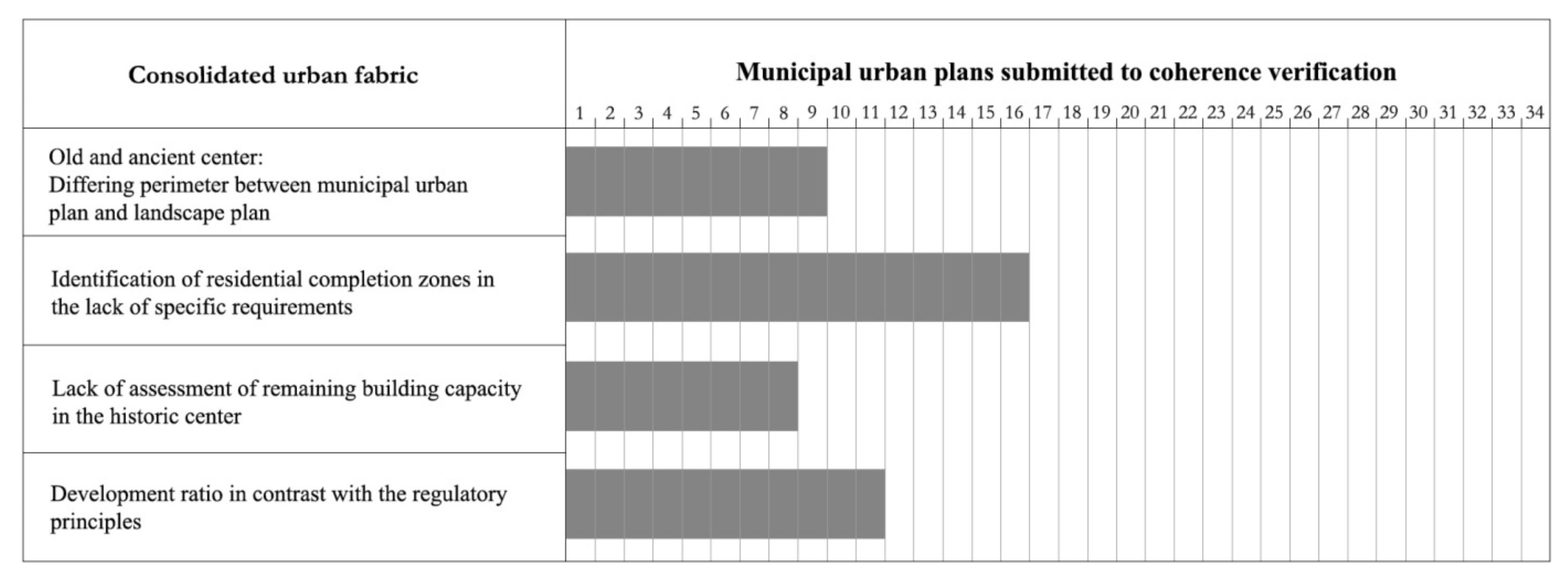

Figure 6).

Often there are deficiencies in the detailed recognition of the local landscape areas and the definition of the relevant guideline projects. In particular, the coherence checks have pointed out, in more than half of the analysed cases, the lack or incomplete identification of the environmental values and the landscape components and heritage, in addition to a lack of protection regulation.

Even the historical and cultural structure is not always adequately analysed and there are still criticalities in the listing and the definition of the rules for the protection and enhancement of the historical and cultural heritage, recorded in the database of the region of Sardinia.

A large part of the analysed coherence checks detect the failure to conclude the co-planning procedure for the historical-cultural asset, with the signing of an agreement between the Municipality, the region and the Ministry. Further difficulties are related to the definition of the settlement conditions and of the level of implementation of the provisions of the planning in force, in particular the assessment of the residual development capacity in the consolidated fabric and in the area of urban expansion partially implemented, in addition to the existing legitimate and/or irregular volumes. There is also frequently a lack of the hydraulic and geological compatibility study, or an overlap elaboration of the hazard areas identified with the zoning plan.

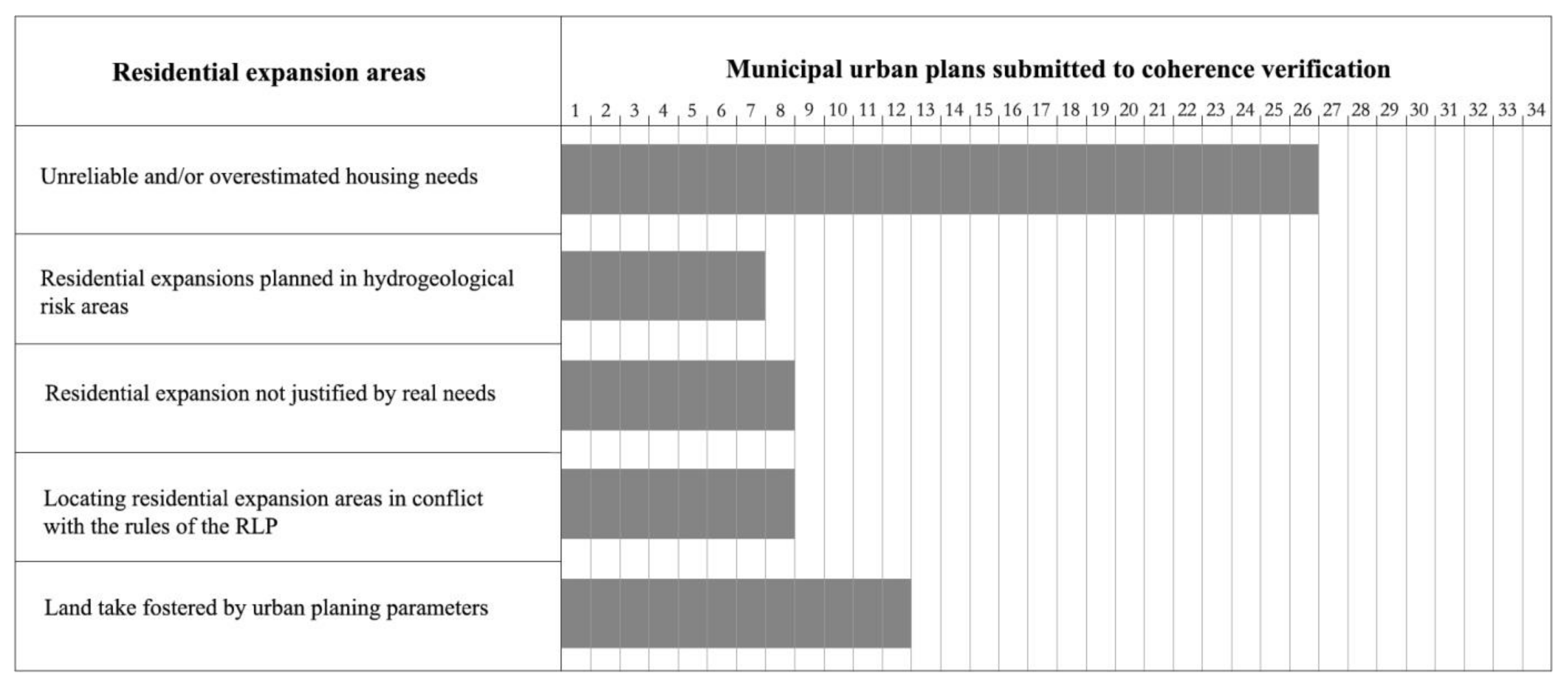

4.3.2. The Provisions for New Residential Building Developments

The sizing of the residential demand is usually not justified by an effective need, which is generated by a positive demographic trend due to birth rate or migratory phenomena, or by a previous demand, due to the presence of overcrowding or the reduction of the average size of families. The oversizing of the supply is pursued through the optimistic forecast of population growth or the incorrect future projection of statistical surveys to justify the need to expand the residential areas or to confirm a residual building capacity of the current plan. This is a common criticality in the coherence checks: 26 municipalities out of 34 analysed have oversized the plan requirements, with a consequent negative outcome of the procedure, in some cases worsen by the planning of new residential expansion areas that exceed the assessment result (

Figure 7).

An inadequate survey of the residual capacity for building development in the urbanized area and the absence of a detailed assessment of existing buildings in a state of decay or underutilization is indicative of a desire to meet residential needs, real or theoretical, through the almost exclusive use of new construction. Any possibility of partial redistribution of the families in the stock of existing housing or building recovery is not considered in the planning strategies.

Further critical issues concern the allocation of new residential development often in natural or agricultural land, in strong contrast with the rules of the RLP aimed at reducing land consumption. Sometimes the new settlements are localised in areas at hydro-geologic risk, to confirm long-standing expectations of the owners, which the local authority does not want to disregard. During the coherence check, there are many remarks concerning the criteria for the residential settlements planning and design. For example, it is not appropriate to apply zoning parameters that encourage land consumption by using low building ratios for the development of extensive residential patterns with one- or two-family building types.

4.3.3. The Historical Centres and the Consolidated Urban Fabric

The consolidated urban fabric includes the old and ancient centres that are delimited by the RLP according to the historical cartography and verified in the co-planning with the regional authorities.

In the municipal plans, the old and ancient centre could be included in A zones (historical centre) and B zones (residential completion). The historical centre could be reclassified in sub-zones A1, with relevant traces of the original urban and architectural structure or monumental buildings of high historical and artistic value, and sub-zone A2, represented by altered urban patterns, which have partially or totally lost the typological characteristics of the built-up area and the road structure and will therefore be subject to urban requalification interventions.

The most frequently highlighted point is the difference in judgment between the recognition of the characteristics that identify the old and ancient centre and the subsequent definition of the land use zoning (

Figure 8). In addition, effective planning regulations for the A zone are not always guaranteed and should be subject to executive planning.

Totally or partially built-up areas can be included in the B zones of residential completion, that generally coincide with the urban expansions that occurred until the 50s and usually interposed between the old centre and the recent expansions. In the case of the identification of new B zones, respect to the current plan, it is not always verified the compliance with the parameters required by the Assessorial Decree n.2266/U of 1983 (Floris Decree), which for partially built-up areas provides for the existence of a built-up quantity not less than 10–20% of the total volume that can be realized.

In addition, the identification of new B zones is not allowed by regional legislation, for municipal plans in compliance with the Floris Decree, except in cases it is a correction of previous incorrect classification. These critical points have been found in over 40% of the analysed coherence checks. Relevant weaknesses concern the respect of urban planning standards: for over 30% of the analysed cases it is inadequate, not achieving the minimum requirements of the regulations or not certifying their real existence.

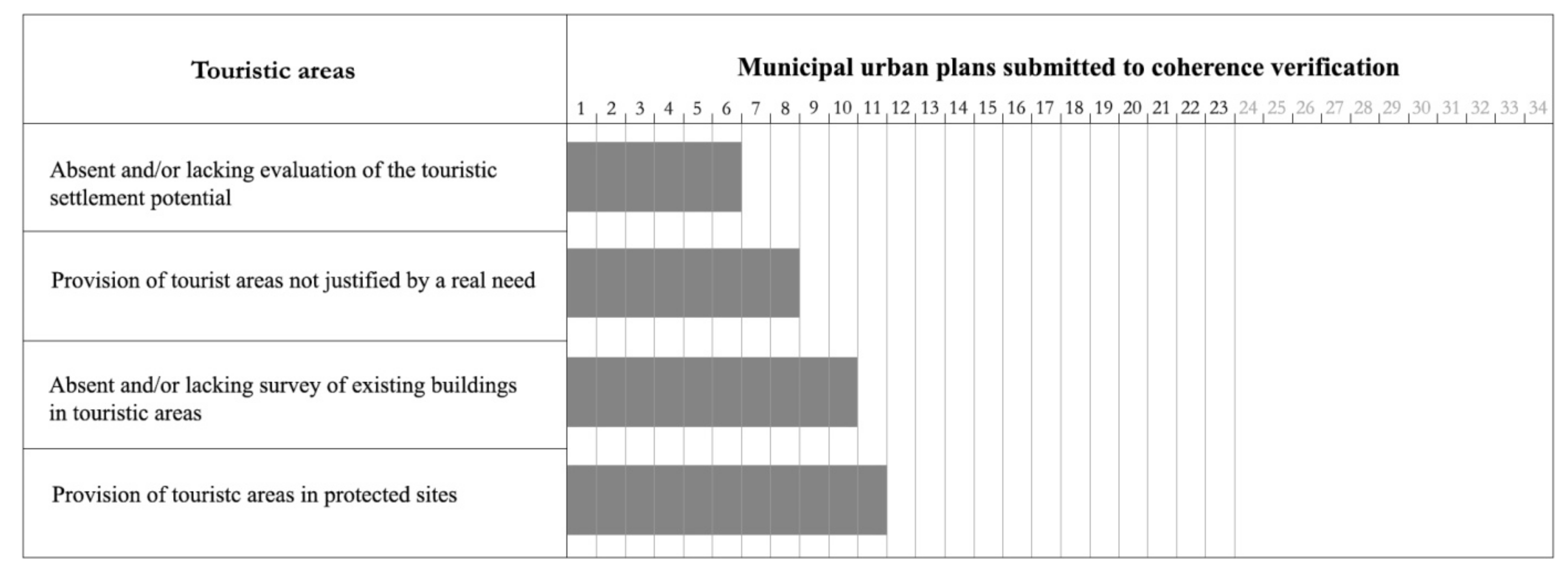

4.3.4. The Touristic Residential Areas

The RLP defines tourist settlements as those located mainly in the coastal area, which have been designed primarily for the non-resident population and differ for use, building type and services. In the municipal plan, the identification of new tourist areas (F zones) is allowed based on the assessment and classification of the coast capacity and on the environment and landscape features characteristic of the local context.

The common critical points concern the absence or the wrong evaluation of the maximum settlement capacity, calculated on the optimal coastal fruition; the provision of new F zones without explanation of the dimensioning and the gaps in the recognition of the existing buildings (

Figure 9).

Moreover, it has been highlighted that the location of the new areas for tourist settlements does not respect the criteria established by the RLP. In fact, it does not allow new transformations in the coastal area, except in case of integration of existing tourist settlements for the conversion of existing second houses into hotels, elimination of existing campsites from the coast and their conversion into hotel structures, and the transfer of existing settlements from the sensitive coastal zone to alternative areas already compromised.

The definition of the development areas for tourist purpose should be connected to the existing urban centres, with areas already build-up or regulated by effective detailed plans.

The analysis of the coherence checks has highlighted a remarkable number of coastal municipalities, specifically 11 out of 23, which planned the realization of new tourist settlements in protected areas according to the RLP.

4.3.5. The Agricultural and Productive Areas

The productive settlements of industrial, handcraft and commercial nature, the areas destined for large commercial distribution or to mining activities, identified in the RLP, are included in the municipal urban plan in the D Zone. The definition of the perimeters of the new productive zones should respect the criteria of completion and redefinition of already compromised areas, respecting the system of landscape values of the territory.

The analysis of coherence checks has highlighted the identification of new industrial and productive areas (D Zones), often not justified by a real need and in some cases in the absence of an adequate sizing assessment, which takes into account the existing activities and the opportunities still to be realised. As already discussed for other uses, there is a tendency to identify new areas for productive and general services uses in high environmental value and protected zones (

Figure 10).

The areas for agricultural uses (E Zones) should be identified according to an accurate evaluation of the real characters and conditions, of the environmental and landscape values and the attitude of land use.

While traditionally, the E Zone in the municipal plans was determined by the residual areas after the identification of buildable areas. Nowadays agricultural land is classified, according to the land use capacity (Land Capability), in sub-areas characterised by: a typical and specialized agricultural production (E1); a primary importance agricultural production (E2); an high fragmented land, which can be used for both agricultural-productive and residential purposes (E3); existing settlements, which can be used for the organization of rural centres (E4); marginal capacity for agricultural activity and inadequate conditions of environmental stability (E5). In many cases, this classification is not available or its regulation appears lacking and incomplete.

5. Discussion

There are many critical points in the process of updating and conforming municipal urban plans to the RLP, which have resulted in a limited number of municipalities that have achieved the goal. Several problems in the implementation of sustainable development and land protection objectives and the application of the guidelines and prescriptions of the RLP on a local scale have been highlighted. The reasons behind this standoff are different and, in part, can be linked to a widespread lack of political will, by local authorities, to apply protection rules that are not well accepted by the communities [

28]. The updating process of detailed plans for areas characterized by historic settlements has been more successful. The RLP only allows for maintenance and restoration of existing buildings until a detailed plan is approved. The verification of the boundary of historic settlements is subject to a further co-planning activity between the municipality and the regional authority based on detailed analysis to assess the real presence of elements of historical and architectural values to be preserved. This task has been completed by the most part of the 374 municipalities with a historic centre (90.6%). On the other hand, only 13.6% of municipalities have completed the process of drafting and approving the Detailed Plan for the Historic Centre.

According to the RLP, areas belonging to the maritime State property also require a detailed plan to regulate the destination of use and to identify those areas that can be assigned in concession to private parties for tourist and recreational activities. The drafting of a specific plan involves 72 coastal municipalities but, to date, only 15 have approved the Coastal Use Plan [

18].

In general, the urban municipal plans in compliance with RLP often include landscape contents that are not adequately developed and still adopt a strictly regulatory and traditional approach that does not fully reflect the philosophy of the ELC.

The limit of the qualitative method [

29], adopted to analyse the relevance of different landscape contents in municipal plans, is represented by the degree of subjectivity of the evaluation, which derives exclusively from the interpretation of the plan documents. Equally problematic is the lack of homogeneity in data and the necessary standardization of the analysis points, which did not affect the calibration of scores [

21,

30]. The assignment of ratings follows the presence or absence of a specific condition, just certifying when an outcome of interest is observed or not [

31]. Although it is clear that each specific judgment can be questioned, the method of analysis is effective for the research goal, which provides a simplified comparative overview of the case studies and allows to formulate or validate some hypotheses about the effectiveness of the integration of landscape approaches in the urban municipal plans. However, the possible limitations of this analysis are overcome by the additional investigations that support the final results.

Results highlighted an imbalance in the integration of the contents required by the RLP into local planning. On the one hand, the protection of historical, cultural and landscape resources is successfully achieved thanks to the involvement of the competent authorities (Ministry and Region) in the co-planning phase. This is sometimes due to a passive attitude, in which the municipality accepts the imposed measures and restrictions. On the other hand, there is rejection and conflict between administrations at different levels.

In the field of landscape valorization, a proactive role and a greater autonomy of the municipality is required. However, firstly, there is a cultural gap that leads to a lack of awareness about the opportunities offered by the landscape heritage from a socio-economic and sustainable development viewpoint, often emphasized in some small local contexts, where administrative and technical professionals do not have the appropriate expertise to manage and support the process. In addition, there is an evident difficulty in interpreting the complex process of redevelopment from an operational standpoint, defining actions that allow for their realization. This is partly due to the plan’s strict structure and approach, which fails to coordinate individual valorisation initiatives within a strategic and programmatic framework that would take into account the required time and resources.

The analysis of the coherence check has highlighted several critical issues related to the reorganization of the knowledge framework, due to the complexity of the required studies and competences in the downscaling from the regional to the municipal level, that cannot be underestimated. However, the main remarks concern the urban development and the private property regulation. The common factor is the failure to overcome the provisions of the local plans in force, which have contributed over time to create expectations, wrongly perceived as acquired rights by the citizens, which counter any downsizing of plan provisions. The planning adaptation process is therefore complicated by the difficulty of reconciling the objectives of environmental and landscape protection with the desire to safeguard the so-called “residual of the plan not realised” and the consolidated expectations of landowners. This is confirmed by the constant trend of guaranteeing the unrealised development provisions, considered as acquired, even in the absence of a real need [

25].

The revision of municipal urban plans is based on some fundamental principles with a prescriptive character related to the downsizing of construction provisions and sometimes the abandonment of development projects of a residential or tourist accommodation character in the coastal area. This leads to a lack of political willingness to make choices that are considered by the communities as unfavourable and disadvantageous for the development of the local tourism economy [

32]. Often private interests influence the action of local administrations, which prefer to avoid making decisions that can compromise their consensus.

In this sense, the action of the political decision-maker is fundamental to overcome the traditional systems of pre-established interests and operational practices that use planning as a tool to extract economic resources and exploit territorial capital. On the operational level, all this has produced further criticalities that have been summarised in the inability to conform municipal urban plans to the RLP and in the failure in the coherence check that does not allow completing the administrative process of adoption and coming into force of the plan [

32]. Although the RLP principles seem to be generally shared, these are not resulting in a sense of local responsibility, oriented to the protection of the territory, by the administrations and communities involved. They still pursue a planning practice based on the exploitation of territorial resources, with the aim of gain economic benefits, rather than related to the conservation and enhancement of the landscape heritage.

6. Conclusions

In the recognition of landscape values, the ELC promotes the use of a place-based approach, focusing on the investigation and interpretation of the specific relationship between territory and settled communities. The project of the territory is oriented to the preservation of common goods and heritage, following the construction of new bottom down community alliances stimulating a “consciousness of place” [

33,

34]. These considerations allow us to agree that the RLP of Sardinia has failed in the cultural effort to understand and take responsibility for the shared common good. It has not been able to create the pedagogical approach to the community that would have supported the coordination of the process and the participation in the construction of a vision [

35].

The complexity of the theme of landscape, in terms of planning application, reveals the distortive effects, even in the field of educational policies to the landscape, the territory, the cultural heritage, the common good. It shows all the problems and contradictions typical of an approach often ideologically and constricting.

The limited results obtained in the process of adaptation of the municipal instruments to the RLP also reveal a conflict between the region and the municipal administrations, which claim their autonomy in decision-making regarding the land uses conformation. If the current direction will not be changed, even the possible and necessary RLP revision and the extension to the inner areas of the island could not solve the complex problems of adaptation of municipal planning.

A final reflection on the re-writing of the regional urban law should be provided, beyond the technical aspect, related to the hypothesis of a bi-partition of the general plan into structural and operative components that could simplify the adjustment process, distinguishing the phase of analysis and interpretation of the landscape invariants and values of the territory from the definition of the programmatic framework of actions of protection, valorisation, recovery and creation of landscapes.

Recently, the region of Sardinia has changed the procedures for the drafting, adoption and approval of the municipal urban plan in an attempt to simplify the process and define a shared timetable (art.23 of R.L. n.1/2019). The main innovations concern the presentation to the Council, within 6 months from the launch of the procedure, of the municipal urban plan in a preliminary version, which contains the specialized analysis and the main strategies and guidelines for planning. The procedures for the acquisition of the advisory opinions of the competent regional authorities could be supported by the establishment of the co-planning conference, which, within a deadline defined by law, formulates observations on the plan before final approval by the municipal council. The establishment of clear timelines for municipal plan drafting and approval, along with close collaboration and support from the regional technical office, could simplify the process of adaptation of tools. However, a change in the “cultural” framework to address critical participation issues could support recognition of the community value system.

However, there is still the problem of the absence of public debate [

36] in general, and especially on territorial and landscape planning, whose lack as an effect of a plural mechanism generates difficulties in applying the prescriptions of the RLP at the local scale and in defining project scenarios.

The lack of coherence and coordination of the RLP with regional legislative acts, also due to the lack of discussion and consequent approval of the new regional urban planning law, contributes to create an uncertain situation in which local authorities operate in the territorial government. The incomplete approach of the RLP, with the priority assigned to the regulation of the coastal territory, has contributed to create an imbalance between the latter and the inner areas, damaging the consolidated historical relationships. The Sardinian population has not historically been attracted by the coasts, considered unproductive territorial areas for the economy, essentially based on the agro-pastoral sector, and later acquired the awareness of the economic potential and the touristic vocation of the territory, also thanks to the success of some experiences of touristic real estate development, in particular those of Costa Smeralda. Public opinion has often been divided on the outcomes of these transformations, in some cases reading these projects as operations of “colonization”, in others hoping for the promotion of a new model of development, emphasizing the positive socio-economic and employment effects and neglecting the effects on the landscape and territorial resources.

The gradual introduction of the environmental and landscape constraints, as a result of national legislation and, subsequently, of the entry into force of the RLP, has generally not been well accepted by local communities. The negative perception of the landscape plan, as an obstacle to the building development initiatives of local entrepreneurs, has been further emphasised by the lack of adaptation of municipal urban plans and by the extension of the temporary restrictive regulations, which have been in force for more than fifteen years. This is due, in part, to a cultural problem linked to the fact that communities and local decision-makers, erroneously, believe that the development capacity of land near the coast is directly linked to economic development and tourism. The regional leading group, responsible also for the political message that the RLP should have given in the direction of a greater political and cultural involvement of local communities, has not had the strength to support an alternative model of social and economic development. At the same time, it has neglected the acquisition of self-recognition processes specific to different contexts by local communities. The diffusion of these ideas and the belief in the collective interest of the proposed actions could not be pursue only with impositions and constraints but should follow criteria of shared choices.

This poor information has found a substantial basis in the radical change produced by Sardinian society itself, reflecting a more general social change that we have been experiencing for a long time.

The landscape instrument, more than others, should have integrated the “genius loci”, by activating the individual and collective drivers of the communities, strengthening those territorial conditions that make possible new sustainable developments.

The constraint represents a key factor on which focus to avoid possible elements of the crisis due to the direct effect on the community cohesion and the creation of territorial social capital. The inhabitants should be able to identify the value that is preserved by the constraint and can be supported by relational practices to increase also the trust towards the institution and the planning instrument [

33].

At the same time, a rigid representation of identity that implies a vision of development based on the idea of an immutable patrimony denies the co-evolutionary relationship with the settled community [

34,

37]. The desire to preserve a sort of timelessness does not make communities exempt from the phenomena of globalization and from the transformations induced in the socio-economic structure which, albeit to a lesser extent, also involve contexts that are usually reluctant. This translates into a weakening of local planning, which follows the patterns prearranged and spread by global networks [

20].

The protection rules and the widespread “care” of the territory that has allowed us to pass down, in a long time of history, the contexts as we know them today [

12] must be discerned within the process of self-recognition of the value system of the community, to reinforce and re-guarantee that social pact based not only on regulatory tools but also on planning, economic, financial, organizational and cultural tools [

38] that are useful to encourage new territorialisation, as an inevitable consequence of contemporaneity.