Brown Macroalgae as Valuable Food Ingredients

Abstract

:1. Introduction

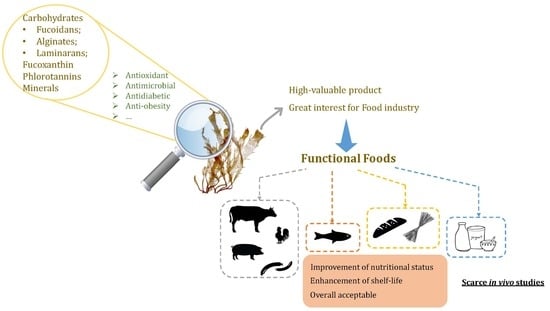

2. Chemical Particularities of Brown Macroalgae

2.1. Polysaccharides

2.2. Phlorotannins

2.3. Fucoxanthin

2.4. Minerals

3. Use of Brown Macroalgae as Food Ingredient

3.1. Fucus vesiculosus

3.2. Himanthalia elongata

3.3. Undaria pinnatifida

3.4. Ascophyllum Nodosum

3.5. Laminaria sp.

4. Future Considerations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References and Note

- Cofrades, S.; López-Lopez, I.; Solas, M.; Bravo, L.; Jimenez-Colmenero, F. Influence of different types and proportions of added edible seaweeds on characteristics of low-salt gel/emulsion meat systems. Meat Sci. 2008, 79, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wijesinghe, W.; Jeon, Y.J. Enzyme-assistant extraction (EAE) of bioactive components: A useful approach for recovery of industrially important metabolites from seaweeds: A review. Fitoterapia 2012, 83, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, S.M.; Carvalho, L.; Silva, P.; Rodrigues, M.; Pereira, O.; Pereira, L.; De Carvalho, L. Bioproducts from Seaweeds: A Review with Special Focus on the Iberian Peninsula. Curr. Org. Chem. 2014, 18, 896–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Circuncisão, A.R.; Catarino, M.D.; Cardoso, S.M.; Silva, A.M.S. Minerals from Macroalgae Origin: Health Benefits and Risks for Consumers. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, S.M.; Pereira, O.R.; Seca, A.M.L.; Pinto, D.C.G.A.; Silva, A.M.S. Seaweeds as Preventive Agents for Cardiovascular Diseases: From Nutrients to Functional Foods. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 6838–6865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Willcox, D.C.; Willcox, B.J.; Todoriki, H.; Suzuki, M. The Okinawan diet: Health implications of a low-calorie, nutrient-dense, antioxidant-rich dietary pattern low in glycemic load. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2009, 28, 500S–516S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blank, C. The Rise of Seaweed. Available online: https://www.seafoodsource.com/features/the-rise-of-seaweed (accessed on 5 June 2019).

- Lorenzo, J.M.; Agregán, R.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Franco, D.; Carballo, J.; ¸Sahin, S.; Lacomba, R.; Barba, F.J. Proximate Composition and Nutritional Value of three macroalgae: Ascophyllum nodosum, Fucus vesiculosus and Bifurcaria bifurcata. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Abu-Ghannam, N. Bioactive potential and possible health effects of edible brown seaweeds. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 22, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Catarino, M.D.; Silva, A.M.S.; Cardoso, S.M. Phycochemical Constituents and Biological Activities of Fucus spp. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catarino, M.D.; Silva, A.M.S.; Cardoso, S.M. Fucaceae: A Source of Bioactive Phlorotannins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J. Seaweed on Track to Become Europe’s Next Big Superfood Trend. Available online: https://www.seafoodsource.com/news/food-safety-health/seaweed-on-track-to-become-europe-s-next-big-superfood-trend (accessed on 6 July 2019).

- Seaweed-Flavoured Food and Drink Launches Increased by 147% in Europe between 2011 and 2015. Available online: http://0-www-mintel-com.brum.beds.ac.uk/press-centre/food-and-drink/seaweed-flavoured-food-and-drink-launches-increased-by-147-in-europe-between-2011-and-2015 (accessed on 23 Aug 2019).

- CEVA. Edible Seaweed and French Regulation; 2014.

- Pádua, D.; Rocha, E.; Gargiulo, D.; Ramos, A.; Ramos, A. Bioactive compounds from brown seaweeds: Phloroglucinol, fucoxanthin and fucoidan as promising therapeutic agents against breast cancer. Phytochem. Lett. 2015, 14, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, A.; Khalid, S.; Usman, A.; Hussain, Z.; Wang, Y. Algal Polysaccharides, Novel Application, and Outlook. In Algae Based Polymers, Blends, and Composites; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 115–153. [Google Scholar]

- Susanto, E.; Fahmi, A.S.; Abe, M.; Hosokawa, M.; Miyashita, K. Lipids, Fatty Acids, and Fucoxanthin Content from Temperate and Tropical Brown Seaweeds. Aquat. Procedia 2016, 7, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.F.; Abreu, H.; Silva, A.M.; Cardoso, S.M. Effect of Oven-Drying on the Recovery of Valuable Compounds from Ulva rigida, Gracilaria sp. and Fucus vesiculosus. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charoensiddhi, S.; Lorbeer, A.J.; Lahnstein, J.; Bulone, V.; Franco, C.M.; Zhang, W. Enzyme-assisted extraction of carbohydrates from the brown alga Ecklonia radiata: Effect of enzyme type, pH and buffer on sugar yield and molecular weight profiles. Process. Biochem. 2016, 51, 1503–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Peng, C.; Zhou, H.; Lin, Z.; Lin, G.; Chen, S.; Li, P. Nutritional Composition and Assessment of Gracilaria lemaneiformis Bory. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2006, 48, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioux, L.E.; Turgeon, S.; Beaulieu, M. Characterization of polysaccharides extracted from brown seaweeds. Carbohydr. Polym. 2007, 69, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Je, J.Y.; Park, P.J.; Kim, E.K.; Park, J.S.; Yoon, H.D.; Kim, K.R.; Ahn, C.B. Antioxidant activity of enzymatic extracts from the brown seaweed Undaria pinnatifida by electron spin resonance spectroscopy. LWT 2009, 42, 874–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiener, P.; Black, K.D.; Stanley, M.S.; Green, D.H. The seasonal variation in the chemical composition of the kelp species Laminaria digitata, Laminaria hyperborea, Saccharina latissima and Alaria esculenta. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2014, 27, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgougnon, N.; Deslandes, E. Carbohydrates from Seaweeds. In Seaweed in Health and Disease Prevention; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 223–274. [Google Scholar]

- Horn, S.J.; Moen, E.; Østgaard, K. Direct determination of alginate content in brown algae by near infra-red (NIR) spectroscopy. J. Appl. Phycol. 1999, 11, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwanl, A.; Davies, G.; Fataftah, A.; Ghabbour, E.A.; Jansen, S.A.; Willey, R.J. Isolation of humic acid from the brown algae Ascophyllum nodosum, Fucus vesiculosus, Laminaria saccharina and the marine angiosperm Zostera marina. J. Appl. Phycol. 1997, 8, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draget, K.; Skjakbrak, G.; Smidsrod, O. Alginic acid gels: The effect of alginate chemical composition and molecular weight. Carbohydr. Polym. 1994, 25, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolucci, M.; Fabbrocini, A.; Grazia, M.; Varricchio, E.; Cocci, E. Development of Biopolymers as Binders for Feed for Farmed Aquatic Organisms. Aquaculture 2012, 1, 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee, I.A.; Seal, C.J.; Wilcox, M.; Dettmar, P.W.; Pearson, J.P. Applications of Alginates in Food. In Alginates: Biology and Applications; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 13, pp. 211–228. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, E.M.; Allsopp, P.J.; Magee, P.J.; Gill, C.I.R.; Nitecki, S.; Strain, C.R. Seaweed and human health. Nutr. Rev. 2014, 72, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherry, P.; Yadav, S.; Strain, C.R.; Allsopp, P.J.; McSorley, E.M.; Ross, R.P.; Stanton, C. Prebiotics from Seaweeds: An Ocean of Opportunity? Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruhn, A.; Janicek, T.; Manns, D.; Nielsen, M.M.; Balsby, T.J.S.; Meyer, A.S.; Rasmussen, M.B.; Hou, X.; Saake, B.; Göke, C.; et al. Crude fucoidan content in two North Atlantic kelp species, Saccharina latissima and Laminaria digitata—Seasonal variation and impact of environmental factors. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2017, 29, 3121–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ale, M.T.; Mikkelsen, J.D.; Meyer, A.S. Important Determinants for Fucoidan Bioactivity: A Critical Review of Structure-Function Relations and Extraction Methods for Fucose-Containing Sulfated Polysaccharides from Brown Seaweeds. Mar. Drugs 2011, 9, 2106–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ale, M.T.; Meyer, A.S. Fucoidans from brown seaweeds: An update on structures, extraction techniques and use of enzymes as tools for structural elucidation. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 8131–8141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xing, M.; Cao, Q.; Ji, A.; Liang, H.; Song, S. Biological Activities of Fucoidan and the Factors Mediating Its Therapeutic Effects: A Review of Recent Studies. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veena, C.K.; Josephine, A.; Preetha, S.P.; Varalakshmi, P. Beneficial role of sulfated polysaccharides from edible seaweed Fucus vesiculosus in experimental hyperoxaluria. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 1552–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Wen, K.; Gao, X.; Liu, Y. Hypolipidemic effect of fucoidan from Laminaria japonica in hyperlipidemic rats. Pharm. Biol. 2010, 48, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Liu, X.; Hao, J.; Cai, C.; Fan, F.; Dun, Y.; Zhao, X.; Liu, X.; Li, C.; Yu, G. In vitro and in vivo hypoglycemic effects of brown algal fucoidans. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 82, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.J.; Yoon, K.Y.; Lee, B.Y. Fucoidan regulate blood glucose homeostasis in C57BL/KSJ m+/+db and C57BL/KSJ db/db mice. Fitoterapia 2012, 83, 1105–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadam, S.U.; Tiwari, B.K.; Donnell, C.P.O. Extraction, structure and biofunctional activities of laminarin from brown algae. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdt, S.L.; Kraan, S. Bioactive compounds in seaweed: Functional food applications and legislation. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2011, 23, 543–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroney, N.C.; O’Grady, M.N.; Lordan, S.; Stanton, C.; Kerry, J.P. Seaweed Polysaccharides (Laminarin and Fucoidan) as Functional Ingredients in Pork Meat: An Evaluation of Anti-Oxidative Potential, Thermal Stability and Bioaccessibility. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 2447–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Deville, C.; Damas, J.; Forget, P.; Dandrifosse, G.; Peulen, O. Laminarin in the dietary fibre concept. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2004, 84, 1030–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkeborg, M.; Cheong, L.Z.; Gianfico, C.; Sztukiel, K.M.; Kristensen, K.; Glasius, M.; Xu, X.; Guo, Z. Alginate oligosaccharides: Enzymatic preparation and antioxidant property evaluation. Food Chem. 2014, 164, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Shi, X.Y.; Bi, D.C.; Fang, W.S.; Wei, G.B.; Xu, X. Alginate-Derived Oligosaccharide Inhibits Neuroinflammation and Promotes Microglial Phagocytosis of β-Amyloid. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 5828–5846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Xue, C.; Ning, Y.; Li, Z.; Xu, J. Acute antihypertensive effects of fucoidan oligosaccharides prepared from Laminaria japonica on renovascular hypertensive rats. J. Ocean Univ. China(Nat. Sci.) 2004, 34, 560–564. [Google Scholar]

- Koivikko, R.; Loponen, J.; Honkanen, T.; Jormalainen, V. Contents of soluble, cell-wall-bound and exuded phlorotannins in the brown alga Fucus vesiculosus, with implications on their ecological functions. J. Chem. Ecol. 2005, 31, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbs, T.I.; Zvyagintseva, T.N. Phlorotannins are Polyphenolic Metabolites of Brown Algae. Russ. J. Mar. Biol. 2018, 44, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catarino, M.D.; Silva, A.M.S.; Mateus, N.; Cardoso, S.M. Optimization of Phlorotannins Extraction from Fucus vesiculosus and Evaluation of Their Potential to Prevent Metabolic Disorders. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijesekara, I.; Kim, S.-K.; Li, Y.-X.; Li, Y. Phlorotannins as bioactive agents from brown algae. Process. Biochem. 2011, 46, 2219–2224. [Google Scholar]

- Neto, R.T.; Marçal, C.; Queirós, A.S.; Abreu, H.; Silva, A.M.S.; Cardoso, S.M. Screening of Ulva rigida, Gracilaria sp., Fucus vesiculosus and Saccharina latissima as Functional Ingredients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan, A.; O’Callaghan, Y.; O’Grady, M.; Queguineur, B.; Hanniffy, D.; Troy, D.; Kerry, J.; O’Brien, N. In vitro and cellular antioxidant activities of seaweed extracts prepared from five brown seaweeds harvested in spring from the west coast of Ireland. Food Chem. 2011, 126, 1064–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaragozá, M.C.; López, D.; Sáiz, M.P.; Poquet, M.; Pérez, J.; Puig-Parellada, P.; Màrmol, F.; Simonetti, P.; Gardana, C.; Lerat, Y.; et al. Toxicity and Antioxidant Activity in Vitro and in Vivo of Two Fucus vesiculosus Extracts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 7773–7780. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, M.-C.; Anguenot, R.; Fillion, C.; Beaulieu, M.; Bérubé, J.; Richard, D. Effect of a commercially-available algal phlorotannins extract on digestive enzymes and carbohydrate absorption in vivo. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 3026–3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, M.E.; Couture, P.; Lamarche, B. A randomised crossover placebo-controlled trial investigating the effect of brown seaweed (Ascophyllum nodosum and Fucus vesiculosus) on postchallenge plasma glucose and insulin levels in men and women. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 36, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldrick, F.R.; McFadden, K.; Ibars, M.; Sung, C.; Moffatt, T.; Megarry, K.; Thomas, K.; Mitchell, P.; Wallace, J.M.W.; Pourshahidi, L.K.; et al. Impact of a (poly)phenol-rich extract from the brown algae Ascophyllum nodosum on DNA damage and antioxidant activity in an overweight or obese population: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 108, 688–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corona, G.; Ji, Y.; Anegboonlap, P.; Hotchkiss, S.; Gill, C.; Yaqoob, P.; Spencer, J.P.E.; Rowland, I. Gastrointestinal modifications and bioavailability of brown seaweed phlorotannins and effects on inflammatory markers. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 1240–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Collén, J.; Davison, I.R. Reactive oxygen metabolism in intertidal Fucus spp. (Phaeophyceae). J. Phycol. 1999, 35, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikami, K.; Hosokawa, M. Biosynthetic Pathway and Health Benefits of Fucoxanthin, an Algae-Specific Xanthophyll in Brown Seaweeds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 13763–13781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Peng, J.; Yuan, J.-P.; Wu, C.-F.; Wang, J.-H. Fucoxanthin, a Marine Carotenoid Present in Brown Seaweeds and Diatoms: Metabolism and Bioactivities Relevant to Human Health. Mar. Drugs 2011, 9, 1806–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, H.; Hosokawa, M.; Sashima, T.; Murakami-Funayama, K.; Miyashita, K. Anti-obesity and anti-diabetic effects of fucoxanthin on diet-induced obesity conditions in a murine model. Mol. Med. Rep. 2009, 2, 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, H.; Hosokawa, M.; Sashima, T.; Takahashi, N.; Kawada, T.; Miyashita, K. Fucoxanthin and its metabolite, fucoxanthinol, suppress adipocyte differentiation in 3T3-L1 cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2006, 18, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, H.; Hosokawa, M.; Sashima, T.; Funayama, K.; Miyashita, K. Fucoxanthin from edible seaweed, Undaria pinnatifida, shows antiobesity effect through UCP1 expression in white adipose tissues. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 332, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, A.W.; Kim, W.K. The effect of fucoxanthin rich power on the lipid metabolism in rats with a high fat diet. Nutr. Res. Pr. 2013, 7, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Whelton, P.K. Sodium, Potassium, Blood Pressure, and Cardiovascular Disease in Humans. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2014, 16, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaustein, M.P.; Leenen, F.H.H.; Chen, L.; Golovina, V.A.; Hamlyn, J.M.; Pallone, T.L.; Van Huysse, J.W.; Zhang, J.; Gil Wier, W. How NaCl raises blood pressure: A new paradigm for the pathogenesis of salt-dependent hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2011, 302, H1031–H1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrea-Marín, M.; Pomares-Alfonso, M.; Gómez-Juaristi, M.; Sánchez-Muniz, F.; De La Rocha, S.R. Validation of an ICP-OES method for macro and trace element determination in Laminaria and Porphyra seaweeds from four different countries. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2010, 23, 814–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreda-Piñeiro, J.; Alonso-Rodríguez, E.; López-Mahía, P.; Muniategui-Lorenzo, S.; Prada-Rodríguez, D.; Moreda-Piñeiro, A.; Bermejo-Barrera, P. Development of a new sample pre-treatment procedure based on pressurized liquid extraction for the determination of metals in edible seaweed. Anal. Chim. Acta 2007, 598, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruperez, P. Mineral content of edible marine seaweeds. Food Chem. 2002, 79, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, L.; Lima, E.; Neto, A.I.; Marcone, M.; Baptista, J. Health-promoting ingredients from four selected Azorean macroalgae. Food Res. Int. 2016, 89, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitschke, U.; Ruth, A.A.; Dixneuf, S.; Stengel, D.B. Molecular iodine emission rates and photosynthetic performance of different thallus parts of Laminaria digitata (Phaeophyceae) during emersion. Planta 2011, 233, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacArtain, P.; Gill, C.I.; Brooks, M.; Campbell, R.; Rowland, I.R. Nutritional Value of Edible Seaweeds. Nutr. Rev. 2007, 65, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellarosa, N.; Laghi, L.; Martinsdóttir, E.; Jónsdóttir, R.; Sveinsdóttir, K. Enrichment of convenience seafood with omega-3 and seaweed extracts: Effect on lipid oxidation. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 62, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Rubio, M.E.; Serrano, J.; Borderias, J.; Saura-Calixto, F. Technological Effect and Nutritional Value of Dietary Antioxidant Fucus Fiber Added to Fish Mince. J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 2011, 20, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Jónsdóttir, R.; Kristinsson, H.G.; Thorkelsson, G.; Jacobsen, C.; Hamaguchi, P.Y.; Ólafsdóttir, G. Inhibition of haemoglobin-mediated lipid oxidation in washed cod muscle and cod protein isolates by Fucus vesiculosus extract and fractions. Food Chem. 2010, 123, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jónsdóttir, R.; Geirsdóttir, M.; Hamaguchi, P.Y.; Jamnik, P.; Kristinsson, H.G.; Undeland, I. The ability of in vitro antioxidant assays to predict the efficiency of a cod protein hydrolysate and brown seaweed extract to prevent oxidation in marine food model systems. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 2125–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halldorsdottir, S.M.; Kristinsson, H.G.; Sveinsdóttir, H.; Thorkelsson, G.; Hamaguchi, P.Y. The effect of natural antioxidants on haemoglobin-mediated lipid oxidation during enzymatic hydrolysis of cod protein. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 914–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halldorsdottir, S.M.; Sveinsdóttir, H.; Gudmundsdóttir, Á.; Thorkelsson, G.; Kristinsson, H.G. High quality fish protein hydrolysates prepared from by-product material with Fucus vesiculosus extract. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 9, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadağ, A.; Hermund, D.B.; Jensen, L.H.S.; Andersen, U.; Jónsdóttir, R.; Kristinsson, H.G.; Alasalvar, C.; Jacobsen, C. Oxidative stability and microstructure of 5% fish-oil-enriched granola bars added natural antioxidants derived from brown alga Fucus vesiculosus. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2017, 119, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermund, D.B.; Karadağ, A.; Andersen, U.; Jónsdóttir, R.; Kristinsson, H.G.; Alasalvar, C.; Jacobsen, C. Oxidative Stability of Granola Bars Enriched with Multilayered Fish Oil Emulsion in the Presence of Novel Brown Seaweed Based Antioxidants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 8359–8368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hermund, D.B.; Yesiltas, B.; Honold, P.; Jónsdóttir, R.; Kristinsson, H.G.; Jacobsen, C. Characterisation and antioxidant evaluation of Icelandic F. vesiculosus extracts in vitro and in fish-oil-enriched milk and mayonnaise. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 19, 828–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honold, P.J.; Jacobsen, C.; Jónsdóttir, R.; Kristinsson, H.G.; Hermund, D.B. Potential seaweed-based food ingredients to inhibit lipid oxidation in fish-oil-enriched mayonnaise. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2016, 242, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agregán, R.; Franco, D.; Carballo, J.; Tomasevic, I.; Barba, F.J.; Gómez, B.; Muchenje, V.; Lorenzo, J.M. Shelf life study of healthy pork liver pâté with added seaweed extracts from Ascophyllum nodosum, Fucus vesiculosus and Bifurcaria bifurcata. Food Res. Int. 2018, 112, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan, A.M.; O’Callaghan, Y.C.; O’Grady, M.N.; Waldron, D.S.; Smyth, T.J.; O’Brien, N.M.; Kerry, J.P. An examination of the potential of seaweed extracts as functional ingredients in milk. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2014, 67, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, A.; O’Grady, M.; O’Callaghan, Y.; Smyth, T.; O’Brien, N.; Kerry, J. Seaweed extracts as potential functional ingredients in yogurt. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 37, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poveda-Castillo, G.D.C.; Rodrigo, D.; Martínez, A.; Pina-Pérez, M.C. Bioactivity of Fucoidan as an Antimicrobial Agent in a New Functional Beverage. Beverages 2018, 4, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arufe, S.; Della Valle, G.; Chiron, H.; Chenlo, F.; Sineiro, J.; Moreira, R. Effect of brown seaweed powder on physical and textural properties of wheat bread. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2018, 244, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, C.; Hartvigsen, K.; Lund, P.; Thomsen, M.K.; Skibsted, L.H.; Adler-Nissen, J.; Hølmer, G.; Meyer, A.S. Oxidation in fish oil-enriched mayonnaise3. Assessment of the influence of the emulsion structure on oxidation by discriminant partial least squares regression analysis. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2000, 211, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agregán, R.; Barba, F.J.; Gavahian, M.; Franco, D.; Khaneghah, A.M.; Carballo, J.; Ferreira, I.C.F.; Barretto, A.C.S.; Lorenzo, J.M. Fucus vesiculosus extracts as natural antioxidants for improvement of physicochemical properties and shelf life of pork patties formulated with oleogels. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 4561–4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cofrades, S.; López-Lopez, I.; Ruiz-Capillas, C.; Triki, M.; Jimenez-Colmenero, F. Quality characteristics of low-salt restructured poultry with microbial transglutaminase and seaweed. Meat Sci. 2011, 87, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Lopez, I.; Bastida, S.; Ruiz-Capillas, C.; Bravo, L.; Larrea, M.T.; Sánchez-Muniz, F.; Cofrades, S.; Jimenez-Colmenero, F. Composition and antioxidant capacity of low-salt meat emulsion model systems containing edible seaweeds. Meat Sci. 2009, 83, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Martín, F.; López-López, I.; Cofrades, S.; Colmenero, F.J. Influence of adding Sea Spaghetti seaweed and replacing the animal fat with olive oil or a konjac gel on pork meat batter gelation. Potential protein/alginate association. Meat Sci. 2009, 83, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, A.R.S.; Benedi, J.; González-Torres, L.; Olivero-David, R.; Bastida, S.; Sánchez-Reus, M.I.; González-Muñoz, M.J.; Sánchez-Muniz, F.J. Effects of diet enriched with restructured meats, containing Himanthalia elongata, on hypercholesterolaemic induction, CYP7A1 expression and antioxidant enzyme activity and expression in growing rats. Food Chem. 2011, 129, 1623–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Torres, L.; Churruca, I.; Schultz Moreira, A.R.; Bastida, S.; Benedí, J.; Portillo, M.P.; Sánchez-Muniz, F.J. Effects of restructured pork containing Himanthalia elongata on adipose tissue lipogenic and lipolytic enzyme expression of normo- and hypercholesterolemic rats. J. Nutrigenet. Nutr. 2012, 5, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Colmenero, F.; Cofrades, S.; López-Lopez, I.; Ruiz-Capillas, C.; Pintado, T.; Solas, M. Technological and sensory characteristics of reduced/low-fat, low-salt frankfurters as affected by the addition of konjac and seaweed. Meat Sci. 2010, 84, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S.; Abu-Ghannam, N. Enhancement of the phytochemical and fibre content of beef patties with Himanthalia elongata seaweed. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 48, 2239–2249. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, S.; Abu-Ghannam, N. Incorporation of Himanthalia elongata seaweed to enhance the phytochemical content of breadsticks using response surface methodology (RSM). Int. Food Res. J. 2013, 20, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar]

- Rico, D.; De Linaje, A.A.; Herrero, A.; Asensio-Vegas, C.; Miranda, J.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C.; De Luis, D.A.; Martin-Diana, A.B. Carob by-products and seaweeds for the development of functional bread. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2018, 42, e13700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuñez, M.; Picon, A. Seaweeds in yogurt and quark supplementation: Influence of five dehydrated edible seaweeds on sensory characteristics. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 52, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Lopez, I.; Cofrades, S.; Jimenez-Colmenero, F. Low-fat frankfurters enriched with n−3 PUFA and edible seaweed: Effects of olive oil and chilled storage on physicochemical, sensory and microbial characteristics. Meat Sci. 2009, 83, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Lopez, I.; Cofrades, S.; Ruiz-Capillas, C.; Jimenez-Colmenero, F. Design and nutritional properties of potential functional frankfurters based on lipid formulation, added seaweed and low salt content. Meat Sci. 2009, 83, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, A.R.S.; Benedi, J.; Bastida, S.; Sánchez-Reus, I.; Sánchez-Muniz, F.J. Nori- and sea spaghetti- but not wakame-restructured pork decrease the hypercholesterolemic and liver proapototic short-term effects of high-dietary cholesterol consumption. Nutrición Hospitalaria 2013, 28, 1422–1429. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, M.R.; Choi, S.H. Quality Characteristics of Pork Patties Added with Seaweed Powder. Korean J. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2012, 32, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Lopez, I.; Cofrades, S.; Yakan, A.; Solas, M.; Jimenez-Colmenero, F. Frozen storage characteristics of low-salt and low-fat beef patties as affected by Wakame addition and replacing pork backfat with olive oil-in-water emulsion. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 1244–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Lopez, I.; Cofrades, S.; Cañeque, V.; Díaz, M.; Lopez, O.; Jimenez-Colmenero, F. Effect of cooking on the chemical composition of low-salt, low-fat Wakame/olive oil added beef patties with special reference to fatty acid content. Meat Sci. 2011, 89, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, K.; Ishihara, K.; Oyamada, C.; Sato, A.; Fukushi, A.; Arakane, T.; Motoyama, M.; Yamazaki, M.; Mitsumoto, M. Effects of Fucoxanthin Addition to Ground Chicken Breast Meat on Lipid and Colour Stability during Chilled Storage, before and after Cooking. Asian Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2008, 21, 1067–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhasankar, P.; Ganesan, P.; Bhaskar, N.; Hirose, A.; Stephen, N.; Gowda, L.R.; Hosokawa, M.; Miyashita, K. Edible Japanese seaweed, wakame (Undaria pinnatifida) as an ingredient in pasta: Chemical, functional and structural evaluation. Food Chem. 2009, 115, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.S.; González-Torres, L.; Olivero-David, R.; Bastida, S.; Benedi, J.; Sánchez-Muniz, F.J. Wakame and Nori in Restructured Meats Included in Cholesterol-enriched Diets Affect the Antioxidant Enzyme Gene Expressions and Activities in Wistar Rats. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2010, 65, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalic, L.M.; Berkovic, K. The influence of algae addition on physicochemical properties of cottage cheese. Milchwiss. Milk Sci. Int. 2005, 60, 151–154. [Google Scholar]

- Dierick, N.; Ovyn, A.; De Smet, S. Effect of feeding intact brown seaweed Ascophyllum nodosum on some digestive parameters and on iodine content in edible tissues in pigs. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2009, 89, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.; Fairclough, A.; Mahadevan, K.; Paxman, J. Ascophyllum nodosum enriched bread reduces subsequent energy intake with no effect on post-prandial glucose and cholesterol in healthy, overweight males. A pilot study. Appetite 2012, 58, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Peteiro, C. Alginate Production from Marine Macroalgae, with Emphasis on Kelp Farming. In Alginates and Their Biomedical Applications; Rehm, B.H.A., Moradali, F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 27–66. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, S.; Ranz, D.; He, M.L.; Burkard, S.; Lukowicz, M.V.; Reiter, R.; Arnold, R.; Le Deit, H.; David, M.; Rambeck, W. A Marine algae as natural source of iodine in the feeding of freshwater fish—A new possibility to improve iodine supply of man. Rev. Med. Vet. (Toulouse). 2003, 154, 645–648. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, A.R.; Gonçalves, A.; Colen, R.; Nunes, M.L.; Dinis, M.T.; Dias, J. Dietary macroalgae is a natural and effective tool to fortify gilthead seabream fillets with iodine: Effects on growth, sensory quality and nutritional value. Aquaculture 2015, 437, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.R.; Gonçalves, A.; Bandarra, N.; Nunes, M.L.; Dinis, M.T.; Dias, J.; Rema, P. Natural fortification of trout with dietary macroalgae and selenised-yeast increases the nutritional contribution in iodine and selenium. Food Res. Int. 2017, 99, 1103–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, M.L.; Hollwich, W.; Rambeck, W.A. Supplementation of algae to the diet of pigs: A new possibility to improve the iodine content in the meat. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2002, 86, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajauria, G.; Draper, J.; McDonnell, M.; O’Doherty, J. Effect of dietary seaweed extracts, galactooligosaccharide and vitamin E supplementation on meat quality parameters in finisher pigs. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 37, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroney, N.; O’Grady, M.; O’Doherty, J.; Kerry, J. Effect of a brown seaweed (Laminaria digitata) extract containing laminarin and fucoidan on the quality and shelf-life of fresh and cooked minced pork patties. Meat Sci. 2013, 94, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.W.; Choi, J.H.; Choi, Y.S.; Han, D.J.; Kim, H.Y.; Lee, M.A.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, C.J. Effects of Sea Tangle (Lamina japonica) Powder on Quality Characteristics of Breakfast Sausages. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2010, 30, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.H.; Lim, H.-S. Effects of Sea Tangle-added Patty on Postprandial Serum Lipid Profiles and Glucose in Borderline Hypercholesterolemic Adults. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 43, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koval, P.V.; Shulgin, Y.P.; Lazhentseva, L.Y.; Zagorodnaya, G.I. Probiotic drinks containing iodine. Molochnaya Promyshlennost 2005, 6, 38–39. [Google Scholar]

- Indrawati, R.; Sukowijoyo, H.; Indriatmoko; Wijayanti, R.D.E.; Limantara, L. Encapsulation of Brown Seaweed Pigment by Freeze Drying: Characterization and its Stability during Storage. Procedia Chem. 2015, 14, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Einarsdóttir, Á.M. Edible Seaweed for Taste Enhancement and Salt Replacement by Enzymatic Methods. MSc Thesis, University of Iceland, Reykjavík, Iceland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, Y.S.; Bae, H.N.; Eom, S.H.; Lim, K.S.; Yun, I.H.; Chung, Y.H.; Jeon, J.M.; Kim, H.W.; Lee, M.S.; Lee, Y.B.; et al. Removal of off-flavors from sea tangle (Laminaria japonica) extract by fermentation with Aspergillus oryzae. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 121, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Escrig, A.; Sánchez-Muniz, F.J. Dietary fibre from edible seaweeds: Chemical structure, physicochemical properties and effects on cholesterol metabolism. Nutr. Res. 2000, 20, 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asai, A.; Sugawara, T.; Ono, H.; Nagao, A. Biotransformation of fucoxanthinol into amarouciaxanthin a in mice and hepg2 cells: Formation and cytotoxicity of fucoxanthin metabolites. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2004, 32, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugawara, T.; Baskaran, V.; Nagao, A.; Tsuzuki, W. Brown Algae Fucoxanthin Is Hydrolyzed to Fucoxanthinol during Absorption by Caco-2 Human Intestinal Cells and Mice. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 946–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hashimoto, T.; Ozaki, Y.; Taminato, M.; Das, S.K.; Mizuno, M.; Yoshimura, K.; Maoka, T.; Kanazawa, K. The distribution and accumulation of fucoxanthin and its metabolites after oral administration in mice. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 102, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yonekura, L.; Kobayashi, M.; Terasaki, M.; Nagao, A. Keto-Carotenoids Are the Major Metabolites of Dietary Lutein and Fucoxanthin in Mouse Tissues. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 1824–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asai, A.; Yonekura, L.; Nagao, A. Low bioavailability of dietary epoxyxanthophylls in humans. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 100, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Domínguez-González, M.R.; Herbello-Hermelo, P.; Vélez, D.; Devesa, V.; Bermejo-Barrera, P.; González, R.D.; Chiocchetti, G.M. Evaluation of iodine bioavailability in seaweed using in vitro methods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 8435–8442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combet, E.; Ma, Z.F.; Cousins, F.; Thompson, B.; Lean, M.E.J. Low-level seaweed supplementation improves iodine status in iodine-insufficient women. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Plaza, M.; Cifuentes, A.; Ibañez, E. In the search of new functional food ingredients from algae. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 19, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Functional Food | Functional Ingredient | Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fish cakes | F. vesiculosus extracts: 100% H2O, 80% EtOH | No off-flavours and lower rancid odour and flavour None of the extracts had influence on lipid oxidation nor quality of the products | [73] |

| Cod muscle and protein isolates | F. vesiculosus 80% EtOH extract and further fractions (EtOAc + Sephadex LH-20) | ↓ Lipid oxidation in both fish muscle and protein isolates 300 mg/kg of the oligomeric phlorotannin fractions exhibited an effect comparable to that of 100 mg/kg propyl gallate | [75] |

| Cod mince | EtOAc fraction of F. vesiculosus 80% EtOH extract | ↓ Lipid oxidation in fish muscle | [76] |

| Cod protein hydrolysates | EtOAc fraction of F. vesiculosus 80% EtOH extract | ↓ Lipid hydroperoxide and TBARS formation during protein hydrolyzation ↑ Antioxidant activity of the final protein hydrolysates | [78] |

| Cod protein hydrolysates | EtOAc fraction of F. vesiculosus 80% EtOH extract | ↓ Lipid oxidation during protein hydrolysates freeze drying ↑ Antioxidant activity of the final protein hydrolysates Improved sensorial aspects (bitter, soap, fish oil and rancidity taste) | [77] |

| Minced horse mackerel | F. vesiculosus antioxidant dietary fibre | ↓ Lipid oxidation during 5 months of storage at −20 °C ↓ Total dripping after thawing and cooking after up to 3 months of frozen storage Improved fish mince flavour | [74] |

| Granola bars enriched with fish oil emulsion | F. vesiculosus 100% H2O, 70% acetone and 80% EtOH extracts | ↓ Oxidation products after storage ↓ Iron-lipid interactions Acetone and EtOH extracts provided additional lipid oxidation protection ↑ Phenolic content, radical scavenging activity and interfacial affinity of phenolic compounds Possible tocopherol regeneration | [79] |

| Granola bars enriched with fish oil emulsion | F. vesiculosus 100% H2O, 70% acetone and 80% EtOH extracts | ↓ Lipid oxidation during storage ↑ Effectiveness for lower concentrations of EtOH and acetone extracts ↑ Phenolic content, radical scavenging activity and interfacial affinity of phenolic compounds Possible tocopherol regeneration | [80] |

| Fish-oil-enriched milk and mayonnaise | F. vesiculosus: EtOAc fraction from an 80% EtOH extract, 100% H2O | ↑ Lipid stability and ↓ oxidation of EPA and DHA and subsequent secondary degradation products in both foods—H2O extract at 2.0 g/100 g exerted higher inhibitory effects on mayonnaise’s peroxide formation. | [81] |

| Fish-oil-enriched mayonnaise | F. vesiculosus 100% H2O, 70% acetone, and 80% EtOH extracts | Dose-dependent inhibition of lipid oxidation exhibited by EtOH and acetone extracts H2O extract increased peroxide formation | [82] |

| Pork liver pâté | F. vesiculosus commercial extract | Decrease in lightness values after storage Redness and yellowness maintained after storage Protection against oxidation comparable to BHT samples ↓ Total volatile compounds | [83] |

| Pork patties | F. vesiculosus 50% EtOH extracts | ↓ TBARS slightly Did not improve colour, surface discoloration or odour attributes No significant differences between seaweed and control samples in sensory analysis | |

| Milk | F. vesiculosus 60% EtOH extracts | ↑ Milk lipid stability and shelf-life characteristics Appearance of greenish colour and fishy taste Overall sensory attributes were worsened | [84] |

| Yoghurts | F. vesiculosus 60% EtOH extracts | No influence on chemical and microbiological characteristics ↑ Yogurts lipid stability and shelf-life characteristics Overall sensory attributes were worsened | [85] |

| Pasteurized apple beverage | F. vesiculosus fucoidan extract | Dose-, time- and temperature-dependent bacteriostatic and bactericidal effects against L. monocytogenes and S. typhimurium S. typhimurium showed higher sensitivity to the extract | [86] |

| Bread | F. vesiculosus powder | ↑ Dough viscosity and wheat dough consistency ↓ Porosity ↑ Density, crumb firmness and green colour of crust 4% seaweed powder was considered optimal | [87] |

| Functional Food | Functional Ingredient | Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poultry steaks | 3% dry matter H. elongata | ↑ Purge loss slightly ↓ Cooking loss ↑ Levels of total viable counts, lactic acid bacteria, tyramine and spermidine No important changes observed during chilled storage Positive overall acceptance by a sensory panel | [90] |

| Pork gel/emulsion systems | 2.5% and 5% dry matter H. elongata | ↑ Water and fat binding properties ↑ Hardness and chewiness of cooked products ↓ Springiness and cohesiveness | [1] |

| Low-salt pork emulsion systems | 5.6% dry matter H. elongata | ↑ Content of n-3 PUFA ↓ n-6/n-3 PUFA ratio ↓ Thrombogenic index ↑ Concentrations of K, Ca, Mg and Mn | [91] |

| Pork meat batter | 3.4% powder H. elongata | ↑ Water/oil retention capacity, hardness and elastic modulus. Thermal denaturation of protein fraction was prevented by seaweed alginates Nutritional enhancement | [92] |

| Restructured meat | 5% powder H. elongata | Effects in rats: ↓ Total cholesterol ↑ CYP7A1, GPx, SOD, GR expression ↓ CAT expression | [93] |

| Restructured meat | 5% powder H. elongata | ↓ HSL and FAS and ↑ ACC (p < 0.05) expression on rats fed with seaweed fortified meat comparing with rats under hypercholesterolemic diet | [94] |

| Frankfurters | 3.3% H. elongata powder | ↑ Cooking loss ↓ Emulsion stability Combination of ingredients provided healthier meat products with lower fat and salt contents Worsened physicochemical and sensory characteristics | [95] |

| Beef patties | 10–40% (w/w) H. elongata | ↓ Cooking loss ↑ Tenderness, dietary fibre levels, TPC and antioxidant activity ↓ Microbiological counts and lipid oxidation Patties with 40% seaweed had the highest overall acceptability | [96] |

| Bread sticks | 2.93–17.07% H. elongata powder | Highest concentration had higher phycochemical constituents, acceptable edible texture and overall colour | [97] |

| Bread | 8% (w/w) H. elongata | ↑ TPC ↑ Antioxidant activity in DPPH•, ORAC and TEAC | [98] |

| Yoghurt and Quark | 0.25–1% dehydrated H. elongata | Alterations in all yoghurt attributes except for buttery odour, and acid and salty flavours Alterations in all quark attributes except yogurt odour, acid flavour and sweet flavour. Sensory characteristics worsened | [99] |

| Functional Food | Functional Ingredient | Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beef patties | 3% dry matter U. pinnatifida | ↑ Binding properties and cooking retention values of, fat, fatty acids and ash Replacement of animal fat with olive-in-water emulsion and/or seaweed was reportedly healthier. ↓ Thawing and↑ softer texture Changes on the microstructure due to formation of alginate chains Overall acceptable products and fit for consumption | [104,105] |

| Chicken breast | 200 mg/kg U. pinnatifida | ↑ Redness and yellowness ↓ Lipid oxidation in chilling storage and after cooking Overall appearance and shelf-life were enhanced | [106] |

| Pork gel/emulsion systems | 2.5% and 5% dry matter U. pinnatifida | ↑ Water and fat binding properties ↑ Hardness and chewiness of cooked products ↓ Springiness and cohesiveness | [1] |

| Low-salt pork emulsion systems | 5.6% dry matter U. pinnatifida | ↑ Content of n-3 PUFA ↓ n-6/n-3 PUFA ratio ↑ Concentrations of K, Ca, Mg and Mn ↑ Antioxidant capacity | [91] |

| Pasta | 100:0, 95:5, 90:10, 80:20 and 70:30 (semolina/U. pinnatifida; w/w) | 10% U. pinnatifida was the most acceptable ↑ Amino acid, fatty acid profile and nutritional value of the product Fucoxanthin was not affected by pasta making and cooking step | [107] |

| Yoghurt and Quark | 0.25–1% dehydrated U. pinnatifida | ↑ Seaweed flavour with ↓ flavour quality for 0.5% seaweed Alterations in all yoghurt attributes except for buttery odour, and acid and salty flavours Alterations in all quark attributes except yogurt odour, and acid and sweet flavours. Sensory characteristics worsened | [99] |

| Bread | 8% (w:w) U. pinnatifida:wheat flour | ↑ TPC, ↑ Antioxidant activity in DPPH•, ORAC and TEAC | [98] |

| Functional Food | Functional Ingredient | Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pork | 20 g A. nodosum /kg feed | ↑ I content in piglet’s muscles and internal organs | [110] |

| Pork liver paté | A. nodosum extract at 500 mg/kg | ↑ Protein content ↑ Redness and yellowness after storage Degree of protection against oxidation comparable to BHT samples ↓ Total volatile compounds | [83] |

| Milk | A. nodosum (100% H2O and 80% EtOH) extracts (0.25 and 0.5 (w/w)) | ↓ TBARS formation ↑ Radical scavenging and ferrous-ion-chelating activities before and after digestion Supplementation on Caco-2 cells did not affect cellular antioxidant status EtOH extracts had greenish colour and overall sensory attributes were worsened | [84] |

| Yoghurts | A. nodosum (100% H2O and 80% EtOH) extracts (0.25 and 0.5 (w/w)) | No influence on chemical characteristics Yoghurts had antioxidant activity before and after digestion Supplementation on Caco-2 cells did not affect cellular antioxidant status Overall sensory attributes were worsened | [85] |

| Bread | 1–4% A. nodosum per 400 g loaf | All samples sensorially accepted ↓ Energy intake after 4 h Glucose and cholesterol blood levels not affected | [111] |

| Functional Food | Functional Ingredient | Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chars | Laminaria digitata (0.8% in fish meal) | ↑ 4 times the I content in fish muscle | [113] |

| Gilthead seabream | Laminaria digitata (10% in fish meal) | ↑ I content in fish fillets | [114] |

| Rainbow trout | Laminaria digitata (0.65% in fish meal) | ↑ I content in fish fillets | [115] |

| Pork | Laminaria digitata (1.16 and 1.86 g/kg feed) | ↑ I content in pigs’ muscles by 45% and internal organs by 213% | [116] |

| Pork | Laminaria digitata (5.32 kg/t feed) | ↑ Antioxidant activity ↓ Lipid oxidations ↓ Microbial counts | [117] |

| Pork patties | 0.01%, 0.1% and 0.5% (w/w) of 9.3% laminarin and 7.8% fucoidan from L. digitata | ↑ Lipid antioxidant activity for L/F extract (0.5%) No effect in colour, lipid oxidation, texture or sensorial acceptance when adding L/F extract | [118] |

| Pork homogenates | 3 and 6 mg/mL of laminaran, fucoidan and both from L. digitata | L had no antioxidant activity The L/F extract had higher antioxidant activity than F, after cooking and post digestion of minced pork. DPPH• antioxidant activity lower in Caco-2 cell model with L/F extracts Seaweed extracts containing F had higher antioxidant activity of the functional cooked meat products. | [42] |

| Sausages | 1–4% L. japonica powder | No changes in moisture, protein, and fat contents ↓ Lightness and redness values ↓ Cooking loss ↑ Emulsion stability, hardness, gumminess, and chewiness 1% seaweed had highest overall acceptability | [119] |

| Pork/chicken patties | Laminaria japonica (replacement od 2.25 g of pork/chicken for an equal amount of seaweed) | ↓ Increased in postprandial glucose blood levels; ↓ TC and LDL-C | [120] |

| Yoghurt | Laminaria spp. (0.2% or 0.5% w/w) | ↑ I, Ca, K, Na, Mg, and Fe | [121] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Afonso, N.C.; Catarino, M.D.; Silva, A.M.S.; Cardoso, S.M. Brown Macroalgae as Valuable Food Ingredients. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 365. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/antiox8090365

Afonso NC, Catarino MD, Silva AMS, Cardoso SM. Brown Macroalgae as Valuable Food Ingredients. Antioxidants. 2019; 8(9):365. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/antiox8090365

Chicago/Turabian StyleAfonso, Nuno C., Marcelo D. Catarino, Artur M. S. Silva, and Susana M. Cardoso. 2019. "Brown Macroalgae as Valuable Food Ingredients" Antioxidants 8, no. 9: 365. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/antiox8090365