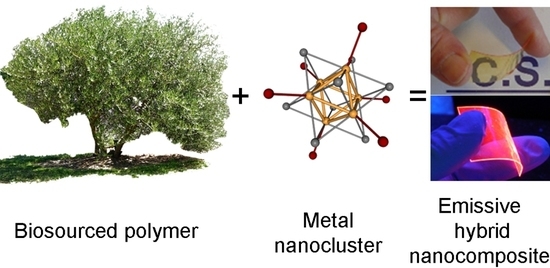

Flexible and Transparent Luminescent Cellulose-Transition Metal Cluster Composites

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wibowo, A.C.; Misra, M.; Park, H.-M.; Drzal, L.T.; Schalek, R.; Mohanty, A.K. Biodegradable nanocomposites from cellulose acetate: Mechanical, morphological, and thermal properties. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2006, 37, 1428–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, E.S.; Cui, Z.; Anastas, P.T. Green Chemistry: A design framework for sustainability. Energy Environ. Sci. 2009, 2, 1038–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattori, V.; Melucci, M.; Ferrante, L.; Zambianchi, M.; Manet, I.; Oberhauser, W.; Giambastiani, G.; Frediani, M.; Giachi, G.; Camaioni, N. Poly(lactic acid) as a transparent matrix for luminescent solar concentrators: A renewable material for a renewable energy technology. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 2849–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaurav, A.; Ashamol, A.; Deepthi, M.V.; Sailaja, R.R.N. Biodegradable nanocomposites of cellulose acetate phthalate and chitosan reinforced with functionalized nanoclay: Mechanical, thermal, and biodegradability studies. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012, 125, E16–E26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargarzadeh, H.; Ahmad, I.; Thomas, S.; Dufresne, A. (Eds.) Handbook of Nanocellulose and Cellulose Nanocomposites; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2017; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Nogi, M.; Yano, H. Transparent Nanocomposites Based on Cellulose Produced by Bacteria Offer Potential Innovation in the Electronics Device Industry. Adv. Mater. 2008, 20, 1849–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okahisa, Y.; Yoshida, A.; Miyaguchi, S.; Yano, H. Optically transparent wood–cellulose nanocomposite as a base substrate for flexible organic light-emitting diode displays. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2009, 69, 1958–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaru, N.; Olaru, L.; Tudorachi, N.; Dunca, S.; Pintilie, M. Nanostructures of Cellulose Acetate Phthalate Obtained by Electrospinning from 2-Methoxyethanol-Containing Solvent Systems: Morphological Aspects, Thermal Behavior, and Antimicrobial Activity. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 696–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Fang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Dai, J.; Yao, Y.; Shen, F.; Preston, C.; Wu, W.; Peng, P.; Jang, N.; et al. Extreme Light Management in Mesoporous Wood Cellulose Paper for Optoelectronics. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 1369–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, F.I.; Dick, C.; Meng, L.; Mahpeykar, S.M.; Ahvazi, B.; Wang, X. Cellulose nanocrystals as host matrix and waveguide materials for recyclable luminescent solar concentrators. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 32436–32441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muthamma, K.; Sunil, D. Cellulose as an Eco-Friendly and Sustainable Material for Optical Anticounterfeiting Applications: An Up-to-Date Appraisal. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 42681–42699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, R.R.; Esmerian, O.K. Effect of Plasticizers on Some Physical Properties of Cellulose Acetate Phthalate Films. J. Pharm. Sci. 1971, 60, 312–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.; Liu, Z.-W.; Lu, J.; Liu, Z.-T. Cellulose Triacetate Optical Film Preparation from Ramie Fiber. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 6212–6215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, B.; Jiang, G.Y.; Zhou, J.H.; Zhu, Y.; Cheng, W.K.; Zhao, D.W.; Wang, K.J.; Xu, G.W.; Yu, H.P. Molecular-Scale Design of Cellulose-Based Functional Materials for Flexible Electronic Devices. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2021, 7, 2000944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.W.; Zhu, Y.; Cheng, W.K.; Chen, W.S.; Wu, Y.Q.; Yu, H.P. Cellulose-Based Flexible Functional Materials for Emerging Intelligent Electronics. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2000619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Wang, Q. Luminescent Cu2+ Probes Based on Rare-Earth (Eu3+ and Tb3+) Emissive Transparent Cellulose Hydrogels. J. Fluoresc. 2012, 22, 1581–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skwierczyńska, M.; Runowski, M.; Goderski, S.; Szczytko, J.; Rybusiński, J.; Kulpiński, P.; Lis, S. Luminescent–Magnetic Cellulose Fibers, Modified with Lanthanide-Doped Core/Shell Nanostructures. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 10383–10390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Shi, Z.; Wang, J.; Xiong, C.; Saito, T.; Isogai, A. Luminescent and Transparent Nanocellulose Films Containing Europium Carboxylate Groups as Flexible Dielectric Materials. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2018, 1, 4972–4979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattab, T.A.; El-Naggar, M.E.; Abdelrahman, M.S.; Aldalbahi, A.; Hatshan, M.R. Facile development of photochromic cellulose acetate transparent nanocomposite film immobilized with lanthanide-doped pigment: Ultraviolet blocking, superhydrophobic, and antimicrobial activity. Luminescence 2021, 36, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abitbol, T.; Gray, D. CdSe/ZnS QDs Embedded in Cellulose Triacetate Films with Hydrophilic Surfaces. Chem. Mater. 2007, 19, 4270–4276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zou, H.; Liu, M.; Zhang, K.; Sheng, Y.; Cui, J.; Zhang, H.; Yang, B. Surface Ligand Dynamics-Guided Preparation of Quantum Dots–Cellulose Composites for Light-Emitting Diodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 15830–15839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Tu, K.; Goldhahn, C.; Keplinger, T.; Adobes-Vidal, M.; Sorieul, M.; Burgert, I. Luminescent and Hydrophobic Wood Films as Optical Lighting Materials. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 13775–13783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Shao, Z.; Chen, B.; Zhang, T.; Wang, F.; Zhong, H. Transparent, flexible and luminescent composite films by incorporating CuInS2 based quantum dots into a cyanoethyl cellulose matrix. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 2675–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, B.; Ji, Y.; Wang, L. Luminescent and UV-Shielding ZnO Quantum Dots/Carboxymethylcellulose Sodium Nanocomposite Polymer Films. Polymers 2018, 10, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cotton, F.A. Metal Atom Clusters in Oxide Systems. Inorg. Chem. 1964, 3, 1217–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costuas, K.; Garreau, A.; Bulou, A.; Fontaine, B.; Cuny, J.; Gautier, R.; Mortier, M.; Molard, Y.; Duvail, J.L.; Faulques, E.; et al. Combined theoretical and time-resolved photoluminescence investigations of [Mo6Bri8Bra6]2− metal cluster units: Evidence of dual emission. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 28574–28585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dierre, B.; Costuas, K.; Dumait, N.; Paofai, S.; Amela-Cortes, M.; Molard, Y.; Grasset, F.; Cho, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Ohashi, N.; et al. Mo6 cluster-based compounds for energy conversion applications: Comparative study of photoluminescence and cathodoluminescence. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2017, 18, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khlifi, S.; Taupier, G.; Amela-Cortes, M.; Dumait, N.; Freslon, S.; Cordier, S.; Molard, Y. Expanding the Toolbox of Octahedral Molybdenum Clusters and Nanocomposites Made Thereof: Evidence of Two-Photon Absorption Induced NIR Emission and Singlet Oxygen Production. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 5446–5451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirakci, K.; Kubát, P.; Dušek, M.; Fejfarová, K.; Šícha, V.; Mosinger, J.; Lang, K. A Highly Luminescent Hexanuclear Molybdenum Cluster—A Promising Candidate toward Photoactive Materials. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 2012, 3107–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirakci, K.; Kubát, P.; Langmaier, J.; Polívka, T.; Fuciman, M.; Fejfarová, K.; Lang, K. A comparative study of the redox and excited state properties of (nBu4N)2[Mo6X14] and (nBu4N)2[Mo6X8(CF3COO)6] (X = Cl, Br, or I). Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 7224–7232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolov, M.N.; Mihailov, M.A.; Peresypkina, E.V.; Brylev, K.A.; Kitamura, N.; Fedin, V.P. Highly luminescent complexes [Mo6X8(n-C3F7COO)6]2− (X = Br, I). Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 6375–6377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akagi, S.; Fujii, S.; Kitamura, N. A study on the redox, spectroscopic, and photophysical characteristics of a series of octahedral hexamolybdenum(ii) clusters: [{Mo6X8}Y6]2− (X, Y = Cl, Br, or I). Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 1131–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khlifi, S.; Le Ray, N.F.; Paofai, S.; Amela-Cortes, M.; Akdas-Kilic, H.; Taupier, G.; Derien, S.; Cordier, S.; Achard, M.; Molard, Y. Self-erasable inkless imprinting using a dual emitting hybrid organic-inorganic material. Mater. Today 2020, 35, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lunt, R.R. Transparent Luminescent Solar Concentrators for Large-Area Solar Windows Enabled by Massive Stokes-Shift Nanocluster Phosphors. Adv. Energy Mater. 2013, 3, 1143–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huby, N.; Bigeon, J.; Lagneaux, Q.; Amela-Cortes, M.; Garreau, A.; Molard, Y.; Fade, J.; Desert, A.; Faulques, E.; Bêche, B.; et al. Facile design of red-emitting waveguides using hybrid nanocomposites made of inorganic clusters dispersed in SU8 photoresist host. Opt. Mater. 2016, 52, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlifi, S.; Bigeon, J.; Amela-Cortes, M.; Dumait, N.; Akdas-Kiliç, H.; Taupier, G.; Freslon, S.; Cordier, S.; Derien, S.; Achard, M.; et al. Poly(dimethylsiloxane) functionalized with complementary organic and inorganic emitters for the design of white emissive waveguides. J. Mater. Chem. C Mater. Opt. Electron. Devices 2021, 9, 7094–70102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roxin, P.; Karlsson, A.; Singh, S.K. Characterization of Cellulose Acetate Phthalate (CAP). Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 1998, 24, 1025–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, M.; Kuai, W.; Amela-Cortes, M.; Cordier, S.; Molard, Y.; Mohammed-Brahim, T.; Jacques, E.; Harnois, M. Epoxy Based Ink as Versatile Material for Inkjet-Printed Devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 21975–21984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amela-Cortes, M.; Garreau, A.; Cordier, S.; Faulques, E.; Duvail, J.-L.; Molard, Y. Deep red luminescent hybrid copolymer materials with high transition metal cluster content. J. Mater. Chem. C 2014, 2, 1545–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amela-Cortes, M.; Molard, Y.; Paofai, S.; Desert, A.; Duvail, J.-L.; Naumov, N.G.; Cordier, S. Versatility of the ionic assembling method to design highly luminescent PMMA nanocomposites containing [M6Qi8La6]n− octahedral nano-building blocks. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorotnikova, N.A.; Alekseev, A.Y.; Vorotnikov, Y.A.; Evtushok, D.V.; Molard, Y.; Amela-Cortes, M.; Cordier, S.; Smolentsev, A.I.; Burton, C.G.; Kozhin, P.M.; et al. Octahedral molybdenum cluster as a photoactive antimicrobial additive to a fluoroplastic. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 105, 110150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirakci, K.; Zelenka, J.; Rumlová, M.; Martinčík, J.; Nikl, M.; Ruml, T.; Lang, K. Octahedral molybdenum clusters as radiosensitizers for X-ray induced photodynamic therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2018, 6, 4301–4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandhonneur, N.; Hatahet, T.; Amela-Cortes, M.; Molard, Y.; Cordier, S.; Dollo, G. Molybdenum cluster loaded PLGA nanoparticles: An innovative theranostic approach for the treatment of ovarian cancer. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2018, 125, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirakci, K.; Pozmogova, T.N.; Protasevich, A.Y.; Vavilov, G.D.; Stass, D.V.; Shestopalov, M.A.; Lang, K. A water-soluble octahedral molybdenum cluster complex as a potential agent for X-ray induced photodynamic therapy. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 2893–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandhonneur, N.; Boucaud, Y.; Verger, A.; Dumait, N.; Molard, Y.; Cordier, S.; Dollo, G. Molybdenum cluster loaded PLGA nanoparticles as efficient tools against epithelial ovarian cancer. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 592, 120079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verger, A.; Dollo, G.; Martinais, S.; Molard, Y.; Cordier, S.; Amela-Cortes, M.; Brandhonneur, N. Molybdenum-Iodine Cluster Loaded Polymeric Nanoparticles Allowing a Coupled Therapeutic Action with Low Side Toxicity for Treatment of Ovarian Cancer. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 111, 3377–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.A.; Turro, C.; Newsham, M.D.; Nocera, D.G. Oxygen quenching of electronically excited hexanuclear molybdenum and tungsten halide clusters. J. Phys. Chem. 1990, 94, 4500–4507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.A.; Newsham, M.D.; Worsham, C.; Nocera, D.G. Efficient Singlet Oxygen Generation from Polymers Derivatized with Hexanuclear Molybdenum Clusters. Chem. Mater. 1996, 8, 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, R.N.; Baker, G.L.; Ruud, C.; Nocera, D.G. Fiber-optic oxygen sensor using molybdenum chloride cluster luminescence. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1999, 75, 2885–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amela-Cortes, M.; Paofai, S.; Cordier, S.; Folliot, H.; Molard, Y. Tuned red NIR phosphorescence of polyurethane hybrid composites embedding metallic nanoclusters for oxygen sensing. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 8177–8180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowder, G.A. Infrared spectra of pentafluoropropionate esters. J. Fluor. Chem. 1973, 2, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakellariou, P.; Rowe, R.C.; White, E.F.T. The thermomechanical properties and glass transition temperatures of some cellulose derivatives used in film coating. Int. J. Pharm. 1985, 27, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayalakshmi Rao, R.; Ashokan, P.V.; Shridhar, M.H. Study of cellulose acetate hydrogen phthalate(CAP)-poly methyl methacrylate (PMMA) blends by thermogravimetric analysis. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2000, 70, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.K.; Amela-Cortes, M.; Roiland, C.; Cordier, S.; Molard, Y. From metallic cluster-based ceramics to nematic hybrid liquid crystals: A double supramolecular approach. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 3774–3777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guy, K.; Ehni, P.; Paofai, S.; Forschner, R.; Roiland, C.; Amela-Cortes, M.; Cordier, S.; Laschat, S.; Molard, Y. Lord of The Crowns: A New Precious in the Kingdom of Clustomesogens. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 11692–11696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evtushok, D.V.; Melnikov, A.R.; Vorotnikova, N.A.; Vorotnikov, Y.A.; Ryadun, A.A.; Kuratieva, N.V.; Kozyr, K.V.; Obedinskaya, N.R.; Kretov, E.I.; Novozhilov, I.N.; et al. A comparative study of optical properties and X-ray induced luminescence of octahedral molybdenum and tungsten cluster complexes. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 11738–11747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robin, M.; Dumait, N.; Amela-Cortes, M.; Roiland, C.; Harnois, M.; Jacques, E.; Folliot, H.; Molard, Y. Direct Integration of Red-NIR Emissive Ceramic-like AnM6Xi8Xa6 Metal Cluster Salts in Organic Copolymers Using Supramolecular Interactions. Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 4825–4829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prévôt, M.; Amela-Cortes, M.; Manna, S.K.; Lefort, R.; Cordier, S.; Folliot, H.; Dupont, L.; Molard, Y. Design and Integration in Electro-Optic Devices of Highly Efficient and Robust Red-NIR Phosphorescent Nematic Hybrid Liquid Crystals Containing [Mo6I8(OCOCnF2n+1)6]2− (n = 1, 2, 3) Nanoclusters. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25, 4966–4975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Kanda, T.; Nishihara, Y.; Ooshima, T.; Saito, Y. Correlation study among oxygen permeability, molecular mobility, and amorphous structure change of poly(ethylene-vinylalcohol copolymers) by moisture. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2009, 47, 1181–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvinov, V.M.; Persyn, O.; Miri, V.; Lefebvre, J.M. Morphology, Phase Composition, and Molecular Mobility in Polyamide Films in Relation to Oxygen Permeability. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 7668–7679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | MC (wt%) | Td (°C) | Residue 400 °C (wt%) | Calculated MC Residue (wt%) | Tg (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAP | 0 | 374 | 12 | 0 | 157 |

| MoIP1@CAP | 1 | 324 | 14 | 2 | 153 |

| MoIP10@CAP | 10 | 310 | 22 | 10 | 153 |

| MoIP20@CAP | 20 | 305 | 30 | 18 | 141 |

| MoIP30@CAP | 30 | 297 | 36 | 24 | 141 |

| Sample | Φem a | λmax/nm | FWHM/cm−1 | τ d/μs (%) | τav e | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| air | N2 | |||||

| MoIP | 0.35 | - | 650 | 1920 | 5 (28) 50 (72) | 48 |

| MoIP1@CAP | 29 b/45 c | 34 b/47 c | 653 | 2180 | 113 | 113 |

| MoIP10@CAP | 24 b/34 c | 32 b/40 c | 658 | 2128 | 113 | 113 |

| MoIP20@CAP | 23 b/19 c | 32 b/27 c | 650 | 2128 | 144 (41) 99 (59) | 122 |

| MoIP30@CAP | 35 b/27 c | 42 b/36 c | 657 | 2156 | 123 (66) 67 (33) | 111 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amela-Cortes, M.; Dumait, N.; Artzner, F.; Cordier, S.; Molard, Y. Flexible and Transparent Luminescent Cellulose-Transition Metal Cluster Composites. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 580. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/nano13030580

Amela-Cortes M, Dumait N, Artzner F, Cordier S, Molard Y. Flexible and Transparent Luminescent Cellulose-Transition Metal Cluster Composites. Nanomaterials. 2023; 13(3):580. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/nano13030580

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmela-Cortes, Maria, Noée Dumait, Franck Artzner, Stéphane Cordier, and Yann Molard. 2023. "Flexible and Transparent Luminescent Cellulose-Transition Metal Cluster Composites" Nanomaterials 13, no. 3: 580. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/nano13030580