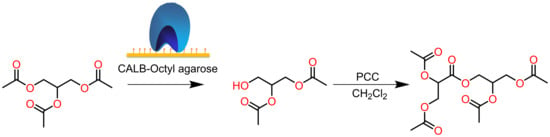

Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of the New 3-((2,3-Diacetoxypropanoyl)oxy)propane-1,2-diyl Diacetate Using Immobilized Lipase B from Candida antarctica and Pyridinium Chlorochromate as an Oxidizing Agent

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Immobilization of CALB on Octyl-agarose

2.2. Hydrolysis of Triacetin (1) Catalyzed by CALB-OC

2.3. 1,2-Diacetin (2) Oxidation with PCC

2.4. Biological Activity of 3-((2,3-Diacetoxypropanoyl)oxy)propane-1,2-diyl diacetate (5)

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Standard Activity Determination

3.2. Immobilization of CALB on Octyl agarose beads

3.3. Triacetin (1) Hydrolysis with CALB-OC

3.4. Synthesis of 3-((2,3-Diacetoxypropanoyl)oxy)propane-1,2-diyl diacetate (5)

3.5. Biological Activity of 3-((2,3-Diacetoxypropanoyl)oxy)propane-1,2-diyl diacetate (5)

3.5.1. Antibacterial Activity

3.5.2. Antifungal Activity

3.5.3. Hemolytic Activity

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CALB | Candida antarctica |

| CALB-OC | Candida antarctica immobilized on octyl-agarose |

| PCC | pyridinium chlorochromate |

| IR | infrared spectroscopy |

| NMR | nuclear magnetic resonance |

| MS | mass spectrometry |

| HR | high resolution |

| PGs | polyglycerols |

| PGEs | polyglycerol esters |

| MIC50 | minimal inhibitory concentration |

| MRSA | methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

References

- Atadashi, I.M.; Aroua, M.K.; Abdul Aziz, A.R.; Sulaiman, N.M.N. The effects of catalysts in biodiesel production: A review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2013, 19, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semwal, S.; Arora, A.K.; Badoni, R.P.; Tuli, D.K. Biodiesel production using heterogeneous catalysts. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 2151–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Qi, F.; Yuan, C.; Du, W.; Liu, D. Lipase-catalyzed process for biodiesel production: Enzyme immobilization, process simulation and optimization. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 44, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaf, I.S.A.; Embong, N.H.; Khazaai, S.N.M.; Rahim, M.H.A.; Yusoff, M.M.; Lee, K.T.; Maniam, G.P. A review for key challenges of the development of biodiesel industry. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 185, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendiara, T.; García-Labiano, F.; Abad, A.; Gayán, P.; de Diego, L.F.; Izquierdo, M.T.; Adánez, J. Negative CO2 emissions through the use of biofuels in chemical looping technology: A review. Appl. Energy 2018, 232, 657–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivek, N.; Sindhu, R.; Madhavan, A.; Anju, A.J.; Castro, E.; Faraco, V.; Pandey, A.; Binod, P. Recent advances in the production of value added chemicals and lipids utilizing biodiesel industry generated crude glycerol as a substrate—Metabolic aspects, challenges and possibilities: An overview. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 239, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Ge, X.; Cui, S.; Li, Y. Value-added processing of crude glycerol into chemicals and polymers. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 215, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yang, F.; Hanna, M.A.; Sun, R. Value-added uses for crude glycerol--a byproduct of biodiesel production. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2012, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Talebian-Kiakalaieh, A.; Amin, N.A.S.; Rajaei, K.; Tarighi, S. Oxidation of bio-renewable glycerol to value-added chemicals through catalytic and electro-chemical processes. Appl. Energy 2018, 230, 1347–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Nordblad, M.; Nielsen, P.M.; Brask, J.; Woodley, J.M. In situ visualization and effect of glycerol in lipase-catalyzed ethanolysis of rapeseed oil. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2011, 72, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, J.; Xu, X.; Mu, H. Diacylglycerol synthesis by enzymatic glycerolysis: Screening of commercially available lipases. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2005, 82, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, D.A.; Tonetto, G.M.; Ferreira, M.L. Valorization of glycerol through the enzymatic synthesis of acylglycerides with high nutritional value. Catalysts 2020, 10, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zheng, Y.; Chen, X.; Shen, Y. Erratum: Commodity chemicals derived from glycerol, an important biorefinery feedstock (Chemical Reviews (2008) 108 (5253)). Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferretti, C.A.; Soldano, A.; Apesteguía, C.R.; Di Cosimo, J.I. Monoglyceride synthesis by glycerolysis of methyl oleate on solid acid-base catalysts. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 161, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rarokar, N.R.; Menghani, S.; Kerzare, D.; Khedekar, P.B. Progress in Synthesis of Monoglycerides for Use in Food and Pharmaceuticals. J. Exp. Food Chem. 2017, 03, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.; Yang, B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Ning, Z.; Li, L. Enzymatic Production of Monoacylglycerols with Camellia Oil by the Glycerolysis Reaction. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2010, 87, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santaniello, E.; Casati, S.; Ciuffreda, P. Lipase-Catalyzed Deacylation by Alcoholysis: A Selective, Useful Transesterification Reaction. Curr. Org. Chem. 2006, 10, 1095–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonntag, N.O.V. Glycerolysis of fats and methyl esters—Status, review and critique. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1982, 59, 795A–802A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, B.G.; Boyer, V. Biocatalysis and enzymes in organic synthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2001, 18, 618–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotor-Fernández, V.; Vicente, G. Use of Lipases in Organic Synthesis. In Industrial Enzymes: Structure, Function and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 301–315. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E.M.; Larsson, K.M.; Kirk, O. One Biocatalyst–Many Applications: The Use of Candida Antarctica B-Lipase in Organic Synthesis. Biocatal. Biotransformation 1998, 16, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manova, D.; Gallier, F.; Tak-Tak, L.; Yotava, L.; Lubin-Germain, N. Lipase-catalyzed amidation of carboxylic acid and amines. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59, 2086–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Vidal, T.; Armenta-Perez, V.P.; Rosales-Rivera, L.C.; Mateos-Díaz, J.C.; Rodríguez, J.A. Cross-linked enzyme aggregates of recombinant Candida antarctica lipase B for the efficient synthesis of olvanil, a nonpungent capsaicin analogue. Biotechnol. Prog. 2019, 35, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stergiou, P.-Y.; Foukis, A.; Filippou, M.; Koukouritaki, M.; Parapouli, M.; Theodorou, L.G.; Hatziloukas, E.; Afendra, A.; Pandey, A.; Papamichael, E.M. Advances in lipase-catalyzed esterification reactions. Biotechnol. Adv. 2013, 31, 1846–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanem, A.; Aboul-Enein, H.Y. Application of lipases in kinetic resolution of racemates. Chirality 2005, 17, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, P. Controlling lipase enantioselectivity for organic synthesis. Biomol. Eng. 2001, 18, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Dhar, K.; Kanwar, S.S.; Arora, P.K. Lipase catalysis in organic solvents: Advantages and applications. Biol. Proced. Online 2016, 18, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adlercreutz, P. Immobilisation and application of lipases in organic media. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 6406–6436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Verger, R. ‘Interfacial activation’ of lipases: Facts and artifacts. Trends Biotechnol. 1997, 15, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, R.D.; Verger, R. Lipases: Interfacial Enzymes with Attractive Applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1998, 37, 1608–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zisis, T.; Freddolino, P.L.; Turunen, P.; van Teeseling, M.C.F.; Rowan, A.E.; Blank, K.G. Interfacial Activation of Candida antarctica Lipase B: Combined Evidence from Experiment and Simulation. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 5969–5979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manoel, E.A.; dos Santos, J.C.S.; Freire, D.M.G.; Rueda, N.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Immobilization of lipases on hydrophobic supports involves the open form of the enzyme. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2015, 71, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stauch, B.; Fisher, S.J.; Cianci, M. Open and closed states of Candida antarctica lipase B: Protonation and the mechanism of interfacial activation. J. Lipid Res. 2015, 56, 2348–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bastida, A.; Sabuquillo, P.; Armisen, P.; Fernández-Lafuente, R.; Huguet, J.; Guisán, J.M. A single step purification, immobilization, and hyperactivation of lipases via interfacial adsorption on strongly hydrophobic supports. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1998, 58, 486–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Armisén, P.; Sabuquillo, P.; Fernández-Lorente, G.; Guisán, J.M. Immobilization of lipases by selective adsorption on hydrophobic supports. Chem. Phys. Lipids 1998, 93, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.C.; Virgen-Ortíz, J.J.; dos Santos, J.C.S.; Berenguer-Murcia, Á.; Alcantara, A.R.; Barbosa, O.; Ortiz, C.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Immobilization of lipases on hydrophobic supports: Immobilization mechanism, advantages, problems, and solutions. Biotechnol. Adv. 2019, 37, 746–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ortiz, C.; Ferreira, M.L.; Barbosa, O.; dos Santos, J.C.S.; Rodrigues, R.C.; Berenguer-Murcia, Á.; Briand, L.E.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Novozym 435: The “perfect” lipase immobilized biocatalyst? Catal. Sci. Technol. 2019, 9, 2380–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, L.; Li, X.; Chen, P.; Hou, Z. Selective oxidation of glycerol in a base-free aqueous solution: A short review. Chinese J. Catal. 2019, 40, 1020–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, N.; Abdullah, A.Z. Production of lactic acid from glycerol via chemical conversion using solid catalyst: A review. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2017, 543, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habe, H.; Fukuoka, T.; Kitamoto, D.; Sakaki, K. Biotechnological production of d-glyceric acid and its application. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 84, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Roz, A.; Fongarland, P.; Dumeignil, F.; Capron, M. Glycerol to glyceraldehyde oxidation reaction over Pt-based catalysts under base-free conditions. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dodekatos, G.; Schünemann, S.; Tüysüz, H. Recent Advances in Thermo-, Photo-, and Electrocatalytic Glycerol Oxidation. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 6301–6333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katryniok, B.; Kimura, H.; Skrzyńska, E.; Girardon, J.S.; Fongarland, P.; Capron, M.; Ducoulombier, R.; Mimura, N.; Paul, S.; Dumeignil, F. Selective catalytic oxidation of glycerol: Perspectives for high value chemicals. Green Chem. 2011, 13, 1960–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzyńska, E.; Ftouni, J.; Mamede, A.-S.; Addad, A.; Trentesaux, M.; Girardon, J.-S.; Capron, M.; Dumeignil, F. Glycerol oxidation over gold supported catalysts—“Two faces” of sulphur based anchoring agent. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2014, 382, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.C.; Hess, W.W. Aldehydes from Primary Alcohols by Oxidation with Chromium Trioxide: Heptanal. Org. Synth. 2003, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Corey, E.J.; Suggs, J.W. Pyridinium chlorochromate. An efficient reagent for oxidation of primary and secondary alcohols to carbonyl compounds. Tetrahedron Lett. 1975, 16, 2647–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corey, E.J.; Schmidt, G. Useful procedures for the oxidation of alcohols involving pyridinium dichromate in approtic media. Tetrahedron Lett. 1979, 20, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katre, S.D. Applications of Chromium ( VI ) Complexes as Oxidants in Organic Synthesis: A Brief Review. Der Pharma Chemica 2018, 10, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, S.; Mishra, B.K. Chromium(VI) oxidants having quaternary ammonium ions: Studies on synthetic applications and oxidation kinetics. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 4367–4406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaiah, M.V.; Robles-Manuel, S.; Valange, S.; Barrault, J. Recent developments in acid and base-catalyzed etherification of glycerol to polyglycerols. Catal. Today 2012, 198, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.; Richter, M. Oligomerization of glycerol—A critical review. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2011, 113, 100–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehpour, S.; Dubé, M.A. Towards the Sustainable Production of Higher-Molecular-Weight Polyglycerol. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2011, 212, 1284–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, M.; Quadir, M.A.; Sharma, S.K.; Haag, R. Dendritic polyglycerols for biomedical applications. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 190–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Q.; Li, X.; Dong, J. Selective Synthesis of Diglycerol Monoacetals via Catalyst-Transfer in Biphasic System and Assessment of their Surfactant Properties. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 16813–16818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clacens, J.-M.; Pouilloux, Y.; Barrault, J. Selective etherification of glycerol to polyglycerols over impregnated basic MCM-41 type mesoporous catalysts. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2002, 227, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimazaki, A.; Sakamoto, J.J.; Furuta, M.; Tsuchido, T. Antifungal Activity of Diglycerin Ester of Fatty Acids against Yeasts and Its Comparison with Those of Sucrose Monopalmitate and Sodium Benzoate. Biocontrol Sci. 2016, 21, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, R.; Galy, N.; Singh, A.; Paulus, F.; Stöbener, D.; Schlesener, C.; Sharma, S.; Haag, R.; Len, C. A Simple and Efficient Process for Large Scale Glycerol Oligomerization by Microwave Irradiation. Catalysts 2017, 7, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansy, D.; Bosowska, K.; Czaja, K.; Poliwoda, A. The Formation of Glycerol Oligomers with Two New Types of End Groups in the Presence of a Homogeneous Alkaline Catalyst. Polymers (Basel) 2019, 11, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ayoub, M.; Abdullah, A.Z.; Ahmad, M.; Sultana, S. Performance of lithium modified zeolite Y catalyst in solvent-free conversion of glycerol to polyglycerols. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 2014, 8, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gholami, Z.; Abdullah, A.Z.; Lee, K.T. Catalytic Etherification of Glycerol to Diglycerol Over Heterogeneous Calcium-Based Mixed-Oxide Catalyst: Reusability and Stability. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2014, 202, 1397–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudrant, J.; Woodley, J.M.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Parameters necessary to define an immobilized enzyme preparation. Process. Biochem. 2020, 90, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.; Galvis, M.; Barbosa, O.; Ortiz, C.; Torres, R.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Solid-phase modification with succinic polyethyleneglycol of aminated lipase B from Candida antarctica: Effect of the immobilization protocol on enzyme catalytic properties. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2013, 87, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, O.; Ruiz, M.; Ortiz, C.; Fernández, M.; Torres, R.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Modulation of the properties of immobilized CALB by chemical modification with 2,3,4-trinitrobenzenesulfonate or ethylendiamine. Advantages of using adsorbed lipases on hydrophobic supports. Process. Biochem. 2012, 47, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trodler, P.; Pleiss, J. Modeling structure and flexibility of Candida antarctica lipase B in organic solvents. BMC Struct. Biol. 2008, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Martinelle, M.; Holmquist, M.; Hult, K. On the interfacial activation of Candida antarctica lipase A and B as compared with Humicola lanuginosa lipase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Lipids Lipid Metab. 1995, 1258, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arana-Peña, S.; Lokha, Y.; Fernández-Lafuente, R. Immobilization on octyl-agarose beads and some catalytic features of commercial preparations of lipase a from Candida antarctica (Novocor ADL): Comparison with immobilized lipase B from Candida antarctica. Biotechnol. Prog. 2019, 35, e2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kapoor, M.; Gupta, M. Lipase Promiscuity and its biochemical applications. Process. Biochem. 2012, 47, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, N.; dos Santos, J.C.S.; Torres, R.; Ortiz, C.; Barbosa, O.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Improved performance of lipases immobilized on heterofunctional octyl-glyoxyl agarose beads. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 11212–11222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hernandez, K.; Garcia-Verdugo, E.; Porcar, R.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Hydrolysis of triacetin catalyzed by immobilized lipases: Effect of the immobilization protocol and experimental conditions on diacetin yield. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2011, 48, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, D.B.; Albuquerque, T.L.; Rueda, N.; Virgen-Ortíz, J.J.; Tacias-Pascacio, V.G.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Evaluation of different immobilized lipases in transesterification reactions using tributyrin: Advantages of the heterofunctional octyl agarose beads. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2016, 133, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, D.B.; Albuquerque, T.L.; Rueda, N.; Sánchez-Montero, J.M.; Garcia-Verdugo, E.; Porcar, R.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Advantages of Heterofunctional Octyl Supports: Production of 1,2-Dibutyrin by Specific and Selective Hydrolysis of Tributyrin Catalyzed by Immobilized Lipases. ChemistrySelect 2016, 1, 3259–3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, K.; Garcia-Galan, C.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Simple and efficient immobilization of lipase B from Candida antarctica on porous styrene-divinylbenzene beads. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2011, 49, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villalba, M.; Verdasco-Martín, C.M.; dos Santos, J.C.S.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Otero, C. Operational stabilities of different chemical derivatives of Novozym 435 in an alcoholysis reaction. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2016, 90, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera, Z.; Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Palomo, J.M.; Guisan, J.M. Novozym 435 displays very different selectivity compared to lipase from Candida antarctica B adsorbed on other hydrophobic supports. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2009, 57, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Du, W.; Li, Q.; Sun, T.; Liu, D. Study on acyl migration kinetics of partial glycerides: Dependence on temperature and water activity. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2009, 63, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomo, J. Modulation of Enzymes Selectivity Via Immobilization. Curr. Org. Synth. 2009, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou, D.; Francis, G.W.; Aksnes, D.W.; Brekke, T.; Maartmann-Moe, K. Studies on the Oxidation of Methyl 2,3-O-Isopropylidene-beta-D-ribofuranoside with Pyridinium Dichromate. Identification of Unexpected By-Products. Acta Chem. Scand. 1990, 44, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ermolenko, L.; Sasaki, N.A.; Potier, P. An Expedient One-Step Preparation of (S)-2,3-O-Isopropylideneglyceraldehyde. Synlett 2001, 2001, 1565–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crombie, L.; Ryan, A.P.; Whiting, D.A.; Yeboah, S.O. Synthesis of 4′-O-methyl- and 4′,6-di-O-methyl-chalaurenol. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1987, 1, 2783–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, D.F.; Christos, T.E.; Hodge, C.N. Cyclohexenone Annelation by Alkylidene C−H Insertion: Synthesis of Oxo-T-cadinol. J. Org. Chem. 1996, 61, 2081–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, L.L.; Luzzio, F.A. Ultrasound in oxochromium(VI)-amine-mediated oxidations - modifications of the Corey-Suggs oxidation for the facile conversion of alcohols to carbonyl compounds. J. Org. Chem. 1989, 54, 5387–5390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wipf, P.; Jung, J.-K. Formal Total Synthesis of (+)-Diepoxin σ. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 6319–6337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deiters, A.; Mück-Lichtenfeld, C.; Fröhlich, R.; Hoppe, D. Planar-Chiral (2E,7Z)- and (2Z,7E)-Cyclonona-2,7-dien-1-yl Carbamates by Asymmetric, Bis-Allylic α,α′-Cycloalkylation—Studies on Their Conformational Stability. Chem. A Eur. J. 2002, 8, 1833–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzzio, F.A.; Fitch, R.W.; Moore, W.J.; Mudd, K.J. A Facile Oxidation of Alcohols Using Pyridinium Chlorochromate/Silica Gel. J. Chem. Educ. 1999, 76, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, K.; Dannenfelser, R.-M. In vitro hemolysis: Guidance for the pharmaceutical scientist. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006, 95, 1173–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, D.M.; Shirai, K.; Jackson, R.L.; Harmony, J.A. Lipoprotein lipase catalyzed hydrolysis of water-soluble p-nitrophenyl esters. Inhibition by apolipoprotein C-II. Biochemistry 1982, 21, 6872–6879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, D.; Ortiz, C.; Torres, R. Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of antibacterial effect of Ag nanoparticles against Escherichia coli O157:H7 and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Int. J. Nanomedicine 2014, 9, 1717–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cruz, J.; Flórez, J.; Torres, R.; Urquiza, M.; Gutiérrez, J.A.; Guzmán, F.; Ortiz, C.C. Antimicrobial activity of a new synthetic peptide loaded in polylactic acid or poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid nanoparticles against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli O157:H7 and methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Nanotechnology 2017, 28, 135102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeast. Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute. Available online: https://clsi.org/standards/products/microbiology/documents/m27/ (accessed on 24 August 2020).

- Krzyzaniak, J.F.; Nuúnñez, F.A.A.; Raymond, D.M.; Yalkowsky, S.H. Lysis of human red blood cells. 4. Comparison of in vitro and in vivo hemolysis data. J. Pharm. Sci. 1997, 86, 1215–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmerhorst, E.J.; Reijnders, I.M.; van ’t Hof, W.; Veerman, E.C.I.; Nieuw Amerongen, A.V. A critical comparison of the hemolytic and fungicidal activities of cationic antimicrobial peptides. FEBS Lett. 1999, 449, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Entry | Solvent | Triacetin (%) | 1,2-Diacetin (%) | 2-Monoacetin (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20% acetonitrile/sodium phosphate 500 mM pH 5.5 | 46.5 | 43.6 | 9.9 |

| 2 | Sodium phosphate 500 mM pH 5.5 | 5.4 | 71.0 | 23.6 |

| Entry | Reagent | Solvent/PCC Ratio | Ratio (GC) (2):(5):(3) ** |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PCC 2 equiv | 10 mL CH2Cl2/g PCC | 4:6:1 |

| 2 | PCC 2 equiv, AcONa 2 equiv | 10 mL CH2Cl2/g PCC | 14:1:3 |

| 3 | PCC 2 equiv | 20 mL CH2Cl2/g PCC | 3:8:4 |

| 4 | PCC 2 equiv, AcONa 1 equiv | 20 mL CH2Cl2/g PCC | 1:4:2 |

| 5 | PCC 2 equiv, AcONa 1 equiv, silica gel 2 g | 20 mL CH2Cl2/g PCC | 1:5:1 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Plata, E.; Ruiz, M.; Ruiz, J.; Ortiz, C.; Castillo, J.J.; Fernández-Lafuente, R. Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of the New 3-((2,3-Diacetoxypropanoyl)oxy)propane-1,2-diyl Diacetate Using Immobilized Lipase B from Candida antarctica and Pyridinium Chlorochromate as an Oxidizing Agent. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6501. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms21186501

Plata E, Ruiz M, Ruiz J, Ortiz C, Castillo JJ, Fernández-Lafuente R. Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of the New 3-((2,3-Diacetoxypropanoyl)oxy)propane-1,2-diyl Diacetate Using Immobilized Lipase B from Candida antarctica and Pyridinium Chlorochromate as an Oxidizing Agent. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(18):6501. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms21186501

Chicago/Turabian StylePlata, Esteban, Mónica Ruiz, Jennifer Ruiz, Claudia Ortiz, John J. Castillo, and Roberto Fernández-Lafuente. 2020. "Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of the New 3-((2,3-Diacetoxypropanoyl)oxy)propane-1,2-diyl Diacetate Using Immobilized Lipase B from Candida antarctica and Pyridinium Chlorochromate as an Oxidizing Agent" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 18: 6501. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms21186501