Estrogen Receptor Modulators in Viral Infections Such as SARS−CoV−2: Therapeutic Consequences

Abstract

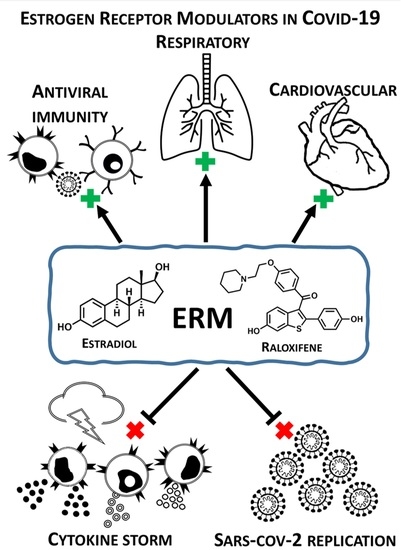

:1. Introduction

2. Physiological Estrogen Receptor-Dependent Effects and Viral Infection Susceptibility

3. Effect of Oestrogen Receptor Modulators (ERMs) on Viral Replication

4. ERMs and Estrogens as Inhibitors of SARS−CoV−2 Proteases

5. Antiviral Effect of Estrogens as a Developmental Strategy

6. Therapeutic Consequences

7. Experimental Part Describing Procedures of Molecular Docking of SARS−CoV−2 Proteases with Estrogens and ERM

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACE2 | Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 |

| ADT | AutoDockTools |

| ER | Estrogen receptor |

| ERM | Estrogen receptor modulator |

| HBV | Hepatitis B virus |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| Mpro | Main protease |

| MERS | Middle East respiratory syndrome |

| PLpro | Papain-like protease |

| SARS | Severe acute respiratory syndrome |

| SARS−CoV−2 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-α |

References

- Costeira, R.; Lee, K.A.; Murray, B.; Christiansen, C.; Castillo-Fernandez, J.; Lochlainn, M.N.; Pujol, J.C.; Macfarlane, H.; Kenny, L.C.; Buchan, I.; et al. Estrogen and COVID-19 symptoms: Associations in women from the COVID symptom study. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viveiros, A.; Rasmuson, J.; Vu, J.; Mulvagh, S.L.; Yip, C.Y.Y.; Norris, C.M.; Oudit, G.Y. Sex differences in COVID-19: Candidate pathways, genetics of ACE2, and sex hormones. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2021, 320, H296–H304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channappanavar, R.; Fett, C.; Mack, M.; ten Eyck, P.P.; Meyerholz, D.K.; Perlman, S. Sex-based differences in susceptibility to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. J. Immunol. 2017, 198, 4046–4053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-kuraishy, H.M.; Al-Gareeb, A.I.; Faidah, H.; Al-Maiahy, T.J.; Cruz-Martins, N.; Batiha, G.E.S. The looming effects of estrogen in covid-19: A rocky rollout. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 649128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, J.; Qie, G.; Yao, Q.; Sun, W.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, P.; Jiang, J.; Bai, X.; et al. Sex differences on clinical characteristics, severity, and mortality in adult patients with COVID-19: A multicentre retrospective study. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 607059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooz, M. ADAM-17: The enzyme that does it all. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010, 45, 146–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lacina, L.; Brábek, J.; Král, V.; Kodet, O.; Smetana, K. Interleukin-6: A molecule with complex biological impact in cancer. Histol. Histopathol. 2019, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giagulli, V.A.; Guastamacchia, E.; Magrone, T.; Jirillo, E.; Lisco, G.; de Pergola, G.; Triggiani, V. Worse progression of COVID-19 in men: Is testosterone a key factor? Andrology 2021, 9, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stelzig, K.E.; Canepa-Escaro, F.; Schiliro, M.; Berdnikovs, S.; Prakash, Y.S.; Chiarella, S.E. Estrogen regulates the expression of SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 in differentiated airway epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2020, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, J.; Shao, R.; Han, X.; Su, C.; Lu, W. Risk and clinical outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with rheumatic diseases compared with the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol. Int. 2021, 41, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradi, F.; Enjezab, B.; Ghadiri-Anari, A. The role of androgens in COVID-19. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 2003–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedian-Azimi, A.; Pourhoseingholi, M.A.; Saberi, M.; Behnam, B.; Sahebkar, A. Gender susceptibility to COVID-19 mortality: Androgens as the usual suspects? In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Volume 1321, pp. 261–264. [Google Scholar]

- Alopecia and Severity of COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Study in Peru—PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33664171/ (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Subramanian, A.; Anand, A.; Adderley, N.J.; Okoth, K.; Toulis, K.A.; Gokhale, K.; Sainsbury, C.; O’Reilly, M.W.; Arlt, W.; Nirantharakumar, K. Increased COVID-19 infections in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A population-based study. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2021, 184, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanana, N.; Palmo, T.; Sharma, K.; Kumar, R.; Graham, B.B.; Pasha, Q. Sex-derived attributes contributing to SARS-CoV-2 mortality. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 319, E562–E567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.L.; Flanagan, K.L. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 626–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, K.S.; Anguera, M.C. Time to get ill: The intersection of viral infections, sex, and the X chromosome. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2021, 19, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakimchuk, K.; Jondal, M.; Okret, S. Estrogen receptor α and β in the normal immune system and in lymphoid malignancies. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2013, 375, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovats, S. Estrogen receptors regulate innate immune cells and signaling pathways. Cell. Immunol. 2015, 294, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wray, S.; Arrowsmith, S. The physiological mechanisms of the sex-based difference in outcomes of COVID19 infection. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breithaupt-Faloppa, A.C.; de Jesus Correia, C.; Prado, C.M.; Stilhano, R.S.; Ureshino, R.P.; Moreira, L.F.P. 17b-Estradiol, a Potential Ally to Alleviate SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Clinics 2020, 75, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinna, G. Sex and COVID-19: A protective role for reproductive steroids. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 32, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Xu, Y.; Li, J.; Cui, X.; Tan, X.; Zhang, H.; Dang, L. Sex differences in immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Biosci. Rep. 2021, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatansev, H.; Kadiyoran, C.; Cumhur Cure, M.; Cure, E. COVID-19 infection can cause chemotherapy resistance development in patients with breast cancer and tamoxifen may cause susceptibility to COVID-19 infection. Med. Hypotheses 2020, 143, 110091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravaccini, S.; Fonzi, E.; Tebaldi, M.; Angeli, D.; Martinelli, G.; Nicolini, F.; Parrella, P.; Mazza, M. Estrogen and androgen receptor inhibitors: Unexpected allies in the fight against COVID-19. Cell Transplant. 2021, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong, D.O.; Barffour, I.K.; Boye, A.; Aninagyei, E.; Ocansey, S.; Morna, M.T. Male predisposition to severe COVID-19: Review of evidence and potential therapeutic prospects. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 131, 110748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Li, L.; Wang, X. Identifying pathways and networks associated with the SARS-CoV-2 cell receptor ACE2 based on gene expression profiles in normal and SARS-CoV-2-infected human tissues. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020, 7, 568954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadel, S.; Kovats, S. Sex hormones regulate innate immune cells and promote sex differences in respiratory virus infection. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millas, I.; Duarte Barros, M. Estrogen receptors and their roles in the immune and respiratory systems. Anat. Rec. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Jerkic, M.; Slutsky, A.S.; Zhang, H. Molecular mechanisms of sex bias differences in COVID-19 mortality. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, A.; Buskiewicz, I.; Huber, S.A. Age-associated changes in estrogen receptor ratios correlate with increased female susceptibility to coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, S.H.; Yeh, S.H.; Lin, W.H.; Yeh, K.H.; Yuan, Q.; Xia, N.S.; Chen, D.S.; Chen, P.J. Estrogen receptor α represses transcription of HBV genes via interaction with hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α. Gastroenterology 2012, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulitzky, L.; Lafer, M.M.; KuKuruga, M.A.; Silberstein, E.; Cehan, N.; Taylor, D.R. A new signaling pathway for HCV inhibition by estrogen: GPR30 activation leads to cleavage of occludin by MMP-9. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0145212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Magri, A.; Barbaglia, M.N.; Foglia, C.Z.; Boccato, E.; Burlone, M.E.; Cole, S.; Giarda, P.; Grossini, E.; Patel, A.H.; Minisini, R.; et al. 17,β-estradiol inhibits hepatitis C virus mainly by interference with the release phase of its life cycle. Liver Int. 2016, 37, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, E.; Karampatou, A.; Camm, C.; di Leo, A.; Luongo, M.; Ferrari, A.; Petta, S.; Losi, L.; Taliani, G.; Trande, P.; et al. Early menopause is associated with lack of response to antiviral therapy in women with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 2011, 140, 818–829.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lemes, R.M.R.; Costa, A.J.; Bartolomeo, C.S.; Bassani, T.B.; Nishino, M.S.; da Silva Pereira, G.J.; Smaili, S.S.; de Barros Maciel, R.M.; Braconi, C.T.; da Cruz, E.F.; et al. 17β-estradiol reduces SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro. Physiol. Rep. 2021, 9, e14707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penny, C.J.; Vassileva, K.; Jha, A.; Yuan, Y.; Chee, X.; Yates, E.; Mazzon, M.; Kilpatrick, B.S.; Muallem, S.; Marsh, M.; et al. Mining of ebola virus entry inhibitors identifies approved drugs as two-pore channel pore blockers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2019, 1866, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, S.; Ko, M.; Lee, J.; Choi, I.; Byun, S.Y.; Park, S.; Shum, D.; Kim, S. Identification of antiviral drug candidates against SARS-CoV-2 from FDA-approved drugs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemnejad-Berenji, M.; Pashapour, S.; Ghasemnejad-Berenji, H. Therapeutic potential for clomiphene, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, in the treatment of COVID-19. Med. Hypotheses 2020, 145, 110354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, E.A.; Barnes, A.B.; Wiehle, R.D.; Fontenot, G.K.; Hoenen, T.; White, J.M. Clomiphene and its isomers block ebola virus particle entry and infection with similar potency: Potential therapeutic implications. Viruses 2016, 8, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Calderone, A.; Menichetti, F.; Santini, F.; Colangelo, L.; Lucenteforte, E.; Calderone, V. Selective estrogen receptor modulators in COVID-19: A possible therapeutic option? Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, L.; Schafer, A.; Li, Y.; Cheng, H.; Medegan Fagla, B.; Shen, Z.; Nowar, R.; Dye, K.; Anantpadma, M.; Davey, R.A.; et al. Screening and reverse-engineering of estrogen receptor ligands as potent pan-filovirus inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 11085–11099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, W.R.; Cheng, F. Repurposing of FDA-approved toremifene to treat COVID-19 by blocking the spike glycoprotein and NSP14 of SARS-CoV-2. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 19, 4670–4677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Chang, J.O.; Jeong, K.; Lee, W. Raloxifene as a treatment option for viral infections. J. Microbiol. 2021, 59, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Du, X.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, H.; Lu, X.; Wu, Q.; Li, H.; Wang, H.; Shi, Y.; Gao, G.; et al. Selective inhibition of ebola entry with selective estrogen receptor modulators by disrupting the endolysosomal calcium. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohma, D.; Tajima, S.; Kato, F.; Sato, H.; Kakisaka, M.; Hishiki, T.; Kataoka, M.; Takeyama, H.; Lim, C.K.; Aida, Y.; et al. An estrogen antagonist, cyclofenil, has anti-dengue-virus activity. Arch. Virol. 2019, 164, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, E.; Stupack, D.G.; Brown, S.L.; Klemke, R.; Schlaepfer, D.D.; Nemerow, G.R. Association of P130(CAS) with phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase mediates adenovirus cell entry. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 14729–14735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Akula, S.M.; Hurley, D.J.; Wixon, R.L.; Wang, C.; Chase, C.C.L. Effect of genistein on replication of bovine herpesvirus type 1. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2002, 63, 1124–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres, A.; Donovan, S.M.; Kuhlenschmidt, M.S. Soy isoflavones and virus infections. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2009, 20, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evers, D.L.; Chao, C.F.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Huong, S.M.; Huang, E.S. Human cytomegalovirus-inhibitory flavonoids: Studies on antiviral activity and mechanism of action. Antivir. Res. 2005, 68, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stantchev, T.S.; Markovic, I.; Telford, W.G.; Clouse, K.A.; Broder, C.C. The tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein blocks HIV-1 infection in primary human macrophages. Virus Res. 2007, 123, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vela, E.M.; Bowick, G.C.; Herzog, N.K.; Aronson, J.F. Genistein treatment of cells inhibits arenavirus infection. Antivir. Res. 2008, 77, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arabyan, E.; Hakobyan, A.; Kotsinyan, A.; Karalyan, Z.; Arakelov, V.; Arakelov, G.; Nazaryan, K.; Simonyan, A.; Aroutiounian, R.; Ferreira, F.; et al. Genistein inhibits African swine fever virus replication in vitro by disrupting viral DNA synthesis. Antivir. Res. 2018, 156, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyr, N.S.; Kirb, E.N.; Anfiteatr, D.R.; Bracho, G.; Russ, A.G.; Whit, P.A.; Aloi, A.L.; Bear, M.R. Identification of estrogen receptor modulators as inhibitors of flavivirus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galindo, I.; Garaigorta, U.; Lasala, F.; Cuesta-Geijo, M.A.; Bueno, P.; Gil, C.; Delgado, R.; Gastaminza, P.; Alonso, C. Antiviral drugs targeting endosomal membrane proteins inhibit distant animal and human pathogenic viruses. Antivir. Res. 2021, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasaeifar, B.; Gomez-Gutierrez, P.; Perez, J.J. Molecular features of non-selective small molecule antagonists of the bradykinin receptors. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, B.; Zaliani, A.; Ebeling, C.; Reinshagen, J.; Bojkova, D.; Lage-Rupprecht, V.; Karki, R.; Lukassen, S.; Gadiya, Y.; Ravindra, N.G.; et al. The COVID-19 PHARMACOME: Rational selection of drug repurposing candidates from multimodal knowledge harmonization. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouznetsova, J.; Sun, W.; Martínez-Romero, C.; Tawa, G.; Shinn, P.; Chen, C.Z.; Schimmer, A.; Sanderson, P.; McKew, J.C.; Zheng, W.; et al. Identification of 53 compounds that block ebola virus-like particle entry via a repurposing screen of approved drugs. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2014, 3, e84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Wang, C.; Chang, D.; Wang, Y.; Dong, X.; Jiao, T.; Zhao, Z.; Ren, L.; dela Cruz, C.S.; Sharma, L.; et al. Identification of potent and safe antiviral therapeutic candidates against SARS-CoV-2. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 586572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.S.; Jang, Y.; Hoenen, T.; Shin, H.; Lee, Y.; Kim, M. Antiviral activity of sertindole, raloxifene and ibutamoren against transcription and replication-competent ebola virus-like particles. BMB Rep. 2020, 53, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dyall, J.; Coleman, C.M.; Hart, B.J.; Venkataraman, T.; Holbrook, M.R.; Kindrachuk, J.; Johnson, R.F.; Olinger, G.G.; Jahrling, P.B.; Laidlaw, M.; et al. Repurposing of clinically developed drugs for treatment of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 4885–4893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cham, L.B.; Friedrich, S.K.; Adomati, T.; Bhat, H.; Schiller, M.; Bergerhausen, M.; Hamdan, T.; Li, F.; Machlah, Y.M.; Ali, M.; et al. Tamoxifen protects from vesicular stomatitis virus infection. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gaisina, I.N.; Peet, N.P.; Wong, L.; Schafer, A.M.; Cheng, H.; Anantpadma, M.; Davey, R.A.; Thatcher, G.R.J.; Rong, L. Discovery and structural optimization of 4-(aminomethyl)benzamides as potent entry inhibitors of ebola and marburg virus infections. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 7211–7225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMullan, L.K.; Flint, M.; Chakrabarti, A.; Guerrero, L.; Lo, M.K.; Porter, D.; Nichol, S.T.; Spiropoulou, C.F.; Albariño, C. Characterisation of infectious ebola virus from the ongoing outbreak to guide response activities in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: A phylogenetic and in vitro analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 1023–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, Y.; Hou, Y.; Shen, J.; Huang, Y.; Martin, W.; Cheng, F. Network-based drug repurposing for novel coronavirus 2019-NCoV/SARS-CoV-2. Cell Discov. 2020, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lubrano, V.; Balzan, S. Cardiovascular risk in COVID-19 infection. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 10, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Johansen, L.M.; DeWald, L.E.; Shoemaker, C.J.; Hoffstrom, B.G.; Lear-Rooney, C.M.; Stossel, A.; Nelson, E.; Delos, S.E.; Simmons, J.A.; Grenier, J.M.; et al. A screen of approved drugs and molecular probes identifies therapeutics with anti-ebola virus activity. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aguilar-Pineda, J.A.; Albaghdadi, M.; Jiang, W.; Vera Lopez, K.J.; Davila, G.; Pharmd, D.-C.; Gómez Valdez, B.; Lindsay, M.E.; Malhotra, R.; Cardenas, C.L.L. Structural and functional analysis of female sex hormones against SARS-Cov2 cell entry. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Sun, X.; VonCannon, J.L.; Kon, N.D.; Ferrario, C.M.; Groban, L. Estrogen receptors are linked to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17 (ADAM-17), and transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) expression in the human atrium: Insights into COVID-19. Hypertens. Res. 2021, Feb 3, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, R.; Teimoori, A.; Sadeghi, A.; Mohamadkhani, A.; Rezasoltani, S.; Asadi, E.; Jouyban, A.; Sumner, S.C.J. Existing antiviral options against SARS-CoV-2 replication in COVID-19 patients. Future Microbiol. 2020, 15, 1747–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengist, H.M.; Mekonnen, D.; Mohammed, A.; Shi, R.; Jin, T. Potency, safety, and pharmacokinetic profiles of potential inhibitors targeting SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11, 2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajarshi, K.; Khan, R.; Singh, M.K.; Ranjan, T.; Ray, S.; Ray, S. Essential functional molecules associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection: Potential therapeutic targets for COVID-19. Gene 2021, 768, 145313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayeem, S.M.; Sohail, E.M.; Sudhir, G.P.; Reddy, M.S. Computational and theoretical exploration for clinical suitability of remdesivir drug to SARS-CoV-2. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrak, S.A.; Merzouk, H.; Mokhtari-Soulimane, N. Potential bioactive glycosylated flavonoids as SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors: A molecular docking and simulation studies. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, R.; Perera, L.; Tillekeratne, L.M.V. Potential SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors. Drug Discov. Today 2021, 26, 804–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouffouk, C.; Mouffouk, S.; Mouffouk, S.; Hambaba, L.; Haba, H. Flavonols as potential antiviral drugs targeting SARS-CoV-2 proteases (3CLpro and PLpro), spike protein, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) and angiotensin-converting enzyme II receptor (ACE2). Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiou, W.C.; Hsu, M.S.; Chen, Y.T.; Yang, J.M.; Tsay, Y.G.; Huang, H.C.; Huang, C. Repurposing existing drugs: Identification of SARS-CoV-2 3C-like protease inhibitors. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2021, 36, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Giefing-Kröll, C.; Berger, P.; Lepperdinger, G.; Grubeck-Loebenstein, B. How sex and age affect immune responses, susceptibility to infections, and response to vaccination. Aging Cell 2015, 14, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schock, H.; Zeleniuch-Jacquotte, A.; Lundin, E.; Grankvist, K.; Lakso, H.Å.; Idahl, A.; Lehtinen, M.; Surcel, H.M.; Fortner, R.T. Hormone concentrations throughout uncomplicated pregnancies: A longitudinal study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, T.A.; Engel, S.M.; Sperling, R.S.; Kellerman, L.; Lo, Y.; Wallenstein, S.; Escribese, M.M.; Garrido, J.L.; Singh, T.; Loubeau, M.; et al. Characterizing the pregnancy immune phenotype: Results of the viral immunity and pregnancy (VIP) study. J. Clin. Immunol. 2012, 32, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, G.; Rahimi, B.; Panahi, M.; Abkhiz, S.; Saraygord-Afshari, N.; Milani, M.; Alizadeh, E. An overview of betacoronaviruses-associated severe respiratory syndromes, focusing on sex-type-specific immune responses. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 92, 107365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, R.L.; Ohashi, T.; Gordon, J.; Nathan Mowa, C. A proteomic profile of postpartum cervical repair in mice. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2018, 60, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, H.J.; Oh, J.W.; Spandau, D.F.; Tholpady, S.; Diaz, J.; Schroeder, L.J.; Offutt, C.D.; Glick, A.B.; Plikus, M.V.; Koyama, S.; et al. Estrogen modulates mesenchyme-epidermis interactions in the adult nipple. Development 2017, 144, 1498–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yang, F.; Li, N.; Gaman, M.A.; Wang, N. Raloxifene has favorable effects on the lipid profile in women explaining its beneficial effect on cardiovascular risk: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 166, 105512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunders, M.J.; Altfeld, M. Implications of sex differences in immunity for SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis and design of therapeutic interventions. Immunity 2020, 53, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussman, J.P. Cellular and molecular pathways of COVID-19 and potential points of therapeutic intervention. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- More, S.A.; Patil, A.S.; Sakle, N.S.; Mokale, S.N. Network analysis and molecular mapping for SARS-CoV-2 to reveal drug targets and repurposing of clinically developed drugs. Virology 2021, 555, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Shankar, R.; Ko, M.; Chang, C.D.; Yeh, S.-J.; Li, S.; Liu, K.; Zhou, G.; Xing, J.; VanVelsen, A.; et al. Sex differences in viral entry protein expression, host responses to SARS-CoV-2, and in vitro responses to sex steroid hormone treatment in COVID-19. Res. Sq. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Human Protein Atlas. Available online: https://www.proteinatlas.org/ (accessed on 14 April 2021).

- Cadegiani, F.A.; McCoy, J.; Gustavo Wambier, C.; Goren, A. Early antiandrogen therapy with dutasteride reduces viral shedding, inflammatory responses, and time-to-remission in males with COVID-19: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled interventional trial (EAT-DUTA AndroCoV Trial—Biochemical). Cureus 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; ur Rasool, R.; Russell, R.M.; Natesan, R.; Asangani, I.A. Targeting androgen regulation of TMPRSS2 and ACE2 as a therapeutic strategy to combat COVID-19. iScience 2021, 24, 102254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotfis, K.; Lechowicz, K.; Drożdżal, S.; Niedźwiedzka-Rystwej, P.; Wojdacz, T.K.; Grywalska, E.; Biernawska, J.; Wiśniewska, M.; Parczewski, M. COVID-19—The potential beneficial therapeutic effects of spironolactone during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gennari, L.; Merlotti, D.; de Paola, V.; Martini, G.; Nuti, R. Bazedoxifene for the prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2008, 4, 1229–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fujiwara, S.; Hamaya, E.; Sato, M.; Graham-Clarke, P.; Flynn, J.A.; Burge, R. Systematic review of raloxifene in postmenopausal Japanese women with osteoporosis or low bone mass (osteopenia). Clin. Interv. Aging 2014, 9, 1879–1893. [Google Scholar]

- Thilakasiri, P.; Huynh, J.; Poh, A.R.; Tan, C.W.; Nero, T.L.; Tran, K.; Parslow, A.C.; Afshar-Sterle, S.; Baloyan, D.; Hannan, N.J.; et al. Repurposing the selective estrogen receptor modulator bazedoxifene to suppress gastrointestinal cancer growth. EMBO Mol. Med. 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozios, I.; Seel, N.N.; Hering, N.A.; Hartmann, L.; Liu, V.; Camaj, P.; Müller, M.H.; Lee, L.D.; Bruns, C.J.; Kreis, M.E.; et al. Raloxifene inhibits pancreatic adenocarcinoma growth by interfering with ERβ and IL-6/Gp130/STAT3 signaling. Cell. Oncol. 2021, 44, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brábek, J.; Jakubek, M.; Vellieux, F.; Novotný, J.; Kolář, M.; Lacina, L.; Szabo, P.; Strnadová, K.; Rösel, D.; Dvořánková, B.; et al. Interleukin-6: Molecule in the intersection of cancer, ageing and COVID-19. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smetana, K.; Smetana, K.; Brábek, J. Role of Interleukin-6 in Lung Complications in Patients with COVID-19: Therapeutic Implications. In Vivo 2020, 34, 1589–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smetana, K.; Rosel, D.; Brábek, J. Raloxifene and bazedoxifene could be promising candidates for preventing the COVID-19 related cytokine storm, ARDS and mortality. In Vivo 2020, 34, 3027–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borku Uysal, B.; Ikitimur, H.; Yavuzer, S.; Ikitimur, B.; Uysal, H.; Islamoglu, M.S.; Ozcan, E.; Aktepe, E.; Yavuzer, H.; Cengiz, M. Tocilizumab challenge: A series of cytokine storm therapy experiences in hospitalized COVID-19 pneumonia patients. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 2648–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salama, C.; Han, J.; Yau, L.; Reiss, W.G.; Kramer, B.; Neidhart, J.D.; Criner, G.J.; Kaplan-Lewis, E.; Baden, R.; Pandit, L.; et al. Tocilizumab in patients hospitalized with covid-19 pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Eynde, E.; Gasch, O.; Oliva, J.C.; Prieto, E.; Calzado, S.; Gomila, A.; Machado, M.L.; Falgueras, L.; Ortonobes, S.; Morón, A.; et al. Corticosteroids and tocilizumab reduce in-hospital mortality in severe COVID-19 pneumonia: A retrospective study in a Spanish hospital. Infect. Dis. 2021, 53, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Substance (Relation to Estrogen) | Virus | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Estradiol | SARS−CoV−2 | Blocking of virus entry [36] |

| Bazedoxifene (agonist/antagonist) | EBOLA SARS−CoV−2 | Blocking of endolysosomal system [37] Interaction with SARS−CoV−2 main protease [38] |

| Clomiphene (analogue) | SARS−CoV−2 EBOLA | Blocking of endolysosomal system [39] Blocking of virus entry [37,40,41,42,43,44,45] |

| Cyclofenil (agonist/antagonist) | Dengue, Zika | RNA synthesis inhibition [46] |

| Genestin (analogue) | Adenoviruses Bovine herpesvirus 1 Virus herpes simplex 1/2 Human herpesvirus 8 Moloney murine leukemia Rotaviruses Simian virus 40 Human cytomegalovirus Human immunodeficiency 1 | Blocking of virus entry [47] Reduction in virus replication [48] Blocking of virus entry and translation [49] Reduction in virus DNA synthesis [50] Blocking of virus entry [51] |

| Genistein (analogue) | Arenaviruses Bovine viral diarrhoea African swine fever virus | Inhibition of tyrosinkinase [52] Blocking of virus entry and translation [49] Disruption of DNA synthesis [53] |

| Quercetin (analogue) | Adenoviruses | Blocking of virus entry and translation [49] |

| Quinestrol (analogue) | Flaviviruses (ZIKA, Dengue, West Nile) | Reduction in virus RNA synthesis [54] |

| Raloxifene (agonist/antagonist) | Flaviviruses (ZIKA, Dengue, West Nile) EBOLA, SARS−CoV−2 | Reduction in virus RNA synthesis [54,55] Blocking of virus entry [44,56,57,58,59,60] |

| Ridaifene-b(+XL-147) (Tamoxifen analogue without effect on ER) | EBOLA | Blocking of virus entry [42] |

| Tamoxifen (agonist/antagonist) | MERS Vesicular stomatitis virus EBOLA | Inhibition of virus replication [61] Inhibition of virus replication and activation of macrophages [62] Blocking of virus entry [45,58] |

| Toremifene (agonist/antagonist) | MERS EBOLA SARS−CoV−2 | Inhibition of virus replication [61] Blocking of virus entry [43,58,63,64] Blocking of virus entry [65,66] |

| Agents | Main Protease | Papain-Like Protease (Monomer) | Papain-Like Protease (Trimer) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estradiol | −7.14 | −6.86 | −7.32 |

| Estrane | −7.59 | −6.28 | −7.51 |

| Estriol | −7.9 | −6.43 | −7.82 |

| Estrone | −8.96 | −6.94 | −7.61 |

| Bazedoxifene | −10.13 | −5.54 | −7.69 |

| Genistine | −7.7 | −6.07 | −6.25 |

| Raloxifene | −8.61 | −6.14 | −7.49 |

| Function | Potential Effect of ERM | Dependence on ERM Binding to ER | Potential Clinical/Therapeutic Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary function | Stimulated | Yes [21,29] | Yes |

| ACE2 expression in airways | Reduced | Yes [9] | Yes |

| Cardiovascular function | Stimulated | Yes [21] | Yes |

| Vascular endothelium injury | Reduced | No [21] | Yes |

| Increased vascular permeability | Reduced | Yes/No [21] | Yes |

| Immune response against SARS−CoV−2 | Stimulated | Yes [16] | Yes |

| Sensitivity to vaccination | Stimulated | Yes [16] | Yes |

| Hypersecretion of cytokines including IL-6 | Reduced | Yes [16,68] | Yes |

| IL-6 binding to receptor | Reduced | No [96,99] | Yes |

| Virus replication (virus entry) | Reduced | Yes/No (see Table 1) | Yes |

| Virus replication (release of RNA from endosome) | Reduced | No (see Table 1) | Yes |

| Virus replication (inhibition of proteases) | Reduced | No (see Table 1, [77]) | Yes |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abramenko, N.; Vellieux, F.; Tesařová, P.; Kejík, Z.; Kaplánek, R.; Lacina, L.; Dvořánková, B.; Rösel, D.; Brábek, J.; Tesař, A.; et al. Estrogen Receptor Modulators in Viral Infections Such as SARS−CoV−2: Therapeutic Consequences. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6551. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms22126551

Abramenko N, Vellieux F, Tesařová P, Kejík Z, Kaplánek R, Lacina L, Dvořánková B, Rösel D, Brábek J, Tesař A, et al. Estrogen Receptor Modulators in Viral Infections Such as SARS−CoV−2: Therapeutic Consequences. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(12):6551. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms22126551

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbramenko, Nikita, Fréderic Vellieux, Petra Tesařová, Zdeněk Kejík, Robert Kaplánek, Lukáš Lacina, Barbora Dvořánková, Daniel Rösel, Jan Brábek, Adam Tesař, and et al. 2021. "Estrogen Receptor Modulators in Viral Infections Such as SARS−CoV−2: Therapeutic Consequences" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 12: 6551. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms22126551